User login

Case

A 79-year-old male with coronary artery disease, hypertension, non-insulin-dependent mellitus, moderate dementia, and chronic renal insufficiency is admitted after a fall evaluation. He is widowed and lives in an assisted living facility. He’s accompanied by his niece, is alert, and oriented to person. He thinks he is in a clinic and is unable to state the year, but the remainder of the examination is unremarkable. His labs are notable for potassium of 6.3 mmol/L, BUN of 78 mg/dL, and Cr of 3.7 mg/dL. The niece reports that the patient is not fond of medical care, thus the most recent labs are from two years ago (and indicate a BUN of 39 and Cr of 2.8, with an upward trend over the past decade). You discuss possible long-term need for dialysis with the patient and niece, and the patient clearly states "no." However, he also states that it is 1988. How do you determine if he has the capacity to make decisions?

Overview

Hospitalists are familiar with the doctrine of informed consent—describing a disease, treatment options, associated risks and benefits, potential for complications, and alternatives, including no treatment. Not only must the patient be informed, and the decision free from any coercion, but the patient also must have capacity to make the decision.

Hospitalists often care for patients in whom decision-making capacity comes into question. This includes populations with depression, psychosis, dementia, stroke, severe personality disorders, developmental delay, comatose patients, as well as those with impaired attentional capacity (e.g. acute pain) or general debility (e.g. metastatic cancer).1,2

ave for the comatose patient, whether the patient has capacity might not be obvious. However, addressing the components of capacity (communication, understanding, appreciation, and rationalization) by using a validated clinical tool, such as the MacCAT-T, or more simply by systematically applying those four components to the clinical scenario under consideration, hospitalists can make this determination.

Review of the Literature

It is important to differentiate capacity from competency. Competency is a global assessment and a legal determination made by a judge in court. Capacity, on the other hand, is a functional assessment regarding a particular decision. Capacity is not static, and it can be performed by any clinician familiar with the patient. A hospitalist often is well positioned to make a capacity determination given established rapport with the patient and familiarity with the details of the case.

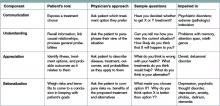

To make this determination, a hospitalist needs to know how to assess capacity. Although capacity usually is defined by state law and varies by jurisdiction, clinicians generally can assume it includes one or more of the four key components:

- Communication. The patient needs to be able to express a treatment choice, and this decision needs to be stable enough for the treatment to be implemented. Changing one’s decision in itself would not bring a patient’s capacity into question, so long as the patient was able to explain the rationale behind the switch. Frequent changes back and forth in the decision-making, however, could be indicative of an underlying psychiatric disorder or extreme indecision, which could bring capacity into question.

- Understanding. The patient needs to recall conversations about treatment, to make the link between causal relationships, and to process probabilities for outcomes. Problems with memory, attention span, and intelligence can affect one’s understanding.

- Appreciation. The patient should be able to identify the illness, treatment options, and likely outcomes as things that will affect him or her directly. A lack of appreciation usually stems from a denial based on intelligence (lack of a capability to understand) or emotion, or a delusion that the patient is not affected by this situation the same way and will have a different outcome.

- Rationalization or reasoning. The patient needs to be able to weigh the risks and benefits of the treatment options presented to come to a conclusion in keeping with their goals and best interests, as defined by their personal set of values. This often is affected in psychosis, depression, anxiety, phobias, delirium, and dementia.3

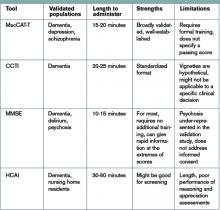

Several clinical capacity tools have been developed to assess these components:

Clinical tools.

The Mini-Mental Status Examination (MMSE) is a bedside test of a patient’s cognitive function, with scores ranging from 0 to 30.4 Although it wasn’t developed for assessing decision-making capacity, it has been compared with expert evaluation for assessment of capacity; the test performs reasonably well, particularly with high and low scores. Specifically, a MMSE >24 has a negative likelihood ratio (LR) of 0.05 for lack of capacity, while a MMSE <16 has a positive LR of 15.5 Scores from 17 to 23 do not correlate well with capacity, and further testing would be necessary. It is easy to administer, requires no formal training, and is familiar to most hospitalists. However, it does not address any specific aspects of informed consent, such as understanding or choice, and has not been validated in patients with mental illness.

The MacArthur Competence Assessment Tools for Treatment (MacCAT-T) is regarded as the gold standard for capacity assessment aids. It utilizes hospital chart review followed by a semi-structured interview to address clinical issues relevant to the patient being assessed; it takes 15 to 20 minutes to complete.6 The test provides scores in each of the four domains (choice, understanding, appreciation, and reasoning) of capacity. It has been validated in patients with dementia, schizophrenia, and depression. Limiting its clinical applicability is the fact that the MacCAT-T requires training to administer and interpret the results, though this is a relatively brief process.

The Capacity to Consent to Treatment Instrument (CCTI) uses hypothetical clinical vignettes in a structured interview to assess capacity across all four domains. The tool was developed and validated in patients with dementia and Parkinson’s disease, and takes 20 to 25 minutes to complete.7 A potential limitation is the CCTI’s use of vignettes as opposed to a patient-specific discussion, which could lead to different patient answers and a false assessment of the patient’s capacity.

The Hopemont Capacity Assessment Interview (HCAI) utilizes hypothetical vignettes in a semi-structured interview format to assess understanding, appreciation, choice, and likely reasoning.8,9 Similar to CCTI, HCAI is not modified for individual patients. Rather, it uses clinical vignettes to gauge a patient’s ability to make decisions. The test takes 30 to 60 minutes to administer and performs less well in assessing appreciation and reasoning than the MacCAT-T and CCTI.10

It is not necessary to perform a formal assessment of capacity on every inpatient. For most, there is no reasonable concern for impaired capacity, obviating the need for formal testing. Likewise, in patients who clearly lack capacity, such as those with end-stage dementia or established guardians, formal reassessment usually is not required. Formal testing is most useful in situations in which capacity is unclear, disagreement amongst surrogate decision-makers exists, or judicial involvement is anticipated.

The MacCAT-T has been validated in the broadest population and is probably the most clinically useful tool currently available. The MMSE is an attractive alternative because of its widespread use and familiarity; however, it is imprecise with scores from 17 to 23, limiting its applicability.

At a minimum, familiarity with the core legal standards of capacity (communication of choice, understanding, appreciation, and reasoning) will improve a hospitalist’s ability to identify patients who lack capacity. Understanding and applying the defined markers most often provides a sufficient capacity evaluation in itself. As capacity is not static, the decision usually requires more than one assessment.

Equally, deciding that a patient lacks capacity is not an end in itself, and the underlying cause should be addressed. Certain factors, such as infection, medication, time of day, and relationship with the clinician doing the assessment, can affect a patient’s capacity. These should be addressed through treatment, education, and social support whenever possible in order to optimize a patient’s performance during the capacity evaluation. If the decision can be delayed until a time when the patient can regain capacity, this should be done in order to maximize the patient’s autonomy.11

Risk-related standards of capacity.

Although some question the notion, given our desire to facilitate management beneficial to the patient, the general consensus is that we have a lower threshold for capacity for consent to treatments that are low-risk and high-benefit.12,13 We would then have a somewhat higher threshold for capacity to refuse that same treatment. Stemming from a desire to protect patients from harm, we have a relatively higher threshold for capacity to make decisions regarding high-risk, low-benefit treatments. For the remainder of cases (low risk/low benefit; high risk/high benefit), as well as treatments that significantly impact a patient’s lifestyle (e.g. dialysis, amputation), we have a low capacity to let patients decide for themselves.11,14

Other considerations.

Clinicians should be thorough in documenting details in coming to a capacity determination, both as a means to formalize the thought process running through the four determinants of capacity, and in order to document for future reference. Cases in which it could be reasonable to call a consultant for those familiar with the assessment basics include:

- Cases in which a determination of lack of capacity could adversely affect the hospitalist’s relationship with the patient;

- Cases in which the hospitalist lacks the time to properly perform the evaluation;

- Particularly difficult or high-stakes cases (e.g. cases that might involve legal proceedings); and

- Cases in which significant mental illness affects a patient’s capacity.11

Early involvement of potential surrogate decision-makers is wise for patients in whom capacity is questioned, both for obtaining collateral history as well as initiating dialogue as to the patient’s wishes. When a patient is found to lack capacity, resources to utilize to help make a treatment decision include existing advance directives and substitute decision-makers, such as durable power of attorneys (DPOAs) and family members. In those rare cases in which clinicians are unable to reach a consensus about a patient’s capacity, an ethics consult should be considered.

Back to the Case.

Following the patient’s declaration that dialysis is not something he is interested in, his niece reports that he is a minimalist when it comes to interventions, and that he had similarly refused a cardiac catheterization in the 1990s. You review with the patient and niece that dialysis would be a procedure to replace his failing kidney function, and that failure to pursue this would ultimately be life-threatening and likely result in death, especially in regard to electrolyte abnormalities and his lack of any other terminal illness.

The consulting nephrologist reviews their recommendations with the patient and niece as well, and the patient consistently refuses. Having clearly communicated his choice, you ask the patient if he understands the situation. He says, "My kidneys are failing. That’s how I got the high potassium." You ask him what that means. "They aren’t going to function on their own much longer," he says. "I could die from it."

You confirm his ideas, and ask him why he doesn’t want dialysis. "I don’t want dialysis because I don’t want to spend my life hooked up to machines three times a week," the patient explains. "I just want to let things run their natural course." The niece says her uncle wouldn’t have wanted dialysis even if it were 10 years ago, so she’s not surprised he is refusing now.

Following this discussion, you feel comfortable that the patient has capacity to make this decision. Having documented this discussion, you discharge him to a subacute rehabilitation facility.

Bottom Line.

In cases in which capacity is in question, a hospitalist’s case-by-case review of the four components of capacity—communicating a choice, understanding, appreciation, and rationalization and reasoning—is warranted to help determine whether a patient has capacity. In cases in which a second opinion is warranted, psychiatry, geriatrics, or ethics consults could be utilized.

Drs. Dastidar and Odden are hospitalists at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor.

References

- Buchanan A, Brock DW. Deciding for others. Milbank Q. 1986;64(Suppl. 2):17-94.

- Guidelines for assessing the decision-making capacities of potential research subjects with cognitive impairment. American Psychiatric Association. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155(11):1649-50.

- Appelbaum PS, Grisso T. Assessing patients’ capacities to consent to treatment. N Engl J Med. 1988;319(25):1635-1638.

- Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189-198.

- Etchells E, Darzins P, Silberfeld M, et al. Assessment of patient capacity to consent to treatment. J Gen Intern Med. 1999;14:27-34.

- Grisso T, Appelbaum PS, Hill-Fotouhi C. The MacCAT-T: a clinical tool to assess patients’ capacities to make treatment decisions. Psychiatr Serv. 1997;48:1415- 1419.

- Marson DC, Ingram KK, Cody HA, Harrell LE. Assessing the competency of patients with Alzheimer’s disease under different legal standards. A prototype instrument. Arch Neurol. 1995;52:949-954.

- Edelstein B. Hopemont Capacity Assessment Interview Manual and Scoring Guide. 1999: Morgantown, W.V.: West Virginia University.

- Pruchno RA, Smyer MA, Rose MS, Hartman-Stein PE, Henderson-Laribee DL. Competence of long-term care residents to participate in decisions about their medical care: a brief, objective assessment. Gerontologist. 1995;35:622-629.

- Moye J, Karel M, Azar AR, Gurrera R. Capacity to consent to treatment: empirical comparison of three instruments in older adults with and without dementia. Gerontologist. 2004;44:166-175.

- Grisso T, Appelbaum PS. Assessing competence to consent to treatment: a guide for physicians and other health professionals. 1998; New York: Oxford University Press, 211.

- Cale GS. Risk-related standards of competence: continuing the debate over risk-related standards of competence. Bioethics. 1999;13(2):131-148.

- Checkland D. On risk and decisional capacity. J Med Philos. 2001;26(1):35-59.

- Wilks I. The debate over risk-related standards of competence. Bioethics. 1997;11(5):413-426.

- Ganzini L, Volicer L, Nelson WA, Fox E, Derse AR. Ten myths about decision-making capacity. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2004;5(4):263-267.

Acknowledgements:The authors would like to thank Dr. Jeff Rohde for reviewing a copy of the manuscript, and Dr. Amy Rosinski for providing direction from the psychiatry standpoint

Case

A 79-year-old male with coronary artery disease, hypertension, non-insulin-dependent mellitus, moderate dementia, and chronic renal insufficiency is admitted after a fall evaluation. He is widowed and lives in an assisted living facility. He’s accompanied by his niece, is alert, and oriented to person. He thinks he is in a clinic and is unable to state the year, but the remainder of the examination is unremarkable. His labs are notable for potassium of 6.3 mmol/L, BUN of 78 mg/dL, and Cr of 3.7 mg/dL. The niece reports that the patient is not fond of medical care, thus the most recent labs are from two years ago (and indicate a BUN of 39 and Cr of 2.8, with an upward trend over the past decade). You discuss possible long-term need for dialysis with the patient and niece, and the patient clearly states "no." However, he also states that it is 1988. How do you determine if he has the capacity to make decisions?

Overview

Hospitalists are familiar with the doctrine of informed consent—describing a disease, treatment options, associated risks and benefits, potential for complications, and alternatives, including no treatment. Not only must the patient be informed, and the decision free from any coercion, but the patient also must have capacity to make the decision.

Hospitalists often care for patients in whom decision-making capacity comes into question. This includes populations with depression, psychosis, dementia, stroke, severe personality disorders, developmental delay, comatose patients, as well as those with impaired attentional capacity (e.g. acute pain) or general debility (e.g. metastatic cancer).1,2

ave for the comatose patient, whether the patient has capacity might not be obvious. However, addressing the components of capacity (communication, understanding, appreciation, and rationalization) by using a validated clinical tool, such as the MacCAT-T, or more simply by systematically applying those four components to the clinical scenario under consideration, hospitalists can make this determination.

Review of the Literature

It is important to differentiate capacity from competency. Competency is a global assessment and a legal determination made by a judge in court. Capacity, on the other hand, is a functional assessment regarding a particular decision. Capacity is not static, and it can be performed by any clinician familiar with the patient. A hospitalist often is well positioned to make a capacity determination given established rapport with the patient and familiarity with the details of the case.

To make this determination, a hospitalist needs to know how to assess capacity. Although capacity usually is defined by state law and varies by jurisdiction, clinicians generally can assume it includes one or more of the four key components:

- Communication. The patient needs to be able to express a treatment choice, and this decision needs to be stable enough for the treatment to be implemented. Changing one’s decision in itself would not bring a patient’s capacity into question, so long as the patient was able to explain the rationale behind the switch. Frequent changes back and forth in the decision-making, however, could be indicative of an underlying psychiatric disorder or extreme indecision, which could bring capacity into question.

- Understanding. The patient needs to recall conversations about treatment, to make the link between causal relationships, and to process probabilities for outcomes. Problems with memory, attention span, and intelligence can affect one’s understanding.

- Appreciation. The patient should be able to identify the illness, treatment options, and likely outcomes as things that will affect him or her directly. A lack of appreciation usually stems from a denial based on intelligence (lack of a capability to understand) or emotion, or a delusion that the patient is not affected by this situation the same way and will have a different outcome.

- Rationalization or reasoning. The patient needs to be able to weigh the risks and benefits of the treatment options presented to come to a conclusion in keeping with their goals and best interests, as defined by their personal set of values. This often is affected in psychosis, depression, anxiety, phobias, delirium, and dementia.3

Several clinical capacity tools have been developed to assess these components:

Clinical tools.

The Mini-Mental Status Examination (MMSE) is a bedside test of a patient’s cognitive function, with scores ranging from 0 to 30.4 Although it wasn’t developed for assessing decision-making capacity, it has been compared with expert evaluation for assessment of capacity; the test performs reasonably well, particularly with high and low scores. Specifically, a MMSE >24 has a negative likelihood ratio (LR) of 0.05 for lack of capacity, while a MMSE <16 has a positive LR of 15.5 Scores from 17 to 23 do not correlate well with capacity, and further testing would be necessary. It is easy to administer, requires no formal training, and is familiar to most hospitalists. However, it does not address any specific aspects of informed consent, such as understanding or choice, and has not been validated in patients with mental illness.

The MacArthur Competence Assessment Tools for Treatment (MacCAT-T) is regarded as the gold standard for capacity assessment aids. It utilizes hospital chart review followed by a semi-structured interview to address clinical issues relevant to the patient being assessed; it takes 15 to 20 minutes to complete.6 The test provides scores in each of the four domains (choice, understanding, appreciation, and reasoning) of capacity. It has been validated in patients with dementia, schizophrenia, and depression. Limiting its clinical applicability is the fact that the MacCAT-T requires training to administer and interpret the results, though this is a relatively brief process.

The Capacity to Consent to Treatment Instrument (CCTI) uses hypothetical clinical vignettes in a structured interview to assess capacity across all four domains. The tool was developed and validated in patients with dementia and Parkinson’s disease, and takes 20 to 25 minutes to complete.7 A potential limitation is the CCTI’s use of vignettes as opposed to a patient-specific discussion, which could lead to different patient answers and a false assessment of the patient’s capacity.

The Hopemont Capacity Assessment Interview (HCAI) utilizes hypothetical vignettes in a semi-structured interview format to assess understanding, appreciation, choice, and likely reasoning.8,9 Similar to CCTI, HCAI is not modified for individual patients. Rather, it uses clinical vignettes to gauge a patient’s ability to make decisions. The test takes 30 to 60 minutes to administer and performs less well in assessing appreciation and reasoning than the MacCAT-T and CCTI.10

It is not necessary to perform a formal assessment of capacity on every inpatient. For most, there is no reasonable concern for impaired capacity, obviating the need for formal testing. Likewise, in patients who clearly lack capacity, such as those with end-stage dementia or established guardians, formal reassessment usually is not required. Formal testing is most useful in situations in which capacity is unclear, disagreement amongst surrogate decision-makers exists, or judicial involvement is anticipated.

The MacCAT-T has been validated in the broadest population and is probably the most clinically useful tool currently available. The MMSE is an attractive alternative because of its widespread use and familiarity; however, it is imprecise with scores from 17 to 23, limiting its applicability.

At a minimum, familiarity with the core legal standards of capacity (communication of choice, understanding, appreciation, and reasoning) will improve a hospitalist’s ability to identify patients who lack capacity. Understanding and applying the defined markers most often provides a sufficient capacity evaluation in itself. As capacity is not static, the decision usually requires more than one assessment.

Equally, deciding that a patient lacks capacity is not an end in itself, and the underlying cause should be addressed. Certain factors, such as infection, medication, time of day, and relationship with the clinician doing the assessment, can affect a patient’s capacity. These should be addressed through treatment, education, and social support whenever possible in order to optimize a patient’s performance during the capacity evaluation. If the decision can be delayed until a time when the patient can regain capacity, this should be done in order to maximize the patient’s autonomy.11

Risk-related standards of capacity.

Although some question the notion, given our desire to facilitate management beneficial to the patient, the general consensus is that we have a lower threshold for capacity for consent to treatments that are low-risk and high-benefit.12,13 We would then have a somewhat higher threshold for capacity to refuse that same treatment. Stemming from a desire to protect patients from harm, we have a relatively higher threshold for capacity to make decisions regarding high-risk, low-benefit treatments. For the remainder of cases (low risk/low benefit; high risk/high benefit), as well as treatments that significantly impact a patient’s lifestyle (e.g. dialysis, amputation), we have a low capacity to let patients decide for themselves.11,14

Other considerations.

Clinicians should be thorough in documenting details in coming to a capacity determination, both as a means to formalize the thought process running through the four determinants of capacity, and in order to document for future reference. Cases in which it could be reasonable to call a consultant for those familiar with the assessment basics include:

- Cases in which a determination of lack of capacity could adversely affect the hospitalist’s relationship with the patient;

- Cases in which the hospitalist lacks the time to properly perform the evaluation;

- Particularly difficult or high-stakes cases (e.g. cases that might involve legal proceedings); and

- Cases in which significant mental illness affects a patient’s capacity.11

Early involvement of potential surrogate decision-makers is wise for patients in whom capacity is questioned, both for obtaining collateral history as well as initiating dialogue as to the patient’s wishes. When a patient is found to lack capacity, resources to utilize to help make a treatment decision include existing advance directives and substitute decision-makers, such as durable power of attorneys (DPOAs) and family members. In those rare cases in which clinicians are unable to reach a consensus about a patient’s capacity, an ethics consult should be considered.

Back to the Case.

Following the patient’s declaration that dialysis is not something he is interested in, his niece reports that he is a minimalist when it comes to interventions, and that he had similarly refused a cardiac catheterization in the 1990s. You review with the patient and niece that dialysis would be a procedure to replace his failing kidney function, and that failure to pursue this would ultimately be life-threatening and likely result in death, especially in regard to electrolyte abnormalities and his lack of any other terminal illness.

The consulting nephrologist reviews their recommendations with the patient and niece as well, and the patient consistently refuses. Having clearly communicated his choice, you ask the patient if he understands the situation. He says, "My kidneys are failing. That’s how I got the high potassium." You ask him what that means. "They aren’t going to function on their own much longer," he says. "I could die from it."

You confirm his ideas, and ask him why he doesn’t want dialysis. "I don’t want dialysis because I don’t want to spend my life hooked up to machines three times a week," the patient explains. "I just want to let things run their natural course." The niece says her uncle wouldn’t have wanted dialysis even if it were 10 years ago, so she’s not surprised he is refusing now.

Following this discussion, you feel comfortable that the patient has capacity to make this decision. Having documented this discussion, you discharge him to a subacute rehabilitation facility.

Bottom Line.

In cases in which capacity is in question, a hospitalist’s case-by-case review of the four components of capacity—communicating a choice, understanding, appreciation, and rationalization and reasoning—is warranted to help determine whether a patient has capacity. In cases in which a second opinion is warranted, psychiatry, geriatrics, or ethics consults could be utilized.

Drs. Dastidar and Odden are hospitalists at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor.

References

- Buchanan A, Brock DW. Deciding for others. Milbank Q. 1986;64(Suppl. 2):17-94.

- Guidelines for assessing the decision-making capacities of potential research subjects with cognitive impairment. American Psychiatric Association. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155(11):1649-50.

- Appelbaum PS, Grisso T. Assessing patients’ capacities to consent to treatment. N Engl J Med. 1988;319(25):1635-1638.

- Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189-198.

- Etchells E, Darzins P, Silberfeld M, et al. Assessment of patient capacity to consent to treatment. J Gen Intern Med. 1999;14:27-34.

- Grisso T, Appelbaum PS, Hill-Fotouhi C. The MacCAT-T: a clinical tool to assess patients’ capacities to make treatment decisions. Psychiatr Serv. 1997;48:1415- 1419.

- Marson DC, Ingram KK, Cody HA, Harrell LE. Assessing the competency of patients with Alzheimer’s disease under different legal standards. A prototype instrument. Arch Neurol. 1995;52:949-954.

- Edelstein B. Hopemont Capacity Assessment Interview Manual and Scoring Guide. 1999: Morgantown, W.V.: West Virginia University.

- Pruchno RA, Smyer MA, Rose MS, Hartman-Stein PE, Henderson-Laribee DL. Competence of long-term care residents to participate in decisions about their medical care: a brief, objective assessment. Gerontologist. 1995;35:622-629.

- Moye J, Karel M, Azar AR, Gurrera R. Capacity to consent to treatment: empirical comparison of three instruments in older adults with and without dementia. Gerontologist. 2004;44:166-175.

- Grisso T, Appelbaum PS. Assessing competence to consent to treatment: a guide for physicians and other health professionals. 1998; New York: Oxford University Press, 211.

- Cale GS. Risk-related standards of competence: continuing the debate over risk-related standards of competence. Bioethics. 1999;13(2):131-148.

- Checkland D. On risk and decisional capacity. J Med Philos. 2001;26(1):35-59.

- Wilks I. The debate over risk-related standards of competence. Bioethics. 1997;11(5):413-426.

- Ganzini L, Volicer L, Nelson WA, Fox E, Derse AR. Ten myths about decision-making capacity. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2004;5(4):263-267.

Acknowledgements:The authors would like to thank Dr. Jeff Rohde for reviewing a copy of the manuscript, and Dr. Amy Rosinski for providing direction from the psychiatry standpoint

Case

A 79-year-old male with coronary artery disease, hypertension, non-insulin-dependent mellitus, moderate dementia, and chronic renal insufficiency is admitted after a fall evaluation. He is widowed and lives in an assisted living facility. He’s accompanied by his niece, is alert, and oriented to person. He thinks he is in a clinic and is unable to state the year, but the remainder of the examination is unremarkable. His labs are notable for potassium of 6.3 mmol/L, BUN of 78 mg/dL, and Cr of 3.7 mg/dL. The niece reports that the patient is not fond of medical care, thus the most recent labs are from two years ago (and indicate a BUN of 39 and Cr of 2.8, with an upward trend over the past decade). You discuss possible long-term need for dialysis with the patient and niece, and the patient clearly states "no." However, he also states that it is 1988. How do you determine if he has the capacity to make decisions?

Overview

Hospitalists are familiar with the doctrine of informed consent—describing a disease, treatment options, associated risks and benefits, potential for complications, and alternatives, including no treatment. Not only must the patient be informed, and the decision free from any coercion, but the patient also must have capacity to make the decision.

Hospitalists often care for patients in whom decision-making capacity comes into question. This includes populations with depression, psychosis, dementia, stroke, severe personality disorders, developmental delay, comatose patients, as well as those with impaired attentional capacity (e.g. acute pain) or general debility (e.g. metastatic cancer).1,2

ave for the comatose patient, whether the patient has capacity might not be obvious. However, addressing the components of capacity (communication, understanding, appreciation, and rationalization) by using a validated clinical tool, such as the MacCAT-T, or more simply by systematically applying those four components to the clinical scenario under consideration, hospitalists can make this determination.

Review of the Literature

It is important to differentiate capacity from competency. Competency is a global assessment and a legal determination made by a judge in court. Capacity, on the other hand, is a functional assessment regarding a particular decision. Capacity is not static, and it can be performed by any clinician familiar with the patient. A hospitalist often is well positioned to make a capacity determination given established rapport with the patient and familiarity with the details of the case.

To make this determination, a hospitalist needs to know how to assess capacity. Although capacity usually is defined by state law and varies by jurisdiction, clinicians generally can assume it includes one or more of the four key components:

- Communication. The patient needs to be able to express a treatment choice, and this decision needs to be stable enough for the treatment to be implemented. Changing one’s decision in itself would not bring a patient’s capacity into question, so long as the patient was able to explain the rationale behind the switch. Frequent changes back and forth in the decision-making, however, could be indicative of an underlying psychiatric disorder or extreme indecision, which could bring capacity into question.

- Understanding. The patient needs to recall conversations about treatment, to make the link between causal relationships, and to process probabilities for outcomes. Problems with memory, attention span, and intelligence can affect one’s understanding.

- Appreciation. The patient should be able to identify the illness, treatment options, and likely outcomes as things that will affect him or her directly. A lack of appreciation usually stems from a denial based on intelligence (lack of a capability to understand) or emotion, or a delusion that the patient is not affected by this situation the same way and will have a different outcome.

- Rationalization or reasoning. The patient needs to be able to weigh the risks and benefits of the treatment options presented to come to a conclusion in keeping with their goals and best interests, as defined by their personal set of values. This often is affected in psychosis, depression, anxiety, phobias, delirium, and dementia.3

Several clinical capacity tools have been developed to assess these components:

Clinical tools.

The Mini-Mental Status Examination (MMSE) is a bedside test of a patient’s cognitive function, with scores ranging from 0 to 30.4 Although it wasn’t developed for assessing decision-making capacity, it has been compared with expert evaluation for assessment of capacity; the test performs reasonably well, particularly with high and low scores. Specifically, a MMSE >24 has a negative likelihood ratio (LR) of 0.05 for lack of capacity, while a MMSE <16 has a positive LR of 15.5 Scores from 17 to 23 do not correlate well with capacity, and further testing would be necessary. It is easy to administer, requires no formal training, and is familiar to most hospitalists. However, it does not address any specific aspects of informed consent, such as understanding or choice, and has not been validated in patients with mental illness.

The MacArthur Competence Assessment Tools for Treatment (MacCAT-T) is regarded as the gold standard for capacity assessment aids. It utilizes hospital chart review followed by a semi-structured interview to address clinical issues relevant to the patient being assessed; it takes 15 to 20 minutes to complete.6 The test provides scores in each of the four domains (choice, understanding, appreciation, and reasoning) of capacity. It has been validated in patients with dementia, schizophrenia, and depression. Limiting its clinical applicability is the fact that the MacCAT-T requires training to administer and interpret the results, though this is a relatively brief process.

The Capacity to Consent to Treatment Instrument (CCTI) uses hypothetical clinical vignettes in a structured interview to assess capacity across all four domains. The tool was developed and validated in patients with dementia and Parkinson’s disease, and takes 20 to 25 minutes to complete.7 A potential limitation is the CCTI’s use of vignettes as opposed to a patient-specific discussion, which could lead to different patient answers and a false assessment of the patient’s capacity.

The Hopemont Capacity Assessment Interview (HCAI) utilizes hypothetical vignettes in a semi-structured interview format to assess understanding, appreciation, choice, and likely reasoning.8,9 Similar to CCTI, HCAI is not modified for individual patients. Rather, it uses clinical vignettes to gauge a patient’s ability to make decisions. The test takes 30 to 60 minutes to administer and performs less well in assessing appreciation and reasoning than the MacCAT-T and CCTI.10

It is not necessary to perform a formal assessment of capacity on every inpatient. For most, there is no reasonable concern for impaired capacity, obviating the need for formal testing. Likewise, in patients who clearly lack capacity, such as those with end-stage dementia or established guardians, formal reassessment usually is not required. Formal testing is most useful in situations in which capacity is unclear, disagreement amongst surrogate decision-makers exists, or judicial involvement is anticipated.

The MacCAT-T has been validated in the broadest population and is probably the most clinically useful tool currently available. The MMSE is an attractive alternative because of its widespread use and familiarity; however, it is imprecise with scores from 17 to 23, limiting its applicability.

At a minimum, familiarity with the core legal standards of capacity (communication of choice, understanding, appreciation, and reasoning) will improve a hospitalist’s ability to identify patients who lack capacity. Understanding and applying the defined markers most often provides a sufficient capacity evaluation in itself. As capacity is not static, the decision usually requires more than one assessment.

Equally, deciding that a patient lacks capacity is not an end in itself, and the underlying cause should be addressed. Certain factors, such as infection, medication, time of day, and relationship with the clinician doing the assessment, can affect a patient’s capacity. These should be addressed through treatment, education, and social support whenever possible in order to optimize a patient’s performance during the capacity evaluation. If the decision can be delayed until a time when the patient can regain capacity, this should be done in order to maximize the patient’s autonomy.11

Risk-related standards of capacity.

Although some question the notion, given our desire to facilitate management beneficial to the patient, the general consensus is that we have a lower threshold for capacity for consent to treatments that are low-risk and high-benefit.12,13 We would then have a somewhat higher threshold for capacity to refuse that same treatment. Stemming from a desire to protect patients from harm, we have a relatively higher threshold for capacity to make decisions regarding high-risk, low-benefit treatments. For the remainder of cases (low risk/low benefit; high risk/high benefit), as well as treatments that significantly impact a patient’s lifestyle (e.g. dialysis, amputation), we have a low capacity to let patients decide for themselves.11,14

Other considerations.

Clinicians should be thorough in documenting details in coming to a capacity determination, both as a means to formalize the thought process running through the four determinants of capacity, and in order to document for future reference. Cases in which it could be reasonable to call a consultant for those familiar with the assessment basics include:

- Cases in which a determination of lack of capacity could adversely affect the hospitalist’s relationship with the patient;

- Cases in which the hospitalist lacks the time to properly perform the evaluation;

- Particularly difficult or high-stakes cases (e.g. cases that might involve legal proceedings); and

- Cases in which significant mental illness affects a patient’s capacity.11

Early involvement of potential surrogate decision-makers is wise for patients in whom capacity is questioned, both for obtaining collateral history as well as initiating dialogue as to the patient’s wishes. When a patient is found to lack capacity, resources to utilize to help make a treatment decision include existing advance directives and substitute decision-makers, such as durable power of attorneys (DPOAs) and family members. In those rare cases in which clinicians are unable to reach a consensus about a patient’s capacity, an ethics consult should be considered.

Back to the Case.

Following the patient’s declaration that dialysis is not something he is interested in, his niece reports that he is a minimalist when it comes to interventions, and that he had similarly refused a cardiac catheterization in the 1990s. You review with the patient and niece that dialysis would be a procedure to replace his failing kidney function, and that failure to pursue this would ultimately be life-threatening and likely result in death, especially in regard to electrolyte abnormalities and his lack of any other terminal illness.

The consulting nephrologist reviews their recommendations with the patient and niece as well, and the patient consistently refuses. Having clearly communicated his choice, you ask the patient if he understands the situation. He says, "My kidneys are failing. That’s how I got the high potassium." You ask him what that means. "They aren’t going to function on their own much longer," he says. "I could die from it."

You confirm his ideas, and ask him why he doesn’t want dialysis. "I don’t want dialysis because I don’t want to spend my life hooked up to machines three times a week," the patient explains. "I just want to let things run their natural course." The niece says her uncle wouldn’t have wanted dialysis even if it were 10 years ago, so she’s not surprised he is refusing now.

Following this discussion, you feel comfortable that the patient has capacity to make this decision. Having documented this discussion, you discharge him to a subacute rehabilitation facility.

Bottom Line.

In cases in which capacity is in question, a hospitalist’s case-by-case review of the four components of capacity—communicating a choice, understanding, appreciation, and rationalization and reasoning—is warranted to help determine whether a patient has capacity. In cases in which a second opinion is warranted, psychiatry, geriatrics, or ethics consults could be utilized.

Drs. Dastidar and Odden are hospitalists at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor.

References

- Buchanan A, Brock DW. Deciding for others. Milbank Q. 1986;64(Suppl. 2):17-94.

- Guidelines for assessing the decision-making capacities of potential research subjects with cognitive impairment. American Psychiatric Association. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155(11):1649-50.

- Appelbaum PS, Grisso T. Assessing patients’ capacities to consent to treatment. N Engl J Med. 1988;319(25):1635-1638.

- Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189-198.

- Etchells E, Darzins P, Silberfeld M, et al. Assessment of patient capacity to consent to treatment. J Gen Intern Med. 1999;14:27-34.

- Grisso T, Appelbaum PS, Hill-Fotouhi C. The MacCAT-T: a clinical tool to assess patients’ capacities to make treatment decisions. Psychiatr Serv. 1997;48:1415- 1419.

- Marson DC, Ingram KK, Cody HA, Harrell LE. Assessing the competency of patients with Alzheimer’s disease under different legal standards. A prototype instrument. Arch Neurol. 1995;52:949-954.

- Edelstein B. Hopemont Capacity Assessment Interview Manual and Scoring Guide. 1999: Morgantown, W.V.: West Virginia University.

- Pruchno RA, Smyer MA, Rose MS, Hartman-Stein PE, Henderson-Laribee DL. Competence of long-term care residents to participate in decisions about their medical care: a brief, objective assessment. Gerontologist. 1995;35:622-629.

- Moye J, Karel M, Azar AR, Gurrera R. Capacity to consent to treatment: empirical comparison of three instruments in older adults with and without dementia. Gerontologist. 2004;44:166-175.

- Grisso T, Appelbaum PS. Assessing competence to consent to treatment: a guide for physicians and other health professionals. 1998; New York: Oxford University Press, 211.

- Cale GS. Risk-related standards of competence: continuing the debate over risk-related standards of competence. Bioethics. 1999;13(2):131-148.

- Checkland D. On risk and decisional capacity. J Med Philos. 2001;26(1):35-59.

- Wilks I. The debate over risk-related standards of competence. Bioethics. 1997;11(5):413-426.

- Ganzini L, Volicer L, Nelson WA, Fox E, Derse AR. Ten myths about decision-making capacity. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2004;5(4):263-267.

Acknowledgements:The authors would like to thank Dr. Jeff Rohde for reviewing a copy of the manuscript, and Dr. Amy Rosinski for providing direction from the psychiatry standpoint