User login

LOS in Children With Medical Complexity

Children with medical complexity (CMC) have complex and chronic health conditions that often involve multiple organ systems and severely affect cognitive and physical functioning. Although the prevalence of CMC is low (1% of all children), they account for nearly one‐fifth of all pediatric admissions and one‐half of all hospital days and charges in the United States.[1] Over the last decade, CMC have had a particularly large and increasing impact in tertiary‐care children's hospitals.[1, 2] The Institute of Medicine has identified CMC as a priority population for a revised healthcare system.[3]

Medical homes, hospitals, health plans, states, federal agencies, and others are striving to reduce excessive hospital use in CMC because of its high cost.[4, 5, 6] Containing length of stay (LOS)an increasingly used indicator of the time sensitiveness and efficiency of hospital careis a common aim across these initiatives. CMC have longer hospitalizations than children without medical complexity. Speculated reasons for this are that CMC tend to have (1) higher severity of acute illnesses (eg, pneumonia, cellulitis), (2) prolonged recovery time in the hospital, and (3) higher risk of adverse events in the hospital. Moreover, hospital clinicians caring for CMC often find it difficult to determine discharge readiness, given that many CMC do not return to a completely healthy baseline.[7]

Little is known about long LOS in CMC, including which CMC have the highest risk of experiencing such stays and which stays might have the greatest opportunity to be shortened. Patient characteristics associated with prolonged length of stay have been studied extensively for many pediatric conditions (eg, asthma).[8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14] However, most of these studies excluded CMC. Therefore, the objectives of this study were to examine (1) the prevalence of long LOS in CMC, (2) patient characteristics associated with long LOS, and (3) hospital‐to‐hospital variation in prevalence of long LOS hospitalizations.

METHODS

Study Design and Data Source

This study is a multicenter, retrospective cohort analysis of the Pediatric Health Information System (PHIS). PHIS is an administrative database of 44 not for profit, tertiary care pediatric hospitals affiliated with the Children's Hospital Association (CHA) (Overland Park, KS). PHIS contains data regarding patient demographics, diagnoses, and procedures (with International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification [ICD‐9‐CM] codes), All‐Patient Refined Diagnostic Related Groups version 30 (APR‐DRGs) (3M Health Information Systems, Salt Lake City, UT), and service lines that aggregate the APR‐DRGs into 38 distinct groups. Data quality and reliability are assured through CHA and participating hospitals. In accordance with the policies of the Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center Institutional Review Board, this study of deidentified data was not considered human subjects research.

Study Population

Inclusion Criteria

Children discharged following an observation or inpatient admission from a hospital participating in the PHIS database between January 1, 2013 and December 31, 2014 were eligible for inclusion if they were considered medically complex. Medical complexity was defined using Clinical Risk Groups (CRGs) version 1.8, developed by 3M Health Information Systems and the National Association of Children's Hospitals and Related Institutions. CRGs were used to assign each hospitalized patient to 1 of 9 mutually exclusive chronicity groups according to the presence, type, and severity of chronic conditions.[15, 16, 17, 18] Each patient's CRG designation was based on 2 years of previous hospital encounters.

As defined in prior studies and definitional frameworks of CMC,[1] patients belonging to CRG group 6 (significant chronic disease in 2 organ systems), CRG group 7 (dominant chronic disease in 3 organ systems), and CRG group 9 (catastrophic condition) were considered medically complex.[17, 19] Patients with malignancies (CRG group 8) were not included for analysis because they are a unique population with anticipated, long hospital stays. Patients with CRG group 5, representing those with chronic conditions affecting a single body system, were also not included because most do not have attributes consistent with medical complexity.

Exclusion Criteria

We used the APR‐DRG system, which leverages ICD‐9‐CM codes to identify the health problem most responsible for the hospitalization, to refine the study cohort. We excluded hospitalizations that were classified by the APR‐DRG system as neonatal, as we did not wish to focus on LOS in the neonatal intensive care unit (ICU) or for birth admissions. Similarly, hospitalizations for chemotherapy (APR‐DRG 693) or malignancy (identified with previously used ICD‐9‐CM codes)[20] were also excluded because long LOS is anticipated. We also excluded hospitalizations for medical rehabilitation (APR‐DRG 860).

Outcome Measures

The primary outcome measure was long LOS, defined as LOS 10 days. The cut point of LOS 10 days represents the 90th percentile of LOS for all children, with and without medical complexity, hospitalized during 2013 to 2014. LOS 10 days has previously been used as a threshold of long LOS.[21] For hospitalizations involving transfer at admission from another acute care facility, LOS was measured from the date of transfer. We also assessed hospitals' cost attributable to long LOS admissions.

Patient Demographics and Clinical Characteristics

We measured demographic characteristics including age, gender, race/ethnicity, insurance type, and distance traveled (the linear distance between the centroid of the patient's home ZIP code and the centroid of the hospital's ZIP code). Clinical characteristics included CRG classification, complex chronic condition (CCC), and dependence on medical technology. CCCs are defined as any medical condition that can be reasonably expected to last at least 12 months (unless death intervenes) and to involve either several different organ systems or 1 system severely enough to require specialty pediatric care and probably some period of hospitalization in a tertiary care center.[20] Medical technology included devices used to optimize the health and functioning of the child (eg, gastrostomy, tracheostomy, cerebrospinal fluid shunt).[22]

Hospitalization Characteristics

Characteristics of the hospitalization included transfer from an outside facility, ICU admission, surgical procedure (using surgical APR‐DRGs), and discharge disposition (home, skilled nursing facility, home health services, death, other). Cost of the hospitalization was estimated in the PHIS from charges using hospital and year‐specific ratios of cost to charge.

Statistical Analysis

Continuous data (eg, distance from hospital to home residence) were described with median and interquartile ranges (IQR) because they were not normally distributed. Categorical data (eg, type of chronic condition) were described with counts and frequencies. In bivariate analyses, demographic, clinical, and hospitalization characteristics were stratified by LOS (long LOS vs LOS <10 days), and compared using 2 statistics or Wilcoxon rank sum tests as appropriate.

We modeled the likelihood of experiencing a long LOS using generalized linear mixed effects models with a random hospital intercept and discharge‐level fixed effects for age, gender, payor, CCC type, ICU utilization, transfer status, a medical/surgical admission indicator derived from the APR‐DRG, and CRG assigned to each hospitalization. To examine hospital‐to‐hospital variability, we generated hospital risk‐adjusted rates of long LOS from these models. Similar models and hospital risk‐adjusted rates were built for a post hoc correlational analysis of 30‐day all cause readmission, where hospitals' rates and percent of long LOS were compared with a Pearson correlation coefficient. Also, for our multivariable models, we performed a sensitivity analysis using an alternative definition of long LOS as 4 days (the 75th percentile of LOS for all children, with and without medical complexity, hospitalized during 20132014). All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC), and P values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Study Population

There were 954,018 hospitalizations of 217,163 CMC at 44 children's hospitals included for analysis. Forty‐seven percent of hospitalizations were for females, 49.4% for non‐Hispanic whites, and 61.1% for children with government insurance. Fifteen percent (n = 142,082) had a long LOS of 10 days. The median (IQR) LOS of hospitalizations <10 days versus 10 days were 2 (IQR, 14) and 16 days (IQR, 1226), respectively. Long LOS hospitalizations accounted for 61.1% (3.7 million) hospital days and 61.8% ($13.7 billion) of total hospitalization costs for all CMC in the cohort (Table 1).

| Characteristic | Overall (n = 954,018) | Length of Stay | |

|---|---|---|---|

| <10 Days (n = 811,936) | 10 Days (n = 142,082) | ||

| |||

| Age at admission, y, % | |||

| <1 | 14.6 | 12.7 | 25.7 |

| 14 | 27.1 | 27.9 | 22.4 |

| 59 | 20.1 | 21.0 | 14.9 |

| 1018 | 33.6 | 34.0 | 31.7 |

| 18+ | 4.6 | 4.4 | 5.4 |

| Gender, % | |||

| Female | 47.0 | 46.9 | 47.5 |

| Race/ethnicity, % | |||

| Non‐Hispanic white | 49.4 | 49.4 | 49.4 |

| Non‐Hispanic black | 23.1 | 23.8 | 19.3 |

| Hispanic | 18.2 | 17.8 | 20.4 |

| Asian | 2.0 | 1.9 | 2.3 |

| Other | 7.4 | 7.1 | 8.6 |

| Complex chronic condition, % | |||

| Any | 79.5 | 77.3 | 91.8 |

| Technology assistance | 37.1 | 34.1 | 54.2 |

| Gastrointestinal | 30.0 | 27.2 | 45.9 |

| Neuromuscular | 28.2 | 27.7 | 30.9 |

| Cardiovascular | 16.8 | 14.5 | 29.9 |

| Respiratory | 14.1 | 11.5 | 29.4 |

| Congenital/genetic defect | 17.2 | 16.7 | 20.2 |

| Metabolic | 9.9 | 8.9 | 15.4 |

| Renal | 10.1 | 9.5 | 13.8 |

| Hematology/emmmunodeficiency | 11.7 | 12.0 | 10.0 |

| Neonatal | 3.8 | 3.1 | 7.7 |

| Transplantation | 4.5 | 4.2 | 6.7 |

| Clinical risk group, % | |||

| Chronic condition in 2 systems | 68.4 | 71.2 | 53.9 |

| Catastrophic chronic condition | 31.4 | 28.8 | 46.1 |

| Distance from hospital to home residence in miles, median [IQR] | 16.2 [7.440.4] | 15.8 [7.338.7] | 19.1 [8.552.6] |

| Transferred from outside hospital (%) | 6.5 | 5.3 | 13.6 |

| Admitted for surgery, % | 23.4 | 20.7 | 38.7 |

| Use of intensive care, % | 19.6 | 14.9 | 46.5 |

| Discharge disposition, % | |||

| Home | 91.2 | 92.9 | 81.4 |

| Home healthcare | 4.5 | 3.5 | 9.9 |

| Other | 2.9 | 2.6 | 4.5 |

| Postacute care facility | 1.1 | 0.8 | 3.1 |

| Died | 0.4 | 0.3 | 1.1 |

| Payor, % | |||

| Government | 61.1 | 60.6 | 63.5 |

| Private | 33.2 | 33.6 | 30.9 |

| Other | 5.7 | 5.7 | 5.7 |

| Hospital resource use | |||

| Median length of stay [IQR] | 3 [16] | 2 [14] | 16 [1226] |

| Median hospital cost [IQR] | $8,144 [$4,122$18,447] | $6,689 [$3,685$12,395] | $49,207 [$29,444$95,738] |

| Total hospital cost, $, billions | $22.2 | $8.5 | $13.7 |

Demographics and Clinical Characteristics of Children With and Without Long LOS

Compared with hospitalized CMC with LOS <10 days, a higher percentage of hospitalizations with LOS 10 days were CMC age <1 year (25.7% vs 12.7%, P < 0.001) and Hispanic (20.4% vs 17.8%, P < 0.001). CMC hospitalizations with a long LOS had a higher percentage of any CCC (91.8% vs 77.3%, P < 0.001); the most common CCCs were gastrointestinal (45.9%), neuromuscular (30.9%), and cardiovascular (29.9%). Hospitalizations of CMC with a long LOS had a higher percentage of a catastrophic chronic condition (46.1% vs 28.8%, P < 0.001) and technology dependence (46.1% vs 28.8%, P < 0.001) (Table 1).

Hospitalization Characteristics of Children With and Without Long LOS

Compared with hospitalizations of CMC with LOS <10 days, hospitalizations of CMC with a long LOS more often involved transfer in from another hospital at admission (13.6% vs 5.3%, P < 0.001). CMC hospital stays with a long LOS more often involved surgery (38.7% vs 20.7%, P < 0.001) and use of intensive care (46.5% vs 14.9%; P < 0.001). A higher percentage of CMC with long LOS were discharged with home health services (9.9% vs 3.5%; P < 0.001) (Table 1).

The most common admitting diagnoses and CCCs for hospitalizations of CMC with long LOS are presented in Table 2. The two most prevalent APR‐DRGs in CMC hospitalizations lasting 10 days or longer were cystic fibrosis (10.7%) and respiratory system disease with ventilator support (5.5%). The two most common chronic condition characteristics represented among long CMC hospitalizations were gastrointestinal devices (eg, gastrostomy tube) (39.7%) and heart and great vessel malformations (eg, tetralogy of Fallot) (12.8%). The 5 most common CCC subcategories, as listed in Table 2, account for nearly 100% of the patients with long LOS hospitalizations.

| |

| Most common reason for admission* | |

| Cystic fibrosis | 10.7% |

| Respiratory system diagnosis with ventilator support 96+ hours | 5.5% |

| Malfunction, reaction, and complication of cardiac or vascular device or procedure | 2.8% |

| Craniotomy except for trauma | 2.6% |

| Major small and large bowel procedures | 2.3% |

| Most common complex chronic condition | |

| Gastrointestinal devices | 39.7% |

| Heart and great vessel malformations | 12.8% |

| Cystic fibrosis | 12.5% |

| Dysrhythmias | 11.0% |

| Respiratory devices | 10.7% |

Multivariable Analysis of Characteristics Associated With Long LOS

In multivariable analysis, the highest likelihood of long LOS was experienced by children who received care in the ICU (odds ratio [OR]: 3.5, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 3.43.5), who had a respiratory CCC (OR: 2.7, 95% CI: 2.62.7), and who were transferred from another acute care hospital at admission (OR: 2.1, 95% CI: 2.0, 2.1). The likelihood of long LOS was also higher in children <1 year of age (OR: 1.2, 95% CI: 1.21.3), and Hispanic children (OR: 1.1, 95% CI 1.0‐1.10) (Table 3). Similar multivariable findings were observed in sensitivity analysis using the 75th percentile of LOS (4 days) as the model outcome.

| Characteristic | Odds Ratio (95% CI) of LOS 10 Days | P Value |

|---|---|---|

| ||

| Use of intensive care | 3.5 (3.4‐3.5) | <0.001 |

| Transfer from another acute‐care hospital | 2.1 (2.0‐2.1) | <0.001 |

| Procedure/surgery | 1.8 (1.8‐1.9) | <0.001 |

| Complex chronic condition | ||

| Respiratory | 2.7 (2.6‐2.7) | <0.001 |

| Gastrointestinal | 1.8 (1.8‐1.8) | <0.001 |

| Metabolic | 1.7 (1.7‐1.7) | <0.001 |

| Cardiovascular | 1.6 (1.5‐1.6) | <0.001 |

| Neonatal | 1.5 (1.5‐1.5) | <0.001 |

| Renal | 1.4 (1.4‐1.4) | <0.001 |

| Transplant | 1.4 (1.4‐1.4) | <0.001 |

| Hematology and immunodeficiency | 1.3 (1.3‐1.3) | <0.001 |

| Technology assistance | 1.1 (1.1, 1.1) | <0.001 |

| Neuromuscular | 0.9 (0.9‐0.9) | <0.001 |

| Congenital or genetic defect | 0.8 (0.8‐0.8) | <0.001 |

| Age at admission, y | ||

| <1 | 1.2 (1.2‐1.3) | <0.001 |

| 14 | 0.5 (0.5‐0.5) | <0.001 |

| 59 | 0.6 (0.6‐0.6) | <0.001 |

| 1018 | 0.9 (0.9‐0.9) | <0.001 |

| 18+ | Reference | |

| Male | 0.9 (0.9‐0.9) | <0.001 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| Non‐Hispanic black | 0.9 (0.9‐0.9) | <0.001 |

| Hispanic | 1.1 (1.0‐1.1) | <0.001 |

| Asian | 1.0 (1.0‐1.1) | 0.3 |

| Other | 1.1 (1.1‐1.1) | <0.001 |

| Non‐Hispanic white | Reference | |

| Payor | ||

| Private | 0.9 (0.8 0.9) | <0.001 |

| Other | 1.0 (1.0‐1.0) | 0.4 |

| Government | Reference | |

| Season | ||

| Spring | 1.0 (1.0 1.0) | <0.001 |

| Summer | 0.9 (0.9‐0.9) | <0.001 |

| Fall | 1.0 (0.9‐1.0) | <0.001 |

| Winter | Reference | |

Variation in the Prevalence of Long LOS Across Children's Hospitals

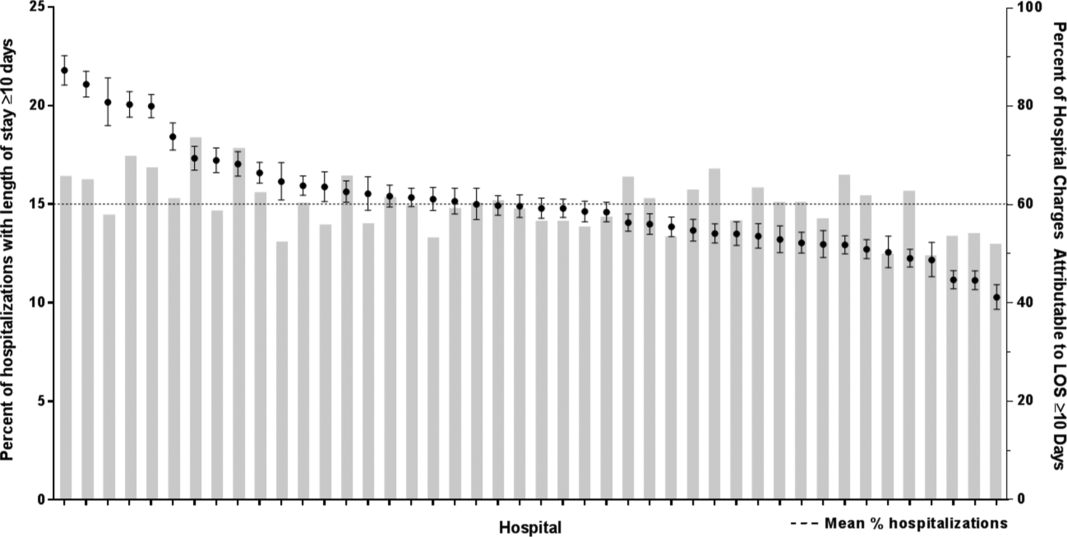

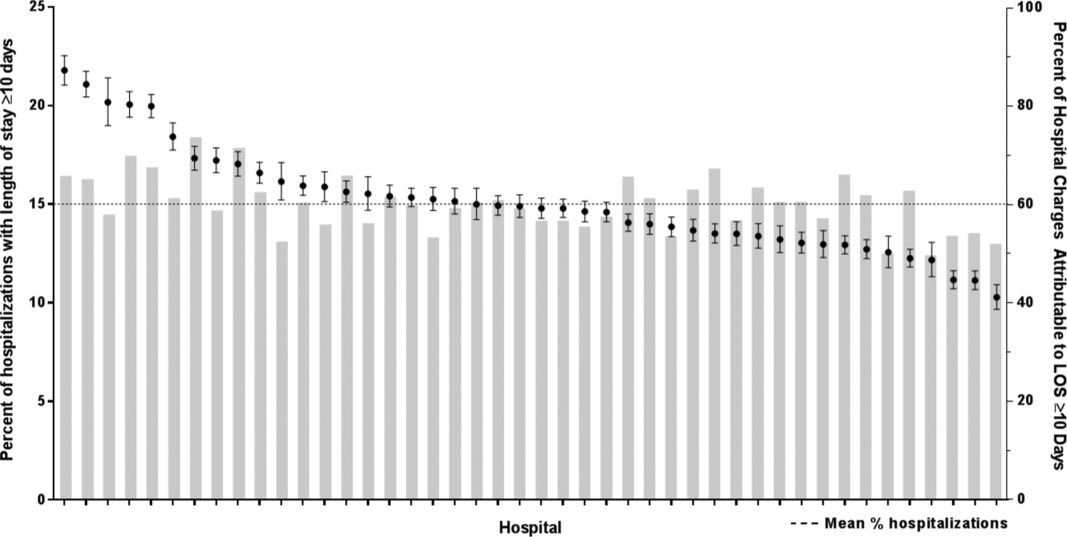

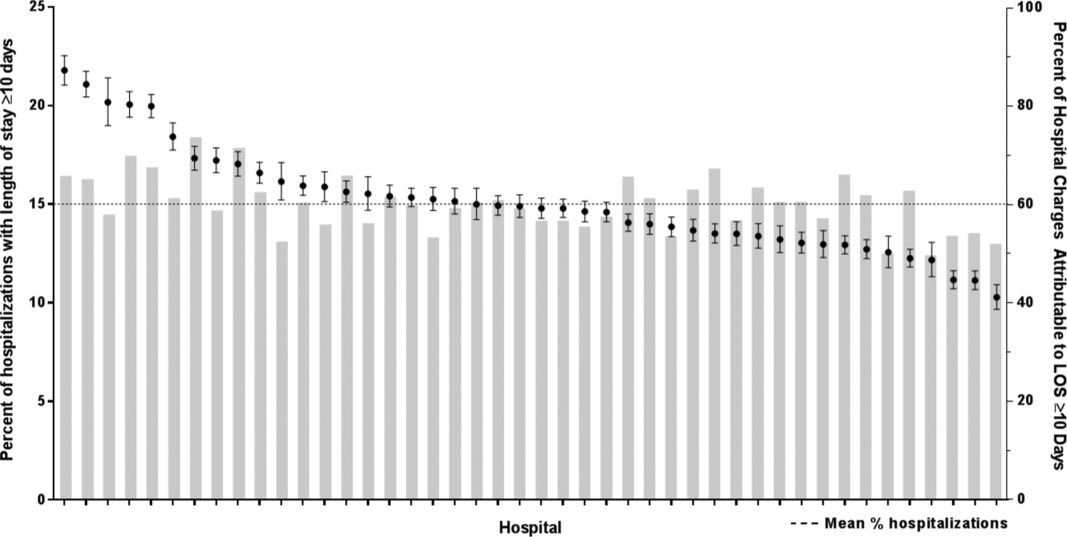

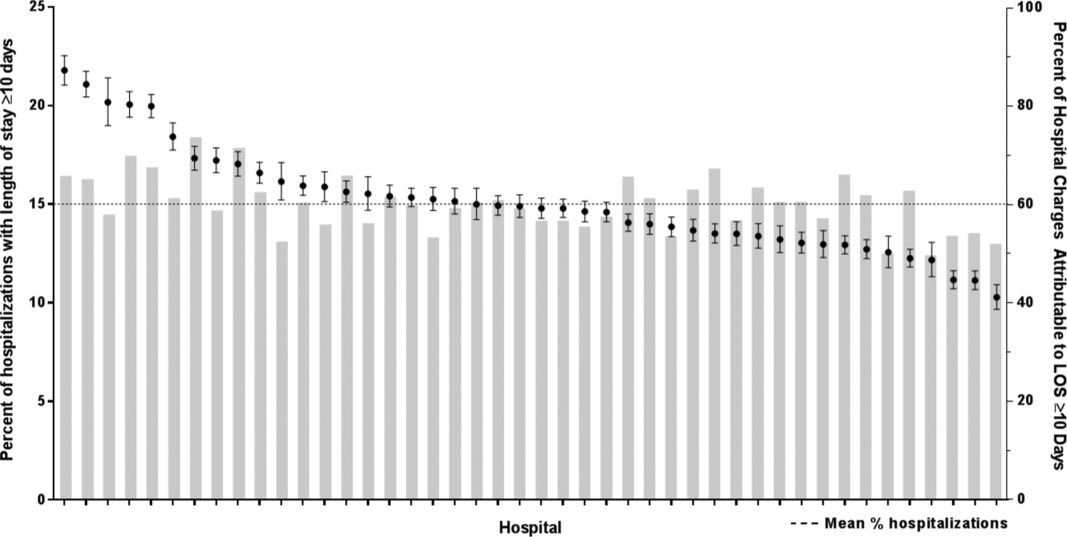

After controlling for demographic, clinical, and hospital characteristics associated with long LOS, there was significant (P < 0.001) variation in the prevalence of long LOS for CMC across children's hospitals in the cohort (range, 10.3%21.8%) (Figure 1). Twelve (27%) hospitals had a significantly (P < 0.001) higher prevalence of long LOS for their hospitalized CMC, compared to the mean. Eighteen (41%) had a significantly (P < 0.001) lower prevalence of long LOS for their hospitalized CMC. There was also significant variation across hospitals with respect to cost, with 49.7% to 73.7% of all hospital costs of CMC attributed to long LOS hospitalizations. Finally, there was indirect correlation with the prevalence of LOS across hospitals and the hospitals' 30‐day readmission rate ( = 0.3; P = 0.04). As the prevalence of long LOS increased, the readmission rate decreased.

DISCUSSION

The main findings from this study suggest that a small percentage of CMC experiencing long LOS account for the majority of hospital bed days and cost of all hospitalized CMC in children's hospitals. The likelihood of long LOS varies significantly by CMC's age, race/ethnicity, and payor as well as by type and number of chronic conditions. Among CMC with long LOS, the use of gastrointestinal devices such as gastrostomy tubes, as well as congenital heart disease, were highly prevalent. In multivariable analysis, the characteristics most strongly associated with LOS 10 days were use of the ICU, respiratory complex chronic condition, and transfer from another medical facility at admission. After adjusting for these factors, there was significant variation in the prevalence of LOS 10 days for CMC across children's hospitals.

Although it is well known that CMC as a whole have a major impact on resource use in children's hospitals, this study reveals that 15% of hospitalizations of CMC account for 62% of all hospital costs of CMC. That is, a small fraction of hospitalizations of CMC is largely responsible for the significant financial impact of hospital resource use. To date, most clinical efforts and policies striving to reduce hospital use in CMC have focused on avoiding readmissions or index hospital admissions entirely, rather than improving the efficiency of hospital care after admission occurs.[23, 24, 25, 26] In the adult population, the impact of long LOS on hospital costs has been recognized, and several Medicare incentive programs have focused on in‐hospital timeliness and efficiency. As a result, LOS in Medicare beneficiaries has decreased dramatically over the past 2 decades.[27, 28, 29, 30] Optimizing the efficiency of hospital care for CMC may be an important goal to pursue, especially with precedent set in the adult literature.

Perhaps the substantial variation across hospitals in the prevalence of long LOS in CMC indicates opportunity to improve the efficiency of their inpatient care. This variation was not due to differences across hospitals' case mix of CMC. Further investigation is needed to determine how much of it is due to differences in quality of care. Clinical practice guidelines for hospital treatment of common illnesses usually exclude CMC. In our clinical experience across 9 children's hospitals, we have experienced varying approaches to setting discharge goals (ie, parameters on how healthy the child needs to be to ensure a successful hospital discharge) for CMC.[31] When the goals are absent or not clearly articulated, they can contribute to a prolonged hospitalization. Some families of CMC report significant issues when working with pediatric hospital staff to assess their child's discharge readiness.[7, 32, 33] In addition, there is significant variation across states and regions in access to and quality of post‐discharge health services (eg, home nursing, postacute care, durable medical equipment).[34, 35] In some areas, many CMC are not actively involved with their primary care physician.[5] These issues might also influence the ability of some children's hospitals to efficiently discharge CMC to a safe and supportive post‐discharge environment. Further examination of hospital outliersthose with the lowest and highest percentage of CMC hospitalizations with long LOSmay reveal opportunities to identify and spread best practices.

The demographic and clinical factors associated with long LOS in the present study, including age, ICU use, and transfer from another hospital, might help hospitals target which CMC have the greatest risk for experiencing long LOS. We found that infants age <1 year had longer LOS when compared with older children. Similar to our findings, younger‐aged children hospitalized with bronchiolitis have longer LOS.[36] Certainly, infants with medical complexity, in general, are a high‐acuity population with the potential for rapid clinical deterioration during an acute illness. Prolonged hospitalization for treatment and stabilization may be expected for many of them. Additional investigation is warranted to examine ICU use in CMC, and whether ICU admission or duration can be safely prevented or abbreviated. Opportunities to assess the quality of transfers into children's hospitals of CMC admitted to outside hospitals may be necessary. A study of pediatric burn patients reported that patients initially stabilized at a facility that was not a burn center and subsequently transferred to a burn center had a longer LOS than patients solely treated at a designated burn center.[37] Furthermore, events during transport itself may adversely impact the stability of an already fragile patient. Interventions to optimize the quality of care provided by transport teams have resulted in decreased LOS at the receiving hospital.[38]

This study's findings should be considered in the context of several limitations. Absent a gold‐standard definition of long LOS, we used the distribution of LOS across patients to inform our methods; LOS at the 90th percentile was selected as long. Although our sensitivity analysis using LOS at the 75th percentile produced similar findings, other cut points in LOS might be associated with different results. The study is not positioned to determine how much of the reported LOS was excessive, unnecessary, or preventable. The study findings may not generalize to types of hospitals not contained in PHIS (eg, nonchildren's hospitals and community hospitals). We did not focus on the impact of a new diagnosis (eg, new chronic illness) or acute in‐hospital event (eg, nosocomial infection) on prolonged LOS; future studies should investigate these clinical events with LOS.

PHIS does not contain information regarding characteristics that could influence LOS, including the children's social and familial attributes, transportation availability, home equipment needs, and local availability of postacute care facilities. Moreover, PHIS does not contain information about the hospital discharge procedures, process, or personnel across hospitals, which could influence LOS. Future studies on prolonged LOS should consider assessing this information. Because of the large sample size of hospitalizations included, the statistical power for the analyses was strong, rendering it possible that some findings that were statistically significant might have modest clinical significance (eg, relationship of Hispanic ethnicity with prolonged LOS). We could not determine why a positive correlation was not observed between hospitals' long LOS prevalence and their percentage of cost associated with long LOS; future studies should investigate the reasons for this finding.

Despite these limitations, the findings of the present study highlight the significance of long LOS in hospitalized CMC. These long hospitalizations account for a significant proportion of all hospital costs for this important population of children. The prevalence of long LOS for CMC varies considerably across children's hospitals, even after accounting for the case mix. Efforts to curtail hospital resource use and costs for CMC may benefit from focus on long LOS.

- , , , et al. Inpatient growth and resource use in 28 children's hospitals: a longitudinal, multi‐institutional study. JAMA Pediatr. 2013;167(2):170–177.

- , , , et al. Children with complex chronic conditions in inpatient hospital settings in the united states. Pediatrics. 2010;126(4):647–655.

- , . Meeting the health care needs of persons with disabilities. Milbank Q. 2002;80(2):381–391.

- , , , et al. Effect of an enhanced medical home on serious illness and cost of care among high‐risk children with chronic illness: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014;312(24):2640–2648.

- , , , et al. Children with medical complexity and Medicaid: spending and cost savings. Health Aff Proj Hope. 2014;33(12):2199–2206.

- Children's Hospital Association. CARE Award. Available at: https://www.childrenshospitals.org/Programs‐and‐Services/Quality‐Improvement‐and‐Measurement/CARE‐Award. Accessed December 18, 2015.

- , , , et al. Hospital readmission and parent perceptions of their child's hospital discharge. Int J Qual Health Care. 2013;25(5):573–581.

- , , , et al. Weekend matters: Friday and Saturday admissions are associated with prolonged hospitalization of children. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2013;52(9):875–878.

- , , , . Attributable cost and length of stay for central line‐associated bloodstream infections. Pediatrics. 2014;133(6):e1525–e1532.

- , , , et al. Effect of healthcare‐acquired infection on length of hospital stay and cost. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2007;28(3):280–292.

- , , , , . Hospital utilization and costs among children with influenza, 2003. Am J Prev Med. 2009;36(4):292–296.

- , , , . Charges and lengths of stay attributable to adverse patient‐care events using pediatric‐specific quality indicators: a multicenter study of freestanding children's hospitals. Pediatrics. 2008;121(6):e1653–e1659.

- , , , , . Variation in resource utilization for the management of uncomplicated community‐acquired pneumonia across community and children's hospitals. J Pediatr. 2014;165(3):585–591.

- , , , , . Variation and outcomes associated with direct hospital admission among children with pneumonia in the United States. JAMA Pediatr. 2014;168(9):829–836.

- , , , et al. Clinical Risk Groups (CRGs): a classification system for risk‐adjusted capitation‐based payment and health care management. Med Care. 2004;42(1):81–90.

- , , , et al. Identifying children with lifelong chronic conditions for care coordination by using hospital discharge data. Acad Pediatr. 2010;10(6):417–423.

- , , , , . Profile of medical charges for children by health status group and severity level in a Washington State Health Plan. Health Serv Res. 2004;39(1):73–89.

- , , , . Using medical billing data to evaluate chronically ill children over time. J Ambulatory Care Manage. 2006;29(4):283–290.

- , , , , , . Medical complexity and pediatric emergency department and inpatient utilization. Pediatrics. 2013;131(2):e559–e565.

- , , , , . Pediatric complex chronic conditions classification system version 2: updated for ICD‐10 and complex medical technology dependence and transplantation. BMC Pediatr. 2014;14:199.

- . Analyzing intensive care unit length of stay data: problems and possible solutions. Crit Care Med. 1997;25(9):1594–1600.

- , , , et al. Hospital utilization and characteristics of patients experiencing recurrent readmissions within children's hospitals. JAMA. 2011;305(7):682–690.

- . Hospital readmissions and repeat emergency department visits among children with medical complexity: an integrative review. J Pediatr Nurs. 2013;28(4):316–339.

- , , , . Hospital readmission in children with complex chronic conditions discharged from subacute care. Hosp Pediatr. 2014;4(3):153–158.

- , , , et al. Preventing hospitalizations in children with medical complexity: a systematic review. Pediatrics. 2014;134(6):e1628–e1647.

- , , , . Hospital readmissions for newly discharged pediatric home mechanical ventilation patients. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2012;47(4):409–414.

- , , , et al. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of Medicare patients undergoing total hip arthroplasty, 1991–2008. JAMA. 2011;305(15):1560–1567.

- , , , et al. Trends in length of stay and short‐term outcomes among Medicare patients hospitalized for heart failure, 1993–2006. JAMA. 2010;303(21):2141–2147.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. CMS Statistics 2013. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/Research‐Statistics‐Data‐and‐Systems/Statistics‐Trends‐and‐Reports/CMS‐Statistics‐Reference‐Booklet/Downloads/CMS_Stats_2013_final.pdf. Published August 2013. Accessed October 6, 2015.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Evaluation of the premier hospital quality incentive demonstration. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/Research‐Statistics‐Data‐and‐Systems/Statistics‐Trends‐and‐Reports/Reports/downloads/Premier_ExecSum_2010.pdf. Published March 3, 2009. Accessed September 18, 2015.

- , , , et al. A framework of pediatric hospital discharge care informed by legislation, research, and practice. JAMA Pediatr. 2014;168(10):955–962; quiz 965–966.

- , , , , . Parent and provider perspectives on pediatric readmissions: what can we learn about readiness for discharge? Hosp Pediatr. 2015;5(11):559–565.

- , . Preventing readmissions in children: how do we do that? Hosp Pediatr. 2015;5(11):602–604.

- , , . Pediatric post‐acute hospital care: striving for identity and value. Hosp Pediatr. 2015;5(10):548–551.

- , , , et al. Pediatric hospital discharges to home health and postacute facility care: a national study. JAMA Pediatr. 2016;170(4):326–333.

- , , , et al. Bronchiolitis: clinical characteristics associated with hospitalization and length of stay. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2012;28(2):99–103.

- , , , , . The effect of transfers between health care facilities on costs and length of stay for pediatric burn patients. J Burn Care Res. 2015;36(1):178–183.

- , , , et al. Goal‐directed resuscitative interventions during pediatric interfacility transport. Crit Care Med. 2015;43(8):1692–1698.

Children with medical complexity (CMC) have complex and chronic health conditions that often involve multiple organ systems and severely affect cognitive and physical functioning. Although the prevalence of CMC is low (1% of all children), they account for nearly one‐fifth of all pediatric admissions and one‐half of all hospital days and charges in the United States.[1] Over the last decade, CMC have had a particularly large and increasing impact in tertiary‐care children's hospitals.[1, 2] The Institute of Medicine has identified CMC as a priority population for a revised healthcare system.[3]

Medical homes, hospitals, health plans, states, federal agencies, and others are striving to reduce excessive hospital use in CMC because of its high cost.[4, 5, 6] Containing length of stay (LOS)an increasingly used indicator of the time sensitiveness and efficiency of hospital careis a common aim across these initiatives. CMC have longer hospitalizations than children without medical complexity. Speculated reasons for this are that CMC tend to have (1) higher severity of acute illnesses (eg, pneumonia, cellulitis), (2) prolonged recovery time in the hospital, and (3) higher risk of adverse events in the hospital. Moreover, hospital clinicians caring for CMC often find it difficult to determine discharge readiness, given that many CMC do not return to a completely healthy baseline.[7]

Little is known about long LOS in CMC, including which CMC have the highest risk of experiencing such stays and which stays might have the greatest opportunity to be shortened. Patient characteristics associated with prolonged length of stay have been studied extensively for many pediatric conditions (eg, asthma).[8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14] However, most of these studies excluded CMC. Therefore, the objectives of this study were to examine (1) the prevalence of long LOS in CMC, (2) patient characteristics associated with long LOS, and (3) hospital‐to‐hospital variation in prevalence of long LOS hospitalizations.

METHODS

Study Design and Data Source

This study is a multicenter, retrospective cohort analysis of the Pediatric Health Information System (PHIS). PHIS is an administrative database of 44 not for profit, tertiary care pediatric hospitals affiliated with the Children's Hospital Association (CHA) (Overland Park, KS). PHIS contains data regarding patient demographics, diagnoses, and procedures (with International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification [ICD‐9‐CM] codes), All‐Patient Refined Diagnostic Related Groups version 30 (APR‐DRGs) (3M Health Information Systems, Salt Lake City, UT), and service lines that aggregate the APR‐DRGs into 38 distinct groups. Data quality and reliability are assured through CHA and participating hospitals. In accordance with the policies of the Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center Institutional Review Board, this study of deidentified data was not considered human subjects research.

Study Population

Inclusion Criteria

Children discharged following an observation or inpatient admission from a hospital participating in the PHIS database between January 1, 2013 and December 31, 2014 were eligible for inclusion if they were considered medically complex. Medical complexity was defined using Clinical Risk Groups (CRGs) version 1.8, developed by 3M Health Information Systems and the National Association of Children's Hospitals and Related Institutions. CRGs were used to assign each hospitalized patient to 1 of 9 mutually exclusive chronicity groups according to the presence, type, and severity of chronic conditions.[15, 16, 17, 18] Each patient's CRG designation was based on 2 years of previous hospital encounters.

As defined in prior studies and definitional frameworks of CMC,[1] patients belonging to CRG group 6 (significant chronic disease in 2 organ systems), CRG group 7 (dominant chronic disease in 3 organ systems), and CRG group 9 (catastrophic condition) were considered medically complex.[17, 19] Patients with malignancies (CRG group 8) were not included for analysis because they are a unique population with anticipated, long hospital stays. Patients with CRG group 5, representing those with chronic conditions affecting a single body system, were also not included because most do not have attributes consistent with medical complexity.

Exclusion Criteria

We used the APR‐DRG system, which leverages ICD‐9‐CM codes to identify the health problem most responsible for the hospitalization, to refine the study cohort. We excluded hospitalizations that were classified by the APR‐DRG system as neonatal, as we did not wish to focus on LOS in the neonatal intensive care unit (ICU) or for birth admissions. Similarly, hospitalizations for chemotherapy (APR‐DRG 693) or malignancy (identified with previously used ICD‐9‐CM codes)[20] were also excluded because long LOS is anticipated. We also excluded hospitalizations for medical rehabilitation (APR‐DRG 860).

Outcome Measures

The primary outcome measure was long LOS, defined as LOS 10 days. The cut point of LOS 10 days represents the 90th percentile of LOS for all children, with and without medical complexity, hospitalized during 2013 to 2014. LOS 10 days has previously been used as a threshold of long LOS.[21] For hospitalizations involving transfer at admission from another acute care facility, LOS was measured from the date of transfer. We also assessed hospitals' cost attributable to long LOS admissions.

Patient Demographics and Clinical Characteristics

We measured demographic characteristics including age, gender, race/ethnicity, insurance type, and distance traveled (the linear distance between the centroid of the patient's home ZIP code and the centroid of the hospital's ZIP code). Clinical characteristics included CRG classification, complex chronic condition (CCC), and dependence on medical technology. CCCs are defined as any medical condition that can be reasonably expected to last at least 12 months (unless death intervenes) and to involve either several different organ systems or 1 system severely enough to require specialty pediatric care and probably some period of hospitalization in a tertiary care center.[20] Medical technology included devices used to optimize the health and functioning of the child (eg, gastrostomy, tracheostomy, cerebrospinal fluid shunt).[22]

Hospitalization Characteristics

Characteristics of the hospitalization included transfer from an outside facility, ICU admission, surgical procedure (using surgical APR‐DRGs), and discharge disposition (home, skilled nursing facility, home health services, death, other). Cost of the hospitalization was estimated in the PHIS from charges using hospital and year‐specific ratios of cost to charge.

Statistical Analysis

Continuous data (eg, distance from hospital to home residence) were described with median and interquartile ranges (IQR) because they were not normally distributed. Categorical data (eg, type of chronic condition) were described with counts and frequencies. In bivariate analyses, demographic, clinical, and hospitalization characteristics were stratified by LOS (long LOS vs LOS <10 days), and compared using 2 statistics or Wilcoxon rank sum tests as appropriate.

We modeled the likelihood of experiencing a long LOS using generalized linear mixed effects models with a random hospital intercept and discharge‐level fixed effects for age, gender, payor, CCC type, ICU utilization, transfer status, a medical/surgical admission indicator derived from the APR‐DRG, and CRG assigned to each hospitalization. To examine hospital‐to‐hospital variability, we generated hospital risk‐adjusted rates of long LOS from these models. Similar models and hospital risk‐adjusted rates were built for a post hoc correlational analysis of 30‐day all cause readmission, where hospitals' rates and percent of long LOS were compared with a Pearson correlation coefficient. Also, for our multivariable models, we performed a sensitivity analysis using an alternative definition of long LOS as 4 days (the 75th percentile of LOS for all children, with and without medical complexity, hospitalized during 20132014). All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC), and P values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Study Population

There were 954,018 hospitalizations of 217,163 CMC at 44 children's hospitals included for analysis. Forty‐seven percent of hospitalizations were for females, 49.4% for non‐Hispanic whites, and 61.1% for children with government insurance. Fifteen percent (n = 142,082) had a long LOS of 10 days. The median (IQR) LOS of hospitalizations <10 days versus 10 days were 2 (IQR, 14) and 16 days (IQR, 1226), respectively. Long LOS hospitalizations accounted for 61.1% (3.7 million) hospital days and 61.8% ($13.7 billion) of total hospitalization costs for all CMC in the cohort (Table 1).

| Characteristic | Overall (n = 954,018) | Length of Stay | |

|---|---|---|---|

| <10 Days (n = 811,936) | 10 Days (n = 142,082) | ||

| |||

| Age at admission, y, % | |||

| <1 | 14.6 | 12.7 | 25.7 |

| 14 | 27.1 | 27.9 | 22.4 |

| 59 | 20.1 | 21.0 | 14.9 |

| 1018 | 33.6 | 34.0 | 31.7 |

| 18+ | 4.6 | 4.4 | 5.4 |

| Gender, % | |||

| Female | 47.0 | 46.9 | 47.5 |

| Race/ethnicity, % | |||

| Non‐Hispanic white | 49.4 | 49.4 | 49.4 |

| Non‐Hispanic black | 23.1 | 23.8 | 19.3 |

| Hispanic | 18.2 | 17.8 | 20.4 |

| Asian | 2.0 | 1.9 | 2.3 |

| Other | 7.4 | 7.1 | 8.6 |

| Complex chronic condition, % | |||

| Any | 79.5 | 77.3 | 91.8 |

| Technology assistance | 37.1 | 34.1 | 54.2 |

| Gastrointestinal | 30.0 | 27.2 | 45.9 |

| Neuromuscular | 28.2 | 27.7 | 30.9 |

| Cardiovascular | 16.8 | 14.5 | 29.9 |

| Respiratory | 14.1 | 11.5 | 29.4 |

| Congenital/genetic defect | 17.2 | 16.7 | 20.2 |

| Metabolic | 9.9 | 8.9 | 15.4 |

| Renal | 10.1 | 9.5 | 13.8 |

| Hematology/emmmunodeficiency | 11.7 | 12.0 | 10.0 |

| Neonatal | 3.8 | 3.1 | 7.7 |

| Transplantation | 4.5 | 4.2 | 6.7 |

| Clinical risk group, % | |||

| Chronic condition in 2 systems | 68.4 | 71.2 | 53.9 |

| Catastrophic chronic condition | 31.4 | 28.8 | 46.1 |

| Distance from hospital to home residence in miles, median [IQR] | 16.2 [7.440.4] | 15.8 [7.338.7] | 19.1 [8.552.6] |

| Transferred from outside hospital (%) | 6.5 | 5.3 | 13.6 |

| Admitted for surgery, % | 23.4 | 20.7 | 38.7 |

| Use of intensive care, % | 19.6 | 14.9 | 46.5 |

| Discharge disposition, % | |||

| Home | 91.2 | 92.9 | 81.4 |

| Home healthcare | 4.5 | 3.5 | 9.9 |

| Other | 2.9 | 2.6 | 4.5 |

| Postacute care facility | 1.1 | 0.8 | 3.1 |

| Died | 0.4 | 0.3 | 1.1 |

| Payor, % | |||

| Government | 61.1 | 60.6 | 63.5 |

| Private | 33.2 | 33.6 | 30.9 |

| Other | 5.7 | 5.7 | 5.7 |

| Hospital resource use | |||

| Median length of stay [IQR] | 3 [16] | 2 [14] | 16 [1226] |

| Median hospital cost [IQR] | $8,144 [$4,122$18,447] | $6,689 [$3,685$12,395] | $49,207 [$29,444$95,738] |

| Total hospital cost, $, billions | $22.2 | $8.5 | $13.7 |

Demographics and Clinical Characteristics of Children With and Without Long LOS

Compared with hospitalized CMC with LOS <10 days, a higher percentage of hospitalizations with LOS 10 days were CMC age <1 year (25.7% vs 12.7%, P < 0.001) and Hispanic (20.4% vs 17.8%, P < 0.001). CMC hospitalizations with a long LOS had a higher percentage of any CCC (91.8% vs 77.3%, P < 0.001); the most common CCCs were gastrointestinal (45.9%), neuromuscular (30.9%), and cardiovascular (29.9%). Hospitalizations of CMC with a long LOS had a higher percentage of a catastrophic chronic condition (46.1% vs 28.8%, P < 0.001) and technology dependence (46.1% vs 28.8%, P < 0.001) (Table 1).

Hospitalization Characteristics of Children With and Without Long LOS

Compared with hospitalizations of CMC with LOS <10 days, hospitalizations of CMC with a long LOS more often involved transfer in from another hospital at admission (13.6% vs 5.3%, P < 0.001). CMC hospital stays with a long LOS more often involved surgery (38.7% vs 20.7%, P < 0.001) and use of intensive care (46.5% vs 14.9%; P < 0.001). A higher percentage of CMC with long LOS were discharged with home health services (9.9% vs 3.5%; P < 0.001) (Table 1).

The most common admitting diagnoses and CCCs for hospitalizations of CMC with long LOS are presented in Table 2. The two most prevalent APR‐DRGs in CMC hospitalizations lasting 10 days or longer were cystic fibrosis (10.7%) and respiratory system disease with ventilator support (5.5%). The two most common chronic condition characteristics represented among long CMC hospitalizations were gastrointestinal devices (eg, gastrostomy tube) (39.7%) and heart and great vessel malformations (eg, tetralogy of Fallot) (12.8%). The 5 most common CCC subcategories, as listed in Table 2, account for nearly 100% of the patients with long LOS hospitalizations.

| |

| Most common reason for admission* | |

| Cystic fibrosis | 10.7% |

| Respiratory system diagnosis with ventilator support 96+ hours | 5.5% |

| Malfunction, reaction, and complication of cardiac or vascular device or procedure | 2.8% |

| Craniotomy except for trauma | 2.6% |

| Major small and large bowel procedures | 2.3% |

| Most common complex chronic condition | |

| Gastrointestinal devices | 39.7% |

| Heart and great vessel malformations | 12.8% |

| Cystic fibrosis | 12.5% |

| Dysrhythmias | 11.0% |

| Respiratory devices | 10.7% |

Multivariable Analysis of Characteristics Associated With Long LOS

In multivariable analysis, the highest likelihood of long LOS was experienced by children who received care in the ICU (odds ratio [OR]: 3.5, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 3.43.5), who had a respiratory CCC (OR: 2.7, 95% CI: 2.62.7), and who were transferred from another acute care hospital at admission (OR: 2.1, 95% CI: 2.0, 2.1). The likelihood of long LOS was also higher in children <1 year of age (OR: 1.2, 95% CI: 1.21.3), and Hispanic children (OR: 1.1, 95% CI 1.0‐1.10) (Table 3). Similar multivariable findings were observed in sensitivity analysis using the 75th percentile of LOS (4 days) as the model outcome.

| Characteristic | Odds Ratio (95% CI) of LOS 10 Days | P Value |

|---|---|---|

| ||

| Use of intensive care | 3.5 (3.4‐3.5) | <0.001 |

| Transfer from another acute‐care hospital | 2.1 (2.0‐2.1) | <0.001 |

| Procedure/surgery | 1.8 (1.8‐1.9) | <0.001 |

| Complex chronic condition | ||

| Respiratory | 2.7 (2.6‐2.7) | <0.001 |

| Gastrointestinal | 1.8 (1.8‐1.8) | <0.001 |

| Metabolic | 1.7 (1.7‐1.7) | <0.001 |

| Cardiovascular | 1.6 (1.5‐1.6) | <0.001 |

| Neonatal | 1.5 (1.5‐1.5) | <0.001 |

| Renal | 1.4 (1.4‐1.4) | <0.001 |

| Transplant | 1.4 (1.4‐1.4) | <0.001 |

| Hematology and immunodeficiency | 1.3 (1.3‐1.3) | <0.001 |

| Technology assistance | 1.1 (1.1, 1.1) | <0.001 |

| Neuromuscular | 0.9 (0.9‐0.9) | <0.001 |

| Congenital or genetic defect | 0.8 (0.8‐0.8) | <0.001 |

| Age at admission, y | ||

| <1 | 1.2 (1.2‐1.3) | <0.001 |

| 14 | 0.5 (0.5‐0.5) | <0.001 |

| 59 | 0.6 (0.6‐0.6) | <0.001 |

| 1018 | 0.9 (0.9‐0.9) | <0.001 |

| 18+ | Reference | |

| Male | 0.9 (0.9‐0.9) | <0.001 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| Non‐Hispanic black | 0.9 (0.9‐0.9) | <0.001 |

| Hispanic | 1.1 (1.0‐1.1) | <0.001 |

| Asian | 1.0 (1.0‐1.1) | 0.3 |

| Other | 1.1 (1.1‐1.1) | <0.001 |

| Non‐Hispanic white | Reference | |

| Payor | ||

| Private | 0.9 (0.8 0.9) | <0.001 |

| Other | 1.0 (1.0‐1.0) | 0.4 |

| Government | Reference | |

| Season | ||

| Spring | 1.0 (1.0 1.0) | <0.001 |

| Summer | 0.9 (0.9‐0.9) | <0.001 |

| Fall | 1.0 (0.9‐1.0) | <0.001 |

| Winter | Reference | |

Variation in the Prevalence of Long LOS Across Children's Hospitals

After controlling for demographic, clinical, and hospital characteristics associated with long LOS, there was significant (P < 0.001) variation in the prevalence of long LOS for CMC across children's hospitals in the cohort (range, 10.3%21.8%) (Figure 1). Twelve (27%) hospitals had a significantly (P < 0.001) higher prevalence of long LOS for their hospitalized CMC, compared to the mean. Eighteen (41%) had a significantly (P < 0.001) lower prevalence of long LOS for their hospitalized CMC. There was also significant variation across hospitals with respect to cost, with 49.7% to 73.7% of all hospital costs of CMC attributed to long LOS hospitalizations. Finally, there was indirect correlation with the prevalence of LOS across hospitals and the hospitals' 30‐day readmission rate ( = 0.3; P = 0.04). As the prevalence of long LOS increased, the readmission rate decreased.

DISCUSSION

The main findings from this study suggest that a small percentage of CMC experiencing long LOS account for the majority of hospital bed days and cost of all hospitalized CMC in children's hospitals. The likelihood of long LOS varies significantly by CMC's age, race/ethnicity, and payor as well as by type and number of chronic conditions. Among CMC with long LOS, the use of gastrointestinal devices such as gastrostomy tubes, as well as congenital heart disease, were highly prevalent. In multivariable analysis, the characteristics most strongly associated with LOS 10 days were use of the ICU, respiratory complex chronic condition, and transfer from another medical facility at admission. After adjusting for these factors, there was significant variation in the prevalence of LOS 10 days for CMC across children's hospitals.

Although it is well known that CMC as a whole have a major impact on resource use in children's hospitals, this study reveals that 15% of hospitalizations of CMC account for 62% of all hospital costs of CMC. That is, a small fraction of hospitalizations of CMC is largely responsible for the significant financial impact of hospital resource use. To date, most clinical efforts and policies striving to reduce hospital use in CMC have focused on avoiding readmissions or index hospital admissions entirely, rather than improving the efficiency of hospital care after admission occurs.[23, 24, 25, 26] In the adult population, the impact of long LOS on hospital costs has been recognized, and several Medicare incentive programs have focused on in‐hospital timeliness and efficiency. As a result, LOS in Medicare beneficiaries has decreased dramatically over the past 2 decades.[27, 28, 29, 30] Optimizing the efficiency of hospital care for CMC may be an important goal to pursue, especially with precedent set in the adult literature.

Perhaps the substantial variation across hospitals in the prevalence of long LOS in CMC indicates opportunity to improve the efficiency of their inpatient care. This variation was not due to differences across hospitals' case mix of CMC. Further investigation is needed to determine how much of it is due to differences in quality of care. Clinical practice guidelines for hospital treatment of common illnesses usually exclude CMC. In our clinical experience across 9 children's hospitals, we have experienced varying approaches to setting discharge goals (ie, parameters on how healthy the child needs to be to ensure a successful hospital discharge) for CMC.[31] When the goals are absent or not clearly articulated, they can contribute to a prolonged hospitalization. Some families of CMC report significant issues when working with pediatric hospital staff to assess their child's discharge readiness.[7, 32, 33] In addition, there is significant variation across states and regions in access to and quality of post‐discharge health services (eg, home nursing, postacute care, durable medical equipment).[34, 35] In some areas, many CMC are not actively involved with their primary care physician.[5] These issues might also influence the ability of some children's hospitals to efficiently discharge CMC to a safe and supportive post‐discharge environment. Further examination of hospital outliersthose with the lowest and highest percentage of CMC hospitalizations with long LOSmay reveal opportunities to identify and spread best practices.

The demographic and clinical factors associated with long LOS in the present study, including age, ICU use, and transfer from another hospital, might help hospitals target which CMC have the greatest risk for experiencing long LOS. We found that infants age <1 year had longer LOS when compared with older children. Similar to our findings, younger‐aged children hospitalized with bronchiolitis have longer LOS.[36] Certainly, infants with medical complexity, in general, are a high‐acuity population with the potential for rapid clinical deterioration during an acute illness. Prolonged hospitalization for treatment and stabilization may be expected for many of them. Additional investigation is warranted to examine ICU use in CMC, and whether ICU admission or duration can be safely prevented or abbreviated. Opportunities to assess the quality of transfers into children's hospitals of CMC admitted to outside hospitals may be necessary. A study of pediatric burn patients reported that patients initially stabilized at a facility that was not a burn center and subsequently transferred to a burn center had a longer LOS than patients solely treated at a designated burn center.[37] Furthermore, events during transport itself may adversely impact the stability of an already fragile patient. Interventions to optimize the quality of care provided by transport teams have resulted in decreased LOS at the receiving hospital.[38]

This study's findings should be considered in the context of several limitations. Absent a gold‐standard definition of long LOS, we used the distribution of LOS across patients to inform our methods; LOS at the 90th percentile was selected as long. Although our sensitivity analysis using LOS at the 75th percentile produced similar findings, other cut points in LOS might be associated with different results. The study is not positioned to determine how much of the reported LOS was excessive, unnecessary, or preventable. The study findings may not generalize to types of hospitals not contained in PHIS (eg, nonchildren's hospitals and community hospitals). We did not focus on the impact of a new diagnosis (eg, new chronic illness) or acute in‐hospital event (eg, nosocomial infection) on prolonged LOS; future studies should investigate these clinical events with LOS.

PHIS does not contain information regarding characteristics that could influence LOS, including the children's social and familial attributes, transportation availability, home equipment needs, and local availability of postacute care facilities. Moreover, PHIS does not contain information about the hospital discharge procedures, process, or personnel across hospitals, which could influence LOS. Future studies on prolonged LOS should consider assessing this information. Because of the large sample size of hospitalizations included, the statistical power for the analyses was strong, rendering it possible that some findings that were statistically significant might have modest clinical significance (eg, relationship of Hispanic ethnicity with prolonged LOS). We could not determine why a positive correlation was not observed between hospitals' long LOS prevalence and their percentage of cost associated with long LOS; future studies should investigate the reasons for this finding.

Despite these limitations, the findings of the present study highlight the significance of long LOS in hospitalized CMC. These long hospitalizations account for a significant proportion of all hospital costs for this important population of children. The prevalence of long LOS for CMC varies considerably across children's hospitals, even after accounting for the case mix. Efforts to curtail hospital resource use and costs for CMC may benefit from focus on long LOS.

Children with medical complexity (CMC) have complex and chronic health conditions that often involve multiple organ systems and severely affect cognitive and physical functioning. Although the prevalence of CMC is low (1% of all children), they account for nearly one‐fifth of all pediatric admissions and one‐half of all hospital days and charges in the United States.[1] Over the last decade, CMC have had a particularly large and increasing impact in tertiary‐care children's hospitals.[1, 2] The Institute of Medicine has identified CMC as a priority population for a revised healthcare system.[3]

Medical homes, hospitals, health plans, states, federal agencies, and others are striving to reduce excessive hospital use in CMC because of its high cost.[4, 5, 6] Containing length of stay (LOS)an increasingly used indicator of the time sensitiveness and efficiency of hospital careis a common aim across these initiatives. CMC have longer hospitalizations than children without medical complexity. Speculated reasons for this are that CMC tend to have (1) higher severity of acute illnesses (eg, pneumonia, cellulitis), (2) prolonged recovery time in the hospital, and (3) higher risk of adverse events in the hospital. Moreover, hospital clinicians caring for CMC often find it difficult to determine discharge readiness, given that many CMC do not return to a completely healthy baseline.[7]

Little is known about long LOS in CMC, including which CMC have the highest risk of experiencing such stays and which stays might have the greatest opportunity to be shortened. Patient characteristics associated with prolonged length of stay have been studied extensively for many pediatric conditions (eg, asthma).[8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14] However, most of these studies excluded CMC. Therefore, the objectives of this study were to examine (1) the prevalence of long LOS in CMC, (2) patient characteristics associated with long LOS, and (3) hospital‐to‐hospital variation in prevalence of long LOS hospitalizations.

METHODS

Study Design and Data Source

This study is a multicenter, retrospective cohort analysis of the Pediatric Health Information System (PHIS). PHIS is an administrative database of 44 not for profit, tertiary care pediatric hospitals affiliated with the Children's Hospital Association (CHA) (Overland Park, KS). PHIS contains data regarding patient demographics, diagnoses, and procedures (with International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification [ICD‐9‐CM] codes), All‐Patient Refined Diagnostic Related Groups version 30 (APR‐DRGs) (3M Health Information Systems, Salt Lake City, UT), and service lines that aggregate the APR‐DRGs into 38 distinct groups. Data quality and reliability are assured through CHA and participating hospitals. In accordance with the policies of the Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center Institutional Review Board, this study of deidentified data was not considered human subjects research.

Study Population

Inclusion Criteria

Children discharged following an observation or inpatient admission from a hospital participating in the PHIS database between January 1, 2013 and December 31, 2014 were eligible for inclusion if they were considered medically complex. Medical complexity was defined using Clinical Risk Groups (CRGs) version 1.8, developed by 3M Health Information Systems and the National Association of Children's Hospitals and Related Institutions. CRGs were used to assign each hospitalized patient to 1 of 9 mutually exclusive chronicity groups according to the presence, type, and severity of chronic conditions.[15, 16, 17, 18] Each patient's CRG designation was based on 2 years of previous hospital encounters.

As defined in prior studies and definitional frameworks of CMC,[1] patients belonging to CRG group 6 (significant chronic disease in 2 organ systems), CRG group 7 (dominant chronic disease in 3 organ systems), and CRG group 9 (catastrophic condition) were considered medically complex.[17, 19] Patients with malignancies (CRG group 8) were not included for analysis because they are a unique population with anticipated, long hospital stays. Patients with CRG group 5, representing those with chronic conditions affecting a single body system, were also not included because most do not have attributes consistent with medical complexity.

Exclusion Criteria

We used the APR‐DRG system, which leverages ICD‐9‐CM codes to identify the health problem most responsible for the hospitalization, to refine the study cohort. We excluded hospitalizations that were classified by the APR‐DRG system as neonatal, as we did not wish to focus on LOS in the neonatal intensive care unit (ICU) or for birth admissions. Similarly, hospitalizations for chemotherapy (APR‐DRG 693) or malignancy (identified with previously used ICD‐9‐CM codes)[20] were also excluded because long LOS is anticipated. We also excluded hospitalizations for medical rehabilitation (APR‐DRG 860).

Outcome Measures

The primary outcome measure was long LOS, defined as LOS 10 days. The cut point of LOS 10 days represents the 90th percentile of LOS for all children, with and without medical complexity, hospitalized during 2013 to 2014. LOS 10 days has previously been used as a threshold of long LOS.[21] For hospitalizations involving transfer at admission from another acute care facility, LOS was measured from the date of transfer. We also assessed hospitals' cost attributable to long LOS admissions.

Patient Demographics and Clinical Characteristics

We measured demographic characteristics including age, gender, race/ethnicity, insurance type, and distance traveled (the linear distance between the centroid of the patient's home ZIP code and the centroid of the hospital's ZIP code). Clinical characteristics included CRG classification, complex chronic condition (CCC), and dependence on medical technology. CCCs are defined as any medical condition that can be reasonably expected to last at least 12 months (unless death intervenes) and to involve either several different organ systems or 1 system severely enough to require specialty pediatric care and probably some period of hospitalization in a tertiary care center.[20] Medical technology included devices used to optimize the health and functioning of the child (eg, gastrostomy, tracheostomy, cerebrospinal fluid shunt).[22]

Hospitalization Characteristics

Characteristics of the hospitalization included transfer from an outside facility, ICU admission, surgical procedure (using surgical APR‐DRGs), and discharge disposition (home, skilled nursing facility, home health services, death, other). Cost of the hospitalization was estimated in the PHIS from charges using hospital and year‐specific ratios of cost to charge.

Statistical Analysis

Continuous data (eg, distance from hospital to home residence) were described with median and interquartile ranges (IQR) because they were not normally distributed. Categorical data (eg, type of chronic condition) were described with counts and frequencies. In bivariate analyses, demographic, clinical, and hospitalization characteristics were stratified by LOS (long LOS vs LOS <10 days), and compared using 2 statistics or Wilcoxon rank sum tests as appropriate.

We modeled the likelihood of experiencing a long LOS using generalized linear mixed effects models with a random hospital intercept and discharge‐level fixed effects for age, gender, payor, CCC type, ICU utilization, transfer status, a medical/surgical admission indicator derived from the APR‐DRG, and CRG assigned to each hospitalization. To examine hospital‐to‐hospital variability, we generated hospital risk‐adjusted rates of long LOS from these models. Similar models and hospital risk‐adjusted rates were built for a post hoc correlational analysis of 30‐day all cause readmission, where hospitals' rates and percent of long LOS were compared with a Pearson correlation coefficient. Also, for our multivariable models, we performed a sensitivity analysis using an alternative definition of long LOS as 4 days (the 75th percentile of LOS for all children, with and without medical complexity, hospitalized during 20132014). All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC), and P values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Study Population

There were 954,018 hospitalizations of 217,163 CMC at 44 children's hospitals included for analysis. Forty‐seven percent of hospitalizations were for females, 49.4% for non‐Hispanic whites, and 61.1% for children with government insurance. Fifteen percent (n = 142,082) had a long LOS of 10 days. The median (IQR) LOS of hospitalizations <10 days versus 10 days were 2 (IQR, 14) and 16 days (IQR, 1226), respectively. Long LOS hospitalizations accounted for 61.1% (3.7 million) hospital days and 61.8% ($13.7 billion) of total hospitalization costs for all CMC in the cohort (Table 1).

| Characteristic | Overall (n = 954,018) | Length of Stay | |

|---|---|---|---|

| <10 Days (n = 811,936) | 10 Days (n = 142,082) | ||

| |||

| Age at admission, y, % | |||

| <1 | 14.6 | 12.7 | 25.7 |

| 14 | 27.1 | 27.9 | 22.4 |

| 59 | 20.1 | 21.0 | 14.9 |

| 1018 | 33.6 | 34.0 | 31.7 |

| 18+ | 4.6 | 4.4 | 5.4 |

| Gender, % | |||

| Female | 47.0 | 46.9 | 47.5 |

| Race/ethnicity, % | |||

| Non‐Hispanic white | 49.4 | 49.4 | 49.4 |

| Non‐Hispanic black | 23.1 | 23.8 | 19.3 |

| Hispanic | 18.2 | 17.8 | 20.4 |

| Asian | 2.0 | 1.9 | 2.3 |

| Other | 7.4 | 7.1 | 8.6 |

| Complex chronic condition, % | |||

| Any | 79.5 | 77.3 | 91.8 |

| Technology assistance | 37.1 | 34.1 | 54.2 |

| Gastrointestinal | 30.0 | 27.2 | 45.9 |

| Neuromuscular | 28.2 | 27.7 | 30.9 |

| Cardiovascular | 16.8 | 14.5 | 29.9 |

| Respiratory | 14.1 | 11.5 | 29.4 |

| Congenital/genetic defect | 17.2 | 16.7 | 20.2 |

| Metabolic | 9.9 | 8.9 | 15.4 |

| Renal | 10.1 | 9.5 | 13.8 |

| Hematology/emmmunodeficiency | 11.7 | 12.0 | 10.0 |

| Neonatal | 3.8 | 3.1 | 7.7 |

| Transplantation | 4.5 | 4.2 | 6.7 |

| Clinical risk group, % | |||

| Chronic condition in 2 systems | 68.4 | 71.2 | 53.9 |

| Catastrophic chronic condition | 31.4 | 28.8 | 46.1 |

| Distance from hospital to home residence in miles, median [IQR] | 16.2 [7.440.4] | 15.8 [7.338.7] | 19.1 [8.552.6] |

| Transferred from outside hospital (%) | 6.5 | 5.3 | 13.6 |

| Admitted for surgery, % | 23.4 | 20.7 | 38.7 |

| Use of intensive care, % | 19.6 | 14.9 | 46.5 |

| Discharge disposition, % | |||

| Home | 91.2 | 92.9 | 81.4 |

| Home healthcare | 4.5 | 3.5 | 9.9 |

| Other | 2.9 | 2.6 | 4.5 |

| Postacute care facility | 1.1 | 0.8 | 3.1 |

| Died | 0.4 | 0.3 | 1.1 |

| Payor, % | |||

| Government | 61.1 | 60.6 | 63.5 |

| Private | 33.2 | 33.6 | 30.9 |

| Other | 5.7 | 5.7 | 5.7 |

| Hospital resource use | |||

| Median length of stay [IQR] | 3 [16] | 2 [14] | 16 [1226] |

| Median hospital cost [IQR] | $8,144 [$4,122$18,447] | $6,689 [$3,685$12,395] | $49,207 [$29,444$95,738] |

| Total hospital cost, $, billions | $22.2 | $8.5 | $13.7 |

Demographics and Clinical Characteristics of Children With and Without Long LOS

Compared with hospitalized CMC with LOS <10 days, a higher percentage of hospitalizations with LOS 10 days were CMC age <1 year (25.7% vs 12.7%, P < 0.001) and Hispanic (20.4% vs 17.8%, P < 0.001). CMC hospitalizations with a long LOS had a higher percentage of any CCC (91.8% vs 77.3%, P < 0.001); the most common CCCs were gastrointestinal (45.9%), neuromuscular (30.9%), and cardiovascular (29.9%). Hospitalizations of CMC with a long LOS had a higher percentage of a catastrophic chronic condition (46.1% vs 28.8%, P < 0.001) and technology dependence (46.1% vs 28.8%, P < 0.001) (Table 1).

Hospitalization Characteristics of Children With and Without Long LOS

Compared with hospitalizations of CMC with LOS <10 days, hospitalizations of CMC with a long LOS more often involved transfer in from another hospital at admission (13.6% vs 5.3%, P < 0.001). CMC hospital stays with a long LOS more often involved surgery (38.7% vs 20.7%, P < 0.001) and use of intensive care (46.5% vs 14.9%; P < 0.001). A higher percentage of CMC with long LOS were discharged with home health services (9.9% vs 3.5%; P < 0.001) (Table 1).

The most common admitting diagnoses and CCCs for hospitalizations of CMC with long LOS are presented in Table 2. The two most prevalent APR‐DRGs in CMC hospitalizations lasting 10 days or longer were cystic fibrosis (10.7%) and respiratory system disease with ventilator support (5.5%). The two most common chronic condition characteristics represented among long CMC hospitalizations were gastrointestinal devices (eg, gastrostomy tube) (39.7%) and heart and great vessel malformations (eg, tetralogy of Fallot) (12.8%). The 5 most common CCC subcategories, as listed in Table 2, account for nearly 100% of the patients with long LOS hospitalizations.

| |

| Most common reason for admission* | |

| Cystic fibrosis | 10.7% |

| Respiratory system diagnosis with ventilator support 96+ hours | 5.5% |

| Malfunction, reaction, and complication of cardiac or vascular device or procedure | 2.8% |

| Craniotomy except for trauma | 2.6% |

| Major small and large bowel procedures | 2.3% |

| Most common complex chronic condition | |

| Gastrointestinal devices | 39.7% |

| Heart and great vessel malformations | 12.8% |

| Cystic fibrosis | 12.5% |

| Dysrhythmias | 11.0% |

| Respiratory devices | 10.7% |

Multivariable Analysis of Characteristics Associated With Long LOS

In multivariable analysis, the highest likelihood of long LOS was experienced by children who received care in the ICU (odds ratio [OR]: 3.5, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 3.43.5), who had a respiratory CCC (OR: 2.7, 95% CI: 2.62.7), and who were transferred from another acute care hospital at admission (OR: 2.1, 95% CI: 2.0, 2.1). The likelihood of long LOS was also higher in children <1 year of age (OR: 1.2, 95% CI: 1.21.3), and Hispanic children (OR: 1.1, 95% CI 1.0‐1.10) (Table 3). Similar multivariable findings were observed in sensitivity analysis using the 75th percentile of LOS (4 days) as the model outcome.

| Characteristic | Odds Ratio (95% CI) of LOS 10 Days | P Value |

|---|---|---|

| ||

| Use of intensive care | 3.5 (3.4‐3.5) | <0.001 |

| Transfer from another acute‐care hospital | 2.1 (2.0‐2.1) | <0.001 |

| Procedure/surgery | 1.8 (1.8‐1.9) | <0.001 |

| Complex chronic condition | ||

| Respiratory | 2.7 (2.6‐2.7) | <0.001 |

| Gastrointestinal | 1.8 (1.8‐1.8) | <0.001 |

| Metabolic | 1.7 (1.7‐1.7) | <0.001 |

| Cardiovascular | 1.6 (1.5‐1.6) | <0.001 |

| Neonatal | 1.5 (1.5‐1.5) | <0.001 |

| Renal | 1.4 (1.4‐1.4) | <0.001 |

| Transplant | 1.4 (1.4‐1.4) | <0.001 |

| Hematology and immunodeficiency | 1.3 (1.3‐1.3) | <0.001 |

| Technology assistance | 1.1 (1.1, 1.1) | <0.001 |

| Neuromuscular | 0.9 (0.9‐0.9) | <0.001 |

| Congenital or genetic defect | 0.8 (0.8‐0.8) | <0.001 |

| Age at admission, y | ||

| <1 | 1.2 (1.2‐1.3) | <0.001 |

| 14 | 0.5 (0.5‐0.5) | <0.001 |

| 59 | 0.6 (0.6‐0.6) | <0.001 |

| 1018 | 0.9 (0.9‐0.9) | <0.001 |

| 18+ | Reference | |

| Male | 0.9 (0.9‐0.9) | <0.001 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| Non‐Hispanic black | 0.9 (0.9‐0.9) | <0.001 |

| Hispanic | 1.1 (1.0‐1.1) | <0.001 |

| Asian | 1.0 (1.0‐1.1) | 0.3 |

| Other | 1.1 (1.1‐1.1) | <0.001 |

| Non‐Hispanic white | Reference | |

| Payor | ||

| Private | 0.9 (0.8 0.9) | <0.001 |

| Other | 1.0 (1.0‐1.0) | 0.4 |

| Government | Reference | |

| Season | ||

| Spring | 1.0 (1.0 1.0) | <0.001 |

| Summer | 0.9 (0.9‐0.9) | <0.001 |

| Fall | 1.0 (0.9‐1.0) | <0.001 |

| Winter | Reference | |

Variation in the Prevalence of Long LOS Across Children's Hospitals

After controlling for demographic, clinical, and hospital characteristics associated with long LOS, there was significant (P < 0.001) variation in the prevalence of long LOS for CMC across children's hospitals in the cohort (range, 10.3%21.8%) (Figure 1). Twelve (27%) hospitals had a significantly (P < 0.001) higher prevalence of long LOS for their hospitalized CMC, compared to the mean. Eighteen (41%) had a significantly (P < 0.001) lower prevalence of long LOS for their hospitalized CMC. There was also significant variation across hospitals with respect to cost, with 49.7% to 73.7% of all hospital costs of CMC attributed to long LOS hospitalizations. Finally, there was indirect correlation with the prevalence of LOS across hospitals and the hospitals' 30‐day readmission rate ( = 0.3; P = 0.04). As the prevalence of long LOS increased, the readmission rate decreased.

DISCUSSION

The main findings from this study suggest that a small percentage of CMC experiencing long LOS account for the majority of hospital bed days and cost of all hospitalized CMC in children's hospitals. The likelihood of long LOS varies significantly by CMC's age, race/ethnicity, and payor as well as by type and number of chronic conditions. Among CMC with long LOS, the use of gastrointestinal devices such as gastrostomy tubes, as well as congenital heart disease, were highly prevalent. In multivariable analysis, the characteristics most strongly associated with LOS 10 days were use of the ICU, respiratory complex chronic condition, and transfer from another medical facility at admission. After adjusting for these factors, there was significant variation in the prevalence of LOS 10 days for CMC across children's hospitals.

Although it is well known that CMC as a whole have a major impact on resource use in children's hospitals, this study reveals that 15% of hospitalizations of CMC account for 62% of all hospital costs of CMC. That is, a small fraction of hospitalizations of CMC is largely responsible for the significant financial impact of hospital resource use. To date, most clinical efforts and policies striving to reduce hospital use in CMC have focused on avoiding readmissions or index hospital admissions entirely, rather than improving the efficiency of hospital care after admission occurs.[23, 24, 25, 26] In the adult population, the impact of long LOS on hospital costs has been recognized, and several Medicare incentive programs have focused on in‐hospital timeliness and efficiency. As a result, LOS in Medicare beneficiaries has decreased dramatically over the past 2 decades.[27, 28, 29, 30] Optimizing the efficiency of hospital care for CMC may be an important goal to pursue, especially with precedent set in the adult literature.

Perhaps the substantial variation across hospitals in the prevalence of long LOS in CMC indicates opportunity to improve the efficiency of their inpatient care. This variation was not due to differences across hospitals' case mix of CMC. Further investigation is needed to determine how much of it is due to differences in quality of care. Clinical practice guidelines for hospital treatment of common illnesses usually exclude CMC. In our clinical experience across 9 children's hospitals, we have experienced varying approaches to setting discharge goals (ie, parameters on how healthy the child needs to be to ensure a successful hospital discharge) for CMC.[31] When the goals are absent or not clearly articulated, they can contribute to a prolonged hospitalization. Some families of CMC report significant issues when working with pediatric hospital staff to assess their child's discharge readiness.[7, 32, 33] In addition, there is significant variation across states and regions in access to and quality of post‐discharge health services (eg, home nursing, postacute care, durable medical equipment).[34, 35] In some areas, many CMC are not actively involved with their primary care physician.[5] These issues might also influence the ability of some children's hospitals to efficiently discharge CMC to a safe and supportive post‐discharge environment. Further examination of hospital outliersthose with the lowest and highest percentage of CMC hospitalizations with long LOSmay reveal opportunities to identify and spread best practices.

The demographic and clinical factors associated with long LOS in the present study, including age, ICU use, and transfer from another hospital, might help hospitals target which CMC have the greatest risk for experiencing long LOS. We found that infants age <1 year had longer LOS when compared with older children. Similar to our findings, younger‐aged children hospitalized with bronchiolitis have longer LOS.[36] Certainly, infants with medical complexity, in general, are a high‐acuity population with the potential for rapid clinical deterioration during an acute illness. Prolonged hospitalization for treatment and stabilization may be expected for many of them. Additional investigation is warranted to examine ICU use in CMC, and whether ICU admission or duration can be safely prevented or abbreviated. Opportunities to assess the quality of transfers into children's hospitals of CMC admitted to outside hospitals may be necessary. A study of pediatric burn patients reported that patients initially stabilized at a facility that was not a burn center and subsequently transferred to a burn center had a longer LOS than patients solely treated at a designated burn center.[37] Furthermore, events during transport itself may adversely impact the stability of an already fragile patient. Interventions to optimize the quality of care provided by transport teams have resulted in decreased LOS at the receiving hospital.[38]

This study's findings should be considered in the context of several limitations. Absent a gold‐standard definition of long LOS, we used the distribution of LOS across patients to inform our methods; LOS at the 90th percentile was selected as long. Although our sensitivity analysis using LOS at the 75th percentile produced similar findings, other cut points in LOS might be associated with different results. The study is not positioned to determine how much of the reported LOS was excessive, unnecessary, or preventable. The study findings may not generalize to types of hospitals not contained in PHIS (eg, nonchildren's hospitals and community hospitals). We did not focus on the impact of a new diagnosis (eg, new chronic illness) or acute in‐hospital event (eg, nosocomial infection) on prolonged LOS; future studies should investigate these clinical events with LOS.

PHIS does not contain information regarding characteristics that could influence LOS, including the children's social and familial attributes, transportation availability, home equipment needs, and local availability of postacute care facilities. Moreover, PHIS does not contain information about the hospital discharge procedures, process, or personnel across hospitals, which could influence LOS. Future studies on prolonged LOS should consider assessing this information. Because of the large sample size of hospitalizations included, the statistical power for the analyses was strong, rendering it possible that some findings that were statistically significant might have modest clinical significance (eg, relationship of Hispanic ethnicity with prolonged LOS). We could not determine why a positive correlation was not observed between hospitals' long LOS prevalence and their percentage of cost associated with long LOS; future studies should investigate the reasons for this finding.

Despite these limitations, the findings of the present study highlight the significance of long LOS in hospitalized CMC. These long hospitalizations account for a significant proportion of all hospital costs for this important population of children. The prevalence of long LOS for CMC varies considerably across children's hospitals, even after accounting for the case mix. Efforts to curtail hospital resource use and costs for CMC may benefit from focus on long LOS.