User login

Project BOOST

Enactment of federal legislation imposing hospital reimbursement penalties for excess rates of rehospitalizations among Medicare fee for service beneficiaries markedly increased interest in hospital quality improvement (QI) efforts to reduce the observed 30‐day rehospitalization of 19.6% in this elderly population.[1, 2] The Congressional Budget Office estimated that reimbursement penalties to hospitals for high readmission rates are expected to save the Medicare program approximately $7 billion between 2010 and 2019.[3] These penalties are complemented by resources from the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation aiming to reduce hospital readmissions by 20% by the end of 2013 through the Partnership for Patients campaign.[4] Although potential financial penalties and provision of resources for QI intensified efforts to enhance the quality of the hospital discharge transition, patient safety risks associated with hospital discharge are well documented.[5, 6] Approximately 20% of patients discharged from the hospital may suffer adverse events,[7, 8] of which up to three‐quarters (72%) are medication related,[9] and over one‐third of required follow‐up testing after discharge is not completed.[10] Such findings indicate opportunities for improvement in the discharge process.[11]

Numerous publications describe studies aiming to improve the hospital discharge process and mitigate these hazards, though a systematic review of interventions to reduce 30‐day rehospitalization indicated that the existing evidence base for the effectiveness of transition interventions demonstrates irregular effectiveness and limitations to generalizability.[12] Most studies showing effectiveness are confined to single academic medical centers. Existing evidence supports multifaceted interventions implemented in both the pre‐ and postdischarge periods and focused on risk assessment and tailored, patient‐centered application of interventions to mitigate risk. For example Project RED (Re‐Engineered Discharge) applied a bundled intervention consisting of intensified patient education and discharge planning, improved medication reconciliation and discharge instructions, and longitudinal patient contact with follow‐up phone calls and a dedicated discharge advocate.[13] However, the mean age of patients participating in the study was 50 years, and it excluded patients admitted from or discharged to skilled nursing facilities, making generalizability to the geriatric population uncertain.

An integral aspect of QI projects is the contribution of local context to translation of best practices to disparate settings.[14, 15, 16] Most available reports of successful interventions to reduce rehospitalization have not fully described the specifics of either the intervention context or design. Moreover, the available evidence base for common interventions to reduce rehospitalization was developed in the academic setting. Validation of single academic center studies in a broader healthcare context is necessary.

Project BOOST (Better Outcomes for Older adults through Safe Transitions) recruited a diverse national cohort of both academic and nonacademic hospitals to participate in a QI effort to implement best practices for hospital discharge care transitions using a national collaborative approach facilitated by external expert mentorship. This study aimed to determine the effectiveness of BOOST in lowering hospital readmission rates and impact on length of stay.

METHODS

The study of Project BOOST was undertaken in accordance with the SQUIRE (Standards for Quality Improvement Reporting Excellence) Guidelines.[17]

Participants

The unit of observation for the prospective cohort study was the clinical acute‐care unit within hospitals. Sites were instructed to designate a pilot unit for the intervention that cared for medical or mixed medicalsurgical patient populations. Sites were also asked to provide outcome data for a clinically and organizationally similar non‐BOOST unit to provide a site‐matched control. Control units were matched by local site leadership based on comparable patient demographics, clinical mix, and extent of housestaff presence. An initial cohort of 6 hospitals in 2008 was followed by a second cohort of 24 hospitals initiated in 2009. All hospitals were invited to participate in the national effectiveness analysis, which required submission of readmission and length of stay data for both a BOOST intervention unit and a clinically matched control unit.

Description of the Intervention

The BOOST intervention consisted of 2 major sequential processes, planning and implementation, both facilitated by external site mentorsphysicians expert in QI and care transitionsfor a period of 12 months. Extensive background on the planning and implementation components is available at

| Enrollment Sites, n=30 | Sites Reporting Outcome Data, n=11 | Sites Not Reporting Outcome Data, n=19 | P Value for Comparison of Outcome Data Sites Compared to Othersa | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Region, n (%) | 0.194 | |||

| Northeast | 8 (26.7) | 2 (18.2) | 6 (31.6) | |

| West | 7 (23.4) | 2 (18.2) | 5 (26.3) | |

| South | 7 (23.4) | 3 (27.3) | 4 (21.1) | |

| Midwest | 8 (26.7) | 4 (36.4) | 4 (21.1) | |

| Urban location, n (%) | 25 (83.3) | 11 (100) | 15 (78.9) | 0.035 |

| Teaching status, n (%) | 0.036 | |||

| Academic medical center | 10 (33.4) | 5 (45.5) | 5 (26.3) | |

| Community teaching | 8 (26.7) | 3 (27.3) | 5 (26.3) | |

| Community nonteaching | 12 (40) | 3 (27.3) | 9 (47.4) | |

| Beds number, mean (SD) | 426.6 (220.6) | 559.2 (187.8) | 349.79 (204.48) | 0.003 |

| Number of tools implemented, n (%) | 0.194 | |||

| 0 | 2 (6.7) | 0 | 2 (10.5) | |

| 1 | 2 (6.7) | 0 | 2 (10.5) | |

| 2 | 4 (13.3) | 2 (18.2) | 2 (10.5) | |

| 3 | 12 (40.0) | 3 (27.3) | 8 (42.1) | |

| 4 | 9 (30.0) | 5 (45.5) | 4 (21.1) | |

| 5 | 1 (3.3) | 1 (9.1) | 1 (5.3) | |

Mentor engagement with sites consisted of a 2‐day kickoff training on the BOOST tools, where site teams met their mentor and initiated development of structured action plans, followed by 5 to 6 scheduled phone calls in the subsequent 12 months. During these conference calls, mentors gauged progress and sought to help troubleshoot barriers to implementation. Some mentors also conducted a site visit with participant sites. Project BOOST provided sites with several collaborative activities including online webinars and an online listserv. Sites also received a quarterly newsletter.

Outcome Measures

The primary outcome was 30‐day rehospitalization defined as same hospital, all‐cause rehospitalization. Home discharges as well as discharges or transfers to other healthcare facilities were included in the discharge calculation. Elective or scheduled rehospitalizations as well as multiple rehospitalizations in the same 30‐day window were considered individual rehospitalization events. Rehospitalization was reported as a ratio of 30‐day rehospitalizations divided by live discharges in a calendar month. Length of stay was reported as the mean length of stay among live discharges in a calendar month. Outcomes were calculated at the participant site and then uploaded as overall monthly unit outcomes to a Web‐based research database.

To account for seasonal trends as well as marked variation in month‐to‐month rehospitalization rates identified in longitudinal data, we elected to compare 3‐month year‐over‐year averages to determine relative changes in readmission rates from the period prior to BOOST implementation to the period after BOOST implementation. We calculated averages for rehospitalization and length of stay in the 3‐month period preceding the sites' first reported month of front‐line implementation and in the corresponding 3‐month period in the subsequent calendar year. For example, if a site reported implementing its first tool in April 2010, the average readmission rate in the unit for January 2011 through March 2011 was subtracted from the average readmission rate for January 2010 through March 2010.

Sites were surveyed regarding tool implementation rates 6 months and 24 months after the 2009 kickoff training session. Surveys were electronically completed by site leaders in consultation with site team members. The survey identified new tool implementation as well as modification of existing care processes using the BOOST tools (admission risk assessment, discharge readiness checklist, teach back use, mandate regarding discharge summary completion, follow‐up phone calls to >80% of discharges). Use of a sixth tool, creation of individualized written discharge instructions, was not measured. We credited sites with tool implementation if they reported either de novo tool use or alteration of previous care processes influenced by BOOST tools.

Clinical outcome reporting was voluntary, and sites did not receive compensation and were not subject to penalty for the degree of implementation or outcome reporting. No patient‐level information was collected for the analysis, which was approved by the Northwestern University institutional review board.

Data Sources and Methods

Readmission and length of stay data, including the unit level readmission rate, as collected from administrative sources at each hospital, were collected using templated spreadsheet software between December 2008 and June 2010, after which data were loaded directly to a Web‐based data‐tracking platform. Sites were asked to load data as they became available. Sites were asked to report the number of study unit discharges as well as the number of those discharges readmitted within 30 days; however, reporting of the number of patient discharges was inconsistent across sites. Serial outreach consisting of monthly phone calls or email messaging to site leaders was conducted throughout 2011 to increase site participation in the project analysis.

Implementation date information was collected from 2 sources. The first was through online surveys distributed in November 2009 and April 2011. The second was through fields in the Web‐based data tracking platform to which sites uploaded data. In cases where disagreement was found between these 2 sources, the site leader was contacted for clarification.

Practice setting (community teaching, community nonteaching, academic medical center) was determined by site‐leader report within the Web‐based data tracking platform. Data for hospital characteristics (number of licensed beds and geographic region) were obtained from the American Hospital Association's Annual Survey of Hospitals.[18] Hospital region was characterized as West, South, Midwest, or Northeast.

Analysis

The null hypothesis was that no prepost difference existed in readmission rates within BOOST units, and no difference existed in the prepost change in readmission rates in BOOST units when compared to site‐matched control units. The Wilcoxon rank sum test was used to test whether observed changes described above were significantly different from 0, supporting rejection of the null hypotheses. We performed similar tests to determine the significance of observed changes in length of stay. We performed our analysis using SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Eleven hospitals provided rehospitalization and length‐of‐stay outcome data for both a BOOST and control unit for the pre‐ and postimplementation periods. Compared to the 19 sites that did not participate in the analysis, these 11 sites were significantly larger (559188 beds vs 350205 beds, P=0.003), more likely to be located in an urban area (100.0% [n=11] vs 78.9% [n=15], P=0.035), and more likely to be academic medical centers (45.5% [n=5] vs 26.3% [n=5], P=0.036) (Table 1).

The mean number of tools implemented by sites participating in the analysis was 3.50.9. All sites implemented at least 2 tools. The duration between attendance at the BOOST kickoff event and first tool implementation ranged from 3 months (first tool implemented prior to attending the kickoff) and 9 months (mean duration, 3.34.3 months) (Table 2).

| Hospital | Region | Hospital Type | No. Licensed Beds | Kickoff Implementationa | Risk Assessment | Discharge Checklist | Teach Back | Discharge Summary Completion | Follow‐up Phone Call | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||

| 1 | Midwest | Community teaching | <300 | 8 | 3 | |||||

| 2 | West | Community teaching | >600 | 0 | 4 | |||||

| 3 | Northeast | Academic medical center | >600 | 2 | 4 | |||||

| 4 | Northeast | Community nonteaching | <300 | 9 | 2 | |||||

| 5 | South | Community nonteaching | >600 | 6 | 3 | |||||

| 6 | South | Community nonteaching | >600 | 3 | 4 | |||||

| 7 | Midwest | Community teaching | 300600 | 1 | 5 | |||||

| 8 | West | Academic medical center | 300600 | 1 | 4 | |||||

| 9 | South | Academic medical center | >600 | 4 | 4 | |||||

| 10 | Midwest | Academic medical center | 300600 | 3 | 3 | |||||

| 11 | Midwest | Academic medical center | >600 | 9 | 2 | |||||

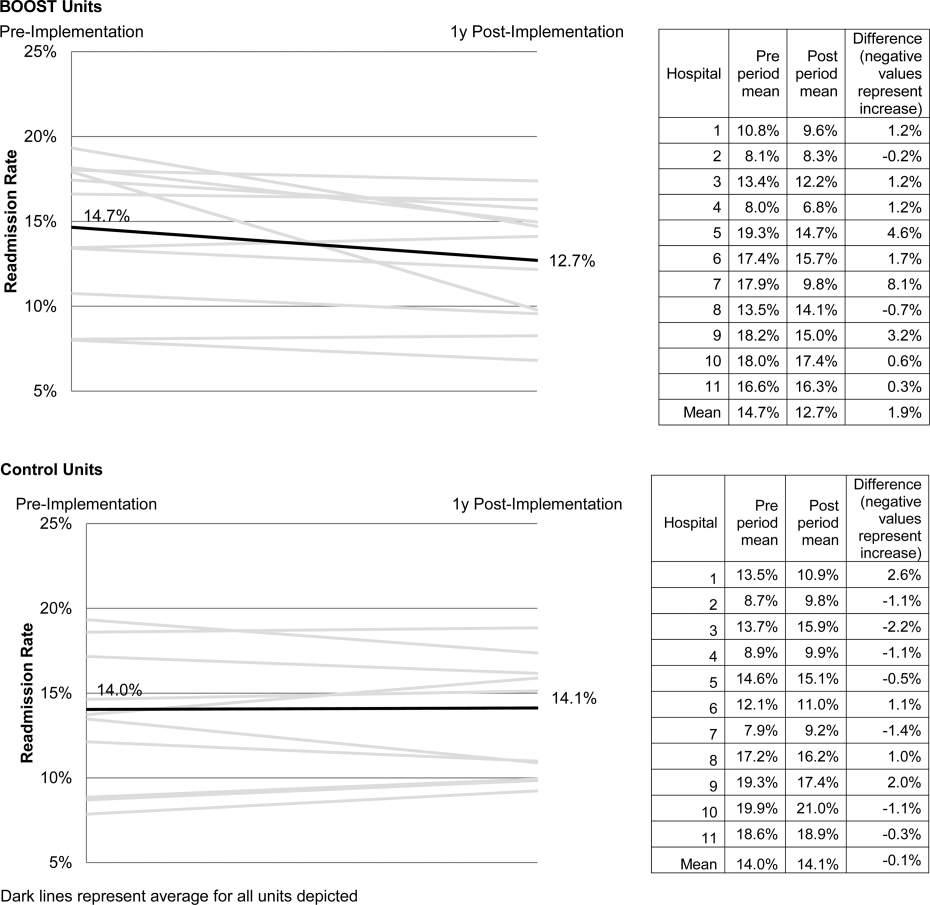

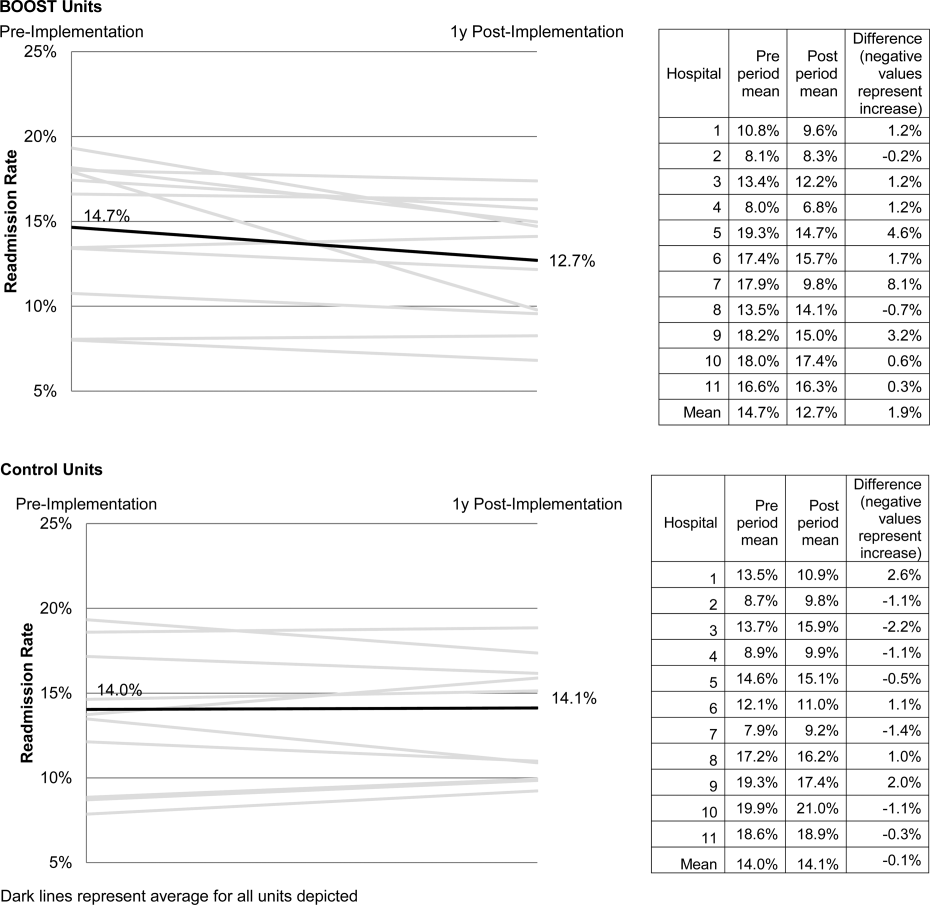

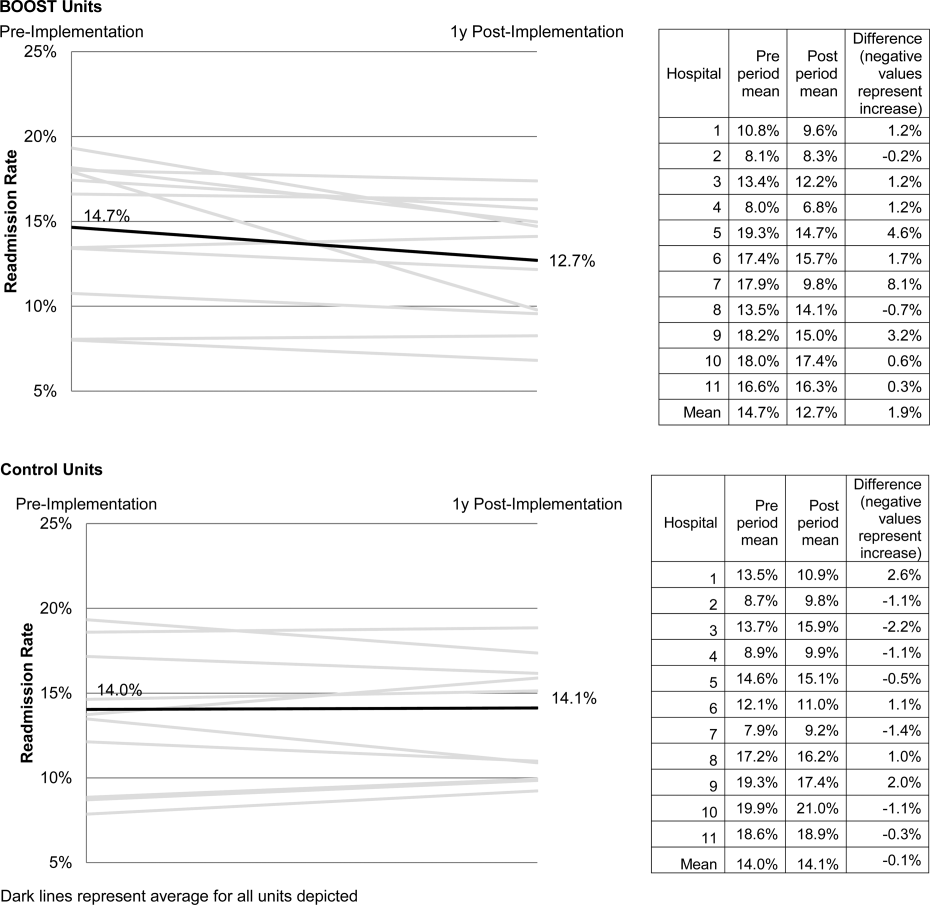

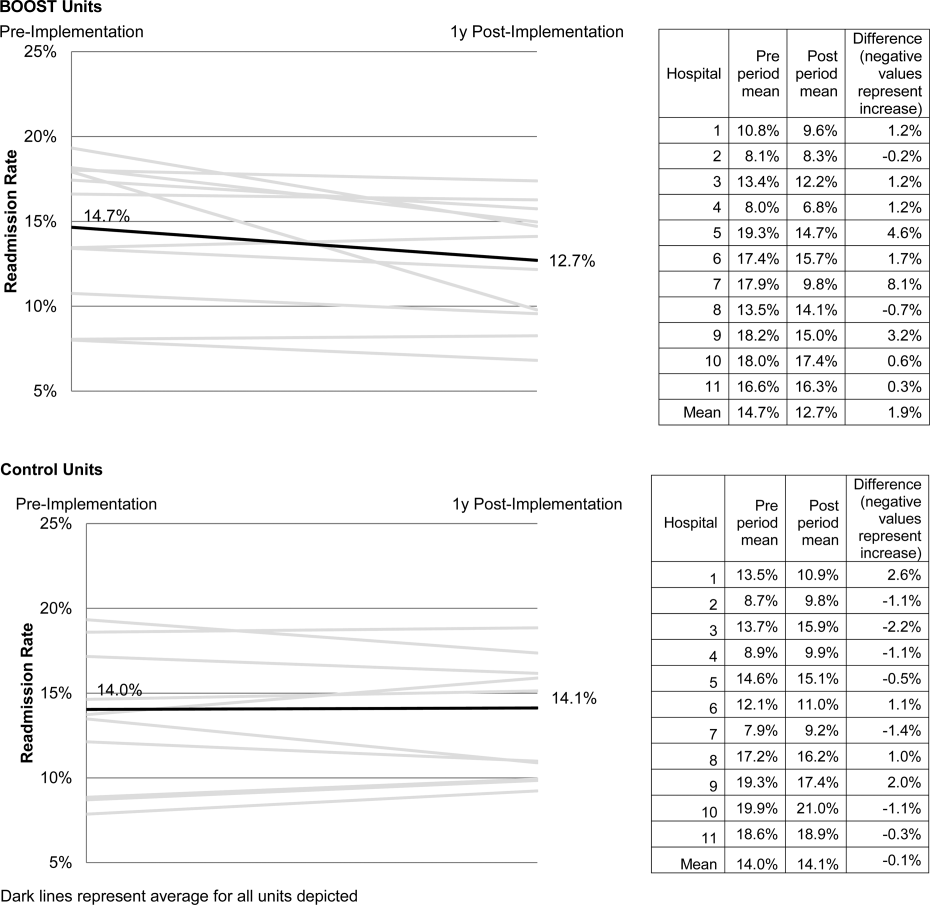

The average rate of 30‐day rehospitalization among BOOST units was 14.7% in the preimplementation period and 12.7% during the postimplementation period (P=0.010) (Figure 1). Rehospitalization rates for matched control units were 14.0% in the preintervention period and 14.1% in the postintervention period (P=0.831). The mean absolute reduction in readmission rates over the 1‐year study period in BOOST units compared to control units was 2.0%, or a relative reduction of 13.6% (P=0.054 for signed rank test comparing differences in readmission rate reduction in BOOST units compared to site‐matched control units). Length of stay in BOOST and control units decreased an average of 0.5 days and 0.3 days, respectively. There was no difference in length of stay change between BOOST units and control units (P=0.966).

DISCUSSION

As hospitals strive to reduce their readmission rates to avoid Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services penalties, Project BOOST may be a viable QI approach to achieve their goals. This initial evaluation of participation in Project BOOST by 11 hospitals of varying sizes across the United States showed an associated reduction in rehospitalization rates (absolute=2.0% and relative=13.6%, P=0.054). We did not find any significant change in length of stay among these hospitals implementing BOOST tools.

The tools provided to participating hospitals were developed from evidence found in peer‐reviewed literature established through experimental methods in well‐controlled academic settings. Further tool development was informed by recommendations of an advisory board consisting of expert representatives and advocates involved in the hospital discharge process: patients, caregivers, physicians, nurses, case managers, social workers, insurers, and regulatory and research agencies.[19] The toolkit components address multiple aspects of hospital discharge and follow‐up with the goal of improving health by optimizing the safety of care transitions. Our observation that readmission rates appeared to improve in a diverse hospital sample including nonacademic and community hospitals engaged in Project BOOST is reassuring that the benefits seen in existing research literature, developed in distinctly academic settings, can be replicated in diverse acute‐care settings.

The effect size observed in our study was modest but consistent with several studies identified in a recent review of trials measuring interventions to reduce rehospitalization, where 7 of 16 studies showing a significant improvement registered change in the 0% to 5% absolute range.[12] Impact of this project may have been tempered by the need to translate external QI content to the local setting. Additionally, in contrast to experimental studies that are limited in scope and timing and often scaled to a research budget, BOOST sites were encouraged to implement Project BOOST in the clinical setting even if no new funds were available to support the effort.[12]

The recruitment of a national sample of both academic and nonacademic hospital participants imposed several limitations on our study and analysis. We recognize that intervention units selected by hospitals may have had unmeasured unit and patient characteristics that facilitated successful change and contributed to the observed improvements. However, because external pressure to reduce readmission is present across all hospitals independent of the BOOST intervention, we felt site‐matched controls were essential to understanding effects attributable to the BOOST tools. Differences between units would be expected to be stable over the course of the study period, and comparison of outcome differences between 2 different time periods would be reasonable. Additionally, we could not collect data on readmissions to other hospitals. Theoretically, patients discharged from BOOST units might be more likely to have been rehospitalized elsewhere, but the fraction of rehospitalizations occurring at alternate facilities would also be expected to be similar on the matched control unit.

We report findings from a voluntary cohort willing and capable of designating a comparison clinical unit and contributing the requested data outcomes. Pilot sites that did not report outcomes were not analyzed, but comparison of hospital characteristics shows that participating hospitals were more likely to be large, urban, academic medical centers. Although barriers to data submission were not formally analyzed, reports from nonparticipating sites describe data submission limited by local implementation design (no geographic rollout or simultaneous rollout on all appropriate clinical units), site specific inability to generate unit level outcome statistics, and competing organizational priorities for data analyst time (electronic medical record deployment, alternative QI initiatives). The external validity of our results may be limited to organizations capable of analytics at the level of the individual clinical unit as well as those with sufficient QI resources to support reporting to a national database in the absence of a payer mandate. It is possible that additional financial support for on‐site data collection would have bolstered participation, making the example of participation rates we present potentially informative to organizations hoping to widely disseminate a QI agenda.

Nonetheless, the effectiveness demonstrated in the 11 sites that did participate is encouraging, and ongoing collaboration with subsequent BOOST cohorts has been designed to further facilitate data collection. Among the insights gained from this pilot experience, and incorporated into ongoing BOOST cohorts, is the importance of intensive mentor engagement to foster accountability among participant sites, assist with implementation troubleshooting, and offer expertise that is often particularly effective in gaining local support. We now encourage sites to have 2 mentor site visits to further these roles and more frequent conference calls. Further research to understand the marginal benefit of the mentored implementation approach is ongoing.

The limitations in data submission we experienced with the pilot cohort likely reflect resource constraints not uncommon at many hospitals. Increasing pressure placed on hospitals as a result of the Readmission Reduction Program within the Affordable Care Act as well as increasing interest from private and Medicaid payors to incorporate similar readmission‐based penalties provide encouragement for hospitals to enhance their data and analytic skills. National incentives for implementation of electronic health records (EHR) should also foster such capabilities, though we often saw EHRs as a barrier to QI, especially rapid cycle trials. Fortunately, hospitals are increasingly being afforded access to comprehensive claims databases to assist in tracking readmission rates to other facilities, and these data are becoming available in a more timely fashion. This more robust data collection, facilitated by private payors, state QI organizations, and state hospital associations, will support additional analytic methods such as multivariate regression models and interrupted time series designs to appreciate the experience of current BOOST participants.

Additional research is needed to understand the role of organizational context in the effectiveness of Project BOOST. Differences in rates of tool implementation and changes in clinical outcomes are likely dependent on local implementation context at the level of the healthcare organization and individual clinical unit.[20] Progress reports from site mentors and previously described experiences of QI implementation indicate that successful implementation of a multidimensional bundle of interventions may have reflected a higher level of institutional support, more robust team engagement in the work of reducing readmissions, increased clinical staff support for change, the presence of an effective project champion, or a key facilitating role of external mentorship.[21, 22] Ongoing data collection will continue to measure the sustainability of tool use and observed outcome changes to inform strategies to maintain gains associated with implementation. The role of mentored implementation in facilitating gains also requires further study.

Increasing attention to the problem of avoidable rehospitalization is driving hospitals, insurers, and policy makers to pursue QI efforts that favorably impact readmission rates. Our analysis of the BOOST intervention suggests that modest gains can be achieved following evidence‐based hospital process change facilitated by a mentored implementation model. However, realization of the goal of a 20% reduction in rehospitalization proposed by the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services' Partnership for Patients initiative may be difficult to achieve on a national scale,[23] especially if efforts focus on just the hospital.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the contributions of Amanda Creden, BA (data collection), Julia Lee (biostatistical support), and the support of Amy Berman, BS, RN, Senior Program Officer at The John A. Hartford Foundation.

Disclosures

Project BOOST was funded by a grant from The John A. Hartford Foundation. Project BOOST is administered by the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM). The development of the Project BOOST toolkit, recruitment of sites for this study, mentorship of the pilot cohort, project evaluation planning, and collection of pilot data were funded by a grant from The John A. Harford Foundation. Additional funding for continued data collection and analysis was funded by the SHM through funds from hospitals to participate in Project BOOST, specifically with funding support for Dr. Hansen. Dr. Williams has received funding to serve as Principal Investigator for Project BOOST. Since the time of initial cohort participation, approximately 125 additional hospitals have participated in the mentored implementation of Project BOOST. This participation was funded through a combination of site‐based tuition, third‐party payor support from private insurers, foundations, and federal funding through the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation Partnership for Patients program. Drs. Greenwald, Hansen, and Williams are Project BOOST mentors for current Project BOOST sites and receive financial support through the SHM for this work. Dr. Howell has previously received funding as a Project BOOST mentor. Ms. Budnitz is the BOOST Project Director and is Chief Strategy and Development Officer for the HM. Dr. Maynard is the Senior Vice President of the SHM's Center for Hospital Innovation and Improvement.

References

- , , . Rehospitalizations among patients in the Medicare fee‐for‐service program. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(14):1418–1428.

- United States Congress. House Committee on Education and Labor. Coe on Ways and Means, Committee on Energy and Commerce, Compilation of Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act: as amended through November 1, 2010 including Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act health‐related portions of the Health Care and Education Reconciliation Act of 2010. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office; 2010.

- Cost estimate for the amendment in the nature of a substitute to H.R. 3590, as proposed in the Senate on November 18, 2009. Washington, DC: Congressional Budget Office; 2009.

- Partnership for Patients, Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation. Available at: http://www.innovations.cms.gov/initiatives/Partnership‐for‐Patients/index.html. Accessed December 12, 2012.

- , . Providers have failed to work for continuity. Hospitals. 1979;53(10):79.

- , . Executing high‐quality care transitions: a call to do it right. J Hosp Med. 2007;2(5):287–290.

- , , , , . The incidence and severity of adverse events affecting patients after discharge from the hospital. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138(3):161–167.

- , , , et al. Adverse events among medical patients after discharge from hospital. CMAJ. 2004;170(3):345–349.

- , , , et al. Making inpatient medication reconciliation patient centered, clinically relevant and implementable: a consensus statement on key principles and necessary first steps. J Hosp Med. 2010;5(8):477–485.

- , , . Tying up loose ends: discharging patients with unresolved medical issues. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(12):1305.

- , , , , , . Deficits in communication and information transfer between hospital‐based and primary care physicians. JAMA. 2007;297(8):831–841.

- , , , , . Interventions to reduce 30‐day rehospitalization: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(8):520–528.

- , , , et al. A reengineered hospital discharge program to decrease rehospitalization: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150(3):178.

- , , , et al. Advancing the science of patient safety. Ann Intern Med. 2011;154(10):693–696.

- , . From best evidence to best practice: effective implementation of change in patients' care. Lancet. 2003;362(9391):1225–1230.

- , , , et al. Quality improvement projects targeting health care‐associated infections: comparing virtual collaborative and toolkit approaches. J Hosp Med. 2011;6(5):271–278.

- , , , , . Publication guidelines for improvement studies in health care: evolution of the SQUIRE project. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149(9):670–676.

- , , , . Risk stratification and therapeutic decision making in acute coronary syndromes. JAMA. 2000;284(7):876–878.

- , , . Are diagnosis specific outcome indicators based on administrative data useful in assessing quality of hospital care? BMJ. 2004;13(1):32.

- , , , et al. What distinguishes top‐performing hospitals in acute myocardial infarction mortality rates? Ann Intern Med. 2011;154(6):384–390.

- , , , . The Model for Understanding Success in Quality (MUSIQ): building a theory of context in healthcare quality improvement. BMJ Qual Saf. 2012;21(1):13–20.

- , . Evidence‐based quality improvement: the state of the science. Health Aff (Millwood). 2005;24(1):138–150.

- Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation. Partnership for patients. Available at: http://www.innovations.cms.gov/initiatives/Partnership‐for‐Patients/index.html. Accessed April 2, 2012.

Enactment of federal legislation imposing hospital reimbursement penalties for excess rates of rehospitalizations among Medicare fee for service beneficiaries markedly increased interest in hospital quality improvement (QI) efforts to reduce the observed 30‐day rehospitalization of 19.6% in this elderly population.[1, 2] The Congressional Budget Office estimated that reimbursement penalties to hospitals for high readmission rates are expected to save the Medicare program approximately $7 billion between 2010 and 2019.[3] These penalties are complemented by resources from the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation aiming to reduce hospital readmissions by 20% by the end of 2013 through the Partnership for Patients campaign.[4] Although potential financial penalties and provision of resources for QI intensified efforts to enhance the quality of the hospital discharge transition, patient safety risks associated with hospital discharge are well documented.[5, 6] Approximately 20% of patients discharged from the hospital may suffer adverse events,[7, 8] of which up to three‐quarters (72%) are medication related,[9] and over one‐third of required follow‐up testing after discharge is not completed.[10] Such findings indicate opportunities for improvement in the discharge process.[11]

Numerous publications describe studies aiming to improve the hospital discharge process and mitigate these hazards, though a systematic review of interventions to reduce 30‐day rehospitalization indicated that the existing evidence base for the effectiveness of transition interventions demonstrates irregular effectiveness and limitations to generalizability.[12] Most studies showing effectiveness are confined to single academic medical centers. Existing evidence supports multifaceted interventions implemented in both the pre‐ and postdischarge periods and focused on risk assessment and tailored, patient‐centered application of interventions to mitigate risk. For example Project RED (Re‐Engineered Discharge) applied a bundled intervention consisting of intensified patient education and discharge planning, improved medication reconciliation and discharge instructions, and longitudinal patient contact with follow‐up phone calls and a dedicated discharge advocate.[13] However, the mean age of patients participating in the study was 50 years, and it excluded patients admitted from or discharged to skilled nursing facilities, making generalizability to the geriatric population uncertain.

An integral aspect of QI projects is the contribution of local context to translation of best practices to disparate settings.[14, 15, 16] Most available reports of successful interventions to reduce rehospitalization have not fully described the specifics of either the intervention context or design. Moreover, the available evidence base for common interventions to reduce rehospitalization was developed in the academic setting. Validation of single academic center studies in a broader healthcare context is necessary.

Project BOOST (Better Outcomes for Older adults through Safe Transitions) recruited a diverse national cohort of both academic and nonacademic hospitals to participate in a QI effort to implement best practices for hospital discharge care transitions using a national collaborative approach facilitated by external expert mentorship. This study aimed to determine the effectiveness of BOOST in lowering hospital readmission rates and impact on length of stay.

METHODS

The study of Project BOOST was undertaken in accordance with the SQUIRE (Standards for Quality Improvement Reporting Excellence) Guidelines.[17]

Participants

The unit of observation for the prospective cohort study was the clinical acute‐care unit within hospitals. Sites were instructed to designate a pilot unit for the intervention that cared for medical or mixed medicalsurgical patient populations. Sites were also asked to provide outcome data for a clinically and organizationally similar non‐BOOST unit to provide a site‐matched control. Control units were matched by local site leadership based on comparable patient demographics, clinical mix, and extent of housestaff presence. An initial cohort of 6 hospitals in 2008 was followed by a second cohort of 24 hospitals initiated in 2009. All hospitals were invited to participate in the national effectiveness analysis, which required submission of readmission and length of stay data for both a BOOST intervention unit and a clinically matched control unit.

Description of the Intervention

The BOOST intervention consisted of 2 major sequential processes, planning and implementation, both facilitated by external site mentorsphysicians expert in QI and care transitionsfor a period of 12 months. Extensive background on the planning and implementation components is available at

| Enrollment Sites, n=30 | Sites Reporting Outcome Data, n=11 | Sites Not Reporting Outcome Data, n=19 | P Value for Comparison of Outcome Data Sites Compared to Othersa | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Region, n (%) | 0.194 | |||

| Northeast | 8 (26.7) | 2 (18.2) | 6 (31.6) | |

| West | 7 (23.4) | 2 (18.2) | 5 (26.3) | |

| South | 7 (23.4) | 3 (27.3) | 4 (21.1) | |

| Midwest | 8 (26.7) | 4 (36.4) | 4 (21.1) | |

| Urban location, n (%) | 25 (83.3) | 11 (100) | 15 (78.9) | 0.035 |

| Teaching status, n (%) | 0.036 | |||

| Academic medical center | 10 (33.4) | 5 (45.5) | 5 (26.3) | |

| Community teaching | 8 (26.7) | 3 (27.3) | 5 (26.3) | |

| Community nonteaching | 12 (40) | 3 (27.3) | 9 (47.4) | |

| Beds number, mean (SD) | 426.6 (220.6) | 559.2 (187.8) | 349.79 (204.48) | 0.003 |

| Number of tools implemented, n (%) | 0.194 | |||

| 0 | 2 (6.7) | 0 | 2 (10.5) | |

| 1 | 2 (6.7) | 0 | 2 (10.5) | |

| 2 | 4 (13.3) | 2 (18.2) | 2 (10.5) | |

| 3 | 12 (40.0) | 3 (27.3) | 8 (42.1) | |

| 4 | 9 (30.0) | 5 (45.5) | 4 (21.1) | |

| 5 | 1 (3.3) | 1 (9.1) | 1 (5.3) | |

Mentor engagement with sites consisted of a 2‐day kickoff training on the BOOST tools, where site teams met their mentor and initiated development of structured action plans, followed by 5 to 6 scheduled phone calls in the subsequent 12 months. During these conference calls, mentors gauged progress and sought to help troubleshoot barriers to implementation. Some mentors also conducted a site visit with participant sites. Project BOOST provided sites with several collaborative activities including online webinars and an online listserv. Sites also received a quarterly newsletter.

Outcome Measures

The primary outcome was 30‐day rehospitalization defined as same hospital, all‐cause rehospitalization. Home discharges as well as discharges or transfers to other healthcare facilities were included in the discharge calculation. Elective or scheduled rehospitalizations as well as multiple rehospitalizations in the same 30‐day window were considered individual rehospitalization events. Rehospitalization was reported as a ratio of 30‐day rehospitalizations divided by live discharges in a calendar month. Length of stay was reported as the mean length of stay among live discharges in a calendar month. Outcomes were calculated at the participant site and then uploaded as overall monthly unit outcomes to a Web‐based research database.

To account for seasonal trends as well as marked variation in month‐to‐month rehospitalization rates identified in longitudinal data, we elected to compare 3‐month year‐over‐year averages to determine relative changes in readmission rates from the period prior to BOOST implementation to the period after BOOST implementation. We calculated averages for rehospitalization and length of stay in the 3‐month period preceding the sites' first reported month of front‐line implementation and in the corresponding 3‐month period in the subsequent calendar year. For example, if a site reported implementing its first tool in April 2010, the average readmission rate in the unit for January 2011 through March 2011 was subtracted from the average readmission rate for January 2010 through March 2010.

Sites were surveyed regarding tool implementation rates 6 months and 24 months after the 2009 kickoff training session. Surveys were electronically completed by site leaders in consultation with site team members. The survey identified new tool implementation as well as modification of existing care processes using the BOOST tools (admission risk assessment, discharge readiness checklist, teach back use, mandate regarding discharge summary completion, follow‐up phone calls to >80% of discharges). Use of a sixth tool, creation of individualized written discharge instructions, was not measured. We credited sites with tool implementation if they reported either de novo tool use or alteration of previous care processes influenced by BOOST tools.

Clinical outcome reporting was voluntary, and sites did not receive compensation and were not subject to penalty for the degree of implementation or outcome reporting. No patient‐level information was collected for the analysis, which was approved by the Northwestern University institutional review board.

Data Sources and Methods

Readmission and length of stay data, including the unit level readmission rate, as collected from administrative sources at each hospital, were collected using templated spreadsheet software between December 2008 and June 2010, after which data were loaded directly to a Web‐based data‐tracking platform. Sites were asked to load data as they became available. Sites were asked to report the number of study unit discharges as well as the number of those discharges readmitted within 30 days; however, reporting of the number of patient discharges was inconsistent across sites. Serial outreach consisting of monthly phone calls or email messaging to site leaders was conducted throughout 2011 to increase site participation in the project analysis.

Implementation date information was collected from 2 sources. The first was through online surveys distributed in November 2009 and April 2011. The second was through fields in the Web‐based data tracking platform to which sites uploaded data. In cases where disagreement was found between these 2 sources, the site leader was contacted for clarification.

Practice setting (community teaching, community nonteaching, academic medical center) was determined by site‐leader report within the Web‐based data tracking platform. Data for hospital characteristics (number of licensed beds and geographic region) were obtained from the American Hospital Association's Annual Survey of Hospitals.[18] Hospital region was characterized as West, South, Midwest, or Northeast.

Analysis

The null hypothesis was that no prepost difference existed in readmission rates within BOOST units, and no difference existed in the prepost change in readmission rates in BOOST units when compared to site‐matched control units. The Wilcoxon rank sum test was used to test whether observed changes described above were significantly different from 0, supporting rejection of the null hypotheses. We performed similar tests to determine the significance of observed changes in length of stay. We performed our analysis using SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Eleven hospitals provided rehospitalization and length‐of‐stay outcome data for both a BOOST and control unit for the pre‐ and postimplementation periods. Compared to the 19 sites that did not participate in the analysis, these 11 sites were significantly larger (559188 beds vs 350205 beds, P=0.003), more likely to be located in an urban area (100.0% [n=11] vs 78.9% [n=15], P=0.035), and more likely to be academic medical centers (45.5% [n=5] vs 26.3% [n=5], P=0.036) (Table 1).

The mean number of tools implemented by sites participating in the analysis was 3.50.9. All sites implemented at least 2 tools. The duration between attendance at the BOOST kickoff event and first tool implementation ranged from 3 months (first tool implemented prior to attending the kickoff) and 9 months (mean duration, 3.34.3 months) (Table 2).

| Hospital | Region | Hospital Type | No. Licensed Beds | Kickoff Implementationa | Risk Assessment | Discharge Checklist | Teach Back | Discharge Summary Completion | Follow‐up Phone Call | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||

| 1 | Midwest | Community teaching | <300 | 8 | 3 | |||||

| 2 | West | Community teaching | >600 | 0 | 4 | |||||

| 3 | Northeast | Academic medical center | >600 | 2 | 4 | |||||

| 4 | Northeast | Community nonteaching | <300 | 9 | 2 | |||||

| 5 | South | Community nonteaching | >600 | 6 | 3 | |||||

| 6 | South | Community nonteaching | >600 | 3 | 4 | |||||

| 7 | Midwest | Community teaching | 300600 | 1 | 5 | |||||

| 8 | West | Academic medical center | 300600 | 1 | 4 | |||||

| 9 | South | Academic medical center | >600 | 4 | 4 | |||||

| 10 | Midwest | Academic medical center | 300600 | 3 | 3 | |||||

| 11 | Midwest | Academic medical center | >600 | 9 | 2 | |||||

The average rate of 30‐day rehospitalization among BOOST units was 14.7% in the preimplementation period and 12.7% during the postimplementation period (P=0.010) (Figure 1). Rehospitalization rates for matched control units were 14.0% in the preintervention period and 14.1% in the postintervention period (P=0.831). The mean absolute reduction in readmission rates over the 1‐year study period in BOOST units compared to control units was 2.0%, or a relative reduction of 13.6% (P=0.054 for signed rank test comparing differences in readmission rate reduction in BOOST units compared to site‐matched control units). Length of stay in BOOST and control units decreased an average of 0.5 days and 0.3 days, respectively. There was no difference in length of stay change between BOOST units and control units (P=0.966).

DISCUSSION

As hospitals strive to reduce their readmission rates to avoid Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services penalties, Project BOOST may be a viable QI approach to achieve their goals. This initial evaluation of participation in Project BOOST by 11 hospitals of varying sizes across the United States showed an associated reduction in rehospitalization rates (absolute=2.0% and relative=13.6%, P=0.054). We did not find any significant change in length of stay among these hospitals implementing BOOST tools.

The tools provided to participating hospitals were developed from evidence found in peer‐reviewed literature established through experimental methods in well‐controlled academic settings. Further tool development was informed by recommendations of an advisory board consisting of expert representatives and advocates involved in the hospital discharge process: patients, caregivers, physicians, nurses, case managers, social workers, insurers, and regulatory and research agencies.[19] The toolkit components address multiple aspects of hospital discharge and follow‐up with the goal of improving health by optimizing the safety of care transitions. Our observation that readmission rates appeared to improve in a diverse hospital sample including nonacademic and community hospitals engaged in Project BOOST is reassuring that the benefits seen in existing research literature, developed in distinctly academic settings, can be replicated in diverse acute‐care settings.

The effect size observed in our study was modest but consistent with several studies identified in a recent review of trials measuring interventions to reduce rehospitalization, where 7 of 16 studies showing a significant improvement registered change in the 0% to 5% absolute range.[12] Impact of this project may have been tempered by the need to translate external QI content to the local setting. Additionally, in contrast to experimental studies that are limited in scope and timing and often scaled to a research budget, BOOST sites were encouraged to implement Project BOOST in the clinical setting even if no new funds were available to support the effort.[12]

The recruitment of a national sample of both academic and nonacademic hospital participants imposed several limitations on our study and analysis. We recognize that intervention units selected by hospitals may have had unmeasured unit and patient characteristics that facilitated successful change and contributed to the observed improvements. However, because external pressure to reduce readmission is present across all hospitals independent of the BOOST intervention, we felt site‐matched controls were essential to understanding effects attributable to the BOOST tools. Differences between units would be expected to be stable over the course of the study period, and comparison of outcome differences between 2 different time periods would be reasonable. Additionally, we could not collect data on readmissions to other hospitals. Theoretically, patients discharged from BOOST units might be more likely to have been rehospitalized elsewhere, but the fraction of rehospitalizations occurring at alternate facilities would also be expected to be similar on the matched control unit.

We report findings from a voluntary cohort willing and capable of designating a comparison clinical unit and contributing the requested data outcomes. Pilot sites that did not report outcomes were not analyzed, but comparison of hospital characteristics shows that participating hospitals were more likely to be large, urban, academic medical centers. Although barriers to data submission were not formally analyzed, reports from nonparticipating sites describe data submission limited by local implementation design (no geographic rollout or simultaneous rollout on all appropriate clinical units), site specific inability to generate unit level outcome statistics, and competing organizational priorities for data analyst time (electronic medical record deployment, alternative QI initiatives). The external validity of our results may be limited to organizations capable of analytics at the level of the individual clinical unit as well as those with sufficient QI resources to support reporting to a national database in the absence of a payer mandate. It is possible that additional financial support for on‐site data collection would have bolstered participation, making the example of participation rates we present potentially informative to organizations hoping to widely disseminate a QI agenda.

Nonetheless, the effectiveness demonstrated in the 11 sites that did participate is encouraging, and ongoing collaboration with subsequent BOOST cohorts has been designed to further facilitate data collection. Among the insights gained from this pilot experience, and incorporated into ongoing BOOST cohorts, is the importance of intensive mentor engagement to foster accountability among participant sites, assist with implementation troubleshooting, and offer expertise that is often particularly effective in gaining local support. We now encourage sites to have 2 mentor site visits to further these roles and more frequent conference calls. Further research to understand the marginal benefit of the mentored implementation approach is ongoing.

The limitations in data submission we experienced with the pilot cohort likely reflect resource constraints not uncommon at many hospitals. Increasing pressure placed on hospitals as a result of the Readmission Reduction Program within the Affordable Care Act as well as increasing interest from private and Medicaid payors to incorporate similar readmission‐based penalties provide encouragement for hospitals to enhance their data and analytic skills. National incentives for implementation of electronic health records (EHR) should also foster such capabilities, though we often saw EHRs as a barrier to QI, especially rapid cycle trials. Fortunately, hospitals are increasingly being afforded access to comprehensive claims databases to assist in tracking readmission rates to other facilities, and these data are becoming available in a more timely fashion. This more robust data collection, facilitated by private payors, state QI organizations, and state hospital associations, will support additional analytic methods such as multivariate regression models and interrupted time series designs to appreciate the experience of current BOOST participants.

Additional research is needed to understand the role of organizational context in the effectiveness of Project BOOST. Differences in rates of tool implementation and changes in clinical outcomes are likely dependent on local implementation context at the level of the healthcare organization and individual clinical unit.[20] Progress reports from site mentors and previously described experiences of QI implementation indicate that successful implementation of a multidimensional bundle of interventions may have reflected a higher level of institutional support, more robust team engagement in the work of reducing readmissions, increased clinical staff support for change, the presence of an effective project champion, or a key facilitating role of external mentorship.[21, 22] Ongoing data collection will continue to measure the sustainability of tool use and observed outcome changes to inform strategies to maintain gains associated with implementation. The role of mentored implementation in facilitating gains also requires further study.

Increasing attention to the problem of avoidable rehospitalization is driving hospitals, insurers, and policy makers to pursue QI efforts that favorably impact readmission rates. Our analysis of the BOOST intervention suggests that modest gains can be achieved following evidence‐based hospital process change facilitated by a mentored implementation model. However, realization of the goal of a 20% reduction in rehospitalization proposed by the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services' Partnership for Patients initiative may be difficult to achieve on a national scale,[23] especially if efforts focus on just the hospital.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the contributions of Amanda Creden, BA (data collection), Julia Lee (biostatistical support), and the support of Amy Berman, BS, RN, Senior Program Officer at The John A. Hartford Foundation.

Disclosures

Project BOOST was funded by a grant from The John A. Hartford Foundation. Project BOOST is administered by the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM). The development of the Project BOOST toolkit, recruitment of sites for this study, mentorship of the pilot cohort, project evaluation planning, and collection of pilot data were funded by a grant from The John A. Harford Foundation. Additional funding for continued data collection and analysis was funded by the SHM through funds from hospitals to participate in Project BOOST, specifically with funding support for Dr. Hansen. Dr. Williams has received funding to serve as Principal Investigator for Project BOOST. Since the time of initial cohort participation, approximately 125 additional hospitals have participated in the mentored implementation of Project BOOST. This participation was funded through a combination of site‐based tuition, third‐party payor support from private insurers, foundations, and federal funding through the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation Partnership for Patients program. Drs. Greenwald, Hansen, and Williams are Project BOOST mentors for current Project BOOST sites and receive financial support through the SHM for this work. Dr. Howell has previously received funding as a Project BOOST mentor. Ms. Budnitz is the BOOST Project Director and is Chief Strategy and Development Officer for the HM. Dr. Maynard is the Senior Vice President of the SHM's Center for Hospital Innovation and Improvement.

References

Enactment of federal legislation imposing hospital reimbursement penalties for excess rates of rehospitalizations among Medicare fee for service beneficiaries markedly increased interest in hospital quality improvement (QI) efforts to reduce the observed 30‐day rehospitalization of 19.6% in this elderly population.[1, 2] The Congressional Budget Office estimated that reimbursement penalties to hospitals for high readmission rates are expected to save the Medicare program approximately $7 billion between 2010 and 2019.[3] These penalties are complemented by resources from the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation aiming to reduce hospital readmissions by 20% by the end of 2013 through the Partnership for Patients campaign.[4] Although potential financial penalties and provision of resources for QI intensified efforts to enhance the quality of the hospital discharge transition, patient safety risks associated with hospital discharge are well documented.[5, 6] Approximately 20% of patients discharged from the hospital may suffer adverse events,[7, 8] of which up to three‐quarters (72%) are medication related,[9] and over one‐third of required follow‐up testing after discharge is not completed.[10] Such findings indicate opportunities for improvement in the discharge process.[11]

Numerous publications describe studies aiming to improve the hospital discharge process and mitigate these hazards, though a systematic review of interventions to reduce 30‐day rehospitalization indicated that the existing evidence base for the effectiveness of transition interventions demonstrates irregular effectiveness and limitations to generalizability.[12] Most studies showing effectiveness are confined to single academic medical centers. Existing evidence supports multifaceted interventions implemented in both the pre‐ and postdischarge periods and focused on risk assessment and tailored, patient‐centered application of interventions to mitigate risk. For example Project RED (Re‐Engineered Discharge) applied a bundled intervention consisting of intensified patient education and discharge planning, improved medication reconciliation and discharge instructions, and longitudinal patient contact with follow‐up phone calls and a dedicated discharge advocate.[13] However, the mean age of patients participating in the study was 50 years, and it excluded patients admitted from or discharged to skilled nursing facilities, making generalizability to the geriatric population uncertain.

An integral aspect of QI projects is the contribution of local context to translation of best practices to disparate settings.[14, 15, 16] Most available reports of successful interventions to reduce rehospitalization have not fully described the specifics of either the intervention context or design. Moreover, the available evidence base for common interventions to reduce rehospitalization was developed in the academic setting. Validation of single academic center studies in a broader healthcare context is necessary.

Project BOOST (Better Outcomes for Older adults through Safe Transitions) recruited a diverse national cohort of both academic and nonacademic hospitals to participate in a QI effort to implement best practices for hospital discharge care transitions using a national collaborative approach facilitated by external expert mentorship. This study aimed to determine the effectiveness of BOOST in lowering hospital readmission rates and impact on length of stay.

METHODS

The study of Project BOOST was undertaken in accordance with the SQUIRE (Standards for Quality Improvement Reporting Excellence) Guidelines.[17]

Participants

The unit of observation for the prospective cohort study was the clinical acute‐care unit within hospitals. Sites were instructed to designate a pilot unit for the intervention that cared for medical or mixed medicalsurgical patient populations. Sites were also asked to provide outcome data for a clinically and organizationally similar non‐BOOST unit to provide a site‐matched control. Control units were matched by local site leadership based on comparable patient demographics, clinical mix, and extent of housestaff presence. An initial cohort of 6 hospitals in 2008 was followed by a second cohort of 24 hospitals initiated in 2009. All hospitals were invited to participate in the national effectiveness analysis, which required submission of readmission and length of stay data for both a BOOST intervention unit and a clinically matched control unit.

Description of the Intervention

The BOOST intervention consisted of 2 major sequential processes, planning and implementation, both facilitated by external site mentorsphysicians expert in QI and care transitionsfor a period of 12 months. Extensive background on the planning and implementation components is available at

| Enrollment Sites, n=30 | Sites Reporting Outcome Data, n=11 | Sites Not Reporting Outcome Data, n=19 | P Value for Comparison of Outcome Data Sites Compared to Othersa | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Region, n (%) | 0.194 | |||

| Northeast | 8 (26.7) | 2 (18.2) | 6 (31.6) | |

| West | 7 (23.4) | 2 (18.2) | 5 (26.3) | |

| South | 7 (23.4) | 3 (27.3) | 4 (21.1) | |

| Midwest | 8 (26.7) | 4 (36.4) | 4 (21.1) | |

| Urban location, n (%) | 25 (83.3) | 11 (100) | 15 (78.9) | 0.035 |

| Teaching status, n (%) | 0.036 | |||

| Academic medical center | 10 (33.4) | 5 (45.5) | 5 (26.3) | |

| Community teaching | 8 (26.7) | 3 (27.3) | 5 (26.3) | |

| Community nonteaching | 12 (40) | 3 (27.3) | 9 (47.4) | |

| Beds number, mean (SD) | 426.6 (220.6) | 559.2 (187.8) | 349.79 (204.48) | 0.003 |

| Number of tools implemented, n (%) | 0.194 | |||

| 0 | 2 (6.7) | 0 | 2 (10.5) | |

| 1 | 2 (6.7) | 0 | 2 (10.5) | |

| 2 | 4 (13.3) | 2 (18.2) | 2 (10.5) | |

| 3 | 12 (40.0) | 3 (27.3) | 8 (42.1) | |

| 4 | 9 (30.0) | 5 (45.5) | 4 (21.1) | |

| 5 | 1 (3.3) | 1 (9.1) | 1 (5.3) | |

Mentor engagement with sites consisted of a 2‐day kickoff training on the BOOST tools, where site teams met their mentor and initiated development of structured action plans, followed by 5 to 6 scheduled phone calls in the subsequent 12 months. During these conference calls, mentors gauged progress and sought to help troubleshoot barriers to implementation. Some mentors also conducted a site visit with participant sites. Project BOOST provided sites with several collaborative activities including online webinars and an online listserv. Sites also received a quarterly newsletter.

Outcome Measures

The primary outcome was 30‐day rehospitalization defined as same hospital, all‐cause rehospitalization. Home discharges as well as discharges or transfers to other healthcare facilities were included in the discharge calculation. Elective or scheduled rehospitalizations as well as multiple rehospitalizations in the same 30‐day window were considered individual rehospitalization events. Rehospitalization was reported as a ratio of 30‐day rehospitalizations divided by live discharges in a calendar month. Length of stay was reported as the mean length of stay among live discharges in a calendar month. Outcomes were calculated at the participant site and then uploaded as overall monthly unit outcomes to a Web‐based research database.

To account for seasonal trends as well as marked variation in month‐to‐month rehospitalization rates identified in longitudinal data, we elected to compare 3‐month year‐over‐year averages to determine relative changes in readmission rates from the period prior to BOOST implementation to the period after BOOST implementation. We calculated averages for rehospitalization and length of stay in the 3‐month period preceding the sites' first reported month of front‐line implementation and in the corresponding 3‐month period in the subsequent calendar year. For example, if a site reported implementing its first tool in April 2010, the average readmission rate in the unit for January 2011 through March 2011 was subtracted from the average readmission rate for January 2010 through March 2010.

Sites were surveyed regarding tool implementation rates 6 months and 24 months after the 2009 kickoff training session. Surveys were electronically completed by site leaders in consultation with site team members. The survey identified new tool implementation as well as modification of existing care processes using the BOOST tools (admission risk assessment, discharge readiness checklist, teach back use, mandate regarding discharge summary completion, follow‐up phone calls to >80% of discharges). Use of a sixth tool, creation of individualized written discharge instructions, was not measured. We credited sites with tool implementation if they reported either de novo tool use or alteration of previous care processes influenced by BOOST tools.

Clinical outcome reporting was voluntary, and sites did not receive compensation and were not subject to penalty for the degree of implementation or outcome reporting. No patient‐level information was collected for the analysis, which was approved by the Northwestern University institutional review board.

Data Sources and Methods

Readmission and length of stay data, including the unit level readmission rate, as collected from administrative sources at each hospital, were collected using templated spreadsheet software between December 2008 and June 2010, after which data were loaded directly to a Web‐based data‐tracking platform. Sites were asked to load data as they became available. Sites were asked to report the number of study unit discharges as well as the number of those discharges readmitted within 30 days; however, reporting of the number of patient discharges was inconsistent across sites. Serial outreach consisting of monthly phone calls or email messaging to site leaders was conducted throughout 2011 to increase site participation in the project analysis.

Implementation date information was collected from 2 sources. The first was through online surveys distributed in November 2009 and April 2011. The second was through fields in the Web‐based data tracking platform to which sites uploaded data. In cases where disagreement was found between these 2 sources, the site leader was contacted for clarification.

Practice setting (community teaching, community nonteaching, academic medical center) was determined by site‐leader report within the Web‐based data tracking platform. Data for hospital characteristics (number of licensed beds and geographic region) were obtained from the American Hospital Association's Annual Survey of Hospitals.[18] Hospital region was characterized as West, South, Midwest, or Northeast.

Analysis

The null hypothesis was that no prepost difference existed in readmission rates within BOOST units, and no difference existed in the prepost change in readmission rates in BOOST units when compared to site‐matched control units. The Wilcoxon rank sum test was used to test whether observed changes described above were significantly different from 0, supporting rejection of the null hypotheses. We performed similar tests to determine the significance of observed changes in length of stay. We performed our analysis using SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Eleven hospitals provided rehospitalization and length‐of‐stay outcome data for both a BOOST and control unit for the pre‐ and postimplementation periods. Compared to the 19 sites that did not participate in the analysis, these 11 sites were significantly larger (559188 beds vs 350205 beds, P=0.003), more likely to be located in an urban area (100.0% [n=11] vs 78.9% [n=15], P=0.035), and more likely to be academic medical centers (45.5% [n=5] vs 26.3% [n=5], P=0.036) (Table 1).

The mean number of tools implemented by sites participating in the analysis was 3.50.9. All sites implemented at least 2 tools. The duration between attendance at the BOOST kickoff event and first tool implementation ranged from 3 months (first tool implemented prior to attending the kickoff) and 9 months (mean duration, 3.34.3 months) (Table 2).

| Hospital | Region | Hospital Type | No. Licensed Beds | Kickoff Implementationa | Risk Assessment | Discharge Checklist | Teach Back | Discharge Summary Completion | Follow‐up Phone Call | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||

| 1 | Midwest | Community teaching | <300 | 8 | 3 | |||||

| 2 | West | Community teaching | >600 | 0 | 4 | |||||

| 3 | Northeast | Academic medical center | >600 | 2 | 4 | |||||

| 4 | Northeast | Community nonteaching | <300 | 9 | 2 | |||||

| 5 | South | Community nonteaching | >600 | 6 | 3 | |||||

| 6 | South | Community nonteaching | >600 | 3 | 4 | |||||

| 7 | Midwest | Community teaching | 300600 | 1 | 5 | |||||

| 8 | West | Academic medical center | 300600 | 1 | 4 | |||||

| 9 | South | Academic medical center | >600 | 4 | 4 | |||||

| 10 | Midwest | Academic medical center | 300600 | 3 | 3 | |||||

| 11 | Midwest | Academic medical center | >600 | 9 | 2 | |||||

The average rate of 30‐day rehospitalization among BOOST units was 14.7% in the preimplementation period and 12.7% during the postimplementation period (P=0.010) (Figure 1). Rehospitalization rates for matched control units were 14.0% in the preintervention period and 14.1% in the postintervention period (P=0.831). The mean absolute reduction in readmission rates over the 1‐year study period in BOOST units compared to control units was 2.0%, or a relative reduction of 13.6% (P=0.054 for signed rank test comparing differences in readmission rate reduction in BOOST units compared to site‐matched control units). Length of stay in BOOST and control units decreased an average of 0.5 days and 0.3 days, respectively. There was no difference in length of stay change between BOOST units and control units (P=0.966).

DISCUSSION

As hospitals strive to reduce their readmission rates to avoid Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services penalties, Project BOOST may be a viable QI approach to achieve their goals. This initial evaluation of participation in Project BOOST by 11 hospitals of varying sizes across the United States showed an associated reduction in rehospitalization rates (absolute=2.0% and relative=13.6%, P=0.054). We did not find any significant change in length of stay among these hospitals implementing BOOST tools.

The tools provided to participating hospitals were developed from evidence found in peer‐reviewed literature established through experimental methods in well‐controlled academic settings. Further tool development was informed by recommendations of an advisory board consisting of expert representatives and advocates involved in the hospital discharge process: patients, caregivers, physicians, nurses, case managers, social workers, insurers, and regulatory and research agencies.[19] The toolkit components address multiple aspects of hospital discharge and follow‐up with the goal of improving health by optimizing the safety of care transitions. Our observation that readmission rates appeared to improve in a diverse hospital sample including nonacademic and community hospitals engaged in Project BOOST is reassuring that the benefits seen in existing research literature, developed in distinctly academic settings, can be replicated in diverse acute‐care settings.

The effect size observed in our study was modest but consistent with several studies identified in a recent review of trials measuring interventions to reduce rehospitalization, where 7 of 16 studies showing a significant improvement registered change in the 0% to 5% absolute range.[12] Impact of this project may have been tempered by the need to translate external QI content to the local setting. Additionally, in contrast to experimental studies that are limited in scope and timing and often scaled to a research budget, BOOST sites were encouraged to implement Project BOOST in the clinical setting even if no new funds were available to support the effort.[12]

The recruitment of a national sample of both academic and nonacademic hospital participants imposed several limitations on our study and analysis. We recognize that intervention units selected by hospitals may have had unmeasured unit and patient characteristics that facilitated successful change and contributed to the observed improvements. However, because external pressure to reduce readmission is present across all hospitals independent of the BOOST intervention, we felt site‐matched controls were essential to understanding effects attributable to the BOOST tools. Differences between units would be expected to be stable over the course of the study period, and comparison of outcome differences between 2 different time periods would be reasonable. Additionally, we could not collect data on readmissions to other hospitals. Theoretically, patients discharged from BOOST units might be more likely to have been rehospitalized elsewhere, but the fraction of rehospitalizations occurring at alternate facilities would also be expected to be similar on the matched control unit.

We report findings from a voluntary cohort willing and capable of designating a comparison clinical unit and contributing the requested data outcomes. Pilot sites that did not report outcomes were not analyzed, but comparison of hospital characteristics shows that participating hospitals were more likely to be large, urban, academic medical centers. Although barriers to data submission were not formally analyzed, reports from nonparticipating sites describe data submission limited by local implementation design (no geographic rollout or simultaneous rollout on all appropriate clinical units), site specific inability to generate unit level outcome statistics, and competing organizational priorities for data analyst time (electronic medical record deployment, alternative QI initiatives). The external validity of our results may be limited to organizations capable of analytics at the level of the individual clinical unit as well as those with sufficient QI resources to support reporting to a national database in the absence of a payer mandate. It is possible that additional financial support for on‐site data collection would have bolstered participation, making the example of participation rates we present potentially informative to organizations hoping to widely disseminate a QI agenda.

Nonetheless, the effectiveness demonstrated in the 11 sites that did participate is encouraging, and ongoing collaboration with subsequent BOOST cohorts has been designed to further facilitate data collection. Among the insights gained from this pilot experience, and incorporated into ongoing BOOST cohorts, is the importance of intensive mentor engagement to foster accountability among participant sites, assist with implementation troubleshooting, and offer expertise that is often particularly effective in gaining local support. We now encourage sites to have 2 mentor site visits to further these roles and more frequent conference calls. Further research to understand the marginal benefit of the mentored implementation approach is ongoing.

The limitations in data submission we experienced with the pilot cohort likely reflect resource constraints not uncommon at many hospitals. Increasing pressure placed on hospitals as a result of the Readmission Reduction Program within the Affordable Care Act as well as increasing interest from private and Medicaid payors to incorporate similar readmission‐based penalties provide encouragement for hospitals to enhance their data and analytic skills. National incentives for implementation of electronic health records (EHR) should also foster such capabilities, though we often saw EHRs as a barrier to QI, especially rapid cycle trials. Fortunately, hospitals are increasingly being afforded access to comprehensive claims databases to assist in tracking readmission rates to other facilities, and these data are becoming available in a more timely fashion. This more robust data collection, facilitated by private payors, state QI organizations, and state hospital associations, will support additional analytic methods such as multivariate regression models and interrupted time series designs to appreciate the experience of current BOOST participants.

Additional research is needed to understand the role of organizational context in the effectiveness of Project BOOST. Differences in rates of tool implementation and changes in clinical outcomes are likely dependent on local implementation context at the level of the healthcare organization and individual clinical unit.[20] Progress reports from site mentors and previously described experiences of QI implementation indicate that successful implementation of a multidimensional bundle of interventions may have reflected a higher level of institutional support, more robust team engagement in the work of reducing readmissions, increased clinical staff support for change, the presence of an effective project champion, or a key facilitating role of external mentorship.[21, 22] Ongoing data collection will continue to measure the sustainability of tool use and observed outcome changes to inform strategies to maintain gains associated with implementation. The role of mentored implementation in facilitating gains also requires further study.

Increasing attention to the problem of avoidable rehospitalization is driving hospitals, insurers, and policy makers to pursue QI efforts that favorably impact readmission rates. Our analysis of the BOOST intervention suggests that modest gains can be achieved following evidence‐based hospital process change facilitated by a mentored implementation model. However, realization of the goal of a 20% reduction in rehospitalization proposed by the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services' Partnership for Patients initiative may be difficult to achieve on a national scale,[23] especially if efforts focus on just the hospital.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the contributions of Amanda Creden, BA (data collection), Julia Lee (biostatistical support), and the support of Amy Berman, BS, RN, Senior Program Officer at The John A. Hartford Foundation.

Disclosures

Project BOOST was funded by a grant from The John A. Hartford Foundation. Project BOOST is administered by the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM). The development of the Project BOOST toolkit, recruitment of sites for this study, mentorship of the pilot cohort, project evaluation planning, and collection of pilot data were funded by a grant from The John A. Harford Foundation. Additional funding for continued data collection and analysis was funded by the SHM through funds from hospitals to participate in Project BOOST, specifically with funding support for Dr. Hansen. Dr. Williams has received funding to serve as Principal Investigator for Project BOOST. Since the time of initial cohort participation, approximately 125 additional hospitals have participated in the mentored implementation of Project BOOST. This participation was funded through a combination of site‐based tuition, third‐party payor support from private insurers, foundations, and federal funding through the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation Partnership for Patients program. Drs. Greenwald, Hansen, and Williams are Project BOOST mentors for current Project BOOST sites and receive financial support through the SHM for this work. Dr. Howell has previously received funding as a Project BOOST mentor. Ms. Budnitz is the BOOST Project Director and is Chief Strategy and Development Officer for the HM. Dr. Maynard is the Senior Vice President of the SHM's Center for Hospital Innovation and Improvement.

References

- , , . Rehospitalizations among patients in the Medicare fee‐for‐service program. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(14):1418–1428.

- United States Congress. House Committee on Education and Labor. Coe on Ways and Means, Committee on Energy and Commerce, Compilation of Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act: as amended through November 1, 2010 including Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act health‐related portions of the Health Care and Education Reconciliation Act of 2010. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office; 2010.

- Cost estimate for the amendment in the nature of a substitute to H.R. 3590, as proposed in the Senate on November 18, 2009. Washington, DC: Congressional Budget Office; 2009.

- Partnership for Patients, Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation. Available at: http://www.innovations.cms.gov/initiatives/Partnership‐for‐Patients/index.html. Accessed December 12, 2012.

- , . Providers have failed to work for continuity. Hospitals. 1979;53(10):79.

- , . Executing high‐quality care transitions: a call to do it right. J Hosp Med. 2007;2(5):287–290.

- , , , , . The incidence and severity of adverse events affecting patients after discharge from the hospital. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138(3):161–167.

- , , , et al. Adverse events among medical patients after discharge from hospital. CMAJ. 2004;170(3):345–349.

- , , , et al. Making inpatient medication reconciliation patient centered, clinically relevant and implementable: a consensus statement on key principles and necessary first steps. J Hosp Med. 2010;5(8):477–485.

- , , . Tying up loose ends: discharging patients with unresolved medical issues. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(12):1305.

- , , , , , . Deficits in communication and information transfer between hospital‐based and primary care physicians. JAMA. 2007;297(8):831–841.

- , , , , . Interventions to reduce 30‐day rehospitalization: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(8):520–528.

- , , , et al. A reengineered hospital discharge program to decrease rehospitalization: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150(3):178.

- , , , et al. Advancing the science of patient safety. Ann Intern Med. 2011;154(10):693–696.

- , . From best evidence to best practice: effective implementation of change in patients' care. Lancet. 2003;362(9391):1225–1230.

- , , , et al. Quality improvement projects targeting health care‐associated infections: comparing virtual collaborative and toolkit approaches. J Hosp Med. 2011;6(5):271–278.

- , , , , . Publication guidelines for improvement studies in health care: evolution of the SQUIRE project. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149(9):670–676.

- , , , . Risk stratification and therapeutic decision making in acute coronary syndromes. JAMA. 2000;284(7):876–878.

- , , . Are diagnosis specific outcome indicators based on administrative data useful in assessing quality of hospital care? BMJ. 2004;13(1):32.

- , , , et al. What distinguishes top‐performing hospitals in acute myocardial infarction mortality rates? Ann Intern Med. 2011;154(6):384–390.

- , , , . The Model for Understanding Success in Quality (MUSIQ): building a theory of context in healthcare quality improvement. BMJ Qual Saf. 2012;21(1):13–20.

- , . Evidence‐based quality improvement: the state of the science. Health Aff (Millwood). 2005;24(1):138–150.

- Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation. Partnership for patients. Available at: http://www.innovations.cms.gov/initiatives/Partnership‐for‐Patients/index.html. Accessed April 2, 2012.

- , , . Rehospitalizations among patients in the Medicare fee‐for‐service program. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(14):1418–1428.