User login

Dr. Whitcomb is chief medical officer of Remedy Partners. He is co-founder and past president of SHM. E-mail him at wfwhit@comcast.net.

Female physicians, lower mortality, lower readmissions: A case study

Week in, week out for the past 25 years, I have had a front-row seat to the medical practice of a certain female physician: my wife, Heather. We met when we worked together on the wards during residency in 1991; spent a year in rural Montana working together in clinics, ERs, and hospitals; shared the care of one another’s patients as our practices grew in parallel – hers in skilled nursing facilities, mine in the hospital; and reunited in recent years to work together as part of the same practice.

When I saw the paper by Yusuke Tsugawa, MD, MPH, PhD, and his associates showing lower mortality and readmission rates for female physicians versus their male counterparts, I began to wonder if the case of Heather’s practice style, and my observations of it, could help to interpret the findings of the study (JAMA Intern Med. 2016 Dec 19. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.7875). The authors suggested that female physicians may produce better outcomes than male physicians.

The study in question, which analyzed more than 1.5 million hospitalizations, looked at Medicare beneficiaries hospitalized with a medical condition treated by general internists between 2011 and 2014. The authors found that patients treated by female physicians had lower 30-day mortality (adjusted rate, 11.07% vs. 11.49%, P<.001) and readmissions (adjusted rate, 15.02% vs. 15.57%, P<.001) than those treated by male physicians within the same hospital. The differences were “modest but important,” coauthor Ashish K. Jha, MD, MPH, wrote in his blog. Numbers needed to treat to prevent one death and one readmission were 233 and 182, respectively.

My observations of Heather’s practice approach, compared with my own, center around three main themes:

She spends more time considering her approach to a challenging case.

She has less urgency in deciding on a definitive course of action and more patience in sorting things out before proceeding with a diagnostic and therapeutic plan. She is more likely to leave open the possibility of changing her mind; she has less of a tendency to anchor on a particular diagnosis and treatment. Put another way, she is more willing to continue with ambiguous findings without lateralizing to one particular approach.

She brings more work-life balance to her professional responsibilities.

Despite being highly productive at work (and at home), she has worked less than full time throughout her career. This means that, during any given patient encounter, she is more likely to be unburdened by overwork and its negative consequences. It is my sense that many full-time physicians would be happier (and more effective) if they simply worked less. Heather has had the self-knowledge to take on a more manageable workload; the result is that she has remained joyous in practice for more than two decades.

She is less dogmatic and more willing to customize care based on the needs of the individual patient.

Although a good fund of knowledge is essential, if such knowledge obscures the physician’s ability to read the patient, then it is best abandoned, at least temporarily. Heather refers to the body of scientific evidence frequently, but she reserves an equal or greater portion of her cognitive bandwidth for the patient she is caring for at a particular moment.

How might the observations of this case study help to derive meaning from the study by Dr. Tsugawa and his associates, so that all patients may benefit from whatever it is that female physicians do to achieve better outcomes?

First, if physicians – regardless of gender – simply have an awareness of anchoring bias or rushing to land on a diagnosis or treatment, they will be less likely to do so in the future.

Next, we can learn that avoiding overwork can make for more joy in work, and if this is so, our patients may fare better. When I say “avoiding overwork,” that might mean rethinking our assumptions underlying the amount of work we take on.

Finally, while amassing a large fund of knowledge is a good thing, balancing medical knowledge with knowledge of the individual patient is crucial to good medical practice.

Dr. Whitcomb is Chief Medical Officer at Remedy Partners in Darien, CT. He is a cofounder and past president of SHM. Email him at wfwhit@comcast.net.

Week in, week out for the past 25 years, I have had a front-row seat to the medical practice of a certain female physician: my wife, Heather. We met when we worked together on the wards during residency in 1991; spent a year in rural Montana working together in clinics, ERs, and hospitals; shared the care of one another’s patients as our practices grew in parallel – hers in skilled nursing facilities, mine in the hospital; and reunited in recent years to work together as part of the same practice.

When I saw the paper by Yusuke Tsugawa, MD, MPH, PhD, and his associates showing lower mortality and readmission rates for female physicians versus their male counterparts, I began to wonder if the case of Heather’s practice style, and my observations of it, could help to interpret the findings of the study (JAMA Intern Med. 2016 Dec 19. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.7875). The authors suggested that female physicians may produce better outcomes than male physicians.

The study in question, which analyzed more than 1.5 million hospitalizations, looked at Medicare beneficiaries hospitalized with a medical condition treated by general internists between 2011 and 2014. The authors found that patients treated by female physicians had lower 30-day mortality (adjusted rate, 11.07% vs. 11.49%, P<.001) and readmissions (adjusted rate, 15.02% vs. 15.57%, P<.001) than those treated by male physicians within the same hospital. The differences were “modest but important,” coauthor Ashish K. Jha, MD, MPH, wrote in his blog. Numbers needed to treat to prevent one death and one readmission were 233 and 182, respectively.

My observations of Heather’s practice approach, compared with my own, center around three main themes:

She spends more time considering her approach to a challenging case.

She has less urgency in deciding on a definitive course of action and more patience in sorting things out before proceeding with a diagnostic and therapeutic plan. She is more likely to leave open the possibility of changing her mind; she has less of a tendency to anchor on a particular diagnosis and treatment. Put another way, she is more willing to continue with ambiguous findings without lateralizing to one particular approach.

She brings more work-life balance to her professional responsibilities.

Despite being highly productive at work (and at home), she has worked less than full time throughout her career. This means that, during any given patient encounter, she is more likely to be unburdened by overwork and its negative consequences. It is my sense that many full-time physicians would be happier (and more effective) if they simply worked less. Heather has had the self-knowledge to take on a more manageable workload; the result is that she has remained joyous in practice for more than two decades.

She is less dogmatic and more willing to customize care based on the needs of the individual patient.

Although a good fund of knowledge is essential, if such knowledge obscures the physician’s ability to read the patient, then it is best abandoned, at least temporarily. Heather refers to the body of scientific evidence frequently, but she reserves an equal or greater portion of her cognitive bandwidth for the patient she is caring for at a particular moment.

How might the observations of this case study help to derive meaning from the study by Dr. Tsugawa and his associates, so that all patients may benefit from whatever it is that female physicians do to achieve better outcomes?

First, if physicians – regardless of gender – simply have an awareness of anchoring bias or rushing to land on a diagnosis or treatment, they will be less likely to do so in the future.

Next, we can learn that avoiding overwork can make for more joy in work, and if this is so, our patients may fare better. When I say “avoiding overwork,” that might mean rethinking our assumptions underlying the amount of work we take on.

Finally, while amassing a large fund of knowledge is a good thing, balancing medical knowledge with knowledge of the individual patient is crucial to good medical practice.

Dr. Whitcomb is Chief Medical Officer at Remedy Partners in Darien, CT. He is a cofounder and past president of SHM. Email him at wfwhit@comcast.net.

Week in, week out for the past 25 years, I have had a front-row seat to the medical practice of a certain female physician: my wife, Heather. We met when we worked together on the wards during residency in 1991; spent a year in rural Montana working together in clinics, ERs, and hospitals; shared the care of one another’s patients as our practices grew in parallel – hers in skilled nursing facilities, mine in the hospital; and reunited in recent years to work together as part of the same practice.

When I saw the paper by Yusuke Tsugawa, MD, MPH, PhD, and his associates showing lower mortality and readmission rates for female physicians versus their male counterparts, I began to wonder if the case of Heather’s practice style, and my observations of it, could help to interpret the findings of the study (JAMA Intern Med. 2016 Dec 19. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.7875). The authors suggested that female physicians may produce better outcomes than male physicians.

The study in question, which analyzed more than 1.5 million hospitalizations, looked at Medicare beneficiaries hospitalized with a medical condition treated by general internists between 2011 and 2014. The authors found that patients treated by female physicians had lower 30-day mortality (adjusted rate, 11.07% vs. 11.49%, P<.001) and readmissions (adjusted rate, 15.02% vs. 15.57%, P<.001) than those treated by male physicians within the same hospital. The differences were “modest but important,” coauthor Ashish K. Jha, MD, MPH, wrote in his blog. Numbers needed to treat to prevent one death and one readmission were 233 and 182, respectively.

My observations of Heather’s practice approach, compared with my own, center around three main themes:

She spends more time considering her approach to a challenging case.

She has less urgency in deciding on a definitive course of action and more patience in sorting things out before proceeding with a diagnostic and therapeutic plan. She is more likely to leave open the possibility of changing her mind; she has less of a tendency to anchor on a particular diagnosis and treatment. Put another way, she is more willing to continue with ambiguous findings without lateralizing to one particular approach.

She brings more work-life balance to her professional responsibilities.

Despite being highly productive at work (and at home), she has worked less than full time throughout her career. This means that, during any given patient encounter, she is more likely to be unburdened by overwork and its negative consequences. It is my sense that many full-time physicians would be happier (and more effective) if they simply worked less. Heather has had the self-knowledge to take on a more manageable workload; the result is that she has remained joyous in practice for more than two decades.

She is less dogmatic and more willing to customize care based on the needs of the individual patient.

Although a good fund of knowledge is essential, if such knowledge obscures the physician’s ability to read the patient, then it is best abandoned, at least temporarily. Heather refers to the body of scientific evidence frequently, but she reserves an equal or greater portion of her cognitive bandwidth for the patient she is caring for at a particular moment.

How might the observations of this case study help to derive meaning from the study by Dr. Tsugawa and his associates, so that all patients may benefit from whatever it is that female physicians do to achieve better outcomes?

First, if physicians – regardless of gender – simply have an awareness of anchoring bias or rushing to land on a diagnosis or treatment, they will be less likely to do so in the future.

Next, we can learn that avoiding overwork can make for more joy in work, and if this is so, our patients may fare better. When I say “avoiding overwork,” that might mean rethinking our assumptions underlying the amount of work we take on.

Finally, while amassing a large fund of knowledge is a good thing, balancing medical knowledge with knowledge of the individual patient is crucial to good medical practice.

Dr. Whitcomb is Chief Medical Officer at Remedy Partners in Darien, CT. He is a cofounder and past president of SHM. Email him at wfwhit@comcast.net.

Thinking Outside the DRG Box

When choosing quality improvement activities, hospitalists have no shortage of choices. In this column, I offer a strategic guide for hospitalists as they assess where best to spend their energy as the shift to value-based care progresses. This includes the introduction of MACRA, the landmark new payment program for doctors and other clinicians (aka the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015), with its incentives for participation in alternative payment models.

Since 1983, Medicare has reimbursed hospitals using a lump-sum payment known as a diagnosis-related group, or DRG. Since then, hospitals have focused a good deal of their energy on removing needless expenses from the hospitalization to improve their bottom line, recognizing the DRG payment they receive is relatively fixed. To this end, a major strategy has been to use hospitalists to decrease length of stay and “right size” the utilization of in-hospital tests and treatments.

However, things are changing as we enter the era of alternative payment models such as accountable care organizations (ACOs) and bundled payments. The lens Medicare (and, to a great extent, commercial payors) peers through to assess inpatient hospital costs is the DRG payment amount. Beyond that, Medicare has little visibility into the actual costs hospitals incur. Since hospital spending equates to the payment amount for a DRG, it becomes apparent that the incremental opportunity for hospitalists to improve value (quality divided by cost) in alternative payment models stems from payments outside the DRG. Such payments include those related to the post-acute period such as nursing and rehabilitation facilities, readmissions, and part B activity (e.g., consultants and outpatient tests).

What does this mean for hospitalists? MACRA begins in 2019, but initial payments will be based on 2017 performance. The associated advantage of participating in an “advanced alternative payment model” where there is accountability for care beyond the hospitalization is that hospitalists will be rewarded for taking costs out of the post-acute time period.

To be clear, hospitalists should remain agents of in-hospital efficiency and quality. After all, that is how we add value to the hospitals in which we practice. All things being equal, however, hospitalists should focus on practices that will improve value beyond the four walls of the hospital.

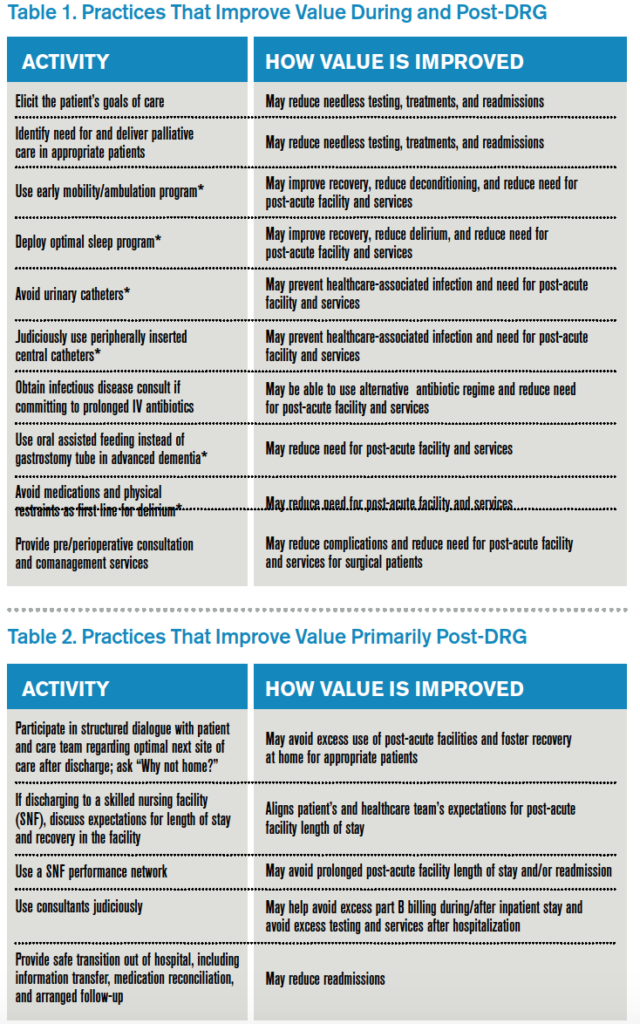

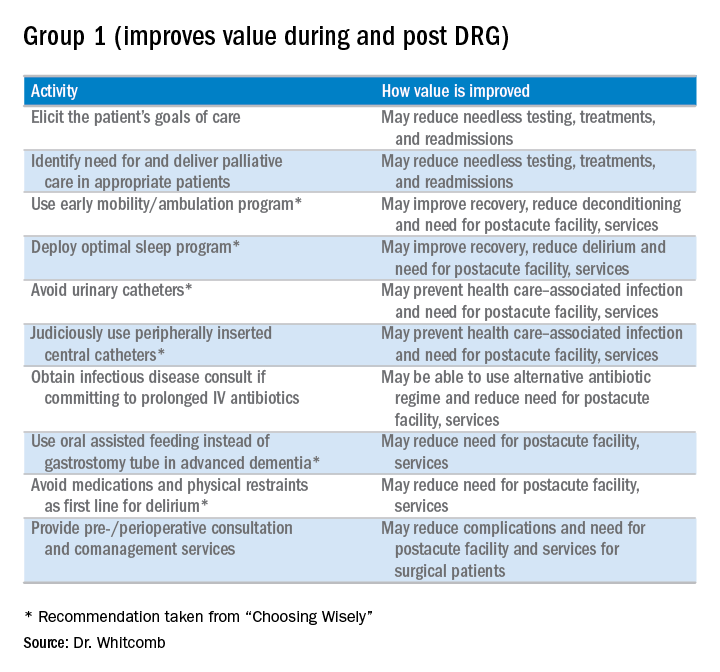

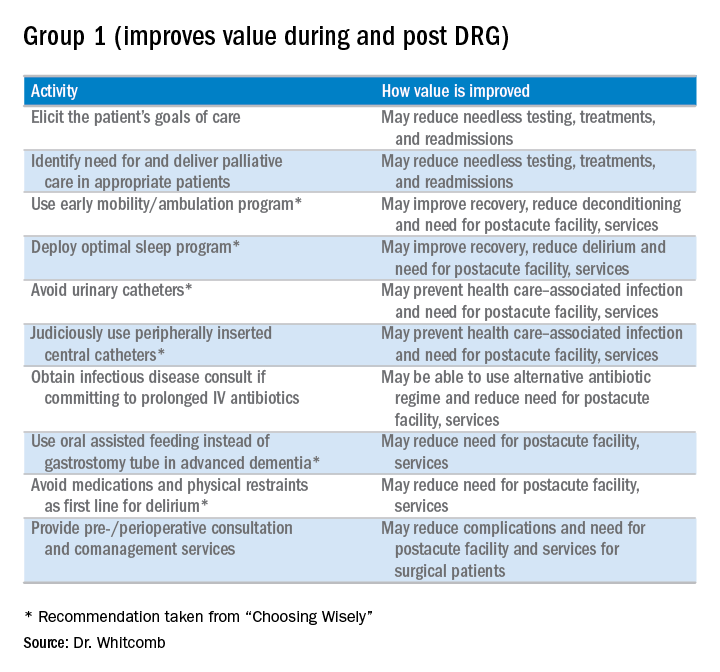

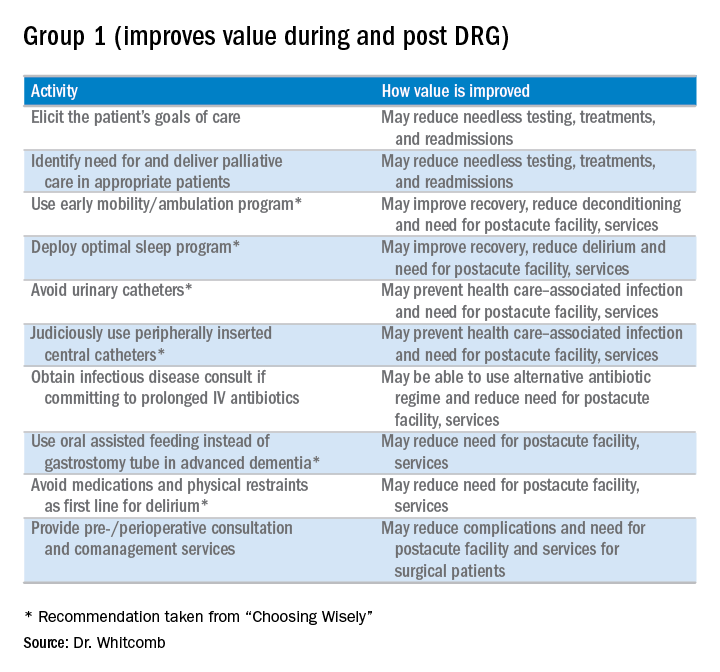

Here is my shortlist of these practices. While there is crossover between the categories, I divide the practices into those that improve value during the DRG period and also post-DRG and those that improve value primarily post-DRG (thanks to Choosing Wisely for contributing to the recommendations with an asterisk1):

Thinking outside the DRG box will require an adjustment to the approach taken by hospitalists because the current demands are often more than enough for a day’s work. Hospitalists will be called upon to innovate and fashion better approaches to care. This will require support by other members of the healthcare team so hospitalists can work smarter, not harder, to meet the requirements of a changing healthcare system. A prerequisite is better payment models that align financial incentives so that providing higher-value care is sustainable and appropriately rewarded.

Reference

Clinician lists. Choosing Wisely website. Accessed October 25, 2016.

When choosing quality improvement activities, hospitalists have no shortage of choices. In this column, I offer a strategic guide for hospitalists as they assess where best to spend their energy as the shift to value-based care progresses. This includes the introduction of MACRA, the landmark new payment program for doctors and other clinicians (aka the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015), with its incentives for participation in alternative payment models.

Since 1983, Medicare has reimbursed hospitals using a lump-sum payment known as a diagnosis-related group, or DRG. Since then, hospitals have focused a good deal of their energy on removing needless expenses from the hospitalization to improve their bottom line, recognizing the DRG payment they receive is relatively fixed. To this end, a major strategy has been to use hospitalists to decrease length of stay and “right size” the utilization of in-hospital tests and treatments.

However, things are changing as we enter the era of alternative payment models such as accountable care organizations (ACOs) and bundled payments. The lens Medicare (and, to a great extent, commercial payors) peers through to assess inpatient hospital costs is the DRG payment amount. Beyond that, Medicare has little visibility into the actual costs hospitals incur. Since hospital spending equates to the payment amount for a DRG, it becomes apparent that the incremental opportunity for hospitalists to improve value (quality divided by cost) in alternative payment models stems from payments outside the DRG. Such payments include those related to the post-acute period such as nursing and rehabilitation facilities, readmissions, and part B activity (e.g., consultants and outpatient tests).

What does this mean for hospitalists? MACRA begins in 2019, but initial payments will be based on 2017 performance. The associated advantage of participating in an “advanced alternative payment model” where there is accountability for care beyond the hospitalization is that hospitalists will be rewarded for taking costs out of the post-acute time period.

To be clear, hospitalists should remain agents of in-hospital efficiency and quality. After all, that is how we add value to the hospitals in which we practice. All things being equal, however, hospitalists should focus on practices that will improve value beyond the four walls of the hospital.

Here is my shortlist of these practices. While there is crossover between the categories, I divide the practices into those that improve value during the DRG period and also post-DRG and those that improve value primarily post-DRG (thanks to Choosing Wisely for contributing to the recommendations with an asterisk1):

Thinking outside the DRG box will require an adjustment to the approach taken by hospitalists because the current demands are often more than enough for a day’s work. Hospitalists will be called upon to innovate and fashion better approaches to care. This will require support by other members of the healthcare team so hospitalists can work smarter, not harder, to meet the requirements of a changing healthcare system. A prerequisite is better payment models that align financial incentives so that providing higher-value care is sustainable and appropriately rewarded.

Reference

Clinician lists. Choosing Wisely website. Accessed October 25, 2016.

When choosing quality improvement activities, hospitalists have no shortage of choices. In this column, I offer a strategic guide for hospitalists as they assess where best to spend their energy as the shift to value-based care progresses. This includes the introduction of MACRA, the landmark new payment program for doctors and other clinicians (aka the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015), with its incentives for participation in alternative payment models.

Since 1983, Medicare has reimbursed hospitals using a lump-sum payment known as a diagnosis-related group, or DRG. Since then, hospitals have focused a good deal of their energy on removing needless expenses from the hospitalization to improve their bottom line, recognizing the DRG payment they receive is relatively fixed. To this end, a major strategy has been to use hospitalists to decrease length of stay and “right size” the utilization of in-hospital tests and treatments.

However, things are changing as we enter the era of alternative payment models such as accountable care organizations (ACOs) and bundled payments. The lens Medicare (and, to a great extent, commercial payors) peers through to assess inpatient hospital costs is the DRG payment amount. Beyond that, Medicare has little visibility into the actual costs hospitals incur. Since hospital spending equates to the payment amount for a DRG, it becomes apparent that the incremental opportunity for hospitalists to improve value (quality divided by cost) in alternative payment models stems from payments outside the DRG. Such payments include those related to the post-acute period such as nursing and rehabilitation facilities, readmissions, and part B activity (e.g., consultants and outpatient tests).

What does this mean for hospitalists? MACRA begins in 2019, but initial payments will be based on 2017 performance. The associated advantage of participating in an “advanced alternative payment model” where there is accountability for care beyond the hospitalization is that hospitalists will be rewarded for taking costs out of the post-acute time period.

To be clear, hospitalists should remain agents of in-hospital efficiency and quality. After all, that is how we add value to the hospitals in which we practice. All things being equal, however, hospitalists should focus on practices that will improve value beyond the four walls of the hospital.

Here is my shortlist of these practices. While there is crossover between the categories, I divide the practices into those that improve value during the DRG period and also post-DRG and those that improve value primarily post-DRG (thanks to Choosing Wisely for contributing to the recommendations with an asterisk1):

Thinking outside the DRG box will require an adjustment to the approach taken by hospitalists because the current demands are often more than enough for a day’s work. Hospitalists will be called upon to innovate and fashion better approaches to care. This will require support by other members of the healthcare team so hospitalists can work smarter, not harder, to meet the requirements of a changing healthcare system. A prerequisite is better payment models that align financial incentives so that providing higher-value care is sustainable and appropriately rewarded.

Reference

Clinician lists. Choosing Wisely website. Accessed October 25, 2016.

Providing Effective Palliative Care in the Era of Value

Although effective palliative care has always been a must-have for patients and caregivers facing serious illness, it hasn’t always been readily available. With the emergence of value-based healthcare models—and their potent incentives to reduce avoidable readmissions—there is renewed hope that such care will be accessible to those who need it.

Palliative and end-of-life care have long been promoted as core skills for hospitalists. The topic has regularly been included at SHM annual meetings and other prominent hospital medicine conferences, in the American Board of Internal Medicine blueprint for recognition of focused practice in hospital medicine, and in a number of influential references for hospitalists. Still, as I look at hospitalist programs around the country, there is a clear need to improve hospitalists’ delivery of palliative and end-of-life care.

Care of patients with chronic illness in their last two years of life accounts for a third of all Medicare spending.1 As hospitalists, we encounter many of these patients as they are hospitalized—and often re-hospitalized. Palliative care, which can improve quality of life and decrease costs for patients while leading to increased satisfaction and better outcomes for caregivers, can help alleviate unneeded and unwanted aggressive interventions like hospitalization.2,3

In its 2014 report, Dying in America, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) identified several areas for improvement, including better advance care planning and payment systems supporting high quality end-of-life care.4 As I write this column in mid 2016, there are two notable achievements since the IOM report: two E&M codes for advance care planning and a substantial and growing number of hospitalist patients in alternative payment models like bundled payments or ACOs.5 I believe we are entering a time when the availability of good palliative care will be accelerated due to broader forces in healthcare that for the first time align incentives between patients’ wishes and how care is paid for.

Palliative Care Skills for Hospitalists

The following are key actions for physicians in addressing palliative care for the hospitalized patient. At the risk of oversimplifying the discipline, I offer a few key actions for hospitalists to keep in mind.

Identify patients who would benefit from palliative care. The surprise question—“Would I be surprised if this patient died in the next year?”—has the ability to predict which patients would benefit from palliative care. In one observation from a group of patients with cancer, a “no” answer identified 60% of patients who died within a year.6 The surprise question has previously been shown to be predictive in other cancer and non-cancer populations.7,8

Weisman and Meier suggest using the following in a checklist at the time of hospital admission as “primary criteria to screen for unmet palliative care needs”:9

- The surprise question

- Frequent admissions

- Admission prompted by difficult-to-control physical or psychological symptoms

- Complex care requirements

- Decline in function, feeding intolerance, or unintended decline in weight

Hold a “goals of care” meeting. A notable step forward for supporting conversations between physicians and patients occurred on Jan. 1, when the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) announced the Advance Care Planning E&M codes. These are CPT codes 99497 and 99498. They can be used on the same day as other E&M codes and cover discussions regarding advance care planning issues including discussing advance directives, appointing a healthcare proxy or durable power of attorney, discussing a living will, or addressing orders for life-sustaining treatment like the role of hydration or future hospitalizations. (For more information on how to use them, visit the CMS website and search for the FAQ.)

What should hospitalists concentrate on when having “goals of care” conversations with patients and caregivers? Ariadne Labs, a Harvard-affiliated health innovation group, offers the following as elements of a serious illness conversation:10

- Patients’ understanding of their illness

- Patients’ preferences for information and for family involvement

- Personal life goals, fears, and anxieties

- Trade-offs they are willing to accept

For hospitalists, an important area to pay particular attention to is the role of future hospitalizations in patients’ wishes for care, as some patients, if offered appropriate symptom control, would prefer to remain at home.

Two other crucial elements of inpatient palliative care—offer psychosocial support and symptom relief and hand off patient to effective post-hospital palliative care—are outside the scope of this article. However, they should be kept in mind and, of course, applied.

Understand the role of the palliative care consultation. Busy hospitalists might reasonably think, “I simply don’t have time to address palliative care in patients who aren’t likely to die during this hospitalization or soon after.” The palliative care consult service, if available, should be accessed when patients are identified as palliative care candidates but the primary hospitalist does not have the time or resources—including specialized knowledge in some cases—to deliver adequate palliative care. Palliative care specialists can also help bridge the gap between inpatient and outpatient palliative care resources.

In sum, the move to value-based payment models and the new advance care planning E&M codes provide a renewed focus—with more aligned incentives—and the opportunity to provide good palliative care to all who need it.

For hospitalists, identifying those who would benefit from palliative care and working with the healthcare team to ensure the care is delivered are at the heart of our professional mission. TH

References

- End-of-life care. The Darmouth Atlas of Health Care website. Accessed June 23, 2016.

- Gade G, Venohr I, Conner D, et al. Impact of an inpatient palliative care team: a randomized control trial. J Palliat Med. 2008;11(2):180-190.

- Morrison RS, Penrod JD, Cassel JB, et al. Cost savings associated with US hospital palliative care consultation programs. Arch Int Med. 2008;168(16):1783-1790.

- Institute of Medicine. Dying in America: Improving Quality and Honoring Individual Preferences near the End of Life. 2014.

- BPCI Model 2: Retrospective acute & post acute care episode. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services website. Accessed June 24, 2016.

- Vick JB, Pertsch N, Hutchings M, et al. The utility of the surprise question in identifying patients most at risk of death. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(suppl):8.

- Moss AH, Ganjoo J, Sharma S, et al. Utility of the “surprise” question to identify dialysis patients with high mortality. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;3:1379-1384.

- Moss AH, Lunney JR, Culp S, et al. Prognostic significance of the “surprise” question in cancer patients. J Palliat Med. 2010;13(7):837-840.

- Weissman D, Meier C. Identifying patients in need of a palliative care assessment in the hospital setting: a consensus report from the Center to Advance Palliative Care. J Palliat Med. 2011;14(1):17-23.

- Serious illness care resources. Ariadne Labs website. Accessed June 24, 2016.

Although effective palliative care has always been a must-have for patients and caregivers facing serious illness, it hasn’t always been readily available. With the emergence of value-based healthcare models—and their potent incentives to reduce avoidable readmissions—there is renewed hope that such care will be accessible to those who need it.

Palliative and end-of-life care have long been promoted as core skills for hospitalists. The topic has regularly been included at SHM annual meetings and other prominent hospital medicine conferences, in the American Board of Internal Medicine blueprint for recognition of focused practice in hospital medicine, and in a number of influential references for hospitalists. Still, as I look at hospitalist programs around the country, there is a clear need to improve hospitalists’ delivery of palliative and end-of-life care.

Care of patients with chronic illness in their last two years of life accounts for a third of all Medicare spending.1 As hospitalists, we encounter many of these patients as they are hospitalized—and often re-hospitalized. Palliative care, which can improve quality of life and decrease costs for patients while leading to increased satisfaction and better outcomes for caregivers, can help alleviate unneeded and unwanted aggressive interventions like hospitalization.2,3

In its 2014 report, Dying in America, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) identified several areas for improvement, including better advance care planning and payment systems supporting high quality end-of-life care.4 As I write this column in mid 2016, there are two notable achievements since the IOM report: two E&M codes for advance care planning and a substantial and growing number of hospitalist patients in alternative payment models like bundled payments or ACOs.5 I believe we are entering a time when the availability of good palliative care will be accelerated due to broader forces in healthcare that for the first time align incentives between patients’ wishes and how care is paid for.

Palliative Care Skills for Hospitalists

The following are key actions for physicians in addressing palliative care for the hospitalized patient. At the risk of oversimplifying the discipline, I offer a few key actions for hospitalists to keep in mind.

Identify patients who would benefit from palliative care. The surprise question—“Would I be surprised if this patient died in the next year?”—has the ability to predict which patients would benefit from palliative care. In one observation from a group of patients with cancer, a “no” answer identified 60% of patients who died within a year.6 The surprise question has previously been shown to be predictive in other cancer and non-cancer populations.7,8

Weisman and Meier suggest using the following in a checklist at the time of hospital admission as “primary criteria to screen for unmet palliative care needs”:9

- The surprise question

- Frequent admissions

- Admission prompted by difficult-to-control physical or psychological symptoms

- Complex care requirements

- Decline in function, feeding intolerance, or unintended decline in weight

Hold a “goals of care” meeting. A notable step forward for supporting conversations between physicians and patients occurred on Jan. 1, when the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) announced the Advance Care Planning E&M codes. These are CPT codes 99497 and 99498. They can be used on the same day as other E&M codes and cover discussions regarding advance care planning issues including discussing advance directives, appointing a healthcare proxy or durable power of attorney, discussing a living will, or addressing orders for life-sustaining treatment like the role of hydration or future hospitalizations. (For more information on how to use them, visit the CMS website and search for the FAQ.)

What should hospitalists concentrate on when having “goals of care” conversations with patients and caregivers? Ariadne Labs, a Harvard-affiliated health innovation group, offers the following as elements of a serious illness conversation:10

- Patients’ understanding of their illness

- Patients’ preferences for information and for family involvement

- Personal life goals, fears, and anxieties

- Trade-offs they are willing to accept

For hospitalists, an important area to pay particular attention to is the role of future hospitalizations in patients’ wishes for care, as some patients, if offered appropriate symptom control, would prefer to remain at home.

Two other crucial elements of inpatient palliative care—offer psychosocial support and symptom relief and hand off patient to effective post-hospital palliative care—are outside the scope of this article. However, they should be kept in mind and, of course, applied.

Understand the role of the palliative care consultation. Busy hospitalists might reasonably think, “I simply don’t have time to address palliative care in patients who aren’t likely to die during this hospitalization or soon after.” The palliative care consult service, if available, should be accessed when patients are identified as palliative care candidates but the primary hospitalist does not have the time or resources—including specialized knowledge in some cases—to deliver adequate palliative care. Palliative care specialists can also help bridge the gap between inpatient and outpatient palliative care resources.

In sum, the move to value-based payment models and the new advance care planning E&M codes provide a renewed focus—with more aligned incentives—and the opportunity to provide good palliative care to all who need it.

For hospitalists, identifying those who would benefit from palliative care and working with the healthcare team to ensure the care is delivered are at the heart of our professional mission. TH

References

- End-of-life care. The Darmouth Atlas of Health Care website. Accessed June 23, 2016.

- Gade G, Venohr I, Conner D, et al. Impact of an inpatient palliative care team: a randomized control trial. J Palliat Med. 2008;11(2):180-190.

- Morrison RS, Penrod JD, Cassel JB, et al. Cost savings associated with US hospital palliative care consultation programs. Arch Int Med. 2008;168(16):1783-1790.

- Institute of Medicine. Dying in America: Improving Quality and Honoring Individual Preferences near the End of Life. 2014.

- BPCI Model 2: Retrospective acute & post acute care episode. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services website. Accessed June 24, 2016.

- Vick JB, Pertsch N, Hutchings M, et al. The utility of the surprise question in identifying patients most at risk of death. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(suppl):8.

- Moss AH, Ganjoo J, Sharma S, et al. Utility of the “surprise” question to identify dialysis patients with high mortality. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;3:1379-1384.

- Moss AH, Lunney JR, Culp S, et al. Prognostic significance of the “surprise” question in cancer patients. J Palliat Med. 2010;13(7):837-840.

- Weissman D, Meier C. Identifying patients in need of a palliative care assessment in the hospital setting: a consensus report from the Center to Advance Palliative Care. J Palliat Med. 2011;14(1):17-23.

- Serious illness care resources. Ariadne Labs website. Accessed June 24, 2016.

Although effective palliative care has always been a must-have for patients and caregivers facing serious illness, it hasn’t always been readily available. With the emergence of value-based healthcare models—and their potent incentives to reduce avoidable readmissions—there is renewed hope that such care will be accessible to those who need it.

Palliative and end-of-life care have long been promoted as core skills for hospitalists. The topic has regularly been included at SHM annual meetings and other prominent hospital medicine conferences, in the American Board of Internal Medicine blueprint for recognition of focused practice in hospital medicine, and in a number of influential references for hospitalists. Still, as I look at hospitalist programs around the country, there is a clear need to improve hospitalists’ delivery of palliative and end-of-life care.

Care of patients with chronic illness in their last two years of life accounts for a third of all Medicare spending.1 As hospitalists, we encounter many of these patients as they are hospitalized—and often re-hospitalized. Palliative care, which can improve quality of life and decrease costs for patients while leading to increased satisfaction and better outcomes for caregivers, can help alleviate unneeded and unwanted aggressive interventions like hospitalization.2,3

In its 2014 report, Dying in America, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) identified several areas for improvement, including better advance care planning and payment systems supporting high quality end-of-life care.4 As I write this column in mid 2016, there are two notable achievements since the IOM report: two E&M codes for advance care planning and a substantial and growing number of hospitalist patients in alternative payment models like bundled payments or ACOs.5 I believe we are entering a time when the availability of good palliative care will be accelerated due to broader forces in healthcare that for the first time align incentives between patients’ wishes and how care is paid for.

Palliative Care Skills for Hospitalists

The following are key actions for physicians in addressing palliative care for the hospitalized patient. At the risk of oversimplifying the discipline, I offer a few key actions for hospitalists to keep in mind.

Identify patients who would benefit from palliative care. The surprise question—“Would I be surprised if this patient died in the next year?”—has the ability to predict which patients would benefit from palliative care. In one observation from a group of patients with cancer, a “no” answer identified 60% of patients who died within a year.6 The surprise question has previously been shown to be predictive in other cancer and non-cancer populations.7,8

Weisman and Meier suggest using the following in a checklist at the time of hospital admission as “primary criteria to screen for unmet palliative care needs”:9

- The surprise question

- Frequent admissions

- Admission prompted by difficult-to-control physical or psychological symptoms

- Complex care requirements

- Decline in function, feeding intolerance, or unintended decline in weight

Hold a “goals of care” meeting. A notable step forward for supporting conversations between physicians and patients occurred on Jan. 1, when the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) announced the Advance Care Planning E&M codes. These are CPT codes 99497 and 99498. They can be used on the same day as other E&M codes and cover discussions regarding advance care planning issues including discussing advance directives, appointing a healthcare proxy or durable power of attorney, discussing a living will, or addressing orders for life-sustaining treatment like the role of hydration or future hospitalizations. (For more information on how to use them, visit the CMS website and search for the FAQ.)

What should hospitalists concentrate on when having “goals of care” conversations with patients and caregivers? Ariadne Labs, a Harvard-affiliated health innovation group, offers the following as elements of a serious illness conversation:10

- Patients’ understanding of their illness

- Patients’ preferences for information and for family involvement

- Personal life goals, fears, and anxieties

- Trade-offs they are willing to accept

For hospitalists, an important area to pay particular attention to is the role of future hospitalizations in patients’ wishes for care, as some patients, if offered appropriate symptom control, would prefer to remain at home.

Two other crucial elements of inpatient palliative care—offer psychosocial support and symptom relief and hand off patient to effective post-hospital palliative care—are outside the scope of this article. However, they should be kept in mind and, of course, applied.

Understand the role of the palliative care consultation. Busy hospitalists might reasonably think, “I simply don’t have time to address palliative care in patients who aren’t likely to die during this hospitalization or soon after.” The palliative care consult service, if available, should be accessed when patients are identified as palliative care candidates but the primary hospitalist does not have the time or resources—including specialized knowledge in some cases—to deliver adequate palliative care. Palliative care specialists can also help bridge the gap between inpatient and outpatient palliative care resources.

In sum, the move to value-based payment models and the new advance care planning E&M codes provide a renewed focus—with more aligned incentives—and the opportunity to provide good palliative care to all who need it.

For hospitalists, identifying those who would benefit from palliative care and working with the healthcare team to ensure the care is delivered are at the heart of our professional mission. TH

References

- End-of-life care. The Darmouth Atlas of Health Care website. Accessed June 23, 2016.

- Gade G, Venohr I, Conner D, et al. Impact of an inpatient palliative care team: a randomized control trial. J Palliat Med. 2008;11(2):180-190.

- Morrison RS, Penrod JD, Cassel JB, et al. Cost savings associated with US hospital palliative care consultation programs. Arch Int Med. 2008;168(16):1783-1790.

- Institute of Medicine. Dying in America: Improving Quality and Honoring Individual Preferences near the End of Life. 2014.

- BPCI Model 2: Retrospective acute & post acute care episode. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services website. Accessed June 24, 2016.

- Vick JB, Pertsch N, Hutchings M, et al. The utility of the surprise question in identifying patients most at risk of death. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(suppl):8.

- Moss AH, Ganjoo J, Sharma S, et al. Utility of the “surprise” question to identify dialysis patients with high mortality. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;3:1379-1384.

- Moss AH, Lunney JR, Culp S, et al. Prognostic significance of the “surprise” question in cancer patients. J Palliat Med. 2010;13(7):837-840.

- Weissman D, Meier C. Identifying patients in need of a palliative care assessment in the hospital setting: a consensus report from the Center to Advance Palliative Care. J Palliat Med. 2011;14(1):17-23.

- Serious illness care resources. Ariadne Labs website. Accessed June 24, 2016.

8 Lessons for Hospitalists Turned Entrepreneurs

If you are a hospitalist, you are an entrepreneur almost by definition. All hospitalists are continuously engaged in improving the hospital experience for our patients. For some of us, the inner entrepreneur may grow to a point where we seriously consider a part-time or full-time commitment to an entrepreneurial dream. Combining our years of immersion in hospital patient care with an inventive streak can be a potent recipe for an innovative product or service idea.

It may be that the burgeoning startup scene in healthcare has inspired your dream. From coast to coast, there are startup incubators such as Rock Health, Healthbox, Blueprint Health, StartUp Health, Health Wildcatters, The Iron Yard, and TechSpring. These outfits support entrepreneurs with mentorship, funding, workspace, and/or information, such as how to deal with HIPAA or the FDA. Most of us have had at least a passing fascination with Steve Jobs–type characters, individuals who changed the world through their vision and force of will or who just seemed to enjoy a freedom that those who work for “The Man” will never know.

A few years ago, I caught the entrepreneurial bug. Initially, I continued with my day job and worked nights and weekends on my side project. Eventually, I made the leap to work full-time at an early-stage healthcare company. Since then, I’ve spent a lot of time trying to improve my new practice as a full-time entrepreneur, working as hard as ever, trying to be an effective innovator. Every day seems to bring new lessons—some more hard-earned than others—and there’s a lifetime of them still ahead. I’d like to share some of the insights I have learned on this journey. By the way, I still make time for patient care since that remains a priority for me.

Patience Is a Virtue, but Persistence and Positivity Count Even More

As Henry David Thoreau wrote, “Go confidently in the direction of your dreams.” Don’t postpone action indefinitely just because there are obstacles. Stop making excuses, make a start, and build momentum every day. Commit.

Becoming an entrepreneur is a long-term effort fueled by dedication and optimism, but first you have to make a start. You can’t win if you don’t play.

Action and Learning Matter More than Ideation

Start with your idea and a rough plan, but above all, believe in yourself, especially your ability to problem-solve. Many of the qualities that have fueled our success as physicians—precision, thoughtfulness, error aversion, and compulsiveness—might be constraints in a startup environment. Startups are hostile places for perfectionists and those who require complete information before proceeding. Have a bias for action and become comfortable with ambiguity. Entrepreneurs turn little things into big things by making progress every day.

Perhaps contrary to what we learn as physicians, entrepreneurs understand progress is measured more by authentic learning than by getting particular results. Entrepreneurs must quickly learn how to fail. In fact, progress often resembles multiple experiments that allow you to fail (and learn) faster. For entrepreneurs, perfection truly is the enemy of the good.

Learn, make adjustments, and progress will follow.

Guidance Is More Valuable than Money

Commercializing an idea is a challenging proposition. First-timers need advice, support, and help. For advice, find a mentor who has successfully launched a startup. Most of the successful people I know have had the wisdom or good fortune to have a mentor to provide guidance.

Startup incubators can be another source of support. Nearly all large cities and many medium and small cities now have business incubators or accelerators. Attend an event and get involved. They will provide many of the tools you will need to get started.

There are lots of opportunities for innovation in healthcare. But commercializing an idea will be one of the most challenging things you’ll ever do. Surround yourself with people who have skills that complement yours. Physician entrepreneurs need to be part of a viable team.

Sell, Sell, Sell

In business, as in life, “we’re all in sales.” We sell our ideas, our work product, ourselves. Even as physicians we have to sell patients and colleagues on our thought processes to be successful. Successful entrepreneurs are comfortable selling and put their best foot forward when trying to recruit a resource or persuade a potential customer.

Conflicts of Interest

“There is no interest without conflict.” If you look hard enough, you’ll see that we all have conflicts of interest. The key is to recognize them and disclose them. Of course, there are certain conflicts that are deal breakers. They must be avoided. If you remain employed, most of them are spelled out in your employer’s conflict of interest and intellectual property policies.

HIPAA Is an Innovation Killer

If your idea involves technology or services that address protected health information, become a HIPAA savant as soon as possible. The good news is that if you can effectively navigate the HIPAA challenge, you will have an advantage over your competitors.

Pure ‘Tech’ Plays Are Difficult

If you want to try to build the next killer app for healthcare and hope it will go viral, good luck. Based on my experience, it is difficult to get market traction with a pure technology offering. The strategy with a higher likelihood of success is to provide services with a technology platform that supports those services. As a provider of a service, you can provide immediate value to the customer and become “sticky” as you build your business (and software).

Enjoy the Journey, No Matter What

At first, you will be propelled by irrational exuberance and a passion for the greatness of your idea. That’s not only a good thing, it’s a requirement. But becoming a successful entrepreneur is a heavy haul down a long road of hard work and execution. Enjoying the journey is crucial since, beyond that, there are no guarantees. But life is short, so maybe you also value a career with no regrets. Take a chance and enjoy the ride.

Being a physician entrepreneur is not for everyone. But for those who take the plunge, it can be one of the most fulfilling, exciting, and meaningful journeys one could imagine. TH

Author note: I’d like to thank Dr. Jason Stein and Joe Miller for their helpful comments on this column.

If you are a hospitalist, you are an entrepreneur almost by definition. All hospitalists are continuously engaged in improving the hospital experience for our patients. For some of us, the inner entrepreneur may grow to a point where we seriously consider a part-time or full-time commitment to an entrepreneurial dream. Combining our years of immersion in hospital patient care with an inventive streak can be a potent recipe for an innovative product or service idea.

It may be that the burgeoning startup scene in healthcare has inspired your dream. From coast to coast, there are startup incubators such as Rock Health, Healthbox, Blueprint Health, StartUp Health, Health Wildcatters, The Iron Yard, and TechSpring. These outfits support entrepreneurs with mentorship, funding, workspace, and/or information, such as how to deal with HIPAA or the FDA. Most of us have had at least a passing fascination with Steve Jobs–type characters, individuals who changed the world through their vision and force of will or who just seemed to enjoy a freedom that those who work for “The Man” will never know.

A few years ago, I caught the entrepreneurial bug. Initially, I continued with my day job and worked nights and weekends on my side project. Eventually, I made the leap to work full-time at an early-stage healthcare company. Since then, I’ve spent a lot of time trying to improve my new practice as a full-time entrepreneur, working as hard as ever, trying to be an effective innovator. Every day seems to bring new lessons—some more hard-earned than others—and there’s a lifetime of them still ahead. I’d like to share some of the insights I have learned on this journey. By the way, I still make time for patient care since that remains a priority for me.

Patience Is a Virtue, but Persistence and Positivity Count Even More

As Henry David Thoreau wrote, “Go confidently in the direction of your dreams.” Don’t postpone action indefinitely just because there are obstacles. Stop making excuses, make a start, and build momentum every day. Commit.

Becoming an entrepreneur is a long-term effort fueled by dedication and optimism, but first you have to make a start. You can’t win if you don’t play.

Action and Learning Matter More than Ideation

Start with your idea and a rough plan, but above all, believe in yourself, especially your ability to problem-solve. Many of the qualities that have fueled our success as physicians—precision, thoughtfulness, error aversion, and compulsiveness—might be constraints in a startup environment. Startups are hostile places for perfectionists and those who require complete information before proceeding. Have a bias for action and become comfortable with ambiguity. Entrepreneurs turn little things into big things by making progress every day.

Perhaps contrary to what we learn as physicians, entrepreneurs understand progress is measured more by authentic learning than by getting particular results. Entrepreneurs must quickly learn how to fail. In fact, progress often resembles multiple experiments that allow you to fail (and learn) faster. For entrepreneurs, perfection truly is the enemy of the good.

Learn, make adjustments, and progress will follow.

Guidance Is More Valuable than Money

Commercializing an idea is a challenging proposition. First-timers need advice, support, and help. For advice, find a mentor who has successfully launched a startup. Most of the successful people I know have had the wisdom or good fortune to have a mentor to provide guidance.

Startup incubators can be another source of support. Nearly all large cities and many medium and small cities now have business incubators or accelerators. Attend an event and get involved. They will provide many of the tools you will need to get started.

There are lots of opportunities for innovation in healthcare. But commercializing an idea will be one of the most challenging things you’ll ever do. Surround yourself with people who have skills that complement yours. Physician entrepreneurs need to be part of a viable team.

Sell, Sell, Sell

In business, as in life, “we’re all in sales.” We sell our ideas, our work product, ourselves. Even as physicians we have to sell patients and colleagues on our thought processes to be successful. Successful entrepreneurs are comfortable selling and put their best foot forward when trying to recruit a resource or persuade a potential customer.

Conflicts of Interest

“There is no interest without conflict.” If you look hard enough, you’ll see that we all have conflicts of interest. The key is to recognize them and disclose them. Of course, there are certain conflicts that are deal breakers. They must be avoided. If you remain employed, most of them are spelled out in your employer’s conflict of interest and intellectual property policies.

HIPAA Is an Innovation Killer

If your idea involves technology or services that address protected health information, become a HIPAA savant as soon as possible. The good news is that if you can effectively navigate the HIPAA challenge, you will have an advantage over your competitors.

Pure ‘Tech’ Plays Are Difficult

If you want to try to build the next killer app for healthcare and hope it will go viral, good luck. Based on my experience, it is difficult to get market traction with a pure technology offering. The strategy with a higher likelihood of success is to provide services with a technology platform that supports those services. As a provider of a service, you can provide immediate value to the customer and become “sticky” as you build your business (and software).

Enjoy the Journey, No Matter What

At first, you will be propelled by irrational exuberance and a passion for the greatness of your idea. That’s not only a good thing, it’s a requirement. But becoming a successful entrepreneur is a heavy haul down a long road of hard work and execution. Enjoying the journey is crucial since, beyond that, there are no guarantees. But life is short, so maybe you also value a career with no regrets. Take a chance and enjoy the ride.

Being a physician entrepreneur is not for everyone. But for those who take the plunge, it can be one of the most fulfilling, exciting, and meaningful journeys one could imagine. TH

Author note: I’d like to thank Dr. Jason Stein and Joe Miller for their helpful comments on this column.

If you are a hospitalist, you are an entrepreneur almost by definition. All hospitalists are continuously engaged in improving the hospital experience for our patients. For some of us, the inner entrepreneur may grow to a point where we seriously consider a part-time or full-time commitment to an entrepreneurial dream. Combining our years of immersion in hospital patient care with an inventive streak can be a potent recipe for an innovative product or service idea.

It may be that the burgeoning startup scene in healthcare has inspired your dream. From coast to coast, there are startup incubators such as Rock Health, Healthbox, Blueprint Health, StartUp Health, Health Wildcatters, The Iron Yard, and TechSpring. These outfits support entrepreneurs with mentorship, funding, workspace, and/or information, such as how to deal with HIPAA or the FDA. Most of us have had at least a passing fascination with Steve Jobs–type characters, individuals who changed the world through their vision and force of will or who just seemed to enjoy a freedom that those who work for “The Man” will never know.

A few years ago, I caught the entrepreneurial bug. Initially, I continued with my day job and worked nights and weekends on my side project. Eventually, I made the leap to work full-time at an early-stage healthcare company. Since then, I’ve spent a lot of time trying to improve my new practice as a full-time entrepreneur, working as hard as ever, trying to be an effective innovator. Every day seems to bring new lessons—some more hard-earned than others—and there’s a lifetime of them still ahead. I’d like to share some of the insights I have learned on this journey. By the way, I still make time for patient care since that remains a priority for me.

Patience Is a Virtue, but Persistence and Positivity Count Even More

As Henry David Thoreau wrote, “Go confidently in the direction of your dreams.” Don’t postpone action indefinitely just because there are obstacles. Stop making excuses, make a start, and build momentum every day. Commit.

Becoming an entrepreneur is a long-term effort fueled by dedication and optimism, but first you have to make a start. You can’t win if you don’t play.

Action and Learning Matter More than Ideation

Start with your idea and a rough plan, but above all, believe in yourself, especially your ability to problem-solve. Many of the qualities that have fueled our success as physicians—precision, thoughtfulness, error aversion, and compulsiveness—might be constraints in a startup environment. Startups are hostile places for perfectionists and those who require complete information before proceeding. Have a bias for action and become comfortable with ambiguity. Entrepreneurs turn little things into big things by making progress every day.

Perhaps contrary to what we learn as physicians, entrepreneurs understand progress is measured more by authentic learning than by getting particular results. Entrepreneurs must quickly learn how to fail. In fact, progress often resembles multiple experiments that allow you to fail (and learn) faster. For entrepreneurs, perfection truly is the enemy of the good.

Learn, make adjustments, and progress will follow.

Guidance Is More Valuable than Money

Commercializing an idea is a challenging proposition. First-timers need advice, support, and help. For advice, find a mentor who has successfully launched a startup. Most of the successful people I know have had the wisdom or good fortune to have a mentor to provide guidance.

Startup incubators can be another source of support. Nearly all large cities and many medium and small cities now have business incubators or accelerators. Attend an event and get involved. They will provide many of the tools you will need to get started.

There are lots of opportunities for innovation in healthcare. But commercializing an idea will be one of the most challenging things you’ll ever do. Surround yourself with people who have skills that complement yours. Physician entrepreneurs need to be part of a viable team.

Sell, Sell, Sell

In business, as in life, “we’re all in sales.” We sell our ideas, our work product, ourselves. Even as physicians we have to sell patients and colleagues on our thought processes to be successful. Successful entrepreneurs are comfortable selling and put their best foot forward when trying to recruit a resource or persuade a potential customer.

Conflicts of Interest

“There is no interest without conflict.” If you look hard enough, you’ll see that we all have conflicts of interest. The key is to recognize them and disclose them. Of course, there are certain conflicts that are deal breakers. They must be avoided. If you remain employed, most of them are spelled out in your employer’s conflict of interest and intellectual property policies.

HIPAA Is an Innovation Killer

If your idea involves technology or services that address protected health information, become a HIPAA savant as soon as possible. The good news is that if you can effectively navigate the HIPAA challenge, you will have an advantage over your competitors.

Pure ‘Tech’ Plays Are Difficult

If you want to try to build the next killer app for healthcare and hope it will go viral, good luck. Based on my experience, it is difficult to get market traction with a pure technology offering. The strategy with a higher likelihood of success is to provide services with a technology platform that supports those services. As a provider of a service, you can provide immediate value to the customer and become “sticky” as you build your business (and software).

Enjoy the Journey, No Matter What

At first, you will be propelled by irrational exuberance and a passion for the greatness of your idea. That’s not only a good thing, it’s a requirement. But becoming a successful entrepreneur is a heavy haul down a long road of hard work and execution. Enjoying the journey is crucial since, beyond that, there are no guarantees. But life is short, so maybe you also value a career with no regrets. Take a chance and enjoy the ride.

Being a physician entrepreneur is not for everyone. But for those who take the plunge, it can be one of the most fulfilling, exciting, and meaningful journeys one could imagine. TH

Author note: I’d like to thank Dr. Jason Stein and Joe Miller for their helpful comments on this column.

Revisiting the ‘Key Principles and Characteristics of an Effective Hospital Medicine Group'

It has been two years since the “Key Characteristics” was published in the Journal of Hospital Medicine.1 The SHM board of directors envisions the Key Characteristics as a tool to improve the performance of hospital medicine groups (HMGs) and “raise the bar” for the specialty.

At SHM’s annual meeting (www.hospitalmedicine2016.org) next month in San Diego, the Key Characteristics will provide the framework for the Practice Management Pre-Course (Sunday, March 6). The pre-course faculty, of which I am a member, will address all 10 principles of the Key Characteristics (see Table 1), including case studies and practical ideas for performance improvement. As a preview, I will cover Principle 6 and provide a few practical tips that you can implement in your practice.

For a more comprehensive discussion of all the Key Characteristics and how to use them, visit the SHM website (visit www.hospitalmedicine.org, then click on the “Practice Management” icon at the top of the landing page).

Characteristic 6.1

The HMG has systems in place to ensure effective and reliable communication with the patient’s primary care physician and/or other provider(s) involved in the patient’s care in the non-acute-care setting.

Practical tip: Your practice probably has administrative procedures in place to notify PCPs that their patient has been admitted to the hospital, using the electronic health record or secure email, if available, or messaging by fax/phone. But are you receiving vital information from the PCP’s office or from the nursing facility? Establish a protocol for obtaining key history, medication, and diagnostic testing information from these sources. One approach is to request this information when notifying the PCP of the patient’s admission.

Practical tip: Use the “grocery store test” to determine when to contact the PCP during the hospital stay. For example, if the PCP were to run into a family member of the patient in the grocery store, would the PCP want to have learned of a change in the patient’s condition in advance of the family member encounter?

Practical tip: Because reaching skilling nursing facility (SNF) physicians/providers (SNFists) can be challenging, hold an annual social event so that they can meet the hospitalists in your practice face-to-face. At the event, exchange cellphone or beeper numbers with the SNFists, and establish an explicit understanding of how handoffs will occur, especially for high-risk patients.

Characteristic 6.2

The HMG contributes in meaningful ways to the hospital’s efforts to improve care transitions.

Because of readmissions penalties, every hospital in the country is concerned with care transitions and avoiding readmissions. But HMGs want to know which interventions reliably decrease readmissions. The Commonwealth Fund recently released the results of a study of 428 hospitals that participated in national efforts to reduce readmissions, including the State Action on Avoidable Rehospitalizations (STAAR) and Hospital to Home (H2H) initiatives. The study’s primary conclusions were as follows:

- The only strategy consistently associated with reduced risk-standardized readmissions was discharging patients with their appointments already made.2 No other single strategy was reliably associated with a reduction.

- Hospitals that implemented three or more readmission reduction strategies showed a significant decrease in risk-standardized readmissions versus those implementing fewer than three.

Practical tip: Ensure patients leave the hospital with a PCP follow-up appointment made and in hand.

Practical tip: Work with your hospital on at least three definitive strategies to reduce readmissions.

Implement to Improve Your HMG

The basic and updated 2015 versions of the “Key Principles and Characteristics of an Effective Hospital Medicine Group” can be downloaded from the SHM website (visit www.hospitalmedicine.org, then click on the “Practice Management” icon at the top of the landing page). The updated 2015 version provides definitions and requirements and suggested approaches to demonstrating the characteristic that enables the HMG to conduct a comprehensive self-assessment.

In addition, there is a new tool intended for use by hospitalist practice administrators that cross-references the Key Characteristics with another tool, The Core Competencies for a Hospitalist Practice Administrator. TH

References

- Cawley P, Deitelzweig S, Flores L, et al. The key principles and characteristics of an effective hospital medicine group: an assessment guide for hospitals and hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(2):123-128.

- Bradley EH, Brewster A, Curry L. National campaigns to reduce readmissions: what have we learned? The Commonwealth Fund website. Available at: commonwealthfund.org/publications/blog/2015/oct/national-campaigns-to-reduce-readmissions. Accessed December 28, 2015.

It has been two years since the “Key Characteristics” was published in the Journal of Hospital Medicine.1 The SHM board of directors envisions the Key Characteristics as a tool to improve the performance of hospital medicine groups (HMGs) and “raise the bar” for the specialty.

At SHM’s annual meeting (www.hospitalmedicine2016.org) next month in San Diego, the Key Characteristics will provide the framework for the Practice Management Pre-Course (Sunday, March 6). The pre-course faculty, of which I am a member, will address all 10 principles of the Key Characteristics (see Table 1), including case studies and practical ideas for performance improvement. As a preview, I will cover Principle 6 and provide a few practical tips that you can implement in your practice.

For a more comprehensive discussion of all the Key Characteristics and how to use them, visit the SHM website (visit www.hospitalmedicine.org, then click on the “Practice Management” icon at the top of the landing page).

Characteristic 6.1

The HMG has systems in place to ensure effective and reliable communication with the patient’s primary care physician and/or other provider(s) involved in the patient’s care in the non-acute-care setting.

Practical tip: Your practice probably has administrative procedures in place to notify PCPs that their patient has been admitted to the hospital, using the electronic health record or secure email, if available, or messaging by fax/phone. But are you receiving vital information from the PCP’s office or from the nursing facility? Establish a protocol for obtaining key history, medication, and diagnostic testing information from these sources. One approach is to request this information when notifying the PCP of the patient’s admission.

Practical tip: Use the “grocery store test” to determine when to contact the PCP during the hospital stay. For example, if the PCP were to run into a family member of the patient in the grocery store, would the PCP want to have learned of a change in the patient’s condition in advance of the family member encounter?

Practical tip: Because reaching skilling nursing facility (SNF) physicians/providers (SNFists) can be challenging, hold an annual social event so that they can meet the hospitalists in your practice face-to-face. At the event, exchange cellphone or beeper numbers with the SNFists, and establish an explicit understanding of how handoffs will occur, especially for high-risk patients.

Characteristic 6.2

The HMG contributes in meaningful ways to the hospital’s efforts to improve care transitions.

Because of readmissions penalties, every hospital in the country is concerned with care transitions and avoiding readmissions. But HMGs want to know which interventions reliably decrease readmissions. The Commonwealth Fund recently released the results of a study of 428 hospitals that participated in national efforts to reduce readmissions, including the State Action on Avoidable Rehospitalizations (STAAR) and Hospital to Home (H2H) initiatives. The study’s primary conclusions were as follows:

- The only strategy consistently associated with reduced risk-standardized readmissions was discharging patients with their appointments already made.2 No other single strategy was reliably associated with a reduction.

- Hospitals that implemented three or more readmission reduction strategies showed a significant decrease in risk-standardized readmissions versus those implementing fewer than three.

Practical tip: Ensure patients leave the hospital with a PCP follow-up appointment made and in hand.

Practical tip: Work with your hospital on at least three definitive strategies to reduce readmissions.

Implement to Improve Your HMG

The basic and updated 2015 versions of the “Key Principles and Characteristics of an Effective Hospital Medicine Group” can be downloaded from the SHM website (visit www.hospitalmedicine.org, then click on the “Practice Management” icon at the top of the landing page). The updated 2015 version provides definitions and requirements and suggested approaches to demonstrating the characteristic that enables the HMG to conduct a comprehensive self-assessment.

In addition, there is a new tool intended for use by hospitalist practice administrators that cross-references the Key Characteristics with another tool, The Core Competencies for a Hospitalist Practice Administrator. TH

References

- Cawley P, Deitelzweig S, Flores L, et al. The key principles and characteristics of an effective hospital medicine group: an assessment guide for hospitals and hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(2):123-128.

- Bradley EH, Brewster A, Curry L. National campaigns to reduce readmissions: what have we learned? The Commonwealth Fund website. Available at: commonwealthfund.org/publications/blog/2015/oct/national-campaigns-to-reduce-readmissions. Accessed December 28, 2015.

It has been two years since the “Key Characteristics” was published in the Journal of Hospital Medicine.1 The SHM board of directors envisions the Key Characteristics as a tool to improve the performance of hospital medicine groups (HMGs) and “raise the bar” for the specialty.

At SHM’s annual meeting (www.hospitalmedicine2016.org) next month in San Diego, the Key Characteristics will provide the framework for the Practice Management Pre-Course (Sunday, March 6). The pre-course faculty, of which I am a member, will address all 10 principles of the Key Characteristics (see Table 1), including case studies and practical ideas for performance improvement. As a preview, I will cover Principle 6 and provide a few practical tips that you can implement in your practice.

For a more comprehensive discussion of all the Key Characteristics and how to use them, visit the SHM website (visit www.hospitalmedicine.org, then click on the “Practice Management” icon at the top of the landing page).

Characteristic 6.1

The HMG has systems in place to ensure effective and reliable communication with the patient’s primary care physician and/or other provider(s) involved in the patient’s care in the non-acute-care setting.

Practical tip: Your practice probably has administrative procedures in place to notify PCPs that their patient has been admitted to the hospital, using the electronic health record or secure email, if available, or messaging by fax/phone. But are you receiving vital information from the PCP’s office or from the nursing facility? Establish a protocol for obtaining key history, medication, and diagnostic testing information from these sources. One approach is to request this information when notifying the PCP of the patient’s admission.

Practical tip: Use the “grocery store test” to determine when to contact the PCP during the hospital stay. For example, if the PCP were to run into a family member of the patient in the grocery store, would the PCP want to have learned of a change in the patient’s condition in advance of the family member encounter?

Practical tip: Because reaching skilling nursing facility (SNF) physicians/providers (SNFists) can be challenging, hold an annual social event so that they can meet the hospitalists in your practice face-to-face. At the event, exchange cellphone or beeper numbers with the SNFists, and establish an explicit understanding of how handoffs will occur, especially for high-risk patients.

Characteristic 6.2

The HMG contributes in meaningful ways to the hospital’s efforts to improve care transitions.

Because of readmissions penalties, every hospital in the country is concerned with care transitions and avoiding readmissions. But HMGs want to know which interventions reliably decrease readmissions. The Commonwealth Fund recently released the results of a study of 428 hospitals that participated in national efforts to reduce readmissions, including the State Action on Avoidable Rehospitalizations (STAAR) and Hospital to Home (H2H) initiatives. The study’s primary conclusions were as follows:

- The only strategy consistently associated with reduced risk-standardized readmissions was discharging patients with their appointments already made.2 No other single strategy was reliably associated with a reduction.

- Hospitals that implemented three or more readmission reduction strategies showed a significant decrease in risk-standardized readmissions versus those implementing fewer than three.

Practical tip: Ensure patients leave the hospital with a PCP follow-up appointment made and in hand.

Practical tip: Work with your hospital on at least three definitive strategies to reduce readmissions.

Implement to Improve Your HMG

The basic and updated 2015 versions of the “Key Principles and Characteristics of an Effective Hospital Medicine Group” can be downloaded from the SHM website (visit www.hospitalmedicine.org, then click on the “Practice Management” icon at the top of the landing page). The updated 2015 version provides definitions and requirements and suggested approaches to demonstrating the characteristic that enables the HMG to conduct a comprehensive self-assessment.