User login

Febrile young infants are at high risk for serious bacterial infection (SBI) with reported rates of 8.5% to 12%, even higher in neonates 28 days of age.[1, 2, 3] As a result, febrile infants often undergo extensive diagnostic evaluation consisting of a combination of urine, blood, and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) testing.[4, 5, 6] Several clinical prediction algorithms use this diagnostic testing to identify febrile infants at low risk for SBI, but they differ with respect to age range, recommended testing, antibiotic administration, and threshold for hospitalization.[4, 5, 6] Additionally, the optimal management strategy for this population has not been defined.[7] Consequently, laboratory testing, antibiotic use, and hospitalization for febrile young infants vary widely among hospitals.[8, 9, 10]

Clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) are designed to implement evidence‐based care and reduce practice variability, with the goal of improving quality of care and optimizing costs.[11] Implementation of a CPG for management of febrile young infants in the Intermountain Healthcare System was associated with greater adherence to evidence‐based care and lower costs.[12] However, when strong evidence is lacking, different interpretations of febrile infant risk classification incorporated into local CPGs may be a major driver of the across‐hospital practice variation observed in prior studies.[8, 9] Understanding sources of variability as well as determining the association of CPGs with clinicians' practice patterns can help identify quality improvement opportunities, either through national benchmarking or local efforts.

Our primary objectives were to compare (1) recommendations of pediatric emergency departmentbased institutional CPGs for febrile young infants and (2) rates of urine, blood, CSF testing, hospitalization, and ceftriaxone use at emergency department (ED) discharge based upon CPG presence and the specific CPG recommendations. Our secondary objectives were to describe the association of CPGs with healthcare costs and return visits for SBI.

METHODS

Study Design

We used the Pediatric Health Information System (PHIS) to identify febrile infants 56 days of age who presented to the ED between January 1, 2013 and December 31, 2013. We also surveyed ED providers at participating PHIS hospitals. Informed consent was obtained from survey respondents. The institutional review board at Boston Children's Hospital approved the study protocol.

Clinical Practice Guideline Survey

We sent an electronic survey to medical directors or division directors at 37 pediatric EDs to determine whether their ED utilized a CPG for the management of the febrile young infant in 2013. If no response was received after the second attempt, we queried ED fellowship directors or other ED attending physicians at nonresponding hospitals. Survey items included the presence of a febrile young infant CPG, and if present, the year of implementation, ages targeted, and CPG content. As applicable, respondents were asked to share their CPG and/or provide the specific CPG recommendations.

We collected and managed survey data using the Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) electronic data capture tools hosted at Boston Children's Hospital. REDCap is a secure, Web‐based application designed to support data capture for research studies.[13]

Data Source

The PHIS database contains administrative data from 44 US children's hospitals. These hospitals, affiliated with the Children's Hospital Association, represent 85% of freestanding US children's hospitals.[14] Encrypted patient identifiers permit tracking of patients across encounters.[15] Data quality and integrity are assured jointly by the Children's Hospital Association and participating hospitals.[16] For this study, 7 hospitals were excluded due to incomplete ED data or known data‐quality issues.[17]

Patients

We identified study infants using the following International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision (ICD‐9) admission or discharge diagnosis codes for fever as defined previously[8, 9]: 780.6, 778.4, 780.60, or 780.61. We excluded infants with a complex chronic condition[18] and those transferred from another institution, as these infants may warrant a nonstandard evaluation and/or may have incomplete data. For infants with >1 ED visit for fever during the study period, repeat visits within 3 days of an index visit were considered a revisit for the same episode of illness; visits >3 days following an index visit were considered as a new index visit.

Study Definitions

From the PHIS database, we abstracted demographic characteristics (gender, race/ethnicity), insurance status, and region where the hospital was located (using US Census categories[19]). Billing codes were used to assess whether urine, blood, and CSF testing (as defined previously[9]) were performed during the ED evaluation. To account for ED visits that spanned the midnight hour, for hospitalized patients we considered any testing or treatment occurring on the initial or second hospital day to be performed in the ED; billing code data in PHIS are based upon calendar day and do not distinguish testing performed in the ED versus inpatient setting.[8, 9] Patients billed for observation care were classified as being hospitalized.[20, 21]

We identified the presence of an SBI using ICD‐9 diagnosis codes for the following infections as described previously[9]: urinary tract infection or pyelonephritis,[22] bacteremia or sepsis, bacterial meningitis,[16] pneumonia,[23] or bacterial enteritis. To assess return visits for SBI that required inpatient management, we defined an ED revisit for an SBI as a return visit within 3 days of ED discharge[24, 25] that resulted in hospitalization with an associated ICD‐9 discharge diagnosis code for an SBI.

Hospitals charges in PHIS database were adjusted for hospital location by using the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services price/wage index. Costs were estimated by applying hospital‐level cost‐to‐charge ratios to charge data.[26]

Measured Exposures

The primary exposure was the presence of an ED‐based CPG for management of the febrile young infant aged 28 days and 29 to 56 days; 56 days was used as the upper age limit as all of the CPGs included infants up to this age or beyond. Six institutions utilized CPGs with different thresholds to define the age categories (eg, dichotomized at 27 or 30 days); these CPGs were classified into the aforementioned age groups to permit comparisons across standardized age groups. We classified institutions based on the presence of a CPG. To assess differences in the application of low‐risk criteria, the CPGs were further classified a priori based upon specific recommendations around laboratory testing and hospitalization, as well as ceftriaxone use for infants aged 29 to 56 days discharged from the ED. CPGs were categorized based upon whether testing, hospitalization, and ceftriaxone use were: (1) recommended for all patients, (2) recommended only if patients were classified as high risk (absence of low‐risk criteria), (3) recommended against, or (4) recommended to consider at clinician discretion.

Outcome Measures

Measured outcomes were performance of urine, blood, CSF testing, and hospitalization rate, as well as rate of ceftriaxone use for discharged infants aged 29 to 56 days, 3‐day revisits for SBI, and costs per visit, which included hospitalization costs for admitted patients.

Data Analysis

We described continuous variables using median and interquartile range or range values and categorical variables using frequencies. We compared medians using Wilcoxon rank sum and categorical variables using a [2] test. We compared rates of testing, hospitalization, ceftriaxone use, and 3‐day revisits for SBI based on the presence of a CPG, and when present, the specific CPG recommendations. Costs per visit were compared between institutions with and without CPGs and assessed separately for admitted and discharged patients. To adjust for potential confounders and clustering of patients within hospitals, we used generalized estimating equations with logistic regression to generate adjusted odd ratios (aORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Models were adjusted for geographic region, payer, race, and gender. Statistical analyses were performed by using SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). We determined statistical significance as a 2‐tailed P value <0.05.

Febrile infants with bronchiolitis or a history of prematurity may be managed differently from full‐term febrile young infants without bronchiolitis.[6, 27] Therefore, we performed a subgroup analysis after exclusion of infants with an ICD‐9 discharge diagnosis code for bronchiolitis (466.11 and 466.19)[28] or prematurity (765).

Because our study included ED encounters in 2013, we repeated our analyses after exclusion of hospitals with CPGs implemented during the 2013 calendar year.

RESULTS

CPG by Institution

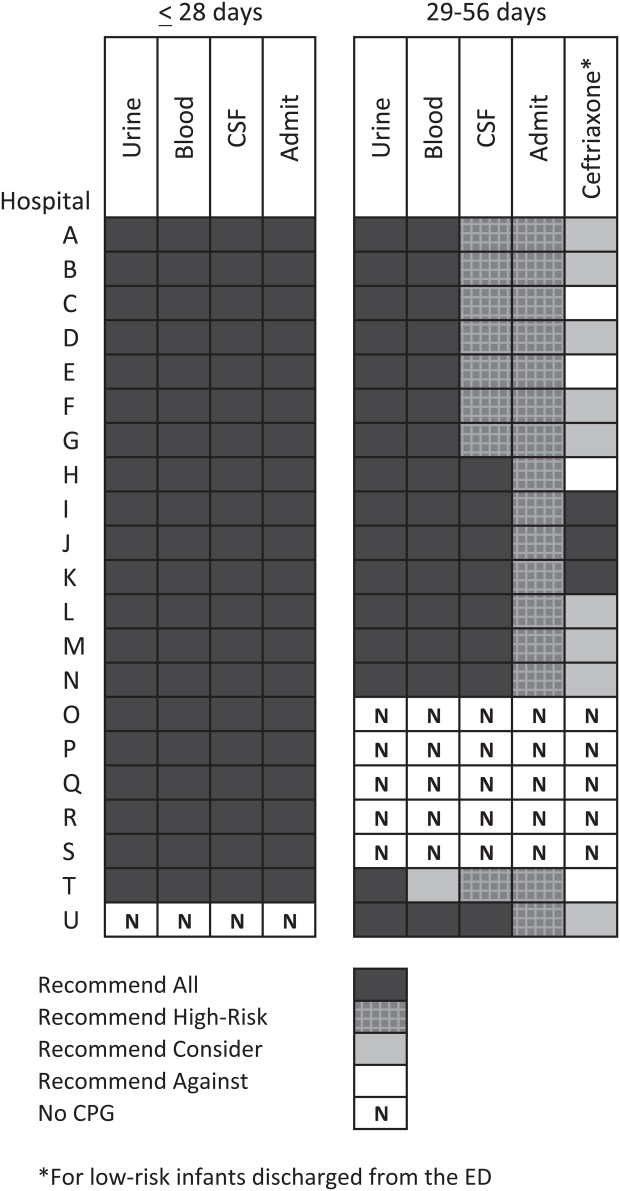

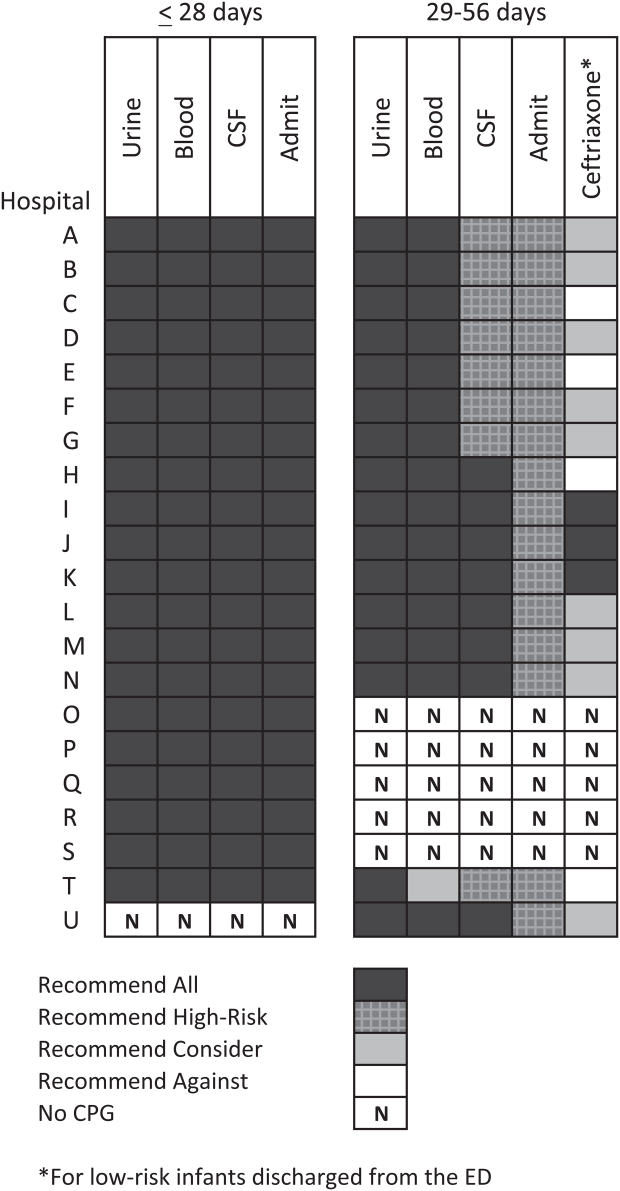

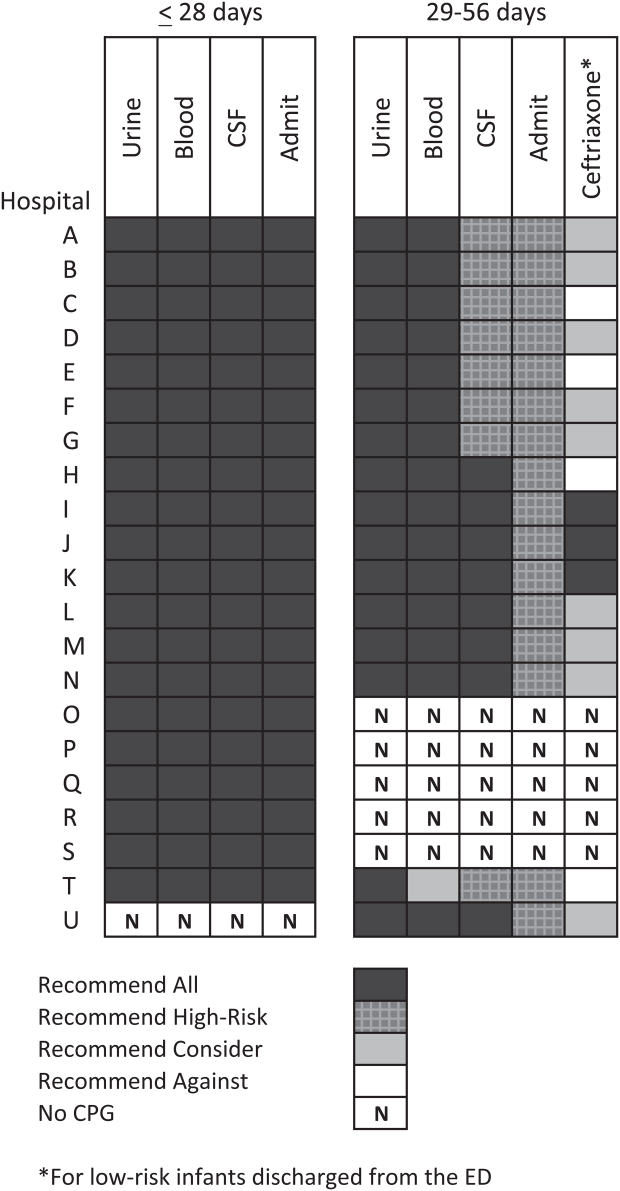

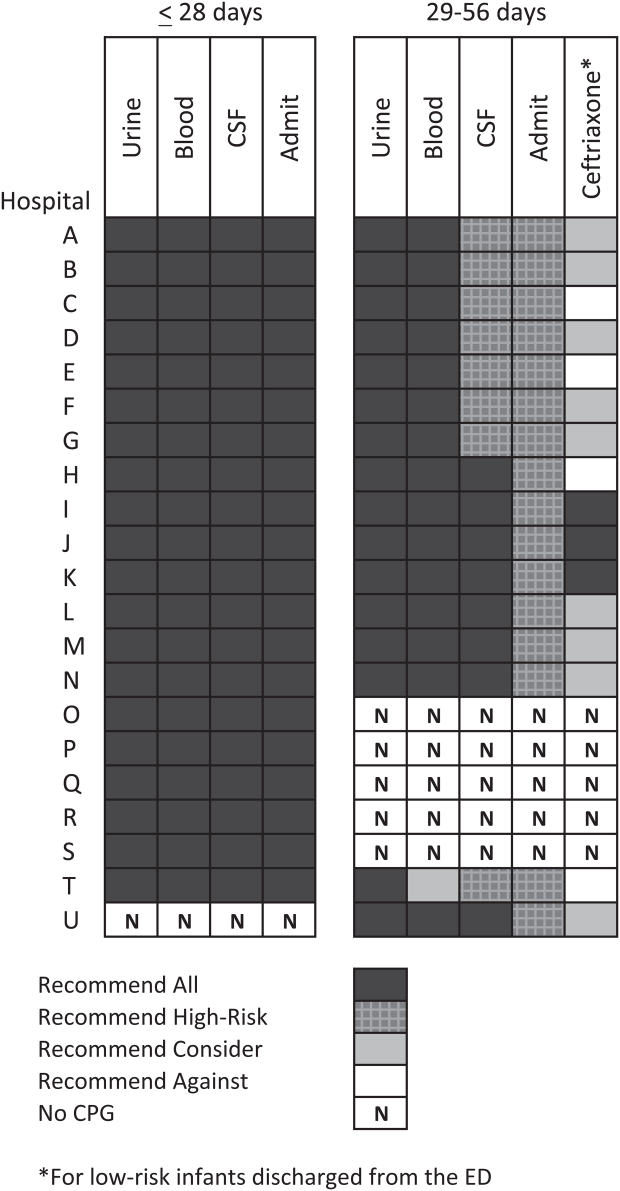

Thirty‐three (89.2%) of the 37 EDs surveyed completed the questionnaire. Overall, 21 (63.6%) of the 33 EDs had a CPG; 15 (45.5%) had a CPG for all infants 56 days of age, 5 (15.2%) had a CPG for infants 28 days only, and 1 (3.0%) had a CPG for infants 29 to 56 days but not 28 days of age (Figure 1). Seventeen EDs had an established CPG prior to 2013, and 4 hospitals implemented a CPG during the 2013 calendar year, 2 with CPGs for neonates 28 days and 2 with CPGs for both 28 days and 29 to 56 days of age. Hospitals with CPGs were more likely to be located in the Northeast and West regions of the United States and provide care to a higher proportion of non‐Hispanic white patients, as well as those with commercial insurance (Table 1).

| Characteristic | 28 Days | 2956 Days | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No CPG, n=996, N (%) | CPG, n=2,149, N (%) | P Value | No CPG, n=2,460, N (%) | CPG, n=3,772, N (%) | P Value | |

| ||||||

| Race | ||||||

| Non‐Hispanic white | 325 (32.6) | 996 (46.3) | 867 (35.2) | 1,728 (45.8) | ||

| Non‐Hispanic black | 248 (24.9) | 381 (17.7) | 593 (24.1) | 670 (17.8) | ||

| Hispanic | 243 (24.4) | 531 (24.7) | 655 (26.6) | 986 (26.1) | ||

| Asian | 28 (2.8) | 78 (3.6) | 40 (1.6) | 122 (3.2) | ||

| Other Race | 152 (15.3) | 163 (7.6) | <0.001 | 305 (12.4) | 266 (7.1) | <0.001 |

| Gender | ||||||

| Female | 435 (43.7) | 926 (43.1) | 0.76 | 1,067 (43.4) | 1,714 (45.4) | 0.22 |

| Payer | ||||||

| Commercial | 243 (24.4) | 738 (34.3) | 554 (22.5) | 1,202 (31.9) | ||

| Government | 664 (66.7) | 1,269 (59.1) | 1,798 (73.1) | 2,342 (62.1) | ||

| Other payer | 89 (8.9) | 142 (6.6) | <0.001 | 108 (4.4) | 228 (6.0) | <0.001 |

| Region | ||||||

| Northeast | 39 (3.9) | 245 (11.4) | 77 (3.1) | 572 (15.2) | ||

| South | 648 (65.1) | 915 (42.6) | 1,662 (67.6) | 1,462 (38.8) | ||

| Midwest | 271 (27.2) | 462 (21.5) | 506 (20.6) | 851 (22.6) | ||

| West | 38 (3.8) | 527 (24.5) | <0.001 | 215 (8.7) | 887 (23.5) | <0.001 |

| Serious bacterial infection | ||||||

| Overall* | 131 (13.2) | 242 (11.3) | 0.14 | 191 (7.8) | 237 (6.3) | 0.03 |

| UTI/pyelonephritis | 73 (7.3) | 153 (7.1) | 103 (4.2) | 154 (4.1) | ||

| Bacteremia/sepsis | 56 (5.6) | 91 (4.2) | 78 (3.2) | 61 (1.6) | ||

| Bacterial meningitis | 15 (1.5) | 15 (0.7) | 4 (0.2) | 14 (0.4) | ||

| Age, d, median (IQR) | 18 (11, 24) | 18 (11, 23) | 0.67 | 46 (37, 53) | 45 (37, 53) | 0.11 |

All 20 CPGs for the febrile young infant 28 days of age recommended urine, blood, CSF testing, and hospitalization for all infants (Figure 1). Of the 16 hospitals with CPGs for febrile infants aged 29 to 56 days, all recommended urine and blood testing for all patients, except for 1 CPG, which recommended consideration of blood testing but not to obtain routinely. Hospitals varied in recommendations for CSF testing among infants aged 29 to 56 days: 8 (50%) recommended CSF testing in all patients and 8 (50%) recommended CSF testing only if the patient was high risk per defined criteria (based on history, physical examination, urine, and blood testing). In all 16 CPGs, hospitalization was recommended only for high‐risk infants. For low‐risk infants aged 2956 days being discharged from the ED, 3 hospitals recommended ceftriaxone for all, 9 recommended consideration of ceftriaxone, and 4 recommended against antibiotics (Figure 1).

Study Patients

During the study period, there were 10,415 infants 56 days old with a diagnosis of fever at the 33 participating hospitals. After exclusion of 635 (6.1%) infants with a complex chronic condition and 445 (4.3%) transferred from another institution (including 42 with a complex chronic condition), 9377 infants remained in our study cohort. Approximately one‐third of the cohort was 28 days of age and two‐thirds aged 29 to 56 days. The overall SBI rate was 8.5% but varied by age (11.9% in infants 28 days and 6.9% in infants 29 to 56 days of age) (Table 1).

CPGs and Use of Diagnostic Testing, Hospitalization Rates, Ceftriaxone Use, and Revisits for SBI

For infants 28 days of age, the presence of a CPG was not associated with urine, blood, CSF testing, or hospitalization after multivariable adjustment (Table 2). Among infants aged 29 to 56 days, urine testing did not differ based on the presence of a CPG, whereas blood testing was performed less often at the 1 hospital whose CPG recommended to consider, but not routinely obtain, testing (aOR: 0.4, 95% CI: 0.3‐0.7, P=0.001). Compared to hospitals without a CPG, CSF testing was performed less often at hospitals with CPG recommendations to only obtain CSF if high risk (aOR: 0.5, 95% CI: 0.3‐0.8, P=0.002). However, the odds of hospitalization did not differ at institutions with and without a febrile infant CPG (aOR: 0.7, 95% CI: 0.5‐1.1, P=0.10). For infants aged 29 to 56 days discharged from the ED, ceftriaxone was administered more often at hospitals with CPGs that recommended ceftriaxone for all discharged patients (aOR: 4.6, 95% CI: 2.39.3, P<0.001) and less often at hospitals whose CPGs recommended against antibiotics (aOR: 0.3, 95% CI: 0.1‐0.9, P=0.03) (Table 3). Our findings were similar in the subgroup of infants without bronchiolitis or prematurity (see Supporting Tables 1 and 2 in the online version of this article). After exclusion of hospitals with a CPG implemented during the 2013 calendar year (4 hospitals excluded in the 28 days age group and 2 hospitals excluded in the 29 to 56 days age group), infants aged 29 to 56 days cared for at a hospital with a CPG experienced a lower odds of hospitalization (aOR: 0.7, 95% CI: 0.4‐0.98, P=0.04). Otherwise, our findings in both age groups did not materially differ from the main analyses.

| Testing/Hospitalization | No. of Hospitals | No. of Patients | % Received* | aOR (95% CI) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| Laboratory testing | |||||

| Urine testing | |||||

| No CPG | 13 | 996 | 75.6 | Ref | |

| CPG: recommend for all | 20 | 2,149 | 80.7 | 1.2 (0.9‐1.7) | 0.22 |

| Blood testing | |||||

| No CPG | 13 | 996 | 76.9 | Ref | |

| CPG: recommend for all | 20 | 2,149 | 81.8 | 1.2 (0.9‐1.7) | 0.25 |

| CSF testing‖ | |||||

| No CPG | 13 | 996 | 71.0 | Ref | |

| CPG: recommend for all | 20 | 2,149 | 77.5 | 1.3 (1.01.7) | 0.08 |

| Disposition | |||||

| Hospitalization | |||||

| No CPG | 13 | 996 | 75.4 | Ref | |

| CPG: recommend for all | 20 | 2,149 | 81.6 | 1.2 (0.9‐1.8) | 0.26 |

| Testing/Hospitalization | No. of Hospitals | No. of Patients | % Received* | aOR (95% CI) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| Laboratory resting | |||||

| Urine testing | |||||

| No CPG | 17 | 2,460 | 81.1 | Ref | |

| CPG: recommend for all | 16 | 3,772 | 82.1 | 0.9 (0.7‐1.4) | 0.76 |

| Blood testing | |||||

| No CPG | 17 | 2,460 | 79.4 | Ref | |

| CPG: recommend for all | 15 | 3,628 | 82.6 | 1.1 (0.7‐1.6) | 0.70 |

| CPG: recommend consider | 1 | 144 | 62.5 | 0.4 (0.3‐0.7) | 0.001 |

| CSF testing‖ | |||||

| No CPG | 17 | 2,460 | 46.3 | Ref | |

| CPG: recommend for all | 8 | 1,517 | 70.3 | 1.3 (0.9‐1.9) | 0.11 |

| CPG: recommend if high‐risk | 8 | 2,255 | 39.9 | 0.5 (0.3‐0.8) | 0.002 |

| Disposition | |||||

| Hospitalization | |||||

| No CPG | 17 | 2,460 | 47.0 | Ref | |

| CPG: recommend if high‐risk | 16 | 3,772 | 42.0 | 0.7 (0.5‐1.1) | 0.10 |

| Ceftriaxone if discharged | |||||

| No CPG | 17 | 1,304 | 11.7 | Ref | |

| CPG: recommend against | 4 | 313 | 10.9 | 0.3 (0.1‐0.9) | 0.03 |

| CPG: recommend consider | 9 | 1,567 | 14.4 | 1.5 (0.9‐2.4) | 0.09 |

| CPG: recommend for all | 3 | 306 | 64.1 | 4.6 (2.39.3) | < 0.001 |

Three‐day revisits for SBI were similarly low at hospitals with and without CPGs among infants 28 days (1.5% vs 0.8%, P=0.44) and 29 to 56 days of age (1.4% vs 1.1%, P=0.44) and did not differ after exclusion of hospitals with a CPG implemented in 2013.

CPGs and Costs

Among infants 28 days of age, costs per visit did not differ for admitted and discharged patients based on CPG presence. The presence of an ED febrile infant CPG was associated with higher costs for both admitted and discharged infants 29 to 56 days of age (Table 4). The cost analysis did not significantly differ after exclusion of hospitals with CPGs implemented in 2013.

| 28 Days, Cost, Median (IQR) | 29 to 56 Days, Cost, Median (IQR) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No CPG | CPG | P Value | No CPG | CPG | P Value | |

| ||||||

| Admitted | $4,979 ($3,408$6,607) [n=751] | $4,715 ($3,472$6,526) [n=1,753] | 0.79 | $3,756 ($2,725$5,041) [n=1,156] | $3,923 ($3,077$5,243) [n=1,586] | <0.001 |

| Discharged | $298 ($166$510) [n=245] | $231 ($160$464) [n=396] | 0.10 | $681($398$982) [n=1,304)] | $764 ($412$1,100) [n=2,186] | <0.001 |

DISCUSSION

We described the content and association of CPGs with management of the febrile infant 56 days of age across a large sample of children's hospitals. Nearly two‐thirds of included pediatric EDs have a CPG for the management of young febrile infants. Management of febrile infants 28 days was uniform, with a majority hospitalized after urine, blood, and CSF testing regardless of the presence of a CPG. In contrast, CPGs for infants 29 to 56 days of age varied in their recommendations for CSF testing as well as ceftriaxone use for infants discharged from the ED. Consequently, we observed considerable hospital variability in CSF testing and ceftriaxone use for discharged infants, which correlates with variation in the presence and content of CPGs. Institutional CPGs may be a source of the across‐hospital variation in care of febrile young infants observed in prior study.[9]

Febrile infants 28 days of age are at particularly high risk for SBI, with a prevalence of nearly 20% or higher.[2, 3, 29] The high prevalence of SBI, combined with the inherent difficulty in distinguishing neonates with and without SBI,[2, 30] has resulted in uniform CPG recommendations to perform the full‐sepsis workup in this young age group. Similar to prior studies,[8, 9] we observed that most febrile infants 28 days undergo the full sepsis evaluation, including CSF testing, and are hospitalized regardless of the presence of a CPG.

However, given the conflicting recommendations for febrile infants 29 to 56 days of age,[4, 5, 6] the optimal management strategy is less certain.[7] The Rochester, Philadelphia, and Boston criteria, 3 published models to identify infants at low risk for SBI, primarily differ in their recommendations for CSF testing and ceftriaxone use in this age group.[4, 5, 6] Half of the CPGs recommended CSF testing for all febrile infants, and half recommended CSF testing only if the infant was high risk. Institutional guidelines that recommended selective CSF testing for febrile infants aged 29 to 56 days were associated with lower rates of CSF testing. Furthermore, ceftriaxone use varied based on CPG recommendations for low‐risk infants discharged from the ED. Therefore, the influence of febrile infant CPGs mainly relates to the limiting of CSF testing and targeted ceftriaxone use in low‐risk infants. As the rate of return visits for SBI is low across hospitals, future study should assess outcomes at hospitals with CPGs recommending selective CSF testing. Of note, infants 29 to 56 days of age were less likely to be hospitalized when cared for at a hospital with an established CPG prior to 2013 without increase in 3‐day revisits for SBI. This finding may indicate that longer duration of CPG implementation is associated with lower rates of hospitalization for low‐risk infants; this finding merits further study.

The presence of a CPG was not associated with lower costs for febrile infants in either age group. Although individual healthcare systems have achieved lower costs with CPG implementation,[12] the mere presence of a CPG is not associated with lower costs when assessed across institutions. Higher costs for admitted and discharged infants 29 to 56 days of age in the presence of a CPG likely reflects the higher rate of CSF testing at hospitals whose CPGs recommend testing for all febrile infants, as well as inpatient management strategies for hospitalized infants not captured in our study. Future investigation should include an assessment of the cost‐effectiveness of the various testing and treatment strategies employed for the febrile young infant.

Our study has several limitations. First, the validity of ICD‐9 diagnosis codes for identifying young infants with fever is not well established, and thus our study is subject to misclassification bias. To minimize missed patients, we included infants with either an ICD‐9 admission or discharge diagnosis of fever; however, utilization of diagnosis codes for patient identification may have resulted in undercapture of infants with a measured temperature of 38.0C. It is also possible that some patients who did not undergo testing were misclassified as having a fever or had temperatures below standard thresholds to prompt diagnostic testing. This is a potential reason that testing was not performed in 100% of infants, even at hospitals with CPGs that recommended testing for all patients. Additionally, some febrile infants diagnosed with SBI may not have an associated ICD‐9 diagnosis code for fever. Although the overall SBI rate observed in our study was similar to prior studies,[4, 31] the rate in neonates 28 days of age was lower than reported in recent investigations,[2, 3] which may indicate inclusion of a higher proportion of low‐risk febrile infants. With the exception of bronchiolitis, we also did not assess diagnostic testing in the presence of other identified sources of infection such as herpes simplex virus.

Second, we were unable to assess the presence or absence of a CPG at the 4 excluded EDs that did not respond to the survey or the institutions excluded for data‐quality issues. However, included and excluded hospitals did not differ in region or annual ED volume (data not shown).

Third, although we classified hospitals based upon the presence and content of CPGs, we were unable to fully evaluate adherence to the CPG at each site.

Last, though PHIS hospitals represent 85% of freestanding children's hospitals, many febrile infants are hospitalized at non‐PHIS institutions; our results may not be generalizable to care provided at nonchildren's hospitals.

CONCLUSIONS

Management of febrile neonates 28 days of age does not vary based on CPG presence. However, CPGs for the febrile infant aged 29 to 56 days vary in recommendations for CSF testing as well as ceftriaxone use for low‐risk patients, which significantly contributes to practice variation and healthcare costs across institutions.

Acknowledgements

The Febrile Young Infant Research Collaborative includes the following additional investigators who are acknowledged for their work on this study: Kao‐Ping Chua, MD, Harvard PhD Program in Health Policy, Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts, and Division of Emergency Medicine, Department of Pediatrics, Boston Children's Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts; Elana A. Feldman, BA, University of Washington School of Medicine, Seattle, Washington; and Katie L. Hayes, BS, Division of Emergency Medicine, Department of Pediatrics, The Children's Hospital of Philadelphia, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Disclosures

This project was funded in part by The Gerber Foundation Novice Researcher Award (Ref #18273835). Dr. Fran Balamuth received career development support from the National Institutes of Health (NHLBI K12‐HL109009). Funders were not involved in design or conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, or interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript. The authors have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose. No payment was received for the production of this article. The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to this article to disclose.

- , , . Performance of low‐risk criteria in the evaluation of young infants with fever: review of the literature. Pediatrics. 2010;125:228–233.

- , , , , , . A week‐by‐week analysis of the low‐risk criteria for serious bacterial infection in febrile neonates. Arch Dis Child. 2009;94:287–292.

- , , , et al. Is 15 days an appropriate cut‐off age for considering serious bacterial infection in the management of febrile infants? Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2012;31:455–458.

- , , . Outpatient management without antibiotics of fever in selected infants. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:1437–1441.

- , , . Identifying febrile infants at risk for a serious bacterial infection. J Pediatr. 1993;123:489–490.

- , , , et al. Febrile infants at low risk for serious bacterial infection—an appraisal of the Rochester criteria and implications for management. Febrile Infant Collaborative Study Group. Pediatrics. 1994;94:390–396.

- American College of Emergency Physicians Clinical Policies Committee; American College of Emergency Physicians Clinical Policies Subcommittee on Pediatric Fever. Clinical policy for children younger than three years presenting to the emergency department with fever. Ann Emerg Med. 2003;42:530–545.

- , , , et al. Management of febrile neonates in US pediatric emergency departments. Pediatrics. 2014;133:187–195.

- , , , et al. Variation in care of the febrile young infant <90 days in US pediatric emergency departments. Pediatrics. 2014;134:667–677.

- , , , , . Fever survey highlights significant variations in how infants aged ≤60 days are evaluated and underline the need for guidelines. Acta Paediatr. 2014;103:379–385.

- . Evidence‐based guidelines and critical pathways for quality improvement. Pediatrics. 1999;103:225–232.

- , , , et al. Costs and infant outcomes after implementation of a care process model for febrile infants. Pediatrics. 2012;130:e16–e24.

- , , , , , . Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata‐driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42:377–381.

- , , , , , . Variation in occult injury screening for children with suspected abuse in selected US children's hospitals. Pediatrics. 2012;130:853–860.

- . Achieving data quality. How data from a pediatric health information system earns the trust of its users. J AHIMA. 2004;75:22–26.

- , , , . Corticosteroids and mortality in children with bacterial meningitis. JAMA. 2008;299:2048–2055.

- , , , et al. Variation in resource utilization across a national sample of pediatric emergency departments. J Pediatr. 2013;163:230–236.

- , , , , , . Deaths attributed to pediatric complex chronic conditions: national trends and implications for supportive care services. Pediatrics. 2001;107:E99.

- US Census Bureau. Geographic terms and concepts—census divisions and census regions. Available at: https://www.census.gov/geo/reference/gtc/gtc_census_divreg.html. Accessed September 10, 2014.

- , , , et al. Pediatric observation status: are we overlooking a growing population in children's hospitals? J Hosp Med. 2012;7:530–536.

- , , , et al. Differences in designations of observation care in US freestanding children's hospitals: are they virtual or real? J Hosp Med. 2012;7:287–293.

- , , , et al. Accuracy of administrative billing codes to detect urinary tract infection hospitalizations. Pediatrics. 2011;128:323–330.

- , , , et al. Identifying pediatric community‐acquired pneumonia hospitalizations: accuracy of administrative billing codes. JAMA Pediatr. 2013;167:851–858.

- , , , . Initial emergency department diagnosis and return visits: risk versus perception. Ann Emerg Med. 1998;32:569–573.

- , , , , . A national depiction of children with return visits to the emergency department within 72 hours, 2001–2007. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2012;28:606–610.

- Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project. Cost‐to‐charge ratio files. Available at: http://www.hcup‐us.ahrq.gov/db/state/costtocharge.jsp. Accessed September 11, 2014.

- , , , et al. Risk of serious bacterial infection in young febrile infants with respiratory syncytial virus infections. Pediatrics. 2004;113:1728–1734.

- , , , et al. Establishing benchmarks for the hospitalized care of children with asthma, bronchiolitis, and pneumonia. Pediatrics. 2014;134:555–562.

- , , , , , . Well appearing young infants with fever without known source in the emergency department: are lumbar punctures always necessary? Eur J Emerg Med. 2010;17:167–169.

- , . Unpredictability of serious bacterial illness in febrile infants from birth to 1 month of age. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1999;153:508–511.

- , , , et al. Management and outcomes of care of fever in early infancy. JAMA. 2004;291:1203–1212.

Febrile young infants are at high risk for serious bacterial infection (SBI) with reported rates of 8.5% to 12%, even higher in neonates 28 days of age.[1, 2, 3] As a result, febrile infants often undergo extensive diagnostic evaluation consisting of a combination of urine, blood, and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) testing.[4, 5, 6] Several clinical prediction algorithms use this diagnostic testing to identify febrile infants at low risk for SBI, but they differ with respect to age range, recommended testing, antibiotic administration, and threshold for hospitalization.[4, 5, 6] Additionally, the optimal management strategy for this population has not been defined.[7] Consequently, laboratory testing, antibiotic use, and hospitalization for febrile young infants vary widely among hospitals.[8, 9, 10]

Clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) are designed to implement evidence‐based care and reduce practice variability, with the goal of improving quality of care and optimizing costs.[11] Implementation of a CPG for management of febrile young infants in the Intermountain Healthcare System was associated with greater adherence to evidence‐based care and lower costs.[12] However, when strong evidence is lacking, different interpretations of febrile infant risk classification incorporated into local CPGs may be a major driver of the across‐hospital practice variation observed in prior studies.[8, 9] Understanding sources of variability as well as determining the association of CPGs with clinicians' practice patterns can help identify quality improvement opportunities, either through national benchmarking or local efforts.

Our primary objectives were to compare (1) recommendations of pediatric emergency departmentbased institutional CPGs for febrile young infants and (2) rates of urine, blood, CSF testing, hospitalization, and ceftriaxone use at emergency department (ED) discharge based upon CPG presence and the specific CPG recommendations. Our secondary objectives were to describe the association of CPGs with healthcare costs and return visits for SBI.

METHODS

Study Design

We used the Pediatric Health Information System (PHIS) to identify febrile infants 56 days of age who presented to the ED between January 1, 2013 and December 31, 2013. We also surveyed ED providers at participating PHIS hospitals. Informed consent was obtained from survey respondents. The institutional review board at Boston Children's Hospital approved the study protocol.

Clinical Practice Guideline Survey

We sent an electronic survey to medical directors or division directors at 37 pediatric EDs to determine whether their ED utilized a CPG for the management of the febrile young infant in 2013. If no response was received after the second attempt, we queried ED fellowship directors or other ED attending physicians at nonresponding hospitals. Survey items included the presence of a febrile young infant CPG, and if present, the year of implementation, ages targeted, and CPG content. As applicable, respondents were asked to share their CPG and/or provide the specific CPG recommendations.

We collected and managed survey data using the Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) electronic data capture tools hosted at Boston Children's Hospital. REDCap is a secure, Web‐based application designed to support data capture for research studies.[13]

Data Source

The PHIS database contains administrative data from 44 US children's hospitals. These hospitals, affiliated with the Children's Hospital Association, represent 85% of freestanding US children's hospitals.[14] Encrypted patient identifiers permit tracking of patients across encounters.[15] Data quality and integrity are assured jointly by the Children's Hospital Association and participating hospitals.[16] For this study, 7 hospitals were excluded due to incomplete ED data or known data‐quality issues.[17]

Patients

We identified study infants using the following International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision (ICD‐9) admission or discharge diagnosis codes for fever as defined previously[8, 9]: 780.6, 778.4, 780.60, or 780.61. We excluded infants with a complex chronic condition[18] and those transferred from another institution, as these infants may warrant a nonstandard evaluation and/or may have incomplete data. For infants with >1 ED visit for fever during the study period, repeat visits within 3 days of an index visit were considered a revisit for the same episode of illness; visits >3 days following an index visit were considered as a new index visit.

Study Definitions

From the PHIS database, we abstracted demographic characteristics (gender, race/ethnicity), insurance status, and region where the hospital was located (using US Census categories[19]). Billing codes were used to assess whether urine, blood, and CSF testing (as defined previously[9]) were performed during the ED evaluation. To account for ED visits that spanned the midnight hour, for hospitalized patients we considered any testing or treatment occurring on the initial or second hospital day to be performed in the ED; billing code data in PHIS are based upon calendar day and do not distinguish testing performed in the ED versus inpatient setting.[8, 9] Patients billed for observation care were classified as being hospitalized.[20, 21]

We identified the presence of an SBI using ICD‐9 diagnosis codes for the following infections as described previously[9]: urinary tract infection or pyelonephritis,[22] bacteremia or sepsis, bacterial meningitis,[16] pneumonia,[23] or bacterial enteritis. To assess return visits for SBI that required inpatient management, we defined an ED revisit for an SBI as a return visit within 3 days of ED discharge[24, 25] that resulted in hospitalization with an associated ICD‐9 discharge diagnosis code for an SBI.

Hospitals charges in PHIS database were adjusted for hospital location by using the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services price/wage index. Costs were estimated by applying hospital‐level cost‐to‐charge ratios to charge data.[26]

Measured Exposures

The primary exposure was the presence of an ED‐based CPG for management of the febrile young infant aged 28 days and 29 to 56 days; 56 days was used as the upper age limit as all of the CPGs included infants up to this age or beyond. Six institutions utilized CPGs with different thresholds to define the age categories (eg, dichotomized at 27 or 30 days); these CPGs were classified into the aforementioned age groups to permit comparisons across standardized age groups. We classified institutions based on the presence of a CPG. To assess differences in the application of low‐risk criteria, the CPGs were further classified a priori based upon specific recommendations around laboratory testing and hospitalization, as well as ceftriaxone use for infants aged 29 to 56 days discharged from the ED. CPGs were categorized based upon whether testing, hospitalization, and ceftriaxone use were: (1) recommended for all patients, (2) recommended only if patients were classified as high risk (absence of low‐risk criteria), (3) recommended against, or (4) recommended to consider at clinician discretion.

Outcome Measures

Measured outcomes were performance of urine, blood, CSF testing, and hospitalization rate, as well as rate of ceftriaxone use for discharged infants aged 29 to 56 days, 3‐day revisits for SBI, and costs per visit, which included hospitalization costs for admitted patients.

Data Analysis

We described continuous variables using median and interquartile range or range values and categorical variables using frequencies. We compared medians using Wilcoxon rank sum and categorical variables using a [2] test. We compared rates of testing, hospitalization, ceftriaxone use, and 3‐day revisits for SBI based on the presence of a CPG, and when present, the specific CPG recommendations. Costs per visit were compared between institutions with and without CPGs and assessed separately for admitted and discharged patients. To adjust for potential confounders and clustering of patients within hospitals, we used generalized estimating equations with logistic regression to generate adjusted odd ratios (aORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Models were adjusted for geographic region, payer, race, and gender. Statistical analyses were performed by using SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). We determined statistical significance as a 2‐tailed P value <0.05.

Febrile infants with bronchiolitis or a history of prematurity may be managed differently from full‐term febrile young infants without bronchiolitis.[6, 27] Therefore, we performed a subgroup analysis after exclusion of infants with an ICD‐9 discharge diagnosis code for bronchiolitis (466.11 and 466.19)[28] or prematurity (765).

Because our study included ED encounters in 2013, we repeated our analyses after exclusion of hospitals with CPGs implemented during the 2013 calendar year.

RESULTS

CPG by Institution

Thirty‐three (89.2%) of the 37 EDs surveyed completed the questionnaire. Overall, 21 (63.6%) of the 33 EDs had a CPG; 15 (45.5%) had a CPG for all infants 56 days of age, 5 (15.2%) had a CPG for infants 28 days only, and 1 (3.0%) had a CPG for infants 29 to 56 days but not 28 days of age (Figure 1). Seventeen EDs had an established CPG prior to 2013, and 4 hospitals implemented a CPG during the 2013 calendar year, 2 with CPGs for neonates 28 days and 2 with CPGs for both 28 days and 29 to 56 days of age. Hospitals with CPGs were more likely to be located in the Northeast and West regions of the United States and provide care to a higher proportion of non‐Hispanic white patients, as well as those with commercial insurance (Table 1).

| Characteristic | 28 Days | 2956 Days | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No CPG, n=996, N (%) | CPG, n=2,149, N (%) | P Value | No CPG, n=2,460, N (%) | CPG, n=3,772, N (%) | P Value | |

| ||||||

| Race | ||||||

| Non‐Hispanic white | 325 (32.6) | 996 (46.3) | 867 (35.2) | 1,728 (45.8) | ||

| Non‐Hispanic black | 248 (24.9) | 381 (17.7) | 593 (24.1) | 670 (17.8) | ||

| Hispanic | 243 (24.4) | 531 (24.7) | 655 (26.6) | 986 (26.1) | ||

| Asian | 28 (2.8) | 78 (3.6) | 40 (1.6) | 122 (3.2) | ||

| Other Race | 152 (15.3) | 163 (7.6) | <0.001 | 305 (12.4) | 266 (7.1) | <0.001 |

| Gender | ||||||

| Female | 435 (43.7) | 926 (43.1) | 0.76 | 1,067 (43.4) | 1,714 (45.4) | 0.22 |

| Payer | ||||||

| Commercial | 243 (24.4) | 738 (34.3) | 554 (22.5) | 1,202 (31.9) | ||

| Government | 664 (66.7) | 1,269 (59.1) | 1,798 (73.1) | 2,342 (62.1) | ||

| Other payer | 89 (8.9) | 142 (6.6) | <0.001 | 108 (4.4) | 228 (6.0) | <0.001 |

| Region | ||||||

| Northeast | 39 (3.9) | 245 (11.4) | 77 (3.1) | 572 (15.2) | ||

| South | 648 (65.1) | 915 (42.6) | 1,662 (67.6) | 1,462 (38.8) | ||

| Midwest | 271 (27.2) | 462 (21.5) | 506 (20.6) | 851 (22.6) | ||

| West | 38 (3.8) | 527 (24.5) | <0.001 | 215 (8.7) | 887 (23.5) | <0.001 |

| Serious bacterial infection | ||||||

| Overall* | 131 (13.2) | 242 (11.3) | 0.14 | 191 (7.8) | 237 (6.3) | 0.03 |

| UTI/pyelonephritis | 73 (7.3) | 153 (7.1) | 103 (4.2) | 154 (4.1) | ||

| Bacteremia/sepsis | 56 (5.6) | 91 (4.2) | 78 (3.2) | 61 (1.6) | ||

| Bacterial meningitis | 15 (1.5) | 15 (0.7) | 4 (0.2) | 14 (0.4) | ||

| Age, d, median (IQR) | 18 (11, 24) | 18 (11, 23) | 0.67 | 46 (37, 53) | 45 (37, 53) | 0.11 |

All 20 CPGs for the febrile young infant 28 days of age recommended urine, blood, CSF testing, and hospitalization for all infants (Figure 1). Of the 16 hospitals with CPGs for febrile infants aged 29 to 56 days, all recommended urine and blood testing for all patients, except for 1 CPG, which recommended consideration of blood testing but not to obtain routinely. Hospitals varied in recommendations for CSF testing among infants aged 29 to 56 days: 8 (50%) recommended CSF testing in all patients and 8 (50%) recommended CSF testing only if the patient was high risk per defined criteria (based on history, physical examination, urine, and blood testing). In all 16 CPGs, hospitalization was recommended only for high‐risk infants. For low‐risk infants aged 2956 days being discharged from the ED, 3 hospitals recommended ceftriaxone for all, 9 recommended consideration of ceftriaxone, and 4 recommended against antibiotics (Figure 1).

Study Patients

During the study period, there were 10,415 infants 56 days old with a diagnosis of fever at the 33 participating hospitals. After exclusion of 635 (6.1%) infants with a complex chronic condition and 445 (4.3%) transferred from another institution (including 42 with a complex chronic condition), 9377 infants remained in our study cohort. Approximately one‐third of the cohort was 28 days of age and two‐thirds aged 29 to 56 days. The overall SBI rate was 8.5% but varied by age (11.9% in infants 28 days and 6.9% in infants 29 to 56 days of age) (Table 1).

CPGs and Use of Diagnostic Testing, Hospitalization Rates, Ceftriaxone Use, and Revisits for SBI

For infants 28 days of age, the presence of a CPG was not associated with urine, blood, CSF testing, or hospitalization after multivariable adjustment (Table 2). Among infants aged 29 to 56 days, urine testing did not differ based on the presence of a CPG, whereas blood testing was performed less often at the 1 hospital whose CPG recommended to consider, but not routinely obtain, testing (aOR: 0.4, 95% CI: 0.3‐0.7, P=0.001). Compared to hospitals without a CPG, CSF testing was performed less often at hospitals with CPG recommendations to only obtain CSF if high risk (aOR: 0.5, 95% CI: 0.3‐0.8, P=0.002). However, the odds of hospitalization did not differ at institutions with and without a febrile infant CPG (aOR: 0.7, 95% CI: 0.5‐1.1, P=0.10). For infants aged 29 to 56 days discharged from the ED, ceftriaxone was administered more often at hospitals with CPGs that recommended ceftriaxone for all discharged patients (aOR: 4.6, 95% CI: 2.39.3, P<0.001) and less often at hospitals whose CPGs recommended against antibiotics (aOR: 0.3, 95% CI: 0.1‐0.9, P=0.03) (Table 3). Our findings were similar in the subgroup of infants without bronchiolitis or prematurity (see Supporting Tables 1 and 2 in the online version of this article). After exclusion of hospitals with a CPG implemented during the 2013 calendar year (4 hospitals excluded in the 28 days age group and 2 hospitals excluded in the 29 to 56 days age group), infants aged 29 to 56 days cared for at a hospital with a CPG experienced a lower odds of hospitalization (aOR: 0.7, 95% CI: 0.4‐0.98, P=0.04). Otherwise, our findings in both age groups did not materially differ from the main analyses.

| Testing/Hospitalization | No. of Hospitals | No. of Patients | % Received* | aOR (95% CI) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| Laboratory testing | |||||

| Urine testing | |||||

| No CPG | 13 | 996 | 75.6 | Ref | |

| CPG: recommend for all | 20 | 2,149 | 80.7 | 1.2 (0.9‐1.7) | 0.22 |

| Blood testing | |||||

| No CPG | 13 | 996 | 76.9 | Ref | |

| CPG: recommend for all | 20 | 2,149 | 81.8 | 1.2 (0.9‐1.7) | 0.25 |

| CSF testing‖ | |||||

| No CPG | 13 | 996 | 71.0 | Ref | |

| CPG: recommend for all | 20 | 2,149 | 77.5 | 1.3 (1.01.7) | 0.08 |

| Disposition | |||||

| Hospitalization | |||||

| No CPG | 13 | 996 | 75.4 | Ref | |

| CPG: recommend for all | 20 | 2,149 | 81.6 | 1.2 (0.9‐1.8) | 0.26 |

| Testing/Hospitalization | No. of Hospitals | No. of Patients | % Received* | aOR (95% CI) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| Laboratory resting | |||||

| Urine testing | |||||

| No CPG | 17 | 2,460 | 81.1 | Ref | |

| CPG: recommend for all | 16 | 3,772 | 82.1 | 0.9 (0.7‐1.4) | 0.76 |

| Blood testing | |||||

| No CPG | 17 | 2,460 | 79.4 | Ref | |

| CPG: recommend for all | 15 | 3,628 | 82.6 | 1.1 (0.7‐1.6) | 0.70 |

| CPG: recommend consider | 1 | 144 | 62.5 | 0.4 (0.3‐0.7) | 0.001 |

| CSF testing‖ | |||||

| No CPG | 17 | 2,460 | 46.3 | Ref | |

| CPG: recommend for all | 8 | 1,517 | 70.3 | 1.3 (0.9‐1.9) | 0.11 |

| CPG: recommend if high‐risk | 8 | 2,255 | 39.9 | 0.5 (0.3‐0.8) | 0.002 |

| Disposition | |||||

| Hospitalization | |||||

| No CPG | 17 | 2,460 | 47.0 | Ref | |

| CPG: recommend if high‐risk | 16 | 3,772 | 42.0 | 0.7 (0.5‐1.1) | 0.10 |

| Ceftriaxone if discharged | |||||

| No CPG | 17 | 1,304 | 11.7 | Ref | |

| CPG: recommend against | 4 | 313 | 10.9 | 0.3 (0.1‐0.9) | 0.03 |

| CPG: recommend consider | 9 | 1,567 | 14.4 | 1.5 (0.9‐2.4) | 0.09 |

| CPG: recommend for all | 3 | 306 | 64.1 | 4.6 (2.39.3) | < 0.001 |

Three‐day revisits for SBI were similarly low at hospitals with and without CPGs among infants 28 days (1.5% vs 0.8%, P=0.44) and 29 to 56 days of age (1.4% vs 1.1%, P=0.44) and did not differ after exclusion of hospitals with a CPG implemented in 2013.

CPGs and Costs

Among infants 28 days of age, costs per visit did not differ for admitted and discharged patients based on CPG presence. The presence of an ED febrile infant CPG was associated with higher costs for both admitted and discharged infants 29 to 56 days of age (Table 4). The cost analysis did not significantly differ after exclusion of hospitals with CPGs implemented in 2013.

| 28 Days, Cost, Median (IQR) | 29 to 56 Days, Cost, Median (IQR) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No CPG | CPG | P Value | No CPG | CPG | P Value | |

| ||||||

| Admitted | $4,979 ($3,408$6,607) [n=751] | $4,715 ($3,472$6,526) [n=1,753] | 0.79 | $3,756 ($2,725$5,041) [n=1,156] | $3,923 ($3,077$5,243) [n=1,586] | <0.001 |

| Discharged | $298 ($166$510) [n=245] | $231 ($160$464) [n=396] | 0.10 | $681($398$982) [n=1,304)] | $764 ($412$1,100) [n=2,186] | <0.001 |

DISCUSSION

We described the content and association of CPGs with management of the febrile infant 56 days of age across a large sample of children's hospitals. Nearly two‐thirds of included pediatric EDs have a CPG for the management of young febrile infants. Management of febrile infants 28 days was uniform, with a majority hospitalized after urine, blood, and CSF testing regardless of the presence of a CPG. In contrast, CPGs for infants 29 to 56 days of age varied in their recommendations for CSF testing as well as ceftriaxone use for infants discharged from the ED. Consequently, we observed considerable hospital variability in CSF testing and ceftriaxone use for discharged infants, which correlates with variation in the presence and content of CPGs. Institutional CPGs may be a source of the across‐hospital variation in care of febrile young infants observed in prior study.[9]

Febrile infants 28 days of age are at particularly high risk for SBI, with a prevalence of nearly 20% or higher.[2, 3, 29] The high prevalence of SBI, combined with the inherent difficulty in distinguishing neonates with and without SBI,[2, 30] has resulted in uniform CPG recommendations to perform the full‐sepsis workup in this young age group. Similar to prior studies,[8, 9] we observed that most febrile infants 28 days undergo the full sepsis evaluation, including CSF testing, and are hospitalized regardless of the presence of a CPG.

However, given the conflicting recommendations for febrile infants 29 to 56 days of age,[4, 5, 6] the optimal management strategy is less certain.[7] The Rochester, Philadelphia, and Boston criteria, 3 published models to identify infants at low risk for SBI, primarily differ in their recommendations for CSF testing and ceftriaxone use in this age group.[4, 5, 6] Half of the CPGs recommended CSF testing for all febrile infants, and half recommended CSF testing only if the infant was high risk. Institutional guidelines that recommended selective CSF testing for febrile infants aged 29 to 56 days were associated with lower rates of CSF testing. Furthermore, ceftriaxone use varied based on CPG recommendations for low‐risk infants discharged from the ED. Therefore, the influence of febrile infant CPGs mainly relates to the limiting of CSF testing and targeted ceftriaxone use in low‐risk infants. As the rate of return visits for SBI is low across hospitals, future study should assess outcomes at hospitals with CPGs recommending selective CSF testing. Of note, infants 29 to 56 days of age were less likely to be hospitalized when cared for at a hospital with an established CPG prior to 2013 without increase in 3‐day revisits for SBI. This finding may indicate that longer duration of CPG implementation is associated with lower rates of hospitalization for low‐risk infants; this finding merits further study.

The presence of a CPG was not associated with lower costs for febrile infants in either age group. Although individual healthcare systems have achieved lower costs with CPG implementation,[12] the mere presence of a CPG is not associated with lower costs when assessed across institutions. Higher costs for admitted and discharged infants 29 to 56 days of age in the presence of a CPG likely reflects the higher rate of CSF testing at hospitals whose CPGs recommend testing for all febrile infants, as well as inpatient management strategies for hospitalized infants not captured in our study. Future investigation should include an assessment of the cost‐effectiveness of the various testing and treatment strategies employed for the febrile young infant.

Our study has several limitations. First, the validity of ICD‐9 diagnosis codes for identifying young infants with fever is not well established, and thus our study is subject to misclassification bias. To minimize missed patients, we included infants with either an ICD‐9 admission or discharge diagnosis of fever; however, utilization of diagnosis codes for patient identification may have resulted in undercapture of infants with a measured temperature of 38.0C. It is also possible that some patients who did not undergo testing were misclassified as having a fever or had temperatures below standard thresholds to prompt diagnostic testing. This is a potential reason that testing was not performed in 100% of infants, even at hospitals with CPGs that recommended testing for all patients. Additionally, some febrile infants diagnosed with SBI may not have an associated ICD‐9 diagnosis code for fever. Although the overall SBI rate observed in our study was similar to prior studies,[4, 31] the rate in neonates 28 days of age was lower than reported in recent investigations,[2, 3] which may indicate inclusion of a higher proportion of low‐risk febrile infants. With the exception of bronchiolitis, we also did not assess diagnostic testing in the presence of other identified sources of infection such as herpes simplex virus.

Second, we were unable to assess the presence or absence of a CPG at the 4 excluded EDs that did not respond to the survey or the institutions excluded for data‐quality issues. However, included and excluded hospitals did not differ in region or annual ED volume (data not shown).

Third, although we classified hospitals based upon the presence and content of CPGs, we were unable to fully evaluate adherence to the CPG at each site.

Last, though PHIS hospitals represent 85% of freestanding children's hospitals, many febrile infants are hospitalized at non‐PHIS institutions; our results may not be generalizable to care provided at nonchildren's hospitals.

CONCLUSIONS

Management of febrile neonates 28 days of age does not vary based on CPG presence. However, CPGs for the febrile infant aged 29 to 56 days vary in recommendations for CSF testing as well as ceftriaxone use for low‐risk patients, which significantly contributes to practice variation and healthcare costs across institutions.

Acknowledgements

The Febrile Young Infant Research Collaborative includes the following additional investigators who are acknowledged for their work on this study: Kao‐Ping Chua, MD, Harvard PhD Program in Health Policy, Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts, and Division of Emergency Medicine, Department of Pediatrics, Boston Children's Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts; Elana A. Feldman, BA, University of Washington School of Medicine, Seattle, Washington; and Katie L. Hayes, BS, Division of Emergency Medicine, Department of Pediatrics, The Children's Hospital of Philadelphia, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Disclosures

This project was funded in part by The Gerber Foundation Novice Researcher Award (Ref #18273835). Dr. Fran Balamuth received career development support from the National Institutes of Health (NHLBI K12‐HL109009). Funders were not involved in design or conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, or interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript. The authors have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose. No payment was received for the production of this article. The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to this article to disclose.

Febrile young infants are at high risk for serious bacterial infection (SBI) with reported rates of 8.5% to 12%, even higher in neonates 28 days of age.[1, 2, 3] As a result, febrile infants often undergo extensive diagnostic evaluation consisting of a combination of urine, blood, and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) testing.[4, 5, 6] Several clinical prediction algorithms use this diagnostic testing to identify febrile infants at low risk for SBI, but they differ with respect to age range, recommended testing, antibiotic administration, and threshold for hospitalization.[4, 5, 6] Additionally, the optimal management strategy for this population has not been defined.[7] Consequently, laboratory testing, antibiotic use, and hospitalization for febrile young infants vary widely among hospitals.[8, 9, 10]

Clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) are designed to implement evidence‐based care and reduce practice variability, with the goal of improving quality of care and optimizing costs.[11] Implementation of a CPG for management of febrile young infants in the Intermountain Healthcare System was associated with greater adherence to evidence‐based care and lower costs.[12] However, when strong evidence is lacking, different interpretations of febrile infant risk classification incorporated into local CPGs may be a major driver of the across‐hospital practice variation observed in prior studies.[8, 9] Understanding sources of variability as well as determining the association of CPGs with clinicians' practice patterns can help identify quality improvement opportunities, either through national benchmarking or local efforts.

Our primary objectives were to compare (1) recommendations of pediatric emergency departmentbased institutional CPGs for febrile young infants and (2) rates of urine, blood, CSF testing, hospitalization, and ceftriaxone use at emergency department (ED) discharge based upon CPG presence and the specific CPG recommendations. Our secondary objectives were to describe the association of CPGs with healthcare costs and return visits for SBI.

METHODS

Study Design

We used the Pediatric Health Information System (PHIS) to identify febrile infants 56 days of age who presented to the ED between January 1, 2013 and December 31, 2013. We also surveyed ED providers at participating PHIS hospitals. Informed consent was obtained from survey respondents. The institutional review board at Boston Children's Hospital approved the study protocol.

Clinical Practice Guideline Survey

We sent an electronic survey to medical directors or division directors at 37 pediatric EDs to determine whether their ED utilized a CPG for the management of the febrile young infant in 2013. If no response was received after the second attempt, we queried ED fellowship directors or other ED attending physicians at nonresponding hospitals. Survey items included the presence of a febrile young infant CPG, and if present, the year of implementation, ages targeted, and CPG content. As applicable, respondents were asked to share their CPG and/or provide the specific CPG recommendations.

We collected and managed survey data using the Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) electronic data capture tools hosted at Boston Children's Hospital. REDCap is a secure, Web‐based application designed to support data capture for research studies.[13]

Data Source

The PHIS database contains administrative data from 44 US children's hospitals. These hospitals, affiliated with the Children's Hospital Association, represent 85% of freestanding US children's hospitals.[14] Encrypted patient identifiers permit tracking of patients across encounters.[15] Data quality and integrity are assured jointly by the Children's Hospital Association and participating hospitals.[16] For this study, 7 hospitals were excluded due to incomplete ED data or known data‐quality issues.[17]

Patients

We identified study infants using the following International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision (ICD‐9) admission or discharge diagnosis codes for fever as defined previously[8, 9]: 780.6, 778.4, 780.60, or 780.61. We excluded infants with a complex chronic condition[18] and those transferred from another institution, as these infants may warrant a nonstandard evaluation and/or may have incomplete data. For infants with >1 ED visit for fever during the study period, repeat visits within 3 days of an index visit were considered a revisit for the same episode of illness; visits >3 days following an index visit were considered as a new index visit.

Study Definitions

From the PHIS database, we abstracted demographic characteristics (gender, race/ethnicity), insurance status, and region where the hospital was located (using US Census categories[19]). Billing codes were used to assess whether urine, blood, and CSF testing (as defined previously[9]) were performed during the ED evaluation. To account for ED visits that spanned the midnight hour, for hospitalized patients we considered any testing or treatment occurring on the initial or second hospital day to be performed in the ED; billing code data in PHIS are based upon calendar day and do not distinguish testing performed in the ED versus inpatient setting.[8, 9] Patients billed for observation care were classified as being hospitalized.[20, 21]

We identified the presence of an SBI using ICD‐9 diagnosis codes for the following infections as described previously[9]: urinary tract infection or pyelonephritis,[22] bacteremia or sepsis, bacterial meningitis,[16] pneumonia,[23] or bacterial enteritis. To assess return visits for SBI that required inpatient management, we defined an ED revisit for an SBI as a return visit within 3 days of ED discharge[24, 25] that resulted in hospitalization with an associated ICD‐9 discharge diagnosis code for an SBI.

Hospitals charges in PHIS database were adjusted for hospital location by using the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services price/wage index. Costs were estimated by applying hospital‐level cost‐to‐charge ratios to charge data.[26]

Measured Exposures

The primary exposure was the presence of an ED‐based CPG for management of the febrile young infant aged 28 days and 29 to 56 days; 56 days was used as the upper age limit as all of the CPGs included infants up to this age or beyond. Six institutions utilized CPGs with different thresholds to define the age categories (eg, dichotomized at 27 or 30 days); these CPGs were classified into the aforementioned age groups to permit comparisons across standardized age groups. We classified institutions based on the presence of a CPG. To assess differences in the application of low‐risk criteria, the CPGs were further classified a priori based upon specific recommendations around laboratory testing and hospitalization, as well as ceftriaxone use for infants aged 29 to 56 days discharged from the ED. CPGs were categorized based upon whether testing, hospitalization, and ceftriaxone use were: (1) recommended for all patients, (2) recommended only if patients were classified as high risk (absence of low‐risk criteria), (3) recommended against, or (4) recommended to consider at clinician discretion.

Outcome Measures

Measured outcomes were performance of urine, blood, CSF testing, and hospitalization rate, as well as rate of ceftriaxone use for discharged infants aged 29 to 56 days, 3‐day revisits for SBI, and costs per visit, which included hospitalization costs for admitted patients.

Data Analysis

We described continuous variables using median and interquartile range or range values and categorical variables using frequencies. We compared medians using Wilcoxon rank sum and categorical variables using a [2] test. We compared rates of testing, hospitalization, ceftriaxone use, and 3‐day revisits for SBI based on the presence of a CPG, and when present, the specific CPG recommendations. Costs per visit were compared between institutions with and without CPGs and assessed separately for admitted and discharged patients. To adjust for potential confounders and clustering of patients within hospitals, we used generalized estimating equations with logistic regression to generate adjusted odd ratios (aORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Models were adjusted for geographic region, payer, race, and gender. Statistical analyses were performed by using SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). We determined statistical significance as a 2‐tailed P value <0.05.

Febrile infants with bronchiolitis or a history of prematurity may be managed differently from full‐term febrile young infants without bronchiolitis.[6, 27] Therefore, we performed a subgroup analysis after exclusion of infants with an ICD‐9 discharge diagnosis code for bronchiolitis (466.11 and 466.19)[28] or prematurity (765).

Because our study included ED encounters in 2013, we repeated our analyses after exclusion of hospitals with CPGs implemented during the 2013 calendar year.

RESULTS

CPG by Institution

Thirty‐three (89.2%) of the 37 EDs surveyed completed the questionnaire. Overall, 21 (63.6%) of the 33 EDs had a CPG; 15 (45.5%) had a CPG for all infants 56 days of age, 5 (15.2%) had a CPG for infants 28 days only, and 1 (3.0%) had a CPG for infants 29 to 56 days but not 28 days of age (Figure 1). Seventeen EDs had an established CPG prior to 2013, and 4 hospitals implemented a CPG during the 2013 calendar year, 2 with CPGs for neonates 28 days and 2 with CPGs for both 28 days and 29 to 56 days of age. Hospitals with CPGs were more likely to be located in the Northeast and West regions of the United States and provide care to a higher proportion of non‐Hispanic white patients, as well as those with commercial insurance (Table 1).

| Characteristic | 28 Days | 2956 Days | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No CPG, n=996, N (%) | CPG, n=2,149, N (%) | P Value | No CPG, n=2,460, N (%) | CPG, n=3,772, N (%) | P Value | |

| ||||||

| Race | ||||||

| Non‐Hispanic white | 325 (32.6) | 996 (46.3) | 867 (35.2) | 1,728 (45.8) | ||

| Non‐Hispanic black | 248 (24.9) | 381 (17.7) | 593 (24.1) | 670 (17.8) | ||

| Hispanic | 243 (24.4) | 531 (24.7) | 655 (26.6) | 986 (26.1) | ||

| Asian | 28 (2.8) | 78 (3.6) | 40 (1.6) | 122 (3.2) | ||

| Other Race | 152 (15.3) | 163 (7.6) | <0.001 | 305 (12.4) | 266 (7.1) | <0.001 |

| Gender | ||||||

| Female | 435 (43.7) | 926 (43.1) | 0.76 | 1,067 (43.4) | 1,714 (45.4) | 0.22 |

| Payer | ||||||

| Commercial | 243 (24.4) | 738 (34.3) | 554 (22.5) | 1,202 (31.9) | ||

| Government | 664 (66.7) | 1,269 (59.1) | 1,798 (73.1) | 2,342 (62.1) | ||

| Other payer | 89 (8.9) | 142 (6.6) | <0.001 | 108 (4.4) | 228 (6.0) | <0.001 |

| Region | ||||||

| Northeast | 39 (3.9) | 245 (11.4) | 77 (3.1) | 572 (15.2) | ||

| South | 648 (65.1) | 915 (42.6) | 1,662 (67.6) | 1,462 (38.8) | ||

| Midwest | 271 (27.2) | 462 (21.5) | 506 (20.6) | 851 (22.6) | ||

| West | 38 (3.8) | 527 (24.5) | <0.001 | 215 (8.7) | 887 (23.5) | <0.001 |

| Serious bacterial infection | ||||||

| Overall* | 131 (13.2) | 242 (11.3) | 0.14 | 191 (7.8) | 237 (6.3) | 0.03 |

| UTI/pyelonephritis | 73 (7.3) | 153 (7.1) | 103 (4.2) | 154 (4.1) | ||

| Bacteremia/sepsis | 56 (5.6) | 91 (4.2) | 78 (3.2) | 61 (1.6) | ||

| Bacterial meningitis | 15 (1.5) | 15 (0.7) | 4 (0.2) | 14 (0.4) | ||

| Age, d, median (IQR) | 18 (11, 24) | 18 (11, 23) | 0.67 | 46 (37, 53) | 45 (37, 53) | 0.11 |

All 20 CPGs for the febrile young infant 28 days of age recommended urine, blood, CSF testing, and hospitalization for all infants (Figure 1). Of the 16 hospitals with CPGs for febrile infants aged 29 to 56 days, all recommended urine and blood testing for all patients, except for 1 CPG, which recommended consideration of blood testing but not to obtain routinely. Hospitals varied in recommendations for CSF testing among infants aged 29 to 56 days: 8 (50%) recommended CSF testing in all patients and 8 (50%) recommended CSF testing only if the patient was high risk per defined criteria (based on history, physical examination, urine, and blood testing). In all 16 CPGs, hospitalization was recommended only for high‐risk infants. For low‐risk infants aged 2956 days being discharged from the ED, 3 hospitals recommended ceftriaxone for all, 9 recommended consideration of ceftriaxone, and 4 recommended against antibiotics (Figure 1).

Study Patients

During the study period, there were 10,415 infants 56 days old with a diagnosis of fever at the 33 participating hospitals. After exclusion of 635 (6.1%) infants with a complex chronic condition and 445 (4.3%) transferred from another institution (including 42 with a complex chronic condition), 9377 infants remained in our study cohort. Approximately one‐third of the cohort was 28 days of age and two‐thirds aged 29 to 56 days. The overall SBI rate was 8.5% but varied by age (11.9% in infants 28 days and 6.9% in infants 29 to 56 days of age) (Table 1).

CPGs and Use of Diagnostic Testing, Hospitalization Rates, Ceftriaxone Use, and Revisits for SBI

For infants 28 days of age, the presence of a CPG was not associated with urine, blood, CSF testing, or hospitalization after multivariable adjustment (Table 2). Among infants aged 29 to 56 days, urine testing did not differ based on the presence of a CPG, whereas blood testing was performed less often at the 1 hospital whose CPG recommended to consider, but not routinely obtain, testing (aOR: 0.4, 95% CI: 0.3‐0.7, P=0.001). Compared to hospitals without a CPG, CSF testing was performed less often at hospitals with CPG recommendations to only obtain CSF if high risk (aOR: 0.5, 95% CI: 0.3‐0.8, P=0.002). However, the odds of hospitalization did not differ at institutions with and without a febrile infant CPG (aOR: 0.7, 95% CI: 0.5‐1.1, P=0.10). For infants aged 29 to 56 days discharged from the ED, ceftriaxone was administered more often at hospitals with CPGs that recommended ceftriaxone for all discharged patients (aOR: 4.6, 95% CI: 2.39.3, P<0.001) and less often at hospitals whose CPGs recommended against antibiotics (aOR: 0.3, 95% CI: 0.1‐0.9, P=0.03) (Table 3). Our findings were similar in the subgroup of infants without bronchiolitis or prematurity (see Supporting Tables 1 and 2 in the online version of this article). After exclusion of hospitals with a CPG implemented during the 2013 calendar year (4 hospitals excluded in the 28 days age group and 2 hospitals excluded in the 29 to 56 days age group), infants aged 29 to 56 days cared for at a hospital with a CPG experienced a lower odds of hospitalization (aOR: 0.7, 95% CI: 0.4‐0.98, P=0.04). Otherwise, our findings in both age groups did not materially differ from the main analyses.

| Testing/Hospitalization | No. of Hospitals | No. of Patients | % Received* | aOR (95% CI) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| Laboratory testing | |||||

| Urine testing | |||||

| No CPG | 13 | 996 | 75.6 | Ref | |

| CPG: recommend for all | 20 | 2,149 | 80.7 | 1.2 (0.9‐1.7) | 0.22 |

| Blood testing | |||||

| No CPG | 13 | 996 | 76.9 | Ref | |

| CPG: recommend for all | 20 | 2,149 | 81.8 | 1.2 (0.9‐1.7) | 0.25 |

| CSF testing‖ | |||||

| No CPG | 13 | 996 | 71.0 | Ref | |

| CPG: recommend for all | 20 | 2,149 | 77.5 | 1.3 (1.01.7) | 0.08 |

| Disposition | |||||

| Hospitalization | |||||

| No CPG | 13 | 996 | 75.4 | Ref | |

| CPG: recommend for all | 20 | 2,149 | 81.6 | 1.2 (0.9‐1.8) | 0.26 |

| Testing/Hospitalization | No. of Hospitals | No. of Patients | % Received* | aOR (95% CI) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| Laboratory resting | |||||

| Urine testing | |||||

| No CPG | 17 | 2,460 | 81.1 | Ref | |

| CPG: recommend for all | 16 | 3,772 | 82.1 | 0.9 (0.7‐1.4) | 0.76 |

| Blood testing | |||||

| No CPG | 17 | 2,460 | 79.4 | Ref | |

| CPG: recommend for all | 15 | 3,628 | 82.6 | 1.1 (0.7‐1.6) | 0.70 |

| CPG: recommend consider | 1 | 144 | 62.5 | 0.4 (0.3‐0.7) | 0.001 |

| CSF testing‖ | |||||

| No CPG | 17 | 2,460 | 46.3 | Ref | |

| CPG: recommend for all | 8 | 1,517 | 70.3 | 1.3 (0.9‐1.9) | 0.11 |

| CPG: recommend if high‐risk | 8 | 2,255 | 39.9 | 0.5 (0.3‐0.8) | 0.002 |

| Disposition | |||||

| Hospitalization | |||||

| No CPG | 17 | 2,460 | 47.0 | Ref | |

| CPG: recommend if high‐risk | 16 | 3,772 | 42.0 | 0.7 (0.5‐1.1) | 0.10 |

| Ceftriaxone if discharged | |||||

| No CPG | 17 | 1,304 | 11.7 | Ref | |

| CPG: recommend against | 4 | 313 | 10.9 | 0.3 (0.1‐0.9) | 0.03 |

| CPG: recommend consider | 9 | 1,567 | 14.4 | 1.5 (0.9‐2.4) | 0.09 |

| CPG: recommend for all | 3 | 306 | 64.1 | 4.6 (2.39.3) | < 0.001 |

Three‐day revisits for SBI were similarly low at hospitals with and without CPGs among infants 28 days (1.5% vs 0.8%, P=0.44) and 29 to 56 days of age (1.4% vs 1.1%, P=0.44) and did not differ after exclusion of hospitals with a CPG implemented in 2013.

CPGs and Costs

Among infants 28 days of age, costs per visit did not differ for admitted and discharged patients based on CPG presence. The presence of an ED febrile infant CPG was associated with higher costs for both admitted and discharged infants 29 to 56 days of age (Table 4). The cost analysis did not significantly differ after exclusion of hospitals with CPGs implemented in 2013.

| 28 Days, Cost, Median (IQR) | 29 to 56 Days, Cost, Median (IQR) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No CPG | CPG | P Value | No CPG | CPG | P Value | |

| ||||||

| Admitted | $4,979 ($3,408$6,607) [n=751] | $4,715 ($3,472$6,526) [n=1,753] | 0.79 | $3,756 ($2,725$5,041) [n=1,156] | $3,923 ($3,077$5,243) [n=1,586] | <0.001 |

| Discharged | $298 ($166$510) [n=245] | $231 ($160$464) [n=396] | 0.10 | $681($398$982) [n=1,304)] | $764 ($412$1,100) [n=2,186] | <0.001 |

DISCUSSION

We described the content and association of CPGs with management of the febrile infant 56 days of age across a large sample of children's hospitals. Nearly two‐thirds of included pediatric EDs have a CPG for the management of young febrile infants. Management of febrile infants 28 days was uniform, with a majority hospitalized after urine, blood, and CSF testing regardless of the presence of a CPG. In contrast, CPGs for infants 29 to 56 days of age varied in their recommendations for CSF testing as well as ceftriaxone use for infants discharged from the ED. Consequently, we observed considerable hospital variability in CSF testing and ceftriaxone use for discharged infants, which correlates with variation in the presence and content of CPGs. Institutional CPGs may be a source of the across‐hospital variation in care of febrile young infants observed in prior study.[9]

Febrile infants 28 days of age are at particularly high risk for SBI, with a prevalence of nearly 20% or higher.[2, 3, 29] The high prevalence of SBI, combined with the inherent difficulty in distinguishing neonates with and without SBI,[2, 30] has resulted in uniform CPG recommendations to perform the full‐sepsis workup in this young age group. Similar to prior studies,[8, 9] we observed that most febrile infants 28 days undergo the full sepsis evaluation, including CSF testing, and are hospitalized regardless of the presence of a CPG.

However, given the conflicting recommendations for febrile infants 29 to 56 days of age,[4, 5, 6] the optimal management strategy is less certain.[7] The Rochester, Philadelphia, and Boston criteria, 3 published models to identify infants at low risk for SBI, primarily differ in their recommendations for CSF testing and ceftriaxone use in this age group.[4, 5, 6] Half of the CPGs recommended CSF testing for all febrile infants, and half recommended CSF testing only if the infant was high risk. Institutional guidelines that recommended selective CSF testing for febrile infants aged 29 to 56 days were associated with lower rates of CSF testing. Furthermore, ceftriaxone use varied based on CPG recommendations for low‐risk infants discharged from the ED. Therefore, the influence of febrile infant CPGs mainly relates to the limiting of CSF testing and targeted ceftriaxone use in low‐risk infants. As the rate of return visits for SBI is low across hospitals, future study should assess outcomes at hospitals with CPGs recommending selective CSF testing. Of note, infants 29 to 56 days of age were less likely to be hospitalized when cared for at a hospital with an established CPG prior to 2013 without increase in 3‐day revisits for SBI. This finding may indicate that longer duration of CPG implementation is associated with lower rates of hospitalization for low‐risk infants; this finding merits further study.

The presence of a CPG was not associated with lower costs for febrile infants in either age group. Although individual healthcare systems have achieved lower costs with CPG implementation,[12] the mere presence of a CPG is not associated with lower costs when assessed across institutions. Higher costs for admitted and discharged infants 29 to 56 days of age in the presence of a CPG likely reflects the higher rate of CSF testing at hospitals whose CPGs recommend testing for all febrile infants, as well as inpatient management strategies for hospitalized infants not captured in our study. Future investigation should include an assessment of the cost‐effectiveness of the various testing and treatment strategies employed for the febrile young infant.

Our study has several limitations. First, the validity of ICD‐9 diagnosis codes for identifying young infants with fever is not well established, and thus our study is subject to misclassification bias. To minimize missed patients, we included infants with either an ICD‐9 admission or discharge diagnosis of fever; however, utilization of diagnosis codes for patient identification may have resulted in undercapture of infants with a measured temperature of 38.0C. It is also possible that some patients who did not undergo testing were misclassified as having a fever or had temperatures below standard thresholds to prompt diagnostic testing. This is a potential reason that testing was not performed in 100% of infants, even at hospitals with CPGs that recommended testing for all patients. Additionally, some febrile infants diagnosed with SBI may not have an associated ICD‐9 diagnosis code for fever. Although the overall SBI rate observed in our study was similar to prior studies,[4, 31] the rate in neonates 28 days of age was lower than reported in recent investigations,[2, 3] which may indicate inclusion of a higher proportion of low‐risk febrile infants. With the exception of bronchiolitis, we also did not assess diagnostic testing in the presence of other identified sources of infection such as herpes simplex virus.

Second, we were unable to assess the presence or absence of a CPG at the 4 excluded EDs that did not respond to the survey or the institutions excluded for data‐quality issues. However, included and excluded hospitals did not differ in region or annual ED volume (data not shown).

Third, although we classified hospitals based upon the presence and content of CPGs, we were unable to fully evaluate adherence to the CPG at each site.

Last, though PHIS hospitals represent 85% of freestanding children's hospitals, many febrile infants are hospitalized at non‐PHIS institutions; our results may not be generalizable to care provided at nonchildren's hospitals.

CONCLUSIONS