User login

Healthcare quality is defined as the degree to which health services for individuals and populations increase the likelihood of desired health outcomes and are consistent with current professional knowledge.1 Delivering high quality care to patients in the hospital setting is especially challenging, given the rapid pace of clinical care, the severity and multitude of patient conditions, and the interdependence of complex processes within the hospital system. Research has shown that hospitalized patients do not consistently receive recommended care2 and are at risk for experiencing preventable harm.3 In an effort to stimulate improvement, stakeholders have called for increased accountability, including enhanced transparency and differential payment based on performance. A growing number of hospital process and outcome measures are readily available to the public via the Internet.46 The Joint Commission, which accredits US hospitals, requires the collection of core quality measure data7 and sets the expectation that National Patient Safety Goals be met to maintain accreditation.8 Moreover, the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) has developed a Value‐Based Purchasing (VBP) plan intended to adjust hospital payment based on quality measures and the occurrence of certain hospital‐acquired conditions.9, 10

Because of their clinical expertise, understanding of hospital clinical operations, leadership of multidisciplinary inpatient teams, and vested interest to improve the systems in which they work, hospitalists are perfectly positioned to collaborate with their institutions to improve the quality of care delivered to inpatients. However, many hospitalists are inadequately prepared to engage in efforts to improve quality, because medical schools and residency programs have not traditionally included or emphasized healthcare quality and patient safety in their curricula.1113 In a survey of 389 internal medicine‐trained hospitalists, significant educational deficiencies were identified in the area of systems‐based practice.14 Specifically, the topics of quality improvement, team management, practice guideline development, health information systems management, and coordination of care between healthcare settings were listed as essential skills for hospitalist practice but underemphasized in residency training. Recognizing the gap between the needs of practicing physicians and current medical education provided in healthcare quality, professional societies have recently published position papers calling for increased training in quality, safety, and systems, both in medical school11 and residency training.15, 16

The Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) convened a Quality Summit in December 2008 to develop strategic plans related to healthcare quality. Summit attendees felt that most hospitalists lack the formal training necessary to evaluate, implement, and sustain system changes within the hospital. In response, the SHM Hospital Quality and Patient Safety (HQPS) Committee formed a Quality Improvement Education (QIE) subcommittee in 2009 to assess the needs of hospitalists with respect to hospital quality and patient safety, and to evaluate and expand upon existing educational programs in this area. Membership of the QIE subcommittee consisted of hospitalists with extensive experience in healthcare quality and medical education. The QIE subcommittee refined and expanded upon the healthcare quality and patient safety‐related competencies initially described in the Core Competencies in Hospital Medicine.17 The purpose of this report is to describe the development, provide definitions, and make recommendations on the use of the Hospital Quality and Patient Safety (HQPS) Competencies.

Development of The Hospital Quality and Patient Safety Competencies

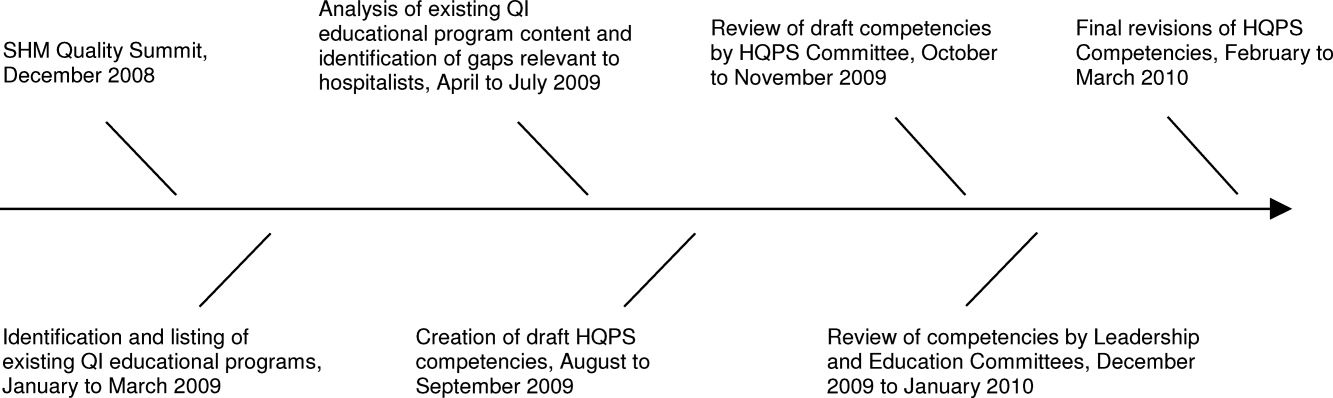

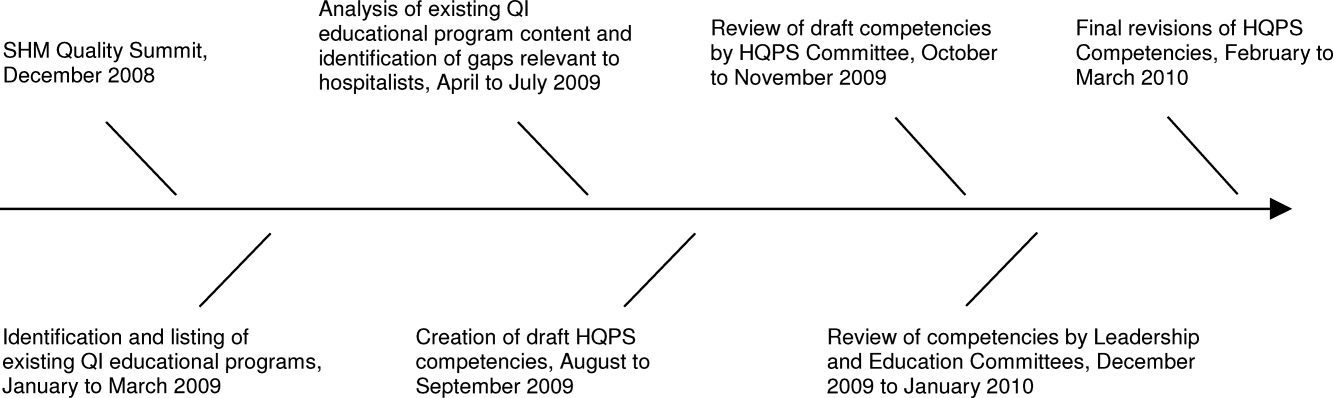

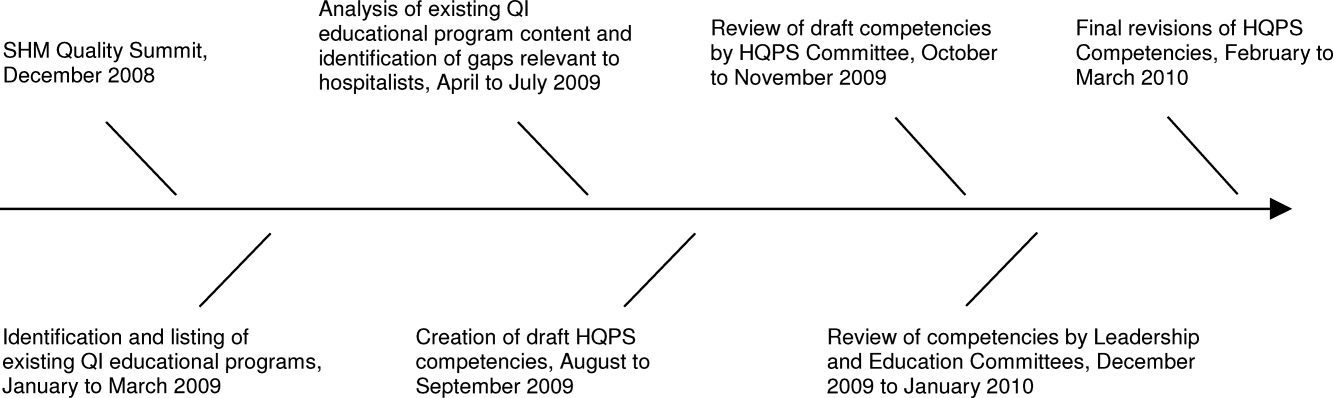

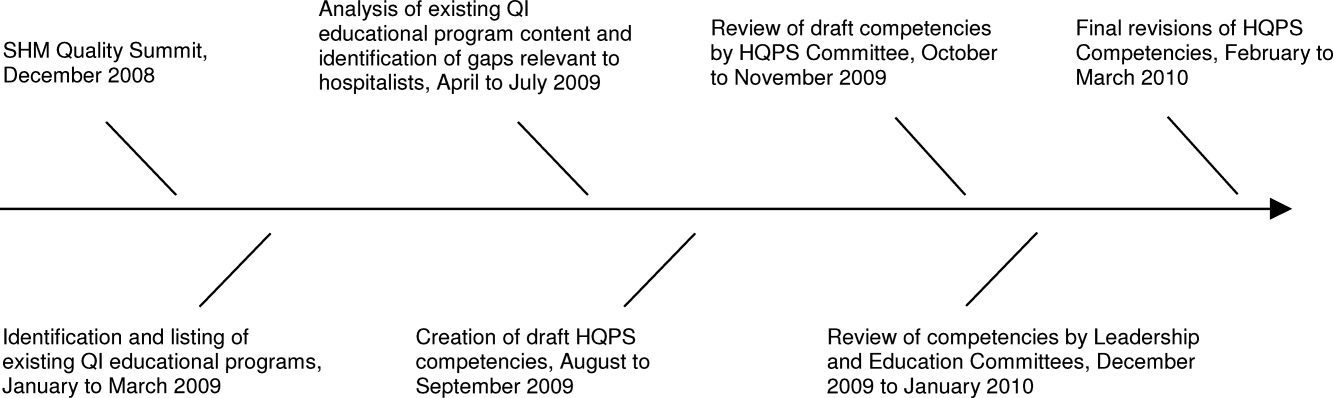

The multistep process used by the SHM QIE subcommittee to develop the HQPS Competencies is summarized in Figure 1. We performed an in‐depth evaluation of current educational materials and offerings, including a review of the Core Competencies in Hospital Medicine, past annual SHM Quality Improvement Pre‐Course objectives, and the content of training courses offered by other organizations.1722 Throughout our analysis, we emphasized the identification of gaps in content relevant to hospitalists. We then used the Institute of Medicine's (IOM) 6 aims for healthcare quality as a foundation for developing the HQPS Competencies.1 Specifically, the IOM states that healthcare should be safe, effective, patient‐centered, timely, efficient, and equitable. Additionally, we reviewed and integrated elements of the Practice‐Based Learning and Improvement (PBLI) and Systems‐Based Practice (SBP) competencies as defined by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME).23 We defined general areas of competence and specific standards for knowledge, skills, and attitudes within each area. Subcommittee members reflected on their own experience, as clinicians, educators, and leaders in healthcare quality and patient safety, to inform and refine the competency definitions and standards. Acknowledging that some hospitalists may serve as collaborators or clinical content experts, while others may serve as leaders of hospital quality initiatives, 3 levels of expertise were established: basic, intermediate, and advanced.

The QIE subcommittee presented a draft version of the HQPS Competencies to the HQPS Committee in the fall of 2009 and incorporated suggested revisions. The revised set of competencies was then reviewed by members of the Leadership and Education Committees during the winter of 2009‐2010, and additional recommendations were included in the final version now described.

Description of The Competencies

The 8 areas of competence include: Quality Measurement and Stakeholder Interests, Data Acquisition and Interpretation, Organizational Knowledge and Leadership Skills, Patient Safety Principles, Teamwork and Communication, Quality and Safety Improvement Methods, Health Information Systems, and Patient Centeredness. Three levels of competence and standards within each level and area are defined in Table 1. Standards use carefully selected action verbs to reflect educational goals for hospitalists at each level.24 The basic level represents a minimum level of competency for all practicing hospitalists. The intermediate level represents a hospitalist who is prepared to meaningfully engage and collaborate with his or her institution in quality improvement efforts. A hospitalist at this level may also lead uncomplicated improvement projects for his or her medical center and/or hospital medicine group. The advanced level represents a hospitalist prepared to lead quality improvement efforts for his or her institution and/or hospital medicine group. Many hospitalists at this level will have, or will be prepared to have, leadership positions in quality and patient safety at their institutions. Advanced level hospitalists will also have the expertise to teach and mentor other individuals in their quality improvement efforts.

| Competency | Basic | Intermediate | Advanced |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Quality measurement and stakeholder interests | Define structure, process, and outcome measures | Compare and contrast relative benefits of using one type of measure vs another | Anticipate and respond to stakeholders' needs and interests |

| Define stakeholders and understand their interests related to healthcare quality | Explain measures as defined by stakeholders (Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services, Leapfrog, etc) | Anticipate and respond to changes in quality measures and incentive programs | |

| Identify measures as defined by stakeholders (Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services, Leapfrog, etc) | Appreciate variation in quality and utilization performance | Lead efforts to reduce variation in care delivery (see also quality improvement methods) | |

| Describe potential unintended consequences of quality measurement and incentive programs | Avoid unintended consequences of quality measurement and incentive programs | ||

| Data acquisition and interpretation | Interpret simple statistical methods to compare populations within a sample (chi‐square, t tests, etc) | Describe sources of data for quality measurement | Acquire data from internal and external sources |

| Define basic terms used to describe continuous and categorical data (mean, median, standard deviation, interquartile range, percentages, rates, etc) | Identify potential pitfalls in administrative data | Create visual representations of data (Bar, Pareto, and Control Charts) | |

| Summarize basic principles of statistical process control | Explain variation in data | Use simple statistical methods to compare populations within a sample (chi‐square, t tests, etc) | |

| Interpret data displayed in Pareto and Control Charts | Administer and interpret a survey | ||

| Summarize basic survey techniques (including methods to maximize response, minimize bias, and use of ordinal response scales) | |||

| Use appropriate terms to describe continuous and categorical data (mean, median, standard deviation, interquartile range, percentages, rates, etc) | |||

| Organizational knowledge and leadership skills | Describe the organizational structure of one's institution | Define interests of internal and external stakeholders | Effectively negotiate with stakeholders |

| Define leaders within the organization and describe their roles | Collaborate as an effective team member of a quality improvement project | Assemble a quality improvement project team and effectively lead meetings (setting agendas, hold members accountable, etc) | |

| Exemplify the importance of leading by example | Explain principles of change management and how it can positively or negatively impact quality improvement project implementation | Motivate change and create vision for ideal state | |

| Effectively communicate quality or safety issues identified during routine patient care to the appropriate parties | Communicate effectively in a variety of settings (lead a meeting, public speaking, etc) | ||

| Serve as a resource and/or mentor for less‐experienced team members | |||

| Patient safety principles | Identify potential sources of error encountered during routine patient care | Compare methods to measure errors and adverse events, including administrative data analysis, chart review, and incident reporting systems | Lead efforts to appropriately measure medical error and/or adverse events |

| Compare and contrast medical error with adverse event | Identify and explain how human factors can contribute to medical errors | Lead efforts to redesign systems to reduce errors from occurring; this may include the facilitation of a hospital, departmental, or divisional Root Cause Analysis | |

| Describe how the systems approach to medical error is more productive than assigning individual blame | Know the difference between a strong vs a weak action plan for improvement (ie, brief education intervention is weak; skills training with deliberate practice or physical changes are stronger) | Lead efforts to advance the culture of patient safety in the hospital | |

| Differentiate among types of error (knowledge/judgment vs systems vs procedural/technical; latent vs active) | |||

| Explain the role that incident reporting plays in quality improvement efforts and how reporting can foster a culture of safety | |||

| Describe principles of medical error disclosure | |||

| Teamwork and communication | Explain how poor teamwork and communication failures contribute to adverse events | Collaborate on administration and interpretation of teamwork and safety culture measures | Lead efforts to improve teamwork and safety culture |

| Identify the potential for errors during transitions within and between healthcare settings (handoffs, transfers, discharge) | Describe the principles of effective teamwork and identify behaviors consistent with effective teamwork | Lead efforts to improve teamwork in specific settings (intensive care, medical‐surgical unit, etc) | |

| Identify deficiencies in transitions within and between healthcare settings (handoffs, transfers, discharge) | Successfully improve the safety of transitions within and between healthcare settings (handoffs, transfers, discharge) | ||

| Quality and safety improvement methods and tools | Define the quality improvement methods used and infrastructure in place at one's hospital | Compare and contrast various quality improvement methods, including six sigma, lean, and PDSA | Lead a quality improvement project using six sigma, lean, or PDSA methodology |

| Summarize the basic principles and use of Root Cause Analysis as a tool to evaluate medical error | Collaborate on a quality improvement project using six sigma, lean, or PDSA | Use high level process mapping, fishbone diagrams, etc, to identify areas for opportunity in evaluating a process | |

| Describe and collaborate on Failure Mode and Effects Analysis | Lead the development and implementation of clinical protocols to standardize care delivery when appropriate | ||

| Actively participate in a Root Cause Analysis | Conduct Failure Mode and Effects Analysis | ||

| Conduct Root Cause Analysis | |||

| Health information systems | Identify the potential for information systems to reduce as well as contribute to medical error | Define types of clinical decision support | Lead or co‐lead efforts to leverage information systems in quality measurement |

| Describe how information systems fit into provider workflow and care delivery | Collaborate on the design of health information systems | Lead or co‐lead efforts to leverage information systems to reduce error and/or improve delivery of effective care | |

| Anticipate and prevent unintended consequences of implementation or revision of information systems | |||

| Lead or co‐lead efforts to leverage clinical decision support to improve quality and safety | |||

| Patient centeredness | Explain the clinical benefits of a patient‐centered approach | Explain benefits and potential limitations of patient satisfaction surveys | Interpret data from patient satisfaction surveys and lead efforts to improve patient satisfaction |

| Identify system barriers to effective and safe care from the patient's perspective | Identify clinical areas with suboptimal efficiency and/or timeliness from the patient's perspective | Lead effort to reduce inefficiency and/or improve timeliness from the patient's perspective | |

| Describe the value of patient satisfaction surveys and patient and family partnership in care | Promote patient and caregiver education including use of effective education tools | Lead efforts to eliminate system barriers to effective and safe care from the patient's perspective | |

| Lead efforts to improve patent and caregiver education including development or implementation of effective education tools | |||

| Lead efforts to actively involve patients and families in the redesign of healthcare delivery systems and processes | |||

Recommended Use of The Competencies

The HQPS Competencies provide a framework for curricula and other professional development experiences in healthcare quality and patient safety. We recommend a step‐wise approach to curriculum development which includes conducting a targeted needs assessment, defining goals and specific learning objectives, and evaluation of the curriculum.25 The HQPS Competencies can be used at each step and provide educational targets for learners across a range of interest and experience.

Professional Development

Since residency programs historically have not trained their graduates to achieve a basic level of competence, practicing hospitalists will need to seek out professional development opportunities. Some educational opportunities which already exist include the Quality Track sessions during the SHM Annual Meeting, and the SHM Quality Improvement Pre‐Course. Hospitalist leaders are currently using the HQPS Competencies to review and revise annual meeting and pre‐course objectives and content in an effort to meet the expected level of competence for SHM members. Similarly, local SHM Chapter and regional hospital medicine leaders should look to the competencies to help select topics and objectives for future presentations. Additionally, the SHM Web site offers tools to develop skills, including a resource room and quality improvement primer.26 Mentored‐implementation programs, supported by SHM, can help hospitalists' acquire more advanced experiential training in quality improvement.

New educational opportunities are being developed, including a comprehensive set of Internet‐based modules designed to help practicing hospitalists achieve a basic level of competence. Hospitalists will be able to achieve continuing medical education (CME) credit upon completion of individual modules. Plans are underway to provide Certification in Hospital Quality and Patient Safety, reflecting an advanced level of competence, upon completion of the entire set, and demonstration of knowledge and skill application through an approved quality improvement project. The certification process will leverage the success of the SHM Leadership Academies and Mentored Implementation projects to help hospitalists apply their new skills in a real world setting.

HQPS Competencies and Focused Practice in Hospital Medicine

Recently, the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) has recognized the field of hospital medicine by developing a new program that provides hospitalists the opportunity to earn Maintenance of Certification (MOC) in Internal Medicine with a Focused Practice in Hospital Medicine.27 Appropriately, hospital quality and patient safety content is included among the knowledge questions on the secure exam, and completion of a practice improvement module (commonly known as PIM) is required for the certification. The SHM Education Committee has developed a Self‐Evaluation of Medical Knowledge module related to hospital quality and patient safety for use in the MOC process. ABIM recertification with Focused Practice in Hospital Medicine is an important and visible step for the Hospital Medicine movement; the content of both the secure exam and the MOC reaffirms the notion that the acquisition of knowledge, skills, and attitudes in hospital quality and patient safety is essential to the practice of hospital medicine.

Medical Education

Because teaching hospitalists frequently serve in important roles as educators and physician leaders in quality improvement, they are often responsible for medical student and resident training in healthcare quality and patient safety. Medical schools and residency programs have struggled to integrate healthcare quality and patient safety into their curricula.11, 12, 28 Hospitalists can play a major role in academic medical centers by helping to develop curricular materials and evaluations related to healthcare quality. Though intended primarily for future and current hospitalists, the HQPS Competencies and standards for the basic level may be adapted to provide educational targets for many learners in undergraduate and graduate medical education. Teaching hospitalists may use these standards to evaluate current educational efforts and design new curricula in collaboration with their medical school and residency program leaders.

Beyond the basic level of training in healthcare quality required for all, many residents will benefit from more advanced training experiences, including opportunities to apply knowledge and develop skills related to quality improvement. A recent report from the ACGME concluded that role models and mentors were essential for engaging residents in quality improvement efforts.29 Hospitalists are ideally suited to serve as role models during residents' experiential learning opportunities related to hospital quality. Several residency programs have begun to implement hospitalist tracks13 and quality improvement rotations.3032 Additionally, some academic medical centers have begun to develop and offer fellowship training in Hospital Medicine.33 These hospitalist‐led educational programs are an ideal opportunity to teach the intermediate and advanced training components, of healthcare quality and patient safety, to residents and fellows that wish to incorporate activity or leadership in quality improvement and patient safety science into their generalist or subspecialty careers. Teaching hospitalists should use the HQPS competency standards to define learning objectives for trainees at this stage of development.

To address the enormous educational needs in quality and safety for future physicians, a cadre of expert teachers in quality and safety will need to be developed. In collaboration with the Alliance for Academic Internal Medicine (AAIM), SHM is developing a Quality and Safety Educators Academy which will target academic hospitalists and other medical educators interested in developing advanced skills in quality improvement and patient safety education.

Assessment of Competence

An essential component of a rigorous faculty development program or medical education initiative is the assessment of whether these endeavors are achieving their stated aims. Published literature provides examples of useful assessment methods applicable to the HQPS Competencies. Knowledge in several areas of HQPS competence may be assessed with the use of multiple choice tests.34, 35 Knowledge of quality improvement methods may be assessed using the Quality Improvement Knowledge Application Tool (QIKAT), an instrument in which the learner responds to each of 3 scenarios with an aim, outcome and process measures, and ideas for changes which may result in improved performance.36 Teamwork and communication skills may be assessed using 360‐degree evaluations3739 and direct observation using behaviorally anchored rating scales.4043 Objective structured clinical examinations have been used to assess knowledge and skills related to patient safety principles.44, 45 Notably, few studies have rigorously assessed the validity and reliability of tools designed to evaluate competence related to healthcare quality.46 Additionally, to our knowledge, no prior research has evaluated assessment specifically for hospitalists. Thus, the development and validation of new assessment tools based on the HQPS Competencies for learners at each level is a crucial next step in the educational process. Additionally, evaluation of educational initiatives should include analyses of clinical benefit, as the ultimate goal of these efforts is to improve patient care.47, 48

Conclusion

Hospitalists are poised to have a tremendous impact on improving the quality of care for hospitalized patients. The lack of training in quality improvement in traditional medical education programs, in which most current hospitalists were trained, can be overcome through appropriate use of the HQPS Competencies. Formal incorporation of the HQPS Competencies into professional development programs, and innovative educational initiatives and curricula, will help provide current hospitalists and the next generations of hospitalists with the needed skills to be successful.

- Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the Twenty‐first Century.Washington, DC:Institute of Medicine;2001.

- ,,,.Care in U.S. hospitals—the Hospital Quality Alliance program.N Engl J Med.2005;353(3):265–274.

- ,.Excess length of stay, charges, and mortality attributable to medical injuries during hospitalization.JAMA.2003;290(14):1868–1874.

- Hospital Compare—A quality tool provided by Medicare. Available at: http://www.hospitalcompare.hhs.gov/. Accessed April 23,2010.

- The Leapfrog Group: Hospital Quality Ratings. Available at: http://www.leapfroggroup.org/cp. Accessed April 30,2010.

- Why Not the Best? A Healthcare Quality Improvement Resource. Available at: http://www.whynotthebest.org/. Accessed April 30,2010.

- The Joint Commission: Facts about ORYX for hospitals (National Hospital Quality Measures). Available at: http://www.jointcommission.org/accreditationprograms/hospitals/oryx/oryx_facts.htm. Accessed August 19,2010.

- The Joint Commission: National Patient Safety Goals. Available at: http://www.jointcommission.org/patientsafety/nationalpatientsafetygoals/. Accessed August 9,2010.

- Hospital Acquired Conditions: Overview. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/HospitalAcqCond/01_Overview.asp. Accessed April 30,2010.

- Report to Congress:Plan to Implement a Medicare Hospital Value‐based Purchasing Program. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services, Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services;2007.

- Unmet Needs: Teaching Physicians to Provide Safe Patient Care.Boston, MA:Lucian Leape Institute at the National Patient Safety Foundation;2010.

- ,,,,.Patient safety education at U.S. and Canadian medical schools: results from the 2006 Clerkship Directors in Internal Medicine survey.Acad Med.2009;84(12):1672–1676.

- ,,,,.Fulfilling the promise of hospital medicine: tailoring internal medicine training to address hospitalists' needs.J Gen Intern Med.2008;23(7):1110–1115.

- ,,,.Hospitalists' perceptions of their residency training needs: results of a national survey.Am J Med.2001;111(3):247–254.

- ,,,,.Redesigning residency education in internal medicine: a position paper from the Association of Program Directors in Internal Medicine.Ann Intern Med.2006;144(12):920–926.

- ,,.Redesigning training for internal medicine.Ann Intern Med.2006;144(12):927–932.

- ,,,,.Core competencies in hospital medicine: development and methodology.J Hosp Med.2006;1(1):48–56.

- Intermountain Healthcare. 20‐Day Course for Executives 2001.

- ,,,.Curriculum Development for Medical Education: A Six‐step Approach.Baltimore, MD:Johns Hopkins Press;1998.

- Society of Hospital Medicine Quality Improvement Basics. Available at: http://www.hospitalmedicine.org/Content/NavigationMenu/QualityImprovement/QIPrimer/QI_Primer_Landing_Pa.htm. Accessed June 4,2010.

- American Board of Internal Medicine: Questions and Answers Regarding ABIM's Maintenance of Certification in Internal Medicine With a Focused Practice in Hospital Medicine Program. Available at: http://www.abim.org/news/news/focused‐practice‐hospital‐medicine‐qa.aspx. Accessed August 9,2010.

- ,,.Assessing the needs of residency program directors to meet the ACGME general competencies.Acad Med.2002;77(7):750.

- .Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education and Institute for Healthcare Improvement 90‐Day Project. Involving Residents in Quality Improvement: Contrasting “Top‐Down” and “Bottom‐Up” Approaches.Chicago, IL;ACGME;2008.

- ,,,.Teaching internal medicine residents quality improvement techniques using the ABIM's practice improvement modules.J Gen Intern Med.2008;23(7):927–930.

- ,,,,.A self‐instructional model to teach systems‐based practice and practice‐based learning and improvement.J Gen Intern Med.2008;23(7):931–936.

- ,,,,.Creating a quality improvement elective for medical house officers.J Gen Intern Med.2004;19(8):861–867.

- ,,,.Hospital medicine fellowships: works in progress.Am J Med.2006;119(1):72.e1‐e7.

- ,,,.Web‐based education in systems‐based practice: a randomized trial.Arch Intern Med.2007;167(4):361–366.

- ,,,,.A self‐instructional model to teach systems‐based practice and practice‐based learning and improvement.J Gen Intern Med.2008;23(7):931–936.

- ,,,.The quality improvement knowledge application tool: an instrument to assess knowledge application in practice‐based learning and improvement.J Gen Intern Med.2003;18(suppl 1):250.

- ,,, et al.Effect of multisource feedback on resident communication skills and professionalism: a randomized controlled trial.Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med.2007;161(1):44–49.

- ,.Reliability of a 360‐degree evaluation to assess resident competence.Am J Phys Med Rehabil.2007;86(10):845–852.

- ,,,.Pilot study of a 360‐degree assessment instrument for physical medicine 82(5):394–402.

- ,,,,,.Anaesthetists' non‐technical skills (ANTS): evaluation of a behavioural marker system.Br J Anaesth.2003;90(5):580–588.

- ,,, et al.The Mayo high performance teamwork scale: reliability and validity for evaluating key crew resource management skills.Simul Healthc.2007;2(1):4–10.

- ,,,,,.Reliability of a revised NOTECHS scale for use in surgical teams.Am J Surg.2008;196(2):184–190.

- ,,,,,.Observational teamwork assessment for surgery: construct validation with expert versus novice raters.Ann Surg.2009;249(6):1047–1051.

- ,,,,,.A patient safety objective structured clinical examination.J Patient Saf.2009;5(2):55–60.

- ,.The Objective Structured Clinical Examination as an educational tool in patient safety.Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf.2007;33(1):48–53.

- ,,.Measurement of the general competencies of the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education: a systematic review.Acad Med.2009;84(3):301–309.

- ,,,,,.Effectiveness of teaching quality improvement to clinicians: a systematic review.JAMA.2007;298(9):1023–1037.

- ,,,,.Methodological rigor of quality improvement curricula for physician trainees: a systematic review and recommendations for change.Acad Med.2009;84(12):1677–1692.

Healthcare quality is defined as the degree to which health services for individuals and populations increase the likelihood of desired health outcomes and are consistent with current professional knowledge.1 Delivering high quality care to patients in the hospital setting is especially challenging, given the rapid pace of clinical care, the severity and multitude of patient conditions, and the interdependence of complex processes within the hospital system. Research has shown that hospitalized patients do not consistently receive recommended care2 and are at risk for experiencing preventable harm.3 In an effort to stimulate improvement, stakeholders have called for increased accountability, including enhanced transparency and differential payment based on performance. A growing number of hospital process and outcome measures are readily available to the public via the Internet.46 The Joint Commission, which accredits US hospitals, requires the collection of core quality measure data7 and sets the expectation that National Patient Safety Goals be met to maintain accreditation.8 Moreover, the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) has developed a Value‐Based Purchasing (VBP) plan intended to adjust hospital payment based on quality measures and the occurrence of certain hospital‐acquired conditions.9, 10

Because of their clinical expertise, understanding of hospital clinical operations, leadership of multidisciplinary inpatient teams, and vested interest to improve the systems in which they work, hospitalists are perfectly positioned to collaborate with their institutions to improve the quality of care delivered to inpatients. However, many hospitalists are inadequately prepared to engage in efforts to improve quality, because medical schools and residency programs have not traditionally included or emphasized healthcare quality and patient safety in their curricula.1113 In a survey of 389 internal medicine‐trained hospitalists, significant educational deficiencies were identified in the area of systems‐based practice.14 Specifically, the topics of quality improvement, team management, practice guideline development, health information systems management, and coordination of care between healthcare settings were listed as essential skills for hospitalist practice but underemphasized in residency training. Recognizing the gap between the needs of practicing physicians and current medical education provided in healthcare quality, professional societies have recently published position papers calling for increased training in quality, safety, and systems, both in medical school11 and residency training.15, 16

The Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) convened a Quality Summit in December 2008 to develop strategic plans related to healthcare quality. Summit attendees felt that most hospitalists lack the formal training necessary to evaluate, implement, and sustain system changes within the hospital. In response, the SHM Hospital Quality and Patient Safety (HQPS) Committee formed a Quality Improvement Education (QIE) subcommittee in 2009 to assess the needs of hospitalists with respect to hospital quality and patient safety, and to evaluate and expand upon existing educational programs in this area. Membership of the QIE subcommittee consisted of hospitalists with extensive experience in healthcare quality and medical education. The QIE subcommittee refined and expanded upon the healthcare quality and patient safety‐related competencies initially described in the Core Competencies in Hospital Medicine.17 The purpose of this report is to describe the development, provide definitions, and make recommendations on the use of the Hospital Quality and Patient Safety (HQPS) Competencies.

Development of The Hospital Quality and Patient Safety Competencies

The multistep process used by the SHM QIE subcommittee to develop the HQPS Competencies is summarized in Figure 1. We performed an in‐depth evaluation of current educational materials and offerings, including a review of the Core Competencies in Hospital Medicine, past annual SHM Quality Improvement Pre‐Course objectives, and the content of training courses offered by other organizations.1722 Throughout our analysis, we emphasized the identification of gaps in content relevant to hospitalists. We then used the Institute of Medicine's (IOM) 6 aims for healthcare quality as a foundation for developing the HQPS Competencies.1 Specifically, the IOM states that healthcare should be safe, effective, patient‐centered, timely, efficient, and equitable. Additionally, we reviewed and integrated elements of the Practice‐Based Learning and Improvement (PBLI) and Systems‐Based Practice (SBP) competencies as defined by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME).23 We defined general areas of competence and specific standards for knowledge, skills, and attitudes within each area. Subcommittee members reflected on their own experience, as clinicians, educators, and leaders in healthcare quality and patient safety, to inform and refine the competency definitions and standards. Acknowledging that some hospitalists may serve as collaborators or clinical content experts, while others may serve as leaders of hospital quality initiatives, 3 levels of expertise were established: basic, intermediate, and advanced.

The QIE subcommittee presented a draft version of the HQPS Competencies to the HQPS Committee in the fall of 2009 and incorporated suggested revisions. The revised set of competencies was then reviewed by members of the Leadership and Education Committees during the winter of 2009‐2010, and additional recommendations were included in the final version now described.

Description of The Competencies

The 8 areas of competence include: Quality Measurement and Stakeholder Interests, Data Acquisition and Interpretation, Organizational Knowledge and Leadership Skills, Patient Safety Principles, Teamwork and Communication, Quality and Safety Improvement Methods, Health Information Systems, and Patient Centeredness. Three levels of competence and standards within each level and area are defined in Table 1. Standards use carefully selected action verbs to reflect educational goals for hospitalists at each level.24 The basic level represents a minimum level of competency for all practicing hospitalists. The intermediate level represents a hospitalist who is prepared to meaningfully engage and collaborate with his or her institution in quality improvement efforts. A hospitalist at this level may also lead uncomplicated improvement projects for his or her medical center and/or hospital medicine group. The advanced level represents a hospitalist prepared to lead quality improvement efforts for his or her institution and/or hospital medicine group. Many hospitalists at this level will have, or will be prepared to have, leadership positions in quality and patient safety at their institutions. Advanced level hospitalists will also have the expertise to teach and mentor other individuals in their quality improvement efforts.

| Competency | Basic | Intermediate | Advanced |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Quality measurement and stakeholder interests | Define structure, process, and outcome measures | Compare and contrast relative benefits of using one type of measure vs another | Anticipate and respond to stakeholders' needs and interests |

| Define stakeholders and understand their interests related to healthcare quality | Explain measures as defined by stakeholders (Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services, Leapfrog, etc) | Anticipate and respond to changes in quality measures and incentive programs | |

| Identify measures as defined by stakeholders (Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services, Leapfrog, etc) | Appreciate variation in quality and utilization performance | Lead efforts to reduce variation in care delivery (see also quality improvement methods) | |

| Describe potential unintended consequences of quality measurement and incentive programs | Avoid unintended consequences of quality measurement and incentive programs | ||

| Data acquisition and interpretation | Interpret simple statistical methods to compare populations within a sample (chi‐square, t tests, etc) | Describe sources of data for quality measurement | Acquire data from internal and external sources |

| Define basic terms used to describe continuous and categorical data (mean, median, standard deviation, interquartile range, percentages, rates, etc) | Identify potential pitfalls in administrative data | Create visual representations of data (Bar, Pareto, and Control Charts) | |

| Summarize basic principles of statistical process control | Explain variation in data | Use simple statistical methods to compare populations within a sample (chi‐square, t tests, etc) | |

| Interpret data displayed in Pareto and Control Charts | Administer and interpret a survey | ||

| Summarize basic survey techniques (including methods to maximize response, minimize bias, and use of ordinal response scales) | |||

| Use appropriate terms to describe continuous and categorical data (mean, median, standard deviation, interquartile range, percentages, rates, etc) | |||

| Organizational knowledge and leadership skills | Describe the organizational structure of one's institution | Define interests of internal and external stakeholders | Effectively negotiate with stakeholders |

| Define leaders within the organization and describe their roles | Collaborate as an effective team member of a quality improvement project | Assemble a quality improvement project team and effectively lead meetings (setting agendas, hold members accountable, etc) | |

| Exemplify the importance of leading by example | Explain principles of change management and how it can positively or negatively impact quality improvement project implementation | Motivate change and create vision for ideal state | |

| Effectively communicate quality or safety issues identified during routine patient care to the appropriate parties | Communicate effectively in a variety of settings (lead a meeting, public speaking, etc) | ||

| Serve as a resource and/or mentor for less‐experienced team members | |||

| Patient safety principles | Identify potential sources of error encountered during routine patient care | Compare methods to measure errors and adverse events, including administrative data analysis, chart review, and incident reporting systems | Lead efforts to appropriately measure medical error and/or adverse events |

| Compare and contrast medical error with adverse event | Identify and explain how human factors can contribute to medical errors | Lead efforts to redesign systems to reduce errors from occurring; this may include the facilitation of a hospital, departmental, or divisional Root Cause Analysis | |

| Describe how the systems approach to medical error is more productive than assigning individual blame | Know the difference between a strong vs a weak action plan for improvement (ie, brief education intervention is weak; skills training with deliberate practice or physical changes are stronger) | Lead efforts to advance the culture of patient safety in the hospital | |

| Differentiate among types of error (knowledge/judgment vs systems vs procedural/technical; latent vs active) | |||

| Explain the role that incident reporting plays in quality improvement efforts and how reporting can foster a culture of safety | |||

| Describe principles of medical error disclosure | |||

| Teamwork and communication | Explain how poor teamwork and communication failures contribute to adverse events | Collaborate on administration and interpretation of teamwork and safety culture measures | Lead efforts to improve teamwork and safety culture |

| Identify the potential for errors during transitions within and between healthcare settings (handoffs, transfers, discharge) | Describe the principles of effective teamwork and identify behaviors consistent with effective teamwork | Lead efforts to improve teamwork in specific settings (intensive care, medical‐surgical unit, etc) | |

| Identify deficiencies in transitions within and between healthcare settings (handoffs, transfers, discharge) | Successfully improve the safety of transitions within and between healthcare settings (handoffs, transfers, discharge) | ||

| Quality and safety improvement methods and tools | Define the quality improvement methods used and infrastructure in place at one's hospital | Compare and contrast various quality improvement methods, including six sigma, lean, and PDSA | Lead a quality improvement project using six sigma, lean, or PDSA methodology |

| Summarize the basic principles and use of Root Cause Analysis as a tool to evaluate medical error | Collaborate on a quality improvement project using six sigma, lean, or PDSA | Use high level process mapping, fishbone diagrams, etc, to identify areas for opportunity in evaluating a process | |

| Describe and collaborate on Failure Mode and Effects Analysis | Lead the development and implementation of clinical protocols to standardize care delivery when appropriate | ||

| Actively participate in a Root Cause Analysis | Conduct Failure Mode and Effects Analysis | ||

| Conduct Root Cause Analysis | |||

| Health information systems | Identify the potential for information systems to reduce as well as contribute to medical error | Define types of clinical decision support | Lead or co‐lead efforts to leverage information systems in quality measurement |

| Describe how information systems fit into provider workflow and care delivery | Collaborate on the design of health information systems | Lead or co‐lead efforts to leverage information systems to reduce error and/or improve delivery of effective care | |

| Anticipate and prevent unintended consequences of implementation or revision of information systems | |||

| Lead or co‐lead efforts to leverage clinical decision support to improve quality and safety | |||

| Patient centeredness | Explain the clinical benefits of a patient‐centered approach | Explain benefits and potential limitations of patient satisfaction surveys | Interpret data from patient satisfaction surveys and lead efforts to improve patient satisfaction |

| Identify system barriers to effective and safe care from the patient's perspective | Identify clinical areas with suboptimal efficiency and/or timeliness from the patient's perspective | Lead effort to reduce inefficiency and/or improve timeliness from the patient's perspective | |

| Describe the value of patient satisfaction surveys and patient and family partnership in care | Promote patient and caregiver education including use of effective education tools | Lead efforts to eliminate system barriers to effective and safe care from the patient's perspective | |

| Lead efforts to improve patent and caregiver education including development or implementation of effective education tools | |||

| Lead efforts to actively involve patients and families in the redesign of healthcare delivery systems and processes | |||

Recommended Use of The Competencies

The HQPS Competencies provide a framework for curricula and other professional development experiences in healthcare quality and patient safety. We recommend a step‐wise approach to curriculum development which includes conducting a targeted needs assessment, defining goals and specific learning objectives, and evaluation of the curriculum.25 The HQPS Competencies can be used at each step and provide educational targets for learners across a range of interest and experience.

Professional Development

Since residency programs historically have not trained their graduates to achieve a basic level of competence, practicing hospitalists will need to seek out professional development opportunities. Some educational opportunities which already exist include the Quality Track sessions during the SHM Annual Meeting, and the SHM Quality Improvement Pre‐Course. Hospitalist leaders are currently using the HQPS Competencies to review and revise annual meeting and pre‐course objectives and content in an effort to meet the expected level of competence for SHM members. Similarly, local SHM Chapter and regional hospital medicine leaders should look to the competencies to help select topics and objectives for future presentations. Additionally, the SHM Web site offers tools to develop skills, including a resource room and quality improvement primer.26 Mentored‐implementation programs, supported by SHM, can help hospitalists' acquire more advanced experiential training in quality improvement.

New educational opportunities are being developed, including a comprehensive set of Internet‐based modules designed to help practicing hospitalists achieve a basic level of competence. Hospitalists will be able to achieve continuing medical education (CME) credit upon completion of individual modules. Plans are underway to provide Certification in Hospital Quality and Patient Safety, reflecting an advanced level of competence, upon completion of the entire set, and demonstration of knowledge and skill application through an approved quality improvement project. The certification process will leverage the success of the SHM Leadership Academies and Mentored Implementation projects to help hospitalists apply their new skills in a real world setting.

HQPS Competencies and Focused Practice in Hospital Medicine

Recently, the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) has recognized the field of hospital medicine by developing a new program that provides hospitalists the opportunity to earn Maintenance of Certification (MOC) in Internal Medicine with a Focused Practice in Hospital Medicine.27 Appropriately, hospital quality and patient safety content is included among the knowledge questions on the secure exam, and completion of a practice improvement module (commonly known as PIM) is required for the certification. The SHM Education Committee has developed a Self‐Evaluation of Medical Knowledge module related to hospital quality and patient safety for use in the MOC process. ABIM recertification with Focused Practice in Hospital Medicine is an important and visible step for the Hospital Medicine movement; the content of both the secure exam and the MOC reaffirms the notion that the acquisition of knowledge, skills, and attitudes in hospital quality and patient safety is essential to the practice of hospital medicine.

Medical Education

Because teaching hospitalists frequently serve in important roles as educators and physician leaders in quality improvement, they are often responsible for medical student and resident training in healthcare quality and patient safety. Medical schools and residency programs have struggled to integrate healthcare quality and patient safety into their curricula.11, 12, 28 Hospitalists can play a major role in academic medical centers by helping to develop curricular materials and evaluations related to healthcare quality. Though intended primarily for future and current hospitalists, the HQPS Competencies and standards for the basic level may be adapted to provide educational targets for many learners in undergraduate and graduate medical education. Teaching hospitalists may use these standards to evaluate current educational efforts and design new curricula in collaboration with their medical school and residency program leaders.

Beyond the basic level of training in healthcare quality required for all, many residents will benefit from more advanced training experiences, including opportunities to apply knowledge and develop skills related to quality improvement. A recent report from the ACGME concluded that role models and mentors were essential for engaging residents in quality improvement efforts.29 Hospitalists are ideally suited to serve as role models during residents' experiential learning opportunities related to hospital quality. Several residency programs have begun to implement hospitalist tracks13 and quality improvement rotations.3032 Additionally, some academic medical centers have begun to develop and offer fellowship training in Hospital Medicine.33 These hospitalist‐led educational programs are an ideal opportunity to teach the intermediate and advanced training components, of healthcare quality and patient safety, to residents and fellows that wish to incorporate activity or leadership in quality improvement and patient safety science into their generalist or subspecialty careers. Teaching hospitalists should use the HQPS competency standards to define learning objectives for trainees at this stage of development.

To address the enormous educational needs in quality and safety for future physicians, a cadre of expert teachers in quality and safety will need to be developed. In collaboration with the Alliance for Academic Internal Medicine (AAIM), SHM is developing a Quality and Safety Educators Academy which will target academic hospitalists and other medical educators interested in developing advanced skills in quality improvement and patient safety education.

Assessment of Competence

An essential component of a rigorous faculty development program or medical education initiative is the assessment of whether these endeavors are achieving their stated aims. Published literature provides examples of useful assessment methods applicable to the HQPS Competencies. Knowledge in several areas of HQPS competence may be assessed with the use of multiple choice tests.34, 35 Knowledge of quality improvement methods may be assessed using the Quality Improvement Knowledge Application Tool (QIKAT), an instrument in which the learner responds to each of 3 scenarios with an aim, outcome and process measures, and ideas for changes which may result in improved performance.36 Teamwork and communication skills may be assessed using 360‐degree evaluations3739 and direct observation using behaviorally anchored rating scales.4043 Objective structured clinical examinations have been used to assess knowledge and skills related to patient safety principles.44, 45 Notably, few studies have rigorously assessed the validity and reliability of tools designed to evaluate competence related to healthcare quality.46 Additionally, to our knowledge, no prior research has evaluated assessment specifically for hospitalists. Thus, the development and validation of new assessment tools based on the HQPS Competencies for learners at each level is a crucial next step in the educational process. Additionally, evaluation of educational initiatives should include analyses of clinical benefit, as the ultimate goal of these efforts is to improve patient care.47, 48

Conclusion

Hospitalists are poised to have a tremendous impact on improving the quality of care for hospitalized patients. The lack of training in quality improvement in traditional medical education programs, in which most current hospitalists were trained, can be overcome through appropriate use of the HQPS Competencies. Formal incorporation of the HQPS Competencies into professional development programs, and innovative educational initiatives and curricula, will help provide current hospitalists and the next generations of hospitalists with the needed skills to be successful.

Healthcare quality is defined as the degree to which health services for individuals and populations increase the likelihood of desired health outcomes and are consistent with current professional knowledge.1 Delivering high quality care to patients in the hospital setting is especially challenging, given the rapid pace of clinical care, the severity and multitude of patient conditions, and the interdependence of complex processes within the hospital system. Research has shown that hospitalized patients do not consistently receive recommended care2 and are at risk for experiencing preventable harm.3 In an effort to stimulate improvement, stakeholders have called for increased accountability, including enhanced transparency and differential payment based on performance. A growing number of hospital process and outcome measures are readily available to the public via the Internet.46 The Joint Commission, which accredits US hospitals, requires the collection of core quality measure data7 and sets the expectation that National Patient Safety Goals be met to maintain accreditation.8 Moreover, the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) has developed a Value‐Based Purchasing (VBP) plan intended to adjust hospital payment based on quality measures and the occurrence of certain hospital‐acquired conditions.9, 10

Because of their clinical expertise, understanding of hospital clinical operations, leadership of multidisciplinary inpatient teams, and vested interest to improve the systems in which they work, hospitalists are perfectly positioned to collaborate with their institutions to improve the quality of care delivered to inpatients. However, many hospitalists are inadequately prepared to engage in efforts to improve quality, because medical schools and residency programs have not traditionally included or emphasized healthcare quality and patient safety in their curricula.1113 In a survey of 389 internal medicine‐trained hospitalists, significant educational deficiencies were identified in the area of systems‐based practice.14 Specifically, the topics of quality improvement, team management, practice guideline development, health information systems management, and coordination of care between healthcare settings were listed as essential skills for hospitalist practice but underemphasized in residency training. Recognizing the gap between the needs of practicing physicians and current medical education provided in healthcare quality, professional societies have recently published position papers calling for increased training in quality, safety, and systems, both in medical school11 and residency training.15, 16

The Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) convened a Quality Summit in December 2008 to develop strategic plans related to healthcare quality. Summit attendees felt that most hospitalists lack the formal training necessary to evaluate, implement, and sustain system changes within the hospital. In response, the SHM Hospital Quality and Patient Safety (HQPS) Committee formed a Quality Improvement Education (QIE) subcommittee in 2009 to assess the needs of hospitalists with respect to hospital quality and patient safety, and to evaluate and expand upon existing educational programs in this area. Membership of the QIE subcommittee consisted of hospitalists with extensive experience in healthcare quality and medical education. The QIE subcommittee refined and expanded upon the healthcare quality and patient safety‐related competencies initially described in the Core Competencies in Hospital Medicine.17 The purpose of this report is to describe the development, provide definitions, and make recommendations on the use of the Hospital Quality and Patient Safety (HQPS) Competencies.

Development of The Hospital Quality and Patient Safety Competencies

The multistep process used by the SHM QIE subcommittee to develop the HQPS Competencies is summarized in Figure 1. We performed an in‐depth evaluation of current educational materials and offerings, including a review of the Core Competencies in Hospital Medicine, past annual SHM Quality Improvement Pre‐Course objectives, and the content of training courses offered by other organizations.1722 Throughout our analysis, we emphasized the identification of gaps in content relevant to hospitalists. We then used the Institute of Medicine's (IOM) 6 aims for healthcare quality as a foundation for developing the HQPS Competencies.1 Specifically, the IOM states that healthcare should be safe, effective, patient‐centered, timely, efficient, and equitable. Additionally, we reviewed and integrated elements of the Practice‐Based Learning and Improvement (PBLI) and Systems‐Based Practice (SBP) competencies as defined by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME).23 We defined general areas of competence and specific standards for knowledge, skills, and attitudes within each area. Subcommittee members reflected on their own experience, as clinicians, educators, and leaders in healthcare quality and patient safety, to inform and refine the competency definitions and standards. Acknowledging that some hospitalists may serve as collaborators or clinical content experts, while others may serve as leaders of hospital quality initiatives, 3 levels of expertise were established: basic, intermediate, and advanced.

The QIE subcommittee presented a draft version of the HQPS Competencies to the HQPS Committee in the fall of 2009 and incorporated suggested revisions. The revised set of competencies was then reviewed by members of the Leadership and Education Committees during the winter of 2009‐2010, and additional recommendations were included in the final version now described.

Description of The Competencies

The 8 areas of competence include: Quality Measurement and Stakeholder Interests, Data Acquisition and Interpretation, Organizational Knowledge and Leadership Skills, Patient Safety Principles, Teamwork and Communication, Quality and Safety Improvement Methods, Health Information Systems, and Patient Centeredness. Three levels of competence and standards within each level and area are defined in Table 1. Standards use carefully selected action verbs to reflect educational goals for hospitalists at each level.24 The basic level represents a minimum level of competency for all practicing hospitalists. The intermediate level represents a hospitalist who is prepared to meaningfully engage and collaborate with his or her institution in quality improvement efforts. A hospitalist at this level may also lead uncomplicated improvement projects for his or her medical center and/or hospital medicine group. The advanced level represents a hospitalist prepared to lead quality improvement efforts for his or her institution and/or hospital medicine group. Many hospitalists at this level will have, or will be prepared to have, leadership positions in quality and patient safety at their institutions. Advanced level hospitalists will also have the expertise to teach and mentor other individuals in their quality improvement efforts.

| Competency | Basic | Intermediate | Advanced |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Quality measurement and stakeholder interests | Define structure, process, and outcome measures | Compare and contrast relative benefits of using one type of measure vs another | Anticipate and respond to stakeholders' needs and interests |

| Define stakeholders and understand their interests related to healthcare quality | Explain measures as defined by stakeholders (Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services, Leapfrog, etc) | Anticipate and respond to changes in quality measures and incentive programs | |

| Identify measures as defined by stakeholders (Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services, Leapfrog, etc) | Appreciate variation in quality and utilization performance | Lead efforts to reduce variation in care delivery (see also quality improvement methods) | |

| Describe potential unintended consequences of quality measurement and incentive programs | Avoid unintended consequences of quality measurement and incentive programs | ||

| Data acquisition and interpretation | Interpret simple statistical methods to compare populations within a sample (chi‐square, t tests, etc) | Describe sources of data for quality measurement | Acquire data from internal and external sources |

| Define basic terms used to describe continuous and categorical data (mean, median, standard deviation, interquartile range, percentages, rates, etc) | Identify potential pitfalls in administrative data | Create visual representations of data (Bar, Pareto, and Control Charts) | |

| Summarize basic principles of statistical process control | Explain variation in data | Use simple statistical methods to compare populations within a sample (chi‐square, t tests, etc) | |

| Interpret data displayed in Pareto and Control Charts | Administer and interpret a survey | ||

| Summarize basic survey techniques (including methods to maximize response, minimize bias, and use of ordinal response scales) | |||

| Use appropriate terms to describe continuous and categorical data (mean, median, standard deviation, interquartile range, percentages, rates, etc) | |||

| Organizational knowledge and leadership skills | Describe the organizational structure of one's institution | Define interests of internal and external stakeholders | Effectively negotiate with stakeholders |

| Define leaders within the organization and describe their roles | Collaborate as an effective team member of a quality improvement project | Assemble a quality improvement project team and effectively lead meetings (setting agendas, hold members accountable, etc) | |

| Exemplify the importance of leading by example | Explain principles of change management and how it can positively or negatively impact quality improvement project implementation | Motivate change and create vision for ideal state | |

| Effectively communicate quality or safety issues identified during routine patient care to the appropriate parties | Communicate effectively in a variety of settings (lead a meeting, public speaking, etc) | ||

| Serve as a resource and/or mentor for less‐experienced team members | |||

| Patient safety principles | Identify potential sources of error encountered during routine patient care | Compare methods to measure errors and adverse events, including administrative data analysis, chart review, and incident reporting systems | Lead efforts to appropriately measure medical error and/or adverse events |

| Compare and contrast medical error with adverse event | Identify and explain how human factors can contribute to medical errors | Lead efforts to redesign systems to reduce errors from occurring; this may include the facilitation of a hospital, departmental, or divisional Root Cause Analysis | |

| Describe how the systems approach to medical error is more productive than assigning individual blame | Know the difference between a strong vs a weak action plan for improvement (ie, brief education intervention is weak; skills training with deliberate practice or physical changes are stronger) | Lead efforts to advance the culture of patient safety in the hospital | |

| Differentiate among types of error (knowledge/judgment vs systems vs procedural/technical; latent vs active) | |||

| Explain the role that incident reporting plays in quality improvement efforts and how reporting can foster a culture of safety | |||

| Describe principles of medical error disclosure | |||

| Teamwork and communication | Explain how poor teamwork and communication failures contribute to adverse events | Collaborate on administration and interpretation of teamwork and safety culture measures | Lead efforts to improve teamwork and safety culture |

| Identify the potential for errors during transitions within and between healthcare settings (handoffs, transfers, discharge) | Describe the principles of effective teamwork and identify behaviors consistent with effective teamwork | Lead efforts to improve teamwork in specific settings (intensive care, medical‐surgical unit, etc) | |

| Identify deficiencies in transitions within and between healthcare settings (handoffs, transfers, discharge) | Successfully improve the safety of transitions within and between healthcare settings (handoffs, transfers, discharge) | ||

| Quality and safety improvement methods and tools | Define the quality improvement methods used and infrastructure in place at one's hospital | Compare and contrast various quality improvement methods, including six sigma, lean, and PDSA | Lead a quality improvement project using six sigma, lean, or PDSA methodology |

| Summarize the basic principles and use of Root Cause Analysis as a tool to evaluate medical error | Collaborate on a quality improvement project using six sigma, lean, or PDSA | Use high level process mapping, fishbone diagrams, etc, to identify areas for opportunity in evaluating a process | |

| Describe and collaborate on Failure Mode and Effects Analysis | Lead the development and implementation of clinical protocols to standardize care delivery when appropriate | ||

| Actively participate in a Root Cause Analysis | Conduct Failure Mode and Effects Analysis | ||

| Conduct Root Cause Analysis | |||

| Health information systems | Identify the potential for information systems to reduce as well as contribute to medical error | Define types of clinical decision support | Lead or co‐lead efforts to leverage information systems in quality measurement |

| Describe how information systems fit into provider workflow and care delivery | Collaborate on the design of health information systems | Lead or co‐lead efforts to leverage information systems to reduce error and/or improve delivery of effective care | |

| Anticipate and prevent unintended consequences of implementation or revision of information systems | |||

| Lead or co‐lead efforts to leverage clinical decision support to improve quality and safety | |||

| Patient centeredness | Explain the clinical benefits of a patient‐centered approach | Explain benefits and potential limitations of patient satisfaction surveys | Interpret data from patient satisfaction surveys and lead efforts to improve patient satisfaction |

| Identify system barriers to effective and safe care from the patient's perspective | Identify clinical areas with suboptimal efficiency and/or timeliness from the patient's perspective | Lead effort to reduce inefficiency and/or improve timeliness from the patient's perspective | |

| Describe the value of patient satisfaction surveys and patient and family partnership in care | Promote patient and caregiver education including use of effective education tools | Lead efforts to eliminate system barriers to effective and safe care from the patient's perspective | |

| Lead efforts to improve patent and caregiver education including development or implementation of effective education tools | |||

| Lead efforts to actively involve patients and families in the redesign of healthcare delivery systems and processes | |||

Recommended Use of The Competencies

The HQPS Competencies provide a framework for curricula and other professional development experiences in healthcare quality and patient safety. We recommend a step‐wise approach to curriculum development which includes conducting a targeted needs assessment, defining goals and specific learning objectives, and evaluation of the curriculum.25 The HQPS Competencies can be used at each step and provide educational targets for learners across a range of interest and experience.

Professional Development

Since residency programs historically have not trained their graduates to achieve a basic level of competence, practicing hospitalists will need to seek out professional development opportunities. Some educational opportunities which already exist include the Quality Track sessions during the SHM Annual Meeting, and the SHM Quality Improvement Pre‐Course. Hospitalist leaders are currently using the HQPS Competencies to review and revise annual meeting and pre‐course objectives and content in an effort to meet the expected level of competence for SHM members. Similarly, local SHM Chapter and regional hospital medicine leaders should look to the competencies to help select topics and objectives for future presentations. Additionally, the SHM Web site offers tools to develop skills, including a resource room and quality improvement primer.26 Mentored‐implementation programs, supported by SHM, can help hospitalists' acquire more advanced experiential training in quality improvement.

New educational opportunities are being developed, including a comprehensive set of Internet‐based modules designed to help practicing hospitalists achieve a basic level of competence. Hospitalists will be able to achieve continuing medical education (CME) credit upon completion of individual modules. Plans are underway to provide Certification in Hospital Quality and Patient Safety, reflecting an advanced level of competence, upon completion of the entire set, and demonstration of knowledge and skill application through an approved quality improvement project. The certification process will leverage the success of the SHM Leadership Academies and Mentored Implementation projects to help hospitalists apply their new skills in a real world setting.

HQPS Competencies and Focused Practice in Hospital Medicine

Recently, the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) has recognized the field of hospital medicine by developing a new program that provides hospitalists the opportunity to earn Maintenance of Certification (MOC) in Internal Medicine with a Focused Practice in Hospital Medicine.27 Appropriately, hospital quality and patient safety content is included among the knowledge questions on the secure exam, and completion of a practice improvement module (commonly known as PIM) is required for the certification. The SHM Education Committee has developed a Self‐Evaluation of Medical Knowledge module related to hospital quality and patient safety for use in the MOC process. ABIM recertification with Focused Practice in Hospital Medicine is an important and visible step for the Hospital Medicine movement; the content of both the secure exam and the MOC reaffirms the notion that the acquisition of knowledge, skills, and attitudes in hospital quality and patient safety is essential to the practice of hospital medicine.

Medical Education

Because teaching hospitalists frequently serve in important roles as educators and physician leaders in quality improvement, they are often responsible for medical student and resident training in healthcare quality and patient safety. Medical schools and residency programs have struggled to integrate healthcare quality and patient safety into their curricula.11, 12, 28 Hospitalists can play a major role in academic medical centers by helping to develop curricular materials and evaluations related to healthcare quality. Though intended primarily for future and current hospitalists, the HQPS Competencies and standards for the basic level may be adapted to provide educational targets for many learners in undergraduate and graduate medical education. Teaching hospitalists may use these standards to evaluate current educational efforts and design new curricula in collaboration with their medical school and residency program leaders.

Beyond the basic level of training in healthcare quality required for all, many residents will benefit from more advanced training experiences, including opportunities to apply knowledge and develop skills related to quality improvement. A recent report from the ACGME concluded that role models and mentors were essential for engaging residents in quality improvement efforts.29 Hospitalists are ideally suited to serve as role models during residents' experiential learning opportunities related to hospital quality. Several residency programs have begun to implement hospitalist tracks13 and quality improvement rotations.3032 Additionally, some academic medical centers have begun to develop and offer fellowship training in Hospital Medicine.33 These hospitalist‐led educational programs are an ideal opportunity to teach the intermediate and advanced training components, of healthcare quality and patient safety, to residents and fellows that wish to incorporate activity or leadership in quality improvement and patient safety science into their generalist or subspecialty careers. Teaching hospitalists should use the HQPS competency standards to define learning objectives for trainees at this stage of development.

To address the enormous educational needs in quality and safety for future physicians, a cadre of expert teachers in quality and safety will need to be developed. In collaboration with the Alliance for Academic Internal Medicine (AAIM), SHM is developing a Quality and Safety Educators Academy which will target academic hospitalists and other medical educators interested in developing advanced skills in quality improvement and patient safety education.

Assessment of Competence

An essential component of a rigorous faculty development program or medical education initiative is the assessment of whether these endeavors are achieving their stated aims. Published literature provides examples of useful assessment methods applicable to the HQPS Competencies. Knowledge in several areas of HQPS competence may be assessed with the use of multiple choice tests.34, 35 Knowledge of quality improvement methods may be assessed using the Quality Improvement Knowledge Application Tool (QIKAT), an instrument in which the learner responds to each of 3 scenarios with an aim, outcome and process measures, and ideas for changes which may result in improved performance.36 Teamwork and communication skills may be assessed using 360‐degree evaluations3739 and direct observation using behaviorally anchored rating scales.4043 Objective structured clinical examinations have been used to assess knowledge and skills related to patient safety principles.44, 45 Notably, few studies have rigorously assessed the validity and reliability of tools designed to evaluate competence related to healthcare quality.46 Additionally, to our knowledge, no prior research has evaluated assessment specifically for hospitalists. Thus, the development and validation of new assessment tools based on the HQPS Competencies for learners at each level is a crucial next step in the educational process. Additionally, evaluation of educational initiatives should include analyses of clinical benefit, as the ultimate goal of these efforts is to improve patient care.47, 48

Conclusion

Hospitalists are poised to have a tremendous impact on improving the quality of care for hospitalized patients. The lack of training in quality improvement in traditional medical education programs, in which most current hospitalists were trained, can be overcome through appropriate use of the HQPS Competencies. Formal incorporation of the HQPS Competencies into professional development programs, and innovative educational initiatives and curricula, will help provide current hospitalists and the next generations of hospitalists with the needed skills to be successful.

- Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the Twenty‐first Century.Washington, DC:Institute of Medicine;2001.

- ,,,.Care in U.S. hospitals—the Hospital Quality Alliance program.N Engl J Med.2005;353(3):265–274.

- ,.Excess length of stay, charges, and mortality attributable to medical injuries during hospitalization.JAMA.2003;290(14):1868–1874.

- Hospital Compare—A quality tool provided by Medicare. Available at: http://www.hospitalcompare.hhs.gov/. Accessed April 23,2010.

- The Leapfrog Group: Hospital Quality Ratings. Available at: http://www.leapfroggroup.org/cp. Accessed April 30,2010.

- Why Not the Best? A Healthcare Quality Improvement Resource. Available at: http://www.whynotthebest.org/. Accessed April 30,2010.

- The Joint Commission: Facts about ORYX for hospitals (National Hospital Quality Measures). Available at: http://www.jointcommission.org/accreditationprograms/hospitals/oryx/oryx_facts.htm. Accessed August 19,2010.

- The Joint Commission: National Patient Safety Goals. Available at: http://www.jointcommission.org/patientsafety/nationalpatientsafetygoals/. Accessed August 9,2010.

- Hospital Acquired Conditions: Overview. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/HospitalAcqCond/01_Overview.asp. Accessed April 30,2010.

- Report to Congress:Plan to Implement a Medicare Hospital Value‐based Purchasing Program. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services, Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services;2007.

- Unmet Needs: Teaching Physicians to Provide Safe Patient Care.Boston, MA:Lucian Leape Institute at the National Patient Safety Foundation;2010.

- ,,,,.Patient safety education at U.S. and Canadian medical schools: results from the 2006 Clerkship Directors in Internal Medicine survey.Acad Med.2009;84(12):1672–1676.

- ,,,,.Fulfilling the promise of hospital medicine: tailoring internal medicine training to address hospitalists' needs.J Gen Intern Med.2008;23(7):1110–1115.

- ,,,.Hospitalists' perceptions of their residency training needs: results of a national survey.Am J Med.2001;111(3):247–254.

- ,,,,.Redesigning residency education in internal medicine: a position paper from the Association of Program Directors in Internal Medicine.Ann Intern Med.2006;144(12):920–926.

- ,,.Redesigning training for internal medicine.Ann Intern Med.2006;144(12):927–932.

- ,,,,.Core competencies in hospital medicine: development and methodology.J Hosp Med.2006;1(1):48–56.

- Intermountain Healthcare. 20‐Day Course for Executives 2001.

- ,,,.Curriculum Development for Medical Education: A Six‐step Approach.Baltimore, MD:Johns Hopkins Press;1998.