User login

Mental Health Conditions and Unplanned Hospital Readmissions in Children

Readmission prevention is a focus of national efforts to improve the quality of hospital care for children.1-5 Several factors contribute to the risk of readmission for hospitalized children, including age, race or ethnicity, payer, and the type and number of comorbid health conditions.6-9 Mental health conditions (MHCs) are a prevalent comorbidity in children hospitalized for physical health reasons that could influence their postdischarge health and safety.

MHCs are increasingly common in children hospitalized for physical health indications; a comorbid MHC is currently present in 10% to 25% of hospitalized children ages 3 years and older.10,11 Hospital length of stay (LOS) and cost are higher in children with an MHC.12,13 Increased resource use may occur because MHCs can impede hospital treatment effectiveness and the child’s recovery from physical illness. MHCs are associated with a lower adherence with medications14-16 and a lower ability to cope with health events and problems.17-19 In adults, MHCs are a well-established risk factor for hospital readmission for a variety of physical health conditions.20-24 Although the influence of MHCs on readmissions in children has not been extensively investigated, higher readmission rates have been reported in adolescents hospitalized for diabetes with an MHC compared with those with no MHC.25,26

To our knowledge, no large studies have examined the relationship between the presence of a comorbid MHC and hospital readmissions in children or adolescents hospitalized for a broad array of medical or procedure conditions. Therefore, we conducted this study to (1) assess the likelihood of 30-day hospital readmission in children with versus without MHC who were hospitalized for one of 10 medical or 10 procedure conditions, and (2) to assess which MHCs are associated with the highest likelihood of hospital readmission.

METHODS

Study Design and Setting

We conducted a national, retrospective cohort study of index hospitalizations for children ages 3 to 21 years who were discharged from January 1, 2013, to November 30, 2013, in the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s (AHRQ) Nationwide Readmissions Database (NRD). Admissions occurring in December 2013 were excluded because they did not have a 30-day timeframe available for readmission measurement. The 2013 NRD includes administrative data for a nationally representative sample of 14 million hospitalizations in 21 states, accounting for 49% of all US hospitalizations and weighted to represent 35.6 million hospitalizations. The database includes deidentified, verified patient linkage numbers so that patients can be tracked across multiple hospitalizations at the same institution or different institutions within a state. The NRD includes hospital information, patient demographic information, and the International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision-Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) discharge diagnoses and procedures, with 1 primary diagnosis and up to 24 additional fields for comorbid diagnoses. This study was approved for exemption by the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia Institutional Review Board.

Index Admissions

We used the methods described below to create a study cohort of the 10 medical and 10 procedure index admissions associated with the highest volume (ie, the greatest absolute number) of 30-day hospital readmissions. Conditions with a high volume of readmissions were chosen in an effort to identify conditions in which readmission-prevention interventions had the greatest potential to reduce the absolute number of readmissions. We first categorized index hospitalizations for medical and procedure conditions by using the All Patient Refined Diagnosis Related Groups (APR-DRGs; 3M Health Information Systems, Wallingford, CT).27 APR-DRGs use all diagnosis and/or procedure ICD-9-CM codes registered for a hospital discharge to assign 1 reason that best explains the need for hospitalization. We then excluded obstetric hospitalizations, psychiatric hospitalizations, and hospitalizations resulting in death or transfer from being considered as index admissions. Afterwards, we ranked each APR-DRG index hospitalization by the total number of 30-day hospital readmissions that occurred afterward and selected the 10 medical and 10 procedure index admissions with the highest number of readmissions. The APR-DRG index admissions are listed in Figures 1 and 2. For the APR-DRG “digestive system diagnoses,” the most common diagnosis was constipation, and we refer to that category as “constipation.” The most common diagnosis for the APR-DRG called “other operating room procedure for neoplasm” was tumor biopsy, and we refer to that category as “tumor biopsy.”

Main Outcome Measure

The primary study outcome was unplanned, all-cause readmission to any hospital within 30 days of index hospitalization. All-cause readmissions include any hospitalization for the same or different condition as the index admission, including conditions not eligible to be considered as index admissions (obstetric, psychiatric, and hospitalizations resulting in death or transfer). Planned readmissions, identified by using pediatric-specific measure specifications endorsed by AHRQ and the National Quality Forum,28 were excluded from measurement. For index admissions with multiple 30-day readmissions, only the first readmission was counted. Each readmission was treated as an index admission.

Main Independent Variable

The main independent variable was the presence of an MHC documented during the index hospitalization. MHCs were identified and classified into diagnosis categories derived from the AHRQ Chronic Condition Indicator system by using ICD-9-CM codes.29 MHC categories included anxiety disorders, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), autism, depression, and substance abuse. Less common MHCs included bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, disruptive behavior disorders, somatoform disorders, and eating disorders. These conditions are included in the group with any MHC, but we did not calculate the adjusted odds ratios (AORs) of readmission for these conditions. Children were identified as having multiple MHCs if they had more than 1 MHC.

Other Characteristics of Index Hospitalizations

A priori, we selected for analysis the known demographic, clinical, and hospital factors associated with the risk of readmission.20-24 The demographic characteristics included patient age, gender, payer category, urban or rural residence, and the median income quartile for a patient’s ZIP code. The hospital characteristics included location, ownership, and teaching hospital designation. The clinical characteristics included the number of chronic conditions30 and indicators for the presence of a complex chronic condition in each of 12 organ systems.31

Statistical Analysis

We calculated descriptive summary statistics for the characteristics of index hospitalizations. We compared characteristics in index admissions of children with versus without MHC by using Wilcoxon Rank-Sum tests for continuous variables and Wald χ2 tests for categorical variables. In the multivariable analysis, we derived logistic regression models to assess the relationship of 30-day hospital readmission with each type of MHC, adjusting for index admission demographic, hospital, and clinical characteristics. MHCs were modeled as binary indicator variables with the presence of any MHC, more than 1 MHC, or each of 5 MHC categories (anxiety disorders, ADHD, autism, depression, substance abuse) compared with no MHC. Four types of logistic regression models were derived (1) for the combined sample of all 10 index medical admissions with each MHC category versus no MHC as a primary predictor, (2) for each medical index admission with any MHC versus no MHC as the primary predictor, (3) for the combined sample of all 10 index procedure admissions with each MHC category versus no MHC as a primary predictor, and (4) for each procedure index admission with any MHC versus no MHC as the primary predictor. All analyses were weighted to achieve national estimates and clustered by hospital by using AHRQ-recommended survey procedures. SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) was used for all analyses. All tests were two-sided, and a P < .05 was

considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Study Population

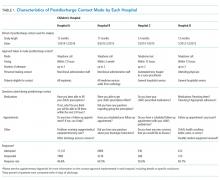

Across all index admissions, 16.3% were for children with an MHC. Overall, children with MHCs were older and more likely to have a chronic30 or complex chronic31 physical health condition than children with no MHCs (Table).

Index Medical Admissions, Mental Health Conditions, and Hospital Readmission

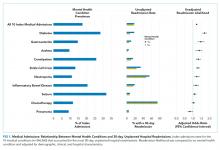

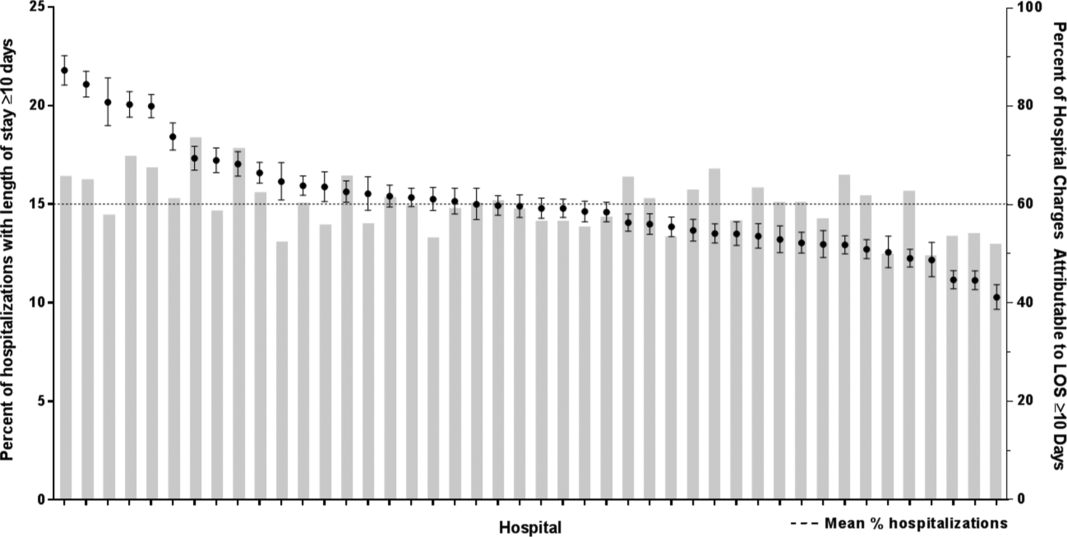

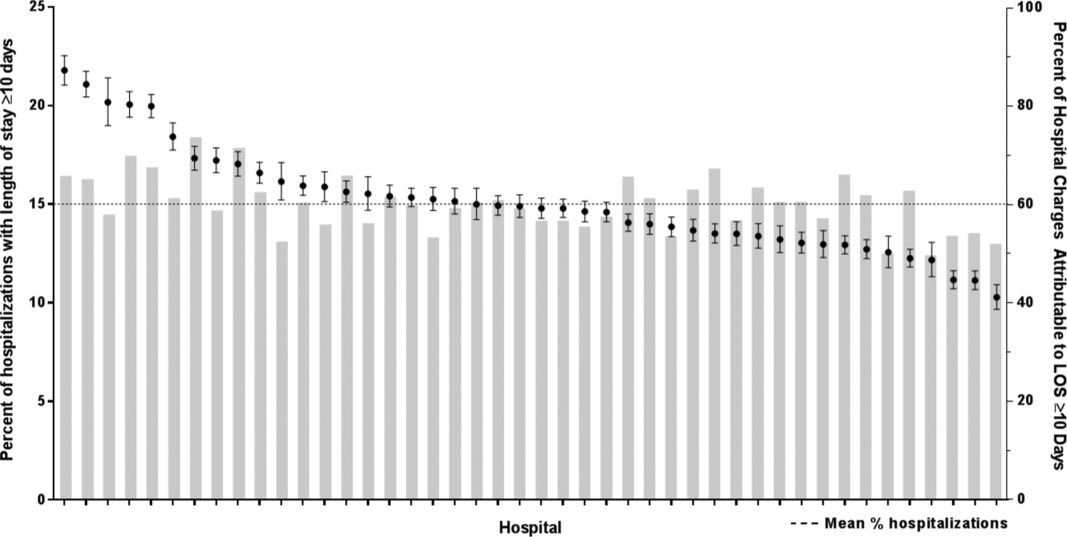

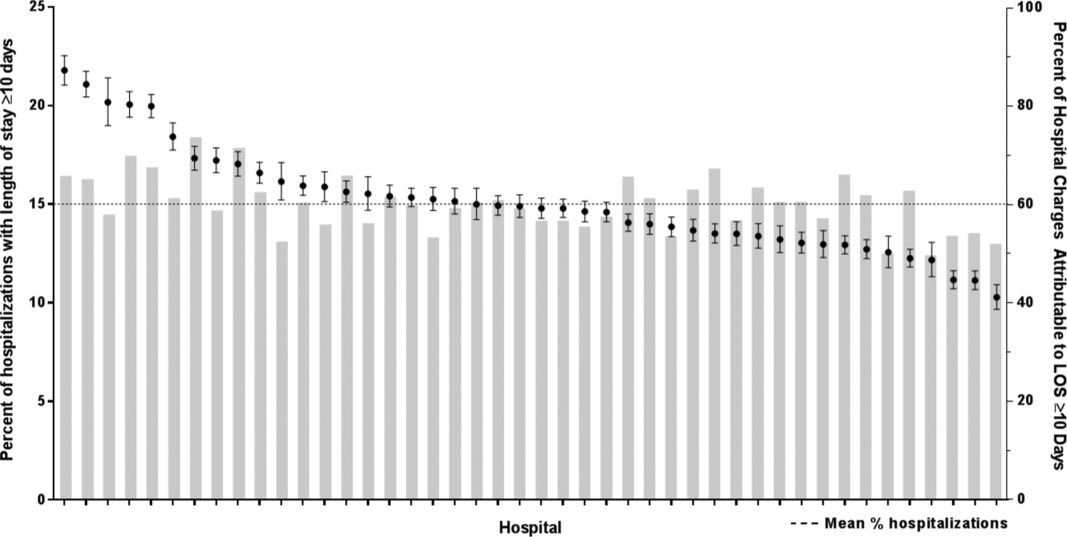

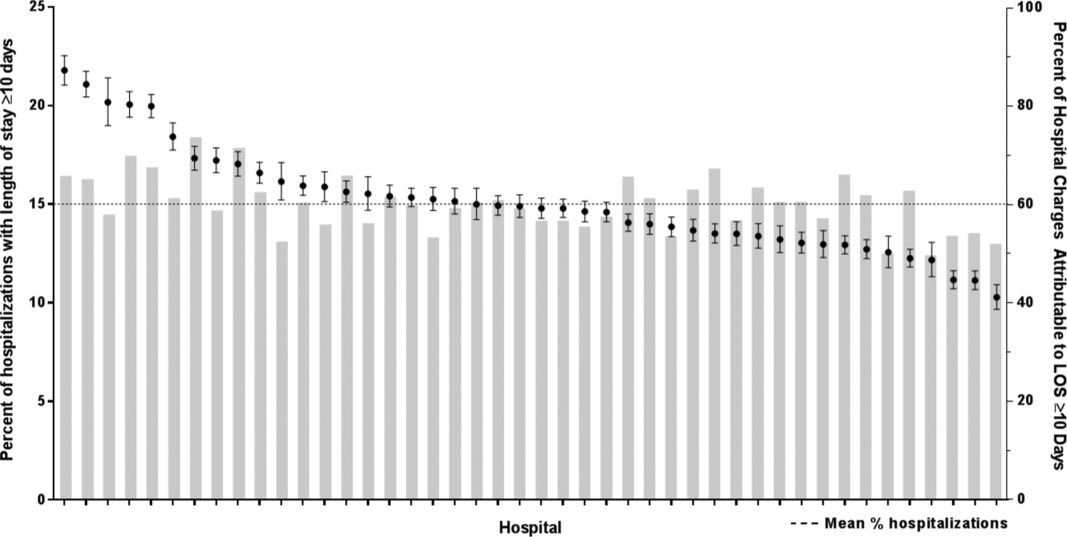

The 10 index medical hospitalizations with the most readmissions for children ages 3 to 20 years were asthma, chemotherapy, constipation, diabetes, gastroenteritis, inflammatory bowel disease, neutropenia, pneumonia, seizure, and sickle cell crisis. Across all index medical hospitalizations, 17.5% were for patients with an MHC (Figure 1). Of index medical admissions with any MHC, 26.3% had ADHD, 22.9% had an anxiety disorder, 14.9% had autism, 18.3% had depression, and 30.9% had substance abuse. Among all admissions with MHCs, 28.9% had 2 or more MHCs.

Index Medical Admissions Combined

For all index medical hospitalizations combined, 17.0% (n = 59,138) had an unplanned, 30-day hospital readmission. The rate of 30-day hospital readmissions was higher with versus without an MHC (17.5 vs 16.8%; P < .001). In a multivariable analysis, presence of an MHC was associated with a higher likelihood of hospital readmission following an index medical admission (AOR, 1.23; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.19-1.26); Figure 1). All MHCs except autism and ADHD had a higher likelihood of readmission (Figure 3).

Specific Index Medical Admissions

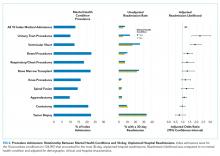

Index Procedure Admissions, Mental Health Conditions, and Hospital Readmission

Index Procedure Admissions Combined

Specific Index Procedure Admissions

For specific index procedure admissions, the rate of 30-day hospital readmission ranged from 2.2% for knee procedures to 33.6% for tumor biopsy. For 3 (ie, urinary tract, ventricular shunt, and bowel procedures) of the 10 specific index procedure hospitalizations, having an MHC was associated with higher adjusted odds of 30-day readmission (AOR range, 1.38-2.27; Figure 2).

In total, adjusting for sociodemographic, clinical, and hospital characteristics, MHCs were associated with an additional 2501 medical readmissions and 217 procedure readmissions beyond what would have been expected if MHCs were not associated with readmissions.

DISCUSSION

MHCs are common among pediatric hospitalizations with the highest volume of readmissions; MHCs were present in approximately 1 in 5 medical and 1 in 7 procedure index hospitalizations. Across medical and procedure admissions, the adjusted likelihood of unplanned, all-cause 30-day readmission was 25% higher for children with versus without an MHC. The readmission likelihood varied by the type of medical or procedure admission and by the type of MHC. MHCs had the strongest associations with readmissions following hospitalization for diabetes and urinary tract procedures. The MHC categories associated with the highest readmission likelihood were depression, substance abuse, and multiple MHCs.

The current study complements existing literature by helping establish MHCs as a prevalent and important risk factor for hospital readmission in children. Estimates of the prevalence of MHCs in hospitalized children are between 10% and 25%,10,11,32 and prevalence has increased by as much as 160% over the last 10 years.29 Prior investigations have found that children with an MHC tend to stay longer in the hospital compared with children with no MHC.32 Results from the present study suggest that children with MHCs also experience more inpatient days because of rehospitalizations. Subsequent investigations should strive to understand the mechanisms in the hospital, community, and family environment that are responsible for the increased inpatient utilization in children with MHCs. Understanding how the receipt of mental health services before, during, and after hospitalization influences readmissions could help identify opportunities for practice improvement. Families report the need for better coordination of their child’s medical and mental health care,33 and opportunities exist to improve attendance at mental health visits after acute care encounters.34 Among adults, interventions that address posthospital access to mental healthcare have prevented readmissions.35

Depression was associated with an increased risk of readmission in medical and procedure hospitalizations. As a well-known risk factor for readmission in adult patients,21 depression can adversely affect and exacerbate the physical health recovery of patients experiencing acute and chronic illnesses.14,36,37 Depression is considered a modifiable contributor that, when controlled, may help lower readmission risk. Optimal adherence with behavior and medication treatment for depression is associated with a lower risk of unplanned 30-day readmissions.14-16,19 Emerging evidence demonstrates how multifaceted, psychosocial approaches can improve patients’ adherence with depression treatment plans.38 Increased attention to depression in hospitalized children may uncover new ways to manage symptoms as children transition from hospital to home.

Other MHCs were associated with a different risk of readmission among medical and procedure hospitalizations. For example, ADHD or autism documented during index hospitalization was associated with an increased risk of readmission following procedure hospitalizations and a decreased risk following medical hospitalizations. Perhaps children with ADHD or autism who exhibit hyperactive, impulsive, or repetitive behaviors39,40 are at risk for disrupting their postprocedure wound healing, nutrition recovery, or pain tolerance, which might contribute to increased readmission risk.

MHCs were associated with different readmission risks across specific types of medical or procedure hospitalizations. For example, among medical conditions, the association of readmissions with MHCs was highest for diabetes, which is consistent with prior research.26 Factors that might mediate this relationship include changes in diet and appetite, difficulty with diabetes care plan adherence, and intentional nonadherence as a form of self-harm. Similarly, a higher risk of readmission in chronic medical conditions like asthma, constipation, and sickle cell disease might be mediated by difficulty adhering to medical plans or managing exacerbations at home. In contrast, MHCs had no association with readmission following chemotherapy. In our clinical experience, readmissions following chemotherapy are driven by physiologic problems, such as thrombocytopenia, fever, and/or neutropenia. MHCs might have limited influence over those health issues. For procedure hospitalizations, MHCs had 1 of the strongest associations with ventricular shunt procedures. We hypothesize that MHCs might lead some children to experience general health symptoms that might be associated with shunt malfunction (eg, fatigue, headache, behavior change), which could lead to an increased risk of readmission to evaluate for shunt malfunction. Conversely, we found no relationship between MHCs and readmissions following appendectomy. For appendectomy, MHCs might have limited influence over the development of postsurgical complications (eg, wound infection or ileus). Future research to better elucidate mediators of increased risk of readmission associated with MHCs in certain medical and procedure conditions could help explain these relationships and identify possible future intervention targets to prevent readmissions.

This study has several limitations. The administrative data are not positioned to discover the mechanisms by which MHCs are associated with a higher likelihood of readmission. We used hospital ICD-9-CM codes to identify patients with MHCs. Other methods using more clinically rich data (eg, chart review, prescription medications, etc.) may be preferable to identify patients with MHCs. Although the use of ICD-9-CM codes may have sufficient specificity, some hospitalized children may have an MHC that is not coded. Patients identified by using diagnosis codes could represent patients with a higher severity of illness, patients using medications, or patients whose outpatient records are accessible to make the hospital team aware of the MHC. If documentation of MHCs during hospitalization represents a higher severity of illness, findings may not extrapolate to lower-severity MHCs. As hospitals transition from ICD-9 -CM to ICD-10 coding, and health systems develop more integrated inpatient and outpatient EHRs, diagnostic specificity may improve. We could not analyze the relationships with several potential confounders and explanatory variables that may be related both to the likelihood of having an MHC and the risk of readmission, including medication administration, psychiatric consultation, and parent mental health. Postdischarge health services, including access to a medical home or a usual source of mental healthcare and measures of medication adherence, were not available in the NRD.

Despite these limitations, the current study underscores the importance of MHCs in hospitalized children upon discharge. As subsequent investigations uncover the key drivers explaining the influence of MHCs on hospital readmission risk, hospitals and their local outpatient and community practices may find it useful to consider MHCs when (1) developing contingency plans and establishing follow-up care at discharge,41 (2) exploring opportunities of care integration between mental and physical health care professionals, and (3) devising strategies to reduce hospital readmissions among populations of children.

CONCLUSIONS

MHCs are prevalent in hospitalized children and are associated with an increased risk of 30-day, unplanned hospital readmission. Future readmission prevention efforts may uncover new ways to improve children’s transitions from hospital to home by investigating strategies to address their MHCs.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Donjo Lau and Troy Richardson for their assistance with the analysis.

Disclosures

Dr. Doupnik was supported by a Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award institutional training grant (T32-HP010026), funded by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Zima was supported by the Behavioral Health Centers of Excellence for California (SB852). Dr. Bardach was supported by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (K23-HD065836). Dr. Berry was supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (R21 HS023092-01). The authors have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose. The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose. Dr. Doupnik led the study design and analysis and drafted the initial manuscript. Mr. Lawlor performed the data analysis. Dr. Hall provided statistical consultation. All authors participated in the design of the study, interpretation of the data, revised the manuscript for key intellectual content, and all authors read and approved the final manuscript.

1. Dougherty D, Schiff J, Mangione-Smith R. The Children’s Health Insurance Program Reauthorization Act quality measures initiatives: moving forward to improve measurement, care, and child and adolescent outcomes. Acad Pediatr. 2011;11(3):S1-S10. PubMed

2. Bardach NS, Vittinghoff E, Asteria-Penaloza R, et al. Measuring Hospital Quality Using Pediatric Readmission and Revisit Rates. Pediatrics. 2013;132(3):429-436. doi:10.1542/peds.2012-3527. PubMed

3. Khan A, Nakamura MM, Zaslavsky AM, et al. Same-Hospital Readmission Rates as a Measure of Pediatric Quality of Care. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169(10):905-912. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.1129. PubMed

4. Fassl BA, Nkoy FL, Stone BL, et al. The Joint Commission Children’s Asthma Care quality measures and asthma readmissions. Pediatrics. 2012;130(3):482-491. doi:10.1542/peds.2011-3318. PubMed

5. Hain PD, Gay JC, Berutti TW, Whitney GM, Wang W, Saville BR. Preventability of Early Readmissions at a Children’s Hospital. Pediatrics. 2013;131(1):e171-e181. doi:10.1542/peds.2012-0820. PubMed

6. Nagasako E, Reidhead B, Waterman B, et al. Adding Socioeconomic Data to Hospital Readmissions Calculations May Produce More Useful Results. Health Aff. 2014;33(5):786-791. PubMed

7. Hu J, Gonsahn MD, Nerenz DR. Socioeconomic Status and Readmissions: Evidence from an Urban Teaching Hospital. Health Aff. 2014;33(5):778-785. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2013.0816. PubMed

8. Sills MR, Hall M, Colvin JD, et al. Association of Social Determinants with Children’s Hospitals’ Preventable Readmissions Performance. JAMA Pediatr. 2016;170(4):350-358. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.4440. PubMed

9. Eselius LL, Cleary PD, Zaslavsky AM, Huskamp HA, Busch SH. Case-Mix Adjustment of Consumer Reports about Managed Behavioral Health Care and Health Plans. Health Serv Res. 2008;43(6):2014-2032. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6773.2008.00894.x. PubMed

10. Doupnik SK, Henry MK, Bae H, et al. Mental Health Conditions and Symptoms in Pediatric Hospitalizations: A Single-Center Point Prevalence Study. Acad Pediatr. 2017;17(2):184-190. PubMed

11. Bardach NS, Coker TR, Zima BT, et al. Common and Costly Hospitalizations for Pediatric Mental Health Disorders. Pediatrics. 2014;133(4):602-609. doi:10.1542/peds.2013-3165. PubMed

12. Doupnik SK, Mitra N, Feudtner C, Marcus SC. The Influence of Comorbid Mood and Anxiety Disorders on Outcomes of Pediatric Patients Hospitalized for Pneumonia. Hosp Pediatr. 2016;6(3):135-142. doi:10.1542/hpeds.2015-0177. PubMed

13. Snell C, Fernandes S, Bujoreanu IS, Garcia G. Depression, illness severity, and healthcare utilization in cystic fibrosis. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2014;49(12):1177-1181. doi:10.1002/ppul.22990. PubMed

14. DiMatteo MR, Lepper HS, Croghan TW. Depression Is a Risk Factor for Noncompliance with Medical Treatment: Meta-analysis of the Effects of Anxiety and Depression on Patient Adherence. Arch Intern Med . 2000;160(14):2101-2107. doi:10.1001/archinte.160.14.2101. PubMed

15. Gray WN, Denson LA, Baldassano RN, Hommel KA. Treatment Adherence in Adolescents with Inflammatory Bowel Disease: The Collective Impact of Barriers to Adherence and Anxiety/Depressive Symptoms. J Pediatr Psychol. 2012;37(3):282-291. doi:10.1093/jpepsy/jsr092. PubMed

16. Mosnaim G, Li H, Martin M, et al. Factors associated with levels of adherence to inhaled corticosteroids in minority adolescents with asthma. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2014;112(2):116-120. doi:10.1016/j.anai.2013.11.021. PubMed

17. Compas BE, Jaser SS, Dunn MJ, Rodriguez EM. Coping with Chronic Illness in Childhood and Adolescence. Ann Rev Clin Psychol. 2012;8(1):455-480. doi:10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032511-143108. PubMed

18. Graue M, Wentzel-Larsen T, Bru E, Hanestad BR, Søvik O. The coping styles of adolescents with type 1 diabetes are associated with degree of metabolic control. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(6):1313-1317. PubMed

19. Jaser SS, White LE. Coping and resilience in adolescents with type 1 diabetes. Child Care Health Dev. 2011;37(3):335-342. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2214.2010.01184.x. PubMed

20. Cancino RS, Culpepper L, Sadikova E, Martin J, Jack BW, Mitchell SE. Dose-response relationship between depressive symptoms and hospital readmission. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(6):358-364. doi:10.1002/jhm.2180. PubMed

21. Pederson JL, Warkentin LM, Majumdar SR, McAlister FA. Depressive symptoms are associated with higher rates of readmission or mortality after medical hospitalization: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(5):373-380. doi:10.1002/jhm.2547. PubMed

22. Chwastiak LA, Davydow DS, McKibbin CL, et al. The Effect of Serious Mental Illness on the Risk of Rehospitalization Among Patients with Diabetes. Psychosomatics. 2014;55(2):134-143. PubMed

23. Daratha KB, Barbosa-Leiker C, H Burley M, et al. Co-occurring mood disorders among hospitalized patients and risk for subsequent medical hospitalization. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2012;34(5):500-505. doi:10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2012.05.001. PubMed

24. Kartha A, Anthony D, Manasseh CS, et al. Depression is a risk factor for rehospitalization in medical inpatients. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;9(4):256-262. PubMed

25. Myrvik MP, Burks LM, Hoffman RG, Dasgupta M, Panepinto JA. Mental health disorders influence admission rates for pain in children with sickle cell disease. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2013;60(7):1211-1214. doi:10.1002/pbc.24394. PubMed

26. Garrison MM, Katon WJ, Richardson LP. The impact of psychiatric comorbidities on readmissions for diabetes in youth. Diabetes Care. 2005;28(9):2150-2154. PubMed

27. Averill R, Goldfield N, Hughes JS, et al. All Patient Refined Diagnosis Related Groups (APR-DRGs) Version 20.0: Methodology Overview. https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/db/nation/nis/APR-DRGsV20MethodologyOverviewandBibliography.pdf. Accessed on November 2, 2016.

28. Berry JG, Toomey SL, Zaslavsky AM, et al. Pediatric readmission prevalence and variability across hospitals. JAMA. 2013;309(4):372-380. PubMed

29. Zima BT, Rodean J, Hall M, Bardach NS, Coker TR, Berry JG. Psychiatric Disorders and Trends in Resource Use in Pediatric Hospitals. Pediatrics. 2016;138(5):e20160909-e20160909. doi:10.1542/peds.2016-0909. PubMed

30. Chronic Condition Indicator (CCI) for ICD-9-CM. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Tools & Software Page. http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/chronic/chronic.jsp. Accessed on October 30, 2015.

31. Feudtner C, Feinstein J, Zhong W, Hall M, Dai D. Pediatric complex chronic conditions classification system version 2: updated for ICD-10 and complex medical technology dependence and transplantation. BMC Pediatr. 2014;14(1):199-205. PubMed

32. Doupnik S, Lawlor J, Zima BT, et al. Mental Health Conditions and Medical and Surgical Hospital Utilization. Pediatrics. 2016;138(6):e20162416. doi:10.1542/peds.2016-2416. PubMed

33. Brown NM, Green JC, Desai MM, Weitzman CC, Rosenthal MS. Need and Unmet Need for Care Coordination Among Children with Mental Health Conditions. Pediatrics. 2014;133(3):e530-e537. doi:10.1542/peds.2013-2590. PubMed

34. Sobolewski B, Richey L, Kowatch RA, Grupp-Phelan J. Mental health follow-up among adolescents with suicidal behaviors after emergency department discharge. Arch Suicide Res. 2013;17(4):323-334. doi:10.1080/13811118.2013.801807. PubMed

35. Hansen LO, Greenwald JL, Budnitz T, et al. Project BOOST: Effectiveness of a multihospital effort to reduce rehospitalization. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(8):421-427. doi:10.1002/jhm.2054. PubMed

36. Di Marco F, Verga M, Santus P, et al. Close correlation between anxiety, depression, and asthma control. Respir Med. 2010;104(1):22-28. doi:10.1016/j.rmed.2009.08.005. PubMed

37. Ghose SS, Williams LS, Swindle RW. Depression and other mental health diagnoses after stroke increase inpatient and outpatient medical utilization three years poststroke. Med Care. 2005;43(12):1259-1264. PubMed

38. Szigethy E, Bujoreanu SI, Youk AO, et al. Randomized efficacy trial of two psychotherapies for depression in youth with inflammatory bowel disease. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2014;53(7):726-735. PubMed

39. Swensen A, Birnbaum HG, Ben Hamadi R, Greenberg P, Cremieux PY, Secnik K. Incidence and costs of accidents among attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder patients. J Adolesc Health. 2004;35(4):346.e1-346.e9. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2003.12.003. PubMed

40. Chan E, Zhan C, Homer CJ. Health Care Use and Costs for Children with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder: National Estimates from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2002;156(5):504-511. doi:10.1001/archpedi.156.5.504. PubMed

41. Berry JG, Blaine K, Rogers J, et al. A Framework of Pediatric Hospital Discharge Care Informed by Legislation, Research, and Practice. JAMA Pediatr. 2014;168(10):955-962. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.891. PubMed

Readmission prevention is a focus of national efforts to improve the quality of hospital care for children.1-5 Several factors contribute to the risk of readmission for hospitalized children, including age, race or ethnicity, payer, and the type and number of comorbid health conditions.6-9 Mental health conditions (MHCs) are a prevalent comorbidity in children hospitalized for physical health reasons that could influence their postdischarge health and safety.

MHCs are increasingly common in children hospitalized for physical health indications; a comorbid MHC is currently present in 10% to 25% of hospitalized children ages 3 years and older.10,11 Hospital length of stay (LOS) and cost are higher in children with an MHC.12,13 Increased resource use may occur because MHCs can impede hospital treatment effectiveness and the child’s recovery from physical illness. MHCs are associated with a lower adherence with medications14-16 and a lower ability to cope with health events and problems.17-19 In adults, MHCs are a well-established risk factor for hospital readmission for a variety of physical health conditions.20-24 Although the influence of MHCs on readmissions in children has not been extensively investigated, higher readmission rates have been reported in adolescents hospitalized for diabetes with an MHC compared with those with no MHC.25,26

To our knowledge, no large studies have examined the relationship between the presence of a comorbid MHC and hospital readmissions in children or adolescents hospitalized for a broad array of medical or procedure conditions. Therefore, we conducted this study to (1) assess the likelihood of 30-day hospital readmission in children with versus without MHC who were hospitalized for one of 10 medical or 10 procedure conditions, and (2) to assess which MHCs are associated with the highest likelihood of hospital readmission.

METHODS

Study Design and Setting

We conducted a national, retrospective cohort study of index hospitalizations for children ages 3 to 21 years who were discharged from January 1, 2013, to November 30, 2013, in the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s (AHRQ) Nationwide Readmissions Database (NRD). Admissions occurring in December 2013 were excluded because they did not have a 30-day timeframe available for readmission measurement. The 2013 NRD includes administrative data for a nationally representative sample of 14 million hospitalizations in 21 states, accounting for 49% of all US hospitalizations and weighted to represent 35.6 million hospitalizations. The database includes deidentified, verified patient linkage numbers so that patients can be tracked across multiple hospitalizations at the same institution or different institutions within a state. The NRD includes hospital information, patient demographic information, and the International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision-Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) discharge diagnoses and procedures, with 1 primary diagnosis and up to 24 additional fields for comorbid diagnoses. This study was approved for exemption by the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia Institutional Review Board.

Index Admissions

We used the methods described below to create a study cohort of the 10 medical and 10 procedure index admissions associated with the highest volume (ie, the greatest absolute number) of 30-day hospital readmissions. Conditions with a high volume of readmissions were chosen in an effort to identify conditions in which readmission-prevention interventions had the greatest potential to reduce the absolute number of readmissions. We first categorized index hospitalizations for medical and procedure conditions by using the All Patient Refined Diagnosis Related Groups (APR-DRGs; 3M Health Information Systems, Wallingford, CT).27 APR-DRGs use all diagnosis and/or procedure ICD-9-CM codes registered for a hospital discharge to assign 1 reason that best explains the need for hospitalization. We then excluded obstetric hospitalizations, psychiatric hospitalizations, and hospitalizations resulting in death or transfer from being considered as index admissions. Afterwards, we ranked each APR-DRG index hospitalization by the total number of 30-day hospital readmissions that occurred afterward and selected the 10 medical and 10 procedure index admissions with the highest number of readmissions. The APR-DRG index admissions are listed in Figures 1 and 2. For the APR-DRG “digestive system diagnoses,” the most common diagnosis was constipation, and we refer to that category as “constipation.” The most common diagnosis for the APR-DRG called “other operating room procedure for neoplasm” was tumor biopsy, and we refer to that category as “tumor biopsy.”

Main Outcome Measure

The primary study outcome was unplanned, all-cause readmission to any hospital within 30 days of index hospitalization. All-cause readmissions include any hospitalization for the same or different condition as the index admission, including conditions not eligible to be considered as index admissions (obstetric, psychiatric, and hospitalizations resulting in death or transfer). Planned readmissions, identified by using pediatric-specific measure specifications endorsed by AHRQ and the National Quality Forum,28 were excluded from measurement. For index admissions with multiple 30-day readmissions, only the first readmission was counted. Each readmission was treated as an index admission.

Main Independent Variable

The main independent variable was the presence of an MHC documented during the index hospitalization. MHCs were identified and classified into diagnosis categories derived from the AHRQ Chronic Condition Indicator system by using ICD-9-CM codes.29 MHC categories included anxiety disorders, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), autism, depression, and substance abuse. Less common MHCs included bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, disruptive behavior disorders, somatoform disorders, and eating disorders. These conditions are included in the group with any MHC, but we did not calculate the adjusted odds ratios (AORs) of readmission for these conditions. Children were identified as having multiple MHCs if they had more than 1 MHC.

Other Characteristics of Index Hospitalizations

A priori, we selected for analysis the known demographic, clinical, and hospital factors associated with the risk of readmission.20-24 The demographic characteristics included patient age, gender, payer category, urban or rural residence, and the median income quartile for a patient’s ZIP code. The hospital characteristics included location, ownership, and teaching hospital designation. The clinical characteristics included the number of chronic conditions30 and indicators for the presence of a complex chronic condition in each of 12 organ systems.31

Statistical Analysis

We calculated descriptive summary statistics for the characteristics of index hospitalizations. We compared characteristics in index admissions of children with versus without MHC by using Wilcoxon Rank-Sum tests for continuous variables and Wald χ2 tests for categorical variables. In the multivariable analysis, we derived logistic regression models to assess the relationship of 30-day hospital readmission with each type of MHC, adjusting for index admission demographic, hospital, and clinical characteristics. MHCs were modeled as binary indicator variables with the presence of any MHC, more than 1 MHC, or each of 5 MHC categories (anxiety disorders, ADHD, autism, depression, substance abuse) compared with no MHC. Four types of logistic regression models were derived (1) for the combined sample of all 10 index medical admissions with each MHC category versus no MHC as a primary predictor, (2) for each medical index admission with any MHC versus no MHC as the primary predictor, (3) for the combined sample of all 10 index procedure admissions with each MHC category versus no MHC as a primary predictor, and (4) for each procedure index admission with any MHC versus no MHC as the primary predictor. All analyses were weighted to achieve national estimates and clustered by hospital by using AHRQ-recommended survey procedures. SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) was used for all analyses. All tests were two-sided, and a P < .05 was

considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Study Population

Across all index admissions, 16.3% were for children with an MHC. Overall, children with MHCs were older and more likely to have a chronic30 or complex chronic31 physical health condition than children with no MHCs (Table).

Index Medical Admissions, Mental Health Conditions, and Hospital Readmission

The 10 index medical hospitalizations with the most readmissions for children ages 3 to 20 years were asthma, chemotherapy, constipation, diabetes, gastroenteritis, inflammatory bowel disease, neutropenia, pneumonia, seizure, and sickle cell crisis. Across all index medical hospitalizations, 17.5% were for patients with an MHC (Figure 1). Of index medical admissions with any MHC, 26.3% had ADHD, 22.9% had an anxiety disorder, 14.9% had autism, 18.3% had depression, and 30.9% had substance abuse. Among all admissions with MHCs, 28.9% had 2 or more MHCs.

Index Medical Admissions Combined

For all index medical hospitalizations combined, 17.0% (n = 59,138) had an unplanned, 30-day hospital readmission. The rate of 30-day hospital readmissions was higher with versus without an MHC (17.5 vs 16.8%; P < .001). In a multivariable analysis, presence of an MHC was associated with a higher likelihood of hospital readmission following an index medical admission (AOR, 1.23; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.19-1.26); Figure 1). All MHCs except autism and ADHD had a higher likelihood of readmission (Figure 3).

Specific Index Medical Admissions

Index Procedure Admissions, Mental Health Conditions, and Hospital Readmission

Index Procedure Admissions Combined

Specific Index Procedure Admissions

For specific index procedure admissions, the rate of 30-day hospital readmission ranged from 2.2% for knee procedures to 33.6% for tumor biopsy. For 3 (ie, urinary tract, ventricular shunt, and bowel procedures) of the 10 specific index procedure hospitalizations, having an MHC was associated with higher adjusted odds of 30-day readmission (AOR range, 1.38-2.27; Figure 2).

In total, adjusting for sociodemographic, clinical, and hospital characteristics, MHCs were associated with an additional 2501 medical readmissions and 217 procedure readmissions beyond what would have been expected if MHCs were not associated with readmissions.

DISCUSSION

MHCs are common among pediatric hospitalizations with the highest volume of readmissions; MHCs were present in approximately 1 in 5 medical and 1 in 7 procedure index hospitalizations. Across medical and procedure admissions, the adjusted likelihood of unplanned, all-cause 30-day readmission was 25% higher for children with versus without an MHC. The readmission likelihood varied by the type of medical or procedure admission and by the type of MHC. MHCs had the strongest associations with readmissions following hospitalization for diabetes and urinary tract procedures. The MHC categories associated with the highest readmission likelihood were depression, substance abuse, and multiple MHCs.

The current study complements existing literature by helping establish MHCs as a prevalent and important risk factor for hospital readmission in children. Estimates of the prevalence of MHCs in hospitalized children are between 10% and 25%,10,11,32 and prevalence has increased by as much as 160% over the last 10 years.29 Prior investigations have found that children with an MHC tend to stay longer in the hospital compared with children with no MHC.32 Results from the present study suggest that children with MHCs also experience more inpatient days because of rehospitalizations. Subsequent investigations should strive to understand the mechanisms in the hospital, community, and family environment that are responsible for the increased inpatient utilization in children with MHCs. Understanding how the receipt of mental health services before, during, and after hospitalization influences readmissions could help identify opportunities for practice improvement. Families report the need for better coordination of their child’s medical and mental health care,33 and opportunities exist to improve attendance at mental health visits after acute care encounters.34 Among adults, interventions that address posthospital access to mental healthcare have prevented readmissions.35

Depression was associated with an increased risk of readmission in medical and procedure hospitalizations. As a well-known risk factor for readmission in adult patients,21 depression can adversely affect and exacerbate the physical health recovery of patients experiencing acute and chronic illnesses.14,36,37 Depression is considered a modifiable contributor that, when controlled, may help lower readmission risk. Optimal adherence with behavior and medication treatment for depression is associated with a lower risk of unplanned 30-day readmissions.14-16,19 Emerging evidence demonstrates how multifaceted, psychosocial approaches can improve patients’ adherence with depression treatment plans.38 Increased attention to depression in hospitalized children may uncover new ways to manage symptoms as children transition from hospital to home.

Other MHCs were associated with a different risk of readmission among medical and procedure hospitalizations. For example, ADHD or autism documented during index hospitalization was associated with an increased risk of readmission following procedure hospitalizations and a decreased risk following medical hospitalizations. Perhaps children with ADHD or autism who exhibit hyperactive, impulsive, or repetitive behaviors39,40 are at risk for disrupting their postprocedure wound healing, nutrition recovery, or pain tolerance, which might contribute to increased readmission risk.

MHCs were associated with different readmission risks across specific types of medical or procedure hospitalizations. For example, among medical conditions, the association of readmissions with MHCs was highest for diabetes, which is consistent with prior research.26 Factors that might mediate this relationship include changes in diet and appetite, difficulty with diabetes care plan adherence, and intentional nonadherence as a form of self-harm. Similarly, a higher risk of readmission in chronic medical conditions like asthma, constipation, and sickle cell disease might be mediated by difficulty adhering to medical plans or managing exacerbations at home. In contrast, MHCs had no association with readmission following chemotherapy. In our clinical experience, readmissions following chemotherapy are driven by physiologic problems, such as thrombocytopenia, fever, and/or neutropenia. MHCs might have limited influence over those health issues. For procedure hospitalizations, MHCs had 1 of the strongest associations with ventricular shunt procedures. We hypothesize that MHCs might lead some children to experience general health symptoms that might be associated with shunt malfunction (eg, fatigue, headache, behavior change), which could lead to an increased risk of readmission to evaluate for shunt malfunction. Conversely, we found no relationship between MHCs and readmissions following appendectomy. For appendectomy, MHCs might have limited influence over the development of postsurgical complications (eg, wound infection or ileus). Future research to better elucidate mediators of increased risk of readmission associated with MHCs in certain medical and procedure conditions could help explain these relationships and identify possible future intervention targets to prevent readmissions.

This study has several limitations. The administrative data are not positioned to discover the mechanisms by which MHCs are associated with a higher likelihood of readmission. We used hospital ICD-9-CM codes to identify patients with MHCs. Other methods using more clinically rich data (eg, chart review, prescription medications, etc.) may be preferable to identify patients with MHCs. Although the use of ICD-9-CM codes may have sufficient specificity, some hospitalized children may have an MHC that is not coded. Patients identified by using diagnosis codes could represent patients with a higher severity of illness, patients using medications, or patients whose outpatient records are accessible to make the hospital team aware of the MHC. If documentation of MHCs during hospitalization represents a higher severity of illness, findings may not extrapolate to lower-severity MHCs. As hospitals transition from ICD-9 -CM to ICD-10 coding, and health systems develop more integrated inpatient and outpatient EHRs, diagnostic specificity may improve. We could not analyze the relationships with several potential confounders and explanatory variables that may be related both to the likelihood of having an MHC and the risk of readmission, including medication administration, psychiatric consultation, and parent mental health. Postdischarge health services, including access to a medical home or a usual source of mental healthcare and measures of medication adherence, were not available in the NRD.

Despite these limitations, the current study underscores the importance of MHCs in hospitalized children upon discharge. As subsequent investigations uncover the key drivers explaining the influence of MHCs on hospital readmission risk, hospitals and their local outpatient and community practices may find it useful to consider MHCs when (1) developing contingency plans and establishing follow-up care at discharge,41 (2) exploring opportunities of care integration between mental and physical health care professionals, and (3) devising strategies to reduce hospital readmissions among populations of children.

CONCLUSIONS

MHCs are prevalent in hospitalized children and are associated with an increased risk of 30-day, unplanned hospital readmission. Future readmission prevention efforts may uncover new ways to improve children’s transitions from hospital to home by investigating strategies to address their MHCs.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Donjo Lau and Troy Richardson for their assistance with the analysis.

Disclosures

Dr. Doupnik was supported by a Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award institutional training grant (T32-HP010026), funded by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Zima was supported by the Behavioral Health Centers of Excellence for California (SB852). Dr. Bardach was supported by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (K23-HD065836). Dr. Berry was supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (R21 HS023092-01). The authors have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose. The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose. Dr. Doupnik led the study design and analysis and drafted the initial manuscript. Mr. Lawlor performed the data analysis. Dr. Hall provided statistical consultation. All authors participated in the design of the study, interpretation of the data, revised the manuscript for key intellectual content, and all authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Readmission prevention is a focus of national efforts to improve the quality of hospital care for children.1-5 Several factors contribute to the risk of readmission for hospitalized children, including age, race or ethnicity, payer, and the type and number of comorbid health conditions.6-9 Mental health conditions (MHCs) are a prevalent comorbidity in children hospitalized for physical health reasons that could influence their postdischarge health and safety.

MHCs are increasingly common in children hospitalized for physical health indications; a comorbid MHC is currently present in 10% to 25% of hospitalized children ages 3 years and older.10,11 Hospital length of stay (LOS) and cost are higher in children with an MHC.12,13 Increased resource use may occur because MHCs can impede hospital treatment effectiveness and the child’s recovery from physical illness. MHCs are associated with a lower adherence with medications14-16 and a lower ability to cope with health events and problems.17-19 In adults, MHCs are a well-established risk factor for hospital readmission for a variety of physical health conditions.20-24 Although the influence of MHCs on readmissions in children has not been extensively investigated, higher readmission rates have been reported in adolescents hospitalized for diabetes with an MHC compared with those with no MHC.25,26

To our knowledge, no large studies have examined the relationship between the presence of a comorbid MHC and hospital readmissions in children or adolescents hospitalized for a broad array of medical or procedure conditions. Therefore, we conducted this study to (1) assess the likelihood of 30-day hospital readmission in children with versus without MHC who were hospitalized for one of 10 medical or 10 procedure conditions, and (2) to assess which MHCs are associated with the highest likelihood of hospital readmission.

METHODS

Study Design and Setting

We conducted a national, retrospective cohort study of index hospitalizations for children ages 3 to 21 years who were discharged from January 1, 2013, to November 30, 2013, in the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s (AHRQ) Nationwide Readmissions Database (NRD). Admissions occurring in December 2013 were excluded because they did not have a 30-day timeframe available for readmission measurement. The 2013 NRD includes administrative data for a nationally representative sample of 14 million hospitalizations in 21 states, accounting for 49% of all US hospitalizations and weighted to represent 35.6 million hospitalizations. The database includes deidentified, verified patient linkage numbers so that patients can be tracked across multiple hospitalizations at the same institution or different institutions within a state. The NRD includes hospital information, patient demographic information, and the International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision-Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) discharge diagnoses and procedures, with 1 primary diagnosis and up to 24 additional fields for comorbid diagnoses. This study was approved for exemption by the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia Institutional Review Board.

Index Admissions

We used the methods described below to create a study cohort of the 10 medical and 10 procedure index admissions associated with the highest volume (ie, the greatest absolute number) of 30-day hospital readmissions. Conditions with a high volume of readmissions were chosen in an effort to identify conditions in which readmission-prevention interventions had the greatest potential to reduce the absolute number of readmissions. We first categorized index hospitalizations for medical and procedure conditions by using the All Patient Refined Diagnosis Related Groups (APR-DRGs; 3M Health Information Systems, Wallingford, CT).27 APR-DRGs use all diagnosis and/or procedure ICD-9-CM codes registered for a hospital discharge to assign 1 reason that best explains the need for hospitalization. We then excluded obstetric hospitalizations, psychiatric hospitalizations, and hospitalizations resulting in death or transfer from being considered as index admissions. Afterwards, we ranked each APR-DRG index hospitalization by the total number of 30-day hospital readmissions that occurred afterward and selected the 10 medical and 10 procedure index admissions with the highest number of readmissions. The APR-DRG index admissions are listed in Figures 1 and 2. For the APR-DRG “digestive system diagnoses,” the most common diagnosis was constipation, and we refer to that category as “constipation.” The most common diagnosis for the APR-DRG called “other operating room procedure for neoplasm” was tumor biopsy, and we refer to that category as “tumor biopsy.”

Main Outcome Measure

The primary study outcome was unplanned, all-cause readmission to any hospital within 30 days of index hospitalization. All-cause readmissions include any hospitalization for the same or different condition as the index admission, including conditions not eligible to be considered as index admissions (obstetric, psychiatric, and hospitalizations resulting in death or transfer). Planned readmissions, identified by using pediatric-specific measure specifications endorsed by AHRQ and the National Quality Forum,28 were excluded from measurement. For index admissions with multiple 30-day readmissions, only the first readmission was counted. Each readmission was treated as an index admission.

Main Independent Variable

The main independent variable was the presence of an MHC documented during the index hospitalization. MHCs were identified and classified into diagnosis categories derived from the AHRQ Chronic Condition Indicator system by using ICD-9-CM codes.29 MHC categories included anxiety disorders, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), autism, depression, and substance abuse. Less common MHCs included bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, disruptive behavior disorders, somatoform disorders, and eating disorders. These conditions are included in the group with any MHC, but we did not calculate the adjusted odds ratios (AORs) of readmission for these conditions. Children were identified as having multiple MHCs if they had more than 1 MHC.

Other Characteristics of Index Hospitalizations

A priori, we selected for analysis the known demographic, clinical, and hospital factors associated with the risk of readmission.20-24 The demographic characteristics included patient age, gender, payer category, urban or rural residence, and the median income quartile for a patient’s ZIP code. The hospital characteristics included location, ownership, and teaching hospital designation. The clinical characteristics included the number of chronic conditions30 and indicators for the presence of a complex chronic condition in each of 12 organ systems.31

Statistical Analysis

We calculated descriptive summary statistics for the characteristics of index hospitalizations. We compared characteristics in index admissions of children with versus without MHC by using Wilcoxon Rank-Sum tests for continuous variables and Wald χ2 tests for categorical variables. In the multivariable analysis, we derived logistic regression models to assess the relationship of 30-day hospital readmission with each type of MHC, adjusting for index admission demographic, hospital, and clinical characteristics. MHCs were modeled as binary indicator variables with the presence of any MHC, more than 1 MHC, or each of 5 MHC categories (anxiety disorders, ADHD, autism, depression, substance abuse) compared with no MHC. Four types of logistic regression models were derived (1) for the combined sample of all 10 index medical admissions with each MHC category versus no MHC as a primary predictor, (2) for each medical index admission with any MHC versus no MHC as the primary predictor, (3) for the combined sample of all 10 index procedure admissions with each MHC category versus no MHC as a primary predictor, and (4) for each procedure index admission with any MHC versus no MHC as the primary predictor. All analyses were weighted to achieve national estimates and clustered by hospital by using AHRQ-recommended survey procedures. SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) was used for all analyses. All tests were two-sided, and a P < .05 was

considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Study Population

Across all index admissions, 16.3% were for children with an MHC. Overall, children with MHCs were older and more likely to have a chronic30 or complex chronic31 physical health condition than children with no MHCs (Table).

Index Medical Admissions, Mental Health Conditions, and Hospital Readmission

The 10 index medical hospitalizations with the most readmissions for children ages 3 to 20 years were asthma, chemotherapy, constipation, diabetes, gastroenteritis, inflammatory bowel disease, neutropenia, pneumonia, seizure, and sickle cell crisis. Across all index medical hospitalizations, 17.5% were for patients with an MHC (Figure 1). Of index medical admissions with any MHC, 26.3% had ADHD, 22.9% had an anxiety disorder, 14.9% had autism, 18.3% had depression, and 30.9% had substance abuse. Among all admissions with MHCs, 28.9% had 2 or more MHCs.

Index Medical Admissions Combined

For all index medical hospitalizations combined, 17.0% (n = 59,138) had an unplanned, 30-day hospital readmission. The rate of 30-day hospital readmissions was higher with versus without an MHC (17.5 vs 16.8%; P < .001). In a multivariable analysis, presence of an MHC was associated with a higher likelihood of hospital readmission following an index medical admission (AOR, 1.23; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.19-1.26); Figure 1). All MHCs except autism and ADHD had a higher likelihood of readmission (Figure 3).

Specific Index Medical Admissions

Index Procedure Admissions, Mental Health Conditions, and Hospital Readmission

Index Procedure Admissions Combined

Specific Index Procedure Admissions

For specific index procedure admissions, the rate of 30-day hospital readmission ranged from 2.2% for knee procedures to 33.6% for tumor biopsy. For 3 (ie, urinary tract, ventricular shunt, and bowel procedures) of the 10 specific index procedure hospitalizations, having an MHC was associated with higher adjusted odds of 30-day readmission (AOR range, 1.38-2.27; Figure 2).

In total, adjusting for sociodemographic, clinical, and hospital characteristics, MHCs were associated with an additional 2501 medical readmissions and 217 procedure readmissions beyond what would have been expected if MHCs were not associated with readmissions.

DISCUSSION

MHCs are common among pediatric hospitalizations with the highest volume of readmissions; MHCs were present in approximately 1 in 5 medical and 1 in 7 procedure index hospitalizations. Across medical and procedure admissions, the adjusted likelihood of unplanned, all-cause 30-day readmission was 25% higher for children with versus without an MHC. The readmission likelihood varied by the type of medical or procedure admission and by the type of MHC. MHCs had the strongest associations with readmissions following hospitalization for diabetes and urinary tract procedures. The MHC categories associated with the highest readmission likelihood were depression, substance abuse, and multiple MHCs.

The current study complements existing literature by helping establish MHCs as a prevalent and important risk factor for hospital readmission in children. Estimates of the prevalence of MHCs in hospitalized children are between 10% and 25%,10,11,32 and prevalence has increased by as much as 160% over the last 10 years.29 Prior investigations have found that children with an MHC tend to stay longer in the hospital compared with children with no MHC.32 Results from the present study suggest that children with MHCs also experience more inpatient days because of rehospitalizations. Subsequent investigations should strive to understand the mechanisms in the hospital, community, and family environment that are responsible for the increased inpatient utilization in children with MHCs. Understanding how the receipt of mental health services before, during, and after hospitalization influences readmissions could help identify opportunities for practice improvement. Families report the need for better coordination of their child’s medical and mental health care,33 and opportunities exist to improve attendance at mental health visits after acute care encounters.34 Among adults, interventions that address posthospital access to mental healthcare have prevented readmissions.35

Depression was associated with an increased risk of readmission in medical and procedure hospitalizations. As a well-known risk factor for readmission in adult patients,21 depression can adversely affect and exacerbate the physical health recovery of patients experiencing acute and chronic illnesses.14,36,37 Depression is considered a modifiable contributor that, when controlled, may help lower readmission risk. Optimal adherence with behavior and medication treatment for depression is associated with a lower risk of unplanned 30-day readmissions.14-16,19 Emerging evidence demonstrates how multifaceted, psychosocial approaches can improve patients’ adherence with depression treatment plans.38 Increased attention to depression in hospitalized children may uncover new ways to manage symptoms as children transition from hospital to home.

Other MHCs were associated with a different risk of readmission among medical and procedure hospitalizations. For example, ADHD or autism documented during index hospitalization was associated with an increased risk of readmission following procedure hospitalizations and a decreased risk following medical hospitalizations. Perhaps children with ADHD or autism who exhibit hyperactive, impulsive, or repetitive behaviors39,40 are at risk for disrupting their postprocedure wound healing, nutrition recovery, or pain tolerance, which might contribute to increased readmission risk.

MHCs were associated with different readmission risks across specific types of medical or procedure hospitalizations. For example, among medical conditions, the association of readmissions with MHCs was highest for diabetes, which is consistent with prior research.26 Factors that might mediate this relationship include changes in diet and appetite, difficulty with diabetes care plan adherence, and intentional nonadherence as a form of self-harm. Similarly, a higher risk of readmission in chronic medical conditions like asthma, constipation, and sickle cell disease might be mediated by difficulty adhering to medical plans or managing exacerbations at home. In contrast, MHCs had no association with readmission following chemotherapy. In our clinical experience, readmissions following chemotherapy are driven by physiologic problems, such as thrombocytopenia, fever, and/or neutropenia. MHCs might have limited influence over those health issues. For procedure hospitalizations, MHCs had 1 of the strongest associations with ventricular shunt procedures. We hypothesize that MHCs might lead some children to experience general health symptoms that might be associated with shunt malfunction (eg, fatigue, headache, behavior change), which could lead to an increased risk of readmission to evaluate for shunt malfunction. Conversely, we found no relationship between MHCs and readmissions following appendectomy. For appendectomy, MHCs might have limited influence over the development of postsurgical complications (eg, wound infection or ileus). Future research to better elucidate mediators of increased risk of readmission associated with MHCs in certain medical and procedure conditions could help explain these relationships and identify possible future intervention targets to prevent readmissions.

This study has several limitations. The administrative data are not positioned to discover the mechanisms by which MHCs are associated with a higher likelihood of readmission. We used hospital ICD-9-CM codes to identify patients with MHCs. Other methods using more clinically rich data (eg, chart review, prescription medications, etc.) may be preferable to identify patients with MHCs. Although the use of ICD-9-CM codes may have sufficient specificity, some hospitalized children may have an MHC that is not coded. Patients identified by using diagnosis codes could represent patients with a higher severity of illness, patients using medications, or patients whose outpatient records are accessible to make the hospital team aware of the MHC. If documentation of MHCs during hospitalization represents a higher severity of illness, findings may not extrapolate to lower-severity MHCs. As hospitals transition from ICD-9 -CM to ICD-10 coding, and health systems develop more integrated inpatient and outpatient EHRs, diagnostic specificity may improve. We could not analyze the relationships with several potential confounders and explanatory variables that may be related both to the likelihood of having an MHC and the risk of readmission, including medication administration, psychiatric consultation, and parent mental health. Postdischarge health services, including access to a medical home or a usual source of mental healthcare and measures of medication adherence, were not available in the NRD.

Despite these limitations, the current study underscores the importance of MHCs in hospitalized children upon discharge. As subsequent investigations uncover the key drivers explaining the influence of MHCs on hospital readmission risk, hospitals and their local outpatient and community practices may find it useful to consider MHCs when (1) developing contingency plans and establishing follow-up care at discharge,41 (2) exploring opportunities of care integration between mental and physical health care professionals, and (3) devising strategies to reduce hospital readmissions among populations of children.

CONCLUSIONS

MHCs are prevalent in hospitalized children and are associated with an increased risk of 30-day, unplanned hospital readmission. Future readmission prevention efforts may uncover new ways to improve children’s transitions from hospital to home by investigating strategies to address their MHCs.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Donjo Lau and Troy Richardson for their assistance with the analysis.

Disclosures

Dr. Doupnik was supported by a Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award institutional training grant (T32-HP010026), funded by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Zima was supported by the Behavioral Health Centers of Excellence for California (SB852). Dr. Bardach was supported by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (K23-HD065836). Dr. Berry was supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (R21 HS023092-01). The authors have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose. The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose. Dr. Doupnik led the study design and analysis and drafted the initial manuscript. Mr. Lawlor performed the data analysis. Dr. Hall provided statistical consultation. All authors participated in the design of the study, interpretation of the data, revised the manuscript for key intellectual content, and all authors read and approved the final manuscript.

1. Dougherty D, Schiff J, Mangione-Smith R. The Children’s Health Insurance Program Reauthorization Act quality measures initiatives: moving forward to improve measurement, care, and child and adolescent outcomes. Acad Pediatr. 2011;11(3):S1-S10. PubMed

2. Bardach NS, Vittinghoff E, Asteria-Penaloza R, et al. Measuring Hospital Quality Using Pediatric Readmission and Revisit Rates. Pediatrics. 2013;132(3):429-436. doi:10.1542/peds.2012-3527. PubMed

3. Khan A, Nakamura MM, Zaslavsky AM, et al. Same-Hospital Readmission Rates as a Measure of Pediatric Quality of Care. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169(10):905-912. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.1129. PubMed

4. Fassl BA, Nkoy FL, Stone BL, et al. The Joint Commission Children’s Asthma Care quality measures and asthma readmissions. Pediatrics. 2012;130(3):482-491. doi:10.1542/peds.2011-3318. PubMed

5. Hain PD, Gay JC, Berutti TW, Whitney GM, Wang W, Saville BR. Preventability of Early Readmissions at a Children’s Hospital. Pediatrics. 2013;131(1):e171-e181. doi:10.1542/peds.2012-0820. PubMed

6. Nagasako E, Reidhead B, Waterman B, et al. Adding Socioeconomic Data to Hospital Readmissions Calculations May Produce More Useful Results. Health Aff. 2014;33(5):786-791. PubMed

7. Hu J, Gonsahn MD, Nerenz DR. Socioeconomic Status and Readmissions: Evidence from an Urban Teaching Hospital. Health Aff. 2014;33(5):778-785. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2013.0816. PubMed

8. Sills MR, Hall M, Colvin JD, et al. Association of Social Determinants with Children’s Hospitals’ Preventable Readmissions Performance. JAMA Pediatr. 2016;170(4):350-358. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.4440. PubMed

9. Eselius LL, Cleary PD, Zaslavsky AM, Huskamp HA, Busch SH. Case-Mix Adjustment of Consumer Reports about Managed Behavioral Health Care and Health Plans. Health Serv Res. 2008;43(6):2014-2032. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6773.2008.00894.x. PubMed

10. Doupnik SK, Henry MK, Bae H, et al. Mental Health Conditions and Symptoms in Pediatric Hospitalizations: A Single-Center Point Prevalence Study. Acad Pediatr. 2017;17(2):184-190. PubMed

11. Bardach NS, Coker TR, Zima BT, et al. Common and Costly Hospitalizations for Pediatric Mental Health Disorders. Pediatrics. 2014;133(4):602-609. doi:10.1542/peds.2013-3165. PubMed

12. Doupnik SK, Mitra N, Feudtner C, Marcus SC. The Influence of Comorbid Mood and Anxiety Disorders on Outcomes of Pediatric Patients Hospitalized for Pneumonia. Hosp Pediatr. 2016;6(3):135-142. doi:10.1542/hpeds.2015-0177. PubMed

13. Snell C, Fernandes S, Bujoreanu IS, Garcia G. Depression, illness severity, and healthcare utilization in cystic fibrosis. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2014;49(12):1177-1181. doi:10.1002/ppul.22990. PubMed

14. DiMatteo MR, Lepper HS, Croghan TW. Depression Is a Risk Factor for Noncompliance with Medical Treatment: Meta-analysis of the Effects of Anxiety and Depression on Patient Adherence. Arch Intern Med . 2000;160(14):2101-2107. doi:10.1001/archinte.160.14.2101. PubMed

15. Gray WN, Denson LA, Baldassano RN, Hommel KA. Treatment Adherence in Adolescents with Inflammatory Bowel Disease: The Collective Impact of Barriers to Adherence and Anxiety/Depressive Symptoms. J Pediatr Psychol. 2012;37(3):282-291. doi:10.1093/jpepsy/jsr092. PubMed

16. Mosnaim G, Li H, Martin M, et al. Factors associated with levels of adherence to inhaled corticosteroids in minority adolescents with asthma. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2014;112(2):116-120. doi:10.1016/j.anai.2013.11.021. PubMed

17. Compas BE, Jaser SS, Dunn MJ, Rodriguez EM. Coping with Chronic Illness in Childhood and Adolescence. Ann Rev Clin Psychol. 2012;8(1):455-480. doi:10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032511-143108. PubMed

18. Graue M, Wentzel-Larsen T, Bru E, Hanestad BR, Søvik O. The coping styles of adolescents with type 1 diabetes are associated with degree of metabolic control. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(6):1313-1317. PubMed

19. Jaser SS, White LE. Coping and resilience in adolescents with type 1 diabetes. Child Care Health Dev. 2011;37(3):335-342. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2214.2010.01184.x. PubMed

20. Cancino RS, Culpepper L, Sadikova E, Martin J, Jack BW, Mitchell SE. Dose-response relationship between depressive symptoms and hospital readmission. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(6):358-364. doi:10.1002/jhm.2180. PubMed

21. Pederson JL, Warkentin LM, Majumdar SR, McAlister FA. Depressive symptoms are associated with higher rates of readmission or mortality after medical hospitalization: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(5):373-380. doi:10.1002/jhm.2547. PubMed

22. Chwastiak LA, Davydow DS, McKibbin CL, et al. The Effect of Serious Mental Illness on the Risk of Rehospitalization Among Patients with Diabetes. Psychosomatics. 2014;55(2):134-143. PubMed

23. Daratha KB, Barbosa-Leiker C, H Burley M, et al. Co-occurring mood disorders among hospitalized patients and risk for subsequent medical hospitalization. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2012;34(5):500-505. doi:10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2012.05.001. PubMed

24. Kartha A, Anthony D, Manasseh CS, et al. Depression is a risk factor for rehospitalization in medical inpatients. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;9(4):256-262. PubMed

25. Myrvik MP, Burks LM, Hoffman RG, Dasgupta M, Panepinto JA. Mental health disorders influence admission rates for pain in children with sickle cell disease. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2013;60(7):1211-1214. doi:10.1002/pbc.24394. PubMed

26. Garrison MM, Katon WJ, Richardson LP. The impact of psychiatric comorbidities on readmissions for diabetes in youth. Diabetes Care. 2005;28(9):2150-2154. PubMed

27. Averill R, Goldfield N, Hughes JS, et al. All Patient Refined Diagnosis Related Groups (APR-DRGs) Version 20.0: Methodology Overview. https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/db/nation/nis/APR-DRGsV20MethodologyOverviewandBibliography.pdf. Accessed on November 2, 2016.

28. Berry JG, Toomey SL, Zaslavsky AM, et al. Pediatric readmission prevalence and variability across hospitals. JAMA. 2013;309(4):372-380. PubMed

29. Zima BT, Rodean J, Hall M, Bardach NS, Coker TR, Berry JG. Psychiatric Disorders and Trends in Resource Use in Pediatric Hospitals. Pediatrics. 2016;138(5):e20160909-e20160909. doi:10.1542/peds.2016-0909. PubMed

30. Chronic Condition Indicator (CCI) for ICD-9-CM. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Tools & Software Page. http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/chronic/chronic.jsp. Accessed on October 30, 2015.

31. Feudtner C, Feinstein J, Zhong W, Hall M, Dai D. Pediatric complex chronic conditions classification system version 2: updated for ICD-10 and complex medical technology dependence and transplantation. BMC Pediatr. 2014;14(1):199-205. PubMed

32. Doupnik S, Lawlor J, Zima BT, et al. Mental Health Conditions and Medical and Surgical Hospital Utilization. Pediatrics. 2016;138(6):e20162416. doi:10.1542/peds.2016-2416. PubMed

33. Brown NM, Green JC, Desai MM, Weitzman CC, Rosenthal MS. Need and Unmet Need for Care Coordination Among Children with Mental Health Conditions. Pediatrics. 2014;133(3):e530-e537. doi:10.1542/peds.2013-2590. PubMed

34. Sobolewski B, Richey L, Kowatch RA, Grupp-Phelan J. Mental health follow-up among adolescents with suicidal behaviors after emergency department discharge. Arch Suicide Res. 2013;17(4):323-334. doi:10.1080/13811118.2013.801807. PubMed

35. Hansen LO, Greenwald JL, Budnitz T, et al. Project BOOST: Effectiveness of a multihospital effort to reduce rehospitalization. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(8):421-427. doi:10.1002/jhm.2054. PubMed

36. Di Marco F, Verga M, Santus P, et al. Close correlation between anxiety, depression, and asthma control. Respir Med. 2010;104(1):22-28. doi:10.1016/j.rmed.2009.08.005. PubMed

37. Ghose SS, Williams LS, Swindle RW. Depression and other mental health diagnoses after stroke increase inpatient and outpatient medical utilization three years poststroke. Med Care. 2005;43(12):1259-1264. PubMed

38. Szigethy E, Bujoreanu SI, Youk AO, et al. Randomized efficacy trial of two psychotherapies for depression in youth with inflammatory bowel disease. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2014;53(7):726-735. PubMed

39. Swensen A, Birnbaum HG, Ben Hamadi R, Greenberg P, Cremieux PY, Secnik K. Incidence and costs of accidents among attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder patients. J Adolesc Health. 2004;35(4):346.e1-346.e9. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2003.12.003. PubMed

40. Chan E, Zhan C, Homer CJ. Health Care Use and Costs for Children with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder: National Estimates from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2002;156(5):504-511. doi:10.1001/archpedi.156.5.504. PubMed

41. Berry JG, Blaine K, Rogers J, et al. A Framework of Pediatric Hospital Discharge Care Informed by Legislation, Research, and Practice. JAMA Pediatr. 2014;168(10):955-962. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.891. PubMed

1. Dougherty D, Schiff J, Mangione-Smith R. The Children’s Health Insurance Program Reauthorization Act quality measures initiatives: moving forward to improve measurement, care, and child and adolescent outcomes. Acad Pediatr. 2011;11(3):S1-S10. PubMed

2. Bardach NS, Vittinghoff E, Asteria-Penaloza R, et al. Measuring Hospital Quality Using Pediatric Readmission and Revisit Rates. Pediatrics. 2013;132(3):429-436. doi:10.1542/peds.2012-3527. PubMed

3. Khan A, Nakamura MM, Zaslavsky AM, et al. Same-Hospital Readmission Rates as a Measure of Pediatric Quality of Care. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169(10):905-912. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.1129. PubMed

4. Fassl BA, Nkoy FL, Stone BL, et al. The Joint Commission Children’s Asthma Care quality measures and asthma readmissions. Pediatrics. 2012;130(3):482-491. doi:10.1542/peds.2011-3318. PubMed

5. Hain PD, Gay JC, Berutti TW, Whitney GM, Wang W, Saville BR. Preventability of Early Readmissions at a Children’s Hospital. Pediatrics. 2013;131(1):e171-e181. doi:10.1542/peds.2012-0820. PubMed

6. Nagasako E, Reidhead B, Waterman B, et al. Adding Socioeconomic Data to Hospital Readmissions Calculations May Produce More Useful Results. Health Aff. 2014;33(5):786-791. PubMed

7. Hu J, Gonsahn MD, Nerenz DR. Socioeconomic Status and Readmissions: Evidence from an Urban Teaching Hospital. Health Aff. 2014;33(5):778-785. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2013.0816. PubMed

8. Sills MR, Hall M, Colvin JD, et al. Association of Social Determinants with Children’s Hospitals’ Preventable Readmissions Performance. JAMA Pediatr. 2016;170(4):350-358. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.4440. PubMed

9. Eselius LL, Cleary PD, Zaslavsky AM, Huskamp HA, Busch SH. Case-Mix Adjustment of Consumer Reports about Managed Behavioral Health Care and Health Plans. Health Serv Res. 2008;43(6):2014-2032. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6773.2008.00894.x. PubMed

10. Doupnik SK, Henry MK, Bae H, et al. Mental Health Conditions and Symptoms in Pediatric Hospitalizations: A Single-Center Point Prevalence Study. Acad Pediatr. 2017;17(2):184-190. PubMed

11. Bardach NS, Coker TR, Zima BT, et al. Common and Costly Hospitalizations for Pediatric Mental Health Disorders. Pediatrics. 2014;133(4):602-609. doi:10.1542/peds.2013-3165. PubMed

12. Doupnik SK, Mitra N, Feudtner C, Marcus SC. The Influence of Comorbid Mood and Anxiety Disorders on Outcomes of Pediatric Patients Hospitalized for Pneumonia. Hosp Pediatr. 2016;6(3):135-142. doi:10.1542/hpeds.2015-0177. PubMed

13. Snell C, Fernandes S, Bujoreanu IS, Garcia G. Depression, illness severity, and healthcare utilization in cystic fibrosis. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2014;49(12):1177-1181. doi:10.1002/ppul.22990. PubMed

14. DiMatteo MR, Lepper HS, Croghan TW. Depression Is a Risk Factor for Noncompliance with Medical Treatment: Meta-analysis of the Effects of Anxiety and Depression on Patient Adherence. Arch Intern Med . 2000;160(14):2101-2107. doi:10.1001/archinte.160.14.2101. PubMed