User login

Week in, week out for the past 25 years, I have had a front-row seat to the medical practice of a certain female physician: my wife, Heather. We met when we worked together on the wards during residency in 1991; spent a year in rural Montana working together in clinics, ERs, and hospitals; shared the care of one another’s patients as our practices grew in parallel – hers in skilled nursing facilities, mine in the hospital; and reunited in recent years to work together as part of the same practice.

When I saw the paper by Yusuke Tsugawa, MD, MPH, PhD, and his associates showing lower mortality and readmission rates for female physicians versus their male counterparts, I began to wonder if the case of Heather’s practice style, and my observations of it, could help to interpret the findings of the study (JAMA Intern Med. 2016 Dec 19. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.7875). The authors suggested that female physicians may produce better outcomes than male physicians.

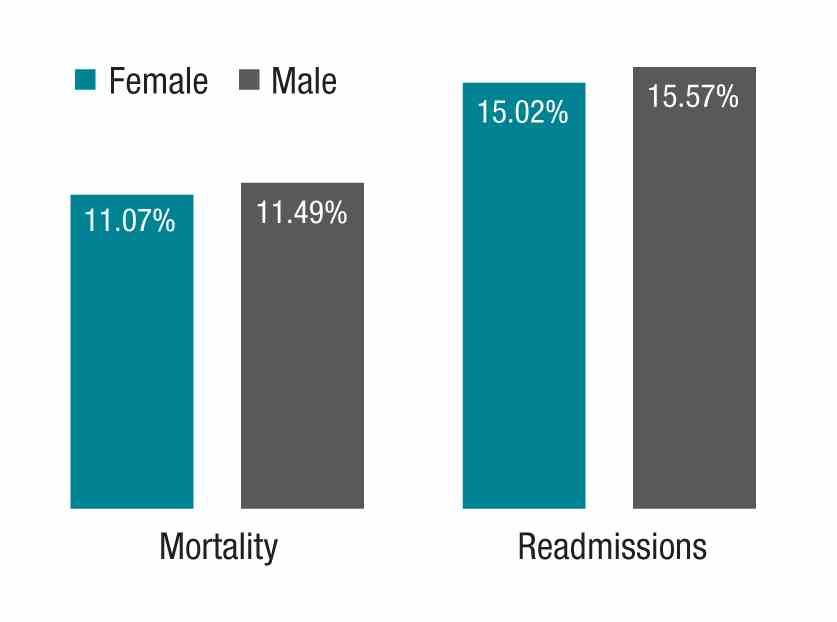

The study in question, which analyzed more than 1.5 million hospitalizations, looked at Medicare beneficiaries hospitalized with a medical condition treated by general internists between 2011 and 2014. The authors found that patients treated by female physicians had lower 30-day mortality (adjusted rate, 11.07% vs. 11.49%, P<.001) and readmissions (adjusted rate, 15.02% vs. 15.57%, P<.001) than those treated by male physicians within the same hospital. The differences were “modest but important,” coauthor Ashish K. Jha, MD, MPH, wrote in his blog. Numbers needed to treat to prevent one death and one readmission were 233 and 182, respectively.

My observations of Heather’s practice approach, compared with my own, center around three main themes:

She spends more time considering her approach to a challenging case.

She has less urgency in deciding on a definitive course of action and more patience in sorting things out before proceeding with a diagnostic and therapeutic plan. She is more likely to leave open the possibility of changing her mind; she has less of a tendency to anchor on a particular diagnosis and treatment. Put another way, she is more willing to continue with ambiguous findings without lateralizing to one particular approach.

She brings more work-life balance to her professional responsibilities.

Despite being highly productive at work (and at home), she has worked less than full time throughout her career. This means that, during any given patient encounter, she is more likely to be unburdened by overwork and its negative consequences. It is my sense that many full-time physicians would be happier (and more effective) if they simply worked less. Heather has had the self-knowledge to take on a more manageable workload; the result is that she has remained joyous in practice for more than two decades.

She is less dogmatic and more willing to customize care based on the needs of the individual patient.

Although a good fund of knowledge is essential, if such knowledge obscures the physician’s ability to read the patient, then it is best abandoned, at least temporarily. Heather refers to the body of scientific evidence frequently, but she reserves an equal or greater portion of her cognitive bandwidth for the patient she is caring for at a particular moment.

How might the observations of this case study help to derive meaning from the study by Dr. Tsugawa and his associates, so that all patients may benefit from whatever it is that female physicians do to achieve better outcomes?

First, if physicians – regardless of gender – simply have an awareness of anchoring bias or rushing to land on a diagnosis or treatment, they will be less likely to do so in the future.

Next, we can learn that avoiding overwork can make for more joy in work, and if this is so, our patients may fare better. When I say “avoiding overwork,” that might mean rethinking our assumptions underlying the amount of work we take on.

Finally, while amassing a large fund of knowledge is a good thing, balancing medical knowledge with knowledge of the individual patient is crucial to good medical practice.

Dr. Whitcomb is Chief Medical Officer at Remedy Partners in Darien, CT. He is a cofounder and past president of SHM. Email him at wfwhit@comcast.net.

Week in, week out for the past 25 years, I have had a front-row seat to the medical practice of a certain female physician: my wife, Heather. We met when we worked together on the wards during residency in 1991; spent a year in rural Montana working together in clinics, ERs, and hospitals; shared the care of one another’s patients as our practices grew in parallel – hers in skilled nursing facilities, mine in the hospital; and reunited in recent years to work together as part of the same practice.

When I saw the paper by Yusuke Tsugawa, MD, MPH, PhD, and his associates showing lower mortality and readmission rates for female physicians versus their male counterparts, I began to wonder if the case of Heather’s practice style, and my observations of it, could help to interpret the findings of the study (JAMA Intern Med. 2016 Dec 19. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.7875). The authors suggested that female physicians may produce better outcomes than male physicians.

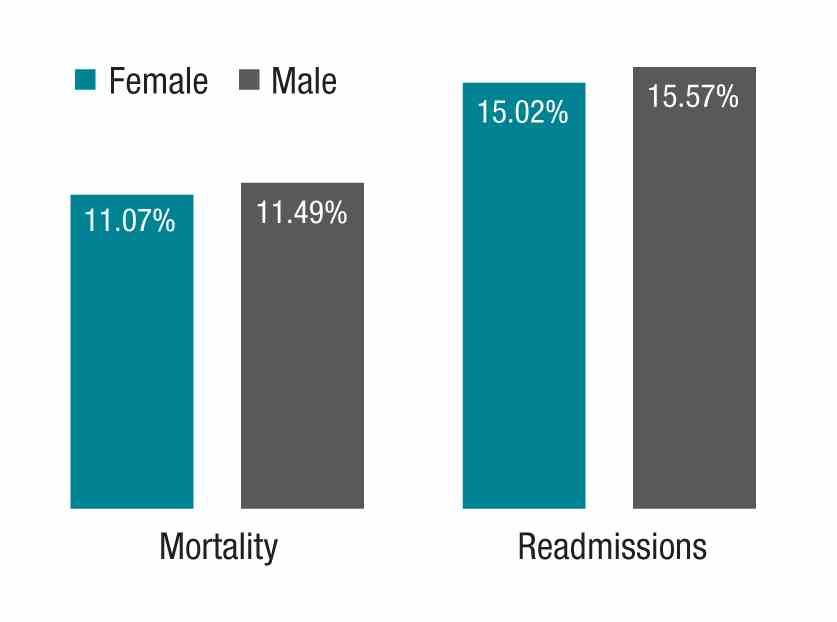

The study in question, which analyzed more than 1.5 million hospitalizations, looked at Medicare beneficiaries hospitalized with a medical condition treated by general internists between 2011 and 2014. The authors found that patients treated by female physicians had lower 30-day mortality (adjusted rate, 11.07% vs. 11.49%, P<.001) and readmissions (adjusted rate, 15.02% vs. 15.57%, P<.001) than those treated by male physicians within the same hospital. The differences were “modest but important,” coauthor Ashish K. Jha, MD, MPH, wrote in his blog. Numbers needed to treat to prevent one death and one readmission were 233 and 182, respectively.

My observations of Heather’s practice approach, compared with my own, center around three main themes:

She spends more time considering her approach to a challenging case.

She has less urgency in deciding on a definitive course of action and more patience in sorting things out before proceeding with a diagnostic and therapeutic plan. She is more likely to leave open the possibility of changing her mind; she has less of a tendency to anchor on a particular diagnosis and treatment. Put another way, she is more willing to continue with ambiguous findings without lateralizing to one particular approach.

She brings more work-life balance to her professional responsibilities.

Despite being highly productive at work (and at home), she has worked less than full time throughout her career. This means that, during any given patient encounter, she is more likely to be unburdened by overwork and its negative consequences. It is my sense that many full-time physicians would be happier (and more effective) if they simply worked less. Heather has had the self-knowledge to take on a more manageable workload; the result is that she has remained joyous in practice for more than two decades.

She is less dogmatic and more willing to customize care based on the needs of the individual patient.

Although a good fund of knowledge is essential, if such knowledge obscures the physician’s ability to read the patient, then it is best abandoned, at least temporarily. Heather refers to the body of scientific evidence frequently, but she reserves an equal or greater portion of her cognitive bandwidth for the patient she is caring for at a particular moment.

How might the observations of this case study help to derive meaning from the study by Dr. Tsugawa and his associates, so that all patients may benefit from whatever it is that female physicians do to achieve better outcomes?

First, if physicians – regardless of gender – simply have an awareness of anchoring bias or rushing to land on a diagnosis or treatment, they will be less likely to do so in the future.

Next, we can learn that avoiding overwork can make for more joy in work, and if this is so, our patients may fare better. When I say “avoiding overwork,” that might mean rethinking our assumptions underlying the amount of work we take on.

Finally, while amassing a large fund of knowledge is a good thing, balancing medical knowledge with knowledge of the individual patient is crucial to good medical practice.

Dr. Whitcomb is Chief Medical Officer at Remedy Partners in Darien, CT. He is a cofounder and past president of SHM. Email him at wfwhit@comcast.net.

Week in, week out for the past 25 years, I have had a front-row seat to the medical practice of a certain female physician: my wife, Heather. We met when we worked together on the wards during residency in 1991; spent a year in rural Montana working together in clinics, ERs, and hospitals; shared the care of one another’s patients as our practices grew in parallel – hers in skilled nursing facilities, mine in the hospital; and reunited in recent years to work together as part of the same practice.

When I saw the paper by Yusuke Tsugawa, MD, MPH, PhD, and his associates showing lower mortality and readmission rates for female physicians versus their male counterparts, I began to wonder if the case of Heather’s practice style, and my observations of it, could help to interpret the findings of the study (JAMA Intern Med. 2016 Dec 19. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.7875). The authors suggested that female physicians may produce better outcomes than male physicians.

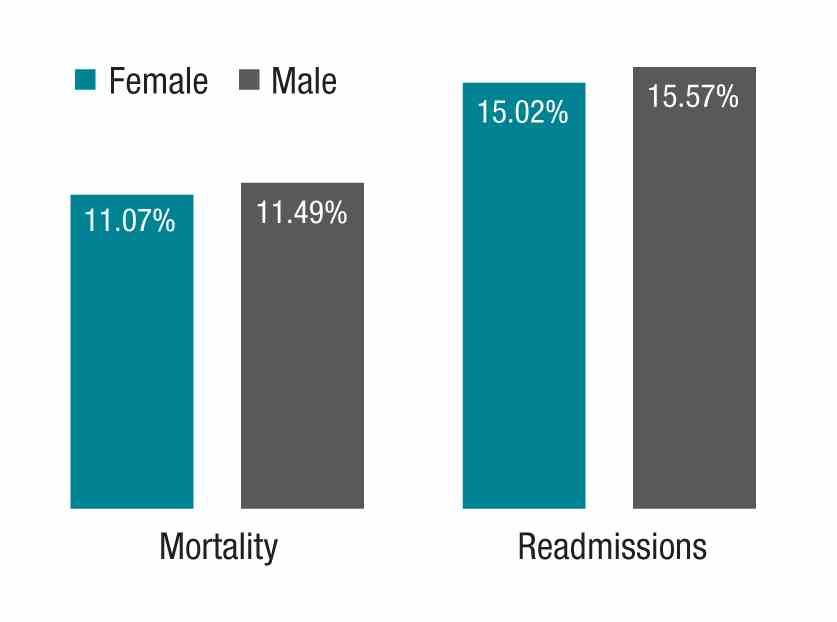

The study in question, which analyzed more than 1.5 million hospitalizations, looked at Medicare beneficiaries hospitalized with a medical condition treated by general internists between 2011 and 2014. The authors found that patients treated by female physicians had lower 30-day mortality (adjusted rate, 11.07% vs. 11.49%, P<.001) and readmissions (adjusted rate, 15.02% vs. 15.57%, P<.001) than those treated by male physicians within the same hospital. The differences were “modest but important,” coauthor Ashish K. Jha, MD, MPH, wrote in his blog. Numbers needed to treat to prevent one death and one readmission were 233 and 182, respectively.

My observations of Heather’s practice approach, compared with my own, center around three main themes:

She spends more time considering her approach to a challenging case.

She has less urgency in deciding on a definitive course of action and more patience in sorting things out before proceeding with a diagnostic and therapeutic plan. She is more likely to leave open the possibility of changing her mind; she has less of a tendency to anchor on a particular diagnosis and treatment. Put another way, she is more willing to continue with ambiguous findings without lateralizing to one particular approach.

She brings more work-life balance to her professional responsibilities.

Despite being highly productive at work (and at home), she has worked less than full time throughout her career. This means that, during any given patient encounter, she is more likely to be unburdened by overwork and its negative consequences. It is my sense that many full-time physicians would be happier (and more effective) if they simply worked less. Heather has had the self-knowledge to take on a more manageable workload; the result is that she has remained joyous in practice for more than two decades.

She is less dogmatic and more willing to customize care based on the needs of the individual patient.

Although a good fund of knowledge is essential, if such knowledge obscures the physician’s ability to read the patient, then it is best abandoned, at least temporarily. Heather refers to the body of scientific evidence frequently, but she reserves an equal or greater portion of her cognitive bandwidth for the patient she is caring for at a particular moment.

How might the observations of this case study help to derive meaning from the study by Dr. Tsugawa and his associates, so that all patients may benefit from whatever it is that female physicians do to achieve better outcomes?

First, if physicians – regardless of gender – simply have an awareness of anchoring bias or rushing to land on a diagnosis or treatment, they will be less likely to do so in the future.

Next, we can learn that avoiding overwork can make for more joy in work, and if this is so, our patients may fare better. When I say “avoiding overwork,” that might mean rethinking our assumptions underlying the amount of work we take on.

Finally, while amassing a large fund of knowledge is a good thing, balancing medical knowledge with knowledge of the individual patient is crucial to good medical practice.

Dr. Whitcomb is Chief Medical Officer at Remedy Partners in Darien, CT. He is a cofounder and past president of SHM. Email him at wfwhit@comcast.net.