User login

COLORADO SPRINGS – Reconsideration of the role of pulmonary hypertension in heart transplant outcomes is appropriate in the emerging era of the use of left ventricular assist devices (LVADs) as bridge to transplant, according to Ann C. Gaffey, MD, of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

“Pulmonary hypertension secondary to congestive heart failure more than likely can be reversed to the values acceptable for heart transplant by the use of an LVAD. For bridge-to-transplant patients, pretransplant pulmonary hypertension does not affect recipient outcomes post transplantation,” she said at the annual meeting of the Western Thoracic Surgical Association.

Vasodilators are prescribed in an effort to reduce PH; however, 40% of patients with PH are unresponsive to the medications and have therefore been excluded from consideration as potential candidates for a donor heart.

But the growing use of LVADs as a bridge to transplant has changed all that, Dr. Gaffey said. As supporting evidence, she presented a retrospective analysis of the United Network for Organ Sharing database on adult heart transplants from mid-2004 through the end of 2014.

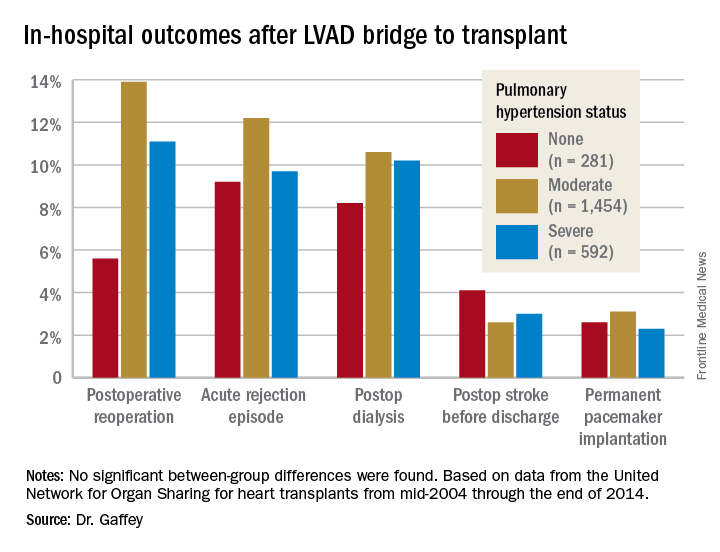

The review turned up 3,951 heart transplant recipients who had been bridged to transplant with an LVAD. Dr. Gaffey and her coinvestigators divided them into three groups: 281 patients without pretransplant PH; 1,454 with moderate PH as defined by 1-3 Wood units; and 592 with severe PH and more than 3 Wood units.

The three groups didn’t differ in terms of age, sex, wait-list time, or the prevalence of diabetes or renal, liver, or cerebrovascular disease. Nor did their donors differ in age, sex, left ventricular function, or allograft ischemic time.

Key in-hospital outcomes were similar between the groups with no, mild, and severe PH.

Moreover, there was no between-group difference in the rate of rejection at 1 year. Five-year survival rates were closely similar in the three groups, in the mid-70s.

Audience member Nahush A. Mokadam, MD, rose to praise Dr. Gaffey’s report.

“This is a great and important study. I think as a group we have been too conservative with pulmonary hypertension, so thank you for shining a good light on it,” said Dr. Mokadam of the University of Washington, Seattle.

Dr. Gaffey reported having no financial conflicts regarding the study, which was conducted free of commercial support.

COLORADO SPRINGS – Reconsideration of the role of pulmonary hypertension in heart transplant outcomes is appropriate in the emerging era of the use of left ventricular assist devices (LVADs) as bridge to transplant, according to Ann C. Gaffey, MD, of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

“Pulmonary hypertension secondary to congestive heart failure more than likely can be reversed to the values acceptable for heart transplant by the use of an LVAD. For bridge-to-transplant patients, pretransplant pulmonary hypertension does not affect recipient outcomes post transplantation,” she said at the annual meeting of the Western Thoracic Surgical Association.

Vasodilators are prescribed in an effort to reduce PH; however, 40% of patients with PH are unresponsive to the medications and have therefore been excluded from consideration as potential candidates for a donor heart.

But the growing use of LVADs as a bridge to transplant has changed all that, Dr. Gaffey said. As supporting evidence, she presented a retrospective analysis of the United Network for Organ Sharing database on adult heart transplants from mid-2004 through the end of 2014.

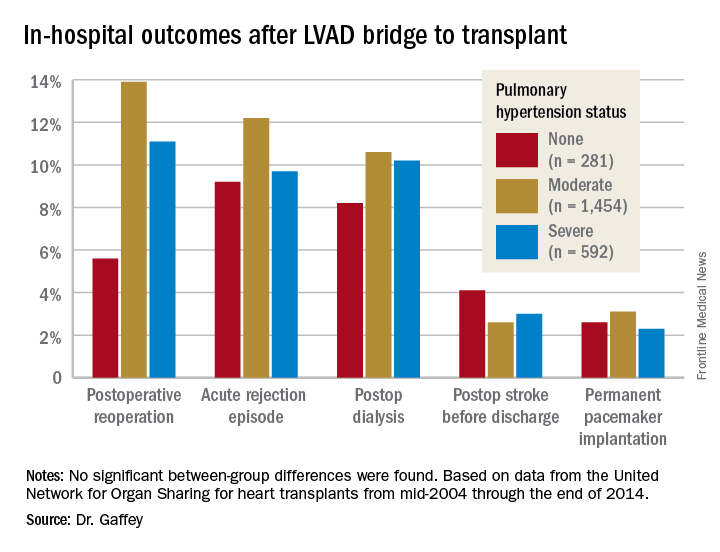

The review turned up 3,951 heart transplant recipients who had been bridged to transplant with an LVAD. Dr. Gaffey and her coinvestigators divided them into three groups: 281 patients without pretransplant PH; 1,454 with moderate PH as defined by 1-3 Wood units; and 592 with severe PH and more than 3 Wood units.

The three groups didn’t differ in terms of age, sex, wait-list time, or the prevalence of diabetes or renal, liver, or cerebrovascular disease. Nor did their donors differ in age, sex, left ventricular function, or allograft ischemic time.

Key in-hospital outcomes were similar between the groups with no, mild, and severe PH.

Moreover, there was no between-group difference in the rate of rejection at 1 year. Five-year survival rates were closely similar in the three groups, in the mid-70s.

Audience member Nahush A. Mokadam, MD, rose to praise Dr. Gaffey’s report.

“This is a great and important study. I think as a group we have been too conservative with pulmonary hypertension, so thank you for shining a good light on it,” said Dr. Mokadam of the University of Washington, Seattle.

Dr. Gaffey reported having no financial conflicts regarding the study, which was conducted free of commercial support.

COLORADO SPRINGS – Reconsideration of the role of pulmonary hypertension in heart transplant outcomes is appropriate in the emerging era of the use of left ventricular assist devices (LVADs) as bridge to transplant, according to Ann C. Gaffey, MD, of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

“Pulmonary hypertension secondary to congestive heart failure more than likely can be reversed to the values acceptable for heart transplant by the use of an LVAD. For bridge-to-transplant patients, pretransplant pulmonary hypertension does not affect recipient outcomes post transplantation,” she said at the annual meeting of the Western Thoracic Surgical Association.

Vasodilators are prescribed in an effort to reduce PH; however, 40% of patients with PH are unresponsive to the medications and have therefore been excluded from consideration as potential candidates for a donor heart.

But the growing use of LVADs as a bridge to transplant has changed all that, Dr. Gaffey said. As supporting evidence, she presented a retrospective analysis of the United Network for Organ Sharing database on adult heart transplants from mid-2004 through the end of 2014.

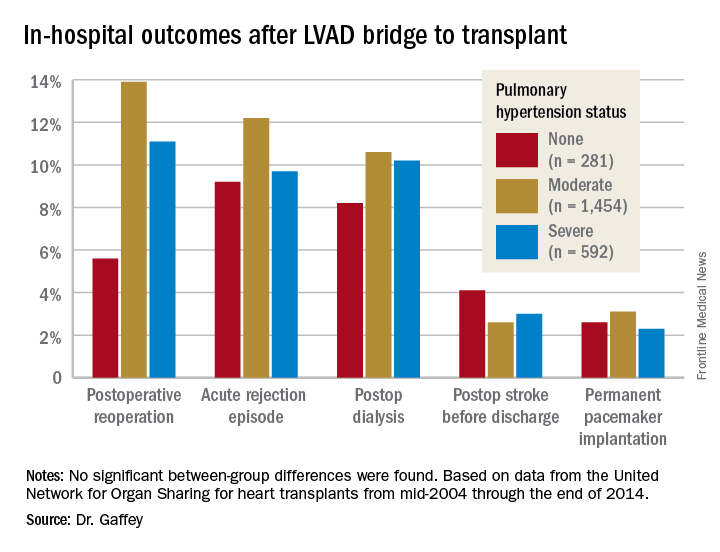

The review turned up 3,951 heart transplant recipients who had been bridged to transplant with an LVAD. Dr. Gaffey and her coinvestigators divided them into three groups: 281 patients without pretransplant PH; 1,454 with moderate PH as defined by 1-3 Wood units; and 592 with severe PH and more than 3 Wood units.

The three groups didn’t differ in terms of age, sex, wait-list time, or the prevalence of diabetes or renal, liver, or cerebrovascular disease. Nor did their donors differ in age, sex, left ventricular function, or allograft ischemic time.

Key in-hospital outcomes were similar between the groups with no, mild, and severe PH.

Moreover, there was no between-group difference in the rate of rejection at 1 year. Five-year survival rates were closely similar in the three groups, in the mid-70s.

Audience member Nahush A. Mokadam, MD, rose to praise Dr. Gaffey’s report.

“This is a great and important study. I think as a group we have been too conservative with pulmonary hypertension, so thank you for shining a good light on it,” said Dr. Mokadam of the University of Washington, Seattle.

Dr. Gaffey reported having no financial conflicts regarding the study, which was conducted free of commercial support.

AT THE WTSA ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point:

Major finding: It’s time to reconsider the practice of excluding patients with pulmonary hypertension from consideration for a donor heart.

Data source: A retrospective analysis of the United Network for Organ Sharing database including outcomes out to 5 years on 3,951 heart transplant recipients who had been bridged to transplant with an LVAD, most of whom had moderate or severe pulmonary hypertension before transplant.

Disclosures: This study was conducted free of commercial support. The presenter reported having no relevant financial conflicts of interest.