User login

Association of Weekend Admission and Weekend Discharge with Length of Stay and 30-Day Readmission in Children’s Hospitals

Increasingly, metrics such as length of stay (LOS) and readmissions are being utilized in the United States to assess quality of healthcare because these factors may represent opportunities to reduce cost and improve healthcare delivery.1-8 However, the relatively low rate of pediatric readmissions,9 coupled with limited data regarding recommended LOS or best practices to prevent readmissions in children, challenges the ability of hospitals to safely reduce LOS and readmission rates for children.10–12

In adults, weekend admission is associated with prolonged LOS, increased readmission rates, and increased risk of mortality.13-21 This association is referred to as the “weekend effect.” While the weekend effect has been examined in children, the results of these studies have been variable, with some studies supporting this association and others refuting it.22-31 In contrast to patient demographic and clinical characteristics that are known to affect LOS and readmissions,32 the weekend effect represents a potentially modifiable aspect of a hospitalization that could be targeted to improve healthcare delivery.

With increasing national attention toward improving quality of care and reducing LOS and healthcare costs, more definitive evidence of the weekend effect is necessary to prioritize resource use at both the local and national levels. Therefore, we sought to determine the association of weekend admission and weekend discharge on LOS and 30-day readmissions, respectively, among a national cohort of children. We hypothesized that children admitted on the weekend would have longer LOS, whereas those discharged on the weekend would have higher readmission rates.

METHODS

Study Design and Data Source

We conducted a multicenter, retrospective, cross-sectional study. Data were obtained from the Pediatric Health Information System (PHIS), an administrative and billing database of 46 free-standing tertiary care pediatric hospitals affiliated with the Children’s Hospital Association (Lenexa, Kansas). Patient data are de-identified within PHIS; however, encrypted patient identifiers allow individual patients to be followed across visits. This study was not considered human subjects research by the policies of the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Institutional Review Board.

Participants

We included hospitalizations to a PHIS-participating hospital for children aged 0-17 years between October 1, 2014 and September 30, 2015. We excluded children who were transferred from/to another institution, left against medical advice, or died in the hospital because these indications may result in incomplete LOS information and would not consistently contribute to readmission rates. We also excluded birth hospitalizations and children admitted for planned procedures. Birth hospitalizations were defined as hospitalizations that began on the day of birth.

Main Exposures

No standard definition of weekend admission or discharge was identified in the literature.33 Thus, we defined a weekend admission as an admission between 3:00

Main Outcomes

Our outcomes included LOS for weekend admission and 30-day readmissions for weekend discharge. LOS, measured in hours, was defined using the reported admission and discharge times. Readmissions were defined as a return to the same hospital within the subsequent 30 days following discharge.

Patient Demographics and Other Study Variables

Patient demographics included age, gender, race/ethnicity, payer, and median household income quartile based on the patient’s home ZIP code. Other study variables included presence of a complex chronic condition (CCC),34 technology dependence,34 number of chronic conditions of any complexity, admission through the emergency department, intensive care unit (ICU) admission, and case mix index. ICU admission and case mix index were chosen as markers for severity of illness. ICU admission was defined as any child who incurred ICU charges at any time following admission. Case mix index in PHIS is a relative weight assigned to each discharge based on the All-Patient Refined Diagnostic Group (APR-DRG; 3M) assignment and APR-DRG severity of illness, which ranges from 1 (minor) to 4 (extreme). The weights are derived by the Children’s Hospital Association from the HCUP KID 2012 database as the ratio of the average cost for discharges within a specific APR-DRG severity of illness combination to the average cost for all discharges in the database.

Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables were summarized with medians and interquartile ranges, while categorical variables were summarized with frequencies and percentages. Differences in admission and discharge characteristics between weekend and weekday were assessed using Wilcoxon rank sum tests for continuous variables and chi-square tests of association for categorical variables. We used generalized linear mixed modeling (GLMM) techniques to assess the impact of weekend admission on LOS and weekend discharge on readmission, adjusting for important patient demographic and clinical characteristics. Furthermore, we used GLMM point estimates to describe the variation across hospitals of the impact of weekday versus weekend care on LOS and readmissions. We assumed an underlying log-normal distribution for LOS and an underlying binomial distribution for 30-day readmission. All GLMMs included a random intercept for each hospital to account for patient clustering within a hospital. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS v.9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina), and P values <.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

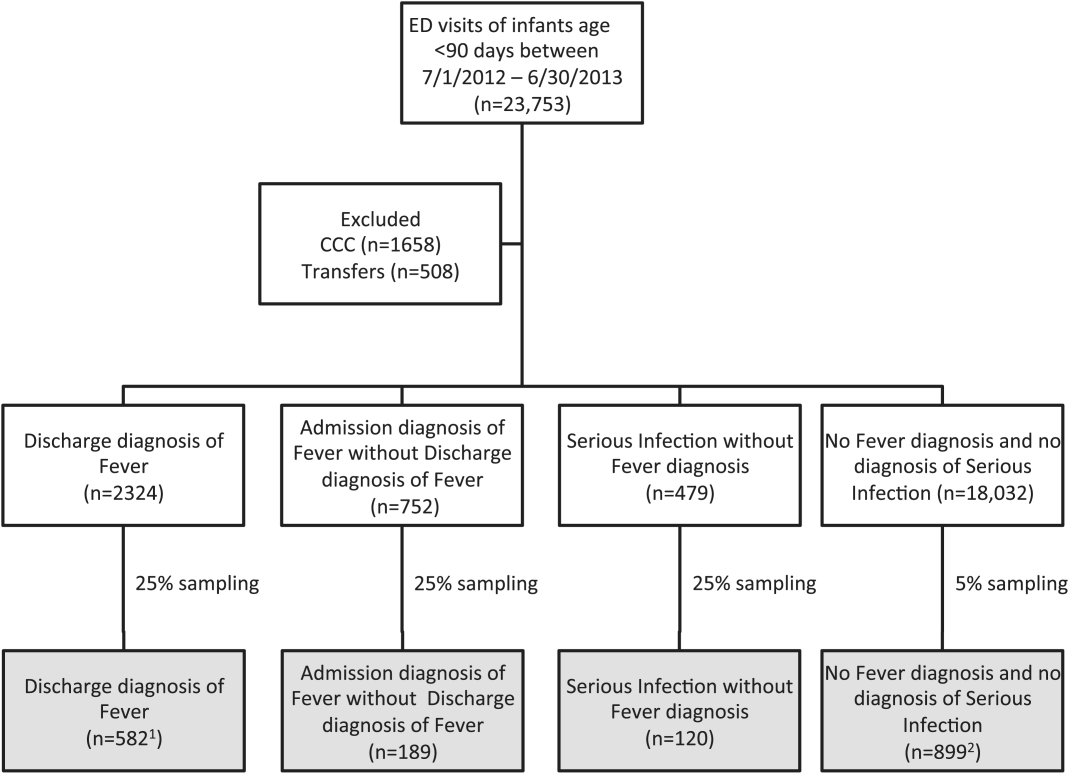

We identified 390,745 hospitalizations that met inclusion criteria (Supplementary Figure 1). The median LOS among our cohort was 41 hours (interquartile range [IQR] 24-71) and the median 30-day readmission rate was 8.2% (IQR 7.2-9.4).

Admission Demographics for Weekends and Weekdays

Among the included hospitalizations, 92,266 (23.6%) admissions occurred on a weekend (Supplementary Table 1). Overall, a higher percentage of children <5 years of age were admitted on a weekend compared with those admitted on a weekday (53.3% vs 49.1%, P < .001). We observed a small but statistically significant difference in the proportion of weekend versus weekday admissions according to gender, race/ethnicity, payer, and median household income quartile. Children with medical complexity and those with technology dependence were admitted less frequently on a weekend. A higher proportion of children were admitted through the emergency department on a weekend and a higher frequency of ICU utilization was observed for children admitted on a weekend compared with those admitted on a weekday.

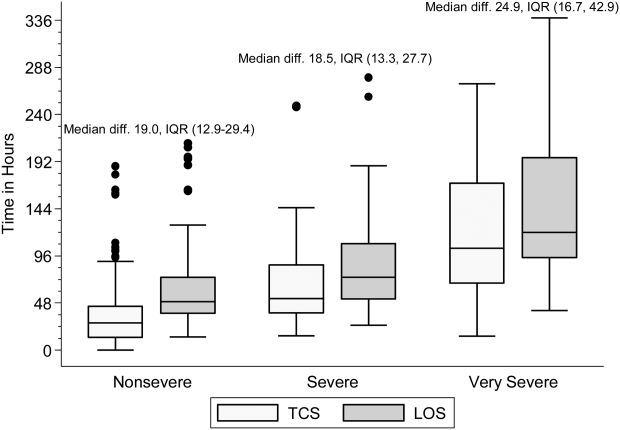

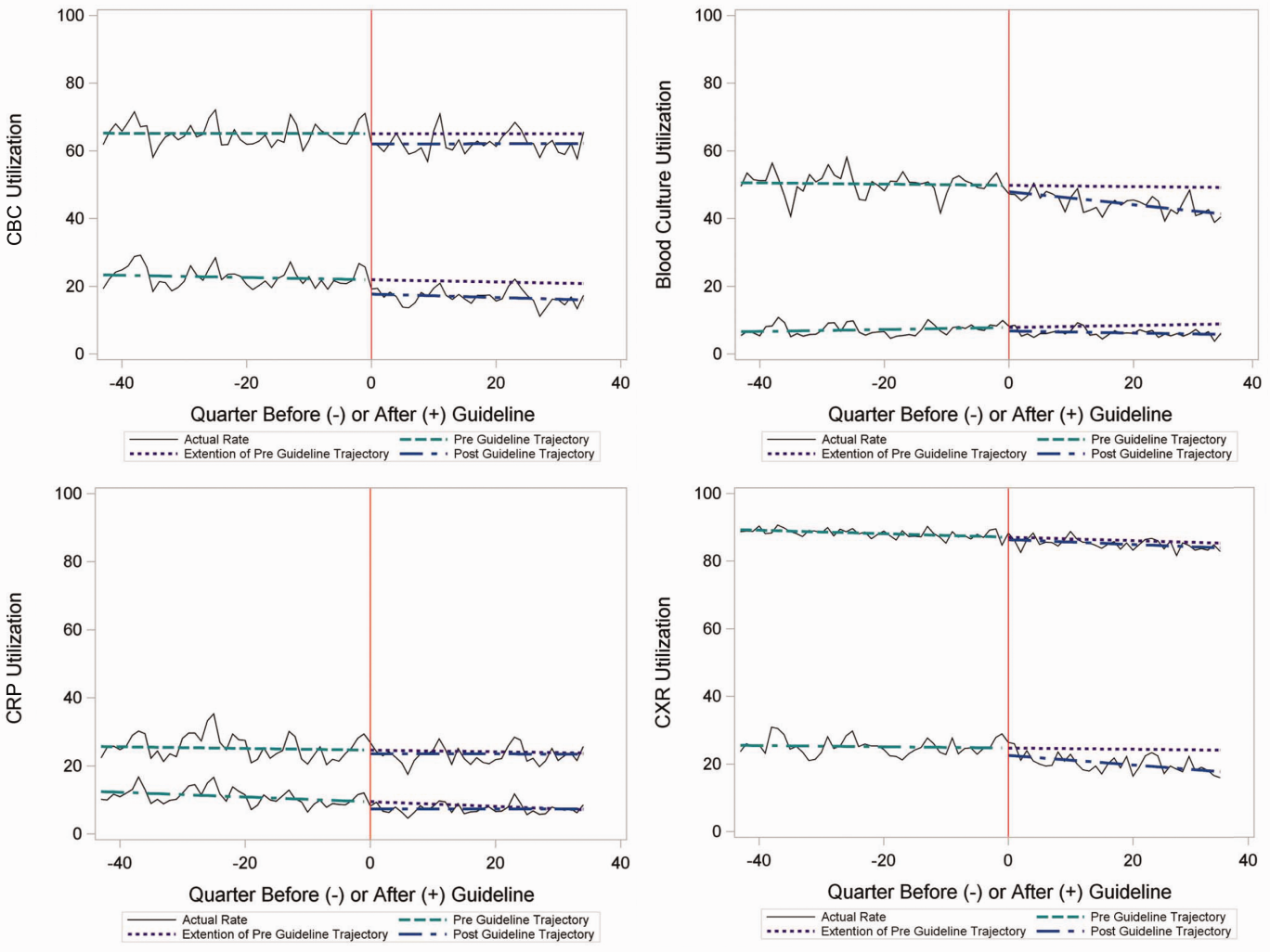

Association Between Study Variables and Length of Stay

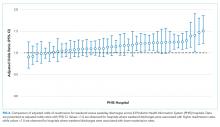

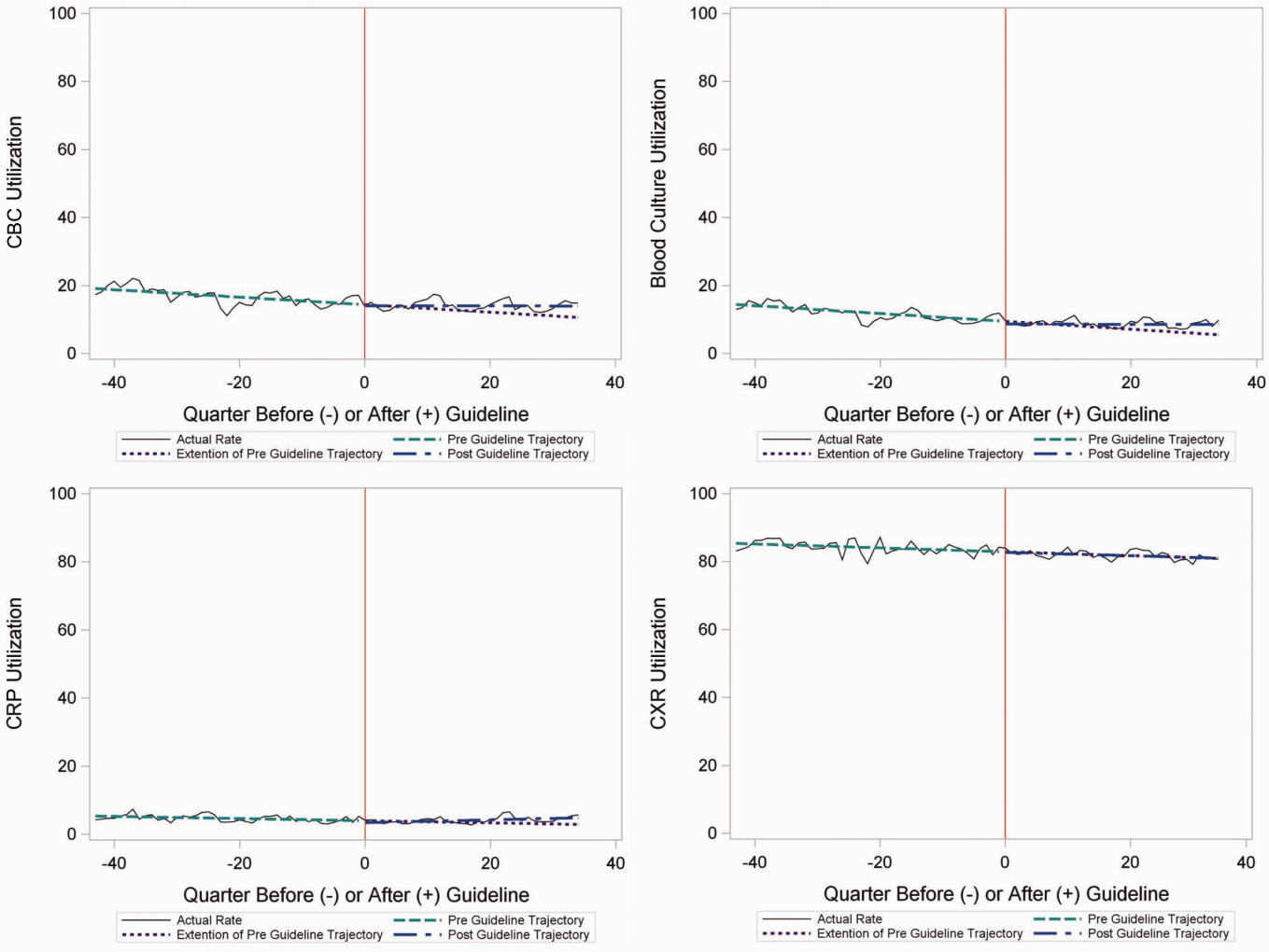

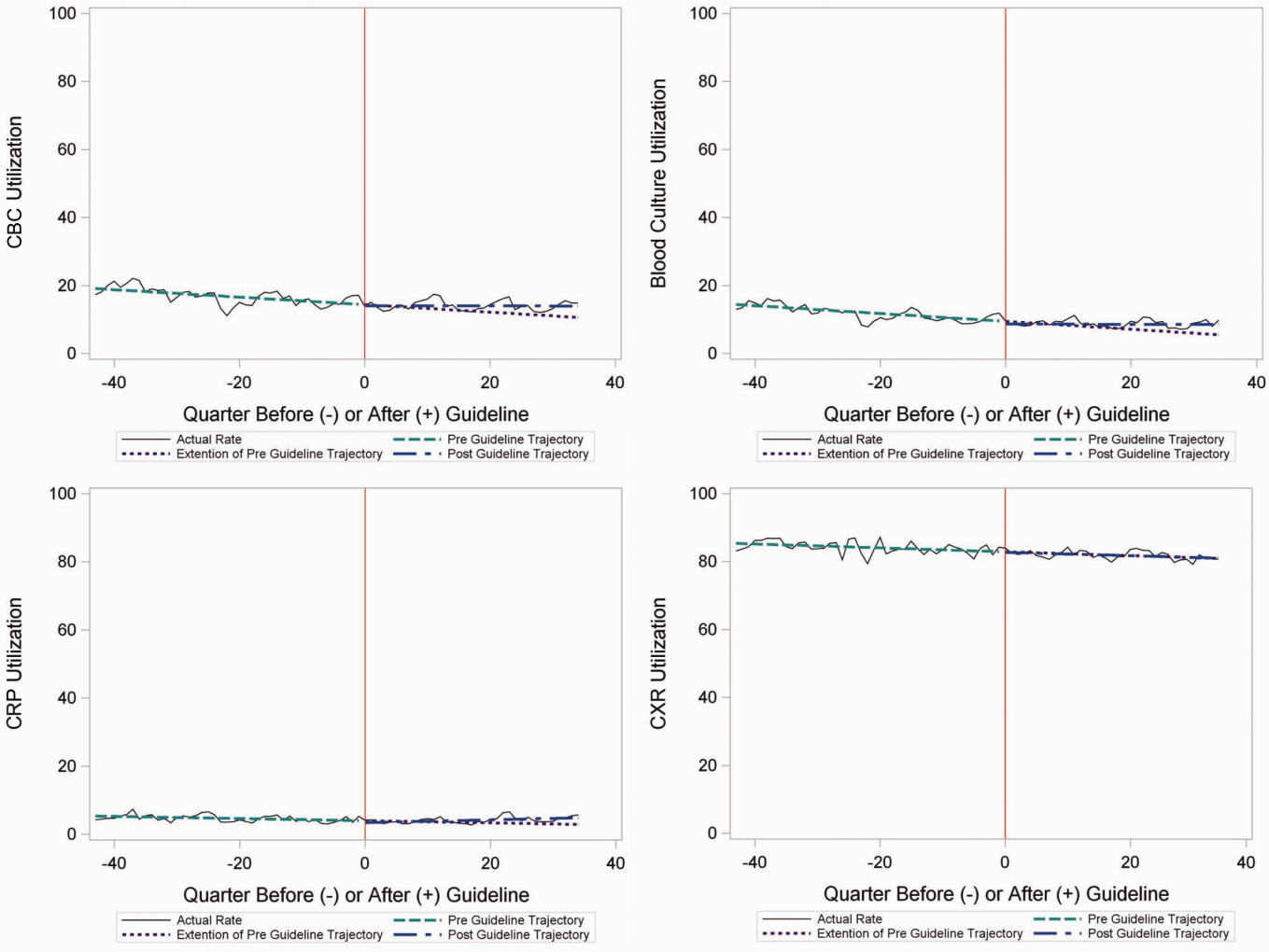

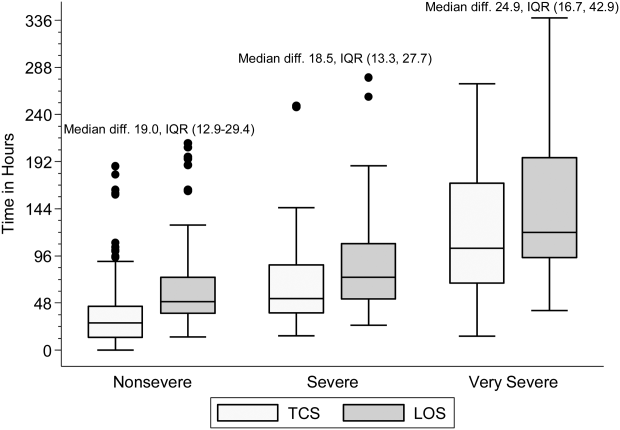

In comparing adjusted LOS for weekend versus weekday admissions across 43 hospitals, not only did LOS vary across hospitals (P < .001), but the association between LOS and weekend versus weekday care also varied across hospitals (P < .001) (Figure 1). Weekend admission was associated with a significantly longer LOS at eight (18.6%) hospitals and a significantly shorter LOS at four (9.3%) hospitals with nonstatistically significant differences at the remaining hospitals.

In adjusted analyses, we observed that infants ≤30 days of age, on average, had an adjusted LOS that was 24% longer than that of 15- to 17-year-olds, while children aged 1-14 years had an adjusted LOS that was 6%-18% shorter (Table 1). ICU utilization, admission through the emergency department, and number of chronic conditions had the greatest association with LOS. As the number of chronic conditions increased, the LOS increased. No association was found between weekend versus weekday admission and LOS (adjusted LOS [95% CI]: weekend 63.70 [61.01-66.52] hours versus weekday 63.40 [60.73-66.19] hours, P = .112).

Discharge Demographics for Weekends and Weekdays

Of the included hospitalizations, 127,421 (32.6%) discharges occurred on a weekend (Supplementary Table 2). Overall, a greater percentage of weekend discharges comprised children <5 years of age compared with the percentage of weekday discharges for children <5 years of age (51.5% vs 49.5%, P < .001). No statistically significant differences were found in gender, payer, or median household income quartile between those children discharged on a weekend versus those discharged on a weekday. We found small, statistically significant differences in the proportion of weekend versus weekday discharges according to race/ethnicity, with fewer non-Hispanic white children being discharged on the weekend versus weekday. Children with medical complexity, technology dependence, and patients with ICU utilization were less frequently discharged on a weekend compared with those discharged on a weekday.

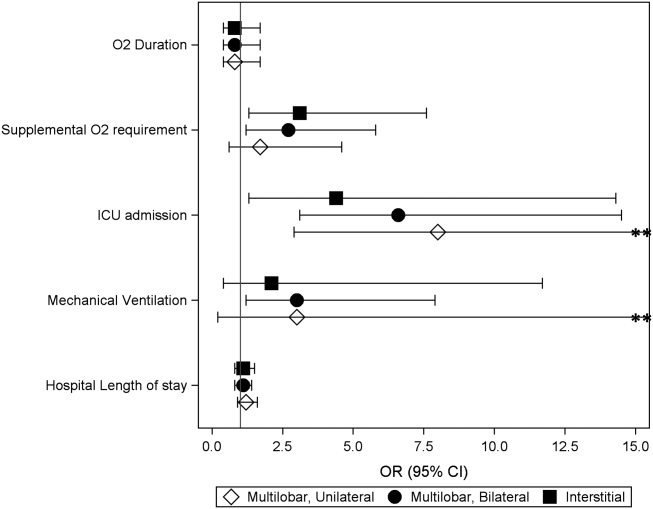

Association Between Study Variables and Readmissions

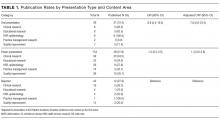

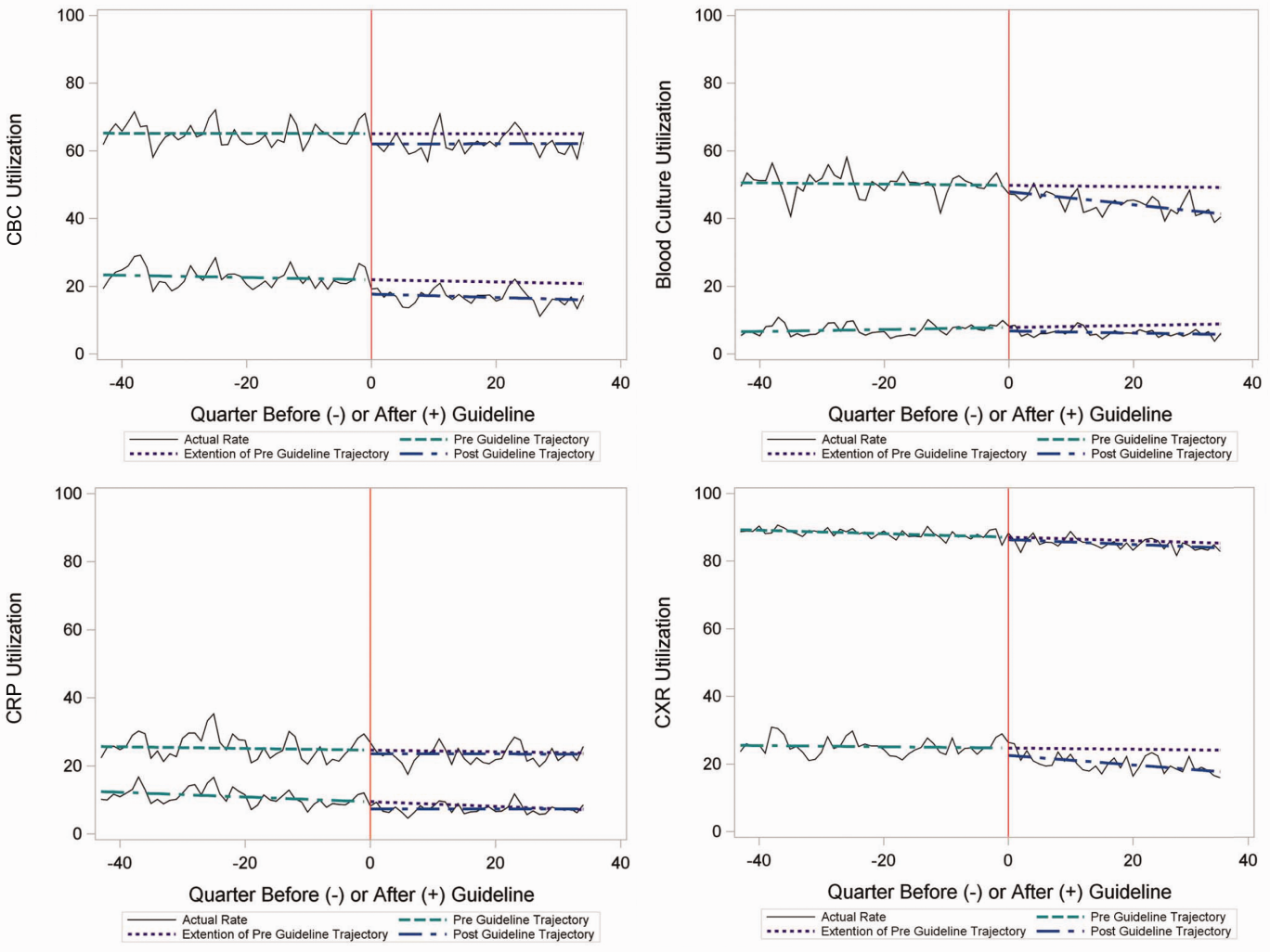

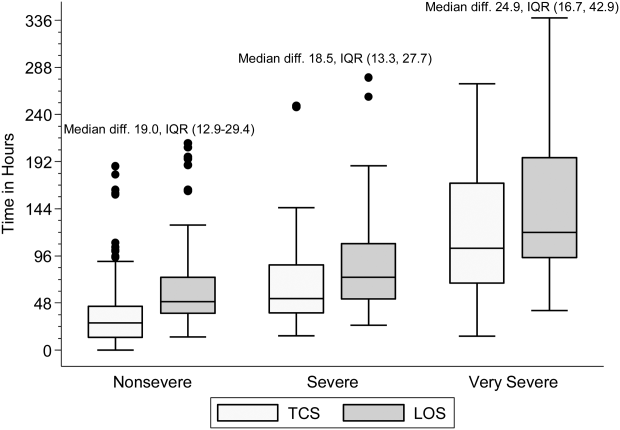

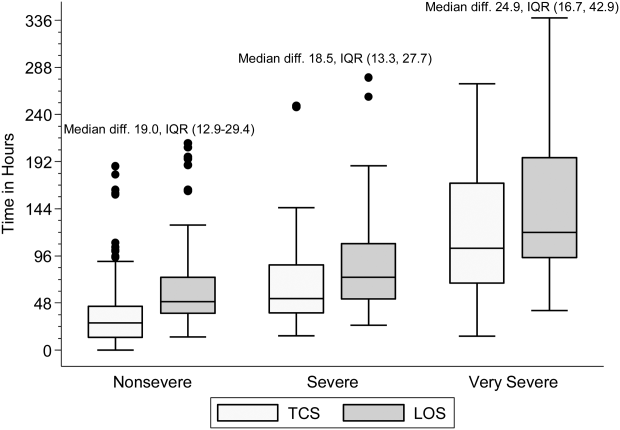

In comparing the adjusted odds of readmissions for weekend versus weekday discharges across 43 PHIS hospitals, we observed significant variation (P < .001) in readmission rates from hospital to hospital (Figure 2). However, the direction of impact of weekend care on readmissions was similar (P = .314) across hospitals (ie, for 37 of 43 hospitals, the readmission rate was greater for weekend discharges compared with that for weekday discharges). For 17 (39.5%) of 43 hospitals, weekend discharge was associated with a significantly higher readmission rate, while the differences between weekday and weekend discharge were not statistically significant for the remaining hospitals.

In adjusted analyses, we observed that infants <1 year were more likely to be readmitted compared with 15- to 17-year-olds, while children 5-14 years of age were less likely to be readmitted (Table 2). Medical complexity and the number of chronic conditions had the greatest association with readmissions, with increased likelihood of readmission observed as the number of chronic conditions increased. Weekend discharge was associated with increased probability of readmission compared with weekday discharge (adjusted probability of readmission [95% CI]: weekend 0.13 [0.12-0.13] vs weekday 0.11 [0.11-0.12], P < .001).

DISCUSSION

While the reasons for the weekend effect are unclear, data supporting this difference have been observed across many diverse patient groups and health systems both nationally and internationally.13-27,31 Weekend care is thought to differ from weekday care because of differences in physician and nurse staffing, availability of ancillary services, access to diagnostic testing and therapeutic interventions, ability to arrange outpatient follow-up, and individual patient clinical factors, including acuity of illness. Few studies have assessed the effect of weekend discharges on patient or system outcomes. Among children within a single health system, readmission risk was associated with weekend admission but not with weekend discharge.22 This observation suggests that if differential care exists, then it occurs during initial clinical management rather than during discharge planning. Consequently, understanding the interaction of weekend admission and LOS is important. In addition, the relative paucity of pediatric data examining a weekend discharge effect limits the ability to generalize these findings across other hospitals or health systems.

In contrast to prior work, we observed a modest increased risk for readmission among those discharged on the weekend in a large sample of children. Auger and Davis reported a lack of association between weekend discharge and readmissions at one tertiary care children’s hospital, citing reduced discharge volumes on the weekend, especially among children with medical complexity, as a possible driver for their observation.22 The inclusion of a much larger population across 43 hospitals in our study may explain our different findings compared with previous research. In addition, the inclusion/exclusion criteria differed between the two studies; we excluded index admissions for planned procedures in this study (which are more likely to occur during the week), which may have contributed to the differing conclusions. Although Auger and Davis suggest that differences in initial clinical management may be responsible for the weekend effect,22 our observations suggest that discharge planning practices may also contribute to readmission risk. For example, a family’s inability to access compounded medications at a local pharmacy or to access primary care following discharge could reasonably contribute to treatment failure and increased readmission risk. Attention to improving and standardizing discharge practices may alleviate differences in readmission risk among children discharged on a weekend.

Individual patient characteristics greatly influence LOS and readmission risk. Congruent with prior studies, medical complexity and technology dependence were among the factors in our study that had the strongest association with LOS and readmission risk.32 As with prior studies22, we observed that children with medical complexity and technology dependence were less frequently admitted and discharged on a weekend than on a weekday, which suggests that physicians may avoid complicated discharges on the weekend. Children with medical complexity present a unique challenge to physicians when assessing discharge readiness, given that these children frequently require careful coordination of durable medical equipment, obtainment of special medication preparations, and possibly the resumption or establishment of home health services. Notably, we cannot discern from our data what proportion of discharges may be delayed over the weekend secondary to challenges involved in coordinating care for children with medical complexity. Future investigations aimed at assessing physician decision making and discharge readiness in relation to discharge timing among children with medical complexity may establish this relationship more clearly.

We observed substantial variation in LOS and readmission risk across 43 tertiary care children’s hospitals. Since the 1970s, numerous studies have reported worse outcomes among patients admitted on the weekend. While the majority of studies support the weekend effect, several recent studies suggest that patients admitted on the weekend are at no greater risk of adverse outcomes than those admitted during the week.35-37 Our work builds on the existing literature, demonstrating a complex and variable relationship between weekend admission/discharge, LOS, and readmission risk across hospitals. Notably, while many hospitals in our study experienced a significant weekend effect in LOS or readmission risk, only four hospitals experienced a statistically significant weekend effect for both LOS and readmission risk (three hospitals experienced increased risk for both, while one hospital experienced increased readmission risk but decreased LOS). Future investigations of the weekend effect should focus on exploring the differences in admission/discharge practices and staffing patterns of hospitals that did or did not experience a weekend effect.

This study has several limitations

CONCLUSION

In a study of 43 children’s hospitals, children discharged on the weekend had a slightly increased readmission risk compared with children discharged on a weekday. Wide variation in the weekend effect on LOS and readmission risk was evident across hospitals. Individual patient characteristics had a greater impact on LOS and readmission risk than the weekend effect. Future investigations aimed at understanding which factors contribute most strongly to a weekend effect within individual hospitals (eg, differences in institutional admission/discharge practices) may help alleviate the weekend effect and improve healthcare quality.

Acknowledgments

This manuscript resulted from “Paper in a Day,” a Pediatric Research in Inpatient Settings (PRIS) Network-sponsored workshop presented at the Pediatric Hospital Medicine 2017 annual meeting. Workshop participants learned how to ask and answer a health services research question and efficiently prepare a manuscript for publication. The following are the members of the PRIS Network who contributed to this work: Jessica L. Bettenhausen, MD; Rebecca M. Cantu, MD, MPH; Jillian M Cotter, MD; Megan Deisz, MD; Teresa Frazer, MD; Pratichi Goenka, MD; Ashley Jenkins, MD; Kathryn E. Kyler, MD; Janet T. Lau, MD; Brian E. Lee, MD; Christiane Lenzen, MD; Trisha Marshall, MD; John M. Morrison MD, PhD; Lauren Nassetta, MD; Raymond Parlar-Chun, MD; Sonya Tang Girdwood MD, PhD; Tony R Tarchichi, MD; Irina G. Trifonova, MD; Jacqueline M. Walker, MD, MHPE; and Susan C. Walley, MD. See appendix for contact information for members of the PRIS Network

Funding

The authors have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

1. Crossing the Quality Chasm: The IOM Health Care Quality Initiative : Health and Medicine Division. http://www.nationalacademies.org/hmd/Global/News%20Announcements/Crossing-the-Quality-Chasm-The-IOM-Health-Care-Quality-Initiative.aspx. Accessed November 20, 2017.

2. Institute for Healthcare Improvement: IHI Home Page. http://www.ihi.org:80/Pages/default.aspx. Accessed November 20, 2017.

3. Berry JG, Zaslavsky AM, Toomey SL, et al. Recognizing differences in hospital quality performance for pediatric inpatient care. Pediatrics. 2015;136(2):251-262. doi:10.1542/peds.2014-3131

4. NQF: All-Cause Admissions and Readmissions Measures - Final Report. http://www.qualityforum.org/Publications/2015/04/All-Cause_Admissions_and_Readmissions_Measures_-_Final_Report.aspx. Accessed March 24, 2018.

5. Hospital Inpatient Potentially Preventable Readmissions Information and Reports. https://www.illinois.gov/hfs/MedicalProviders/hospitals/PPRReports/Pages/default.aspx. Accessed November 6, 2016.

6. Potentially Preventable Readmissions in Texas Medicaid and CHIP Programs - Fiscal Year 2013 | Texas Health and Human Services. https://hhs.texas.gov/reports/2016/08/potentially-preventable-readmissions-texas-medicaid-and-chip-programs-fiscal-year. Accessed November 6, 2016.

7. Statewide Planning and Research Cooperative System. http://www.health.ny.gov/statistics/sparcs/sb/. Accessed November 6, 2016.

8. HCA Implements Potentially Preventable Readmission (PPR) Adjustments. Wash State Hosp Assoc. http://www.wsha.org/articles/hca-implements-potentially-preventable-readmission-ppr-adjustments/. Accessed November 8, 2016.

9. Berry JG, Toomey SL, Zaslavsky AM, et al. Pediatric readmission prevalence and variability across hospitals. JAMA. 2013;309(4):372-380. doi:10.1001/jama.2012.188351 PubMed

10. Bardach NS, Vittinghoff E, Asteria-Peñaloza R, et al. Measuring hospital quality using pediatric readmission and revisit rates. Pediatrics. 2013;132(3):429-436. doi:10.1542/peds.2012-3527 PubMed

11. Berry JG, Blaine K, Rogers J, et al. A framework of pediatric hospital discharge care informed by legislation, research, and practice. JAMA Pediatr. 2014;168(10):955-962; quiz 965-966. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.891 PubMed

12. Auger KA, Simon TD, Cooperberg D, et al. Summary of STARNet: seamless transitions and (Re)admissions network. Pediatrics. 2015;135(1):164. doi:10.1542/peds.2014-1887 PubMed

13. Freemantle N, Ray D, McNulty D, et al. Increased mortality associated with weekend hospital admission: a case for expanded seven day services? BMJ. 2015;351:h4596. doi:10.1136/bmj.h4596 PubMed

14. Schilling PL, Campbell DA, Englesbe MJ, Davis MM. A comparison of in-hospital mortality risk conferred by high hospital occupancy, differences in nurse staffing levels, weekend admission, and seasonal influenza. Med Care. 2010;48(3):224-232. doi:10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181c162c0 PubMed

15. Cram P, Hillis SL, Barnett M, Rosenthal GE. Effects of weekend admission and hospital teaching status on in-hospital mortality. Am J Med. 2004;117(3):151-157. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2004.02.035 PubMed

16. Zapf MAC, Kothari AN, Markossian T, et al. The “weekend effect” in urgent general operative procedures. Surgery. 2015;158(2):508-514. doi:10.1016/j.surg.2015.02.024 PubMed

17. Freemantle N, Richardson M, Wood J, et al. Weekend hospitalization and additional risk of death: an analysis of inpatient data. J R Soc Med. 2012;105(2):74-84. doi:10.1258/jrsm.2012.120009 PubMed

18. Bell CM, Redelmeier DA. Mortality among patients admitted to hospitals on weekends as compared with weekdays. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(9):663-668. doi:10.1056/NEJMsa003376 PubMed

19. Coiera E, Wang Y, Magrabi F, Concha OP, Gallego B, Runciman W. Predicting the cumulative risk of death during hospitalization by modeling weekend, weekday and diurnal mortality risks. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:226. doi:10.1186/1472-6963-14-226 PubMed

20. Powell ES, Khare RK, Courtney DM, Feinglass J. The weekend effect for patients with sepsis presenting to the emergency department. J Emerg Med. 2013;45(5):641-648. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2013.04.042 PubMed

21. Ananthakrishnan AN, McGinley EL, Saeian K. Outcomes of weekend admissions for upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage: a nationwide analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol Off Clin Pract J Am Gastroenterol Assoc. 2009;7(3):296-302e1. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2008.08.013 PubMed

22. Auger KA, Davis MM. Pediatric weekend admission and increased unplanned readmission rates. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(11):743-745. doi:10.1002/jhm.2426 PubMed

23. Goldstein SD, Papandria DJ, Aboagye J, et al. The “weekend effect” in pediatric surgery - increased mortality for children undergoing urgent surgery during the weekend. J Pediatr Surg. 2014;49(7):1087-1091. doi:10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2014.01.001 PubMed

24. Adil MM, Vidal G, Beslow LA. Weekend effect in children with stroke in the nationwide inpatient sample. Stroke. 2016;47(6):1436-1443. doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.116.013453 PubMed

25. McCrory MC, Spaeder MC, Gower EW, et al. Time of admission to the PICU and mortality. Pediatr Crit Care Med J Soc Crit Care Med World Fed Pediatr Intensive Crit Care Soc. 2017;18(10):915-923. doi:10.1097/PCC.0000000000001268 PubMed

26. Mangold WD. Neonatal mortality by the day of the week in the 1974-75 Arkansas live birth cohort. Am J Public Health. 1981;71(6):601-605. PubMed

27. MacFarlane A. Variations in number of births and perinatal mortality by day of week in England and Wales. Br Med J. 1978;2(6153):1670-1673. PubMed

28. McShane P, Draper ES, McKinney PA, McFadzean J, Parslow RC, Paediatric intensive care audit network (PICANet). Effects of out-of-hours and winter admissions and number of patients per unit on mortality in pediatric intensive care. J Pediatr. 2013;163(4):1039-1044.e5. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2013.03.061 PubMed

29. Hixson ED, Davis S, Morris S, Harrison AM. Do weekends or evenings matter in a pediatric intensive care unit? Pediatr Crit Care Med J Soc Crit Care Med World Fed Pediatr Intensive Crit Care Soc. 2005;6(5):523-530. PubMed

30. Gonzalez KW, Dalton BGA, Weaver KL, Sherman AK, St Peter SD, Snyder CL. Effect of timing of cannulation on outcome for pediatric extracorporeal life support. Pediatr Surg Int. 2016;32(7):665-669. doi:10.1007/s00383-016-3901-6 PubMed

31. Desai V, Gonda D, Ryan SL, et al. The effect of weekend and after-hours surgery on morbidity and mortality rates in pediatric neurosurgery patients. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2015;16(6):726-731. doi:10.3171/2015.6.PEDS15184 PubMed

32. Berry JG, Hall DE, Kuo DZ, et al. Hospital utilization and characteristics of patients experiencing recurrent readmissions within children’s hospitals. JAMA. 2011;305(7):682-690. doi:10.1001/jama.2011.122 PubMed

33. Hoshijima H, Takeuchi R, Mihara T, et al. Weekend versus weekday admission and short-term mortality: A meta-analysis of 88 cohort studies including 56,934,649 participants. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96(17):e6685. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000006685 PubMed

34. Feudtner C, Feinstein JA, Zhong W, Hall M, Dai D. Pediatric complex chronic conditions classification system version 2: updated for ICD-10 and complex medical technology dependence and transplantation. BMC Pediatr. 2014;14:199. doi:10.1186/1471-2431-14-199 PubMed

35. Li L, Rothwell PM, Oxford Vascular Study. Biases in detection of apparent “weekend effect” on outcome with administrative coding data: population based study of stroke. BMJ. 2016;353:i2648. doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.i2648 PubMed

36. Bray BD, Cloud GC, James MA, et al. Weekly variation in health-care quality by day and time of admission: a nationwide, registry-based, prospective cohort study of acute stroke care. The Lancet. 2016;388(10040):170-177. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30443-3 PubMed

37. Ko SQ, Strom JB, Shen C, Yeh RW. Mortality, Length of Stay, and Cost of Weekend Admissions. J Hosp Med. 2018. doi:10.12788/jhm.2906 PubMed

38. Tubbs-Cooley HL, Cimiotti JP, Silber JH, Sloane DM, Aiken LH. An observational study of nurse staffing ratios and hospital readmission among children admitted for common conditions. BMJ Qual Saf. 2013;22(9):735-742. doi:10.1136/bmjqs-2012-001610 PubMed

39. Ong M, Bostrom A, Vidyarthi A, McCulloch C, Auerbach A. House staff team workload and organization effects on patient outcomes in an academic general internal medicine inpatient service. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(1):47-52. doi:10.1001/archinte.167.1.47 PubMed

Increasingly, metrics such as length of stay (LOS) and readmissions are being utilized in the United States to assess quality of healthcare because these factors may represent opportunities to reduce cost and improve healthcare delivery.1-8 However, the relatively low rate of pediatric readmissions,9 coupled with limited data regarding recommended LOS or best practices to prevent readmissions in children, challenges the ability of hospitals to safely reduce LOS and readmission rates for children.10–12

In adults, weekend admission is associated with prolonged LOS, increased readmission rates, and increased risk of mortality.13-21 This association is referred to as the “weekend effect.” While the weekend effect has been examined in children, the results of these studies have been variable, with some studies supporting this association and others refuting it.22-31 In contrast to patient demographic and clinical characteristics that are known to affect LOS and readmissions,32 the weekend effect represents a potentially modifiable aspect of a hospitalization that could be targeted to improve healthcare delivery.

With increasing national attention toward improving quality of care and reducing LOS and healthcare costs, more definitive evidence of the weekend effect is necessary to prioritize resource use at both the local and national levels. Therefore, we sought to determine the association of weekend admission and weekend discharge on LOS and 30-day readmissions, respectively, among a national cohort of children. We hypothesized that children admitted on the weekend would have longer LOS, whereas those discharged on the weekend would have higher readmission rates.

METHODS

Study Design and Data Source

We conducted a multicenter, retrospective, cross-sectional study. Data were obtained from the Pediatric Health Information System (PHIS), an administrative and billing database of 46 free-standing tertiary care pediatric hospitals affiliated with the Children’s Hospital Association (Lenexa, Kansas). Patient data are de-identified within PHIS; however, encrypted patient identifiers allow individual patients to be followed across visits. This study was not considered human subjects research by the policies of the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Institutional Review Board.

Participants

We included hospitalizations to a PHIS-participating hospital for children aged 0-17 years between October 1, 2014 and September 30, 2015. We excluded children who were transferred from/to another institution, left against medical advice, or died in the hospital because these indications may result in incomplete LOS information and would not consistently contribute to readmission rates. We also excluded birth hospitalizations and children admitted for planned procedures. Birth hospitalizations were defined as hospitalizations that began on the day of birth.

Main Exposures

No standard definition of weekend admission or discharge was identified in the literature.33 Thus, we defined a weekend admission as an admission between 3:00

Main Outcomes

Our outcomes included LOS for weekend admission and 30-day readmissions for weekend discharge. LOS, measured in hours, was defined using the reported admission and discharge times. Readmissions were defined as a return to the same hospital within the subsequent 30 days following discharge.

Patient Demographics and Other Study Variables

Patient demographics included age, gender, race/ethnicity, payer, and median household income quartile based on the patient’s home ZIP code. Other study variables included presence of a complex chronic condition (CCC),34 technology dependence,34 number of chronic conditions of any complexity, admission through the emergency department, intensive care unit (ICU) admission, and case mix index. ICU admission and case mix index were chosen as markers for severity of illness. ICU admission was defined as any child who incurred ICU charges at any time following admission. Case mix index in PHIS is a relative weight assigned to each discharge based on the All-Patient Refined Diagnostic Group (APR-DRG; 3M) assignment and APR-DRG severity of illness, which ranges from 1 (minor) to 4 (extreme). The weights are derived by the Children’s Hospital Association from the HCUP KID 2012 database as the ratio of the average cost for discharges within a specific APR-DRG severity of illness combination to the average cost for all discharges in the database.

Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables were summarized with medians and interquartile ranges, while categorical variables were summarized with frequencies and percentages. Differences in admission and discharge characteristics between weekend and weekday were assessed using Wilcoxon rank sum tests for continuous variables and chi-square tests of association for categorical variables. We used generalized linear mixed modeling (GLMM) techniques to assess the impact of weekend admission on LOS and weekend discharge on readmission, adjusting for important patient demographic and clinical characteristics. Furthermore, we used GLMM point estimates to describe the variation across hospitals of the impact of weekday versus weekend care on LOS and readmissions. We assumed an underlying log-normal distribution for LOS and an underlying binomial distribution for 30-day readmission. All GLMMs included a random intercept for each hospital to account for patient clustering within a hospital. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS v.9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina), and P values <.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

We identified 390,745 hospitalizations that met inclusion criteria (Supplementary Figure 1). The median LOS among our cohort was 41 hours (interquartile range [IQR] 24-71) and the median 30-day readmission rate was 8.2% (IQR 7.2-9.4).

Admission Demographics for Weekends and Weekdays

Among the included hospitalizations, 92,266 (23.6%) admissions occurred on a weekend (Supplementary Table 1). Overall, a higher percentage of children <5 years of age were admitted on a weekend compared with those admitted on a weekday (53.3% vs 49.1%, P < .001). We observed a small but statistically significant difference in the proportion of weekend versus weekday admissions according to gender, race/ethnicity, payer, and median household income quartile. Children with medical complexity and those with technology dependence were admitted less frequently on a weekend. A higher proportion of children were admitted through the emergency department on a weekend and a higher frequency of ICU utilization was observed for children admitted on a weekend compared with those admitted on a weekday.

Association Between Study Variables and Length of Stay

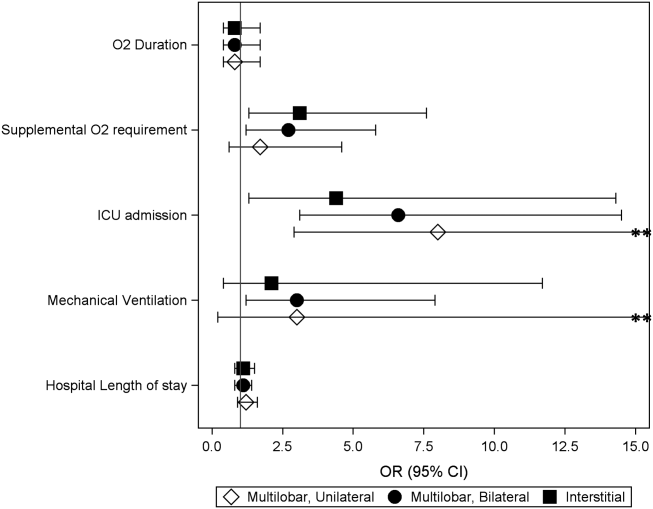

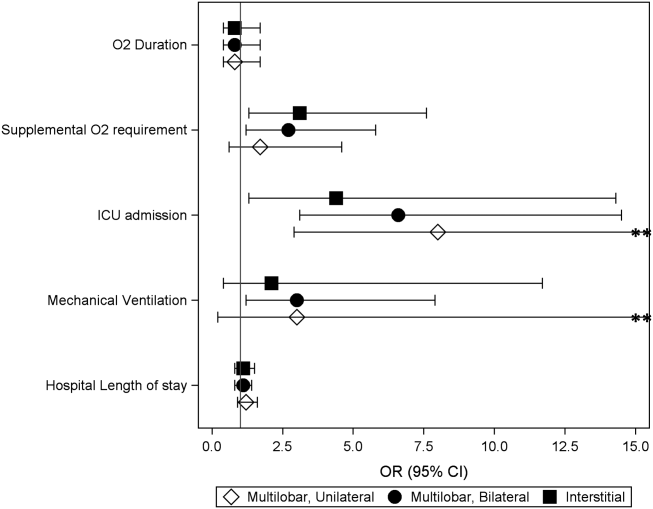

In comparing adjusted LOS for weekend versus weekday admissions across 43 hospitals, not only did LOS vary across hospitals (P < .001), but the association between LOS and weekend versus weekday care also varied across hospitals (P < .001) (Figure 1). Weekend admission was associated with a significantly longer LOS at eight (18.6%) hospitals and a significantly shorter LOS at four (9.3%) hospitals with nonstatistically significant differences at the remaining hospitals.

In adjusted analyses, we observed that infants ≤30 days of age, on average, had an adjusted LOS that was 24% longer than that of 15- to 17-year-olds, while children aged 1-14 years had an adjusted LOS that was 6%-18% shorter (Table 1). ICU utilization, admission through the emergency department, and number of chronic conditions had the greatest association with LOS. As the number of chronic conditions increased, the LOS increased. No association was found between weekend versus weekday admission and LOS (adjusted LOS [95% CI]: weekend 63.70 [61.01-66.52] hours versus weekday 63.40 [60.73-66.19] hours, P = .112).

Discharge Demographics for Weekends and Weekdays

Of the included hospitalizations, 127,421 (32.6%) discharges occurred on a weekend (Supplementary Table 2). Overall, a greater percentage of weekend discharges comprised children <5 years of age compared with the percentage of weekday discharges for children <5 years of age (51.5% vs 49.5%, P < .001). No statistically significant differences were found in gender, payer, or median household income quartile between those children discharged on a weekend versus those discharged on a weekday. We found small, statistically significant differences in the proportion of weekend versus weekday discharges according to race/ethnicity, with fewer non-Hispanic white children being discharged on the weekend versus weekday. Children with medical complexity, technology dependence, and patients with ICU utilization were less frequently discharged on a weekend compared with those discharged on a weekday.

Association Between Study Variables and Readmissions

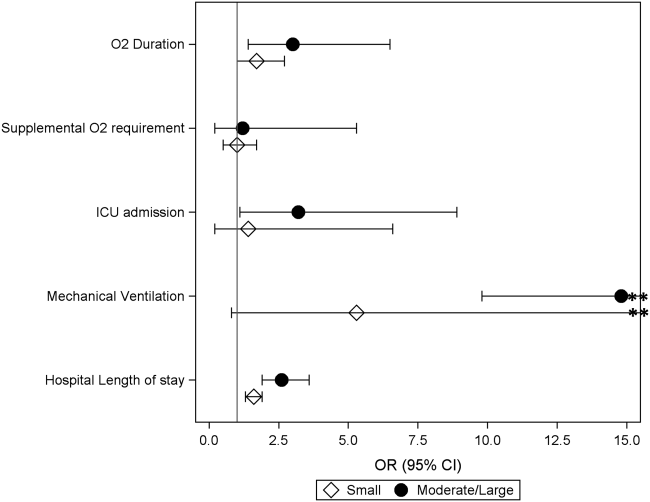

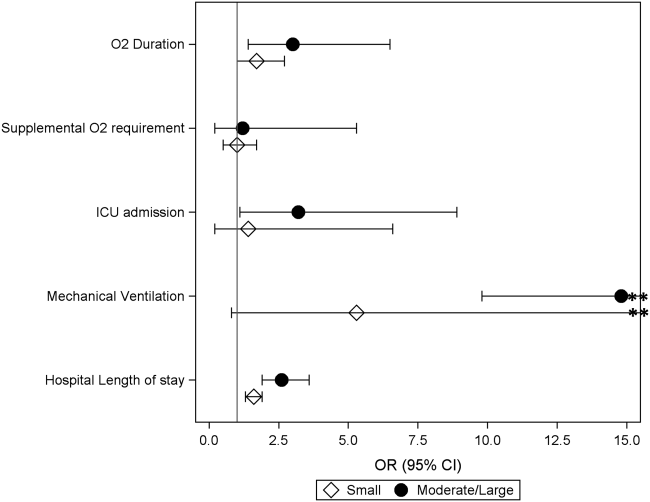

In comparing the adjusted odds of readmissions for weekend versus weekday discharges across 43 PHIS hospitals, we observed significant variation (P < .001) in readmission rates from hospital to hospital (Figure 2). However, the direction of impact of weekend care on readmissions was similar (P = .314) across hospitals (ie, for 37 of 43 hospitals, the readmission rate was greater for weekend discharges compared with that for weekday discharges). For 17 (39.5%) of 43 hospitals, weekend discharge was associated with a significantly higher readmission rate, while the differences between weekday and weekend discharge were not statistically significant for the remaining hospitals.

In adjusted analyses, we observed that infants <1 year were more likely to be readmitted compared with 15- to 17-year-olds, while children 5-14 years of age were less likely to be readmitted (Table 2). Medical complexity and the number of chronic conditions had the greatest association with readmissions, with increased likelihood of readmission observed as the number of chronic conditions increased. Weekend discharge was associated with increased probability of readmission compared with weekday discharge (adjusted probability of readmission [95% CI]: weekend 0.13 [0.12-0.13] vs weekday 0.11 [0.11-0.12], P < .001).

DISCUSSION

While the reasons for the weekend effect are unclear, data supporting this difference have been observed across many diverse patient groups and health systems both nationally and internationally.13-27,31 Weekend care is thought to differ from weekday care because of differences in physician and nurse staffing, availability of ancillary services, access to diagnostic testing and therapeutic interventions, ability to arrange outpatient follow-up, and individual patient clinical factors, including acuity of illness. Few studies have assessed the effect of weekend discharges on patient or system outcomes. Among children within a single health system, readmission risk was associated with weekend admission but not with weekend discharge.22 This observation suggests that if differential care exists, then it occurs during initial clinical management rather than during discharge planning. Consequently, understanding the interaction of weekend admission and LOS is important. In addition, the relative paucity of pediatric data examining a weekend discharge effect limits the ability to generalize these findings across other hospitals or health systems.

In contrast to prior work, we observed a modest increased risk for readmission among those discharged on the weekend in a large sample of children. Auger and Davis reported a lack of association between weekend discharge and readmissions at one tertiary care children’s hospital, citing reduced discharge volumes on the weekend, especially among children with medical complexity, as a possible driver for their observation.22 The inclusion of a much larger population across 43 hospitals in our study may explain our different findings compared with previous research. In addition, the inclusion/exclusion criteria differed between the two studies; we excluded index admissions for planned procedures in this study (which are more likely to occur during the week), which may have contributed to the differing conclusions. Although Auger and Davis suggest that differences in initial clinical management may be responsible for the weekend effect,22 our observations suggest that discharge planning practices may also contribute to readmission risk. For example, a family’s inability to access compounded medications at a local pharmacy or to access primary care following discharge could reasonably contribute to treatment failure and increased readmission risk. Attention to improving and standardizing discharge practices may alleviate differences in readmission risk among children discharged on a weekend.

Individual patient characteristics greatly influence LOS and readmission risk. Congruent with prior studies, medical complexity and technology dependence were among the factors in our study that had the strongest association with LOS and readmission risk.32 As with prior studies22, we observed that children with medical complexity and technology dependence were less frequently admitted and discharged on a weekend than on a weekday, which suggests that physicians may avoid complicated discharges on the weekend. Children with medical complexity present a unique challenge to physicians when assessing discharge readiness, given that these children frequently require careful coordination of durable medical equipment, obtainment of special medication preparations, and possibly the resumption or establishment of home health services. Notably, we cannot discern from our data what proportion of discharges may be delayed over the weekend secondary to challenges involved in coordinating care for children with medical complexity. Future investigations aimed at assessing physician decision making and discharge readiness in relation to discharge timing among children with medical complexity may establish this relationship more clearly.

We observed substantial variation in LOS and readmission risk across 43 tertiary care children’s hospitals. Since the 1970s, numerous studies have reported worse outcomes among patients admitted on the weekend. While the majority of studies support the weekend effect, several recent studies suggest that patients admitted on the weekend are at no greater risk of adverse outcomes than those admitted during the week.35-37 Our work builds on the existing literature, demonstrating a complex and variable relationship between weekend admission/discharge, LOS, and readmission risk across hospitals. Notably, while many hospitals in our study experienced a significant weekend effect in LOS or readmission risk, only four hospitals experienced a statistically significant weekend effect for both LOS and readmission risk (three hospitals experienced increased risk for both, while one hospital experienced increased readmission risk but decreased LOS). Future investigations of the weekend effect should focus on exploring the differences in admission/discharge practices and staffing patterns of hospitals that did or did not experience a weekend effect.

This study has several limitations

CONCLUSION

In a study of 43 children’s hospitals, children discharged on the weekend had a slightly increased readmission risk compared with children discharged on a weekday. Wide variation in the weekend effect on LOS and readmission risk was evident across hospitals. Individual patient characteristics had a greater impact on LOS and readmission risk than the weekend effect. Future investigations aimed at understanding which factors contribute most strongly to a weekend effect within individual hospitals (eg, differences in institutional admission/discharge practices) may help alleviate the weekend effect and improve healthcare quality.

Acknowledgments

This manuscript resulted from “Paper in a Day,” a Pediatric Research in Inpatient Settings (PRIS) Network-sponsored workshop presented at the Pediatric Hospital Medicine 2017 annual meeting. Workshop participants learned how to ask and answer a health services research question and efficiently prepare a manuscript for publication. The following are the members of the PRIS Network who contributed to this work: Jessica L. Bettenhausen, MD; Rebecca M. Cantu, MD, MPH; Jillian M Cotter, MD; Megan Deisz, MD; Teresa Frazer, MD; Pratichi Goenka, MD; Ashley Jenkins, MD; Kathryn E. Kyler, MD; Janet T. Lau, MD; Brian E. Lee, MD; Christiane Lenzen, MD; Trisha Marshall, MD; John M. Morrison MD, PhD; Lauren Nassetta, MD; Raymond Parlar-Chun, MD; Sonya Tang Girdwood MD, PhD; Tony R Tarchichi, MD; Irina G. Trifonova, MD; Jacqueline M. Walker, MD, MHPE; and Susan C. Walley, MD. See appendix for contact information for members of the PRIS Network

Funding

The authors have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Increasingly, metrics such as length of stay (LOS) and readmissions are being utilized in the United States to assess quality of healthcare because these factors may represent opportunities to reduce cost and improve healthcare delivery.1-8 However, the relatively low rate of pediatric readmissions,9 coupled with limited data regarding recommended LOS or best practices to prevent readmissions in children, challenges the ability of hospitals to safely reduce LOS and readmission rates for children.10–12

In adults, weekend admission is associated with prolonged LOS, increased readmission rates, and increased risk of mortality.13-21 This association is referred to as the “weekend effect.” While the weekend effect has been examined in children, the results of these studies have been variable, with some studies supporting this association and others refuting it.22-31 In contrast to patient demographic and clinical characteristics that are known to affect LOS and readmissions,32 the weekend effect represents a potentially modifiable aspect of a hospitalization that could be targeted to improve healthcare delivery.

With increasing national attention toward improving quality of care and reducing LOS and healthcare costs, more definitive evidence of the weekend effect is necessary to prioritize resource use at both the local and national levels. Therefore, we sought to determine the association of weekend admission and weekend discharge on LOS and 30-day readmissions, respectively, among a national cohort of children. We hypothesized that children admitted on the weekend would have longer LOS, whereas those discharged on the weekend would have higher readmission rates.

METHODS

Study Design and Data Source

We conducted a multicenter, retrospective, cross-sectional study. Data were obtained from the Pediatric Health Information System (PHIS), an administrative and billing database of 46 free-standing tertiary care pediatric hospitals affiliated with the Children’s Hospital Association (Lenexa, Kansas). Patient data are de-identified within PHIS; however, encrypted patient identifiers allow individual patients to be followed across visits. This study was not considered human subjects research by the policies of the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Institutional Review Board.

Participants

We included hospitalizations to a PHIS-participating hospital for children aged 0-17 years between October 1, 2014 and September 30, 2015. We excluded children who were transferred from/to another institution, left against medical advice, or died in the hospital because these indications may result in incomplete LOS information and would not consistently contribute to readmission rates. We also excluded birth hospitalizations and children admitted for planned procedures. Birth hospitalizations were defined as hospitalizations that began on the day of birth.

Main Exposures

No standard definition of weekend admission or discharge was identified in the literature.33 Thus, we defined a weekend admission as an admission between 3:00

Main Outcomes

Our outcomes included LOS for weekend admission and 30-day readmissions for weekend discharge. LOS, measured in hours, was defined using the reported admission and discharge times. Readmissions were defined as a return to the same hospital within the subsequent 30 days following discharge.

Patient Demographics and Other Study Variables

Patient demographics included age, gender, race/ethnicity, payer, and median household income quartile based on the patient’s home ZIP code. Other study variables included presence of a complex chronic condition (CCC),34 technology dependence,34 number of chronic conditions of any complexity, admission through the emergency department, intensive care unit (ICU) admission, and case mix index. ICU admission and case mix index were chosen as markers for severity of illness. ICU admission was defined as any child who incurred ICU charges at any time following admission. Case mix index in PHIS is a relative weight assigned to each discharge based on the All-Patient Refined Diagnostic Group (APR-DRG; 3M) assignment and APR-DRG severity of illness, which ranges from 1 (minor) to 4 (extreme). The weights are derived by the Children’s Hospital Association from the HCUP KID 2012 database as the ratio of the average cost for discharges within a specific APR-DRG severity of illness combination to the average cost for all discharges in the database.

Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables were summarized with medians and interquartile ranges, while categorical variables were summarized with frequencies and percentages. Differences in admission and discharge characteristics between weekend and weekday were assessed using Wilcoxon rank sum tests for continuous variables and chi-square tests of association for categorical variables. We used generalized linear mixed modeling (GLMM) techniques to assess the impact of weekend admission on LOS and weekend discharge on readmission, adjusting for important patient demographic and clinical characteristics. Furthermore, we used GLMM point estimates to describe the variation across hospitals of the impact of weekday versus weekend care on LOS and readmissions. We assumed an underlying log-normal distribution for LOS and an underlying binomial distribution for 30-day readmission. All GLMMs included a random intercept for each hospital to account for patient clustering within a hospital. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS v.9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina), and P values <.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

We identified 390,745 hospitalizations that met inclusion criteria (Supplementary Figure 1). The median LOS among our cohort was 41 hours (interquartile range [IQR] 24-71) and the median 30-day readmission rate was 8.2% (IQR 7.2-9.4).

Admission Demographics for Weekends and Weekdays

Among the included hospitalizations, 92,266 (23.6%) admissions occurred on a weekend (Supplementary Table 1). Overall, a higher percentage of children <5 years of age were admitted on a weekend compared with those admitted on a weekday (53.3% vs 49.1%, P < .001). We observed a small but statistically significant difference in the proportion of weekend versus weekday admissions according to gender, race/ethnicity, payer, and median household income quartile. Children with medical complexity and those with technology dependence were admitted less frequently on a weekend. A higher proportion of children were admitted through the emergency department on a weekend and a higher frequency of ICU utilization was observed for children admitted on a weekend compared with those admitted on a weekday.

Association Between Study Variables and Length of Stay

In comparing adjusted LOS for weekend versus weekday admissions across 43 hospitals, not only did LOS vary across hospitals (P < .001), but the association between LOS and weekend versus weekday care also varied across hospitals (P < .001) (Figure 1). Weekend admission was associated with a significantly longer LOS at eight (18.6%) hospitals and a significantly shorter LOS at four (9.3%) hospitals with nonstatistically significant differences at the remaining hospitals.

In adjusted analyses, we observed that infants ≤30 days of age, on average, had an adjusted LOS that was 24% longer than that of 15- to 17-year-olds, while children aged 1-14 years had an adjusted LOS that was 6%-18% shorter (Table 1). ICU utilization, admission through the emergency department, and number of chronic conditions had the greatest association with LOS. As the number of chronic conditions increased, the LOS increased. No association was found between weekend versus weekday admission and LOS (adjusted LOS [95% CI]: weekend 63.70 [61.01-66.52] hours versus weekday 63.40 [60.73-66.19] hours, P = .112).

Discharge Demographics for Weekends and Weekdays

Of the included hospitalizations, 127,421 (32.6%) discharges occurred on a weekend (Supplementary Table 2). Overall, a greater percentage of weekend discharges comprised children <5 years of age compared with the percentage of weekday discharges for children <5 years of age (51.5% vs 49.5%, P < .001). No statistically significant differences were found in gender, payer, or median household income quartile between those children discharged on a weekend versus those discharged on a weekday. We found small, statistically significant differences in the proportion of weekend versus weekday discharges according to race/ethnicity, with fewer non-Hispanic white children being discharged on the weekend versus weekday. Children with medical complexity, technology dependence, and patients with ICU utilization were less frequently discharged on a weekend compared with those discharged on a weekday.

Association Between Study Variables and Readmissions

In comparing the adjusted odds of readmissions for weekend versus weekday discharges across 43 PHIS hospitals, we observed significant variation (P < .001) in readmission rates from hospital to hospital (Figure 2). However, the direction of impact of weekend care on readmissions was similar (P = .314) across hospitals (ie, for 37 of 43 hospitals, the readmission rate was greater for weekend discharges compared with that for weekday discharges). For 17 (39.5%) of 43 hospitals, weekend discharge was associated with a significantly higher readmission rate, while the differences between weekday and weekend discharge were not statistically significant for the remaining hospitals.

In adjusted analyses, we observed that infants <1 year were more likely to be readmitted compared with 15- to 17-year-olds, while children 5-14 years of age were less likely to be readmitted (Table 2). Medical complexity and the number of chronic conditions had the greatest association with readmissions, with increased likelihood of readmission observed as the number of chronic conditions increased. Weekend discharge was associated with increased probability of readmission compared with weekday discharge (adjusted probability of readmission [95% CI]: weekend 0.13 [0.12-0.13] vs weekday 0.11 [0.11-0.12], P < .001).

DISCUSSION

While the reasons for the weekend effect are unclear, data supporting this difference have been observed across many diverse patient groups and health systems both nationally and internationally.13-27,31 Weekend care is thought to differ from weekday care because of differences in physician and nurse staffing, availability of ancillary services, access to diagnostic testing and therapeutic interventions, ability to arrange outpatient follow-up, and individual patient clinical factors, including acuity of illness. Few studies have assessed the effect of weekend discharges on patient or system outcomes. Among children within a single health system, readmission risk was associated with weekend admission but not with weekend discharge.22 This observation suggests that if differential care exists, then it occurs during initial clinical management rather than during discharge planning. Consequently, understanding the interaction of weekend admission and LOS is important. In addition, the relative paucity of pediatric data examining a weekend discharge effect limits the ability to generalize these findings across other hospitals or health systems.

In contrast to prior work, we observed a modest increased risk for readmission among those discharged on the weekend in a large sample of children. Auger and Davis reported a lack of association between weekend discharge and readmissions at one tertiary care children’s hospital, citing reduced discharge volumes on the weekend, especially among children with medical complexity, as a possible driver for their observation.22 The inclusion of a much larger population across 43 hospitals in our study may explain our different findings compared with previous research. In addition, the inclusion/exclusion criteria differed between the two studies; we excluded index admissions for planned procedures in this study (which are more likely to occur during the week), which may have contributed to the differing conclusions. Although Auger and Davis suggest that differences in initial clinical management may be responsible for the weekend effect,22 our observations suggest that discharge planning practices may also contribute to readmission risk. For example, a family’s inability to access compounded medications at a local pharmacy or to access primary care following discharge could reasonably contribute to treatment failure and increased readmission risk. Attention to improving and standardizing discharge practices may alleviate differences in readmission risk among children discharged on a weekend.

Individual patient characteristics greatly influence LOS and readmission risk. Congruent with prior studies, medical complexity and technology dependence were among the factors in our study that had the strongest association with LOS and readmission risk.32 As with prior studies22, we observed that children with medical complexity and technology dependence were less frequently admitted and discharged on a weekend than on a weekday, which suggests that physicians may avoid complicated discharges on the weekend. Children with medical complexity present a unique challenge to physicians when assessing discharge readiness, given that these children frequently require careful coordination of durable medical equipment, obtainment of special medication preparations, and possibly the resumption or establishment of home health services. Notably, we cannot discern from our data what proportion of discharges may be delayed over the weekend secondary to challenges involved in coordinating care for children with medical complexity. Future investigations aimed at assessing physician decision making and discharge readiness in relation to discharge timing among children with medical complexity may establish this relationship more clearly.

We observed substantial variation in LOS and readmission risk across 43 tertiary care children’s hospitals. Since the 1970s, numerous studies have reported worse outcomes among patients admitted on the weekend. While the majority of studies support the weekend effect, several recent studies suggest that patients admitted on the weekend are at no greater risk of adverse outcomes than those admitted during the week.35-37 Our work builds on the existing literature, demonstrating a complex and variable relationship between weekend admission/discharge, LOS, and readmission risk across hospitals. Notably, while many hospitals in our study experienced a significant weekend effect in LOS or readmission risk, only four hospitals experienced a statistically significant weekend effect for both LOS and readmission risk (three hospitals experienced increased risk for both, while one hospital experienced increased readmission risk but decreased LOS). Future investigations of the weekend effect should focus on exploring the differences in admission/discharge practices and staffing patterns of hospitals that did or did not experience a weekend effect.

This study has several limitations

CONCLUSION

In a study of 43 children’s hospitals, children discharged on the weekend had a slightly increased readmission risk compared with children discharged on a weekday. Wide variation in the weekend effect on LOS and readmission risk was evident across hospitals. Individual patient characteristics had a greater impact on LOS and readmission risk than the weekend effect. Future investigations aimed at understanding which factors contribute most strongly to a weekend effect within individual hospitals (eg, differences in institutional admission/discharge practices) may help alleviate the weekend effect and improve healthcare quality.

Acknowledgments

This manuscript resulted from “Paper in a Day,” a Pediatric Research in Inpatient Settings (PRIS) Network-sponsored workshop presented at the Pediatric Hospital Medicine 2017 annual meeting. Workshop participants learned how to ask and answer a health services research question and efficiently prepare a manuscript for publication. The following are the members of the PRIS Network who contributed to this work: Jessica L. Bettenhausen, MD; Rebecca M. Cantu, MD, MPH; Jillian M Cotter, MD; Megan Deisz, MD; Teresa Frazer, MD; Pratichi Goenka, MD; Ashley Jenkins, MD; Kathryn E. Kyler, MD; Janet T. Lau, MD; Brian E. Lee, MD; Christiane Lenzen, MD; Trisha Marshall, MD; John M. Morrison MD, PhD; Lauren Nassetta, MD; Raymond Parlar-Chun, MD; Sonya Tang Girdwood MD, PhD; Tony R Tarchichi, MD; Irina G. Trifonova, MD; Jacqueline M. Walker, MD, MHPE; and Susan C. Walley, MD. See appendix for contact information for members of the PRIS Network

Funding

The authors have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

1. Crossing the Quality Chasm: The IOM Health Care Quality Initiative : Health and Medicine Division. http://www.nationalacademies.org/hmd/Global/News%20Announcements/Crossing-the-Quality-Chasm-The-IOM-Health-Care-Quality-Initiative.aspx. Accessed November 20, 2017.

2. Institute for Healthcare Improvement: IHI Home Page. http://www.ihi.org:80/Pages/default.aspx. Accessed November 20, 2017.

3. Berry JG, Zaslavsky AM, Toomey SL, et al. Recognizing differences in hospital quality performance for pediatric inpatient care. Pediatrics. 2015;136(2):251-262. doi:10.1542/peds.2014-3131

4. NQF: All-Cause Admissions and Readmissions Measures - Final Report. http://www.qualityforum.org/Publications/2015/04/All-Cause_Admissions_and_Readmissions_Measures_-_Final_Report.aspx. Accessed March 24, 2018.

5. Hospital Inpatient Potentially Preventable Readmissions Information and Reports. https://www.illinois.gov/hfs/MedicalProviders/hospitals/PPRReports/Pages/default.aspx. Accessed November 6, 2016.

6. Potentially Preventable Readmissions in Texas Medicaid and CHIP Programs - Fiscal Year 2013 | Texas Health and Human Services. https://hhs.texas.gov/reports/2016/08/potentially-preventable-readmissions-texas-medicaid-and-chip-programs-fiscal-year. Accessed November 6, 2016.

7. Statewide Planning and Research Cooperative System. http://www.health.ny.gov/statistics/sparcs/sb/. Accessed November 6, 2016.

8. HCA Implements Potentially Preventable Readmission (PPR) Adjustments. Wash State Hosp Assoc. http://www.wsha.org/articles/hca-implements-potentially-preventable-readmission-ppr-adjustments/. Accessed November 8, 2016.

9. Berry JG, Toomey SL, Zaslavsky AM, et al. Pediatric readmission prevalence and variability across hospitals. JAMA. 2013;309(4):372-380. doi:10.1001/jama.2012.188351 PubMed

10. Bardach NS, Vittinghoff E, Asteria-Peñaloza R, et al. Measuring hospital quality using pediatric readmission and revisit rates. Pediatrics. 2013;132(3):429-436. doi:10.1542/peds.2012-3527 PubMed

11. Berry JG, Blaine K, Rogers J, et al. A framework of pediatric hospital discharge care informed by legislation, research, and practice. JAMA Pediatr. 2014;168(10):955-962; quiz 965-966. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.891 PubMed

12. Auger KA, Simon TD, Cooperberg D, et al. Summary of STARNet: seamless transitions and (Re)admissions network. Pediatrics. 2015;135(1):164. doi:10.1542/peds.2014-1887 PubMed

13. Freemantle N, Ray D, McNulty D, et al. Increased mortality associated with weekend hospital admission: a case for expanded seven day services? BMJ. 2015;351:h4596. doi:10.1136/bmj.h4596 PubMed

14. Schilling PL, Campbell DA, Englesbe MJ, Davis MM. A comparison of in-hospital mortality risk conferred by high hospital occupancy, differences in nurse staffing levels, weekend admission, and seasonal influenza. Med Care. 2010;48(3):224-232. doi:10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181c162c0 PubMed

15. Cram P, Hillis SL, Barnett M, Rosenthal GE. Effects of weekend admission and hospital teaching status on in-hospital mortality. Am J Med. 2004;117(3):151-157. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2004.02.035 PubMed

16. Zapf MAC, Kothari AN, Markossian T, et al. The “weekend effect” in urgent general operative procedures. Surgery. 2015;158(2):508-514. doi:10.1016/j.surg.2015.02.024 PubMed

17. Freemantle N, Richardson M, Wood J, et al. Weekend hospitalization and additional risk of death: an analysis of inpatient data. J R Soc Med. 2012;105(2):74-84. doi:10.1258/jrsm.2012.120009 PubMed

18. Bell CM, Redelmeier DA. Mortality among patients admitted to hospitals on weekends as compared with weekdays. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(9):663-668. doi:10.1056/NEJMsa003376 PubMed

19. Coiera E, Wang Y, Magrabi F, Concha OP, Gallego B, Runciman W. Predicting the cumulative risk of death during hospitalization by modeling weekend, weekday and diurnal mortality risks. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:226. doi:10.1186/1472-6963-14-226 PubMed

20. Powell ES, Khare RK, Courtney DM, Feinglass J. The weekend effect for patients with sepsis presenting to the emergency department. J Emerg Med. 2013;45(5):641-648. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2013.04.042 PubMed

21. Ananthakrishnan AN, McGinley EL, Saeian K. Outcomes of weekend admissions for upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage: a nationwide analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol Off Clin Pract J Am Gastroenterol Assoc. 2009;7(3):296-302e1. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2008.08.013 PubMed

22. Auger KA, Davis MM. Pediatric weekend admission and increased unplanned readmission rates. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(11):743-745. doi:10.1002/jhm.2426 PubMed

23. Goldstein SD, Papandria DJ, Aboagye J, et al. The “weekend effect” in pediatric surgery - increased mortality for children undergoing urgent surgery during the weekend. J Pediatr Surg. 2014;49(7):1087-1091. doi:10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2014.01.001 PubMed

24. Adil MM, Vidal G, Beslow LA. Weekend effect in children with stroke in the nationwide inpatient sample. Stroke. 2016;47(6):1436-1443. doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.116.013453 PubMed

25. McCrory MC, Spaeder MC, Gower EW, et al. Time of admission to the PICU and mortality. Pediatr Crit Care Med J Soc Crit Care Med World Fed Pediatr Intensive Crit Care Soc. 2017;18(10):915-923. doi:10.1097/PCC.0000000000001268 PubMed

26. Mangold WD. Neonatal mortality by the day of the week in the 1974-75 Arkansas live birth cohort. Am J Public Health. 1981;71(6):601-605. PubMed

27. MacFarlane A. Variations in number of births and perinatal mortality by day of week in England and Wales. Br Med J. 1978;2(6153):1670-1673. PubMed

28. McShane P, Draper ES, McKinney PA, McFadzean J, Parslow RC, Paediatric intensive care audit network (PICANet). Effects of out-of-hours and winter admissions and number of patients per unit on mortality in pediatric intensive care. J Pediatr. 2013;163(4):1039-1044.e5. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2013.03.061 PubMed

29. Hixson ED, Davis S, Morris S, Harrison AM. Do weekends or evenings matter in a pediatric intensive care unit? Pediatr Crit Care Med J Soc Crit Care Med World Fed Pediatr Intensive Crit Care Soc. 2005;6(5):523-530. PubMed

30. Gonzalez KW, Dalton BGA, Weaver KL, Sherman AK, St Peter SD, Snyder CL. Effect of timing of cannulation on outcome for pediatric extracorporeal life support. Pediatr Surg Int. 2016;32(7):665-669. doi:10.1007/s00383-016-3901-6 PubMed

31. Desai V, Gonda D, Ryan SL, et al. The effect of weekend and after-hours surgery on morbidity and mortality rates in pediatric neurosurgery patients. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2015;16(6):726-731. doi:10.3171/2015.6.PEDS15184 PubMed

32. Berry JG, Hall DE, Kuo DZ, et al. Hospital utilization and characteristics of patients experiencing recurrent readmissions within children’s hospitals. JAMA. 2011;305(7):682-690. doi:10.1001/jama.2011.122 PubMed

33. Hoshijima H, Takeuchi R, Mihara T, et al. Weekend versus weekday admission and short-term mortality: A meta-analysis of 88 cohort studies including 56,934,649 participants. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96(17):e6685. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000006685 PubMed

34. Feudtner C, Feinstein JA, Zhong W, Hall M, Dai D. Pediatric complex chronic conditions classification system version 2: updated for ICD-10 and complex medical technology dependence and transplantation. BMC Pediatr. 2014;14:199. doi:10.1186/1471-2431-14-199 PubMed

35. Li L, Rothwell PM, Oxford Vascular Study. Biases in detection of apparent “weekend effect” on outcome with administrative coding data: population based study of stroke. BMJ. 2016;353:i2648. doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.i2648 PubMed

36. Bray BD, Cloud GC, James MA, et al. Weekly variation in health-care quality by day and time of admission: a nationwide, registry-based, prospective cohort study of acute stroke care. The Lancet. 2016;388(10040):170-177. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30443-3 PubMed

37. Ko SQ, Strom JB, Shen C, Yeh RW. Mortality, Length of Stay, and Cost of Weekend Admissions. J Hosp Med. 2018. doi:10.12788/jhm.2906 PubMed

38. Tubbs-Cooley HL, Cimiotti JP, Silber JH, Sloane DM, Aiken LH. An observational study of nurse staffing ratios and hospital readmission among children admitted for common conditions. BMJ Qual Saf. 2013;22(9):735-742. doi:10.1136/bmjqs-2012-001610 PubMed

39. Ong M, Bostrom A, Vidyarthi A, McCulloch C, Auerbach A. House staff team workload and organization effects on patient outcomes in an academic general internal medicine inpatient service. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(1):47-52. doi:10.1001/archinte.167.1.47 PubMed

1. Crossing the Quality Chasm: The IOM Health Care Quality Initiative : Health and Medicine Division. http://www.nationalacademies.org/hmd/Global/News%20Announcements/Crossing-the-Quality-Chasm-The-IOM-Health-Care-Quality-Initiative.aspx. Accessed November 20, 2017.

2. Institute for Healthcare Improvement: IHI Home Page. http://www.ihi.org:80/Pages/default.aspx. Accessed November 20, 2017.

3. Berry JG, Zaslavsky AM, Toomey SL, et al. Recognizing differences in hospital quality performance for pediatric inpatient care. Pediatrics. 2015;136(2):251-262. doi:10.1542/peds.2014-3131

4. NQF: All-Cause Admissions and Readmissions Measures - Final Report. http://www.qualityforum.org/Publications/2015/04/All-Cause_Admissions_and_Readmissions_Measures_-_Final_Report.aspx. Accessed March 24, 2018.

5. Hospital Inpatient Potentially Preventable Readmissions Information and Reports. https://www.illinois.gov/hfs/MedicalProviders/hospitals/PPRReports/Pages/default.aspx. Accessed November 6, 2016.

6. Potentially Preventable Readmissions in Texas Medicaid and CHIP Programs - Fiscal Year 2013 | Texas Health and Human Services. https://hhs.texas.gov/reports/2016/08/potentially-preventable-readmissions-texas-medicaid-and-chip-programs-fiscal-year. Accessed November 6, 2016.

7. Statewide Planning and Research Cooperative System. http://www.health.ny.gov/statistics/sparcs/sb/. Accessed November 6, 2016.

8. HCA Implements Potentially Preventable Readmission (PPR) Adjustments. Wash State Hosp Assoc. http://www.wsha.org/articles/hca-implements-potentially-preventable-readmission-ppr-adjustments/. Accessed November 8, 2016.

9. Berry JG, Toomey SL, Zaslavsky AM, et al. Pediatric readmission prevalence and variability across hospitals. JAMA. 2013;309(4):372-380. doi:10.1001/jama.2012.188351 PubMed

10. Bardach NS, Vittinghoff E, Asteria-Peñaloza R, et al. Measuring hospital quality using pediatric readmission and revisit rates. Pediatrics. 2013;132(3):429-436. doi:10.1542/peds.2012-3527 PubMed

11. Berry JG, Blaine K, Rogers J, et al. A framework of pediatric hospital discharge care informed by legislation, research, and practice. JAMA Pediatr. 2014;168(10):955-962; quiz 965-966. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.891 PubMed

12. Auger KA, Simon TD, Cooperberg D, et al. Summary of STARNet: seamless transitions and (Re)admissions network. Pediatrics. 2015;135(1):164. doi:10.1542/peds.2014-1887 PubMed

13. Freemantle N, Ray D, McNulty D, et al. Increased mortality associated with weekend hospital admission: a case for expanded seven day services? BMJ. 2015;351:h4596. doi:10.1136/bmj.h4596 PubMed

14. Schilling PL, Campbell DA, Englesbe MJ, Davis MM. A comparison of in-hospital mortality risk conferred by high hospital occupancy, differences in nurse staffing levels, weekend admission, and seasonal influenza. Med Care. 2010;48(3):224-232. doi:10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181c162c0 PubMed

15. Cram P, Hillis SL, Barnett M, Rosenthal GE. Effects of weekend admission and hospital teaching status on in-hospital mortality. Am J Med. 2004;117(3):151-157. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2004.02.035 PubMed

16. Zapf MAC, Kothari AN, Markossian T, et al. The “weekend effect” in urgent general operative procedures. Surgery. 2015;158(2):508-514. doi:10.1016/j.surg.2015.02.024 PubMed

17. Freemantle N, Richardson M, Wood J, et al. Weekend hospitalization and additional risk of death: an analysis of inpatient data. J R Soc Med. 2012;105(2):74-84. doi:10.1258/jrsm.2012.120009 PubMed

18. Bell CM, Redelmeier DA. Mortality among patients admitted to hospitals on weekends as compared with weekdays. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(9):663-668. doi:10.1056/NEJMsa003376 PubMed

19. Coiera E, Wang Y, Magrabi F, Concha OP, Gallego B, Runciman W. Predicting the cumulative risk of death during hospitalization by modeling weekend, weekday and diurnal mortality risks. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:226. doi:10.1186/1472-6963-14-226 PubMed

20. Powell ES, Khare RK, Courtney DM, Feinglass J. The weekend effect for patients with sepsis presenting to the emergency department. J Emerg Med. 2013;45(5):641-648. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2013.04.042 PubMed

21. Ananthakrishnan AN, McGinley EL, Saeian K. Outcomes of weekend admissions for upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage: a nationwide analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol Off Clin Pract J Am Gastroenterol Assoc. 2009;7(3):296-302e1. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2008.08.013 PubMed

22. Auger KA, Davis MM. Pediatric weekend admission and increased unplanned readmission rates. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(11):743-745. doi:10.1002/jhm.2426 PubMed

23. Goldstein SD, Papandria DJ, Aboagye J, et al. The “weekend effect” in pediatric surgery - increased mortality for children undergoing urgent surgery during the weekend. J Pediatr Surg. 2014;49(7):1087-1091. doi:10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2014.01.001 PubMed

24. Adil MM, Vidal G, Beslow LA. Weekend effect in children with stroke in the nationwide inpatient sample. Stroke. 2016;47(6):1436-1443. doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.116.013453 PubMed

25. McCrory MC, Spaeder MC, Gower EW, et al. Time of admission to the PICU and mortality. Pediatr Crit Care Med J Soc Crit Care Med World Fed Pediatr Intensive Crit Care Soc. 2017;18(10):915-923. doi:10.1097/PCC.0000000000001268 PubMed

26. Mangold WD. Neonatal mortality by the day of the week in the 1974-75 Arkansas live birth cohort. Am J Public Health. 1981;71(6):601-605. PubMed

27. MacFarlane A. Variations in number of births and perinatal mortality by day of week in England and Wales. Br Med J. 1978;2(6153):1670-1673. PubMed

28. McShane P, Draper ES, McKinney PA, McFadzean J, Parslow RC, Paediatric intensive care audit network (PICANet). Effects of out-of-hours and winter admissions and number of patients per unit on mortality in pediatric intensive care. J Pediatr. 2013;163(4):1039-1044.e5. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2013.03.061 PubMed

29. Hixson ED, Davis S, Morris S, Harrison AM. Do weekends or evenings matter in a pediatric intensive care unit? Pediatr Crit Care Med J Soc Crit Care Med World Fed Pediatr Intensive Crit Care Soc. 2005;6(5):523-530. PubMed

30. Gonzalez KW, Dalton BGA, Weaver KL, Sherman AK, St Peter SD, Snyder CL. Effect of timing of cannulation on outcome for pediatric extracorporeal life support. Pediatr Surg Int. 2016;32(7):665-669. doi:10.1007/s00383-016-3901-6 PubMed

31. Desai V, Gonda D, Ryan SL, et al. The effect of weekend and after-hours surgery on morbidity and mortality rates in pediatric neurosurgery patients. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2015;16(6):726-731. doi:10.3171/2015.6.PEDS15184 PubMed

32. Berry JG, Hall DE, Kuo DZ, et al. Hospital utilization and characteristics of patients experiencing recurrent readmissions within children’s hospitals. JAMA. 2011;305(7):682-690. doi:10.1001/jama.2011.122 PubMed

33. Hoshijima H, Takeuchi R, Mihara T, et al. Weekend versus weekday admission and short-term mortality: A meta-analysis of 88 cohort studies including 56,934,649 participants. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96(17):e6685. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000006685 PubMed

34. Feudtner C, Feinstein JA, Zhong W, Hall M, Dai D. Pediatric complex chronic conditions classification system version 2: updated for ICD-10 and complex medical technology dependence and transplantation. BMC Pediatr. 2014;14:199. doi:10.1186/1471-2431-14-199 PubMed

35. Li L, Rothwell PM, Oxford Vascular Study. Biases in detection of apparent “weekend effect” on outcome with administrative coding data: population based study of stroke. BMJ. 2016;353:i2648. doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.i2648 PubMed

36. Bray BD, Cloud GC, James MA, et al. Weekly variation in health-care quality by day and time of admission: a nationwide, registry-based, prospective cohort study of acute stroke care. The Lancet. 2016;388(10040):170-177. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30443-3 PubMed

37. Ko SQ, Strom JB, Shen C, Yeh RW. Mortality, Length of Stay, and Cost of Weekend Admissions. J Hosp Med. 2018. doi:10.12788/jhm.2906 PubMed

38. Tubbs-Cooley HL, Cimiotti JP, Silber JH, Sloane DM, Aiken LH. An observational study of nurse staffing ratios and hospital readmission among children admitted for common conditions. BMJ Qual Saf. 2013;22(9):735-742. doi:10.1136/bmjqs-2012-001610 PubMed

39. Ong M, Bostrom A, Vidyarthi A, McCulloch C, Auerbach A. House staff team workload and organization effects on patient outcomes in an academic general internal medicine inpatient service. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(1):47-52. doi:10.1001/archinte.167.1.47 PubMed

© 2018 Society of Hospital Medicine

Prevalence of Staphylococcus aureus and Use of Antistaphylococcal Therapy in Children Hospitalized with Pneumonia

Although Staphylococcus aureus pneumonia is common in children with cystic fibrosis and those with healthcare-associated infections (eg, ventilator-associated pneumonia),1,2 S. aureus is an uncommon cause of community-acquired pneumonia in children. In recent years, concerns have arisen about the increasing frequency and severity of staphylococcal pneumonia, largely fueled by the emergence of community-associated methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA).3,4 Thus, therapy with clindamycin or vancomycin, both active against MRSA, has been recommended when S. aureus is suspected.5 Given the lack of rapid and sensitive approaches to the detection of the etiologies of pneumonia, antibiotic selection is most often empirical, contributing to overuse of anti-MRSA antibiotics. In addition, resistance against these antibiotics, especially clindamycin, has been increasing.6,7

A better understanding of the likelihood of staphylococcal pneumonia would help to optimize empirical antibiotic selection, allowing for judicious use of antistaphylococcal antibiotics, while also avoiding poor outcomes due to delays in effective treatment when S. aureus is present.8 Using data from a multicenter, population-based study of pneumonia hospitalizations in children, we sought to describe the prevalence, clinical characteristics, and in-hospital outcomes of staphylococcal pneumonia and the prevalence of antistaphylococcal antibiotic use.

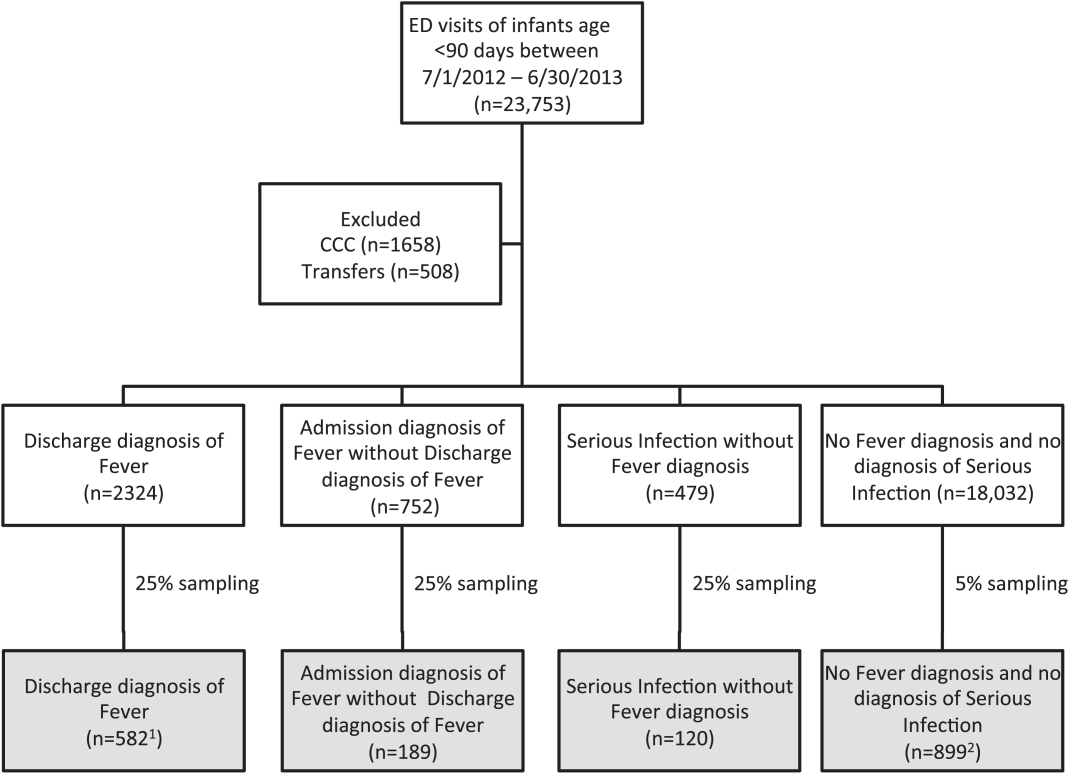

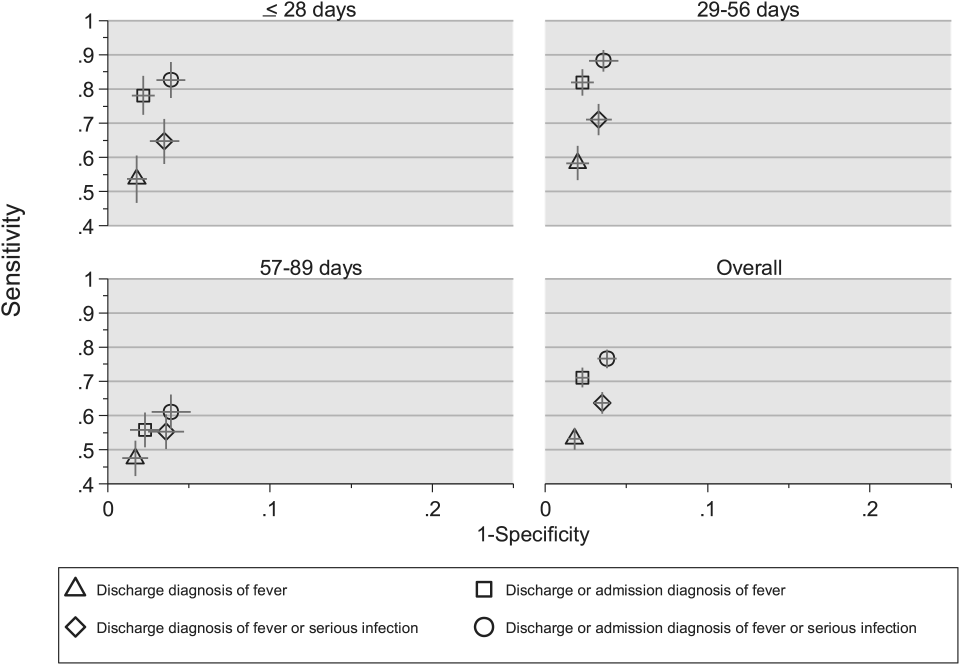

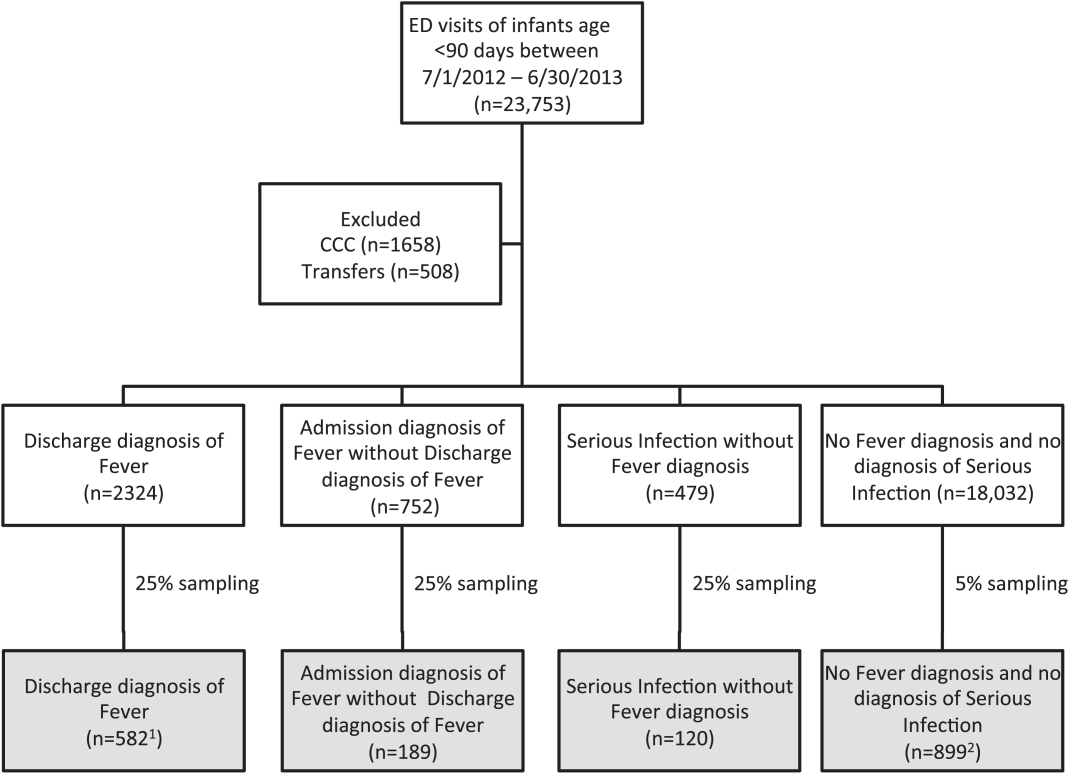

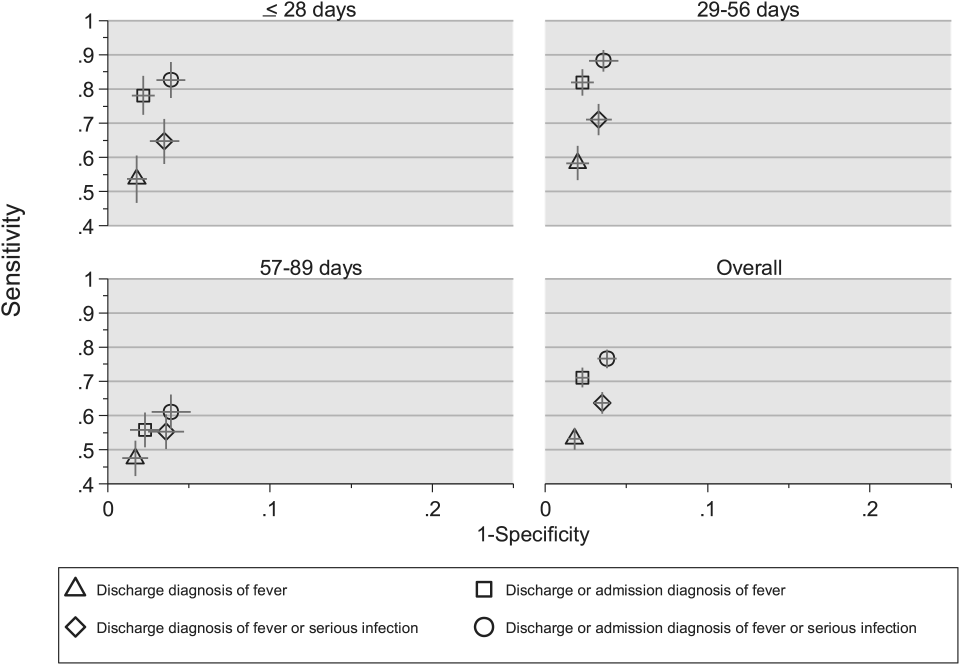

METHODS