User login

How to implement a new model of care

The United States spends one-third of the nation’s health dollars on hospital care, amounting to $1.2 trillion in 2018.1 U.S. hospital beds are prevalent2, and expensive to build and operate, with most hospital services costs related to buildings, equipment, salaried labor, and overhead.3

Despite their mission to heal, hospitals can be harmful, especially for frail and elderly patients. A study completed by the Office of the Inspector General (OIG) found that 13.5% of hospitalized Medicare patients experienced an adverse event that resulted in a prolonged hospital stay, permanent harm, a life-sustaining intervention or death.4 In addition, there is growing concern about acquired post-hospitalization syndrome caused by the physiological stress that patients experience in the hospital, leaving them vulnerable to clinical adverse events such as falls and infections.5

In the mid-1990s, driven by a goal to “avoid the harm of inpatient care and honor the wishes of older adults who refused to go to the hospital”, Dr. Bruce Leff, director of the Center for Transformative Geriatric Research and professor of medicine at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, and his team set out to develop and test Hospital at Home (HaH) – an innovative model for delivering hospital-level care to selected patients in the safety of their homes.

More than 20 years later, despite extensive evidence supporting HaH safety and efficacy, and its successful rollout in other countries, the model has not been widely adopted in the U.S. However, the COVID-19 pandemic amplified interest in HaH by creating an urgent need for flexible hospital bed capacity and heightening concerns about hospital care safety, especially for vulnerable adults.

In this article, we will introduce HaH history and efficacy, and then discuss what it takes to successfully implement HaH.

Hospital at Home: History, efficacy, and early adoption

The earliest HaH study, a 17-patient pilot conducted by Dr. Leff’s team from 1996 to 1998, proved that HaH was feasible, safe, highly satisfactory and cost-effective for selected acutely ill older patients with community-acquired pneumonia, chronic heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or cellulitis.6 In 2000 to 2002, a National Demonstration and Evaluation Study of 455 patients across three sites determined that patients treated in Hospital at Home had statistically significant shorter length of stay (3.2 vs 4.9 days), lower cost ($5,081 vs. $7,480) and complications.7 Equipped with evidence, Dr. Leff and his team focused on HaH dissemination and implementation across several health care systems.8

Presbyterian Healthcare Services in Albuquerque, N.M., was one of the earliest adopters of HaH and launched the program in 2008. The integrated system serves one-third of New Mexicans and includes nine hospitals, more than 100 clinics and the state’s largest health plan. According to Nancy Guinn, MD, a medical director of Presbyterian Healthcare at Home, “Innovation is key to survive in a lean environment like New Mexico, which has the lowest percentage of residents with insurance from their employer and a high rate of government payers.”

Presbyterian selected nine diagnoses for HaH focus: congestive heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, community-acquired pneumonia, cellulitis, deep venous thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, complicated urinary tract infection or urosepsis, nausea and vomiting, and dehydration. The HaH care, including physician services, is reimbursed via a partial DRG (diagnosis-related group) payment that was negotiated internally between the health system and Presbyterian Health Plan.

The results demonstrated that, compared to hospitalized patients with similar conditions, patients in HaH had a lower rate of falls (0% vs. .8%), lower mortality (.93% vs. 3.4%), higher satisfaction (mean score 90.7 vs. 83.9) and 19% lower cost.9 According to Dr. Guinn, more recent results showed even larger cost savings of 42%.10 After starting the HaH model, Presbyterian has launched other programs that work closely with HaH to provide a seamless experience for patients. That includes the Complete Care Program, which offers home-based primary, urgent, and acute care to members covered through Presbyterian Health Plan and has a daily census of 600-700 patients.

Another important milestone came in 2014 when Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York was awarded $9.6 million by the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation (CMMI) to test the HaH model during acute illness and for 30 days after admission. A case study of 507 patients enrolled in the program in 2014 through 2017 revealed that HaH patients had statistically significant shorter length of stay (3.2 days vs. 5.5 days), and lower rates of all-cause 30-day hospital readmissions (8.6% vs. 15.6%), 30-day ED revisits (5.8% vs. 11.7%), and SNF admissions (1.7% vs. 10.4%), and were also more likely to rate their hospital care highly (68.8% vs. 45.3%).11

In 2017, using data from their CMMI study, Mount Sinai submitted an application to the Physician-Focused Payment Model Technical Advisory Committee (PTAC) to implement Hospital at Home as an alternative payment model that bundles the acute episode with 30 days of post‐acute transitional care. The PTAC unanimously approved the proposal and submitted their recommendations to the Secretary of Health and Human Services (HHS) to implement HaH as an alternative payment model that included two parts:

1. A bundled payment equal to a percentage of the prospective DRG (diagnosis-related group) payment that would have been paid to a hospital.

2. A performance-based payment (shared savings/losses) based on (a) total spending during the acute care phase and 30 days afterward relative to a target price, and (b) performance on quality measures.12

In June 2018, the HHS secretary announced that he was not approving the proposal as written, citing, among other things, concerns about proposed payment methodology and patient safety.13

Hospital at Home: Present state

Despite additional evidence of HaH’s impact on lowering cost, decreasing 30-day readmissions, improving patient satisfaction and functional outcomes without an adverse effect on mortality,14, 15 the model has not been widely adopted, largely due to lack of fee-for-service reimbursement from the public payers (Medicare and Medicaid) and complex logistics to implement it.

However, the COVID-19 pandemic created an urgent need for flexible hospital bed capacity and amplified concerns about hospital care safety for vulnerable populations. In response, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) introduced its Hospitals without Walls initiative that allowed hospitals to provide services in other health care facilities and sites that are not part of the existing hospital.16 On November 25, 2020, CMS announced expansion of the Hospital without Walls initiatives to include a Hospital Care at Home program that allows eligible hospitals to treat eligible patients at home.17

With significant evidence supporting HaH’s safety and efficacy, and long overdue support from CMS, it’s now a matter of how to successfully implement it. Let’s explore what it takes to select and enroll patients, deliver acute care at home, and ensure a smooth post-acute transition within the HaH model.

Successfully implementing Hospital at Home

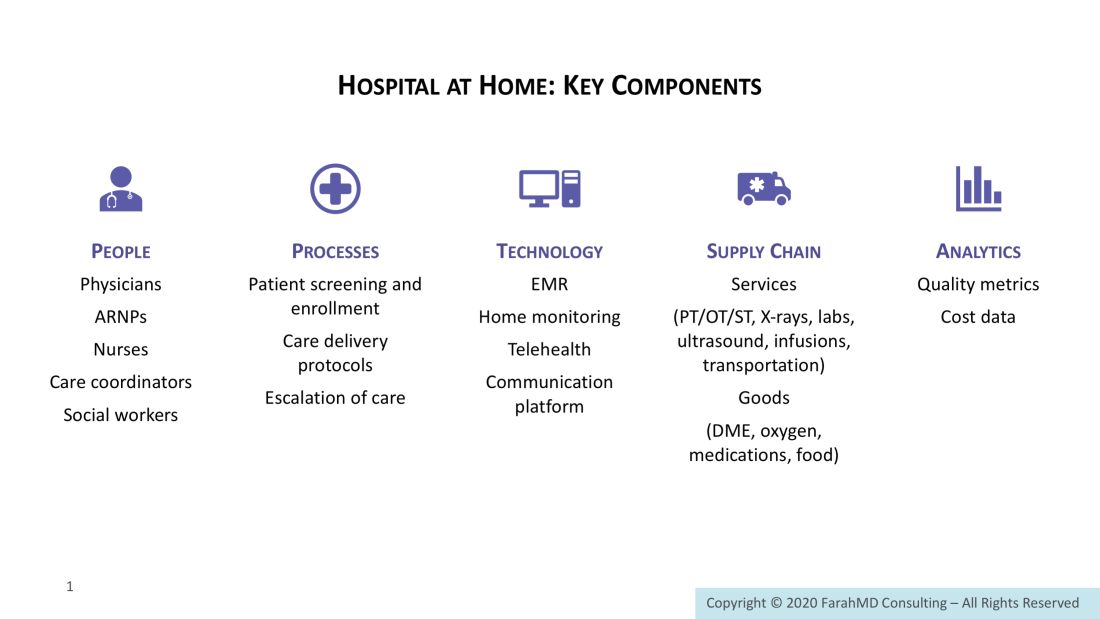

HaH implementation requires five key components – people, processes, technology, supply chain, and analytics – to select and enroll patients, deliver acute care at home, and ensure a smooth postacute transition. Let’s discuss each of them in more detail below.

Selecting and enrolling patients

Patients eligible for HaH are identified based on their insurance, as well as clinical and social criteria. Despite a lack of public payer support, several commercial payers embraced the model for selected patients who consented to receive acute hospital care at home. The patients must meet criteria for an inpatient admission, be medically stable and have a low level of diagnostic uncertainty. Advances in home monitoring technology expanded clinical criteria to include acutely ill patients with multiple comorbidities, including cancer. It is important that patients reside in a safe home environment and live within a reasonable distance from the hospital.

CareMore Health, an integrated health care delivery system serving more than 180,000 Medicare Advantage and Medicaid patients across nine states and Washington D.C., launched Hospital at Home in December 2018, and rapidly scaled from a few referrals to averaging more than 20 new patients per week.

Sashidaran Moodley, MD, medical director at CareMore Health and Aspire Health, in Cerritos, Calif., shared a valuable lesson regarding launching the program: “Do not presume that if you build it, they will come. This is a new model of care that requires physicians to change their behavior and health systems to modify their traditional admission work flows. Program designers should not limit their thinking around sourcing patients just from the emergency department.”

Dr. Moodley recommends moving upstream and bring awareness to the program to drive additional referrals from primary care providers, case managers, and remote patient monitoring programs (for example, heart failure).

Linda DeCherrie, MD, clinical director of Mount Sinai at Home, based in New York, says that “educating and involving hospitalists is key.” At Mount Sinai, patients eligible for HaH are initially evaluated by hospitalists in the ED who write initial orders and then transfer care to HaH hospitalists.

HaH also can enroll eligible patients who still require hospital-level care to complete the last few days of acute hospitalization at home. Early discharge programs have been implemented at CareMore, Presbyterian Healthcare Services in Albuquerque, N.M., and Mount Sinai. At Mount Sinai, a program called Completing Hospitalization at Home initially started with non-COVID patients and expanded to include COVID-19 early discharges, helping to free up much-needed hospital beds.

Delivering acute care at home

HaH requires a well-coordinated multidisciplinary team. Patient care is directed by a team of physicians and nurse practitioners who provide daily in-person or virtual visits. To enable provider work flow, an ambulatory version of electronic medical records (for example, Epic) must be customized to include specialized order sets that mimic inpatient orders and diagnoses-specific care delivery protocols. HaH physicians and nurse practitioners are available 24/7 to address acute patient issues.

In addition, patients receive at least daily visits from registered nurses (RNs) who carry out orders, administer medications, draw labs, and provide clinical assessment and patient education. Some organizations employ HaH nurses, while others contract with home health agencies.

Typically, patients are provided with a tablet to enable telehealth visits, as well as a blood pressure monitor, thermometer, pulse oximeter, and, if needed, scale and glucometer, that allow on-demand or continuous remote monitoring. Recent technology advances in home monitoring enhanced HaH’s capability to care for complex, high-acuity patients, and increased the potential volume of patients that can be safely treated at home.

Providence St. Joseph Health, a not-for-profit health care system operating 51 hospitals and 1,085 clinics across seven states, launched their HaH program earlier this year. Per Danielsson, MD, executive medical director for hospital medicine at Swedish Medical Center in Seattle, describes it as a “high-touch, high-tech program anchored by hospitalists.” The Providence HaH team utilizes a wearable medical device for patients that enables at-home continuous monitoring of vital signs such as temperature, blood pressure, heart rate, respirations, and pulse oximetry. Single-lead EKG monitoring is available for selected patients. Individual patient data is transmitted to a central command center, where a team of nurses and physicians remotely monitor HaH patients. According to Todd Czartoski, MD, chief medical technology officer at Providence, “Hospital at Home improves quality and access, and can substitute for 20%-30% of hospital admissions.”

In addition to patient monitoring and 24/7 provider access, some HaH programs partner with community paramedics for emergency responses. At Mount Sinai, HaH providers can trigger paramedic response, if needed. Paramedics can set up a video link with a doctor and, under the direction of a physician, will provide treatment at home or transport patients to the hospital.

HaH would be impossible without a partnership with local ancillary service providers that can promptly deliver services and goods to patient homes. Raphael Rakowski, CEO of Medically Home, a Boston-based company that partners with health care providers to build virtual hospitals at home, calls it an “acute rapid response supply chain.” The services, both clinical and nonclinical, consist of infusions; x-rays; bedside ultrasound; laboratory; transportation; and skilled physical, occupational, and speech therapy. If patients require services that are not available at home (for example, a CT scan), patients can be transported to and from a diagnostic center. Medical and nonmedical goods include medications, oxygen, durable medical equipment, and even meals.

Delivery of hospital-level services at home requires a seamless coordination between clinical teams and suppliers that relies on nursing care coordinators and supporting nonclinical staff, and is enabled by a secure text messaging platform to communicate within the care team, with suppliers, and with other providers (for example, primary care providers and specialists).

Ensuring smooth postacute transition

Thirty days after hospital discharge is the most critical period, especially for elderly patients. According to one study, 19% of patients experienced adverse events within 3 weeks after hospital discharge.18 Adverse drug events were the most common postdischarge complication, followed by procedural complications and hospital-acquired infections. Furthermore, 30-day all-cause hospital readmissions is a common occurrence. Per the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project database, 17.1% of Medicare and 13.9% of all-payers patients were readmitted to the hospital within 30 days in 2016.19

It is not surprising that some organizations offer ongoing home care during the postacute period. At Mount Sinai, patients discharged from HaH continue to have access to the HaH team around the clock for 30 days to address emergencies and health concerns. Recovery Care Coordinators and social workers monitor patient health status, develop a follow-up plan, coordinate care, and answer questions. Medically Home provides 24/7 care to HaH patients for the entire duration of the acute care episode (34 days) to ensure maximum access to care and no gaps in care and communication. At Presbyterian, most HaH patients are transitioned into a Home Health episode of care to ensure continued high-quality care.

In addition to people, processes, technology, and the supply chain, HaH implementation requires capabilities to collect and analyze quality and cost data to measure program efficacy and, in some arrangements with payers, to reconcile clams data to determine shared savings or losses.

Partnering with third parties

Considering the resources and capabilities required for HaH program development and implementation, it is not surprising that health care providers are choosing to partner with third parties. For example, Mount Sinai partnered with Contessa Health, a Nashville, Tenn.–based company that offers hospitals a turn-key Home Recovery Care program, to assist with supply chain contracting and management, and claims data reconciliation.

Medically Home has partnered with seven health care systems, including the Mayo Clinic, Tufts Medical Center in Boston, and Adventist Health in southern California, to create virtual beds, and is expected to launch the program with 15 health care systems by the end of 2020.

Medically Home offers the following services to its partners to enable care for high-acuity patients at home:

- Assistance with hiring and training of clinical staff.

- Proprietary EMR-integrated orders, notes, and clinical protocols.

- Technology for patient monitoring by the 24/7 central command center; tablets that provide health status updates and daily schedules, and enable televisits; a video platform for video communication; and secure texting.

- Selection, contracting and monitoring the performance of supply chain vendors.

- Analytics.

The future of Hospital at Home

There is no question that HaH can offer a safe, high-quality, and lower-cost alternative to hospitalizations for select patients, which is aligned with the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services’ triple aim of better care for individuals, better health for populations, and lower cost.20

The future of HaH depends on development of a common payment model that will be adopted beyond the pandemic by government and commercial payers. Current payment models vary and include capitated agreements, discounted diagnosis-related group payments for the acute episode, and discounted DRG payments plus shared losses or savings.

The COVID-19 pandemic has created, arguably, the biggest crisis that U.S. health care has ever experienced, and it is far from over. Short term, Hospital at Home offers a solution to create flexible hospital bed capacity and deliver safe hospital-level care for vulnerable populations. Long term, it may be the solution that helps achieve better care for individuals, better health for populations and lower health care costs.

Dr. Farah is a hospitalist, physician advisor, and Lean Six Sigma Black Belt. She is a performance improvement consultant based in Corvallis, Ore., and a member of the Hospitalist’s editorial advisory board.

References

1. Source: www.cms.gov/files/document/nations-health-dollar-where-it-came-where-it-went.pdf

2. Source: www.aha.org/statistics/fast-facts-us-hospitals

3. Roberts RR, et al. Distribution of variable vs fixed costs of hospital care. JAMA. 1999 Feb;281(7):644-9.

4. Levinson DR; US Department of Health and Human Services; HHS; Office of the Inspector General; OIG.

5. Krumholz HM. Post-Hospital Syndrome – An Acquired, Transient Condition of Generalized Risk. N Engl J Med. 2013 Jan;368:100-102.

6. Leff B, et al. Home hospital program: a pilot study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1999 Jun;47(6):697-702.

7. Leff B, et al. Hospital at home: Feasibility and outcomes of a program to provide hospital-level care at home for acutely ill older patients. Ann Intern Med. 2005 Dec;143(11):798-808.

8. Source: www.johnshopkinssolutions.com/solution/hospital-at-home/

9. Cryer L, et al. Costs for ‘Hospital at Home’ Patients Were 19 Percent Lower, with Equal or Better Outcomes Compared to Similar Inpatients. Health Affairs. 2012 Jun;31(6):1237–43.

10. Personal communication with Presbyterian Health Services. May 20, 2020.

11. Federman A, et al. Association of a bundled hospital-at-home and 30-day postacute transitional care program with clinical outcomes and patient experiences. JAMA Intern Med. 2018 Aug;178(8):1033–40.

12. Source: aspe.hhs.gov/system/files/pdf/255906/MtSinaiHAHReportSecretary.pdf

13. Source: aspe.hhs.gov/system/files/pdf/255906/Secretarial_Responses_June_13_2018.508.pdf

14. Shepperd S, et al. Admission avoidance hospital at home. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;9(9):CD007491. DOI:10.1002/14651858.CD007491.pub2.

15. Levine DM, et al. Hospital-level care at home for acutely ill adults: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2020 Jan;172(2);77-85.

16. Source: www.cms.gov/files/document/covid-hospitals.pdf

17. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. CMS Announces Comprehensive Strategy to Enhance Hospital Capacity Amid COVID-19 Surge. 2020 Nov 20.

18. Forster AJ et al. The incidence and severity of adverse events affecting patients after discharge from the hospital. Ann Intern Med. 2003 Mar;138(3):161-7. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-138-3-200302040-00007.

19. Bailey MK et al. Characteristics of 30-Day All-Cause Hospital Readmissions, 2010-2016. Statistical Brief 248. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. 2019 Feb 12. https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb248-Hospital-Readmissions-2010-2016.jsp.

20. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. What are the value-based programs? 2020 Jan 6. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/Value-Based-Programs/Value-Based-Programs.

How to implement a new model of care

How to implement a new model of care

The United States spends one-third of the nation’s health dollars on hospital care, amounting to $1.2 trillion in 2018.1 U.S. hospital beds are prevalent2, and expensive to build and operate, with most hospital services costs related to buildings, equipment, salaried labor, and overhead.3

Despite their mission to heal, hospitals can be harmful, especially for frail and elderly patients. A study completed by the Office of the Inspector General (OIG) found that 13.5% of hospitalized Medicare patients experienced an adverse event that resulted in a prolonged hospital stay, permanent harm, a life-sustaining intervention or death.4 In addition, there is growing concern about acquired post-hospitalization syndrome caused by the physiological stress that patients experience in the hospital, leaving them vulnerable to clinical adverse events such as falls and infections.5

In the mid-1990s, driven by a goal to “avoid the harm of inpatient care and honor the wishes of older adults who refused to go to the hospital”, Dr. Bruce Leff, director of the Center for Transformative Geriatric Research and professor of medicine at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, and his team set out to develop and test Hospital at Home (HaH) – an innovative model for delivering hospital-level care to selected patients in the safety of their homes.

More than 20 years later, despite extensive evidence supporting HaH safety and efficacy, and its successful rollout in other countries, the model has not been widely adopted in the U.S. However, the COVID-19 pandemic amplified interest in HaH by creating an urgent need for flexible hospital bed capacity and heightening concerns about hospital care safety, especially for vulnerable adults.

In this article, we will introduce HaH history and efficacy, and then discuss what it takes to successfully implement HaH.

Hospital at Home: History, efficacy, and early adoption

The earliest HaH study, a 17-patient pilot conducted by Dr. Leff’s team from 1996 to 1998, proved that HaH was feasible, safe, highly satisfactory and cost-effective for selected acutely ill older patients with community-acquired pneumonia, chronic heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or cellulitis.6 In 2000 to 2002, a National Demonstration and Evaluation Study of 455 patients across three sites determined that patients treated in Hospital at Home had statistically significant shorter length of stay (3.2 vs 4.9 days), lower cost ($5,081 vs. $7,480) and complications.7 Equipped with evidence, Dr. Leff and his team focused on HaH dissemination and implementation across several health care systems.8

Presbyterian Healthcare Services in Albuquerque, N.M., was one of the earliest adopters of HaH and launched the program in 2008. The integrated system serves one-third of New Mexicans and includes nine hospitals, more than 100 clinics and the state’s largest health plan. According to Nancy Guinn, MD, a medical director of Presbyterian Healthcare at Home, “Innovation is key to survive in a lean environment like New Mexico, which has the lowest percentage of residents with insurance from their employer and a high rate of government payers.”

Presbyterian selected nine diagnoses for HaH focus: congestive heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, community-acquired pneumonia, cellulitis, deep venous thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, complicated urinary tract infection or urosepsis, nausea and vomiting, and dehydration. The HaH care, including physician services, is reimbursed via a partial DRG (diagnosis-related group) payment that was negotiated internally between the health system and Presbyterian Health Plan.

The results demonstrated that, compared to hospitalized patients with similar conditions, patients in HaH had a lower rate of falls (0% vs. .8%), lower mortality (.93% vs. 3.4%), higher satisfaction (mean score 90.7 vs. 83.9) and 19% lower cost.9 According to Dr. Guinn, more recent results showed even larger cost savings of 42%.10 After starting the HaH model, Presbyterian has launched other programs that work closely with HaH to provide a seamless experience for patients. That includes the Complete Care Program, which offers home-based primary, urgent, and acute care to members covered through Presbyterian Health Plan and has a daily census of 600-700 patients.

Another important milestone came in 2014 when Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York was awarded $9.6 million by the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation (CMMI) to test the HaH model during acute illness and for 30 days after admission. A case study of 507 patients enrolled in the program in 2014 through 2017 revealed that HaH patients had statistically significant shorter length of stay (3.2 days vs. 5.5 days), and lower rates of all-cause 30-day hospital readmissions (8.6% vs. 15.6%), 30-day ED revisits (5.8% vs. 11.7%), and SNF admissions (1.7% vs. 10.4%), and were also more likely to rate their hospital care highly (68.8% vs. 45.3%).11

In 2017, using data from their CMMI study, Mount Sinai submitted an application to the Physician-Focused Payment Model Technical Advisory Committee (PTAC) to implement Hospital at Home as an alternative payment model that bundles the acute episode with 30 days of post‐acute transitional care. The PTAC unanimously approved the proposal and submitted their recommendations to the Secretary of Health and Human Services (HHS) to implement HaH as an alternative payment model that included two parts:

1. A bundled payment equal to a percentage of the prospective DRG (diagnosis-related group) payment that would have been paid to a hospital.

2. A performance-based payment (shared savings/losses) based on (a) total spending during the acute care phase and 30 days afterward relative to a target price, and (b) performance on quality measures.12

In June 2018, the HHS secretary announced that he was not approving the proposal as written, citing, among other things, concerns about proposed payment methodology and patient safety.13

Hospital at Home: Present state

Despite additional evidence of HaH’s impact on lowering cost, decreasing 30-day readmissions, improving patient satisfaction and functional outcomes without an adverse effect on mortality,14, 15 the model has not been widely adopted, largely due to lack of fee-for-service reimbursement from the public payers (Medicare and Medicaid) and complex logistics to implement it.

However, the COVID-19 pandemic created an urgent need for flexible hospital bed capacity and amplified concerns about hospital care safety for vulnerable populations. In response, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) introduced its Hospitals without Walls initiative that allowed hospitals to provide services in other health care facilities and sites that are not part of the existing hospital.16 On November 25, 2020, CMS announced expansion of the Hospital without Walls initiatives to include a Hospital Care at Home program that allows eligible hospitals to treat eligible patients at home.17

With significant evidence supporting HaH’s safety and efficacy, and long overdue support from CMS, it’s now a matter of how to successfully implement it. Let’s explore what it takes to select and enroll patients, deliver acute care at home, and ensure a smooth post-acute transition within the HaH model.

Successfully implementing Hospital at Home

HaH implementation requires five key components – people, processes, technology, supply chain, and analytics – to select and enroll patients, deliver acute care at home, and ensure a smooth postacute transition. Let’s discuss each of them in more detail below.

Selecting and enrolling patients

Patients eligible for HaH are identified based on their insurance, as well as clinical and social criteria. Despite a lack of public payer support, several commercial payers embraced the model for selected patients who consented to receive acute hospital care at home. The patients must meet criteria for an inpatient admission, be medically stable and have a low level of diagnostic uncertainty. Advances in home monitoring technology expanded clinical criteria to include acutely ill patients with multiple comorbidities, including cancer. It is important that patients reside in a safe home environment and live within a reasonable distance from the hospital.

CareMore Health, an integrated health care delivery system serving more than 180,000 Medicare Advantage and Medicaid patients across nine states and Washington D.C., launched Hospital at Home in December 2018, and rapidly scaled from a few referrals to averaging more than 20 new patients per week.

Sashidaran Moodley, MD, medical director at CareMore Health and Aspire Health, in Cerritos, Calif., shared a valuable lesson regarding launching the program: “Do not presume that if you build it, they will come. This is a new model of care that requires physicians to change their behavior and health systems to modify their traditional admission work flows. Program designers should not limit their thinking around sourcing patients just from the emergency department.”

Dr. Moodley recommends moving upstream and bring awareness to the program to drive additional referrals from primary care providers, case managers, and remote patient monitoring programs (for example, heart failure).

Linda DeCherrie, MD, clinical director of Mount Sinai at Home, based in New York, says that “educating and involving hospitalists is key.” At Mount Sinai, patients eligible for HaH are initially evaluated by hospitalists in the ED who write initial orders and then transfer care to HaH hospitalists.

HaH also can enroll eligible patients who still require hospital-level care to complete the last few days of acute hospitalization at home. Early discharge programs have been implemented at CareMore, Presbyterian Healthcare Services in Albuquerque, N.M., and Mount Sinai. At Mount Sinai, a program called Completing Hospitalization at Home initially started with non-COVID patients and expanded to include COVID-19 early discharges, helping to free up much-needed hospital beds.

Delivering acute care at home

HaH requires a well-coordinated multidisciplinary team. Patient care is directed by a team of physicians and nurse practitioners who provide daily in-person or virtual visits. To enable provider work flow, an ambulatory version of electronic medical records (for example, Epic) must be customized to include specialized order sets that mimic inpatient orders and diagnoses-specific care delivery protocols. HaH physicians and nurse practitioners are available 24/7 to address acute patient issues.

In addition, patients receive at least daily visits from registered nurses (RNs) who carry out orders, administer medications, draw labs, and provide clinical assessment and patient education. Some organizations employ HaH nurses, while others contract with home health agencies.

Typically, patients are provided with a tablet to enable telehealth visits, as well as a blood pressure monitor, thermometer, pulse oximeter, and, if needed, scale and glucometer, that allow on-demand or continuous remote monitoring. Recent technology advances in home monitoring enhanced HaH’s capability to care for complex, high-acuity patients, and increased the potential volume of patients that can be safely treated at home.

Providence St. Joseph Health, a not-for-profit health care system operating 51 hospitals and 1,085 clinics across seven states, launched their HaH program earlier this year. Per Danielsson, MD, executive medical director for hospital medicine at Swedish Medical Center in Seattle, describes it as a “high-touch, high-tech program anchored by hospitalists.” The Providence HaH team utilizes a wearable medical device for patients that enables at-home continuous monitoring of vital signs such as temperature, blood pressure, heart rate, respirations, and pulse oximetry. Single-lead EKG monitoring is available for selected patients. Individual patient data is transmitted to a central command center, where a team of nurses and physicians remotely monitor HaH patients. According to Todd Czartoski, MD, chief medical technology officer at Providence, “Hospital at Home improves quality and access, and can substitute for 20%-30% of hospital admissions.”

In addition to patient monitoring and 24/7 provider access, some HaH programs partner with community paramedics for emergency responses. At Mount Sinai, HaH providers can trigger paramedic response, if needed. Paramedics can set up a video link with a doctor and, under the direction of a physician, will provide treatment at home or transport patients to the hospital.

HaH would be impossible without a partnership with local ancillary service providers that can promptly deliver services and goods to patient homes. Raphael Rakowski, CEO of Medically Home, a Boston-based company that partners with health care providers to build virtual hospitals at home, calls it an “acute rapid response supply chain.” The services, both clinical and nonclinical, consist of infusions; x-rays; bedside ultrasound; laboratory; transportation; and skilled physical, occupational, and speech therapy. If patients require services that are not available at home (for example, a CT scan), patients can be transported to and from a diagnostic center. Medical and nonmedical goods include medications, oxygen, durable medical equipment, and even meals.

Delivery of hospital-level services at home requires a seamless coordination between clinical teams and suppliers that relies on nursing care coordinators and supporting nonclinical staff, and is enabled by a secure text messaging platform to communicate within the care team, with suppliers, and with other providers (for example, primary care providers and specialists).

Ensuring smooth postacute transition

Thirty days after hospital discharge is the most critical period, especially for elderly patients. According to one study, 19% of patients experienced adverse events within 3 weeks after hospital discharge.18 Adverse drug events were the most common postdischarge complication, followed by procedural complications and hospital-acquired infections. Furthermore, 30-day all-cause hospital readmissions is a common occurrence. Per the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project database, 17.1% of Medicare and 13.9% of all-payers patients were readmitted to the hospital within 30 days in 2016.19

It is not surprising that some organizations offer ongoing home care during the postacute period. At Mount Sinai, patients discharged from HaH continue to have access to the HaH team around the clock for 30 days to address emergencies and health concerns. Recovery Care Coordinators and social workers monitor patient health status, develop a follow-up plan, coordinate care, and answer questions. Medically Home provides 24/7 care to HaH patients for the entire duration of the acute care episode (34 days) to ensure maximum access to care and no gaps in care and communication. At Presbyterian, most HaH patients are transitioned into a Home Health episode of care to ensure continued high-quality care.

In addition to people, processes, technology, and the supply chain, HaH implementation requires capabilities to collect and analyze quality and cost data to measure program efficacy and, in some arrangements with payers, to reconcile clams data to determine shared savings or losses.

Partnering with third parties

Considering the resources and capabilities required for HaH program development and implementation, it is not surprising that health care providers are choosing to partner with third parties. For example, Mount Sinai partnered with Contessa Health, a Nashville, Tenn.–based company that offers hospitals a turn-key Home Recovery Care program, to assist with supply chain contracting and management, and claims data reconciliation.

Medically Home has partnered with seven health care systems, including the Mayo Clinic, Tufts Medical Center in Boston, and Adventist Health in southern California, to create virtual beds, and is expected to launch the program with 15 health care systems by the end of 2020.

Medically Home offers the following services to its partners to enable care for high-acuity patients at home:

- Assistance with hiring and training of clinical staff.

- Proprietary EMR-integrated orders, notes, and clinical protocols.

- Technology for patient monitoring by the 24/7 central command center; tablets that provide health status updates and daily schedules, and enable televisits; a video platform for video communication; and secure texting.

- Selection, contracting and monitoring the performance of supply chain vendors.

- Analytics.

The future of Hospital at Home

There is no question that HaH can offer a safe, high-quality, and lower-cost alternative to hospitalizations for select patients, which is aligned with the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services’ triple aim of better care for individuals, better health for populations, and lower cost.20

The future of HaH depends on development of a common payment model that will be adopted beyond the pandemic by government and commercial payers. Current payment models vary and include capitated agreements, discounted diagnosis-related group payments for the acute episode, and discounted DRG payments plus shared losses or savings.

The COVID-19 pandemic has created, arguably, the biggest crisis that U.S. health care has ever experienced, and it is far from over. Short term, Hospital at Home offers a solution to create flexible hospital bed capacity and deliver safe hospital-level care for vulnerable populations. Long term, it may be the solution that helps achieve better care for individuals, better health for populations and lower health care costs.

Dr. Farah is a hospitalist, physician advisor, and Lean Six Sigma Black Belt. She is a performance improvement consultant based in Corvallis, Ore., and a member of the Hospitalist’s editorial advisory board.

References

1. Source: www.cms.gov/files/document/nations-health-dollar-where-it-came-where-it-went.pdf

2. Source: www.aha.org/statistics/fast-facts-us-hospitals

3. Roberts RR, et al. Distribution of variable vs fixed costs of hospital care. JAMA. 1999 Feb;281(7):644-9.

4. Levinson DR; US Department of Health and Human Services; HHS; Office of the Inspector General; OIG.

5. Krumholz HM. Post-Hospital Syndrome – An Acquired, Transient Condition of Generalized Risk. N Engl J Med. 2013 Jan;368:100-102.

6. Leff B, et al. Home hospital program: a pilot study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1999 Jun;47(6):697-702.

7. Leff B, et al. Hospital at home: Feasibility and outcomes of a program to provide hospital-level care at home for acutely ill older patients. Ann Intern Med. 2005 Dec;143(11):798-808.

8. Source: www.johnshopkinssolutions.com/solution/hospital-at-home/

9. Cryer L, et al. Costs for ‘Hospital at Home’ Patients Were 19 Percent Lower, with Equal or Better Outcomes Compared to Similar Inpatients. Health Affairs. 2012 Jun;31(6):1237–43.

10. Personal communication with Presbyterian Health Services. May 20, 2020.

11. Federman A, et al. Association of a bundled hospital-at-home and 30-day postacute transitional care program with clinical outcomes and patient experiences. JAMA Intern Med. 2018 Aug;178(8):1033–40.

12. Source: aspe.hhs.gov/system/files/pdf/255906/MtSinaiHAHReportSecretary.pdf

13. Source: aspe.hhs.gov/system/files/pdf/255906/Secretarial_Responses_June_13_2018.508.pdf

14. Shepperd S, et al. Admission avoidance hospital at home. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;9(9):CD007491. DOI:10.1002/14651858.CD007491.pub2.

15. Levine DM, et al. Hospital-level care at home for acutely ill adults: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2020 Jan;172(2);77-85.

16. Source: www.cms.gov/files/document/covid-hospitals.pdf

17. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. CMS Announces Comprehensive Strategy to Enhance Hospital Capacity Amid COVID-19 Surge. 2020 Nov 20.

18. Forster AJ et al. The incidence and severity of adverse events affecting patients after discharge from the hospital. Ann Intern Med. 2003 Mar;138(3):161-7. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-138-3-200302040-00007.

19. Bailey MK et al. Characteristics of 30-Day All-Cause Hospital Readmissions, 2010-2016. Statistical Brief 248. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. 2019 Feb 12. https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb248-Hospital-Readmissions-2010-2016.jsp.

20. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. What are the value-based programs? 2020 Jan 6. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/Value-Based-Programs/Value-Based-Programs.

The United States spends one-third of the nation’s health dollars on hospital care, amounting to $1.2 trillion in 2018.1 U.S. hospital beds are prevalent2, and expensive to build and operate, with most hospital services costs related to buildings, equipment, salaried labor, and overhead.3

Despite their mission to heal, hospitals can be harmful, especially for frail and elderly patients. A study completed by the Office of the Inspector General (OIG) found that 13.5% of hospitalized Medicare patients experienced an adverse event that resulted in a prolonged hospital stay, permanent harm, a life-sustaining intervention or death.4 In addition, there is growing concern about acquired post-hospitalization syndrome caused by the physiological stress that patients experience in the hospital, leaving them vulnerable to clinical adverse events such as falls and infections.5

In the mid-1990s, driven by a goal to “avoid the harm of inpatient care and honor the wishes of older adults who refused to go to the hospital”, Dr. Bruce Leff, director of the Center for Transformative Geriatric Research and professor of medicine at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, and his team set out to develop and test Hospital at Home (HaH) – an innovative model for delivering hospital-level care to selected patients in the safety of their homes.

More than 20 years later, despite extensive evidence supporting HaH safety and efficacy, and its successful rollout in other countries, the model has not been widely adopted in the U.S. However, the COVID-19 pandemic amplified interest in HaH by creating an urgent need for flexible hospital bed capacity and heightening concerns about hospital care safety, especially for vulnerable adults.

In this article, we will introduce HaH history and efficacy, and then discuss what it takes to successfully implement HaH.

Hospital at Home: History, efficacy, and early adoption

The earliest HaH study, a 17-patient pilot conducted by Dr. Leff’s team from 1996 to 1998, proved that HaH was feasible, safe, highly satisfactory and cost-effective for selected acutely ill older patients with community-acquired pneumonia, chronic heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or cellulitis.6 In 2000 to 2002, a National Demonstration and Evaluation Study of 455 patients across three sites determined that patients treated in Hospital at Home had statistically significant shorter length of stay (3.2 vs 4.9 days), lower cost ($5,081 vs. $7,480) and complications.7 Equipped with evidence, Dr. Leff and his team focused on HaH dissemination and implementation across several health care systems.8

Presbyterian Healthcare Services in Albuquerque, N.M., was one of the earliest adopters of HaH and launched the program in 2008. The integrated system serves one-third of New Mexicans and includes nine hospitals, more than 100 clinics and the state’s largest health plan. According to Nancy Guinn, MD, a medical director of Presbyterian Healthcare at Home, “Innovation is key to survive in a lean environment like New Mexico, which has the lowest percentage of residents with insurance from their employer and a high rate of government payers.”

Presbyterian selected nine diagnoses for HaH focus: congestive heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, community-acquired pneumonia, cellulitis, deep venous thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, complicated urinary tract infection or urosepsis, nausea and vomiting, and dehydration. The HaH care, including physician services, is reimbursed via a partial DRG (diagnosis-related group) payment that was negotiated internally between the health system and Presbyterian Health Plan.

The results demonstrated that, compared to hospitalized patients with similar conditions, patients in HaH had a lower rate of falls (0% vs. .8%), lower mortality (.93% vs. 3.4%), higher satisfaction (mean score 90.7 vs. 83.9) and 19% lower cost.9 According to Dr. Guinn, more recent results showed even larger cost savings of 42%.10 After starting the HaH model, Presbyterian has launched other programs that work closely with HaH to provide a seamless experience for patients. That includes the Complete Care Program, which offers home-based primary, urgent, and acute care to members covered through Presbyterian Health Plan and has a daily census of 600-700 patients.

Another important milestone came in 2014 when Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York was awarded $9.6 million by the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation (CMMI) to test the HaH model during acute illness and for 30 days after admission. A case study of 507 patients enrolled in the program in 2014 through 2017 revealed that HaH patients had statistically significant shorter length of stay (3.2 days vs. 5.5 days), and lower rates of all-cause 30-day hospital readmissions (8.6% vs. 15.6%), 30-day ED revisits (5.8% vs. 11.7%), and SNF admissions (1.7% vs. 10.4%), and were also more likely to rate their hospital care highly (68.8% vs. 45.3%).11

In 2017, using data from their CMMI study, Mount Sinai submitted an application to the Physician-Focused Payment Model Technical Advisory Committee (PTAC) to implement Hospital at Home as an alternative payment model that bundles the acute episode with 30 days of post‐acute transitional care. The PTAC unanimously approved the proposal and submitted their recommendations to the Secretary of Health and Human Services (HHS) to implement HaH as an alternative payment model that included two parts:

1. A bundled payment equal to a percentage of the prospective DRG (diagnosis-related group) payment that would have been paid to a hospital.

2. A performance-based payment (shared savings/losses) based on (a) total spending during the acute care phase and 30 days afterward relative to a target price, and (b) performance on quality measures.12

In June 2018, the HHS secretary announced that he was not approving the proposal as written, citing, among other things, concerns about proposed payment methodology and patient safety.13

Hospital at Home: Present state

Despite additional evidence of HaH’s impact on lowering cost, decreasing 30-day readmissions, improving patient satisfaction and functional outcomes without an adverse effect on mortality,14, 15 the model has not been widely adopted, largely due to lack of fee-for-service reimbursement from the public payers (Medicare and Medicaid) and complex logistics to implement it.

However, the COVID-19 pandemic created an urgent need for flexible hospital bed capacity and amplified concerns about hospital care safety for vulnerable populations. In response, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) introduced its Hospitals without Walls initiative that allowed hospitals to provide services in other health care facilities and sites that are not part of the existing hospital.16 On November 25, 2020, CMS announced expansion of the Hospital without Walls initiatives to include a Hospital Care at Home program that allows eligible hospitals to treat eligible patients at home.17

With significant evidence supporting HaH’s safety and efficacy, and long overdue support from CMS, it’s now a matter of how to successfully implement it. Let’s explore what it takes to select and enroll patients, deliver acute care at home, and ensure a smooth post-acute transition within the HaH model.

Successfully implementing Hospital at Home

HaH implementation requires five key components – people, processes, technology, supply chain, and analytics – to select and enroll patients, deliver acute care at home, and ensure a smooth postacute transition. Let’s discuss each of them in more detail below.

Selecting and enrolling patients

Patients eligible for HaH are identified based on their insurance, as well as clinical and social criteria. Despite a lack of public payer support, several commercial payers embraced the model for selected patients who consented to receive acute hospital care at home. The patients must meet criteria for an inpatient admission, be medically stable and have a low level of diagnostic uncertainty. Advances in home monitoring technology expanded clinical criteria to include acutely ill patients with multiple comorbidities, including cancer. It is important that patients reside in a safe home environment and live within a reasonable distance from the hospital.

CareMore Health, an integrated health care delivery system serving more than 180,000 Medicare Advantage and Medicaid patients across nine states and Washington D.C., launched Hospital at Home in December 2018, and rapidly scaled from a few referrals to averaging more than 20 new patients per week.

Sashidaran Moodley, MD, medical director at CareMore Health and Aspire Health, in Cerritos, Calif., shared a valuable lesson regarding launching the program: “Do not presume that if you build it, they will come. This is a new model of care that requires physicians to change their behavior and health systems to modify their traditional admission work flows. Program designers should not limit their thinking around sourcing patients just from the emergency department.”

Dr. Moodley recommends moving upstream and bring awareness to the program to drive additional referrals from primary care providers, case managers, and remote patient monitoring programs (for example, heart failure).

Linda DeCherrie, MD, clinical director of Mount Sinai at Home, based in New York, says that “educating and involving hospitalists is key.” At Mount Sinai, patients eligible for HaH are initially evaluated by hospitalists in the ED who write initial orders and then transfer care to HaH hospitalists.

HaH also can enroll eligible patients who still require hospital-level care to complete the last few days of acute hospitalization at home. Early discharge programs have been implemented at CareMore, Presbyterian Healthcare Services in Albuquerque, N.M., and Mount Sinai. At Mount Sinai, a program called Completing Hospitalization at Home initially started with non-COVID patients and expanded to include COVID-19 early discharges, helping to free up much-needed hospital beds.

Delivering acute care at home

HaH requires a well-coordinated multidisciplinary team. Patient care is directed by a team of physicians and nurse practitioners who provide daily in-person or virtual visits. To enable provider work flow, an ambulatory version of electronic medical records (for example, Epic) must be customized to include specialized order sets that mimic inpatient orders and diagnoses-specific care delivery protocols. HaH physicians and nurse practitioners are available 24/7 to address acute patient issues.

In addition, patients receive at least daily visits from registered nurses (RNs) who carry out orders, administer medications, draw labs, and provide clinical assessment and patient education. Some organizations employ HaH nurses, while others contract with home health agencies.

Typically, patients are provided with a tablet to enable telehealth visits, as well as a blood pressure monitor, thermometer, pulse oximeter, and, if needed, scale and glucometer, that allow on-demand or continuous remote monitoring. Recent technology advances in home monitoring enhanced HaH’s capability to care for complex, high-acuity patients, and increased the potential volume of patients that can be safely treated at home.

Providence St. Joseph Health, a not-for-profit health care system operating 51 hospitals and 1,085 clinics across seven states, launched their HaH program earlier this year. Per Danielsson, MD, executive medical director for hospital medicine at Swedish Medical Center in Seattle, describes it as a “high-touch, high-tech program anchored by hospitalists.” The Providence HaH team utilizes a wearable medical device for patients that enables at-home continuous monitoring of vital signs such as temperature, blood pressure, heart rate, respirations, and pulse oximetry. Single-lead EKG monitoring is available for selected patients. Individual patient data is transmitted to a central command center, where a team of nurses and physicians remotely monitor HaH patients. According to Todd Czartoski, MD, chief medical technology officer at Providence, “Hospital at Home improves quality and access, and can substitute for 20%-30% of hospital admissions.”

In addition to patient monitoring and 24/7 provider access, some HaH programs partner with community paramedics for emergency responses. At Mount Sinai, HaH providers can trigger paramedic response, if needed. Paramedics can set up a video link with a doctor and, under the direction of a physician, will provide treatment at home or transport patients to the hospital.

HaH would be impossible without a partnership with local ancillary service providers that can promptly deliver services and goods to patient homes. Raphael Rakowski, CEO of Medically Home, a Boston-based company that partners with health care providers to build virtual hospitals at home, calls it an “acute rapid response supply chain.” The services, both clinical and nonclinical, consist of infusions; x-rays; bedside ultrasound; laboratory; transportation; and skilled physical, occupational, and speech therapy. If patients require services that are not available at home (for example, a CT scan), patients can be transported to and from a diagnostic center. Medical and nonmedical goods include medications, oxygen, durable medical equipment, and even meals.

Delivery of hospital-level services at home requires a seamless coordination between clinical teams and suppliers that relies on nursing care coordinators and supporting nonclinical staff, and is enabled by a secure text messaging platform to communicate within the care team, with suppliers, and with other providers (for example, primary care providers and specialists).

Ensuring smooth postacute transition

Thirty days after hospital discharge is the most critical period, especially for elderly patients. According to one study, 19% of patients experienced adverse events within 3 weeks after hospital discharge.18 Adverse drug events were the most common postdischarge complication, followed by procedural complications and hospital-acquired infections. Furthermore, 30-day all-cause hospital readmissions is a common occurrence. Per the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project database, 17.1% of Medicare and 13.9% of all-payers patients were readmitted to the hospital within 30 days in 2016.19

It is not surprising that some organizations offer ongoing home care during the postacute period. At Mount Sinai, patients discharged from HaH continue to have access to the HaH team around the clock for 30 days to address emergencies and health concerns. Recovery Care Coordinators and social workers monitor patient health status, develop a follow-up plan, coordinate care, and answer questions. Medically Home provides 24/7 care to HaH patients for the entire duration of the acute care episode (34 days) to ensure maximum access to care and no gaps in care and communication. At Presbyterian, most HaH patients are transitioned into a Home Health episode of care to ensure continued high-quality care.

In addition to people, processes, technology, and the supply chain, HaH implementation requires capabilities to collect and analyze quality and cost data to measure program efficacy and, in some arrangements with payers, to reconcile clams data to determine shared savings or losses.

Partnering with third parties

Considering the resources and capabilities required for HaH program development and implementation, it is not surprising that health care providers are choosing to partner with third parties. For example, Mount Sinai partnered with Contessa Health, a Nashville, Tenn.–based company that offers hospitals a turn-key Home Recovery Care program, to assist with supply chain contracting and management, and claims data reconciliation.

Medically Home has partnered with seven health care systems, including the Mayo Clinic, Tufts Medical Center in Boston, and Adventist Health in southern California, to create virtual beds, and is expected to launch the program with 15 health care systems by the end of 2020.

Medically Home offers the following services to its partners to enable care for high-acuity patients at home:

- Assistance with hiring and training of clinical staff.

- Proprietary EMR-integrated orders, notes, and clinical protocols.

- Technology for patient monitoring by the 24/7 central command center; tablets that provide health status updates and daily schedules, and enable televisits; a video platform for video communication; and secure texting.

- Selection, contracting and monitoring the performance of supply chain vendors.

- Analytics.

The future of Hospital at Home

There is no question that HaH can offer a safe, high-quality, and lower-cost alternative to hospitalizations for select patients, which is aligned with the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services’ triple aim of better care for individuals, better health for populations, and lower cost.20

The future of HaH depends on development of a common payment model that will be adopted beyond the pandemic by government and commercial payers. Current payment models vary and include capitated agreements, discounted diagnosis-related group payments for the acute episode, and discounted DRG payments plus shared losses or savings.

The COVID-19 pandemic has created, arguably, the biggest crisis that U.S. health care has ever experienced, and it is far from over. Short term, Hospital at Home offers a solution to create flexible hospital bed capacity and deliver safe hospital-level care for vulnerable populations. Long term, it may be the solution that helps achieve better care for individuals, better health for populations and lower health care costs.

Dr. Farah is a hospitalist, physician advisor, and Lean Six Sigma Black Belt. She is a performance improvement consultant based in Corvallis, Ore., and a member of the Hospitalist’s editorial advisory board.

References

1. Source: www.cms.gov/files/document/nations-health-dollar-where-it-came-where-it-went.pdf

2. Source: www.aha.org/statistics/fast-facts-us-hospitals

3. Roberts RR, et al. Distribution of variable vs fixed costs of hospital care. JAMA. 1999 Feb;281(7):644-9.

4. Levinson DR; US Department of Health and Human Services; HHS; Office of the Inspector General; OIG.

5. Krumholz HM. Post-Hospital Syndrome – An Acquired, Transient Condition of Generalized Risk. N Engl J Med. 2013 Jan;368:100-102.

6. Leff B, et al. Home hospital program: a pilot study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1999 Jun;47(6):697-702.

7. Leff B, et al. Hospital at home: Feasibility and outcomes of a program to provide hospital-level care at home for acutely ill older patients. Ann Intern Med. 2005 Dec;143(11):798-808.

8. Source: www.johnshopkinssolutions.com/solution/hospital-at-home/

9. Cryer L, et al. Costs for ‘Hospital at Home’ Patients Were 19 Percent Lower, with Equal or Better Outcomes Compared to Similar Inpatients. Health Affairs. 2012 Jun;31(6):1237–43.

10. Personal communication with Presbyterian Health Services. May 20, 2020.

11. Federman A, et al. Association of a bundled hospital-at-home and 30-day postacute transitional care program with clinical outcomes and patient experiences. JAMA Intern Med. 2018 Aug;178(8):1033–40.

12. Source: aspe.hhs.gov/system/files/pdf/255906/MtSinaiHAHReportSecretary.pdf

13. Source: aspe.hhs.gov/system/files/pdf/255906/Secretarial_Responses_June_13_2018.508.pdf

14. Shepperd S, et al. Admission avoidance hospital at home. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;9(9):CD007491. DOI:10.1002/14651858.CD007491.pub2.

15. Levine DM, et al. Hospital-level care at home for acutely ill adults: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2020 Jan;172(2);77-85.

16. Source: www.cms.gov/files/document/covid-hospitals.pdf

17. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. CMS Announces Comprehensive Strategy to Enhance Hospital Capacity Amid COVID-19 Surge. 2020 Nov 20.

18. Forster AJ et al. The incidence and severity of adverse events affecting patients after discharge from the hospital. Ann Intern Med. 2003 Mar;138(3):161-7. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-138-3-200302040-00007.

19. Bailey MK et al. Characteristics of 30-Day All-Cause Hospital Readmissions, 2010-2016. Statistical Brief 248. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. 2019 Feb 12. https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb248-Hospital-Readmissions-2010-2016.jsp.

20. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. What are the value-based programs? 2020 Jan 6. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/Value-Based-Programs/Value-Based-Programs.