User login

There is evidence that gout and heart disease are mechanistically linked by inflammation and patients with gout are at elevated risk for cardiovascular disease (CVD). But do gout flares, on their own, affect short-term risk for CV events? A new analysis based on records from British medical practices suggests that might be the case.

Risk for myocardial infarction or stroke climbed in the weeks after individual gout flare-ups in the study’s more than 60,000 patients with a recent gout diagnosis. The jump in risk, significant but small in absolute terms, held for about 4 months in the case-control study before going away.

A sensitivity analysis that excluded patients who already had CVD when their gout was diagnosed yielded similar results.

The observational study isn’t able to show that gout flares themselves transiently raise the risk for MI or stroke, but it’s enough to send a cautionary message to physicians who care for patients with gout, rheumatologist Abhishek Abhishek, PhD, Nottingham (England) City Hospital, said in an interview.

In such patients who also have conditions like hypertension, diabetes, or dyslipidemia, or a history of heart disease, he said, it’s important “to manage risk factors really aggressively, knowing that when these patients have a gout flare, there’s a temporary increase in risk of a cardiovascular event.”

Managing their absolute CV risk – whether with drug therapy, lifestyle changes, or other interventions – should help limit the transient jump in risk for MI or stroke following a gout flare, proposed Dr. Abhishek, who is senior author on the study published in JAMA, with lead author Edoardo Cipolletta, MD, also from Nottingham City Hospital.

First robust evidence

The case-control study, which involved more than 60,000 patients with a recent gout diagnosis, some who went on to have MI or stroke, looked at rates of such events at different time intervals after gout flares. Those who experienced such events showed a more than 90% increased likelihood of a gout flare-up in the preceding 60 days, a greater than 50% chance of a flare between 60 and 120 days before the event, but no increased likelihood prior to 120 days before the event.

Such a link between gout flares and CV events “has been suspected but never proven,” observed rheumatologist Hyon K. Choi, MD, Harvard Medical School, Boston, who was not associated with the analysis. “This is the first time it has actually been shown in a robust way,” he said in an interview.

The study suggests a “likely causative relationship” between gout flares and CV events, but – as the published report noted – has limitations like any observational study, said Dr. Choi, who also directs the Gout & Crystal Arthropathy Center at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston. “Hopefully, this can be replicated in other cohorts.”

The analysis controlled for a number of relevant potential confounders, he noted, but couldn’t account for all issues that could argue against gout flares as a direct cause of the MIs and strokes.

Gout attacks are a complex experience with a range of potential indirect effects on CV risk, Dr. Choi observed. They can immobilize patients, possibly raising their risk for thrombotic events, for example. They can be exceptionally painful, which causes stress and can lead to frequent or chronic use of glucocorticoids or NSAIDs, all of which can exacerbate high blood pressure and possibly worsen CV risk.

A unique insight

The timing of gout flares relative to acute vascular events hasn’t been fully explored, observed an accompanying editorial. The current study’s “unique insight,” it stated, “is that disease activity from gout was associated with an incremental increase in risk for acute vascular events during the time period immediately following the gout flare.”

Although the study is observational, a “large body of evidence from animal and human research, mechanistic insights, and clinical interventions” support an association between flares and vascular events and “make a causal link eminently reasonable,” stated the editorialists, Jeffrey L. Anderson, MD, and Kirk U. Knowlton, MD, both with Intermountain Medical Center, Salt Lake City, Utah.

The findings, they wrote, “should alert clinicians and patients to the increased cardiovascular risk in the weeks beginning after a gout flare and should focus attention on optimizing preventive measures.” Those can include “lifestyle measures and standard risk-factor control including adherence to diet, statins, anti-inflammatory drugs (e.g., aspirin, colchicine), smoking cessation, diabetic and blood pressure control, and antithrombotic medications as indicated.”

Dr. Choi said the current results argue for more liberal use of colchicine, and for preferring colchicine over other anti-inflammatories, in patients with gout and traditional CV risk factors, given multiple randomized trials supporting the drug’s use in such cases. “If you use colchicine, you are covering their heart disease risk as well as their gout. It’s two birds with one stone.”

Nested case-control study

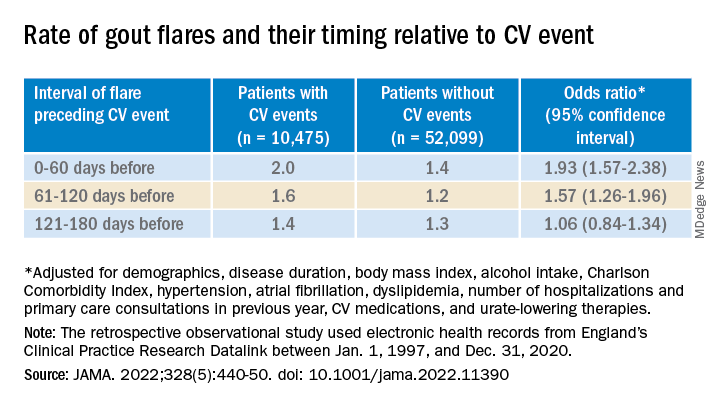

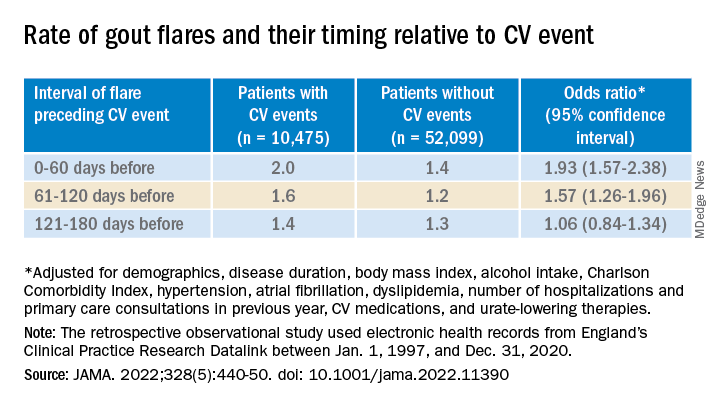

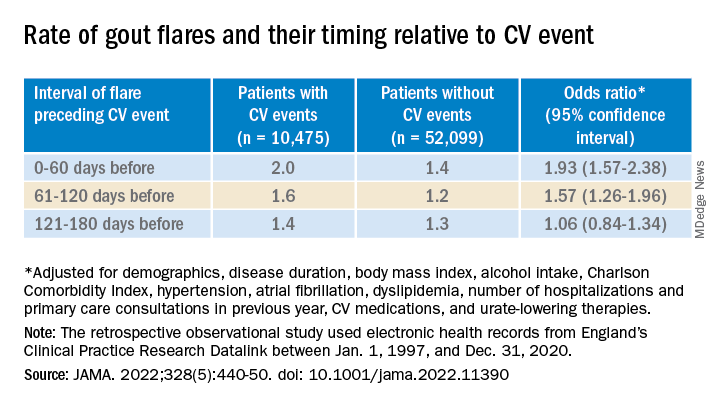

The investigators accessed electronic health records from 96,153 patients with recently diagnosed gout in England from 1997 to 2020; the cohort’s mean age was about 76 years, and 69% of participants were men. They matched 10,475 patients with at least one CV event to 52,099 others who didn’t have such an event by age, sex, and time from gout diagnosis. In each matched set of patients, those not experiencing a CV event were assigned a flare-to-event interval based on their matching with patients who did experience such an event.

Those with CV events, compared with patients without an event, had a greater than 90% increased likelihood of experiencing a gout flare-up in the 60 days preceding the event, a more than 50% greater chance of a flare-up 60-120 days before the CV event, but no increased likelihood more than 120 days before the event.

A self-controlled case series based on the same overall cohort with gout yielded similar results while sidestepping any potential for residual confounding, an inherent concern with any case–control analysis, the report notes. It involved 1,421 patients with one or more gout flare and at least one MI or stroke after the diagnosis of gout.

Among that cohort, the CV-event incidence rate ratio, adjusted for age and season of the year, by time interval after a gout flare, was 1.89 (95% confidence interval, 1.54-2.30) at 0-60 days, 1.64 (95% CI, 1.45-1.86) at 61-120 days, and1.29 (95% CI, 1.02-1.64) at 121-180 days.

Also similar, the report noted, were results of several sensitivity analyses, including one that excluded patients with confirmed CVD before their gout diagnosis; another that left out patients at low to moderate CV risk; and one that considered only gout flares treated with colchicine, corticosteroids, or NSAIDs.

The incremental CV event risks observed after flares in the study were small, which “has implications for both cost effectiveness and clinical relevance,” observed Dr. Anderson and Dr. Knowlton.

“An alternative to universal augmentation of cardiovascular risk prevention with therapies among patients with gout flares,” they wrote, would be “to further stratify risk by defining a group at highest near-term risk.” Such interventions could potentially be guided by markers of CV risk such as, for example, levels of high-sensitivity C-reactive protein or lipoprotein(a), or plaque burden on coronary-artery calcium scans.

Dr. Abhishek, Dr. Cipolletta, and the other authors reported no competing interests. Dr. Choi disclosed research support from Ironwood and Horizon; and consulting fees from Ironwood, Selecta, Horizon, Takeda, Kowa, and Vaxart. Dr. Anderson disclosed receiving grants to his institution from Novartis and Milestone.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

There is evidence that gout and heart disease are mechanistically linked by inflammation and patients with gout are at elevated risk for cardiovascular disease (CVD). But do gout flares, on their own, affect short-term risk for CV events? A new analysis based on records from British medical practices suggests that might be the case.

Risk for myocardial infarction or stroke climbed in the weeks after individual gout flare-ups in the study’s more than 60,000 patients with a recent gout diagnosis. The jump in risk, significant but small in absolute terms, held for about 4 months in the case-control study before going away.

A sensitivity analysis that excluded patients who already had CVD when their gout was diagnosed yielded similar results.

The observational study isn’t able to show that gout flares themselves transiently raise the risk for MI or stroke, but it’s enough to send a cautionary message to physicians who care for patients with gout, rheumatologist Abhishek Abhishek, PhD, Nottingham (England) City Hospital, said in an interview.

In such patients who also have conditions like hypertension, diabetes, or dyslipidemia, or a history of heart disease, he said, it’s important “to manage risk factors really aggressively, knowing that when these patients have a gout flare, there’s a temporary increase in risk of a cardiovascular event.”

Managing their absolute CV risk – whether with drug therapy, lifestyle changes, or other interventions – should help limit the transient jump in risk for MI or stroke following a gout flare, proposed Dr. Abhishek, who is senior author on the study published in JAMA, with lead author Edoardo Cipolletta, MD, also from Nottingham City Hospital.

First robust evidence

The case-control study, which involved more than 60,000 patients with a recent gout diagnosis, some who went on to have MI or stroke, looked at rates of such events at different time intervals after gout flares. Those who experienced such events showed a more than 90% increased likelihood of a gout flare-up in the preceding 60 days, a greater than 50% chance of a flare between 60 and 120 days before the event, but no increased likelihood prior to 120 days before the event.

Such a link between gout flares and CV events “has been suspected but never proven,” observed rheumatologist Hyon K. Choi, MD, Harvard Medical School, Boston, who was not associated with the analysis. “This is the first time it has actually been shown in a robust way,” he said in an interview.

The study suggests a “likely causative relationship” between gout flares and CV events, but – as the published report noted – has limitations like any observational study, said Dr. Choi, who also directs the Gout & Crystal Arthropathy Center at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston. “Hopefully, this can be replicated in other cohorts.”

The analysis controlled for a number of relevant potential confounders, he noted, but couldn’t account for all issues that could argue against gout flares as a direct cause of the MIs and strokes.

Gout attacks are a complex experience with a range of potential indirect effects on CV risk, Dr. Choi observed. They can immobilize patients, possibly raising their risk for thrombotic events, for example. They can be exceptionally painful, which causes stress and can lead to frequent or chronic use of glucocorticoids or NSAIDs, all of which can exacerbate high blood pressure and possibly worsen CV risk.

A unique insight

The timing of gout flares relative to acute vascular events hasn’t been fully explored, observed an accompanying editorial. The current study’s “unique insight,” it stated, “is that disease activity from gout was associated with an incremental increase in risk for acute vascular events during the time period immediately following the gout flare.”

Although the study is observational, a “large body of evidence from animal and human research, mechanistic insights, and clinical interventions” support an association between flares and vascular events and “make a causal link eminently reasonable,” stated the editorialists, Jeffrey L. Anderson, MD, and Kirk U. Knowlton, MD, both with Intermountain Medical Center, Salt Lake City, Utah.

The findings, they wrote, “should alert clinicians and patients to the increased cardiovascular risk in the weeks beginning after a gout flare and should focus attention on optimizing preventive measures.” Those can include “lifestyle measures and standard risk-factor control including adherence to diet, statins, anti-inflammatory drugs (e.g., aspirin, colchicine), smoking cessation, diabetic and blood pressure control, and antithrombotic medications as indicated.”

Dr. Choi said the current results argue for more liberal use of colchicine, and for preferring colchicine over other anti-inflammatories, in patients with gout and traditional CV risk factors, given multiple randomized trials supporting the drug’s use in such cases. “If you use colchicine, you are covering their heart disease risk as well as their gout. It’s two birds with one stone.”

Nested case-control study

The investigators accessed electronic health records from 96,153 patients with recently diagnosed gout in England from 1997 to 2020; the cohort’s mean age was about 76 years, and 69% of participants were men. They matched 10,475 patients with at least one CV event to 52,099 others who didn’t have such an event by age, sex, and time from gout diagnosis. In each matched set of patients, those not experiencing a CV event were assigned a flare-to-event interval based on their matching with patients who did experience such an event.

Those with CV events, compared with patients without an event, had a greater than 90% increased likelihood of experiencing a gout flare-up in the 60 days preceding the event, a more than 50% greater chance of a flare-up 60-120 days before the CV event, but no increased likelihood more than 120 days before the event.

A self-controlled case series based on the same overall cohort with gout yielded similar results while sidestepping any potential for residual confounding, an inherent concern with any case–control analysis, the report notes. It involved 1,421 patients with one or more gout flare and at least one MI or stroke after the diagnosis of gout.

Among that cohort, the CV-event incidence rate ratio, adjusted for age and season of the year, by time interval after a gout flare, was 1.89 (95% confidence interval, 1.54-2.30) at 0-60 days, 1.64 (95% CI, 1.45-1.86) at 61-120 days, and1.29 (95% CI, 1.02-1.64) at 121-180 days.

Also similar, the report noted, were results of several sensitivity analyses, including one that excluded patients with confirmed CVD before their gout diagnosis; another that left out patients at low to moderate CV risk; and one that considered only gout flares treated with colchicine, corticosteroids, or NSAIDs.

The incremental CV event risks observed after flares in the study were small, which “has implications for both cost effectiveness and clinical relevance,” observed Dr. Anderson and Dr. Knowlton.

“An alternative to universal augmentation of cardiovascular risk prevention with therapies among patients with gout flares,” they wrote, would be “to further stratify risk by defining a group at highest near-term risk.” Such interventions could potentially be guided by markers of CV risk such as, for example, levels of high-sensitivity C-reactive protein or lipoprotein(a), or plaque burden on coronary-artery calcium scans.

Dr. Abhishek, Dr. Cipolletta, and the other authors reported no competing interests. Dr. Choi disclosed research support from Ironwood and Horizon; and consulting fees from Ironwood, Selecta, Horizon, Takeda, Kowa, and Vaxart. Dr. Anderson disclosed receiving grants to his institution from Novartis and Milestone.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

There is evidence that gout and heart disease are mechanistically linked by inflammation and patients with gout are at elevated risk for cardiovascular disease (CVD). But do gout flares, on their own, affect short-term risk for CV events? A new analysis based on records from British medical practices suggests that might be the case.

Risk for myocardial infarction or stroke climbed in the weeks after individual gout flare-ups in the study’s more than 60,000 patients with a recent gout diagnosis. The jump in risk, significant but small in absolute terms, held for about 4 months in the case-control study before going away.

A sensitivity analysis that excluded patients who already had CVD when their gout was diagnosed yielded similar results.

The observational study isn’t able to show that gout flares themselves transiently raise the risk for MI or stroke, but it’s enough to send a cautionary message to physicians who care for patients with gout, rheumatologist Abhishek Abhishek, PhD, Nottingham (England) City Hospital, said in an interview.

In such patients who also have conditions like hypertension, diabetes, or dyslipidemia, or a history of heart disease, he said, it’s important “to manage risk factors really aggressively, knowing that when these patients have a gout flare, there’s a temporary increase in risk of a cardiovascular event.”

Managing their absolute CV risk – whether with drug therapy, lifestyle changes, or other interventions – should help limit the transient jump in risk for MI or stroke following a gout flare, proposed Dr. Abhishek, who is senior author on the study published in JAMA, with lead author Edoardo Cipolletta, MD, also from Nottingham City Hospital.

First robust evidence

The case-control study, which involved more than 60,000 patients with a recent gout diagnosis, some who went on to have MI or stroke, looked at rates of such events at different time intervals after gout flares. Those who experienced such events showed a more than 90% increased likelihood of a gout flare-up in the preceding 60 days, a greater than 50% chance of a flare between 60 and 120 days before the event, but no increased likelihood prior to 120 days before the event.

Such a link between gout flares and CV events “has been suspected but never proven,” observed rheumatologist Hyon K. Choi, MD, Harvard Medical School, Boston, who was not associated with the analysis. “This is the first time it has actually been shown in a robust way,” he said in an interview.

The study suggests a “likely causative relationship” between gout flares and CV events, but – as the published report noted – has limitations like any observational study, said Dr. Choi, who also directs the Gout & Crystal Arthropathy Center at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston. “Hopefully, this can be replicated in other cohorts.”

The analysis controlled for a number of relevant potential confounders, he noted, but couldn’t account for all issues that could argue against gout flares as a direct cause of the MIs and strokes.

Gout attacks are a complex experience with a range of potential indirect effects on CV risk, Dr. Choi observed. They can immobilize patients, possibly raising their risk for thrombotic events, for example. They can be exceptionally painful, which causes stress and can lead to frequent or chronic use of glucocorticoids or NSAIDs, all of which can exacerbate high blood pressure and possibly worsen CV risk.

A unique insight

The timing of gout flares relative to acute vascular events hasn’t been fully explored, observed an accompanying editorial. The current study’s “unique insight,” it stated, “is that disease activity from gout was associated with an incremental increase in risk for acute vascular events during the time period immediately following the gout flare.”

Although the study is observational, a “large body of evidence from animal and human research, mechanistic insights, and clinical interventions” support an association between flares and vascular events and “make a causal link eminently reasonable,” stated the editorialists, Jeffrey L. Anderson, MD, and Kirk U. Knowlton, MD, both with Intermountain Medical Center, Salt Lake City, Utah.

The findings, they wrote, “should alert clinicians and patients to the increased cardiovascular risk in the weeks beginning after a gout flare and should focus attention on optimizing preventive measures.” Those can include “lifestyle measures and standard risk-factor control including adherence to diet, statins, anti-inflammatory drugs (e.g., aspirin, colchicine), smoking cessation, diabetic and blood pressure control, and antithrombotic medications as indicated.”

Dr. Choi said the current results argue for more liberal use of colchicine, and for preferring colchicine over other anti-inflammatories, in patients with gout and traditional CV risk factors, given multiple randomized trials supporting the drug’s use in such cases. “If you use colchicine, you are covering their heart disease risk as well as their gout. It’s two birds with one stone.”

Nested case-control study

The investigators accessed electronic health records from 96,153 patients with recently diagnosed gout in England from 1997 to 2020; the cohort’s mean age was about 76 years, and 69% of participants were men. They matched 10,475 patients with at least one CV event to 52,099 others who didn’t have such an event by age, sex, and time from gout diagnosis. In each matched set of patients, those not experiencing a CV event were assigned a flare-to-event interval based on their matching with patients who did experience such an event.

Those with CV events, compared with patients without an event, had a greater than 90% increased likelihood of experiencing a gout flare-up in the 60 days preceding the event, a more than 50% greater chance of a flare-up 60-120 days before the CV event, but no increased likelihood more than 120 days before the event.

A self-controlled case series based on the same overall cohort with gout yielded similar results while sidestepping any potential for residual confounding, an inherent concern with any case–control analysis, the report notes. It involved 1,421 patients with one or more gout flare and at least one MI or stroke after the diagnosis of gout.

Among that cohort, the CV-event incidence rate ratio, adjusted for age and season of the year, by time interval after a gout flare, was 1.89 (95% confidence interval, 1.54-2.30) at 0-60 days, 1.64 (95% CI, 1.45-1.86) at 61-120 days, and1.29 (95% CI, 1.02-1.64) at 121-180 days.

Also similar, the report noted, were results of several sensitivity analyses, including one that excluded patients with confirmed CVD before their gout diagnosis; another that left out patients at low to moderate CV risk; and one that considered only gout flares treated with colchicine, corticosteroids, or NSAIDs.

The incremental CV event risks observed after flares in the study were small, which “has implications for both cost effectiveness and clinical relevance,” observed Dr. Anderson and Dr. Knowlton.

“An alternative to universal augmentation of cardiovascular risk prevention with therapies among patients with gout flares,” they wrote, would be “to further stratify risk by defining a group at highest near-term risk.” Such interventions could potentially be guided by markers of CV risk such as, for example, levels of high-sensitivity C-reactive protein or lipoprotein(a), or plaque burden on coronary-artery calcium scans.

Dr. Abhishek, Dr. Cipolletta, and the other authors reported no competing interests. Dr. Choi disclosed research support from Ironwood and Horizon; and consulting fees from Ironwood, Selecta, Horizon, Takeda, Kowa, and Vaxart. Dr. Anderson disclosed receiving grants to his institution from Novartis and Milestone.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JAMA