User login

An 86-year-old woman with hypertension, osteoporosis, and mild cognitive impairment presents with episodes of palpitations and heart “fluttering.” These episodes occur 1 to 2 times per week, last for up to several hours, and are associated with mild shortness of breath and reduced activity tolerance. She is widowed and lives in a retirement facility, but she is independent in activities of daily living. She has fallen twice in the past year without significant injury.

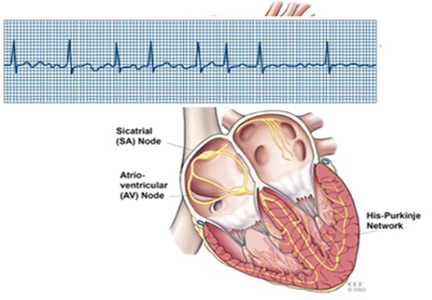

Physical examination is unremarkable. An electrocardiogram demonstrates sinus rhythm with left ventricular hypertrophy. A 30-day event monitor reveals several episodes of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation that correspond with her symptoms. A subsequent echocardiogram shows normal left ventricular systolic function, mild diastolic dysfunction, and no significant valvular abnormalities. Laboratory studies, including thyroid-stimulating hormone, are normal.

What is this patient’s risk of stroke? What is her risk of major bleeding from anticoagulation? How should fall risk be addressed in the decision-making process? What other factors should be considered?

AGE, ATRIAL FIBRILLATION, AND STROKE RISK

The prevalence of atrial fibrillation increases with age, and nearly half of patients with atrial fibrillation in the United States are 75 or older.1 In addition, older age is an independent risk factor for stroke in patients with atrial fibrillation, and the proportion of strokes attributable to atrial fibrillation increases exponentially with age:

- 1.5% at age 50 to 59

- 2.8% at age 60 to 69

- 9.9% at age 70 to 79

- 23.5% at age 80 to 89.2

Numerous large randomized trials have shown that anticoagulation with warfarin reduces the risk of stroke by about two-thirds in patients with atrial fibrillation, and that this benefit extends to the elderly.

In the Birmingham Atrial Fibrillation Treatment of the Aged trial,3 973 patients at least 75 years old (mean age 81.5, 55% male) were randomized to receive either warfarin with a target international normalized ratio of 2.0 to 3.0 or aspirin 75 mg/day. Over an average follow-up of 2.7 years, the composite outcome of fatal or disabling stroke, arterial embolism, or intracranial hemorrhage occurred in 24 (4.9%) of the 488 patients in the warfarin group and 48 (9.9%) of the 485 patients in the aspirin group (absolute yearly risk reduction 2%, 95% confidence interval 0.7–3.2, number needed to treat 50 for 1 year). Importantly, the benefit of warfarin was similar in men and women, and in patients ages 75 to 79, 80 to 84, and 85 and older.

More recently, the oral anticoagulants dabigatran, rivaroxaban, apixaban, and edoxaban have been shown to be at least as effective as warfarin with respect to both stroke prevention and major bleeding complications, and subgroup analyses have confirmed similar outcomes in older and younger patients.4,5

But despite the proven value of anticoagulation for stroke prevention in older adults, only 40% to 60% of older patients who are suitable candidates for anticoagulation actually receive it.6 Moreover, the proportion of patients who are treated declines progressively with age. The most frequently cited reason for nontreatment is perception of a high risk of falls and associated concerns about bleeding, especially intracranial hemorrhage.7–10

BALANCING STROKE RISK VS BLEEDING RISK

Balancing the risk of stroke against the risk of bleeding related to falls is a commonly encountered conundrum in older patients with atrial fibrillation.

Stroke risk

The CHADS2 score was, until recently, the most widely used method for assessing stroke risk in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. CHADS2 assigns 1 point each for congestive heart failure, hypertension, age ≥ 75, and diabetes, and 2 points for prior stroke or transient ischemic attack (range 0–6 points). Annual stroke risk based on the CHADS2 score ranges from about 2% to about 18%

(Table 1).11

The CHA2DS2-VASc score,12 a modification of CHADS2, appears to assess the risk of stroke more accurately, especially at the lower end of the scale, and recent guidelines for managing atrial fibrillation recommend using the CHA2DS2-VASc algorithm.13 CHA2DS2-VASc is similar to CHADS2, except that it assigns 1 point for ages 65 to 74, 2 points for ages 75 and older, 1 point for vascular disease (coronary artery disease, peripheral arterial disease, aortic aneurysm), and 1 point for female sex (Table 1).11,12

For both CHADS2 and CHA2DS2-VASc, systemic anticoagulation is recommended for patients who have a score of 2 or higher. Our patient’s CHADS2 score is 2, and her CHA2DS2-VASc score is 4, corresponding to an annual estimated stroke risk of 4% with both scores (Table 1). Note, however, that the CHA2DS2-VASc score provides more information at the lower end of the spectrum.

Bleeding risk

Several scoring systems for assessing bleeding risk have also been developed (Table 2).14–16 Of these, the HAS-BLED score has come to be used more widely in recent years.

Perhaps not surprisingly, some of the same factors associated with risk of stroke also predict increased risk of bleeding (eg, older age, hypertension, prior stroke).14 Note, however, that history of falling or high risk of falling is only included in one of the bleeding risk models (HEMORR2HAGES).15

These tools are somewhat limited by their lack of consideration of concomitant antiplatelet therapy (only included in HAS-BLED) or history of bleeding (only ATRIA16 considers major and minor bleeding, HEMORR2HAGES does not specify bleeding severity, and HAS-BLED only considers major bleeding). The models also fail to include medications such as antibiotics or antiarrhythmic agents, which are commonly used by older patients with atrial fibrillation and may increase bleeding risk. In addition, all bleeding risk scores were developed for warfarin, and their applicability to patients treated with the newer oral anticoagulants has not been established.

At the time of presentation, our patient has a HAS-BLED score of 2 (1 point each for age and hypertension), placing her at intermediate risk of bleeding.14

Fear the clot, not the bleed

So how does one balance the risk of stroke vs the risk of bleeding? An adage from the early days of thrombolytic therapy for acute myocardial infarction was “fear the clot, not the bleed.” In other words, in the present context the consequences of a thrombus embolizing from the heart to the brain are likely to be more devastating and more permanent than the consequences of anticoagulation-associated hemorrhage.

Support for this view is underscored by a 2015 study by Lip et al,17 who examined stroke and bleeding risks and outcomes in a large real-world population of patients age 75 and older. The analysis included 819 patients ages 85 to 89 and 386 patients age 90 and older. The key finding was that the oldest patients derived the greatest net benefit from anticoagulation.

Moreover, the Canadian stroke registry of 3,197 patients, mean age 79, showed that advanced age was a more potent risk factor for ischemic stroke than it was for hemorrhagic stroke.18

Thus, the benefit from anticoagulation in patients with atrial fibrillation does not appear to have an upper age limit.

FALLS AND ANTICOAGULATION

Falls are an important source of morbidity, disability, and activity curtailment in older adults and, like atrial fibrillation, the incidence and prevalence of falls increase with age. In community-dwelling adults age 65 and older, the overall proportion with at least 1 fall in the preceding year ranges from about 30% to 40%.19 However, the rate increases with age and exceeds 50% in nursing home residents.20

Although anticoagulation is associated with a higher risk of bleeding in patients who fall, the absolute risk is small.

In a study of older adults with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation, a history of falls or documented high risk of falling was associated with a risk of intracranial hemorrhage during follow-up that was 1.9 times higher.21 Importantly, however, this risk did not differ among patients treated with warfarin, aspirin, or no antithrombotic therapy. In this analysis, patients with a CHADS2 score of 2 or higher benefited from anticoagulation, whether or not they were considered to be at risk for falls.

In another study,22 it was estimated that an individual would have to fall 295 times in 1 year for the risk of fall-related major bleeding to outweigh the benefit of warfarin in reducing the risk of stroke.

Thus, based on available evidence, perception of a high risk of falling should not be construed as justification for withholding anticoagulation in older patients who are otherwise suitable candidates for such therapy.

AT WHAT POINT DOES BLEEDING RISK OUTWEIGH ANTICOAGULATION BENEFIT?

Absolute contraindications to anticoagulation include an intracranial hemorrhage or neurosurgical procedure with high risk for bleeding within the past 30 days, an intracranial neoplasm or vascular abnormality with high risk of bleeding, recurrent life-threatening gastrointestinal or other bleeding events, and severe bleeding disorders, including severe thrombocytopenia.

In patients with atrial fibrillation at high risk of bleeding as assessed by one of the bleeding risk scores and relatively low risk of ischemic stroke, the risk of anticoagulation may outweigh the benefit, although no studies have specifically addressed this issue.

In patients with frequent falls, including injurious falls, the benefits of anticoagulation usually outweigh the risks of bleeding, but management should incorporate interventions designed to mitigate fall risk.

Finally, in patients with a poor prognosis approaching the end of life, the risks and burdens of anticoagulation may exceed the perceived benefits, in which case discontinuation of anticoagulation may be appropriate.

SHOULD OUR PATIENT RECEIVE ANTICOAGULATION?

As noted above, our patient has a high risk of stroke and a moderate risk of bleeding, and multiple lines of evidence indicate that the benefits of anticoagulation (ie, prevention of stroke and systemic embolization) substantially outweigh the risks of bleeding. Although she has a history of falls, which may seem to muddy the waters, this factor should not play a major role in decision-making. Moreover, her advanced age should, if anything, be considered a point in favor of anticoagulation. So from the scientific standpoint, anticoagulation is the clear winner.

A shared decision

But that is not the end of the story. Since there is tension between benefits and risks with either approach (ie, anticoagulation or no anticoagulation), it is important to discuss the issues and options with the patient and relevant caregivers. Most older adults have witnessed the ravages of stroke in a friend or relative, and a recent study showed that most would be willing to accept a modest risk of bleeding to prevent a stroke.23

However, this is ultimately a personal decision for each patient, and in accordance with the principle of patient autonomy, the patient’s expressed wishes should be honored by using a process of shared decision-making.

Which anticoagulant?

Finally, what about the choice of anticoagulation? The complexities of using warfarin, including its narrow therapeutic range and myriad interactions with other medications and foods, can make it a less appealing option for both patient and provider.

We recommend a novel oral anticoagulant as first-line therapy in the absence of contraindications such as severe renal insufficiency, and prefer apixaban because it is the only agent shown to be superior to warfarin with respect to both stroke prevention and bleeding risk.24

Important disadvantages of the novel oral anticoagulants include their higher cost and lack of an effective antidote in the event of clinically significant bleeding (with the exception of idarucizumab, which was recently approved for reversal of serious bleeding associated with dabigatran), issues that may be of particular concern to older adults. While there is no therapeutic range to monitor for the newer agents, more frequent monitoring for occult anemia may be needed.

Thus, selection of an anticoagulant should also be individualized through shared decision-making.

Is aspirin alone an alternative?

And what if the patient chooses to forgo anticoagulation? In that case, aspirin 75 to 325 mg/day may seem reasonable, but there is scant evidence that aspirin is beneficial for stroke prevention in patients with atrial fibrillation in this age group, and aspirin, too, is associated with an increased risk of bleeding.25

As a result, current US and European guidelines recommend a very limited role for aspirin as a single agent in the management of atrial fibrillation.26 The joint 2014 guidelines of the American Heart Association, American College of Cardiology, and Heart Rhythm Society give aspirin a class IIB recommendation (ie, it “may” be considered), level of evidence C (ie, very limited) for use as an alternative to no antithrombotic therapy or systemic anticoagulation only in patients with a CHA2DS2-VASc score of 1, thereby excluding all patients age 75 and older.13

In most cases, aspirin as sole prophylaxis against stroke in atrial fibrillation should be avoided in the absence of another indication for its use, such as coexisting coronary artery disease or peripheral arterial disease.

A COMPLEX DECISION

In summary, the decisions surrounding anticoagulation of elderly patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation are complex. Accurate assessment of stroke risk is key, and although bleeding risk is also an essential consideration, it is important not to overemphasize bleeding and fall risks in the decision-making process.

- Go AS, Hylek EM, Phillips KA, et al. Prevalence of diagnosed atrial fibrillation in adults: national implications for rhythm management and stroke prevention: the AnTicoagulation and Risk Factors in Atrial Fibrillation (ATRIA) Study. JAMA 2001; 285:2370–2375.

- Wolf PA, Abbott RD, Kannel WB. Atrial fibrillation as an independent risk factor for stroke: the Framingham Study. Stroke 1991; 22:983–988.

- Mant J, Hobbs FD, Fletcher K, et al; BAFTA investigators; Midland Research Practices Network (MidReC). Warfarin versus aspirin for stroke prevention in an elderly community population with atrial fibrillation (the Birmingham Atrial Fibrillation Treatment of the Aged Study, BAFTA): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2007; 370:493–503.

- Chatterjee S, Sardar P, Biondi-Zoccai G, Kumbhani DJ. New oral anticoagulants and the risk of intracranial hemorrhage: traditional and Bayesian meta-analysis and mixed treatment comparison of randomized trials of new oral anticoagulants in atrial fibrillation. JAMA Neurology 2013; 70:1486–1490.

- Sardar P, Chatterjee S, Chaudhari S, Lip GY. New oral anticoagulants in elderly adults: evidence from a meta-analysis of randomized trials. J Am Geriatr Soc 2014; 62:857–864.

- Rich MW. Atrial fibrillation in long term care. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2012; 13:688–691.

- McCrory DC, Matchar DB, Samsa G, Sanders LL, Pritchett EL. Physician attitudes about anticoagulation for nonvalvular atrial fibrillation in the elderly. Arch Intern Med 1995; 155:277–281.

- Pugh D, Pugh J, Mead GE. Attitudes of physicians regarding anticoagulation for atrial fibrillation: a systematic review. Age Ageing 2011; 40:675–683.

- Sellers MB, Newby LK. Atrial fibrillation, anticoagulation, fall risk, and outcomes in elderly patients. Am Heart J 2011; 161:241–246.

- Bahri O, Roca F, Lechani T, et al. Underuse of oral anticoagulation for individuals with atrial fibrillation in a nursing home setting in France: comparisons of resident characteristics and physician attitude. J Am Geriatr Soc 2015; 63:71–76.

- Gage BF, Waterman AD, Shannon W, Boechler M, Rich MW, Radford MJ. Validation of clinical classification schemes for predicting stroke: results from the National Registry of Atrial Fibrillation. JAMA 2001; 285:2864–2870.

- Lip GY, Nieuwlaat R, Pisters R, Lane DA, Crijns HJ. Refining clinical risk stratification for predicting stroke and thromboembolism in atrial fibrillation using a novel risk factor-based approach: the Euro Heart Survey on Atrial Fibrillation. Chest 2010; 137:263–272.

- January CT, Wann LS, Alpert JS, et al; American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014; 64:e1–e76.

- Pisters R, Lane DA, Nieuwlaat R, de Vos CB, Crijns HJ, Lip GY. A novel user-friendly score (HAS-BLED) to assess 1-year risk of major bleeding in patients with atrial fibrillation: the Euro Heart Survey. Chest 2010; 138:1093–1100.

- Gage BF, Yan Y, Milligan PE, et al. Clinical classification schemes for predicting hemorrhage: results from the National Registry of Atrial Fibrillation (NRAF). Am Heart J 2006; 151:713–719.

- Fang MC, Go AS, Chang Y, et al. A new risk scheme to predict warfarin-associated hemorrhage: The ATRIA (Anticoagulation and Risk Factors in Atrial Fibrillation) Study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011; 58:395–401.

- Lip GY, Clementy N, Pericart L, Banerjee A, Fauchier L. Stroke and major bleeding risk in elderly patients aged ≥ 75 years with atrial fibrillation: the Loire Valley atrial fibrillation project. Stroke 2015; 46:143–150.

- McGrath ER, Kapral MK, Fang J, et al; Investigators of the Registry of the Canadian Stroke Network. Which risk factors are more associated with ischemic stroke than intracerebral hemorrhage in patients with atrial fibrillation? Stroke 2012; 43:2048–2054.

- Phelan EA, Mahoney JE, Voit JC, Stevens JA. Assessment and management of fall risk in primary care settings. Med Clin North Am 2015; 99:281–293.

- Deandrea S, Bravi F, Turati F, Lucenteforte E, La Vecchia C, Negri E. Risk factors for falls in older people in nursing homes and hospitals. A systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2013; 56:407–415.

- Gage BF, Birman-Deych E, Kerzner R, Radford MJ, Nilasena DS, Rich MW. Incidence of intracranial hemorrhage in patients with atrial fibrillation who are prone to fall. Am J Med 2005; 118:612–617.

- Man-Son-Hing M, Nichol G, Lau A, Laupacis A. Choosing antithrombotic therapy for elderly patients with atrial fibrillation who are at risk for falls. Arch Intern Med 1999; 159:677–685.

- Riva N, Smith DE, Lip GY, Lane DA. Advancing age and bleeding risk are the strongest barriers to anticoagulant prescription in atrial fibrillation. Age Ageing 2011; 40:653–655.

- De Caterina R, Andersson U, Alexander JH, et al; ARISTOTLE Investigators. History of bleeding and outcomes with apixaban versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation in the Apixaban for Reduction in Stroke and Other Thromboembolic Events in Atrial Fibrillation trial. Am Heart J 2016; 175:175–183.

- Ben Freedman S, Gersh BJ, Lip GY. Misperceptions of aspirin efficacy and safety may perpetuate anticoagulant underutilization in atrial fibrillation. Eur Heart J 2015; 36:653–656.

- Camm AJ, Lip GY, De Caterina R, et al; ESC Committee for Practice Guidelines (CPG). 2012 focused update of the ESC Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation: an update of the 2010 ESC Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation. Developed with the special contribution of the European Heart Rhythm Association. Eur Heart J 2012; 33:2719–2747.

An 86-year-old woman with hypertension, osteoporosis, and mild cognitive impairment presents with episodes of palpitations and heart “fluttering.” These episodes occur 1 to 2 times per week, last for up to several hours, and are associated with mild shortness of breath and reduced activity tolerance. She is widowed and lives in a retirement facility, but she is independent in activities of daily living. She has fallen twice in the past year without significant injury.

Physical examination is unremarkable. An electrocardiogram demonstrates sinus rhythm with left ventricular hypertrophy. A 30-day event monitor reveals several episodes of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation that correspond with her symptoms. A subsequent echocardiogram shows normal left ventricular systolic function, mild diastolic dysfunction, and no significant valvular abnormalities. Laboratory studies, including thyroid-stimulating hormone, are normal.

What is this patient’s risk of stroke? What is her risk of major bleeding from anticoagulation? How should fall risk be addressed in the decision-making process? What other factors should be considered?

AGE, ATRIAL FIBRILLATION, AND STROKE RISK

The prevalence of atrial fibrillation increases with age, and nearly half of patients with atrial fibrillation in the United States are 75 or older.1 In addition, older age is an independent risk factor for stroke in patients with atrial fibrillation, and the proportion of strokes attributable to atrial fibrillation increases exponentially with age:

- 1.5% at age 50 to 59

- 2.8% at age 60 to 69

- 9.9% at age 70 to 79

- 23.5% at age 80 to 89.2

Numerous large randomized trials have shown that anticoagulation with warfarin reduces the risk of stroke by about two-thirds in patients with atrial fibrillation, and that this benefit extends to the elderly.

In the Birmingham Atrial Fibrillation Treatment of the Aged trial,3 973 patients at least 75 years old (mean age 81.5, 55% male) were randomized to receive either warfarin with a target international normalized ratio of 2.0 to 3.0 or aspirin 75 mg/day. Over an average follow-up of 2.7 years, the composite outcome of fatal or disabling stroke, arterial embolism, or intracranial hemorrhage occurred in 24 (4.9%) of the 488 patients in the warfarin group and 48 (9.9%) of the 485 patients in the aspirin group (absolute yearly risk reduction 2%, 95% confidence interval 0.7–3.2, number needed to treat 50 for 1 year). Importantly, the benefit of warfarin was similar in men and women, and in patients ages 75 to 79, 80 to 84, and 85 and older.

More recently, the oral anticoagulants dabigatran, rivaroxaban, apixaban, and edoxaban have been shown to be at least as effective as warfarin with respect to both stroke prevention and major bleeding complications, and subgroup analyses have confirmed similar outcomes in older and younger patients.4,5

But despite the proven value of anticoagulation for stroke prevention in older adults, only 40% to 60% of older patients who are suitable candidates for anticoagulation actually receive it.6 Moreover, the proportion of patients who are treated declines progressively with age. The most frequently cited reason for nontreatment is perception of a high risk of falls and associated concerns about bleeding, especially intracranial hemorrhage.7–10

BALANCING STROKE RISK VS BLEEDING RISK

Balancing the risk of stroke against the risk of bleeding related to falls is a commonly encountered conundrum in older patients with atrial fibrillation.

Stroke risk

The CHADS2 score was, until recently, the most widely used method for assessing stroke risk in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. CHADS2 assigns 1 point each for congestive heart failure, hypertension, age ≥ 75, and diabetes, and 2 points for prior stroke or transient ischemic attack (range 0–6 points). Annual stroke risk based on the CHADS2 score ranges from about 2% to about 18%

(Table 1).11

The CHA2DS2-VASc score,12 a modification of CHADS2, appears to assess the risk of stroke more accurately, especially at the lower end of the scale, and recent guidelines for managing atrial fibrillation recommend using the CHA2DS2-VASc algorithm.13 CHA2DS2-VASc is similar to CHADS2, except that it assigns 1 point for ages 65 to 74, 2 points for ages 75 and older, 1 point for vascular disease (coronary artery disease, peripheral arterial disease, aortic aneurysm), and 1 point for female sex (Table 1).11,12

For both CHADS2 and CHA2DS2-VASc, systemic anticoagulation is recommended for patients who have a score of 2 or higher. Our patient’s CHADS2 score is 2, and her CHA2DS2-VASc score is 4, corresponding to an annual estimated stroke risk of 4% with both scores (Table 1). Note, however, that the CHA2DS2-VASc score provides more information at the lower end of the spectrum.

Bleeding risk

Several scoring systems for assessing bleeding risk have also been developed (Table 2).14–16 Of these, the HAS-BLED score has come to be used more widely in recent years.

Perhaps not surprisingly, some of the same factors associated with risk of stroke also predict increased risk of bleeding (eg, older age, hypertension, prior stroke).14 Note, however, that history of falling or high risk of falling is only included in one of the bleeding risk models (HEMORR2HAGES).15

These tools are somewhat limited by their lack of consideration of concomitant antiplatelet therapy (only included in HAS-BLED) or history of bleeding (only ATRIA16 considers major and minor bleeding, HEMORR2HAGES does not specify bleeding severity, and HAS-BLED only considers major bleeding). The models also fail to include medications such as antibiotics or antiarrhythmic agents, which are commonly used by older patients with atrial fibrillation and may increase bleeding risk. In addition, all bleeding risk scores were developed for warfarin, and their applicability to patients treated with the newer oral anticoagulants has not been established.

At the time of presentation, our patient has a HAS-BLED score of 2 (1 point each for age and hypertension), placing her at intermediate risk of bleeding.14

Fear the clot, not the bleed

So how does one balance the risk of stroke vs the risk of bleeding? An adage from the early days of thrombolytic therapy for acute myocardial infarction was “fear the clot, not the bleed.” In other words, in the present context the consequences of a thrombus embolizing from the heart to the brain are likely to be more devastating and more permanent than the consequences of anticoagulation-associated hemorrhage.

Support for this view is underscored by a 2015 study by Lip et al,17 who examined stroke and bleeding risks and outcomes in a large real-world population of patients age 75 and older. The analysis included 819 patients ages 85 to 89 and 386 patients age 90 and older. The key finding was that the oldest patients derived the greatest net benefit from anticoagulation.

Moreover, the Canadian stroke registry of 3,197 patients, mean age 79, showed that advanced age was a more potent risk factor for ischemic stroke than it was for hemorrhagic stroke.18

Thus, the benefit from anticoagulation in patients with atrial fibrillation does not appear to have an upper age limit.

FALLS AND ANTICOAGULATION

Falls are an important source of morbidity, disability, and activity curtailment in older adults and, like atrial fibrillation, the incidence and prevalence of falls increase with age. In community-dwelling adults age 65 and older, the overall proportion with at least 1 fall in the preceding year ranges from about 30% to 40%.19 However, the rate increases with age and exceeds 50% in nursing home residents.20

Although anticoagulation is associated with a higher risk of bleeding in patients who fall, the absolute risk is small.

In a study of older adults with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation, a history of falls or documented high risk of falling was associated with a risk of intracranial hemorrhage during follow-up that was 1.9 times higher.21 Importantly, however, this risk did not differ among patients treated with warfarin, aspirin, or no antithrombotic therapy. In this analysis, patients with a CHADS2 score of 2 or higher benefited from anticoagulation, whether or not they were considered to be at risk for falls.

In another study,22 it was estimated that an individual would have to fall 295 times in 1 year for the risk of fall-related major bleeding to outweigh the benefit of warfarin in reducing the risk of stroke.

Thus, based on available evidence, perception of a high risk of falling should not be construed as justification for withholding anticoagulation in older patients who are otherwise suitable candidates for such therapy.

AT WHAT POINT DOES BLEEDING RISK OUTWEIGH ANTICOAGULATION BENEFIT?

Absolute contraindications to anticoagulation include an intracranial hemorrhage or neurosurgical procedure with high risk for bleeding within the past 30 days, an intracranial neoplasm or vascular abnormality with high risk of bleeding, recurrent life-threatening gastrointestinal or other bleeding events, and severe bleeding disorders, including severe thrombocytopenia.

In patients with atrial fibrillation at high risk of bleeding as assessed by one of the bleeding risk scores and relatively low risk of ischemic stroke, the risk of anticoagulation may outweigh the benefit, although no studies have specifically addressed this issue.

In patients with frequent falls, including injurious falls, the benefits of anticoagulation usually outweigh the risks of bleeding, but management should incorporate interventions designed to mitigate fall risk.

Finally, in patients with a poor prognosis approaching the end of life, the risks and burdens of anticoagulation may exceed the perceived benefits, in which case discontinuation of anticoagulation may be appropriate.

SHOULD OUR PATIENT RECEIVE ANTICOAGULATION?

As noted above, our patient has a high risk of stroke and a moderate risk of bleeding, and multiple lines of evidence indicate that the benefits of anticoagulation (ie, prevention of stroke and systemic embolization) substantially outweigh the risks of bleeding. Although she has a history of falls, which may seem to muddy the waters, this factor should not play a major role in decision-making. Moreover, her advanced age should, if anything, be considered a point in favor of anticoagulation. So from the scientific standpoint, anticoagulation is the clear winner.

A shared decision

But that is not the end of the story. Since there is tension between benefits and risks with either approach (ie, anticoagulation or no anticoagulation), it is important to discuss the issues and options with the patient and relevant caregivers. Most older adults have witnessed the ravages of stroke in a friend or relative, and a recent study showed that most would be willing to accept a modest risk of bleeding to prevent a stroke.23

However, this is ultimately a personal decision for each patient, and in accordance with the principle of patient autonomy, the patient’s expressed wishes should be honored by using a process of shared decision-making.

Which anticoagulant?

Finally, what about the choice of anticoagulation? The complexities of using warfarin, including its narrow therapeutic range and myriad interactions with other medications and foods, can make it a less appealing option for both patient and provider.

We recommend a novel oral anticoagulant as first-line therapy in the absence of contraindications such as severe renal insufficiency, and prefer apixaban because it is the only agent shown to be superior to warfarin with respect to both stroke prevention and bleeding risk.24

Important disadvantages of the novel oral anticoagulants include their higher cost and lack of an effective antidote in the event of clinically significant bleeding (with the exception of idarucizumab, which was recently approved for reversal of serious bleeding associated with dabigatran), issues that may be of particular concern to older adults. While there is no therapeutic range to monitor for the newer agents, more frequent monitoring for occult anemia may be needed.

Thus, selection of an anticoagulant should also be individualized through shared decision-making.

Is aspirin alone an alternative?

And what if the patient chooses to forgo anticoagulation? In that case, aspirin 75 to 325 mg/day may seem reasonable, but there is scant evidence that aspirin is beneficial for stroke prevention in patients with atrial fibrillation in this age group, and aspirin, too, is associated with an increased risk of bleeding.25

As a result, current US and European guidelines recommend a very limited role for aspirin as a single agent in the management of atrial fibrillation.26 The joint 2014 guidelines of the American Heart Association, American College of Cardiology, and Heart Rhythm Society give aspirin a class IIB recommendation (ie, it “may” be considered), level of evidence C (ie, very limited) for use as an alternative to no antithrombotic therapy or systemic anticoagulation only in patients with a CHA2DS2-VASc score of 1, thereby excluding all patients age 75 and older.13

In most cases, aspirin as sole prophylaxis against stroke in atrial fibrillation should be avoided in the absence of another indication for its use, such as coexisting coronary artery disease or peripheral arterial disease.

A COMPLEX DECISION

In summary, the decisions surrounding anticoagulation of elderly patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation are complex. Accurate assessment of stroke risk is key, and although bleeding risk is also an essential consideration, it is important not to overemphasize bleeding and fall risks in the decision-making process.

An 86-year-old woman with hypertension, osteoporosis, and mild cognitive impairment presents with episodes of palpitations and heart “fluttering.” These episodes occur 1 to 2 times per week, last for up to several hours, and are associated with mild shortness of breath and reduced activity tolerance. She is widowed and lives in a retirement facility, but she is independent in activities of daily living. She has fallen twice in the past year without significant injury.

Physical examination is unremarkable. An electrocardiogram demonstrates sinus rhythm with left ventricular hypertrophy. A 30-day event monitor reveals several episodes of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation that correspond with her symptoms. A subsequent echocardiogram shows normal left ventricular systolic function, mild diastolic dysfunction, and no significant valvular abnormalities. Laboratory studies, including thyroid-stimulating hormone, are normal.

What is this patient’s risk of stroke? What is her risk of major bleeding from anticoagulation? How should fall risk be addressed in the decision-making process? What other factors should be considered?

AGE, ATRIAL FIBRILLATION, AND STROKE RISK

The prevalence of atrial fibrillation increases with age, and nearly half of patients with atrial fibrillation in the United States are 75 or older.1 In addition, older age is an independent risk factor for stroke in patients with atrial fibrillation, and the proportion of strokes attributable to atrial fibrillation increases exponentially with age:

- 1.5% at age 50 to 59

- 2.8% at age 60 to 69

- 9.9% at age 70 to 79

- 23.5% at age 80 to 89.2

Numerous large randomized trials have shown that anticoagulation with warfarin reduces the risk of stroke by about two-thirds in patients with atrial fibrillation, and that this benefit extends to the elderly.

In the Birmingham Atrial Fibrillation Treatment of the Aged trial,3 973 patients at least 75 years old (mean age 81.5, 55% male) were randomized to receive either warfarin with a target international normalized ratio of 2.0 to 3.0 or aspirin 75 mg/day. Over an average follow-up of 2.7 years, the composite outcome of fatal or disabling stroke, arterial embolism, or intracranial hemorrhage occurred in 24 (4.9%) of the 488 patients in the warfarin group and 48 (9.9%) of the 485 patients in the aspirin group (absolute yearly risk reduction 2%, 95% confidence interval 0.7–3.2, number needed to treat 50 for 1 year). Importantly, the benefit of warfarin was similar in men and women, and in patients ages 75 to 79, 80 to 84, and 85 and older.

More recently, the oral anticoagulants dabigatran, rivaroxaban, apixaban, and edoxaban have been shown to be at least as effective as warfarin with respect to both stroke prevention and major bleeding complications, and subgroup analyses have confirmed similar outcomes in older and younger patients.4,5

But despite the proven value of anticoagulation for stroke prevention in older adults, only 40% to 60% of older patients who are suitable candidates for anticoagulation actually receive it.6 Moreover, the proportion of patients who are treated declines progressively with age. The most frequently cited reason for nontreatment is perception of a high risk of falls and associated concerns about bleeding, especially intracranial hemorrhage.7–10

BALANCING STROKE RISK VS BLEEDING RISK

Balancing the risk of stroke against the risk of bleeding related to falls is a commonly encountered conundrum in older patients with atrial fibrillation.

Stroke risk

The CHADS2 score was, until recently, the most widely used method for assessing stroke risk in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. CHADS2 assigns 1 point each for congestive heart failure, hypertension, age ≥ 75, and diabetes, and 2 points for prior stroke or transient ischemic attack (range 0–6 points). Annual stroke risk based on the CHADS2 score ranges from about 2% to about 18%

(Table 1).11

The CHA2DS2-VASc score,12 a modification of CHADS2, appears to assess the risk of stroke more accurately, especially at the lower end of the scale, and recent guidelines for managing atrial fibrillation recommend using the CHA2DS2-VASc algorithm.13 CHA2DS2-VASc is similar to CHADS2, except that it assigns 1 point for ages 65 to 74, 2 points for ages 75 and older, 1 point for vascular disease (coronary artery disease, peripheral arterial disease, aortic aneurysm), and 1 point for female sex (Table 1).11,12

For both CHADS2 and CHA2DS2-VASc, systemic anticoagulation is recommended for patients who have a score of 2 or higher. Our patient’s CHADS2 score is 2, and her CHA2DS2-VASc score is 4, corresponding to an annual estimated stroke risk of 4% with both scores (Table 1). Note, however, that the CHA2DS2-VASc score provides more information at the lower end of the spectrum.

Bleeding risk

Several scoring systems for assessing bleeding risk have also been developed (Table 2).14–16 Of these, the HAS-BLED score has come to be used more widely in recent years.

Perhaps not surprisingly, some of the same factors associated with risk of stroke also predict increased risk of bleeding (eg, older age, hypertension, prior stroke).14 Note, however, that history of falling or high risk of falling is only included in one of the bleeding risk models (HEMORR2HAGES).15

These tools are somewhat limited by their lack of consideration of concomitant antiplatelet therapy (only included in HAS-BLED) or history of bleeding (only ATRIA16 considers major and minor bleeding, HEMORR2HAGES does not specify bleeding severity, and HAS-BLED only considers major bleeding). The models also fail to include medications such as antibiotics or antiarrhythmic agents, which are commonly used by older patients with atrial fibrillation and may increase bleeding risk. In addition, all bleeding risk scores were developed for warfarin, and their applicability to patients treated with the newer oral anticoagulants has not been established.

At the time of presentation, our patient has a HAS-BLED score of 2 (1 point each for age and hypertension), placing her at intermediate risk of bleeding.14

Fear the clot, not the bleed

So how does one balance the risk of stroke vs the risk of bleeding? An adage from the early days of thrombolytic therapy for acute myocardial infarction was “fear the clot, not the bleed.” In other words, in the present context the consequences of a thrombus embolizing from the heart to the brain are likely to be more devastating and more permanent than the consequences of anticoagulation-associated hemorrhage.

Support for this view is underscored by a 2015 study by Lip et al,17 who examined stroke and bleeding risks and outcomes in a large real-world population of patients age 75 and older. The analysis included 819 patients ages 85 to 89 and 386 patients age 90 and older. The key finding was that the oldest patients derived the greatest net benefit from anticoagulation.

Moreover, the Canadian stroke registry of 3,197 patients, mean age 79, showed that advanced age was a more potent risk factor for ischemic stroke than it was for hemorrhagic stroke.18

Thus, the benefit from anticoagulation in patients with atrial fibrillation does not appear to have an upper age limit.

FALLS AND ANTICOAGULATION

Falls are an important source of morbidity, disability, and activity curtailment in older adults and, like atrial fibrillation, the incidence and prevalence of falls increase with age. In community-dwelling adults age 65 and older, the overall proportion with at least 1 fall in the preceding year ranges from about 30% to 40%.19 However, the rate increases with age and exceeds 50% in nursing home residents.20

Although anticoagulation is associated with a higher risk of bleeding in patients who fall, the absolute risk is small.

In a study of older adults with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation, a history of falls or documented high risk of falling was associated with a risk of intracranial hemorrhage during follow-up that was 1.9 times higher.21 Importantly, however, this risk did not differ among patients treated with warfarin, aspirin, or no antithrombotic therapy. In this analysis, patients with a CHADS2 score of 2 or higher benefited from anticoagulation, whether or not they were considered to be at risk for falls.

In another study,22 it was estimated that an individual would have to fall 295 times in 1 year for the risk of fall-related major bleeding to outweigh the benefit of warfarin in reducing the risk of stroke.

Thus, based on available evidence, perception of a high risk of falling should not be construed as justification for withholding anticoagulation in older patients who are otherwise suitable candidates for such therapy.

AT WHAT POINT DOES BLEEDING RISK OUTWEIGH ANTICOAGULATION BENEFIT?

Absolute contraindications to anticoagulation include an intracranial hemorrhage or neurosurgical procedure with high risk for bleeding within the past 30 days, an intracranial neoplasm or vascular abnormality with high risk of bleeding, recurrent life-threatening gastrointestinal or other bleeding events, and severe bleeding disorders, including severe thrombocytopenia.

In patients with atrial fibrillation at high risk of bleeding as assessed by one of the bleeding risk scores and relatively low risk of ischemic stroke, the risk of anticoagulation may outweigh the benefit, although no studies have specifically addressed this issue.

In patients with frequent falls, including injurious falls, the benefits of anticoagulation usually outweigh the risks of bleeding, but management should incorporate interventions designed to mitigate fall risk.

Finally, in patients with a poor prognosis approaching the end of life, the risks and burdens of anticoagulation may exceed the perceived benefits, in which case discontinuation of anticoagulation may be appropriate.

SHOULD OUR PATIENT RECEIVE ANTICOAGULATION?

As noted above, our patient has a high risk of stroke and a moderate risk of bleeding, and multiple lines of evidence indicate that the benefits of anticoagulation (ie, prevention of stroke and systemic embolization) substantially outweigh the risks of bleeding. Although she has a history of falls, which may seem to muddy the waters, this factor should not play a major role in decision-making. Moreover, her advanced age should, if anything, be considered a point in favor of anticoagulation. So from the scientific standpoint, anticoagulation is the clear winner.

A shared decision

But that is not the end of the story. Since there is tension between benefits and risks with either approach (ie, anticoagulation or no anticoagulation), it is important to discuss the issues and options with the patient and relevant caregivers. Most older adults have witnessed the ravages of stroke in a friend or relative, and a recent study showed that most would be willing to accept a modest risk of bleeding to prevent a stroke.23

However, this is ultimately a personal decision for each patient, and in accordance with the principle of patient autonomy, the patient’s expressed wishes should be honored by using a process of shared decision-making.

Which anticoagulant?

Finally, what about the choice of anticoagulation? The complexities of using warfarin, including its narrow therapeutic range and myriad interactions with other medications and foods, can make it a less appealing option for both patient and provider.

We recommend a novel oral anticoagulant as first-line therapy in the absence of contraindications such as severe renal insufficiency, and prefer apixaban because it is the only agent shown to be superior to warfarin with respect to both stroke prevention and bleeding risk.24

Important disadvantages of the novel oral anticoagulants include their higher cost and lack of an effective antidote in the event of clinically significant bleeding (with the exception of idarucizumab, which was recently approved for reversal of serious bleeding associated with dabigatran), issues that may be of particular concern to older adults. While there is no therapeutic range to monitor for the newer agents, more frequent monitoring for occult anemia may be needed.

Thus, selection of an anticoagulant should also be individualized through shared decision-making.

Is aspirin alone an alternative?

And what if the patient chooses to forgo anticoagulation? In that case, aspirin 75 to 325 mg/day may seem reasonable, but there is scant evidence that aspirin is beneficial for stroke prevention in patients with atrial fibrillation in this age group, and aspirin, too, is associated with an increased risk of bleeding.25

As a result, current US and European guidelines recommend a very limited role for aspirin as a single agent in the management of atrial fibrillation.26 The joint 2014 guidelines of the American Heart Association, American College of Cardiology, and Heart Rhythm Society give aspirin a class IIB recommendation (ie, it “may” be considered), level of evidence C (ie, very limited) for use as an alternative to no antithrombotic therapy or systemic anticoagulation only in patients with a CHA2DS2-VASc score of 1, thereby excluding all patients age 75 and older.13

In most cases, aspirin as sole prophylaxis against stroke in atrial fibrillation should be avoided in the absence of another indication for its use, such as coexisting coronary artery disease or peripheral arterial disease.

A COMPLEX DECISION

In summary, the decisions surrounding anticoagulation of elderly patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation are complex. Accurate assessment of stroke risk is key, and although bleeding risk is also an essential consideration, it is important not to overemphasize bleeding and fall risks in the decision-making process.

- Go AS, Hylek EM, Phillips KA, et al. Prevalence of diagnosed atrial fibrillation in adults: national implications for rhythm management and stroke prevention: the AnTicoagulation and Risk Factors in Atrial Fibrillation (ATRIA) Study. JAMA 2001; 285:2370–2375.

- Wolf PA, Abbott RD, Kannel WB. Atrial fibrillation as an independent risk factor for stroke: the Framingham Study. Stroke 1991; 22:983–988.

- Mant J, Hobbs FD, Fletcher K, et al; BAFTA investigators; Midland Research Practices Network (MidReC). Warfarin versus aspirin for stroke prevention in an elderly community population with atrial fibrillation (the Birmingham Atrial Fibrillation Treatment of the Aged Study, BAFTA): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2007; 370:493–503.

- Chatterjee S, Sardar P, Biondi-Zoccai G, Kumbhani DJ. New oral anticoagulants and the risk of intracranial hemorrhage: traditional and Bayesian meta-analysis and mixed treatment comparison of randomized trials of new oral anticoagulants in atrial fibrillation. JAMA Neurology 2013; 70:1486–1490.

- Sardar P, Chatterjee S, Chaudhari S, Lip GY. New oral anticoagulants in elderly adults: evidence from a meta-analysis of randomized trials. J Am Geriatr Soc 2014; 62:857–864.

- Rich MW. Atrial fibrillation in long term care. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2012; 13:688–691.

- McCrory DC, Matchar DB, Samsa G, Sanders LL, Pritchett EL. Physician attitudes about anticoagulation for nonvalvular atrial fibrillation in the elderly. Arch Intern Med 1995; 155:277–281.

- Pugh D, Pugh J, Mead GE. Attitudes of physicians regarding anticoagulation for atrial fibrillation: a systematic review. Age Ageing 2011; 40:675–683.

- Sellers MB, Newby LK. Atrial fibrillation, anticoagulation, fall risk, and outcomes in elderly patients. Am Heart J 2011; 161:241–246.

- Bahri O, Roca F, Lechani T, et al. Underuse of oral anticoagulation for individuals with atrial fibrillation in a nursing home setting in France: comparisons of resident characteristics and physician attitude. J Am Geriatr Soc 2015; 63:71–76.

- Gage BF, Waterman AD, Shannon W, Boechler M, Rich MW, Radford MJ. Validation of clinical classification schemes for predicting stroke: results from the National Registry of Atrial Fibrillation. JAMA 2001; 285:2864–2870.

- Lip GY, Nieuwlaat R, Pisters R, Lane DA, Crijns HJ. Refining clinical risk stratification for predicting stroke and thromboembolism in atrial fibrillation using a novel risk factor-based approach: the Euro Heart Survey on Atrial Fibrillation. Chest 2010; 137:263–272.

- January CT, Wann LS, Alpert JS, et al; American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014; 64:e1–e76.

- Pisters R, Lane DA, Nieuwlaat R, de Vos CB, Crijns HJ, Lip GY. A novel user-friendly score (HAS-BLED) to assess 1-year risk of major bleeding in patients with atrial fibrillation: the Euro Heart Survey. Chest 2010; 138:1093–1100.

- Gage BF, Yan Y, Milligan PE, et al. Clinical classification schemes for predicting hemorrhage: results from the National Registry of Atrial Fibrillation (NRAF). Am Heart J 2006; 151:713–719.

- Fang MC, Go AS, Chang Y, et al. A new risk scheme to predict warfarin-associated hemorrhage: The ATRIA (Anticoagulation and Risk Factors in Atrial Fibrillation) Study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011; 58:395–401.

- Lip GY, Clementy N, Pericart L, Banerjee A, Fauchier L. Stroke and major bleeding risk in elderly patients aged ≥ 75 years with atrial fibrillation: the Loire Valley atrial fibrillation project. Stroke 2015; 46:143–150.

- McGrath ER, Kapral MK, Fang J, et al; Investigators of the Registry of the Canadian Stroke Network. Which risk factors are more associated with ischemic stroke than intracerebral hemorrhage in patients with atrial fibrillation? Stroke 2012; 43:2048–2054.

- Phelan EA, Mahoney JE, Voit JC, Stevens JA. Assessment and management of fall risk in primary care settings. Med Clin North Am 2015; 99:281–293.

- Deandrea S, Bravi F, Turati F, Lucenteforte E, La Vecchia C, Negri E. Risk factors for falls in older people in nursing homes and hospitals. A systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2013; 56:407–415.

- Gage BF, Birman-Deych E, Kerzner R, Radford MJ, Nilasena DS, Rich MW. Incidence of intracranial hemorrhage in patients with atrial fibrillation who are prone to fall. Am J Med 2005; 118:612–617.

- Man-Son-Hing M, Nichol G, Lau A, Laupacis A. Choosing antithrombotic therapy for elderly patients with atrial fibrillation who are at risk for falls. Arch Intern Med 1999; 159:677–685.

- Riva N, Smith DE, Lip GY, Lane DA. Advancing age and bleeding risk are the strongest barriers to anticoagulant prescription in atrial fibrillation. Age Ageing 2011; 40:653–655.

- De Caterina R, Andersson U, Alexander JH, et al; ARISTOTLE Investigators. History of bleeding and outcomes with apixaban versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation in the Apixaban for Reduction in Stroke and Other Thromboembolic Events in Atrial Fibrillation trial. Am Heart J 2016; 175:175–183.

- Ben Freedman S, Gersh BJ, Lip GY. Misperceptions of aspirin efficacy and safety may perpetuate anticoagulant underutilization in atrial fibrillation. Eur Heart J 2015; 36:653–656.

- Camm AJ, Lip GY, De Caterina R, et al; ESC Committee for Practice Guidelines (CPG). 2012 focused update of the ESC Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation: an update of the 2010 ESC Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation. Developed with the special contribution of the European Heart Rhythm Association. Eur Heart J 2012; 33:2719–2747.

- Go AS, Hylek EM, Phillips KA, et al. Prevalence of diagnosed atrial fibrillation in adults: national implications for rhythm management and stroke prevention: the AnTicoagulation and Risk Factors in Atrial Fibrillation (ATRIA) Study. JAMA 2001; 285:2370–2375.

- Wolf PA, Abbott RD, Kannel WB. Atrial fibrillation as an independent risk factor for stroke: the Framingham Study. Stroke 1991; 22:983–988.

- Mant J, Hobbs FD, Fletcher K, et al; BAFTA investigators; Midland Research Practices Network (MidReC). Warfarin versus aspirin for stroke prevention in an elderly community population with atrial fibrillation (the Birmingham Atrial Fibrillation Treatment of the Aged Study, BAFTA): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2007; 370:493–503.

- Chatterjee S, Sardar P, Biondi-Zoccai G, Kumbhani DJ. New oral anticoagulants and the risk of intracranial hemorrhage: traditional and Bayesian meta-analysis and mixed treatment comparison of randomized trials of new oral anticoagulants in atrial fibrillation. JAMA Neurology 2013; 70:1486–1490.

- Sardar P, Chatterjee S, Chaudhari S, Lip GY. New oral anticoagulants in elderly adults: evidence from a meta-analysis of randomized trials. J Am Geriatr Soc 2014; 62:857–864.

- Rich MW. Atrial fibrillation in long term care. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2012; 13:688–691.

- McCrory DC, Matchar DB, Samsa G, Sanders LL, Pritchett EL. Physician attitudes about anticoagulation for nonvalvular atrial fibrillation in the elderly. Arch Intern Med 1995; 155:277–281.

- Pugh D, Pugh J, Mead GE. Attitudes of physicians regarding anticoagulation for atrial fibrillation: a systematic review. Age Ageing 2011; 40:675–683.

- Sellers MB, Newby LK. Atrial fibrillation, anticoagulation, fall risk, and outcomes in elderly patients. Am Heart J 2011; 161:241–246.

- Bahri O, Roca F, Lechani T, et al. Underuse of oral anticoagulation for individuals with atrial fibrillation in a nursing home setting in France: comparisons of resident characteristics and physician attitude. J Am Geriatr Soc 2015; 63:71–76.

- Gage BF, Waterman AD, Shannon W, Boechler M, Rich MW, Radford MJ. Validation of clinical classification schemes for predicting stroke: results from the National Registry of Atrial Fibrillation. JAMA 2001; 285:2864–2870.

- Lip GY, Nieuwlaat R, Pisters R, Lane DA, Crijns HJ. Refining clinical risk stratification for predicting stroke and thromboembolism in atrial fibrillation using a novel risk factor-based approach: the Euro Heart Survey on Atrial Fibrillation. Chest 2010; 137:263–272.

- January CT, Wann LS, Alpert JS, et al; American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014; 64:e1–e76.

- Pisters R, Lane DA, Nieuwlaat R, de Vos CB, Crijns HJ, Lip GY. A novel user-friendly score (HAS-BLED) to assess 1-year risk of major bleeding in patients with atrial fibrillation: the Euro Heart Survey. Chest 2010; 138:1093–1100.

- Gage BF, Yan Y, Milligan PE, et al. Clinical classification schemes for predicting hemorrhage: results from the National Registry of Atrial Fibrillation (NRAF). Am Heart J 2006; 151:713–719.

- Fang MC, Go AS, Chang Y, et al. A new risk scheme to predict warfarin-associated hemorrhage: The ATRIA (Anticoagulation and Risk Factors in Atrial Fibrillation) Study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011; 58:395–401.

- Lip GY, Clementy N, Pericart L, Banerjee A, Fauchier L. Stroke and major bleeding risk in elderly patients aged ≥ 75 years with atrial fibrillation: the Loire Valley atrial fibrillation project. Stroke 2015; 46:143–150.

- McGrath ER, Kapral MK, Fang J, et al; Investigators of the Registry of the Canadian Stroke Network. Which risk factors are more associated with ischemic stroke than intracerebral hemorrhage in patients with atrial fibrillation? Stroke 2012; 43:2048–2054.

- Phelan EA, Mahoney JE, Voit JC, Stevens JA. Assessment and management of fall risk in primary care settings. Med Clin North Am 2015; 99:281–293.

- Deandrea S, Bravi F, Turati F, Lucenteforte E, La Vecchia C, Negri E. Risk factors for falls in older people in nursing homes and hospitals. A systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2013; 56:407–415.

- Gage BF, Birman-Deych E, Kerzner R, Radford MJ, Nilasena DS, Rich MW. Incidence of intracranial hemorrhage in patients with atrial fibrillation who are prone to fall. Am J Med 2005; 118:612–617.

- Man-Son-Hing M, Nichol G, Lau A, Laupacis A. Choosing antithrombotic therapy for elderly patients with atrial fibrillation who are at risk for falls. Arch Intern Med 1999; 159:677–685.

- Riva N, Smith DE, Lip GY, Lane DA. Advancing age and bleeding risk are the strongest barriers to anticoagulant prescription in atrial fibrillation. Age Ageing 2011; 40:653–655.

- De Caterina R, Andersson U, Alexander JH, et al; ARISTOTLE Investigators. History of bleeding and outcomes with apixaban versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation in the Apixaban for Reduction in Stroke and Other Thromboembolic Events in Atrial Fibrillation trial. Am Heart J 2016; 175:175–183.

- Ben Freedman S, Gersh BJ, Lip GY. Misperceptions of aspirin efficacy and safety may perpetuate anticoagulant underutilization in atrial fibrillation. Eur Heart J 2015; 36:653–656.

- Camm AJ, Lip GY, De Caterina R, et al; ESC Committee for Practice Guidelines (CPG). 2012 focused update of the ESC Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation: an update of the 2010 ESC Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation. Developed with the special contribution of the European Heart Rhythm Association. Eur Heart J 2012; 33:2719–2747.

KEY POINTS

- For most patients in this category, the benefits of anticoagulation outweigh the risks.

- Although they are not perfect, scoring systems have been developed to predict the risk of stroke without anticoagulation and the risk of bleeding with anticoagulation.

- The decision-making process is complex and should be shared with the patient and the patient’s family and caregivers.