User login

The terms “hospital medicine” and “evidence-based medicine” (EBM) are both recent arrivals in the history of medicine. Both have spread through medicine at a rapid pace, highlighting the attraction and fundamental soundness of their core ideas. Much has been written about the benefits of the hospitalist movement regarding quality, patient throughput and financial indicators. The next phase in the revolution of patient care is the confluence of technology, EBM, and hospital medicine. One of the pillars for the continued success of the hospital medicine movement will be EBM. EBM must become an integral part of the skill set for all hospitalists.

EBM is an analytical approach with a fundamental knowledge base and a set of tools. The exponential growth of clinical information requires that physicians use an analytical approach for answering clinical questions and keeping up-to-date. This may be easier if you work at an academic center rather than a non-teaching hospital, although this is not guaranteed. Regardless of the working environment, an analytical approach will be needed if we are to build on initial success and unrealized potential to improve quality and patient safety.

The term “EBM” was introduced by a group of clinician researchers and educators at McMaster University during the early 1990s. It was initially defined as “a systemic approach to analyzed published research as the basis of clinical decision making.” Subsequently, as the EBM movement matured as a discipline, the early proponents and developers provided a more complete definition: “Evidence based medicine is the conscientious, explicit, and judicious use of current best evidence in making decisions about the care of individual patients. The practice of evidence-based medicine means integrating individual clinical expertise with the best available external clinical evidence from systematic research (1).”

Of course, the concept of practicing medicine based on the scientific method has been around for years. The days of bloodletting with leeches are behind us, but rigorous scientific evaluation of medicine reached critical mass only in the last century. The first double-blind randomized controlled trial (RCT) was conducted in 1931; the study tested the use of sanocrysin for treatment of tuberculosis (2). Since then, there has been an exponential growth in clinical trials. This information explosion requires new approaches to integrating the ever-increasing knowledge with patient care; the concurrent revolution in information technology provides opportunities limited only by our own imaginations.

EBM is not without its critics: “It is cookbook medicine,” “It focuses on cost efficiency,” “I can’t find an RCT that fits my patient,” and “It doesn’t take into account the clinician’s experience” are often argued points. If EBM is not used effectively, all the criticisms are appropriate. Sacket, one of the earliest proponents and likely EBM’s most eloquent champion, refuted the claim that EBM is “cookbook medicine.” He argued that EBM requires a bottom-up approach that integrates the best external evidence with individual clinical expertise and patients’ choice. External clinical evidence informs, but does not replace, individual clinical expertise. The physician must decide whether the external evidence applies to the individual patient at all and, if so, how it should be integrated into a clinical decision (1).

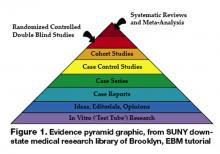

Neither is EBM strictly about RCTs and meta-analysis. It’s about tracking down the best available evidence for your question and, thus, your patient. Sometimes a cohort study is best when you want to find the prognosis of a certain illness. Similarly, a cross-sectional study may be most appropriate when you’re trying to determine the sensitivity and specificity of a test. If a disease once thought universally fatal is proven otherwise in a case report, then a randomized control trial is hardly necessary. Finally, an RCT or meta-analysis is not always going to be available for the disease process you are dealing with, but EBM gives us the skill set to look down the evidence pyramid and find the next best thing (Figure 1).

It is also clear that EBM is not about cost cutting, although many hospital medicine programs were started with this as the primary goal, given the current healthcare environment. Certainly fears exist that EBM is being used by healthcare managers, organizations, and administrators as a cost-efficiency tool. It may be that good evidence is cost-efficient in certain situations, while in others it may require the healthcare system to invest more in itself if available evidence supports doing so. Thus it is imperative that hospitalists accept the challenge of incorporating EBM into their daily practice and become leaders in its application, with patient safety and quality of care as primary goals. If we don’t, others will define the role of EBM for us, with a potential for poor outcomes for the patient and the profession.

The EBM skill set and its tools are being continuously refined, with the evidence pyramid as one of the most basic principles (3). This evidence pyramid is a model for grading the evidence. It puts in perspective the different grades of evidence or study designs. For example, a systematic review of randomized controlled trials that show consistent results provides the highest quality evidence and is ranked accordingly in the pyramid. In contrast, a case report or case series of a treatment would be ranked much lower.

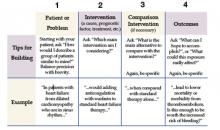

The first step in incorporating EBM into one’s daily practice requires an understanding of its analytical approach and access to the necessary tools. The process begins with asking a question that is answerable. A well-built clinical question is one that benefits the patient and clinician. Such questions are directly relevant to patient problems and phrased in ways that direct your search to relevant and precise answers.

In forming the question the following process, referred to as the PICO method, is helpful (4).

With the question formed, consider what type of question you have. This is often referred to as the typology of the question.

- Clinical Findings: Gathering and interpreting findings from the history, clinical examination, and test results.

- Etiology: Identifying causes for disease.

- Differential Diagnosis: Ranking by likelihood, seriousness, and treatability of the patients problem.

- Prognosis: Figuring out how to estimate the likely clinical course and complications over time of the disease

- Therapy: Selecting treatments to offer that do more good than harm and that are worth the effort and cost of using them.

- Prevention: Reducing the chance of disease by identifying and modifying risk factors and how to diagnose disease early by screening.

- Self-improvement: Keeping up-to-date, improve your clinical skills, and run a better, more efficient clinical practice.

The types of questions can next be matched to the type of research that may provide the answer:

- Diagnosis: prospective cohort study with good quality validation against “gold standard.”

- Prognosis: prospective cohort study.

- Therapy or prevention: prospective, randomized controlled clinical trial (RCT).

- Harm/Etiology: RCT, cohort or case-control study (probably retrospective).

- Economic: analysis of sensible costs against evidence-based outcome.

Once the question has been formed, the following steps lie ahead: finding the evidence, critically appraising the evidence, acting on the evidence, and, finally, evaluating one’s performance. Very much like the formation of the question, each of the subsequent steps involves an analytical approach that can be mastered. Technology—particularly personal computers, the Internet and PDAs—has made the task of mastering EBM easier in many ways. The additional steps in using EBM effectively will be addressed in future articles. A list of useful links is provided below.

http://library.downstate.edu/EBM2/contents.htm

http://healthsystem.virginia.edu/internet/library/collections/ebm/index.cfm

Dr. Kathuria may be reached at Navneet.kathuria@mssm.edu.

Endnotes

- Guyatt GH, Haynes RB, Jaeschke RZ, et al. Users’ guides to the medical literature: XXV. Evidence-based medicine: principles for applying the users’ guides to patient care. Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group. JAMA. 2000;284:1290-6.

- Claridge, J, Fabian, T. History and Development of Evidence Based Medicine. World Journal of Surgery 2005

- Guyatt GH, Haynes RB, et. al. Users’ guides to the medical literature: XXV. Evidence-Based Medicine: Principles for Applying the Users’ Guides to Patient Care. 2000;284:1290-1296

- Sackett DL, Richardson WS, Rosenberg W, Haynes RB (1997). Evidence-based medicine: How to practice and teach EBM. New York: Churchill Livingston

The terms “hospital medicine” and “evidence-based medicine” (EBM) are both recent arrivals in the history of medicine. Both have spread through medicine at a rapid pace, highlighting the attraction and fundamental soundness of their core ideas. Much has been written about the benefits of the hospitalist movement regarding quality, patient throughput and financial indicators. The next phase in the revolution of patient care is the confluence of technology, EBM, and hospital medicine. One of the pillars for the continued success of the hospital medicine movement will be EBM. EBM must become an integral part of the skill set for all hospitalists.

EBM is an analytical approach with a fundamental knowledge base and a set of tools. The exponential growth of clinical information requires that physicians use an analytical approach for answering clinical questions and keeping up-to-date. This may be easier if you work at an academic center rather than a non-teaching hospital, although this is not guaranteed. Regardless of the working environment, an analytical approach will be needed if we are to build on initial success and unrealized potential to improve quality and patient safety.

The term “EBM” was introduced by a group of clinician researchers and educators at McMaster University during the early 1990s. It was initially defined as “a systemic approach to analyzed published research as the basis of clinical decision making.” Subsequently, as the EBM movement matured as a discipline, the early proponents and developers provided a more complete definition: “Evidence based medicine is the conscientious, explicit, and judicious use of current best evidence in making decisions about the care of individual patients. The practice of evidence-based medicine means integrating individual clinical expertise with the best available external clinical evidence from systematic research (1).”

Of course, the concept of practicing medicine based on the scientific method has been around for years. The days of bloodletting with leeches are behind us, but rigorous scientific evaluation of medicine reached critical mass only in the last century. The first double-blind randomized controlled trial (RCT) was conducted in 1931; the study tested the use of sanocrysin for treatment of tuberculosis (2). Since then, there has been an exponential growth in clinical trials. This information explosion requires new approaches to integrating the ever-increasing knowledge with patient care; the concurrent revolution in information technology provides opportunities limited only by our own imaginations.

EBM is not without its critics: “It is cookbook medicine,” “It focuses on cost efficiency,” “I can’t find an RCT that fits my patient,” and “It doesn’t take into account the clinician’s experience” are often argued points. If EBM is not used effectively, all the criticisms are appropriate. Sacket, one of the earliest proponents and likely EBM’s most eloquent champion, refuted the claim that EBM is “cookbook medicine.” He argued that EBM requires a bottom-up approach that integrates the best external evidence with individual clinical expertise and patients’ choice. External clinical evidence informs, but does not replace, individual clinical expertise. The physician must decide whether the external evidence applies to the individual patient at all and, if so, how it should be integrated into a clinical decision (1).

Neither is EBM strictly about RCTs and meta-analysis. It’s about tracking down the best available evidence for your question and, thus, your patient. Sometimes a cohort study is best when you want to find the prognosis of a certain illness. Similarly, a cross-sectional study may be most appropriate when you’re trying to determine the sensitivity and specificity of a test. If a disease once thought universally fatal is proven otherwise in a case report, then a randomized control trial is hardly necessary. Finally, an RCT or meta-analysis is not always going to be available for the disease process you are dealing with, but EBM gives us the skill set to look down the evidence pyramid and find the next best thing (Figure 1).

It is also clear that EBM is not about cost cutting, although many hospital medicine programs were started with this as the primary goal, given the current healthcare environment. Certainly fears exist that EBM is being used by healthcare managers, organizations, and administrators as a cost-efficiency tool. It may be that good evidence is cost-efficient in certain situations, while in others it may require the healthcare system to invest more in itself if available evidence supports doing so. Thus it is imperative that hospitalists accept the challenge of incorporating EBM into their daily practice and become leaders in its application, with patient safety and quality of care as primary goals. If we don’t, others will define the role of EBM for us, with a potential for poor outcomes for the patient and the profession.

The EBM skill set and its tools are being continuously refined, with the evidence pyramid as one of the most basic principles (3). This evidence pyramid is a model for grading the evidence. It puts in perspective the different grades of evidence or study designs. For example, a systematic review of randomized controlled trials that show consistent results provides the highest quality evidence and is ranked accordingly in the pyramid. In contrast, a case report or case series of a treatment would be ranked much lower.

The first step in incorporating EBM into one’s daily practice requires an understanding of its analytical approach and access to the necessary tools. The process begins with asking a question that is answerable. A well-built clinical question is one that benefits the patient and clinician. Such questions are directly relevant to patient problems and phrased in ways that direct your search to relevant and precise answers.

In forming the question the following process, referred to as the PICO method, is helpful (4).

With the question formed, consider what type of question you have. This is often referred to as the typology of the question.

- Clinical Findings: Gathering and interpreting findings from the history, clinical examination, and test results.

- Etiology: Identifying causes for disease.

- Differential Diagnosis: Ranking by likelihood, seriousness, and treatability of the patients problem.

- Prognosis: Figuring out how to estimate the likely clinical course and complications over time of the disease

- Therapy: Selecting treatments to offer that do more good than harm and that are worth the effort and cost of using them.

- Prevention: Reducing the chance of disease by identifying and modifying risk factors and how to diagnose disease early by screening.

- Self-improvement: Keeping up-to-date, improve your clinical skills, and run a better, more efficient clinical practice.

The types of questions can next be matched to the type of research that may provide the answer:

- Diagnosis: prospective cohort study with good quality validation against “gold standard.”

- Prognosis: prospective cohort study.

- Therapy or prevention: prospective, randomized controlled clinical trial (RCT).

- Harm/Etiology: RCT, cohort or case-control study (probably retrospective).

- Economic: analysis of sensible costs against evidence-based outcome.

Once the question has been formed, the following steps lie ahead: finding the evidence, critically appraising the evidence, acting on the evidence, and, finally, evaluating one’s performance. Very much like the formation of the question, each of the subsequent steps involves an analytical approach that can be mastered. Technology—particularly personal computers, the Internet and PDAs—has made the task of mastering EBM easier in many ways. The additional steps in using EBM effectively will be addressed in future articles. A list of useful links is provided below.

http://library.downstate.edu/EBM2/contents.htm

http://healthsystem.virginia.edu/internet/library/collections/ebm/index.cfm

Dr. Kathuria may be reached at Navneet.kathuria@mssm.edu.

Endnotes

- Guyatt GH, Haynes RB, Jaeschke RZ, et al. Users’ guides to the medical literature: XXV. Evidence-based medicine: principles for applying the users’ guides to patient care. Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group. JAMA. 2000;284:1290-6.

- Claridge, J, Fabian, T. History and Development of Evidence Based Medicine. World Journal of Surgery 2005

- Guyatt GH, Haynes RB, et. al. Users’ guides to the medical literature: XXV. Evidence-Based Medicine: Principles for Applying the Users’ Guides to Patient Care. 2000;284:1290-1296

- Sackett DL, Richardson WS, Rosenberg W, Haynes RB (1997). Evidence-based medicine: How to practice and teach EBM. New York: Churchill Livingston

The terms “hospital medicine” and “evidence-based medicine” (EBM) are both recent arrivals in the history of medicine. Both have spread through medicine at a rapid pace, highlighting the attraction and fundamental soundness of their core ideas. Much has been written about the benefits of the hospitalist movement regarding quality, patient throughput and financial indicators. The next phase in the revolution of patient care is the confluence of technology, EBM, and hospital medicine. One of the pillars for the continued success of the hospital medicine movement will be EBM. EBM must become an integral part of the skill set for all hospitalists.

EBM is an analytical approach with a fundamental knowledge base and a set of tools. The exponential growth of clinical information requires that physicians use an analytical approach for answering clinical questions and keeping up-to-date. This may be easier if you work at an academic center rather than a non-teaching hospital, although this is not guaranteed. Regardless of the working environment, an analytical approach will be needed if we are to build on initial success and unrealized potential to improve quality and patient safety.

The term “EBM” was introduced by a group of clinician researchers and educators at McMaster University during the early 1990s. It was initially defined as “a systemic approach to analyzed published research as the basis of clinical decision making.” Subsequently, as the EBM movement matured as a discipline, the early proponents and developers provided a more complete definition: “Evidence based medicine is the conscientious, explicit, and judicious use of current best evidence in making decisions about the care of individual patients. The practice of evidence-based medicine means integrating individual clinical expertise with the best available external clinical evidence from systematic research (1).”

Of course, the concept of practicing medicine based on the scientific method has been around for years. The days of bloodletting with leeches are behind us, but rigorous scientific evaluation of medicine reached critical mass only in the last century. The first double-blind randomized controlled trial (RCT) was conducted in 1931; the study tested the use of sanocrysin for treatment of tuberculosis (2). Since then, there has been an exponential growth in clinical trials. This information explosion requires new approaches to integrating the ever-increasing knowledge with patient care; the concurrent revolution in information technology provides opportunities limited only by our own imaginations.

EBM is not without its critics: “It is cookbook medicine,” “It focuses on cost efficiency,” “I can’t find an RCT that fits my patient,” and “It doesn’t take into account the clinician’s experience” are often argued points. If EBM is not used effectively, all the criticisms are appropriate. Sacket, one of the earliest proponents and likely EBM’s most eloquent champion, refuted the claim that EBM is “cookbook medicine.” He argued that EBM requires a bottom-up approach that integrates the best external evidence with individual clinical expertise and patients’ choice. External clinical evidence informs, but does not replace, individual clinical expertise. The physician must decide whether the external evidence applies to the individual patient at all and, if so, how it should be integrated into a clinical decision (1).

Neither is EBM strictly about RCTs and meta-analysis. It’s about tracking down the best available evidence for your question and, thus, your patient. Sometimes a cohort study is best when you want to find the prognosis of a certain illness. Similarly, a cross-sectional study may be most appropriate when you’re trying to determine the sensitivity and specificity of a test. If a disease once thought universally fatal is proven otherwise in a case report, then a randomized control trial is hardly necessary. Finally, an RCT or meta-analysis is not always going to be available for the disease process you are dealing with, but EBM gives us the skill set to look down the evidence pyramid and find the next best thing (Figure 1).

It is also clear that EBM is not about cost cutting, although many hospital medicine programs were started with this as the primary goal, given the current healthcare environment. Certainly fears exist that EBM is being used by healthcare managers, organizations, and administrators as a cost-efficiency tool. It may be that good evidence is cost-efficient in certain situations, while in others it may require the healthcare system to invest more in itself if available evidence supports doing so. Thus it is imperative that hospitalists accept the challenge of incorporating EBM into their daily practice and become leaders in its application, with patient safety and quality of care as primary goals. If we don’t, others will define the role of EBM for us, with a potential for poor outcomes for the patient and the profession.

The EBM skill set and its tools are being continuously refined, with the evidence pyramid as one of the most basic principles (3). This evidence pyramid is a model for grading the evidence. It puts in perspective the different grades of evidence or study designs. For example, a systematic review of randomized controlled trials that show consistent results provides the highest quality evidence and is ranked accordingly in the pyramid. In contrast, a case report or case series of a treatment would be ranked much lower.

The first step in incorporating EBM into one’s daily practice requires an understanding of its analytical approach and access to the necessary tools. The process begins with asking a question that is answerable. A well-built clinical question is one that benefits the patient and clinician. Such questions are directly relevant to patient problems and phrased in ways that direct your search to relevant and precise answers.

In forming the question the following process, referred to as the PICO method, is helpful (4).

With the question formed, consider what type of question you have. This is often referred to as the typology of the question.

- Clinical Findings: Gathering and interpreting findings from the history, clinical examination, and test results.

- Etiology: Identifying causes for disease.

- Differential Diagnosis: Ranking by likelihood, seriousness, and treatability of the patients problem.

- Prognosis: Figuring out how to estimate the likely clinical course and complications over time of the disease

- Therapy: Selecting treatments to offer that do more good than harm and that are worth the effort and cost of using them.

- Prevention: Reducing the chance of disease by identifying and modifying risk factors and how to diagnose disease early by screening.

- Self-improvement: Keeping up-to-date, improve your clinical skills, and run a better, more efficient clinical practice.

The types of questions can next be matched to the type of research that may provide the answer:

- Diagnosis: prospective cohort study with good quality validation against “gold standard.”

- Prognosis: prospective cohort study.

- Therapy or prevention: prospective, randomized controlled clinical trial (RCT).

- Harm/Etiology: RCT, cohort or case-control study (probably retrospective).

- Economic: analysis of sensible costs against evidence-based outcome.

Once the question has been formed, the following steps lie ahead: finding the evidence, critically appraising the evidence, acting on the evidence, and, finally, evaluating one’s performance. Very much like the formation of the question, each of the subsequent steps involves an analytical approach that can be mastered. Technology—particularly personal computers, the Internet and PDAs—has made the task of mastering EBM easier in many ways. The additional steps in using EBM effectively will be addressed in future articles. A list of useful links is provided below.

http://library.downstate.edu/EBM2/contents.htm

http://healthsystem.virginia.edu/internet/library/collections/ebm/index.cfm

Dr. Kathuria may be reached at Navneet.kathuria@mssm.edu.

Endnotes

- Guyatt GH, Haynes RB, Jaeschke RZ, et al. Users’ guides to the medical literature: XXV. Evidence-based medicine: principles for applying the users’ guides to patient care. Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group. JAMA. 2000;284:1290-6.

- Claridge, J, Fabian, T. History and Development of Evidence Based Medicine. World Journal of Surgery 2005

- Guyatt GH, Haynes RB, et. al. Users’ guides to the medical literature: XXV. Evidence-Based Medicine: Principles for Applying the Users’ Guides to Patient Care. 2000;284:1290-1296

- Sackett DL, Richardson WS, Rosenberg W, Haynes RB (1997). Evidence-based medicine: How to practice and teach EBM. New York: Churchill Livingston