User login

Issues Identified by Postdischarge Contact after Pediatric Hospitalization: A Multisite Study

Many hospitals are considering or currently employing initiatives to contact patients after discharge. Whether conducted via telephone or other means, the purpose of the contact is to help patients adhere to discharge plans, fulfill discharge needs, and alleviate postdischarge issues (PDIs). The effectiveness of hospital-initiated postdischarge phone calls has been studied in adult patients after hospitalization, and though some studies report positive outcomes,1-3 a 2006 Cochrane review found insufficient evidence to recommend for or against the practice.4

Little is known about follow-up contact after hospitalization for children.5-11 Rates of PDI vary substantially across hospitals. For example, one single-center study of postdischarge telephone contact after hospitalization on a general pediatric ward identified PDIs in ~20% of patients.10 Another study identified PDIs in 84% of patients discharged from a pediatric rehabilitation facility.11 Telephone follow-up has been associated with reduced health resource utilization and improved patient satisfaction for children discharged after an elective surgical procedure6 and for children discharged home from the emergency department.7-9

More information is needed on the clinical experiences of postdischarge contact in hospitalized children to improve the understanding of how the contact is made, who makes it, and which patients are most likely to report a PDI. These experiences are crucial to understand given the expense and time commitment involved in postdischarge contact, as many hospitals may not be positioned to contact all discharged patients. Therefore, we conducted a pragmatic, retrospective, naturalistic study of differing approaches to postdischarge contact occurring in multiple hospitals. Our main objective was to describe the prevalence and types of PDIs identified by the different approaches for follow-up contact across 4 children’s hospitals. We also assessed the characteristics of children who have the highest likelihood of having a PDI identified from the contact within each hospital.

METHODS

Study Design, Setting, and Population

Main Outcome Measures

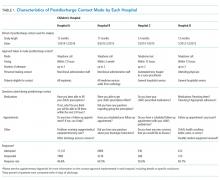

The main outcome measure was identification of a PDI, defined as a medication, appointment, or other discharge-related issue, that was reported and recorded by the child’s caregiver during conversation from the standardized questions that were asked during follow-up contact as part of routine discharge care (Table 1). Medication PDIs included issues filling prescriptions and tolerating medications. Appointment PDIs included not having a follow-up appointment scheduled. Other PDIs included issues with the child’s health condition, discharge instructions, or any other concerns. All PDIs had been recorded prospectively by hospital contact personnel (hospitals A, B, and D) or through an automated texting system into a database (hospital C). Where available, free text comments that were recorded by contact personnel were reviewed by one of the authors (KB) and categorized via an existing framework of PDI designed by Heath et al.10 in order to further understand the problems that were reported.

Patient Characteristics

Patient hospitalization, demographic, and clinical characteristics were obtained from administrative health data at each institution and compared between children with versus without a PDI. Hospitalization characteristics included length of stay, season of admission, and reason for admission. Reason for admission was categorized by using 3M Health’s All Patient Refined Diagnosis Related Groups (APR-DRG) (3M, Maplewood, MN). Demographic characteristics included age at admission in years, insurance type (eg, public, private, and other), and race/ethnicity (Asian/Pacific Islander, Hispanic, non-Hispanic black, non-Hispanic white, and other).

Clinical characteristics included a count of the different classes of medications (eg, antibiotics, antiepileptic medications, digestive motility medications, etc.) administered to the child during admission, the type and number of chronic conditions, and assistance with medical technology (eg, gastrostomy, tracheostomy, etc.). Except for medications, these characteristics were assessed with International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision-Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) diagnosis codes.

We used the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Chronic Condition Indicator classification system, which categorizes over 14,000 ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes into chronic versus nonchronic conditions to identify the presence and number of chronic conditions.12 Children hospitalized with a chronic condition were further classified as having a complex chronic condition (CCC) by using the ICD-9-CM diagnosis classification scheme of Feudtner et al.13 CCCs represent defined diagnosis groupings of conditions expected to last longer than 12 months and involve either multiple organ systems or a single organ system severely enough to require specialty pediatric care and hospitalization.13,14 Children requiring medical technology were identified by using ICD-9-CM codes indicating their use of a medical device to manage and treat a chronic illness (eg, ventricular shunt to treat hydrocephalus) or to maintain basic body functions necessary for sustaining life (eg a tracheostomy tube for breathing).15,16

Statistical Analysis

Given that the primary purpose for this study was to leverage the natural heterogeneity in the approach to follow-up contact across hospitals, we assessed and reported the prevalence and type of PDIs independently for each hospital. Relatedly, we assessed the relationship between patient characteristics and PDI likelihood independently within each hospital as well rather than pool the data and perform a central analysis across hospitals. Of note, APR-DRG and medication class were not assessed for hospital D, as this information was unavailable. We used χ2 tests for univariable analysis and logistic regression with a backwards elimination derivation process (for variables with P ≥ .05) for multivariable analysis; all patient demographic, clinical, and hospitalization characteristics were entered initially into the models. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC), and P < .05 was considered statistically significant. This study was approved by the institutional review board at all hospitals.

RESULTS

Study Population

There were 12,986 (51.4%) of 25,259 patients reached by follow-up contact after discharge across the 4 hospitals. Median age at admission for contacted patients was 4.0 years (interquartile range [IQR] 0-11). Of those contacted, 45.2% were female, 59.9% were non-Hispanic white, 51.0% used Medicaid, and 95.4% were discharged to home. Seventy-one percent had a chronic condition (of any complexity) and 40.8% had a CCC. Eighty percent received a prescribed medication during the hospitalization. Median (IQR) length of stay was 2.0 days (IQR 1-4 days). The top 5 most common reasons for admission were bronchiolitis (6.3%), pneumonia (6.2%), asthma (5.2%), seizure (4.9%), and tonsil and adenoid procedures (4.1%).

PDIs

Characteristics Associated with PDIs

Age

Older age was a consistent characteristic associated with PDIs in 3 hospitals. For example, PDI rates in children 10 to 18 years versus <1 year were 30.8% versus 21.4% (P < .001) in hospital A, 19.4% versus 13.7% (P = .002) in hospital B, and 70.3% versus 62.8% (P < .001) in hospital D. In multivariable analysis, age 10 to 18 years versus <1 year at admission was associated with an increased likelihood of PDI in hospital A (odds ratio [OR] 1.7; 95% CI, 1.4-2.0), hospital B (OR 1.4; 95% CI, 1.1-1.8), and hospital D (OR 1.7; 95% CI, 0.9-3.0) (Table 3 and Figure).

Medications

Length of Stay

Shorter length of stay was associated with PDI in 1 hospital. In hospital A, the PDI rate increased significantly (P < .001) from 19.0% to 33.9% as length of stay decreased from ≥7 days to ≤1 day (Table 3). In multivariable analysis, length of stay to ≤1 day versus ≥7 days was associated with increased likelihood of PDI (OR 2.1; 95% CI, 1.7-2.5) in hospital A (Table 3 and Figure).

CCCs

A neuromuscular CCC was associated with PDI in 2 hospitals. In hospital B, the PDI rate was higher in children with a neuromuscular CCC compared with a malignancy CCC (21.3% vs 11.2%). In hospital D, the PDI rates were higher in children with a neuromuscular CCC compared with a respiratory CCC (68.9% vs 40.6%) (Table 3). In multivariable analysis, children with versus without a neuromuscular CCC had an increased likelihood of PDI (OR 1.3; 95% CI, 1.0-1.7) in hospital B (Table 3 and Figure).

DISCUSSION

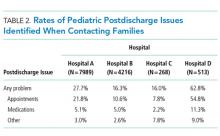

In this retrospective, pragmatic, multicentered study of follow-up contact with a standardized set of questions asked after discharge for hospitalized children, we found that PDIs were identified often, regardless of who made the contact or how the contact was made. The PDI rates varied substantially across hospitals and were likely influenced by the different follow-up approaches that were used. Most PDIs were related to appointments; fewer PDIs were related to medications and other problems. Older age, shorter length of stay, and neuromuscular CCCs were among the identified risk factors for PDIs.

Our assessment of PDIs was, by design, associated with variation in methods and approach for detection across sites. Further investigation is needed to understand how different approaches for follow-up contact after discharge may influence the identification of PDIs. For example, in the current study, the hospital with the highest PDI rate (hospital D) used hospitalists who provided inpatient care for the patient to make follow-up contact. Although not determined from the current study, this approach could have led the hospitalists to ask questions beyond the standardized ones when assessing for PDIs. Perhaps some of the hospitalists had a better understanding of how to probe for PDIs specific to each patient; this understanding may not have been forthcoming for staff in the other hospitals who were unfamiliar with the patients’ hospitalization course and medical history.

Similar to previous studies in adults, our study reported that appointment PDIs in children may be more common than other types of PDIs.17 Appointment PDIs could have been due to scheduling difficulties, inadequate discharge instructions, lack of adherence to recommended follow-up, or other reasons. Further investigation is needed to elucidate these reasons and to determine how to reduce PDIs related to postdischarge appointments. Some children’s hospitals schedule follow-up appointments prior to discharge to mitigate appointment PDIs that might arise.18 However, doing that for every hospitalized child is challenging, especially for very short admissions or for weekend discharges when many outpatient and community practices are not open to schedule appointments. Additional exploration is necessary to assess whether this might help explain why some children in the current study with a short versus long length of stay had a higher likelihood of PDI.

The rate of medication PDIs (5.2%) observed in the current study is lower than the rate that is reported in prior literature. Dudas et al.1 found that medication PDIs occurred in 21% of hospitalized adult patients. One reason for the lower rate of medication PDIs in children may be that they require the use of postdischarge medications less often than adults. Most medication PDIs in the current study involved problems filling a prescription. There was not enough information in the notes taken from the follow-up contact to distinguish the medication PDI etiologies (eg, a prescription was not sent from the hospital team to the pharmacy, prior authorization from an insurance company for a prescription was not obtained, the pharmacy did not stock the medication). To help overcome medication access barriers, some hospitals fill and deliver discharge medications to the patients’ bedside. One study found that children discharged with medication in hand were less likely to have emergency department revisits within 30 days of discharge.19 Further investigation is needed to assess whether initiatives like these help mitigate medication PDIs in children.

Hospitals may benefit from considering how risk factors for PDIs can be used to prioritize which patients receive follow-up contact, especially in hospitals where contact for all hospitalized patients is not feasible. In the current study, there was variation across hospitals in the profile of risk factors that correlated with increased likelihood of PDI. Some of the risk factors are easier to explain than others. For example, as mentioned above, for some hospitalized children, short length of stay might not permit enough time for hospital staff to set up discharge plans that may sufficiently prevent PDIs. Other risk factors, including older age and neuromuscular CCCs, may require additional assessment (eg, through chart review or in-depth patient and provider interviews) to discover the reasons why they were associated with increased likelihood of PDI. There are additional risk factors that might influence the likelihood of PDI that the current study was not positioned to assess, including health literacy, transportation availability, and language spoken.20-23

This study has several other limitations in addition to the ones already mentioned. Some children may have experienced PDIs that were not reported at contact (eg, the respondent was unaware that an issue was present), which may have led to an undercounting of PDIs. Alternatively, some caregivers may have been more likely to respond to the contact if their child was experiencing a PDI, which may have led to overcounting. PDIs of nonrespondents were not measured. PDIs identified by postdischarge outpatient and community providers or by families outside of contact were not measured. The current study was not positioned to assess the severity of the PDIs or what interventions (including additional health services) were needed to address them. Although we assessed medication use during admission, we were unable to assess the number and type of medications that were prescribed for use postdischarge. Information about the number and type of follow-up visits needed for each child was not assessed. Given the variety of approaches for follow-up contact, the findings may generalize best to individual hospitals by using an approach that best matches to one of them. The current study is not positioned to correlate quality of discharge care with the rate of PDI.

Despite these limitations, the findings from the current study reinforce that PDIs identified through follow-up contact in discharged patients appear to be common. Of PDIs identified, appointment problems were more prevalent than medication or other types of problems. Short length of stay, older age, and other patient and/or hospitalization attributes were associated with an increased likelihood of PDI. Hospitals caring for children may find this information useful as they strive to optimize their processes for follow-up contact after discharge. To help further evaluate the value and importance of contacting patients after discharge, additional study of PDI in children is warranted, including (1) actions taken to resolve PDIs, (2) the impact of identifying and addressing PDIs on hospital readmission, and (3) postdischarge experiences and health outcomes of children who responded versus those who did not respond to the follow-up contact. Moreover, future multisite, comparative effectiveness studies of PDI may wish to consider standardization of follow-up contact procedures with controlled manipulation of key processes (eg, contact by administrator vs nurse vs physician) to assess best practices.

Disclosure

Mr. Blaine, Ms. O’Neill, and Drs. Berry, Brittan, Rehm, and Steiner were supported by the Lucile Packard Foundation for Children’s Health. The authors have no financial relationships relative to this article to disclose. The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

1. Dudas V, Bookwalter T, Kerr KM, Pantilat SZ. The impact of follow-up telephone calls to patients after hospitalization. Dis Mon. 2002;48(4):239-248. PubMed

2. Sanchez GM, Douglass MA, Mancuso MA. Revisiting Project Re-Engineered Discharge (RED): The Impact of a Pharmacist Telephone Intervention on Hospital Readmission Rates. Pharmacotherapy. 2015;35(9):805-812. PubMed

3. Jones J, Clark W, Bradford J, Dougherty J. Efficacy of a telephone follow-up system in the emergency department. J Emerg Med. 1988;6(3):249-254. PubMed

4. Mistiaen P, Poot E. Telephone follow-up, initiated by a hospital-based health professional, for postdischarge problems in patients discharged from hospital to home. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006(4):CD004510. PubMed

5. Lushaj EB, Nelson K, Amond K, Kenny E, Badami A, Anagnostopoulos PV. Timely Post-discharge Telephone Follow-Up is a Useful Tool in Identifying Post-discharge Complications Patients After Congenital Heart Surgery. Pediatr Cardiol. 2016;37(6):1106-1110. PubMed

6. McVay MR, Kelley KR, Mathews DL, Jackson RJ, Kokoska ER, Smith SD. Postoperative follow-up: is a phone call enough? J Pediatr Surg. 2008;43(1):83-86. PubMed

7. Chande VT, Exum V. Follow-up phone calls after an emergency department visit. Pediatrics. 1994;93(3):513-514. PubMed

8. Sutton D, Stanley P, Babl FE, Phillips F. Preventing or accelerating emergency care for children with complex healthcare needs. Arch Dis Child. 2008;93(1):17-22. PubMed

9. Patel PB, Vinson DR. Physician e-mail and telephone contact after emergency department visit improves patient satisfaction: a crossover trial. Ann Emerg Med. 2013;61(6):631-637. PubMed

10. Heath J, Dancel R, Stephens JR. Postdischarge phone calls after pediatric hospitalization: an observational study. Hosp Pediatr. 2015;5(5):241-248. PubMed

11. Biffl SE, Biffl WL. Improving transitions of care for complex pediatric trauma patients from inpatient rehabilitation to home: an observational pilot study. Patient Saf Surg. 2015;9:33-37. PubMed

12. AHRQ. Clinical Classifications Software (CCS) for ICD-9-CM. http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/ccs/ccs.jsp. Accessed on January 31,2012.

13. Feudtner C, Christakis DA, Connell FA. Pediatric deaths attributable to complex chronic conditions: a population-based study of Washington State, 1980-1997. Pediatrics. 2000;106(1 Pt 2):205-209. PubMed

14. Berry JG, Hall DE, Kuo DZ, et al. Hospital utilization and characteristics of patients experiencing recurrent readmissions within children’s hospitals. JAMA. 2011;305(7):682-690. PubMed

15. Palfrey JS, Walker DK, Haynie M, et al. Technology’s children: report of a statewide census of children dependent on medical supports. Pediatrics. 1991;87(5):611-618. PubMed

16. Feudtner C, Villareale NL, Morray B, Sharp V, Hays RM, Neff JM. Technology-dependency among patients discharged from a children’s hospital: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Pediatr. 2005;5(1):8-15. PubMed

17. Arora VM, Prochaska ML, Farnan JM, et al. Problems after discharge and understanding of communication with their primary care physicians among hospitalized seniors: a mixed methods study. J Hosp Med. 2010;5(7):385-391. PubMed

18. Brittan M, Tyler A, Martin S, et al. A Discharge Planning Template for the Electronic Medical Record Improves Scheduling of Neurology Follow-up for Comanaged Seizure Patients. Hosp Pediatr. 2014;4(6):366-371. PubMed

19. Hatoun J, Bair-Merritt M, Cabral H, Moses J. Increasing Medication Possession at Discharge for Patients With Asthma: The Meds-in-Hand Project. Pediatrics. 2016;137(3):e20150461. doi:10.1542/peds.2015-0461. PubMed

20. Berry JG, Goldmann DA, Mandl KD, et al. Health information management and perceptions of the quality of care for children with tracheotomy: a qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2011;11:117-125. PubMed

21. Berry JG, Ziniel SI, Freeman L, et al. Hospital readmission and parent perceptions of their child’s hospital discharge. Int J Qual Health Care. 2013;25(5):573-581. PubMed

22. Carusone SC, O’Leary B, McWatt S, Stewart A, Craig S, Brennan DJ. The Lived Experience of the Hospital Discharge “Plan”: A Longitudinal Qualitative Study of Complex Patients. J Hosp Med. 2017;12(1):5-10. PubMed

23. Leyenaar JK, O’Brien ER, Leslie LK, Lindenauer PK, Mangione-Smith RM. Families’ Priorities Regarding Hospital-to-Home Transitions for Children With Medical Complexity. Pediatrics. 2017;139(1):e20161581. doi:10.1542/peds.2016-1581. PubMed

Many hospitals are considering or currently employing initiatives to contact patients after discharge. Whether conducted via telephone or other means, the purpose of the contact is to help patients adhere to discharge plans, fulfill discharge needs, and alleviate postdischarge issues (PDIs). The effectiveness of hospital-initiated postdischarge phone calls has been studied in adult patients after hospitalization, and though some studies report positive outcomes,1-3 a 2006 Cochrane review found insufficient evidence to recommend for or against the practice.4

Little is known about follow-up contact after hospitalization for children.5-11 Rates of PDI vary substantially across hospitals. For example, one single-center study of postdischarge telephone contact after hospitalization on a general pediatric ward identified PDIs in ~20% of patients.10 Another study identified PDIs in 84% of patients discharged from a pediatric rehabilitation facility.11 Telephone follow-up has been associated with reduced health resource utilization and improved patient satisfaction for children discharged after an elective surgical procedure6 and for children discharged home from the emergency department.7-9

More information is needed on the clinical experiences of postdischarge contact in hospitalized children to improve the understanding of how the contact is made, who makes it, and which patients are most likely to report a PDI. These experiences are crucial to understand given the expense and time commitment involved in postdischarge contact, as many hospitals may not be positioned to contact all discharged patients. Therefore, we conducted a pragmatic, retrospective, naturalistic study of differing approaches to postdischarge contact occurring in multiple hospitals. Our main objective was to describe the prevalence and types of PDIs identified by the different approaches for follow-up contact across 4 children’s hospitals. We also assessed the characteristics of children who have the highest likelihood of having a PDI identified from the contact within each hospital.

METHODS

Study Design, Setting, and Population

Main Outcome Measures

The main outcome measure was identification of a PDI, defined as a medication, appointment, or other discharge-related issue, that was reported and recorded by the child’s caregiver during conversation from the standardized questions that were asked during follow-up contact as part of routine discharge care (Table 1). Medication PDIs included issues filling prescriptions and tolerating medications. Appointment PDIs included not having a follow-up appointment scheduled. Other PDIs included issues with the child’s health condition, discharge instructions, or any other concerns. All PDIs had been recorded prospectively by hospital contact personnel (hospitals A, B, and D) or through an automated texting system into a database (hospital C). Where available, free text comments that were recorded by contact personnel were reviewed by one of the authors (KB) and categorized via an existing framework of PDI designed by Heath et al.10 in order to further understand the problems that were reported.

Patient Characteristics

Patient hospitalization, demographic, and clinical characteristics were obtained from administrative health data at each institution and compared between children with versus without a PDI. Hospitalization characteristics included length of stay, season of admission, and reason for admission. Reason for admission was categorized by using 3M Health’s All Patient Refined Diagnosis Related Groups (APR-DRG) (3M, Maplewood, MN). Demographic characteristics included age at admission in years, insurance type (eg, public, private, and other), and race/ethnicity (Asian/Pacific Islander, Hispanic, non-Hispanic black, non-Hispanic white, and other).

Clinical characteristics included a count of the different classes of medications (eg, antibiotics, antiepileptic medications, digestive motility medications, etc.) administered to the child during admission, the type and number of chronic conditions, and assistance with medical technology (eg, gastrostomy, tracheostomy, etc.). Except for medications, these characteristics were assessed with International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision-Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) diagnosis codes.

We used the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Chronic Condition Indicator classification system, which categorizes over 14,000 ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes into chronic versus nonchronic conditions to identify the presence and number of chronic conditions.12 Children hospitalized with a chronic condition were further classified as having a complex chronic condition (CCC) by using the ICD-9-CM diagnosis classification scheme of Feudtner et al.13 CCCs represent defined diagnosis groupings of conditions expected to last longer than 12 months and involve either multiple organ systems or a single organ system severely enough to require specialty pediatric care and hospitalization.13,14 Children requiring medical technology were identified by using ICD-9-CM codes indicating their use of a medical device to manage and treat a chronic illness (eg, ventricular shunt to treat hydrocephalus) or to maintain basic body functions necessary for sustaining life (eg a tracheostomy tube for breathing).15,16

Statistical Analysis

Given that the primary purpose for this study was to leverage the natural heterogeneity in the approach to follow-up contact across hospitals, we assessed and reported the prevalence and type of PDIs independently for each hospital. Relatedly, we assessed the relationship between patient characteristics and PDI likelihood independently within each hospital as well rather than pool the data and perform a central analysis across hospitals. Of note, APR-DRG and medication class were not assessed for hospital D, as this information was unavailable. We used χ2 tests for univariable analysis and logistic regression with a backwards elimination derivation process (for variables with P ≥ .05) for multivariable analysis; all patient demographic, clinical, and hospitalization characteristics were entered initially into the models. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC), and P < .05 was considered statistically significant. This study was approved by the institutional review board at all hospitals.

RESULTS

Study Population

There were 12,986 (51.4%) of 25,259 patients reached by follow-up contact after discharge across the 4 hospitals. Median age at admission for contacted patients was 4.0 years (interquartile range [IQR] 0-11). Of those contacted, 45.2% were female, 59.9% were non-Hispanic white, 51.0% used Medicaid, and 95.4% were discharged to home. Seventy-one percent had a chronic condition (of any complexity) and 40.8% had a CCC. Eighty percent received a prescribed medication during the hospitalization. Median (IQR) length of stay was 2.0 days (IQR 1-4 days). The top 5 most common reasons for admission were bronchiolitis (6.3%), pneumonia (6.2%), asthma (5.2%), seizure (4.9%), and tonsil and adenoid procedures (4.1%).

PDIs

Characteristics Associated with PDIs

Age

Older age was a consistent characteristic associated with PDIs in 3 hospitals. For example, PDI rates in children 10 to 18 years versus <1 year were 30.8% versus 21.4% (P < .001) in hospital A, 19.4% versus 13.7% (P = .002) in hospital B, and 70.3% versus 62.8% (P < .001) in hospital D. In multivariable analysis, age 10 to 18 years versus <1 year at admission was associated with an increased likelihood of PDI in hospital A (odds ratio [OR] 1.7; 95% CI, 1.4-2.0), hospital B (OR 1.4; 95% CI, 1.1-1.8), and hospital D (OR 1.7; 95% CI, 0.9-3.0) (Table 3 and Figure).

Medications

Length of Stay

Shorter length of stay was associated with PDI in 1 hospital. In hospital A, the PDI rate increased significantly (P < .001) from 19.0% to 33.9% as length of stay decreased from ≥7 days to ≤1 day (Table 3). In multivariable analysis, length of stay to ≤1 day versus ≥7 days was associated with increased likelihood of PDI (OR 2.1; 95% CI, 1.7-2.5) in hospital A (Table 3 and Figure).

CCCs

A neuromuscular CCC was associated with PDI in 2 hospitals. In hospital B, the PDI rate was higher in children with a neuromuscular CCC compared with a malignancy CCC (21.3% vs 11.2%). In hospital D, the PDI rates were higher in children with a neuromuscular CCC compared with a respiratory CCC (68.9% vs 40.6%) (Table 3). In multivariable analysis, children with versus without a neuromuscular CCC had an increased likelihood of PDI (OR 1.3; 95% CI, 1.0-1.7) in hospital B (Table 3 and Figure).

DISCUSSION

In this retrospective, pragmatic, multicentered study of follow-up contact with a standardized set of questions asked after discharge for hospitalized children, we found that PDIs were identified often, regardless of who made the contact or how the contact was made. The PDI rates varied substantially across hospitals and were likely influenced by the different follow-up approaches that were used. Most PDIs were related to appointments; fewer PDIs were related to medications and other problems. Older age, shorter length of stay, and neuromuscular CCCs were among the identified risk factors for PDIs.

Our assessment of PDIs was, by design, associated with variation in methods and approach for detection across sites. Further investigation is needed to understand how different approaches for follow-up contact after discharge may influence the identification of PDIs. For example, in the current study, the hospital with the highest PDI rate (hospital D) used hospitalists who provided inpatient care for the patient to make follow-up contact. Although not determined from the current study, this approach could have led the hospitalists to ask questions beyond the standardized ones when assessing for PDIs. Perhaps some of the hospitalists had a better understanding of how to probe for PDIs specific to each patient; this understanding may not have been forthcoming for staff in the other hospitals who were unfamiliar with the patients’ hospitalization course and medical history.

Similar to previous studies in adults, our study reported that appointment PDIs in children may be more common than other types of PDIs.17 Appointment PDIs could have been due to scheduling difficulties, inadequate discharge instructions, lack of adherence to recommended follow-up, or other reasons. Further investigation is needed to elucidate these reasons and to determine how to reduce PDIs related to postdischarge appointments. Some children’s hospitals schedule follow-up appointments prior to discharge to mitigate appointment PDIs that might arise.18 However, doing that for every hospitalized child is challenging, especially for very short admissions or for weekend discharges when many outpatient and community practices are not open to schedule appointments. Additional exploration is necessary to assess whether this might help explain why some children in the current study with a short versus long length of stay had a higher likelihood of PDI.

The rate of medication PDIs (5.2%) observed in the current study is lower than the rate that is reported in prior literature. Dudas et al.1 found that medication PDIs occurred in 21% of hospitalized adult patients. One reason for the lower rate of medication PDIs in children may be that they require the use of postdischarge medications less often than adults. Most medication PDIs in the current study involved problems filling a prescription. There was not enough information in the notes taken from the follow-up contact to distinguish the medication PDI etiologies (eg, a prescription was not sent from the hospital team to the pharmacy, prior authorization from an insurance company for a prescription was not obtained, the pharmacy did not stock the medication). To help overcome medication access barriers, some hospitals fill and deliver discharge medications to the patients’ bedside. One study found that children discharged with medication in hand were less likely to have emergency department revisits within 30 days of discharge.19 Further investigation is needed to assess whether initiatives like these help mitigate medication PDIs in children.

Hospitals may benefit from considering how risk factors for PDIs can be used to prioritize which patients receive follow-up contact, especially in hospitals where contact for all hospitalized patients is not feasible. In the current study, there was variation across hospitals in the profile of risk factors that correlated with increased likelihood of PDI. Some of the risk factors are easier to explain than others. For example, as mentioned above, for some hospitalized children, short length of stay might not permit enough time for hospital staff to set up discharge plans that may sufficiently prevent PDIs. Other risk factors, including older age and neuromuscular CCCs, may require additional assessment (eg, through chart review or in-depth patient and provider interviews) to discover the reasons why they were associated with increased likelihood of PDI. There are additional risk factors that might influence the likelihood of PDI that the current study was not positioned to assess, including health literacy, transportation availability, and language spoken.20-23

This study has several other limitations in addition to the ones already mentioned. Some children may have experienced PDIs that were not reported at contact (eg, the respondent was unaware that an issue was present), which may have led to an undercounting of PDIs. Alternatively, some caregivers may have been more likely to respond to the contact if their child was experiencing a PDI, which may have led to overcounting. PDIs of nonrespondents were not measured. PDIs identified by postdischarge outpatient and community providers or by families outside of contact were not measured. The current study was not positioned to assess the severity of the PDIs or what interventions (including additional health services) were needed to address them. Although we assessed medication use during admission, we were unable to assess the number and type of medications that were prescribed for use postdischarge. Information about the number and type of follow-up visits needed for each child was not assessed. Given the variety of approaches for follow-up contact, the findings may generalize best to individual hospitals by using an approach that best matches to one of them. The current study is not positioned to correlate quality of discharge care with the rate of PDI.

Despite these limitations, the findings from the current study reinforce that PDIs identified through follow-up contact in discharged patients appear to be common. Of PDIs identified, appointment problems were more prevalent than medication or other types of problems. Short length of stay, older age, and other patient and/or hospitalization attributes were associated with an increased likelihood of PDI. Hospitals caring for children may find this information useful as they strive to optimize their processes for follow-up contact after discharge. To help further evaluate the value and importance of contacting patients after discharge, additional study of PDI in children is warranted, including (1) actions taken to resolve PDIs, (2) the impact of identifying and addressing PDIs on hospital readmission, and (3) postdischarge experiences and health outcomes of children who responded versus those who did not respond to the follow-up contact. Moreover, future multisite, comparative effectiveness studies of PDI may wish to consider standardization of follow-up contact procedures with controlled manipulation of key processes (eg, contact by administrator vs nurse vs physician) to assess best practices.

Disclosure

Mr. Blaine, Ms. O’Neill, and Drs. Berry, Brittan, Rehm, and Steiner were supported by the Lucile Packard Foundation for Children’s Health. The authors have no financial relationships relative to this article to disclose. The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Many hospitals are considering or currently employing initiatives to contact patients after discharge. Whether conducted via telephone or other means, the purpose of the contact is to help patients adhere to discharge plans, fulfill discharge needs, and alleviate postdischarge issues (PDIs). The effectiveness of hospital-initiated postdischarge phone calls has been studied in adult patients after hospitalization, and though some studies report positive outcomes,1-3 a 2006 Cochrane review found insufficient evidence to recommend for or against the practice.4

Little is known about follow-up contact after hospitalization for children.5-11 Rates of PDI vary substantially across hospitals. For example, one single-center study of postdischarge telephone contact after hospitalization on a general pediatric ward identified PDIs in ~20% of patients.10 Another study identified PDIs in 84% of patients discharged from a pediatric rehabilitation facility.11 Telephone follow-up has been associated with reduced health resource utilization and improved patient satisfaction for children discharged after an elective surgical procedure6 and for children discharged home from the emergency department.7-9

More information is needed on the clinical experiences of postdischarge contact in hospitalized children to improve the understanding of how the contact is made, who makes it, and which patients are most likely to report a PDI. These experiences are crucial to understand given the expense and time commitment involved in postdischarge contact, as many hospitals may not be positioned to contact all discharged patients. Therefore, we conducted a pragmatic, retrospective, naturalistic study of differing approaches to postdischarge contact occurring in multiple hospitals. Our main objective was to describe the prevalence and types of PDIs identified by the different approaches for follow-up contact across 4 children’s hospitals. We also assessed the characteristics of children who have the highest likelihood of having a PDI identified from the contact within each hospital.

METHODS

Study Design, Setting, and Population

Main Outcome Measures

The main outcome measure was identification of a PDI, defined as a medication, appointment, or other discharge-related issue, that was reported and recorded by the child’s caregiver during conversation from the standardized questions that were asked during follow-up contact as part of routine discharge care (Table 1). Medication PDIs included issues filling prescriptions and tolerating medications. Appointment PDIs included not having a follow-up appointment scheduled. Other PDIs included issues with the child’s health condition, discharge instructions, or any other concerns. All PDIs had been recorded prospectively by hospital contact personnel (hospitals A, B, and D) or through an automated texting system into a database (hospital C). Where available, free text comments that were recorded by contact personnel were reviewed by one of the authors (KB) and categorized via an existing framework of PDI designed by Heath et al.10 in order to further understand the problems that were reported.

Patient Characteristics

Patient hospitalization, demographic, and clinical characteristics were obtained from administrative health data at each institution and compared between children with versus without a PDI. Hospitalization characteristics included length of stay, season of admission, and reason for admission. Reason for admission was categorized by using 3M Health’s All Patient Refined Diagnosis Related Groups (APR-DRG) (3M, Maplewood, MN). Demographic characteristics included age at admission in years, insurance type (eg, public, private, and other), and race/ethnicity (Asian/Pacific Islander, Hispanic, non-Hispanic black, non-Hispanic white, and other).

Clinical characteristics included a count of the different classes of medications (eg, antibiotics, antiepileptic medications, digestive motility medications, etc.) administered to the child during admission, the type and number of chronic conditions, and assistance with medical technology (eg, gastrostomy, tracheostomy, etc.). Except for medications, these characteristics were assessed with International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision-Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) diagnosis codes.

We used the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Chronic Condition Indicator classification system, which categorizes over 14,000 ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes into chronic versus nonchronic conditions to identify the presence and number of chronic conditions.12 Children hospitalized with a chronic condition were further classified as having a complex chronic condition (CCC) by using the ICD-9-CM diagnosis classification scheme of Feudtner et al.13 CCCs represent defined diagnosis groupings of conditions expected to last longer than 12 months and involve either multiple organ systems or a single organ system severely enough to require specialty pediatric care and hospitalization.13,14 Children requiring medical technology were identified by using ICD-9-CM codes indicating their use of a medical device to manage and treat a chronic illness (eg, ventricular shunt to treat hydrocephalus) or to maintain basic body functions necessary for sustaining life (eg a tracheostomy tube for breathing).15,16

Statistical Analysis

Given that the primary purpose for this study was to leverage the natural heterogeneity in the approach to follow-up contact across hospitals, we assessed and reported the prevalence and type of PDIs independently for each hospital. Relatedly, we assessed the relationship between patient characteristics and PDI likelihood independently within each hospital as well rather than pool the data and perform a central analysis across hospitals. Of note, APR-DRG and medication class were not assessed for hospital D, as this information was unavailable. We used χ2 tests for univariable analysis and logistic regression with a backwards elimination derivation process (for variables with P ≥ .05) for multivariable analysis; all patient demographic, clinical, and hospitalization characteristics were entered initially into the models. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC), and P < .05 was considered statistically significant. This study was approved by the institutional review board at all hospitals.

RESULTS

Study Population

There were 12,986 (51.4%) of 25,259 patients reached by follow-up contact after discharge across the 4 hospitals. Median age at admission for contacted patients was 4.0 years (interquartile range [IQR] 0-11). Of those contacted, 45.2% were female, 59.9% were non-Hispanic white, 51.0% used Medicaid, and 95.4% were discharged to home. Seventy-one percent had a chronic condition (of any complexity) and 40.8% had a CCC. Eighty percent received a prescribed medication during the hospitalization. Median (IQR) length of stay was 2.0 days (IQR 1-4 days). The top 5 most common reasons for admission were bronchiolitis (6.3%), pneumonia (6.2%), asthma (5.2%), seizure (4.9%), and tonsil and adenoid procedures (4.1%).

PDIs

Characteristics Associated with PDIs

Age

Older age was a consistent characteristic associated with PDIs in 3 hospitals. For example, PDI rates in children 10 to 18 years versus <1 year were 30.8% versus 21.4% (P < .001) in hospital A, 19.4% versus 13.7% (P = .002) in hospital B, and 70.3% versus 62.8% (P < .001) in hospital D. In multivariable analysis, age 10 to 18 years versus <1 year at admission was associated with an increased likelihood of PDI in hospital A (odds ratio [OR] 1.7; 95% CI, 1.4-2.0), hospital B (OR 1.4; 95% CI, 1.1-1.8), and hospital D (OR 1.7; 95% CI, 0.9-3.0) (Table 3 and Figure).

Medications

Length of Stay

Shorter length of stay was associated with PDI in 1 hospital. In hospital A, the PDI rate increased significantly (P < .001) from 19.0% to 33.9% as length of stay decreased from ≥7 days to ≤1 day (Table 3). In multivariable analysis, length of stay to ≤1 day versus ≥7 days was associated with increased likelihood of PDI (OR 2.1; 95% CI, 1.7-2.5) in hospital A (Table 3 and Figure).

CCCs

A neuromuscular CCC was associated with PDI in 2 hospitals. In hospital B, the PDI rate was higher in children with a neuromuscular CCC compared with a malignancy CCC (21.3% vs 11.2%). In hospital D, the PDI rates were higher in children with a neuromuscular CCC compared with a respiratory CCC (68.9% vs 40.6%) (Table 3). In multivariable analysis, children with versus without a neuromuscular CCC had an increased likelihood of PDI (OR 1.3; 95% CI, 1.0-1.7) in hospital B (Table 3 and Figure).

DISCUSSION

In this retrospective, pragmatic, multicentered study of follow-up contact with a standardized set of questions asked after discharge for hospitalized children, we found that PDIs were identified often, regardless of who made the contact or how the contact was made. The PDI rates varied substantially across hospitals and were likely influenced by the different follow-up approaches that were used. Most PDIs were related to appointments; fewer PDIs were related to medications and other problems. Older age, shorter length of stay, and neuromuscular CCCs were among the identified risk factors for PDIs.

Our assessment of PDIs was, by design, associated with variation in methods and approach for detection across sites. Further investigation is needed to understand how different approaches for follow-up contact after discharge may influence the identification of PDIs. For example, in the current study, the hospital with the highest PDI rate (hospital D) used hospitalists who provided inpatient care for the patient to make follow-up contact. Although not determined from the current study, this approach could have led the hospitalists to ask questions beyond the standardized ones when assessing for PDIs. Perhaps some of the hospitalists had a better understanding of how to probe for PDIs specific to each patient; this understanding may not have been forthcoming for staff in the other hospitals who were unfamiliar with the patients’ hospitalization course and medical history.

Similar to previous studies in adults, our study reported that appointment PDIs in children may be more common than other types of PDIs.17 Appointment PDIs could have been due to scheduling difficulties, inadequate discharge instructions, lack of adherence to recommended follow-up, or other reasons. Further investigation is needed to elucidate these reasons and to determine how to reduce PDIs related to postdischarge appointments. Some children’s hospitals schedule follow-up appointments prior to discharge to mitigate appointment PDIs that might arise.18 However, doing that for every hospitalized child is challenging, especially for very short admissions or for weekend discharges when many outpatient and community practices are not open to schedule appointments. Additional exploration is necessary to assess whether this might help explain why some children in the current study with a short versus long length of stay had a higher likelihood of PDI.

The rate of medication PDIs (5.2%) observed in the current study is lower than the rate that is reported in prior literature. Dudas et al.1 found that medication PDIs occurred in 21% of hospitalized adult patients. One reason for the lower rate of medication PDIs in children may be that they require the use of postdischarge medications less often than adults. Most medication PDIs in the current study involved problems filling a prescription. There was not enough information in the notes taken from the follow-up contact to distinguish the medication PDI etiologies (eg, a prescription was not sent from the hospital team to the pharmacy, prior authorization from an insurance company for a prescription was not obtained, the pharmacy did not stock the medication). To help overcome medication access barriers, some hospitals fill and deliver discharge medications to the patients’ bedside. One study found that children discharged with medication in hand were less likely to have emergency department revisits within 30 days of discharge.19 Further investigation is needed to assess whether initiatives like these help mitigate medication PDIs in children.

Hospitals may benefit from considering how risk factors for PDIs can be used to prioritize which patients receive follow-up contact, especially in hospitals where contact for all hospitalized patients is not feasible. In the current study, there was variation across hospitals in the profile of risk factors that correlated with increased likelihood of PDI. Some of the risk factors are easier to explain than others. For example, as mentioned above, for some hospitalized children, short length of stay might not permit enough time for hospital staff to set up discharge plans that may sufficiently prevent PDIs. Other risk factors, including older age and neuromuscular CCCs, may require additional assessment (eg, through chart review or in-depth patient and provider interviews) to discover the reasons why they were associated with increased likelihood of PDI. There are additional risk factors that might influence the likelihood of PDI that the current study was not positioned to assess, including health literacy, transportation availability, and language spoken.20-23

This study has several other limitations in addition to the ones already mentioned. Some children may have experienced PDIs that were not reported at contact (eg, the respondent was unaware that an issue was present), which may have led to an undercounting of PDIs. Alternatively, some caregivers may have been more likely to respond to the contact if their child was experiencing a PDI, which may have led to overcounting. PDIs of nonrespondents were not measured. PDIs identified by postdischarge outpatient and community providers or by families outside of contact were not measured. The current study was not positioned to assess the severity of the PDIs or what interventions (including additional health services) were needed to address them. Although we assessed medication use during admission, we were unable to assess the number and type of medications that were prescribed for use postdischarge. Information about the number and type of follow-up visits needed for each child was not assessed. Given the variety of approaches for follow-up contact, the findings may generalize best to individual hospitals by using an approach that best matches to one of them. The current study is not positioned to correlate quality of discharge care with the rate of PDI.

Despite these limitations, the findings from the current study reinforce that PDIs identified through follow-up contact in discharged patients appear to be common. Of PDIs identified, appointment problems were more prevalent than medication or other types of problems. Short length of stay, older age, and other patient and/or hospitalization attributes were associated with an increased likelihood of PDI. Hospitals caring for children may find this information useful as they strive to optimize their processes for follow-up contact after discharge. To help further evaluate the value and importance of contacting patients after discharge, additional study of PDI in children is warranted, including (1) actions taken to resolve PDIs, (2) the impact of identifying and addressing PDIs on hospital readmission, and (3) postdischarge experiences and health outcomes of children who responded versus those who did not respond to the follow-up contact. Moreover, future multisite, comparative effectiveness studies of PDI may wish to consider standardization of follow-up contact procedures with controlled manipulation of key processes (eg, contact by administrator vs nurse vs physician) to assess best practices.

Disclosure

Mr. Blaine, Ms. O’Neill, and Drs. Berry, Brittan, Rehm, and Steiner were supported by the Lucile Packard Foundation for Children’s Health. The authors have no financial relationships relative to this article to disclose. The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

1. Dudas V, Bookwalter T, Kerr KM, Pantilat SZ. The impact of follow-up telephone calls to patients after hospitalization. Dis Mon. 2002;48(4):239-248. PubMed

2. Sanchez GM, Douglass MA, Mancuso MA. Revisiting Project Re-Engineered Discharge (RED): The Impact of a Pharmacist Telephone Intervention on Hospital Readmission Rates. Pharmacotherapy. 2015;35(9):805-812. PubMed

3. Jones J, Clark W, Bradford J, Dougherty J. Efficacy of a telephone follow-up system in the emergency department. J Emerg Med. 1988;6(3):249-254. PubMed

4. Mistiaen P, Poot E. Telephone follow-up, initiated by a hospital-based health professional, for postdischarge problems in patients discharged from hospital to home. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006(4):CD004510. PubMed

5. Lushaj EB, Nelson K, Amond K, Kenny E, Badami A, Anagnostopoulos PV. Timely Post-discharge Telephone Follow-Up is a Useful Tool in Identifying Post-discharge Complications Patients After Congenital Heart Surgery. Pediatr Cardiol. 2016;37(6):1106-1110. PubMed

6. McVay MR, Kelley KR, Mathews DL, Jackson RJ, Kokoska ER, Smith SD. Postoperative follow-up: is a phone call enough? J Pediatr Surg. 2008;43(1):83-86. PubMed

7. Chande VT, Exum V. Follow-up phone calls after an emergency department visit. Pediatrics. 1994;93(3):513-514. PubMed

8. Sutton D, Stanley P, Babl FE, Phillips F. Preventing or accelerating emergency care for children with complex healthcare needs. Arch Dis Child. 2008;93(1):17-22. PubMed

9. Patel PB, Vinson DR. Physician e-mail and telephone contact after emergency department visit improves patient satisfaction: a crossover trial. Ann Emerg Med. 2013;61(6):631-637. PubMed

10. Heath J, Dancel R, Stephens JR. Postdischarge phone calls after pediatric hospitalization: an observational study. Hosp Pediatr. 2015;5(5):241-248. PubMed

11. Biffl SE, Biffl WL. Improving transitions of care for complex pediatric trauma patients from inpatient rehabilitation to home: an observational pilot study. Patient Saf Surg. 2015;9:33-37. PubMed

12. AHRQ. Clinical Classifications Software (CCS) for ICD-9-CM. http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/ccs/ccs.jsp. Accessed on January 31,2012.

13. Feudtner C, Christakis DA, Connell FA. Pediatric deaths attributable to complex chronic conditions: a population-based study of Washington State, 1980-1997. Pediatrics. 2000;106(1 Pt 2):205-209. PubMed

14. Berry JG, Hall DE, Kuo DZ, et al. Hospital utilization and characteristics of patients experiencing recurrent readmissions within children’s hospitals. JAMA. 2011;305(7):682-690. PubMed

15. Palfrey JS, Walker DK, Haynie M, et al. Technology’s children: report of a statewide census of children dependent on medical supports. Pediatrics. 1991;87(5):611-618. PubMed

16. Feudtner C, Villareale NL, Morray B, Sharp V, Hays RM, Neff JM. Technology-dependency among patients discharged from a children’s hospital: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Pediatr. 2005;5(1):8-15. PubMed

17. Arora VM, Prochaska ML, Farnan JM, et al. Problems after discharge and understanding of communication with their primary care physicians among hospitalized seniors: a mixed methods study. J Hosp Med. 2010;5(7):385-391. PubMed

18. Brittan M, Tyler A, Martin S, et al. A Discharge Planning Template for the Electronic Medical Record Improves Scheduling of Neurology Follow-up for Comanaged Seizure Patients. Hosp Pediatr. 2014;4(6):366-371. PubMed

19. Hatoun J, Bair-Merritt M, Cabral H, Moses J. Increasing Medication Possession at Discharge for Patients With Asthma: The Meds-in-Hand Project. Pediatrics. 2016;137(3):e20150461. doi:10.1542/peds.2015-0461. PubMed

20. Berry JG, Goldmann DA, Mandl KD, et al. Health information management and perceptions of the quality of care for children with tracheotomy: a qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2011;11:117-125. PubMed

21. Berry JG, Ziniel SI, Freeman L, et al. Hospital readmission and parent perceptions of their child’s hospital discharge. Int J Qual Health Care. 2013;25(5):573-581. PubMed

22. Carusone SC, O’Leary B, McWatt S, Stewart A, Craig S, Brennan DJ. The Lived Experience of the Hospital Discharge “Plan”: A Longitudinal Qualitative Study of Complex Patients. J Hosp Med. 2017;12(1):5-10. PubMed

23. Leyenaar JK, O’Brien ER, Leslie LK, Lindenauer PK, Mangione-Smith RM. Families’ Priorities Regarding Hospital-to-Home Transitions for Children With Medical Complexity. Pediatrics. 2017;139(1):e20161581. doi:10.1542/peds.2016-1581. PubMed

1. Dudas V, Bookwalter T, Kerr KM, Pantilat SZ. The impact of follow-up telephone calls to patients after hospitalization. Dis Mon. 2002;48(4):239-248. PubMed

2. Sanchez GM, Douglass MA, Mancuso MA. Revisiting Project Re-Engineered Discharge (RED): The Impact of a Pharmacist Telephone Intervention on Hospital Readmission Rates. Pharmacotherapy. 2015;35(9):805-812. PubMed

3. Jones J, Clark W, Bradford J, Dougherty J. Efficacy of a telephone follow-up system in the emergency department. J Emerg Med. 1988;6(3):249-254. PubMed

4. Mistiaen P, Poot E. Telephone follow-up, initiated by a hospital-based health professional, for postdischarge problems in patients discharged from hospital to home. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006(4):CD004510. PubMed

5. Lushaj EB, Nelson K, Amond K, Kenny E, Badami A, Anagnostopoulos PV. Timely Post-discharge Telephone Follow-Up is a Useful Tool in Identifying Post-discharge Complications Patients After Congenital Heart Surgery. Pediatr Cardiol. 2016;37(6):1106-1110. PubMed

6. McVay MR, Kelley KR, Mathews DL, Jackson RJ, Kokoska ER, Smith SD. Postoperative follow-up: is a phone call enough? J Pediatr Surg. 2008;43(1):83-86. PubMed

7. Chande VT, Exum V. Follow-up phone calls after an emergency department visit. Pediatrics. 1994;93(3):513-514. PubMed

8. Sutton D, Stanley P, Babl FE, Phillips F. Preventing or accelerating emergency care for children with complex healthcare needs. Arch Dis Child. 2008;93(1):17-22. PubMed

9. Patel PB, Vinson DR. Physician e-mail and telephone contact after emergency department visit improves patient satisfaction: a crossover trial. Ann Emerg Med. 2013;61(6):631-637. PubMed

10. Heath J, Dancel R, Stephens JR. Postdischarge phone calls after pediatric hospitalization: an observational study. Hosp Pediatr. 2015;5(5):241-248. PubMed

11. Biffl SE, Biffl WL. Improving transitions of care for complex pediatric trauma patients from inpatient rehabilitation to home: an observational pilot study. Patient Saf Surg. 2015;9:33-37. PubMed

12. AHRQ. Clinical Classifications Software (CCS) for ICD-9-CM. http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/ccs/ccs.jsp. Accessed on January 31,2012.

13. Feudtner C, Christakis DA, Connell FA. Pediatric deaths attributable to complex chronic conditions: a population-based study of Washington State, 1980-1997. Pediatrics. 2000;106(1 Pt 2):205-209. PubMed

14. Berry JG, Hall DE, Kuo DZ, et al. Hospital utilization and characteristics of patients experiencing recurrent readmissions within children’s hospitals. JAMA. 2011;305(7):682-690. PubMed

15. Palfrey JS, Walker DK, Haynie M, et al. Technology’s children: report of a statewide census of children dependent on medical supports. Pediatrics. 1991;87(5):611-618. PubMed

16. Feudtner C, Villareale NL, Morray B, Sharp V, Hays RM, Neff JM. Technology-dependency among patients discharged from a children’s hospital: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Pediatr. 2005;5(1):8-15. PubMed

17. Arora VM, Prochaska ML, Farnan JM, et al. Problems after discharge and understanding of communication with their primary care physicians among hospitalized seniors: a mixed methods study. J Hosp Med. 2010;5(7):385-391. PubMed

18. Brittan M, Tyler A, Martin S, et al. A Discharge Planning Template for the Electronic Medical Record Improves Scheduling of Neurology Follow-up for Comanaged Seizure Patients. Hosp Pediatr. 2014;4(6):366-371. PubMed

19. Hatoun J, Bair-Merritt M, Cabral H, Moses J. Increasing Medication Possession at Discharge for Patients With Asthma: The Meds-in-Hand Project. Pediatrics. 2016;137(3):e20150461. doi:10.1542/peds.2015-0461. PubMed

20. Berry JG, Goldmann DA, Mandl KD, et al. Health information management and perceptions of the quality of care for children with tracheotomy: a qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2011;11:117-125. PubMed

21. Berry JG, Ziniel SI, Freeman L, et al. Hospital readmission and parent perceptions of their child’s hospital discharge. Int J Qual Health Care. 2013;25(5):573-581. PubMed

22. Carusone SC, O’Leary B, McWatt S, Stewart A, Craig S, Brennan DJ. The Lived Experience of the Hospital Discharge “Plan”: A Longitudinal Qualitative Study of Complex Patients. J Hosp Med. 2017;12(1):5-10. PubMed

23. Leyenaar JK, O’Brien ER, Leslie LK, Lindenauer PK, Mangione-Smith RM. Families’ Priorities Regarding Hospital-to-Home Transitions for Children With Medical Complexity. Pediatrics. 2017;139(1):e20161581. doi:10.1542/peds.2016-1581. PubMed

© 2018 Society of Hospital Medicine

Empiric <i>Listeria monocytogenes</i> antibiotic coverage for febrile infants (age, 0-90 days)

The “Things We Do for No Reason” series reviews practices which have become common parts of hospital care but which may provide little value to our patients. Practices reviewed in the TWDFNR series do not represent “black and white” conclusions or clinical practice standards, but are meant as a starting place for research and active discussions among hospitalists and patients. We invite you to be part of that discussion. https://www.choosingwisely.org/

Evaluation and treatment of the febrile infant 0 to 90 days of age are common clinical issues in pediatrics, family medicine, emergency medicine, and pediatric hospital medicine. Traditional teaching has been that Listeria monocytogenes is 1 of the 3 most common pathogens causing neonatal sepsis. Many practitioners routinely use antibiotic regimens, including ampicillin, to specifically target Listeria. However, a large body of evidence, including a meta-analysis and several multicenter studies, has shown that listeriosis is extremely rare in the United States. The practice of empiric ampicillin thus exposes the patient to harms and costs with little if any potential benefit, while increasing pressure on the bacterial flora in the community to generate antibiotic resistance. Empiric ampicillin for all infants admitted for sepsis evaluation is a tradition-based practice no longer founded on the best available evidence.

CASE REPORT

A 32-day-old, full-term, previously healthy girl presented with fever of 1 day’s duration. Her parents reported she had appeared well until the evening before admission, when she became a bit less active and spent less time breastfeeding. The morning of admission, she was fussier than usual. Rectal temperature, taken by her parents, was 101°F. There were no other symptoms and no sick contacts.

On examination, the patient’s rectal temperature was 101.5°F. Her other vitals and the physical examination findings were unremarkable. Laboratory test results included a normal urinalysis and a peripheral white blood cell (WBC) count of 21,300 cells/µL. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis revealed normal protein and glucose levels with 3 WBCs/µL and a negative gram stain. Due to stratifying at higher risk for serious bacterial infection (SBI), the child was admitted and started on ampicillin and cefotaxime while awaiting culture results.

BACKGROUND

Evaluation and treatment of febrile infants are common clinical issues in pediatrics, emergency medicine, and general practice. Practice guidelines for evaluation of febrile infants recommend hospitalization and parenteral antibiotics for children younger than 28 days and children 29 to 90 days old if stratified at high risk for SBI.1,2 Recommendations for empiric antibiotic regimens include ampicillin in addition to either gentamicin or cefotaxime.1,2

WHY YOU MIGHT THINK AMPICILLIN IS HELPFUL

Generations of pediatrics students have been taught that the 3 pathogens most likely to cause bacterial sepsis in infants are group B Streptococcus (GBS), Escherichia coli, and Listeria monocytogenes. This teaching is still espoused in the latest editions of pediatrics textbooks.3 Ampicillin is specifically recommended for covering Listeria, and studies have found that 62% to 78% of practitioners choose empiric ampicillin-containing antibiotic regimens for the treatment of febrile infants.4-6

WHY EMPIRIC AMPICILLIN IS UNNECESSARY

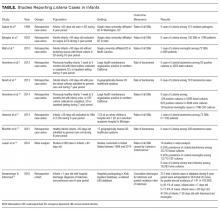

In the past, Listeria was a potential though still uncommon infant pathogen. Over the past few decades, however, the epidemiology of infant sepsis has changed significantly. Estimates of the rate of infection with Listeria now range from extremely rare to nonexistent across multiple studies4,7-15 (Table). In a 4-year retrospective case series at a single urban academic center in Washington, DC, Sadow et al.4 reported no instances of Listeria among 121 positive bacterial cultures in infants younger than 60 days seen in the emergency department (ED). Byington et al.7 examined all positive cultures for infants 0 to 90 days old at a large academic referral center in Utah over a 3-year period and reported no cases of Listeria (1298 patients, 105 SBI cases). A study at a North Carolina academic center found 1 case of Listeria meningitis among 72 SBIs (668 febrile infants) without a localizing source.8 At a large group-practice in northern California, Greenhow et al.9 examined all blood cultures (N = 4255) performed over 4 years for otherwise healthy infants 1 week to 3 months old and found no cases of Listeria. In a follow-up study, the same authors examined all blood (n = 5396), urine (n = 4599), and CSF (n = 1796) cultures in the same population and found no Listeria cases.10 Hassoun et al.11 studied SBI rates among infants younger than 28 days with any blood, urine, or CSF culture performed over 4 years at two Michigan EDs. One (0.08%) of the 1192 infants evaluated had bacteremia caused by Listeria.

Multicenter studies have reported similar results. In a study of 6 hospital systems in geographically diverse areas of the United States, Biondi et al.12 examined all positive blood cultures (N = 181) for febrile infants younger than 90 days admitted to a general pediatric ward, and found no listeriosis. Mischler et al.13 examined all positive blood cultures (N = 392) for otherwise healthy febrile infants 0 to 90 days old admitted to a hospital in 1 of 17 geographically diverse healthcare systems and found no cases of Listeria. A recent meta-analysis of studies that reported SBI rates for febrile infants 0 to 90 days old found the weighted prevalence of Listeria bacteremia to be 0.03% (2/20,703) and that of meningitis to be 0.02% (3/13,375).14 Veesenmeyer and Edmonson15 used a national inpatient database to identify all Listeria cases among infants over a 6-year period and estimated listeriosis rates for the US population. Over the 6 years, there were 212 total cases, which were extrapolated to 344 in the United States during that period, yielding a pooled annual incidence rate of 1.41 in 100,000 births.

Ampicillin offers no significant improvement in coverage for GBS or E coli beyond other β-lactam antibiotics, such as cefotaxime. Therefore, though the cost and potential harms of 24 to 48 hours of intravenous ampicillin are low for the individual patient, there is almost no potential benefit. Using the weighted prevalence of 0.03% for Listeria bacteremia reported in the recent meta-analysis,14 the number needed to treat to cover 1 case of Listeria bacteremia would be 3333. In addition, the increasing incidence of ampicillin resistance, particularly among gram-negative organisms,4,7,9 argues strongly for better antibiotic stewardship on a national level. A number of expert authors have advocated dropping empiric Listeria coverage as part of the treatment of febrile infants, particularly infants 29 to 90 days old.16,17 Some authors continue to advocate empiric Listeria coverage.6 It is interesting to note, however, that the incidence of Staph aureus bacteremia in recent case series is much higher than that reported for Listeria, accounting for 6-9% of bacteremia cases.9,11,13 Yet few if any authors advocate for empiric S. aureus coverage.

WHEN EMPIRIC AMPICILLIN COVERAGE MAY BE REASONABLE

The rate of listeriosis remains low across age groups in recent studies, but the rate is slightly higher in very young infants. In the recent national database study of listeriosis cases over a 6-year period, almost half involved infants younger than 7 days, and most of these infants showed no evidence of meningitis.15 Therefore, it may be reasonable to include empiric Listeria coverage in febrile infants younger than 7 days, though the study authors estimated 22.5 annual cases of Listeria in this age range in the United States. Eighty percent of the Listeria cases were in infants younger than 28 days, but more than 85% of infants 7 to 28 days old had meningitis. Therefore, broad antimicrobial coverage for infants with CSF pleocytosis and/or a high bacterial meningitis score is reasonable, especially for infants younger than 28 days.

Other potential indications for ampicillin are enterococcal infections. Though enteroccocal SBI rates in febrile infants are also quite low,7-9,11,12 if Enterococcus were highly suspected, such as in an infant with pyuria and gram positive organisms on gram stain, ampicillin offers good additional coverage. In the case of a local outbreak of listeriosis, or a specific exposure to Listeria-contaminated products on a patient history, antibiotics with efficacy against Listeria should be used. Last, in cases in which gentamicin is used as empiric coverage for gram-negative organisms, ampicillin offers important additional coverage for GBS.

Some practitioners advocate ampicillin and gentamicin over cefotaxime regimens on the basis of an often cited study that found a survival benefit for febrile neonates in the intensive care setting.18 There are a number of reasons that this study should not influence care for typical infants admitted with possible sepsis. First, the study was retrospective and limited by its use of administrative data. The authors acknowledged that a potential explanation for their results is unmeasured confounding. Second, the patients included in the study were dramatically different from the group of well infants admitted with possible sepsis; the study included neonatal critical care unit patients treated with antibiotics within the first 3 days of life. Third, the study’s results have not been replicated in otherwise healthy febrile infants.

WHAT YOU SHOULD USE INSTEAD OF AMPICILLIN FOR EMPIRIC LISTERIA COVERAGE

For febrile children 0 to 90 days old, empiric antibiotic coverage should be aimed at covering the current predominant pathogens, which include E coli and GBS. Therefore, for most children and US regions, a third-generation cephalosporin (eg, cefotaxime) is sufficient.

RECOMMENDATIONS

- Empiric antibiotics for treatment of febrile children 0-90 days should target E. coli and GBS; a third generation cephalosporin, (e.g. cefotaxime) alone is a reasonable choice for most patients.

- Prescribing ampicillin to specifically cover Listeria is unnecessary for the vast majority of febrile infants

- Prescribing ampicillin is reasonable in certain subgroups of febrile infants: those less than seven days of age, those with evidence of bacterial meningitis (especially if also <28 days of age), those in whom enterococcal infection is strongly suspected, and those with specific Listeria exposures related to local outbreaks.

CONCLUSION

The 32-day-old infant described in the clinical scenario was at extremely low risk for listeriosis. Antibiotic coverage with a third-generation cephalosporin is sufficient for the most likely pathogens. The common practice of empirically covering Listeria in otherwise healthy febrile infants considered to be at higher risk for SBI is no longer based on best available evidence and represents overtreatment with at least theoretical harms. Avoidance of the risks associated with the side effects of antibiotics, costs saved by forgoing multiple antibiotics, a decrease in medication dosing frequency, and improved antibiotic stewardship for the general population all argue forcefully for making empiric Listeria coverage a thing of the past.

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

Do you think this is a low-value practice? Is this truly a “Thing We Do for No Reason?” Share what you do in your practice and join in the conversation online by retweeting it on Twitter (#TWDFNR) and Liking It on Facebook. We invite you to propose ideas for other “Things We Do for No Reason” topics by emailing TWDFNR@hospitalmedicine.org.

1. Baraff LJ, Bass JW, Fleisher GR, et al. Practice guideline for the management of infants and children 0 to 36 months of age with fever without source. Agency for Health Care Policy and Research. Ann Emerg Med. 1993;22(7):1198-1210. PubMed

2. American College of Emergency Physicians Clinical Policies Committee; American College of Emergency Physicians Clinical Policies Subcommittee on Pediatric Fever. Clinical policy for children younger than three years presenting to the emergency department with fever. Ann Emerg Med. 2003;42(4):530-545. PubMed

3. Nield L, Kamat D. Fever without a focus. In: Kliegman R, Stanton B, eds. Nelson’s Textbook of Pediatrics. 20th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2016.

4. Sadow KB, Derr R, Teach SJ. Bacterial infections in infants 60 days and younger: epidemiology, resistance, and implications for treatment. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1999;153(6):611-614. PubMed

5. Aronson PL, Thurm C, Alpern ER, et al. Variation in care of the febrile young infant <90 days in US pediatric emergency departments. Pediatrics. 2014;134(4):667-677. PubMed

6. Cantey JB, Lopez-Medina E, Nguyen S, Doern C, Garcia C. Empiric antibiotics for serious bacterial infection in young infants: opportunities for stewardship. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2015;31(8):568-571. PubMed

7. Byington CL, Rittichier KK, Bassett KE, et al. Serious bacterial infections in febrile infants younger than 90 days of age: the importance of ampicillin-resistant pathogens. Pediatrics. 2003;111(5 pt 1):964-968. PubMed

8. Watt K, Waddle E, Jhaveri R. Changing epidemiology of serious bacterial infections in febrile infants without localizing signs. PLoS One. 2010;5(8):e12448. PubMed

9. Greenhow TL, Hung YY, Herz AM. Changing epidemiology of bacteremia in infants aged 1 week to 3 months. Pediatrics. 2012;129(3):e590-e596. PubMed

10. Greenhow TL, Hung YY, Herz AM, Losada E, Pantell RH. The changing epidemiology of serious bacterial infections in young infants. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2014;33(6):595-599. PubMed

11. Hassoun A, Stankovic C, Rogers A, et al. Listeria and enterococcal infections in neonates 28 days of age and younger: is empiric parenteral ampicillin still indicated? Pediatr Emerg Care. 2014;30(4):240-243. PubMed

12. Biondi E, Evans R, Mischler M, et al. Epidemiology of bacteremia in febrile infants in the United States. Pediatrics. 2013;132(6):990-996. PubMed

13. Mischler M, Ryan MS, Leyenaar JK, et al. Epidemiology of bacteremia in previously healthy febrile infants: a follow-up study. Hosp Pediatr. 2015;5(6):293-300. PubMed

14. Leazer R, Perkins AM, Shomaker K, Fine B. A meta-analysis of the rates of Listeria monocytogenes and Enterococcus in febrile infants. Hosp Pediatr. 2016;6(4):187-195. PubMed

15. Veesenmeyer AF, Edmonson MB. Trends in US hospital stays for listeriosis in infants. Hosp Pediatr. 2016;6(4):196-203. PubMed

16. Schroeder AR, Roberts KB. Is tradition trumping evidence in the treatment of young, febrile infants? Hosp Pediatr. 2016;6(4):252-253. PubMed

17. Cioffredi LA, Jhaveri R. Evaluation and management of febrile children: a review. JAMA Pediatr. 2016;170(8):794-800. PubMed

18. Clark RH, Bloom BT, Spitzer AR, Gerstmann DR. Empiric use of ampicillin and cefotaxime, compared with ampicillin and gentamicin, for neonates at risk for sepsis is associated with an increased risk of neonatal death. Pediatrics. 2006;117(1):67-74. PubMed

The “Things We Do for No Reason” series reviews practices which have become common parts of hospital care but which may provide little value to our patients. Practices reviewed in the TWDFNR series do not represent “black and white” conclusions or clinical practice standards, but are meant as a starting place for research and active discussions among hospitalists and patients. We invite you to be part of that discussion. https://www.choosingwisely.org/

Evaluation and treatment of the febrile infant 0 to 90 days of age are common clinical issues in pediatrics, family medicine, emergency medicine, and pediatric hospital medicine. Traditional teaching has been that Listeria monocytogenes is 1 of the 3 most common pathogens causing neonatal sepsis. Many practitioners routinely use antibiotic regimens, including ampicillin, to specifically target Listeria. However, a large body of evidence, including a meta-analysis and several multicenter studies, has shown that listeriosis is extremely rare in the United States. The practice of empiric ampicillin thus exposes the patient to harms and costs with little if any potential benefit, while increasing pressure on the bacterial flora in the community to generate antibiotic resistance. Empiric ampicillin for all infants admitted for sepsis evaluation is a tradition-based practice no longer founded on the best available evidence.

CASE REPORT