User login

Dr. Whitcomb is chief medical officer of Remedy Partners. He is co-founder and past president of SHM. E-mail him at wfwhit@comcast.net.

Much Ado about Hospital Quality

I have reported previously on major incentive programs under Medicare and the Affordable Care Act that affect hospitals and, by extension, their affiliated hospitalists. I’d like to provide you with an update on these programs. The bad news is that hospitals have more revenue than ever that is at risk based on performance. The good news is that such risk, and its mitigation, centers on performance measures in the sweet spot of hospitalists and the teams they work with to improve patient care.

Hospital-Acquired Conditions

On Dec. 17, 2014, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) announced that 724 U.S. hospitals—the lowest quartile—will have 1% of their reimbursement docked effective Oct. 1, 2014, as part of the Hospital-Acquired Condition Reduction Program (HACRP). The HACRP is divided into the following domains:

- 35%, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Patient Safety Indicators (PSI-90). This is a composite of eight claims-based harm measures.

- 65%, CDC National Health Safety Network measures. These are clinically derived metrics, currently central line-associated blood stream infection (CLABSI) and catheter-associated urinary tract infection (CAUTI).

The HACRP program, which debuted in October 2014, will continue at least through 2020. The 65% weight domain will change in FY16 with the addition of surgical site infections (colon, hysterectomy) and in FY17 with the addition of MRSA and Clostridium difficile infections.

The full list of U.S. hospitals and their performance in the HACRP and the Hospital Value-Based Purchasing (VBP) program is available at www.modernhealthcare.com/article/20141108/INFO/141109959.

Just two weeks prior to the CMS announcement, AHRQ announced some major accomplishments in efforts to address patient safety at U.S. hospitals. The agency reported that the number of hospital-acquired conditions in the Partnership for Patients (PfP) program in the U.S. declined 9% over a one-year period (2012 to 2013) and 17% over a three-year period (2010 to 2013). Hospital-acquired conditions are defined somewhat differently in the PfP than in the HACRP, with PfP targeting certain hospital-acquired infections, pressure ulcers, falls, and adverse drug effects.

The report noted that reductions in adverse drug events and pressure ulcers were the largest contributors to a reported 50,000 fewer in-hospital deaths over the 2010-2013 period.

Hospital Value-Based Purchasing

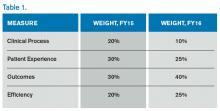

The Hospital VBP program continues to evolve. See Table 1 for a breakdown of the program for the next two years.

Unlike the HACRP and the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program, which are pure penalty programs, VBP has hospitals at risk for 1.5% (for 2015) of Medicare payments, but they may earn back some, all, or an amount in excess of the 1.5% based on performance. For the years noted above, the VBP program metrics are as follows:

- Clinical Process: selected heart failure (HF), pneumonia (PN), myocardial infarction (MI), and surgical care measures.

- Patient Experience: a subset of the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) survey questions.

- Outcomes: HF, PN, MI, 30-day mortality, CLABSI, and PSI-90.

- Efficiency: Medicare spending per beneficiary (spending from three days prior to an inpatient hospital admission through 30 days after discharge)

Readmission Penalties

CMS announced that in the latest round of the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program, 2,610 hospitals were penalized in total, while 39 hospitals will receive the largest penalty allowed. For FY15, the program added chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and hip and knee arthroplasty to HF, PN, and MI as the conditions counting toward excess readmissions.

For FY15, the number of hospitals penalized and the amount of the penalty are expected to increase. In addition, 1% of hospitals are anticipated to receive the maximum penalty, while 77% are expected to have some penalty, and 22% will likely have no penalty. The maximum penalty has topped out at 3% of Medicare inpatient payments.

HCAHPS Star Ratings

The CMS Hospital Compare website will debut ‘star ratings’ in April 2015 to make it easier for consumers to decipher the site’s information. In a format similar to the one used by Nursing Home Compare, the website will use a five-star rating system based on the 11 publicly reported HCAHPS measures. The initial ratings will be based on discharges during the period ranging from July 2013 through June 2014.

What’s a Hospitalist to Do?

The latest version of CMS incentive programs should serve to reinforce your hospital medicine group’s strategy to be agents of collaboration and change. Link up with your quality department to align priorities, and make sure you have hospitalist representatives on key patient safety, patient experience, and quality improvement committees.

Because dollars are at stake for your hospital, have a clear understanding of the value your hospitalist group brings to the table, so you can secure the appropriate financial support for the time and work expended on these initiatives.

And don’t forget to keep the patient at the center of your efforts.

I have reported previously on major incentive programs under Medicare and the Affordable Care Act that affect hospitals and, by extension, their affiliated hospitalists. I’d like to provide you with an update on these programs. The bad news is that hospitals have more revenue than ever that is at risk based on performance. The good news is that such risk, and its mitigation, centers on performance measures in the sweet spot of hospitalists and the teams they work with to improve patient care.

Hospital-Acquired Conditions

On Dec. 17, 2014, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) announced that 724 U.S. hospitals—the lowest quartile—will have 1% of their reimbursement docked effective Oct. 1, 2014, as part of the Hospital-Acquired Condition Reduction Program (HACRP). The HACRP is divided into the following domains:

- 35%, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Patient Safety Indicators (PSI-90). This is a composite of eight claims-based harm measures.

- 65%, CDC National Health Safety Network measures. These are clinically derived metrics, currently central line-associated blood stream infection (CLABSI) and catheter-associated urinary tract infection (CAUTI).

The HACRP program, which debuted in October 2014, will continue at least through 2020. The 65% weight domain will change in FY16 with the addition of surgical site infections (colon, hysterectomy) and in FY17 with the addition of MRSA and Clostridium difficile infections.

The full list of U.S. hospitals and their performance in the HACRP and the Hospital Value-Based Purchasing (VBP) program is available at www.modernhealthcare.com/article/20141108/INFO/141109959.

Just two weeks prior to the CMS announcement, AHRQ announced some major accomplishments in efforts to address patient safety at U.S. hospitals. The agency reported that the number of hospital-acquired conditions in the Partnership for Patients (PfP) program in the U.S. declined 9% over a one-year period (2012 to 2013) and 17% over a three-year period (2010 to 2013). Hospital-acquired conditions are defined somewhat differently in the PfP than in the HACRP, with PfP targeting certain hospital-acquired infections, pressure ulcers, falls, and adverse drug effects.

The report noted that reductions in adverse drug events and pressure ulcers were the largest contributors to a reported 50,000 fewer in-hospital deaths over the 2010-2013 period.

Hospital Value-Based Purchasing

The Hospital VBP program continues to evolve. See Table 1 for a breakdown of the program for the next two years.

Unlike the HACRP and the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program, which are pure penalty programs, VBP has hospitals at risk for 1.5% (for 2015) of Medicare payments, but they may earn back some, all, or an amount in excess of the 1.5% based on performance. For the years noted above, the VBP program metrics are as follows:

- Clinical Process: selected heart failure (HF), pneumonia (PN), myocardial infarction (MI), and surgical care measures.

- Patient Experience: a subset of the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) survey questions.

- Outcomes: HF, PN, MI, 30-day mortality, CLABSI, and PSI-90.

- Efficiency: Medicare spending per beneficiary (spending from three days prior to an inpatient hospital admission through 30 days after discharge)

Readmission Penalties

CMS announced that in the latest round of the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program, 2,610 hospitals were penalized in total, while 39 hospitals will receive the largest penalty allowed. For FY15, the program added chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and hip and knee arthroplasty to HF, PN, and MI as the conditions counting toward excess readmissions.

For FY15, the number of hospitals penalized and the amount of the penalty are expected to increase. In addition, 1% of hospitals are anticipated to receive the maximum penalty, while 77% are expected to have some penalty, and 22% will likely have no penalty. The maximum penalty has topped out at 3% of Medicare inpatient payments.

HCAHPS Star Ratings

The CMS Hospital Compare website will debut ‘star ratings’ in April 2015 to make it easier for consumers to decipher the site’s information. In a format similar to the one used by Nursing Home Compare, the website will use a five-star rating system based on the 11 publicly reported HCAHPS measures. The initial ratings will be based on discharges during the period ranging from July 2013 through June 2014.

What’s a Hospitalist to Do?

The latest version of CMS incentive programs should serve to reinforce your hospital medicine group’s strategy to be agents of collaboration and change. Link up with your quality department to align priorities, and make sure you have hospitalist representatives on key patient safety, patient experience, and quality improvement committees.

Because dollars are at stake for your hospital, have a clear understanding of the value your hospitalist group brings to the table, so you can secure the appropriate financial support for the time and work expended on these initiatives.

And don’t forget to keep the patient at the center of your efforts.

I have reported previously on major incentive programs under Medicare and the Affordable Care Act that affect hospitals and, by extension, their affiliated hospitalists. I’d like to provide you with an update on these programs. The bad news is that hospitals have more revenue than ever that is at risk based on performance. The good news is that such risk, and its mitigation, centers on performance measures in the sweet spot of hospitalists and the teams they work with to improve patient care.

Hospital-Acquired Conditions

On Dec. 17, 2014, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) announced that 724 U.S. hospitals—the lowest quartile—will have 1% of their reimbursement docked effective Oct. 1, 2014, as part of the Hospital-Acquired Condition Reduction Program (HACRP). The HACRP is divided into the following domains:

- 35%, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Patient Safety Indicators (PSI-90). This is a composite of eight claims-based harm measures.

- 65%, CDC National Health Safety Network measures. These are clinically derived metrics, currently central line-associated blood stream infection (CLABSI) and catheter-associated urinary tract infection (CAUTI).

The HACRP program, which debuted in October 2014, will continue at least through 2020. The 65% weight domain will change in FY16 with the addition of surgical site infections (colon, hysterectomy) and in FY17 with the addition of MRSA and Clostridium difficile infections.

The full list of U.S. hospitals and their performance in the HACRP and the Hospital Value-Based Purchasing (VBP) program is available at www.modernhealthcare.com/article/20141108/INFO/141109959.

Just two weeks prior to the CMS announcement, AHRQ announced some major accomplishments in efforts to address patient safety at U.S. hospitals. The agency reported that the number of hospital-acquired conditions in the Partnership for Patients (PfP) program in the U.S. declined 9% over a one-year period (2012 to 2013) and 17% over a three-year period (2010 to 2013). Hospital-acquired conditions are defined somewhat differently in the PfP than in the HACRP, with PfP targeting certain hospital-acquired infections, pressure ulcers, falls, and adverse drug effects.

The report noted that reductions in adverse drug events and pressure ulcers were the largest contributors to a reported 50,000 fewer in-hospital deaths over the 2010-2013 period.

Hospital Value-Based Purchasing

The Hospital VBP program continues to evolve. See Table 1 for a breakdown of the program for the next two years.

Unlike the HACRP and the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program, which are pure penalty programs, VBP has hospitals at risk for 1.5% (for 2015) of Medicare payments, but they may earn back some, all, or an amount in excess of the 1.5% based on performance. For the years noted above, the VBP program metrics are as follows:

- Clinical Process: selected heart failure (HF), pneumonia (PN), myocardial infarction (MI), and surgical care measures.

- Patient Experience: a subset of the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) survey questions.

- Outcomes: HF, PN, MI, 30-day mortality, CLABSI, and PSI-90.

- Efficiency: Medicare spending per beneficiary (spending from three days prior to an inpatient hospital admission through 30 days after discharge)

Readmission Penalties

CMS announced that in the latest round of the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program, 2,610 hospitals were penalized in total, while 39 hospitals will receive the largest penalty allowed. For FY15, the program added chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and hip and knee arthroplasty to HF, PN, and MI as the conditions counting toward excess readmissions.

For FY15, the number of hospitals penalized and the amount of the penalty are expected to increase. In addition, 1% of hospitals are anticipated to receive the maximum penalty, while 77% are expected to have some penalty, and 22% will likely have no penalty. The maximum penalty has topped out at 3% of Medicare inpatient payments.

HCAHPS Star Ratings

The CMS Hospital Compare website will debut ‘star ratings’ in April 2015 to make it easier for consumers to decipher the site’s information. In a format similar to the one used by Nursing Home Compare, the website will use a five-star rating system based on the 11 publicly reported HCAHPS measures. The initial ratings will be based on discharges during the period ranging from July 2013 through June 2014.

What’s a Hospitalist to Do?

The latest version of CMS incentive programs should serve to reinforce your hospital medicine group’s strategy to be agents of collaboration and change. Link up with your quality department to align priorities, and make sure you have hospitalist representatives on key patient safety, patient experience, and quality improvement committees.

Because dollars are at stake for your hospital, have a clear understanding of the value your hospitalist group brings to the table, so you can secure the appropriate financial support for the time and work expended on these initiatives.

And don’t forget to keep the patient at the center of your efforts.

A Practice Resolution

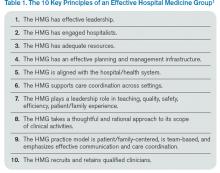

In the heart of the holiday season’s gluttony (and the challenges of staffing the holidays), we need something to get us excited for 2015. Let me suggest that you resolve to use “The Key Principles and Characteristics of an Effective Hospital Medicine Group: An Assessment Guide for Hospitals and Hospitalists” to trim those holiday pounds and make your hospitalist group (HMG) fitter than ever.1

When we published the “Key Principles and Characteristics” in the Journal of Hospital Medicine in February, we intended it to be “aspirational, helping to raise the bar for the specialty of hospital medicine.”1 The author group’s intent was to provide a framework for quality improvement at the HMG level. One can use the 10 principles and 47 characteristics as a basis for self-assessment within the cycle of quality improvement. I will provide an illustration of how a group might utilize the guide to improve its performance using an example and W. Edward Deming’s classic plan-do-study-act (PDSA) cycle.

Principle 6: The HMG supports care coordination across settings.

Characteristic 6.1: The HMG has systems in place to ensure effective and reliable communication with the patient’s primary care provider and/or other providers involved in the patient’s care in the nonacute care setting.

Plan

This phase involves identifying a goal, setting success metrics, and putting a plan into action.

Example: 90% of primary care providers (PCPs) will receive a discharge summary within 24 hours of discharge.

Do

Here the key components of the plan are implemented.

Example: All referring PCPs’ preferred methods of communication and contact information are documented. The HMG has the ability to utilize such communication, e.g. electronic health record (EHR) e-mail or electronic fax. All hospitalists prepare a discharge summary in real time.

Study

In this phase, outcomes are assessed for success and barriers.

Example: Although 97% of discharge summaries are transmitted according to the PCPs’ preferred communication, PCPs state that they received it only 78% of the time.

Act

This is where the lessons learned throughout the process are integrated to adjust the methods, the goal, or the approach in general. Then the entire cycle is repeated.

Example: Even though most PCPs are on the same EHR system as the hospitalists, they don’t check their EHR e-mail (even though during the Plan phase they said they did). Their office staff uses electronic fax, so that will be the method of communication for the PCPs who do not check their EHR e-mail inbox.

In this example, the next time the PDSA cycle is completed, the new approach—using electronic fax for PCPs who don’t check their EHR e-mail while using e-mail for those who check it—will be employed, measured, and further improved in iterative cycles.

Gap Analysis

Another way you can use the “Key Principles and Characteristics” is to do a gap analysis of your HMG. You can assess the current state of your HMG against the “Key Principles and Characteristics,” which can be viewed as an ideal state. The gap between the current and the ideal state can be a roadmap to improvement for your HMG.

For an example of a large HMG’s gap analysis, see “TeamHealth Hospital Medicine Shares Performance Stats” in the August 2014 issue of The Hospitalist.

Strategic Planning

You may be thinking about taking a block of time to devote to your group’s strategic planning. The “Key Principles and Characteristics” is the ideal framework for such planning. You can use the document as a backdrop to your SWOT (strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats) analysis, which forms the basis of your HMG strategic planning activities.

Keep Your Resolution

One of the best ways to maintain your new habit in the New Year is to let others know of your resolution. In the case of your “Key Principles and Characteristics” resolution, announce your plans at the next monthly meeting of your HMG, and find a way to involve other group members in the project. You might assign a single principle or characteristic to each group member, who is tasked with doing a QI project and reporting on the results at a future date. Or, group members can engage in a portion of a gap analysis or SWOT analysis.

No matter how you use the “Key Principles and Characteristics,” I hope they will guide your HMG to a happy, healthy, and effective 2015!

Reference

In the heart of the holiday season’s gluttony (and the challenges of staffing the holidays), we need something to get us excited for 2015. Let me suggest that you resolve to use “The Key Principles and Characteristics of an Effective Hospital Medicine Group: An Assessment Guide for Hospitals and Hospitalists” to trim those holiday pounds and make your hospitalist group (HMG) fitter than ever.1

When we published the “Key Principles and Characteristics” in the Journal of Hospital Medicine in February, we intended it to be “aspirational, helping to raise the bar for the specialty of hospital medicine.”1 The author group’s intent was to provide a framework for quality improvement at the HMG level. One can use the 10 principles and 47 characteristics as a basis for self-assessment within the cycle of quality improvement. I will provide an illustration of how a group might utilize the guide to improve its performance using an example and W. Edward Deming’s classic plan-do-study-act (PDSA) cycle.

Principle 6: The HMG supports care coordination across settings.

Characteristic 6.1: The HMG has systems in place to ensure effective and reliable communication with the patient’s primary care provider and/or other providers involved in the patient’s care in the nonacute care setting.

Plan

This phase involves identifying a goal, setting success metrics, and putting a plan into action.

Example: 90% of primary care providers (PCPs) will receive a discharge summary within 24 hours of discharge.

Do

Here the key components of the plan are implemented.

Example: All referring PCPs’ preferred methods of communication and contact information are documented. The HMG has the ability to utilize such communication, e.g. electronic health record (EHR) e-mail or electronic fax. All hospitalists prepare a discharge summary in real time.

Study

In this phase, outcomes are assessed for success and barriers.

Example: Although 97% of discharge summaries are transmitted according to the PCPs’ preferred communication, PCPs state that they received it only 78% of the time.

Act

This is where the lessons learned throughout the process are integrated to adjust the methods, the goal, or the approach in general. Then the entire cycle is repeated.

Example: Even though most PCPs are on the same EHR system as the hospitalists, they don’t check their EHR e-mail (even though during the Plan phase they said they did). Their office staff uses electronic fax, so that will be the method of communication for the PCPs who do not check their EHR e-mail inbox.

In this example, the next time the PDSA cycle is completed, the new approach—using electronic fax for PCPs who don’t check their EHR e-mail while using e-mail for those who check it—will be employed, measured, and further improved in iterative cycles.

Gap Analysis

Another way you can use the “Key Principles and Characteristics” is to do a gap analysis of your HMG. You can assess the current state of your HMG against the “Key Principles and Characteristics,” which can be viewed as an ideal state. The gap between the current and the ideal state can be a roadmap to improvement for your HMG.

For an example of a large HMG’s gap analysis, see “TeamHealth Hospital Medicine Shares Performance Stats” in the August 2014 issue of The Hospitalist.

Strategic Planning

You may be thinking about taking a block of time to devote to your group’s strategic planning. The “Key Principles and Characteristics” is the ideal framework for such planning. You can use the document as a backdrop to your SWOT (strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats) analysis, which forms the basis of your HMG strategic planning activities.

Keep Your Resolution

One of the best ways to maintain your new habit in the New Year is to let others know of your resolution. In the case of your “Key Principles and Characteristics” resolution, announce your plans at the next monthly meeting of your HMG, and find a way to involve other group members in the project. You might assign a single principle or characteristic to each group member, who is tasked with doing a QI project and reporting on the results at a future date. Or, group members can engage in a portion of a gap analysis or SWOT analysis.

No matter how you use the “Key Principles and Characteristics,” I hope they will guide your HMG to a happy, healthy, and effective 2015!

Reference

In the heart of the holiday season’s gluttony (and the challenges of staffing the holidays), we need something to get us excited for 2015. Let me suggest that you resolve to use “The Key Principles and Characteristics of an Effective Hospital Medicine Group: An Assessment Guide for Hospitals and Hospitalists” to trim those holiday pounds and make your hospitalist group (HMG) fitter than ever.1

When we published the “Key Principles and Characteristics” in the Journal of Hospital Medicine in February, we intended it to be “aspirational, helping to raise the bar for the specialty of hospital medicine.”1 The author group’s intent was to provide a framework for quality improvement at the HMG level. One can use the 10 principles and 47 characteristics as a basis for self-assessment within the cycle of quality improvement. I will provide an illustration of how a group might utilize the guide to improve its performance using an example and W. Edward Deming’s classic plan-do-study-act (PDSA) cycle.

Principle 6: The HMG supports care coordination across settings.

Characteristic 6.1: The HMG has systems in place to ensure effective and reliable communication with the patient’s primary care provider and/or other providers involved in the patient’s care in the nonacute care setting.

Plan

This phase involves identifying a goal, setting success metrics, and putting a plan into action.

Example: 90% of primary care providers (PCPs) will receive a discharge summary within 24 hours of discharge.

Do

Here the key components of the plan are implemented.

Example: All referring PCPs’ preferred methods of communication and contact information are documented. The HMG has the ability to utilize such communication, e.g. electronic health record (EHR) e-mail or electronic fax. All hospitalists prepare a discharge summary in real time.

Study

In this phase, outcomes are assessed for success and barriers.

Example: Although 97% of discharge summaries are transmitted according to the PCPs’ preferred communication, PCPs state that they received it only 78% of the time.

Act

This is where the lessons learned throughout the process are integrated to adjust the methods, the goal, or the approach in general. Then the entire cycle is repeated.

Example: Even though most PCPs are on the same EHR system as the hospitalists, they don’t check their EHR e-mail (even though during the Plan phase they said they did). Their office staff uses electronic fax, so that will be the method of communication for the PCPs who do not check their EHR e-mail inbox.

In this example, the next time the PDSA cycle is completed, the new approach—using electronic fax for PCPs who don’t check their EHR e-mail while using e-mail for those who check it—will be employed, measured, and further improved in iterative cycles.

Gap Analysis

Another way you can use the “Key Principles and Characteristics” is to do a gap analysis of your HMG. You can assess the current state of your HMG against the “Key Principles and Characteristics,” which can be viewed as an ideal state. The gap between the current and the ideal state can be a roadmap to improvement for your HMG.

For an example of a large HMG’s gap analysis, see “TeamHealth Hospital Medicine Shares Performance Stats” in the August 2014 issue of The Hospitalist.

Strategic Planning

You may be thinking about taking a block of time to devote to your group’s strategic planning. The “Key Principles and Characteristics” is the ideal framework for such planning. You can use the document as a backdrop to your SWOT (strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats) analysis, which forms the basis of your HMG strategic planning activities.

Keep Your Resolution

One of the best ways to maintain your new habit in the New Year is to let others know of your resolution. In the case of your “Key Principles and Characteristics” resolution, announce your plans at the next monthly meeting of your HMG, and find a way to involve other group members in the project. You might assign a single principle or characteristic to each group member, who is tasked with doing a QI project and reporting on the results at a future date. Or, group members can engage in a portion of a gap analysis or SWOT analysis.

No matter how you use the “Key Principles and Characteristics,” I hope they will guide your HMG to a happy, healthy, and effective 2015!

Reference

Homecare Will Help You Achieve the Triple Aim

Where there is variation, there is room for improvement. The Institute of Medicine’s report on geographic variation in Medicare spending concluded that the largest contributor to overall spending variation is spending for post-acute care services.1 Furthermore, we know that a significant amount of overall spending is devoted to post-acute care. For example, for patients hospitalized with a flare-up of a chronic condition like COPD or heart failure, Medicare spends nearly as much on post-acute care and readmissions in the first 30 days after discharge as it does on the initial admission.1

What does this mean for hospitalists?

Numerous research articles and quality improvement projects have focused on what makes a good hospital discharge or hand off to the ‘next provider of care’; however, hospitalists are increasingly participating in value-based payment programs like accountable care organizations (ACOs), risk contracts, and bundled payments. This means they must begin to pay attention to the cost side of the value equation (quality divided by cost) as it relates to hospital discharge.

A day of home care represents a more cost-effective alternative than a day of care in a skilled nursing facility (SNF). Hospitalists who can identify those patients who are appropriate to send home with home health services—and who otherwise would have gone to a SNF—will serve the dual goals of improving patient experience and decreasing costs.

Hospitalists will need to develop a decision-making process that determines the appropriate level of care for the patient after discharge. The decision-making process should address questions like:

- What skilled services lead a patient to go to a SNF instead of home with home health?

- Which patients go to a SNF instead of home simply because they don’t have family or a caregiver to help them with activities of daily living?

- Are there services requiring a nurse or a therapist that can’t be delivered in the home?

Hospitalists also will need to develop a more intimate understanding of the following levels of care:

- Skilled nursing includes management of a nursing care plan, assessment of a patient’s changing condition, and services like wound care, infusion therapy, and management of medications, feeding or drainage tubes, and pain.

- Skilled rehabilitation refers to the array of services provided by physical, occupational, speech, and respiratory therapists.

- Custodial care, usually supplied by a home health aid or family member, includes help with activities of daily living (feeding, dressing, bathing, grooming, personal hygiene, and toileting).

It should be noted that most skilled nursing or therapy services can be delivered in the home setting if the patient’s custodial care needs are met—a big ‘if’ in some cases. Some patients go to a SNF because they require three or more skilled nursing or therapy services, and it is therefore impractical for them to go home.

Here are my suggestions to hospitalists seeking to reengineer the discharge process with the goals of “right-sizing” the number of patients who go to SNFs and optimizing the utilization of home healthcare services:

- Become familiar with the range of post-acute care providers and care coordination services in your community.

- Refer any patient who wishes to go home, either directly or after a SNF stay, for a home care evaluation. Home care agencies are experts in determining if and how patients can return home.

- If a need for help with activities of daily living is the major barrier to having a patient discharged to home, create a system in which case management develops a custodial care plan with the patient and caregivers during the inpatient stay. Currently, this step is delayed until well into the SNF stay and may prolong that stay. Such a plan includes a financial analysis, screening for Medicaid eligibility, and evaluating whether a family member can assume some or all of the custodial care needs.

- If a patient is being discharged to a SNF, review the list of needed services leading to the SNF transfer. Ask the case manager if these services can be provided in the home. If not, then why?

- Bed capacity permitting, consider keeping patients who are functionally improving in the hospital an extra day so they can be discharged directly home instead of to a SNF.2

In his seminal work, The Innovator’s Dilemma, Clayton Christensen describes “disruptive innovation” as that which gives rise to products or services that are cheaper, simpler, and more convenient to use. Even though home care has been around for a while, there is a sizeable group of patients, especially in geographic areas of high SNF spending, who might be better served in the home environment. As we create better systems under value-based payment, we should see an increase in the use of home healthcare as a disruptive innovation when applied to appropriate patients transitioning out of the hospital or a SNF.

Dr. Whitcomb is Chief Medical Officer of Remedy Partners. He is co-founder and past president of SHM. Email him at wfwhit@comcast.net.

References

Where there is variation, there is room for improvement. The Institute of Medicine’s report on geographic variation in Medicare spending concluded that the largest contributor to overall spending variation is spending for post-acute care services.1 Furthermore, we know that a significant amount of overall spending is devoted to post-acute care. For example, for patients hospitalized with a flare-up of a chronic condition like COPD or heart failure, Medicare spends nearly as much on post-acute care and readmissions in the first 30 days after discharge as it does on the initial admission.1

What does this mean for hospitalists?

Numerous research articles and quality improvement projects have focused on what makes a good hospital discharge or hand off to the ‘next provider of care’; however, hospitalists are increasingly participating in value-based payment programs like accountable care organizations (ACOs), risk contracts, and bundled payments. This means they must begin to pay attention to the cost side of the value equation (quality divided by cost) as it relates to hospital discharge.

A day of home care represents a more cost-effective alternative than a day of care in a skilled nursing facility (SNF). Hospitalists who can identify those patients who are appropriate to send home with home health services—and who otherwise would have gone to a SNF—will serve the dual goals of improving patient experience and decreasing costs.

Hospitalists will need to develop a decision-making process that determines the appropriate level of care for the patient after discharge. The decision-making process should address questions like:

- What skilled services lead a patient to go to a SNF instead of home with home health?

- Which patients go to a SNF instead of home simply because they don’t have family or a caregiver to help them with activities of daily living?

- Are there services requiring a nurse or a therapist that can’t be delivered in the home?

Hospitalists also will need to develop a more intimate understanding of the following levels of care:

- Skilled nursing includes management of a nursing care plan, assessment of a patient’s changing condition, and services like wound care, infusion therapy, and management of medications, feeding or drainage tubes, and pain.

- Skilled rehabilitation refers to the array of services provided by physical, occupational, speech, and respiratory therapists.

- Custodial care, usually supplied by a home health aid or family member, includes help with activities of daily living (feeding, dressing, bathing, grooming, personal hygiene, and toileting).

It should be noted that most skilled nursing or therapy services can be delivered in the home setting if the patient’s custodial care needs are met—a big ‘if’ in some cases. Some patients go to a SNF because they require three or more skilled nursing or therapy services, and it is therefore impractical for them to go home.

Here are my suggestions to hospitalists seeking to reengineer the discharge process with the goals of “right-sizing” the number of patients who go to SNFs and optimizing the utilization of home healthcare services:

- Become familiar with the range of post-acute care providers and care coordination services in your community.

- Refer any patient who wishes to go home, either directly or after a SNF stay, for a home care evaluation. Home care agencies are experts in determining if and how patients can return home.

- If a need for help with activities of daily living is the major barrier to having a patient discharged to home, create a system in which case management develops a custodial care plan with the patient and caregivers during the inpatient stay. Currently, this step is delayed until well into the SNF stay and may prolong that stay. Such a plan includes a financial analysis, screening for Medicaid eligibility, and evaluating whether a family member can assume some or all of the custodial care needs.

- If a patient is being discharged to a SNF, review the list of needed services leading to the SNF transfer. Ask the case manager if these services can be provided in the home. If not, then why?

- Bed capacity permitting, consider keeping patients who are functionally improving in the hospital an extra day so they can be discharged directly home instead of to a SNF.2

In his seminal work, The Innovator’s Dilemma, Clayton Christensen describes “disruptive innovation” as that which gives rise to products or services that are cheaper, simpler, and more convenient to use. Even though home care has been around for a while, there is a sizeable group of patients, especially in geographic areas of high SNF spending, who might be better served in the home environment. As we create better systems under value-based payment, we should see an increase in the use of home healthcare as a disruptive innovation when applied to appropriate patients transitioning out of the hospital or a SNF.

Dr. Whitcomb is Chief Medical Officer of Remedy Partners. He is co-founder and past president of SHM. Email him at wfwhit@comcast.net.

References

Where there is variation, there is room for improvement. The Institute of Medicine’s report on geographic variation in Medicare spending concluded that the largest contributor to overall spending variation is spending for post-acute care services.1 Furthermore, we know that a significant amount of overall spending is devoted to post-acute care. For example, for patients hospitalized with a flare-up of a chronic condition like COPD or heart failure, Medicare spends nearly as much on post-acute care and readmissions in the first 30 days after discharge as it does on the initial admission.1

What does this mean for hospitalists?

Numerous research articles and quality improvement projects have focused on what makes a good hospital discharge or hand off to the ‘next provider of care’; however, hospitalists are increasingly participating in value-based payment programs like accountable care organizations (ACOs), risk contracts, and bundled payments. This means they must begin to pay attention to the cost side of the value equation (quality divided by cost) as it relates to hospital discharge.

A day of home care represents a more cost-effective alternative than a day of care in a skilled nursing facility (SNF). Hospitalists who can identify those patients who are appropriate to send home with home health services—and who otherwise would have gone to a SNF—will serve the dual goals of improving patient experience and decreasing costs.

Hospitalists will need to develop a decision-making process that determines the appropriate level of care for the patient after discharge. The decision-making process should address questions like:

- What skilled services lead a patient to go to a SNF instead of home with home health?

- Which patients go to a SNF instead of home simply because they don’t have family or a caregiver to help them with activities of daily living?

- Are there services requiring a nurse or a therapist that can’t be delivered in the home?

Hospitalists also will need to develop a more intimate understanding of the following levels of care:

- Skilled nursing includes management of a nursing care plan, assessment of a patient’s changing condition, and services like wound care, infusion therapy, and management of medications, feeding or drainage tubes, and pain.

- Skilled rehabilitation refers to the array of services provided by physical, occupational, speech, and respiratory therapists.

- Custodial care, usually supplied by a home health aid or family member, includes help with activities of daily living (feeding, dressing, bathing, grooming, personal hygiene, and toileting).

It should be noted that most skilled nursing or therapy services can be delivered in the home setting if the patient’s custodial care needs are met—a big ‘if’ in some cases. Some patients go to a SNF because they require three or more skilled nursing or therapy services, and it is therefore impractical for them to go home.

Here are my suggestions to hospitalists seeking to reengineer the discharge process with the goals of “right-sizing” the number of patients who go to SNFs and optimizing the utilization of home healthcare services:

- Become familiar with the range of post-acute care providers and care coordination services in your community.

- Refer any patient who wishes to go home, either directly or after a SNF stay, for a home care evaluation. Home care agencies are experts in determining if and how patients can return home.

- If a need for help with activities of daily living is the major barrier to having a patient discharged to home, create a system in which case management develops a custodial care plan with the patient and caregivers during the inpatient stay. Currently, this step is delayed until well into the SNF stay and may prolong that stay. Such a plan includes a financial analysis, screening for Medicaid eligibility, and evaluating whether a family member can assume some or all of the custodial care needs.

- If a patient is being discharged to a SNF, review the list of needed services leading to the SNF transfer. Ask the case manager if these services can be provided in the home. If not, then why?

- Bed capacity permitting, consider keeping patients who are functionally improving in the hospital an extra day so they can be discharged directly home instead of to a SNF.2

In his seminal work, The Innovator’s Dilemma, Clayton Christensen describes “disruptive innovation” as that which gives rise to products or services that are cheaper, simpler, and more convenient to use. Even though home care has been around for a while, there is a sizeable group of patients, especially in geographic areas of high SNF spending, who might be better served in the home environment. As we create better systems under value-based payment, we should see an increase in the use of home healthcare as a disruptive innovation when applied to appropriate patients transitioning out of the hospital or a SNF.

Dr. Whitcomb is Chief Medical Officer of Remedy Partners. He is co-founder and past president of SHM. Email him at wfwhit@comcast.net.

References

State of the Art

It has been a couple of years since Jason Stein, MD, SFHM, a hospitalist at Emory University School of Medicine in Atlanta, first reported on his experience with accountable care units (ACUs) and structured interdisciplinary bedside rounds (SIBR). With ACUs, Jason and his team undertook an “extreme makeover” of care on the hospital ward. Because most hospitalist groups are endeavoring to address team-based care, I took the opportunity to catch up with and learn from Jason, who has created an exciting and compelling approach to multidisciplinary, collaborative care in the hospital.

In 2012, Jason’s team won SHM’s Excellence in Teamwork in Quality Improvement Award, and Jason was selected as an innovation advisor to the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation. Since then, ACUs and SIBR have been implemented at a number of sites in the U.S. and abroad, and the work has been referenced by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality and the Harvard Business Review. Jason has created Centripital, a nonprofit that trains members of the hospital team to collaborate optimally around the patient and family, the central focus of care.

Here are some excerpts from my interview with Jason:

Question: What is an accountable care unit (ACU)?

Answer: We defined an ACU as a geographic inpatient care area consistently responsible for the clinical, service, and cost outcomes it produces. There are four essential design features of ACUs: 1) unit-based physician teams; 2) structured interdisciplinary bedside rounds, or SIBR; 3) unit-level performance reports; and 4) unit co-management by nurse and physician directors.

Q: What were you observing in the care of the hospitalized patient that led you to create ACUs?

A: We saw fragmentation. We saw weak cohesiveness and poor communication among doctors, nurses, and allied health professionals. HM physicians who travel all over the hospital seeing patients are living with an illusion of teamwork. In reality, to be a high-functioning team, physicians have to share time, space, and a standard way to work together with nurses, patients, and families. When we embraced this way of thinking, we realized we could be so much better than we were. The key was to re-engineer a way to really work together.

Q: What makes an ACU successful?

A: In a word, control. An ACU creates new control levers for all of the key players to have greater influence on other members of the team—nurses with doctors, doctors with nurses, patients with everyone, and vice versa. It’s actually quite simple how this happens. The ACU clinical team spends the day together, caring for the same group of patients. Everyone communicates face to face, rather than by page, text, or phone. Stronger relationships are built, and clinicians are more respectful of one another. A different level of responsiveness and accountability is created. The feeling that every person is accountable to the patient and to the other team members allows the team to gain greater control over what happens on the unit. That’s a very powerful dynamic.

SIBR further reinforces the mutual accountability on an ACU. During SIBR, each person has a chance to hear and be heard, to share their perspective, and to contribute to the care plan. Day after day, SIBR creates a positive, collaborative culture of patient care. Once clinicians realize how much control and how much self-actualization they gain on an ACU, it seems impossible to go back to the old way.

—Jason Stein, MD, SFHM

Q: What is the biggest challenge in implementing and sustaining an ACU?

A: The first challenge, of course, is that this is change. And up front—before they realize they will actually gain greater control from the ACU-SIBR model—nurses and, particularly, doctors can perceive this change as a loss of control. “You’re telling me I have to SIBR every morning? At what time? And I have to do all my primary data gathering, including a patient interview and physical exam, before SIBR? Let me stop you right there. I’m way too busy for that.”

Naturally, not everyone immediately sees that they can gain rather than lose efficiency.

Another challenge is the logistics of implementing and then maintaining unit-based physician teams. There are multiple forces that can make geographic units a challenge to create and sustain, but all the logistics are manageable.

Q: How have you helped hospitals transition from a physician-centric model to the geographic-based model?

A: The most important factor in transitioning to an ACU model is for physicians to come to terms with the reality that geography must be the primary driver of physician assignments to patients. Nurses figured this out a long time ago. Do any of us know, bedside nurses who care for patients on multiple different units? As physicians, we’re due for the same realization.

But this means sacrificing long-practiced physician-centric methods of assigning ourselves to patients: call schedules, load balancing across practice partners—even the cherished concept of continuity is a force that can be at odds with geography as the driver. The way to approach the transition to unit-based teams is to have an honest dialogue. Why do we come to work in the hospital every day? If it’s to serve physician needs first, the old model deserves our loyalty. But if the needs of our patients and families are our focus, then we should embrace models that enable us to work effectively together, to become a great team.

Q: How have ACUs performed so far?

A: In the highest-acuity ACUs, we’ve seen mortality reductions of nearly 50%. In addition, there is a wide range of anecdotal outcomes reported. Most ACUs appear to be seeing reductions in length of stay and improvements in patient satisfaction and employee engagement. One ACU reports significant reductions in average cost per patient per day. Another ACU in a geriatric unit has seen dramatic reductions in falls. Some ACUs have seen improvements in glycemic control and VTE prophylaxis, and reductions in catheter utilization.

The benefits of the model seem to be many and probably depend on the patient population, severity of illness, baseline level of performance, and the focus and ability of the unit leadership team to get the most out of the model.

Q: Will ACUs or ACU features become de rigueur in a transformed healthcare landscape?

A: It’s hard to imagine a reality where features of ACUs do not become the standard of care. Once patients and professionals experience the impact of the ACU model, there’ll be no going back. It feels like exactly what we should be doing together. Several ACU design features are reinforced pretty cogently by Richard Bohmer in a New England Journal of Medicine perspective called “The Four Habits of High-Value Health Care Organizations.”1

Q: Any final thoughts?

A: I did not imagine my career as a QI practitioner at Emory becoming so immersed in social and industrial engineering. Of course, it’s obvious to me now that it’s happened, but six years ago when I first started directing SHM’s quality course, I thought the future in HM was health IT and real-time dashboards. Now I know those things will be important, but only if we first figure out how to get our frontline interdisciplinary clinicians to work as an effective team.

Dr. Whitcomb is Chief Medical Officer of Remedy Partners. He is co-founder and past president of SHM. Email him at wfwhit@comcast.net.

Reference

It has been a couple of years since Jason Stein, MD, SFHM, a hospitalist at Emory University School of Medicine in Atlanta, first reported on his experience with accountable care units (ACUs) and structured interdisciplinary bedside rounds (SIBR). With ACUs, Jason and his team undertook an “extreme makeover” of care on the hospital ward. Because most hospitalist groups are endeavoring to address team-based care, I took the opportunity to catch up with and learn from Jason, who has created an exciting and compelling approach to multidisciplinary, collaborative care in the hospital.

In 2012, Jason’s team won SHM’s Excellence in Teamwork in Quality Improvement Award, and Jason was selected as an innovation advisor to the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation. Since then, ACUs and SIBR have been implemented at a number of sites in the U.S. and abroad, and the work has been referenced by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality and the Harvard Business Review. Jason has created Centripital, a nonprofit that trains members of the hospital team to collaborate optimally around the patient and family, the central focus of care.

Here are some excerpts from my interview with Jason:

Question: What is an accountable care unit (ACU)?

Answer: We defined an ACU as a geographic inpatient care area consistently responsible for the clinical, service, and cost outcomes it produces. There are four essential design features of ACUs: 1) unit-based physician teams; 2) structured interdisciplinary bedside rounds, or SIBR; 3) unit-level performance reports; and 4) unit co-management by nurse and physician directors.

Q: What were you observing in the care of the hospitalized patient that led you to create ACUs?

A: We saw fragmentation. We saw weak cohesiveness and poor communication among doctors, nurses, and allied health professionals. HM physicians who travel all over the hospital seeing patients are living with an illusion of teamwork. In reality, to be a high-functioning team, physicians have to share time, space, and a standard way to work together with nurses, patients, and families. When we embraced this way of thinking, we realized we could be so much better than we were. The key was to re-engineer a way to really work together.

Q: What makes an ACU successful?

A: In a word, control. An ACU creates new control levers for all of the key players to have greater influence on other members of the team—nurses with doctors, doctors with nurses, patients with everyone, and vice versa. It’s actually quite simple how this happens. The ACU clinical team spends the day together, caring for the same group of patients. Everyone communicates face to face, rather than by page, text, or phone. Stronger relationships are built, and clinicians are more respectful of one another. A different level of responsiveness and accountability is created. The feeling that every person is accountable to the patient and to the other team members allows the team to gain greater control over what happens on the unit. That’s a very powerful dynamic.

SIBR further reinforces the mutual accountability on an ACU. During SIBR, each person has a chance to hear and be heard, to share their perspective, and to contribute to the care plan. Day after day, SIBR creates a positive, collaborative culture of patient care. Once clinicians realize how much control and how much self-actualization they gain on an ACU, it seems impossible to go back to the old way.

—Jason Stein, MD, SFHM

Q: What is the biggest challenge in implementing and sustaining an ACU?

A: The first challenge, of course, is that this is change. And up front—before they realize they will actually gain greater control from the ACU-SIBR model—nurses and, particularly, doctors can perceive this change as a loss of control. “You’re telling me I have to SIBR every morning? At what time? And I have to do all my primary data gathering, including a patient interview and physical exam, before SIBR? Let me stop you right there. I’m way too busy for that.”

Naturally, not everyone immediately sees that they can gain rather than lose efficiency.

Another challenge is the logistics of implementing and then maintaining unit-based physician teams. There are multiple forces that can make geographic units a challenge to create and sustain, but all the logistics are manageable.

Q: How have you helped hospitals transition from a physician-centric model to the geographic-based model?

A: The most important factor in transitioning to an ACU model is for physicians to come to terms with the reality that geography must be the primary driver of physician assignments to patients. Nurses figured this out a long time ago. Do any of us know, bedside nurses who care for patients on multiple different units? As physicians, we’re due for the same realization.

But this means sacrificing long-practiced physician-centric methods of assigning ourselves to patients: call schedules, load balancing across practice partners—even the cherished concept of continuity is a force that can be at odds with geography as the driver. The way to approach the transition to unit-based teams is to have an honest dialogue. Why do we come to work in the hospital every day? If it’s to serve physician needs first, the old model deserves our loyalty. But if the needs of our patients and families are our focus, then we should embrace models that enable us to work effectively together, to become a great team.

Q: How have ACUs performed so far?

A: In the highest-acuity ACUs, we’ve seen mortality reductions of nearly 50%. In addition, there is a wide range of anecdotal outcomes reported. Most ACUs appear to be seeing reductions in length of stay and improvements in patient satisfaction and employee engagement. One ACU reports significant reductions in average cost per patient per day. Another ACU in a geriatric unit has seen dramatic reductions in falls. Some ACUs have seen improvements in glycemic control and VTE prophylaxis, and reductions in catheter utilization.

The benefits of the model seem to be many and probably depend on the patient population, severity of illness, baseline level of performance, and the focus and ability of the unit leadership team to get the most out of the model.

Q: Will ACUs or ACU features become de rigueur in a transformed healthcare landscape?

A: It’s hard to imagine a reality where features of ACUs do not become the standard of care. Once patients and professionals experience the impact of the ACU model, there’ll be no going back. It feels like exactly what we should be doing together. Several ACU design features are reinforced pretty cogently by Richard Bohmer in a New England Journal of Medicine perspective called “The Four Habits of High-Value Health Care Organizations.”1

Q: Any final thoughts?

A: I did not imagine my career as a QI practitioner at Emory becoming so immersed in social and industrial engineering. Of course, it’s obvious to me now that it’s happened, but six years ago when I first started directing SHM’s quality course, I thought the future in HM was health IT and real-time dashboards. Now I know those things will be important, but only if we first figure out how to get our frontline interdisciplinary clinicians to work as an effective team.

Dr. Whitcomb is Chief Medical Officer of Remedy Partners. He is co-founder and past president of SHM. Email him at wfwhit@comcast.net.

Reference

It has been a couple of years since Jason Stein, MD, SFHM, a hospitalist at Emory University School of Medicine in Atlanta, first reported on his experience with accountable care units (ACUs) and structured interdisciplinary bedside rounds (SIBR). With ACUs, Jason and his team undertook an “extreme makeover” of care on the hospital ward. Because most hospitalist groups are endeavoring to address team-based care, I took the opportunity to catch up with and learn from Jason, who has created an exciting and compelling approach to multidisciplinary, collaborative care in the hospital.

In 2012, Jason’s team won SHM’s Excellence in Teamwork in Quality Improvement Award, and Jason was selected as an innovation advisor to the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation. Since then, ACUs and SIBR have been implemented at a number of sites in the U.S. and abroad, and the work has been referenced by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality and the Harvard Business Review. Jason has created Centripital, a nonprofit that trains members of the hospital team to collaborate optimally around the patient and family, the central focus of care.

Here are some excerpts from my interview with Jason:

Question: What is an accountable care unit (ACU)?

Answer: We defined an ACU as a geographic inpatient care area consistently responsible for the clinical, service, and cost outcomes it produces. There are four essential design features of ACUs: 1) unit-based physician teams; 2) structured interdisciplinary bedside rounds, or SIBR; 3) unit-level performance reports; and 4) unit co-management by nurse and physician directors.

Q: What were you observing in the care of the hospitalized patient that led you to create ACUs?

A: We saw fragmentation. We saw weak cohesiveness and poor communication among doctors, nurses, and allied health professionals. HM physicians who travel all over the hospital seeing patients are living with an illusion of teamwork. In reality, to be a high-functioning team, physicians have to share time, space, and a standard way to work together with nurses, patients, and families. When we embraced this way of thinking, we realized we could be so much better than we were. The key was to re-engineer a way to really work together.

Q: What makes an ACU successful?

A: In a word, control. An ACU creates new control levers for all of the key players to have greater influence on other members of the team—nurses with doctors, doctors with nurses, patients with everyone, and vice versa. It’s actually quite simple how this happens. The ACU clinical team spends the day together, caring for the same group of patients. Everyone communicates face to face, rather than by page, text, or phone. Stronger relationships are built, and clinicians are more respectful of one another. A different level of responsiveness and accountability is created. The feeling that every person is accountable to the patient and to the other team members allows the team to gain greater control over what happens on the unit. That’s a very powerful dynamic.

SIBR further reinforces the mutual accountability on an ACU. During SIBR, each person has a chance to hear and be heard, to share their perspective, and to contribute to the care plan. Day after day, SIBR creates a positive, collaborative culture of patient care. Once clinicians realize how much control and how much self-actualization they gain on an ACU, it seems impossible to go back to the old way.

—Jason Stein, MD, SFHM

Q: What is the biggest challenge in implementing and sustaining an ACU?

A: The first challenge, of course, is that this is change. And up front—before they realize they will actually gain greater control from the ACU-SIBR model—nurses and, particularly, doctors can perceive this change as a loss of control. “You’re telling me I have to SIBR every morning? At what time? And I have to do all my primary data gathering, including a patient interview and physical exam, before SIBR? Let me stop you right there. I’m way too busy for that.”

Naturally, not everyone immediately sees that they can gain rather than lose efficiency.

Another challenge is the logistics of implementing and then maintaining unit-based physician teams. There are multiple forces that can make geographic units a challenge to create and sustain, but all the logistics are manageable.

Q: How have you helped hospitals transition from a physician-centric model to the geographic-based model?

A: The most important factor in transitioning to an ACU model is for physicians to come to terms with the reality that geography must be the primary driver of physician assignments to patients. Nurses figured this out a long time ago. Do any of us know, bedside nurses who care for patients on multiple different units? As physicians, we’re due for the same realization.

But this means sacrificing long-practiced physician-centric methods of assigning ourselves to patients: call schedules, load balancing across practice partners—even the cherished concept of continuity is a force that can be at odds with geography as the driver. The way to approach the transition to unit-based teams is to have an honest dialogue. Why do we come to work in the hospital every day? If it’s to serve physician needs first, the old model deserves our loyalty. But if the needs of our patients and families are our focus, then we should embrace models that enable us to work effectively together, to become a great team.

Q: How have ACUs performed so far?

A: In the highest-acuity ACUs, we’ve seen mortality reductions of nearly 50%. In addition, there is a wide range of anecdotal outcomes reported. Most ACUs appear to be seeing reductions in length of stay and improvements in patient satisfaction and employee engagement. One ACU reports significant reductions in average cost per patient per day. Another ACU in a geriatric unit has seen dramatic reductions in falls. Some ACUs have seen improvements in glycemic control and VTE prophylaxis, and reductions in catheter utilization.

The benefits of the model seem to be many and probably depend on the patient population, severity of illness, baseline level of performance, and the focus and ability of the unit leadership team to get the most out of the model.

Q: Will ACUs or ACU features become de rigueur in a transformed healthcare landscape?

A: It’s hard to imagine a reality where features of ACUs do not become the standard of care. Once patients and professionals experience the impact of the ACU model, there’ll be no going back. It feels like exactly what we should be doing together. Several ACU design features are reinforced pretty cogently by Richard Bohmer in a New England Journal of Medicine perspective called “The Four Habits of High-Value Health Care Organizations.”1

Q: Any final thoughts?

A: I did not imagine my career as a QI practitioner at Emory becoming so immersed in social and industrial engineering. Of course, it’s obvious to me now that it’s happened, but six years ago when I first started directing SHM’s quality course, I thought the future in HM was health IT and real-time dashboards. Now I know those things will be important, but only if we first figure out how to get our frontline interdisciplinary clinicians to work as an effective team.

Dr. Whitcomb is Chief Medical Officer of Remedy Partners. He is co-founder and past president of SHM. Email him at wfwhit@comcast.net.

Reference

Hospitalist Pay Shifts from Volume to Value with Global Payment System

The move to paying hospitals and physicians based on value instead of volume is well underway. As programs ultimately designed to offer a global payment for a population (ACOs) or an episode of care (bundled payment) expand, we are left with this paradox: How do we reward physicians for working harder and seeing more patients under a global payment system that encourages physicians and hospitals to do less?

It appears that the existing fee-for-service payment system will need to form the scaffolding of any new, value-based system. Physicians must document the services they provide, leaving a “footprint” that can be recognized and rewarded. Without a record of the volume of services, physicians will have no incentive to see more patients during times of increased demand. This is what we often experience with straight-salary arrangements—physicians question why they should work harder for no additional compensation.

Through the ACO lens, Bruce Landon, professor of health care policy at Harvard Medical School, states the challenge in a different way: “The fundamental questions become how ACOs will divide their global budgets and how their physicians and service providers will be reimbursed. Thus, this system for determining who has earned what portion of payments—keeping score—is likely to be crucially important to the success of these new models of care.”1

In another article addressing value-based payment for physicians, Eric Stecker, MD, MPH, and Steve Schroeder, MD, argue that, due to their longevity and resilience, relative value units (RVUs), instead of physician-level capitation, straight salary, or salary with pay for performance incentives, should be the preferred mechanism to reimburse physicians based on value.2

I’d like to further develop the idea of an RVU-centric approach to value-based physician reimbursement, specifically discussing the case of hospitalists.

In Table 1, I provide examples of “value-based elements” to be added to an RVU reimbursement system. I chose measures related to three hospital-based quality programs: readmission reduction, hospital-acquired conditions, and value-based purchasing; however, one could choose hospitalist-relevant quality measures from other programs, such as ACOs, meaningful use, outpatient quality reporting (for observation patients), bundled payments, or a broad range of other domains. I selected only process measures, because outcome measures such as mortality or readmission rates suffer from sample size that is too small and risk adjustment too inadequate to be applied to individual physician payment.

Drs. Stecker and Schroeder offer an observation that is especially important to hospitalists: “Although RVUs are traditionally used for episodes of care provided by individual clinicians for individual patients, activities linked to RVUs could be more broadly defined to include team-based and supervisory clinical activities as well.”2 In the table, I include “multidisciplinary discharge planning rounds” as a potential measure. One can envision other team-based or supervisory activities involving hospitalists collaborating with nurses, pharmacists, or case managers working on a catheter-UTI bundle, high-risk medication counseling, or readmission risk assessment—with each activity linked to RVUs.

The implementation of an RVU system incorporating quality measures would be aided by documentation templates in the electronic medical record, similar to templates emerging for care bundles like central line blood stream infection. Value-based RVUs would have challenges, such as the need to change the measures over time and the system gaming inherent in any incentive design. Details of implementing the program would need to be worked out, such as attributing measures to individual physicians/providers or limiting to one the number of times certain measures are fulfilled per hospitalization.

Once established, a value-based RVU system could replace the complex and variable physician compensation landscape that exists today. As has always been the case, an RVU system could form the basis of a production incentive. Such a system could be implemented on existing billing software systems, would not require additional resources to administer, and is likely to find acceptance among hospitalists, because it is something most are already accustomed to.

Current efforts to pay physicians based on value are facing substantial headwinds. The Value-Based Payment Modifier has been criticized for being too complex, while the Physician Quality Reporting System, in place since 2007, has been plagued by a “dismal” adoption rate by physicians and has been noted to “reflect a vanishingly small part of professional activities in most clinical specialties.”3 The time may be right to rethink physician value-based payment and integrate it into the existing, time-honored RVU payment system.

Dr. Whitcomb is Chief Medical Officer of Remedy Partners. He is co-founder and past president of SHM. Email him at wfwhit@comcast.net.

References

- Landon BE. Keeping score under a global payment system. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(5):393-395.

- Stecker EC, Schroeder SA. Adding value to relative-value units. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(23):2176-2179.

- Berenson RA, Kaye DR. Grading a physician’s value — the misapplication of performance measurement. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(22):2079-2078.

The move to paying hospitals and physicians based on value instead of volume is well underway. As programs ultimately designed to offer a global payment for a population (ACOs) or an episode of care (bundled payment) expand, we are left with this paradox: How do we reward physicians for working harder and seeing more patients under a global payment system that encourages physicians and hospitals to do less?

It appears that the existing fee-for-service payment system will need to form the scaffolding of any new, value-based system. Physicians must document the services they provide, leaving a “footprint” that can be recognized and rewarded. Without a record of the volume of services, physicians will have no incentive to see more patients during times of increased demand. This is what we often experience with straight-salary arrangements—physicians question why they should work harder for no additional compensation.

Through the ACO lens, Bruce Landon, professor of health care policy at Harvard Medical School, states the challenge in a different way: “The fundamental questions become how ACOs will divide their global budgets and how their physicians and service providers will be reimbursed. Thus, this system for determining who has earned what portion of payments—keeping score—is likely to be crucially important to the success of these new models of care.”1

In another article addressing value-based payment for physicians, Eric Stecker, MD, MPH, and Steve Schroeder, MD, argue that, due to their longevity and resilience, relative value units (RVUs), instead of physician-level capitation, straight salary, or salary with pay for performance incentives, should be the preferred mechanism to reimburse physicians based on value.2

I’d like to further develop the idea of an RVU-centric approach to value-based physician reimbursement, specifically discussing the case of hospitalists.

In Table 1, I provide examples of “value-based elements” to be added to an RVU reimbursement system. I chose measures related to three hospital-based quality programs: readmission reduction, hospital-acquired conditions, and value-based purchasing; however, one could choose hospitalist-relevant quality measures from other programs, such as ACOs, meaningful use, outpatient quality reporting (for observation patients), bundled payments, or a broad range of other domains. I selected only process measures, because outcome measures such as mortality or readmission rates suffer from sample size that is too small and risk adjustment too inadequate to be applied to individual physician payment.

Drs. Stecker and Schroeder offer an observation that is especially important to hospitalists: “Although RVUs are traditionally used for episodes of care provided by individual clinicians for individual patients, activities linked to RVUs could be more broadly defined to include team-based and supervisory clinical activities as well.”2 In the table, I include “multidisciplinary discharge planning rounds” as a potential measure. One can envision other team-based or supervisory activities involving hospitalists collaborating with nurses, pharmacists, or case managers working on a catheter-UTI bundle, high-risk medication counseling, or readmission risk assessment—with each activity linked to RVUs.

The implementation of an RVU system incorporating quality measures would be aided by documentation templates in the electronic medical record, similar to templates emerging for care bundles like central line blood stream infection. Value-based RVUs would have challenges, such as the need to change the measures over time and the system gaming inherent in any incentive design. Details of implementing the program would need to be worked out, such as attributing measures to individual physicians/providers or limiting to one the number of times certain measures are fulfilled per hospitalization.

Once established, a value-based RVU system could replace the complex and variable physician compensation landscape that exists today. As has always been the case, an RVU system could form the basis of a production incentive. Such a system could be implemented on existing billing software systems, would not require additional resources to administer, and is likely to find acceptance among hospitalists, because it is something most are already accustomed to.

Current efforts to pay physicians based on value are facing substantial headwinds. The Value-Based Payment Modifier has been criticized for being too complex, while the Physician Quality Reporting System, in place since 2007, has been plagued by a “dismal” adoption rate by physicians and has been noted to “reflect a vanishingly small part of professional activities in most clinical specialties.”3 The time may be right to rethink physician value-based payment and integrate it into the existing, time-honored RVU payment system.

Dr. Whitcomb is Chief Medical Officer of Remedy Partners. He is co-founder and past president of SHM. Email him at wfwhit@comcast.net.

References

- Landon BE. Keeping score under a global payment system. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(5):393-395.

- Stecker EC, Schroeder SA. Adding value to relative-value units. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(23):2176-2179.

- Berenson RA, Kaye DR. Grading a physician’s value — the misapplication of performance measurement. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(22):2079-2078.

The move to paying hospitals and physicians based on value instead of volume is well underway. As programs ultimately designed to offer a global payment for a population (ACOs) or an episode of care (bundled payment) expand, we are left with this paradox: How do we reward physicians for working harder and seeing more patients under a global payment system that encourages physicians and hospitals to do less?