User login

Editorial

One year of the Journal of Hospital Medicine is done, and we now embark on our second with this first issue of volume 2. Before moving on, I heartily thank all the authors who contributed their manuscripts to the Journal of Hospital Medicine (JHM), bravely investing in this new academic periodical. A remarkable 284 manuscripts have been submitted since we first opened the JHM Web site, 197 of them during 2006. This clearly reflects the robust demand by hospitalists and their colleagues for original research and relevant clinical reviews about our evolving specialty of hospital medicine. I probably should not be surprised that this demand exists among the 15,000‐plus hospitalists in America and the 6000‐plus members of the Society of Hospital Medicine. Regardless, I am ineffably humbled by the enthusiasm and energy of all the contributors.

Understandably, this volume of submissions, exceeding our projections by nearly 50%, required yeoman's work by our associate editors and reviewers. On page 55 we list the 203 reviewers who donated their time and acumen to assure the quality of our publication. Many reviewed more than 4 articles during the year. Our associate editors deserve particular appreciation and gratitude for their willingness to donate extraordinary amounts of time and effort to ensure the success of JHMVincent Chang from Boston Children's Hospital, Scott Flanders from the University of Michigan, Karen Hauer from the University of California, San Francisco, Jean Kutner from the University of Colorado, James Pile from Cleveland MetroHealth, and Kaveh Shojania from the University of Ottawa. Additionally, the energetic assistant editors have supported them and me with frequent reviews, article submissions, and creative ideas for improving the journal. Finally, our auspicious editorial board has proffered sage guidance, and many of its members have also submitted manuscripts and participated in reviewing articles.

Moving forward we expect continued growth, as both the submitted articles and demand for the journal are being recognized. At 7:29 a.m. on November 30, 2006, Vickie Thaw (Vice President and Publisher, John Wiley & Sons, Inc.) called me to report that the National Library of Medicine validated all our efforts. The Journal of Hospital Medicine had been selected for indexing and inclusion in the National Library of Medicine's MEDLINE (Medical Literature Analysis and Retrieval System Online). The primary component of PubMed, MEDLINE is a bibliographic database containing approximately 13 million references to journal articles on medicine, nursing, dentistry, veterinary medicine, health care systems, and preclinical sciences dating to the mid‐1960s. With this approval, hospital medicine has achieved another milestone in its evolution into a new specialty.

We now hope to respond to the robust interest in clinical materials as well as to continue publication of original research. To achieve our aim of increasing the amount of clinically relevant content for practicing hospitalists, authors are encouraged to submit to JHM case reports, clinical updates, and clinical images that convey novel or underappreciated teaching points. Teaching points may be purely clinical and may focus on clinical pearls or unusual presentations of well‐known diseases, although submission of straightforward presentations of rare diseases is discouraged. Alternatively, manuscripts may involve succinct case‐based descriptions of innovations, quality improvementrelated issues, or medical errors. Submitted case reports should be less than 800 words and should contain a maximum of 5 references and no more than 1 table or figure. Case reports should not include an abstract. Submission of the case report and review type should be avoided. Instead, we seek formal clinical updates of no more than 2000 words that present important aspects of a case along with new research findings and citations from the literature that change what has historically been the standard of delivery of care. Finally, we continue to seek cases most appropriate for the Hospital Images Dx section, edited by Paul Aronowitz. They should be submitted with that designation and have fewer than 150 words. These 3 categories are identified on our Manuscript Central website (

Again, thanks to all of you for making the launch of the Journal of Hospital Medicine an unqualified success. We look forward to your continued participation as we grow as the premier journal for the specialty of hospital medicine.

P.S. Sadly, one of our superstar associate editors, Kaveh Shojania, is stepping aside, and we sincerely express thanks for his terrific contributions. We welcome suggestions for an alternative to fulfill his responsibilities.

One year of the Journal of Hospital Medicine is done, and we now embark on our second with this first issue of volume 2. Before moving on, I heartily thank all the authors who contributed their manuscripts to the Journal of Hospital Medicine (JHM), bravely investing in this new academic periodical. A remarkable 284 manuscripts have been submitted since we first opened the JHM Web site, 197 of them during 2006. This clearly reflects the robust demand by hospitalists and their colleagues for original research and relevant clinical reviews about our evolving specialty of hospital medicine. I probably should not be surprised that this demand exists among the 15,000‐plus hospitalists in America and the 6000‐plus members of the Society of Hospital Medicine. Regardless, I am ineffably humbled by the enthusiasm and energy of all the contributors.

Understandably, this volume of submissions, exceeding our projections by nearly 50%, required yeoman's work by our associate editors and reviewers. On page 55 we list the 203 reviewers who donated their time and acumen to assure the quality of our publication. Many reviewed more than 4 articles during the year. Our associate editors deserve particular appreciation and gratitude for their willingness to donate extraordinary amounts of time and effort to ensure the success of JHMVincent Chang from Boston Children's Hospital, Scott Flanders from the University of Michigan, Karen Hauer from the University of California, San Francisco, Jean Kutner from the University of Colorado, James Pile from Cleveland MetroHealth, and Kaveh Shojania from the University of Ottawa. Additionally, the energetic assistant editors have supported them and me with frequent reviews, article submissions, and creative ideas for improving the journal. Finally, our auspicious editorial board has proffered sage guidance, and many of its members have also submitted manuscripts and participated in reviewing articles.

Moving forward we expect continued growth, as both the submitted articles and demand for the journal are being recognized. At 7:29 a.m. on November 30, 2006, Vickie Thaw (Vice President and Publisher, John Wiley & Sons, Inc.) called me to report that the National Library of Medicine validated all our efforts. The Journal of Hospital Medicine had been selected for indexing and inclusion in the National Library of Medicine's MEDLINE (Medical Literature Analysis and Retrieval System Online). The primary component of PubMed, MEDLINE is a bibliographic database containing approximately 13 million references to journal articles on medicine, nursing, dentistry, veterinary medicine, health care systems, and preclinical sciences dating to the mid‐1960s. With this approval, hospital medicine has achieved another milestone in its evolution into a new specialty.

We now hope to respond to the robust interest in clinical materials as well as to continue publication of original research. To achieve our aim of increasing the amount of clinically relevant content for practicing hospitalists, authors are encouraged to submit to JHM case reports, clinical updates, and clinical images that convey novel or underappreciated teaching points. Teaching points may be purely clinical and may focus on clinical pearls or unusual presentations of well‐known diseases, although submission of straightforward presentations of rare diseases is discouraged. Alternatively, manuscripts may involve succinct case‐based descriptions of innovations, quality improvementrelated issues, or medical errors. Submitted case reports should be less than 800 words and should contain a maximum of 5 references and no more than 1 table or figure. Case reports should not include an abstract. Submission of the case report and review type should be avoided. Instead, we seek formal clinical updates of no more than 2000 words that present important aspects of a case along with new research findings and citations from the literature that change what has historically been the standard of delivery of care. Finally, we continue to seek cases most appropriate for the Hospital Images Dx section, edited by Paul Aronowitz. They should be submitted with that designation and have fewer than 150 words. These 3 categories are identified on our Manuscript Central website (

Again, thanks to all of you for making the launch of the Journal of Hospital Medicine an unqualified success. We look forward to your continued participation as we grow as the premier journal for the specialty of hospital medicine.

P.S. Sadly, one of our superstar associate editors, Kaveh Shojania, is stepping aside, and we sincerely express thanks for his terrific contributions. We welcome suggestions for an alternative to fulfill his responsibilities.

One year of the Journal of Hospital Medicine is done, and we now embark on our second with this first issue of volume 2. Before moving on, I heartily thank all the authors who contributed their manuscripts to the Journal of Hospital Medicine (JHM), bravely investing in this new academic periodical. A remarkable 284 manuscripts have been submitted since we first opened the JHM Web site, 197 of them during 2006. This clearly reflects the robust demand by hospitalists and their colleagues for original research and relevant clinical reviews about our evolving specialty of hospital medicine. I probably should not be surprised that this demand exists among the 15,000‐plus hospitalists in America and the 6000‐plus members of the Society of Hospital Medicine. Regardless, I am ineffably humbled by the enthusiasm and energy of all the contributors.

Understandably, this volume of submissions, exceeding our projections by nearly 50%, required yeoman's work by our associate editors and reviewers. On page 55 we list the 203 reviewers who donated their time and acumen to assure the quality of our publication. Many reviewed more than 4 articles during the year. Our associate editors deserve particular appreciation and gratitude for their willingness to donate extraordinary amounts of time and effort to ensure the success of JHMVincent Chang from Boston Children's Hospital, Scott Flanders from the University of Michigan, Karen Hauer from the University of California, San Francisco, Jean Kutner from the University of Colorado, James Pile from Cleveland MetroHealth, and Kaveh Shojania from the University of Ottawa. Additionally, the energetic assistant editors have supported them and me with frequent reviews, article submissions, and creative ideas for improving the journal. Finally, our auspicious editorial board has proffered sage guidance, and many of its members have also submitted manuscripts and participated in reviewing articles.

Moving forward we expect continued growth, as both the submitted articles and demand for the journal are being recognized. At 7:29 a.m. on November 30, 2006, Vickie Thaw (Vice President and Publisher, John Wiley & Sons, Inc.) called me to report that the National Library of Medicine validated all our efforts. The Journal of Hospital Medicine had been selected for indexing and inclusion in the National Library of Medicine's MEDLINE (Medical Literature Analysis and Retrieval System Online). The primary component of PubMed, MEDLINE is a bibliographic database containing approximately 13 million references to journal articles on medicine, nursing, dentistry, veterinary medicine, health care systems, and preclinical sciences dating to the mid‐1960s. With this approval, hospital medicine has achieved another milestone in its evolution into a new specialty.

We now hope to respond to the robust interest in clinical materials as well as to continue publication of original research. To achieve our aim of increasing the amount of clinically relevant content for practicing hospitalists, authors are encouraged to submit to JHM case reports, clinical updates, and clinical images that convey novel or underappreciated teaching points. Teaching points may be purely clinical and may focus on clinical pearls or unusual presentations of well‐known diseases, although submission of straightforward presentations of rare diseases is discouraged. Alternatively, manuscripts may involve succinct case‐based descriptions of innovations, quality improvementrelated issues, or medical errors. Submitted case reports should be less than 800 words and should contain a maximum of 5 references and no more than 1 table or figure. Case reports should not include an abstract. Submission of the case report and review type should be avoided. Instead, we seek formal clinical updates of no more than 2000 words that present important aspects of a case along with new research findings and citations from the literature that change what has historically been the standard of delivery of care. Finally, we continue to seek cases most appropriate for the Hospital Images Dx section, edited by Paul Aronowitz. They should be submitted with that designation and have fewer than 150 words. These 3 categories are identified on our Manuscript Central website (

Again, thanks to all of you for making the launch of the Journal of Hospital Medicine an unqualified success. We look forward to your continued participation as we grow as the premier journal for the specialty of hospital medicine.

P.S. Sadly, one of our superstar associate editors, Kaveh Shojania, is stepping aside, and we sincerely express thanks for his terrific contributions. We welcome suggestions for an alternative to fulfill his responsibilities.

Editorial

People willingly believe what they wish.

Chinese fortune cookie

Being a hospitalist provides us with many rewards in life: a secure job, decent income, intellectually stimulating experiences at work, and gratification from helping the patients we encounter. Importantly, without patients none of this would be possible. Their role in our work lives and their personal experience in the hospital vary dramatically from ours, and that experience may be relatively invisible to many of us. Be honesthave you fully recognized the apprehension and even terror experienced by some patients when nightfall sweeps through the hospital wards and the commotion and attention of the day shift dissipates?1 Have you been fully aware of the desperate need of patients or their family members for timely communication of understandable information in the midst of critical illness?2 We willingly believe what we wishpatients and their families are having a comforting experience while hospitalized, and we are doing wonderful jobs as hospitalists caring for them. However, the lay press indicates that the patient's perception may differ radically from this reassuring point of view.3

To comprehend fully the hospital experience of patients and their families, we can benefit from them telling us their stories. The narrative stories from a patient1 and the wife of a patient2 clearly convey the apprehension and fear both patients and their loved ones suffer. Without this appreciation, we cannot empathetically deliver the care patients deserve. Not surprisingly, as medical technology guides physicians to focus more on the disease instead of the person, a backlash of an increasing emphasis on patient‐centered care is emerging.4, 5 Through short essays on illuminating experiences of physicians, patients, or families of patients, I hope to bring the patient's perspective to the forefront of hospital medicine care. View from the Hospital Bed can educate us about patients' perspectives on the experience of being hospitalized. We can also learn from the families of patients in View from the Hospital Room. The next time you recognize that a patient or family member has a potent story to tell (good or bad), encourage them to send it to us at the Journal of Hospital Medicine.

For the secret of the care of the patient is in caring for the patient.

Francis W. Peabody, MD

October 21, 1925

- .Uncharted waters.J Hosp Med.2006;1:136–137.

- .Hospitals foreign soil for those who don't work there.J Hosp Med.1006;1:70–72.

- .In the hospital, a degrading shift from person to patient.New York Times. Aug. 16,2005.

- .Towards a global definition of patient centred care.Br Med J.2001;322:444–445.

- ,.Engaging patients in medical decision making.Br Med J.2001;323:584–585.

People willingly believe what they wish.

Chinese fortune cookie

Being a hospitalist provides us with many rewards in life: a secure job, decent income, intellectually stimulating experiences at work, and gratification from helping the patients we encounter. Importantly, without patients none of this would be possible. Their role in our work lives and their personal experience in the hospital vary dramatically from ours, and that experience may be relatively invisible to many of us. Be honesthave you fully recognized the apprehension and even terror experienced by some patients when nightfall sweeps through the hospital wards and the commotion and attention of the day shift dissipates?1 Have you been fully aware of the desperate need of patients or their family members for timely communication of understandable information in the midst of critical illness?2 We willingly believe what we wishpatients and their families are having a comforting experience while hospitalized, and we are doing wonderful jobs as hospitalists caring for them. However, the lay press indicates that the patient's perception may differ radically from this reassuring point of view.3

To comprehend fully the hospital experience of patients and their families, we can benefit from them telling us their stories. The narrative stories from a patient1 and the wife of a patient2 clearly convey the apprehension and fear both patients and their loved ones suffer. Without this appreciation, we cannot empathetically deliver the care patients deserve. Not surprisingly, as medical technology guides physicians to focus more on the disease instead of the person, a backlash of an increasing emphasis on patient‐centered care is emerging.4, 5 Through short essays on illuminating experiences of physicians, patients, or families of patients, I hope to bring the patient's perspective to the forefront of hospital medicine care. View from the Hospital Bed can educate us about patients' perspectives on the experience of being hospitalized. We can also learn from the families of patients in View from the Hospital Room. The next time you recognize that a patient or family member has a potent story to tell (good or bad), encourage them to send it to us at the Journal of Hospital Medicine.

For the secret of the care of the patient is in caring for the patient.

Francis W. Peabody, MD

October 21, 1925

People willingly believe what they wish.

Chinese fortune cookie

Being a hospitalist provides us with many rewards in life: a secure job, decent income, intellectually stimulating experiences at work, and gratification from helping the patients we encounter. Importantly, without patients none of this would be possible. Their role in our work lives and their personal experience in the hospital vary dramatically from ours, and that experience may be relatively invisible to many of us. Be honesthave you fully recognized the apprehension and even terror experienced by some patients when nightfall sweeps through the hospital wards and the commotion and attention of the day shift dissipates?1 Have you been fully aware of the desperate need of patients or their family members for timely communication of understandable information in the midst of critical illness?2 We willingly believe what we wishpatients and their families are having a comforting experience while hospitalized, and we are doing wonderful jobs as hospitalists caring for them. However, the lay press indicates that the patient's perception may differ radically from this reassuring point of view.3

To comprehend fully the hospital experience of patients and their families, we can benefit from them telling us their stories. The narrative stories from a patient1 and the wife of a patient2 clearly convey the apprehension and fear both patients and their loved ones suffer. Without this appreciation, we cannot empathetically deliver the care patients deserve. Not surprisingly, as medical technology guides physicians to focus more on the disease instead of the person, a backlash of an increasing emphasis on patient‐centered care is emerging.4, 5 Through short essays on illuminating experiences of physicians, patients, or families of patients, I hope to bring the patient's perspective to the forefront of hospital medicine care. View from the Hospital Bed can educate us about patients' perspectives on the experience of being hospitalized. We can also learn from the families of patients in View from the Hospital Room. The next time you recognize that a patient or family member has a potent story to tell (good or bad), encourage them to send it to us at the Journal of Hospital Medicine.

For the secret of the care of the patient is in caring for the patient.

Francis W. Peabody, MD

October 21, 1925

- .Uncharted waters.J Hosp Med.2006;1:136–137.

- .Hospitals foreign soil for those who don't work there.J Hosp Med.1006;1:70–72.

- .In the hospital, a degrading shift from person to patient.New York Times. Aug. 16,2005.

- .Towards a global definition of patient centred care.Br Med J.2001;322:444–445.

- ,.Engaging patients in medical decision making.Br Med J.2001;323:584–585.

- .Uncharted waters.J Hosp Med.2006;1:136–137.

- .Hospitals foreign soil for those who don't work there.J Hosp Med.1006;1:70–72.

- .In the hospital, a degrading shift from person to patient.New York Times. Aug. 16,2005.

- .Towards a global definition of patient centred care.Br Med J.2001;322:444–445.

- ,.Engaging patients in medical decision making.Br Med J.2001;323:584–585.

Editorial

You hold in your hands the inaugural issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine (JHM). Our goal is for JHM to become the premier forum for peer‐reviewed research articles and evidence‐based reviews in the specialty of hospital medicine.

Yes, the specialty of hospital medicine. This official publication of the Society of Hospital Medicine signifies another step forward in the evolution of this specialty. With the publication of JHM the Society of Hospital Medicine continues its pivotal educational and leadership role in shaping the practice of hospital medicine. The Society is dedicated to promoting the highest‐quality care for all hospitalized patients and excellence in hospital medicine through education, advocacy, and research. As part of the Society's effort to improve care and standards, it is providing JHM to all members as part of their membership. We hope that our readership will grow to include individuals involved in all aspects of hospital care.

Packed with the results of new studies and state‐of‐the‐art reviews, JHM is not aimed solely at academicians and voracious readers of the medical literature. Rather, we hope that it fills a practical need to promote lifelong learning in both hospitalists and their hospital colleagues. For example, in this issue, national experts in palliative care and geriatrics summarize the pertinent literature and the important role of such care for hospitalized patients. JHM will also serve as a key venue for hospital medicine researchers to disseminate their findings and for educators to share their knowledge and techniques.

Why bother to create yet another journal? Given the stacks of journals that adorn many of our desks (and some of our chairs and windowsills), do we really need another to get lost among the mail that inundates us? We believe the field of hospital medicine involves a growing body of knowledge deserving of a journal focused solely on it. Hospital medicine evolved from efforts to fill a need identified by overstretched primary care physicians in the late 1980s. Physicians like the cofounders of SHM, John Nelson in Florida and Win Whitcomb in Massachusetts, began careers in a field that today numbers more than 12,000 physicians. Labeled with the moniker hospitalist given us by Bob Wachter and Lee Goldman,1 we now make up the fastest‐growing medical specialty in the United States.2 Yet, until now, no journal was devoted solely to this specialty.

The Journal of Hospital Medicine aims to provide physicians and other health care professionals with continuing insight into the basic and clinical sciences to support informed clinical decision making in the hospital. As hospitalists increasingly take an active role in the successful delivery of bench research discoveries to the bedside and become vigorous participants in the translational and clinical research sought by the National Institutes of Health,3 JHM will disseminate their findings. In addition, we hope to foster balanced debates on medical issues and health care trends that affect hospital medicine and patient care. Nonclinical aspects of hospital medicine also will be featured, including public health and the political, philosophic, ethical, legal, environmental, economic, historical, and cultural issues surrounding hospital care. We especially want to encourage submissions that evaluate projects involving the entire hospital care team: physicians and our colleagues in the hospitalnurses, pharmacists, administrators, physical and occupational therapists, social workers, and case managers.

Two articles (see pages 48 and 57) highlight this inaugural issue. One describes the development of The Core Competencies in Hospital Medicine: A Framework for Curriculum Development (a supplement to this issue), and the other demonstrates how this document can be applied to curriculum development.4, 5 This milestone in the evolution of hospital medicine provides an initial structural framework to guide medical educators in developing curricula that incorporate these competencies into the training and evaluation of students, clinicians‐in‐training, and practicing hospitalists.4 The president and CEO of the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM), Christine Cassel, offers her perspective on this landmark document.6 Its timeliness is reflected by the current efforts of the American College of Physicians, the ABIM, and others to redesign the training and the certification requirements of internists. As this supplement demonstrates, the Society of Hospital Medicine will be intimately involved in this process.

After this auspicious start, subsequent issues will include articles in the following categories. Original research articles will report results of randomized controlled trials, evaluations of diagnostic tests, prospective cohort studies, casecontrol studies, and high‐quality observational studies. We are interested in publishing both quantitative and qualitative research. Review articles, especially those targeting the hospital medicine core competencies, are eagerly sought. We also seek descriptions of interventions that transform hospital care delivery in the hospital. For example, accounts of the implementation of quality‐improvement projects and outcomes, including barriers that were overcome or that blocked implementation, would be invaluable to hospitalists throughout the country. Clinical conundrums should describe clinical cases that present diagnostic dilemmas or involve issues of medical errors. To facilitate the professional development of hospitalists, we seek articles focused on their professional development in community, academic, and administrative settings. Examples of leadership topics are managing physician performance, leading and managing change, and self‐evaluation. Teaching tips or descriptions of educational programs or curricula also are desired. For researchers, potential topics include descriptions of specific techniques used for surveys, meta‐analyses, economic evaluations, and statistical analyses.Penetrating point manuscripts, those that go beyond the cutting edge to explain the next potential breakthrough or intervention in the developing field of hospital medicine, may be authored by thought leaders inside and outside the health care field as well as by hospitalists with novel ideas. Equally vital, I want to share the illuminating perspectives of physicians, patients, and families of patients as they reflect on the experience of being in the hospitalhospitalists can enlighten us through their handoffs, and patients and their families can inform us about their view from the hospital bed.

Finally, never forget that this is your journal. Let me know what you like and what changes you think can make it better. Please e‐mail your suggestions, comments, criticisms, and ideas to us at JHMeditor@ hospitalmedicine.org. This is your chance to help shape the practice of hospital medicine and the future of hospital care. I look forward to your guidance. Together we can expand our knowledge and continue to grow in our careers.

The more you see the less you know

The less you find out as you grow

I knew much more then than I do now.

U2, City of Blinding Lights,

How to Dismantle an Atomic Bomb

- ,.The emerging role of “hospitalists” in the American health care system.N Engl J Med.1996;335:514–517.

- .The future of hospital medicine: evolution or revolution?Am J Med.2004;117:446–450.

- .Translational and clinical science—time for a new vision.N Engl J Med2005;35:1621‐1623.

- ,,,,, eds.The core competencies in hospital medicine: development and methodology.J Hosp Med.2006;1:48–56.

- ,,,,.How to use The Core Competencies in Hospital Medicine: A Framework for Curriculum Development.J Hosp Med.2006;1:57–67.

- .Hospital medicine: early successes and challenges ahead.J Hosp Med.2006;1:3–4.

You hold in your hands the inaugural issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine (JHM). Our goal is for JHM to become the premier forum for peer‐reviewed research articles and evidence‐based reviews in the specialty of hospital medicine.

Yes, the specialty of hospital medicine. This official publication of the Society of Hospital Medicine signifies another step forward in the evolution of this specialty. With the publication of JHM the Society of Hospital Medicine continues its pivotal educational and leadership role in shaping the practice of hospital medicine. The Society is dedicated to promoting the highest‐quality care for all hospitalized patients and excellence in hospital medicine through education, advocacy, and research. As part of the Society's effort to improve care and standards, it is providing JHM to all members as part of their membership. We hope that our readership will grow to include individuals involved in all aspects of hospital care.

Packed with the results of new studies and state‐of‐the‐art reviews, JHM is not aimed solely at academicians and voracious readers of the medical literature. Rather, we hope that it fills a practical need to promote lifelong learning in both hospitalists and their hospital colleagues. For example, in this issue, national experts in palliative care and geriatrics summarize the pertinent literature and the important role of such care for hospitalized patients. JHM will also serve as a key venue for hospital medicine researchers to disseminate their findings and for educators to share their knowledge and techniques.

Why bother to create yet another journal? Given the stacks of journals that adorn many of our desks (and some of our chairs and windowsills), do we really need another to get lost among the mail that inundates us? We believe the field of hospital medicine involves a growing body of knowledge deserving of a journal focused solely on it. Hospital medicine evolved from efforts to fill a need identified by overstretched primary care physicians in the late 1980s. Physicians like the cofounders of SHM, John Nelson in Florida and Win Whitcomb in Massachusetts, began careers in a field that today numbers more than 12,000 physicians. Labeled with the moniker hospitalist given us by Bob Wachter and Lee Goldman,1 we now make up the fastest‐growing medical specialty in the United States.2 Yet, until now, no journal was devoted solely to this specialty.

The Journal of Hospital Medicine aims to provide physicians and other health care professionals with continuing insight into the basic and clinical sciences to support informed clinical decision making in the hospital. As hospitalists increasingly take an active role in the successful delivery of bench research discoveries to the bedside and become vigorous participants in the translational and clinical research sought by the National Institutes of Health,3 JHM will disseminate their findings. In addition, we hope to foster balanced debates on medical issues and health care trends that affect hospital medicine and patient care. Nonclinical aspects of hospital medicine also will be featured, including public health and the political, philosophic, ethical, legal, environmental, economic, historical, and cultural issues surrounding hospital care. We especially want to encourage submissions that evaluate projects involving the entire hospital care team: physicians and our colleagues in the hospitalnurses, pharmacists, administrators, physical and occupational therapists, social workers, and case managers.

Two articles (see pages 48 and 57) highlight this inaugural issue. One describes the development of The Core Competencies in Hospital Medicine: A Framework for Curriculum Development (a supplement to this issue), and the other demonstrates how this document can be applied to curriculum development.4, 5 This milestone in the evolution of hospital medicine provides an initial structural framework to guide medical educators in developing curricula that incorporate these competencies into the training and evaluation of students, clinicians‐in‐training, and practicing hospitalists.4 The president and CEO of the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM), Christine Cassel, offers her perspective on this landmark document.6 Its timeliness is reflected by the current efforts of the American College of Physicians, the ABIM, and others to redesign the training and the certification requirements of internists. As this supplement demonstrates, the Society of Hospital Medicine will be intimately involved in this process.

After this auspicious start, subsequent issues will include articles in the following categories. Original research articles will report results of randomized controlled trials, evaluations of diagnostic tests, prospective cohort studies, casecontrol studies, and high‐quality observational studies. We are interested in publishing both quantitative and qualitative research. Review articles, especially those targeting the hospital medicine core competencies, are eagerly sought. We also seek descriptions of interventions that transform hospital care delivery in the hospital. For example, accounts of the implementation of quality‐improvement projects and outcomes, including barriers that were overcome or that blocked implementation, would be invaluable to hospitalists throughout the country. Clinical conundrums should describe clinical cases that present diagnostic dilemmas or involve issues of medical errors. To facilitate the professional development of hospitalists, we seek articles focused on their professional development in community, academic, and administrative settings. Examples of leadership topics are managing physician performance, leading and managing change, and self‐evaluation. Teaching tips or descriptions of educational programs or curricula also are desired. For researchers, potential topics include descriptions of specific techniques used for surveys, meta‐analyses, economic evaluations, and statistical analyses.Penetrating point manuscripts, those that go beyond the cutting edge to explain the next potential breakthrough or intervention in the developing field of hospital medicine, may be authored by thought leaders inside and outside the health care field as well as by hospitalists with novel ideas. Equally vital, I want to share the illuminating perspectives of physicians, patients, and families of patients as they reflect on the experience of being in the hospitalhospitalists can enlighten us through their handoffs, and patients and their families can inform us about their view from the hospital bed.

Finally, never forget that this is your journal. Let me know what you like and what changes you think can make it better. Please e‐mail your suggestions, comments, criticisms, and ideas to us at JHMeditor@ hospitalmedicine.org. This is your chance to help shape the practice of hospital medicine and the future of hospital care. I look forward to your guidance. Together we can expand our knowledge and continue to grow in our careers.

The more you see the less you know

The less you find out as you grow

I knew much more then than I do now.

U2, City of Blinding Lights,

How to Dismantle an Atomic Bomb

You hold in your hands the inaugural issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine (JHM). Our goal is for JHM to become the premier forum for peer‐reviewed research articles and evidence‐based reviews in the specialty of hospital medicine.

Yes, the specialty of hospital medicine. This official publication of the Society of Hospital Medicine signifies another step forward in the evolution of this specialty. With the publication of JHM the Society of Hospital Medicine continues its pivotal educational and leadership role in shaping the practice of hospital medicine. The Society is dedicated to promoting the highest‐quality care for all hospitalized patients and excellence in hospital medicine through education, advocacy, and research. As part of the Society's effort to improve care and standards, it is providing JHM to all members as part of their membership. We hope that our readership will grow to include individuals involved in all aspects of hospital care.

Packed with the results of new studies and state‐of‐the‐art reviews, JHM is not aimed solely at academicians and voracious readers of the medical literature. Rather, we hope that it fills a practical need to promote lifelong learning in both hospitalists and their hospital colleagues. For example, in this issue, national experts in palliative care and geriatrics summarize the pertinent literature and the important role of such care for hospitalized patients. JHM will also serve as a key venue for hospital medicine researchers to disseminate their findings and for educators to share their knowledge and techniques.

Why bother to create yet another journal? Given the stacks of journals that adorn many of our desks (and some of our chairs and windowsills), do we really need another to get lost among the mail that inundates us? We believe the field of hospital medicine involves a growing body of knowledge deserving of a journal focused solely on it. Hospital medicine evolved from efforts to fill a need identified by overstretched primary care physicians in the late 1980s. Physicians like the cofounders of SHM, John Nelson in Florida and Win Whitcomb in Massachusetts, began careers in a field that today numbers more than 12,000 physicians. Labeled with the moniker hospitalist given us by Bob Wachter and Lee Goldman,1 we now make up the fastest‐growing medical specialty in the United States.2 Yet, until now, no journal was devoted solely to this specialty.

The Journal of Hospital Medicine aims to provide physicians and other health care professionals with continuing insight into the basic and clinical sciences to support informed clinical decision making in the hospital. As hospitalists increasingly take an active role in the successful delivery of bench research discoveries to the bedside and become vigorous participants in the translational and clinical research sought by the National Institutes of Health,3 JHM will disseminate their findings. In addition, we hope to foster balanced debates on medical issues and health care trends that affect hospital medicine and patient care. Nonclinical aspects of hospital medicine also will be featured, including public health and the political, philosophic, ethical, legal, environmental, economic, historical, and cultural issues surrounding hospital care. We especially want to encourage submissions that evaluate projects involving the entire hospital care team: physicians and our colleagues in the hospitalnurses, pharmacists, administrators, physical and occupational therapists, social workers, and case managers.

Two articles (see pages 48 and 57) highlight this inaugural issue. One describes the development of The Core Competencies in Hospital Medicine: A Framework for Curriculum Development (a supplement to this issue), and the other demonstrates how this document can be applied to curriculum development.4, 5 This milestone in the evolution of hospital medicine provides an initial structural framework to guide medical educators in developing curricula that incorporate these competencies into the training and evaluation of students, clinicians‐in‐training, and practicing hospitalists.4 The president and CEO of the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM), Christine Cassel, offers her perspective on this landmark document.6 Its timeliness is reflected by the current efforts of the American College of Physicians, the ABIM, and others to redesign the training and the certification requirements of internists. As this supplement demonstrates, the Society of Hospital Medicine will be intimately involved in this process.

After this auspicious start, subsequent issues will include articles in the following categories. Original research articles will report results of randomized controlled trials, evaluations of diagnostic tests, prospective cohort studies, casecontrol studies, and high‐quality observational studies. We are interested in publishing both quantitative and qualitative research. Review articles, especially those targeting the hospital medicine core competencies, are eagerly sought. We also seek descriptions of interventions that transform hospital care delivery in the hospital. For example, accounts of the implementation of quality‐improvement projects and outcomes, including barriers that were overcome or that blocked implementation, would be invaluable to hospitalists throughout the country. Clinical conundrums should describe clinical cases that present diagnostic dilemmas or involve issues of medical errors. To facilitate the professional development of hospitalists, we seek articles focused on their professional development in community, academic, and administrative settings. Examples of leadership topics are managing physician performance, leading and managing change, and self‐evaluation. Teaching tips or descriptions of educational programs or curricula also are desired. For researchers, potential topics include descriptions of specific techniques used for surveys, meta‐analyses, economic evaluations, and statistical analyses.Penetrating point manuscripts, those that go beyond the cutting edge to explain the next potential breakthrough or intervention in the developing field of hospital medicine, may be authored by thought leaders inside and outside the health care field as well as by hospitalists with novel ideas. Equally vital, I want to share the illuminating perspectives of physicians, patients, and families of patients as they reflect on the experience of being in the hospitalhospitalists can enlighten us through their handoffs, and patients and their families can inform us about their view from the hospital bed.

Finally, never forget that this is your journal. Let me know what you like and what changes you think can make it better. Please e‐mail your suggestions, comments, criticisms, and ideas to us at JHMeditor@ hospitalmedicine.org. This is your chance to help shape the practice of hospital medicine and the future of hospital care. I look forward to your guidance. Together we can expand our knowledge and continue to grow in our careers.

The more you see the less you know

The less you find out as you grow

I knew much more then than I do now.

U2, City of Blinding Lights,

How to Dismantle an Atomic Bomb

- ,.The emerging role of “hospitalists” in the American health care system.N Engl J Med.1996;335:514–517.

- .The future of hospital medicine: evolution or revolution?Am J Med.2004;117:446–450.

- .Translational and clinical science—time for a new vision.N Engl J Med2005;35:1621‐1623.

- ,,,,, eds.The core competencies in hospital medicine: development and methodology.J Hosp Med.2006;1:48–56.

- ,,,,.How to use The Core Competencies in Hospital Medicine: A Framework for Curriculum Development.J Hosp Med.2006;1:57–67.

- .Hospital medicine: early successes and challenges ahead.J Hosp Med.2006;1:3–4.

- ,.The emerging role of “hospitalists” in the American health care system.N Engl J Med.1996;335:514–517.

- .The future of hospital medicine: evolution or revolution?Am J Med.2004;117:446–450.

- .Translational and clinical science—time for a new vision.N Engl J Med2005;35:1621‐1623.

- ,,,,, eds.The core competencies in hospital medicine: development and methodology.J Hosp Med.2006;1:48–56.

- ,,,,.How to use The Core Competencies in Hospital Medicine: A Framework for Curriculum Development.J Hosp Med.2006;1:57–67.

- .Hospital medicine: early successes and challenges ahead.J Hosp Med.2006;1:3–4.

Quality Tools: Root Cause Analysis (RCA) and Failure Modes and Effects Analysis (FMEA)

When we speak of “quality” in health care, we generally think of mortality outcomes or regulatory requirements that are mandated by the JCAHO (Joint Commission for Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations). But how do these relate to and impact our everyday lives as hospitalists? At the 8th Annual Meeting of SHM we presented a workshop on RCA and FMEA, taking a practical approach to illustrate how these two JCAHO required methodologies can improve patient care as well as improve the work environment for hospitalists by addressing the systemic issues that can compromise care.

The workshop starts by stepping into the life of a hospitalist and something we all fear: “Something bad happens. Then what?” Depending on the severity of the event, the options include peer review, notifying the Department Chief, calling the Risk Manager, calling your lawyer, or doing nothing. You’ve probably had many experiences when “something wasn’t quite right,” but often there is no obvious bad outcome or obvious solution, so we shrug our shoulders and say, “Oh well, we got lucky this time; no harm, no foul.” The problem is, there are recurring patterns to these types of events, and the same issues may affect the next patient, who may not be so lucky.

Defining “Something Bad”

These types of cases, which have outcomes ranging from no effect on the patient to death, may be approached several different ways. The terms “near miss” or “close call” refer to an incident where a mistake was made but caught in time, so no harm was done to the patient. An example of this is when a physician makes a mistake on a medication order, but it is caught and corrected by a pharmacist or nurse.

When adverse outcomes do occur, think about and define etiologies so that you identify and address underlying causes. Is the outcome an expected or unexpected complication of therapy? Was there an error involved? In asking these questions, remember that you can have harm without error and error without harm. Error is defined as “failure of a planned action to be completed as intended or use of a wrong plan to achieve an aim; the accumulation of errors results in accidents” (Kohn, et al). This definition points out that usually a chain of events rather than a single individual or event results in a bad outcome. The purpose of defining etiologies is not to assign blame but to identify underlying issues and surrounding circumstances that may have contributed to the adverse outcome.

Significant adverse events are called “sentinel events” and defined as an “unexpected occurrence involving death or serious physical or psychological injury, or the risk thereof. Serious injury specifically includes loss of limb or function” (JCAHO 1998).

How We Approach Error

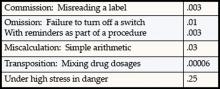

Unfortunately, as humans we are fallible and make errors quite reliably. Table 1 demonstrates types of errors and expected rates of errors. For example, we make errors of omission 0.01% of the time, but the good news is that with reminders or ticklers, we can reduce this rate to 0.003%. Unfortunately, when humans are under high stress in danger, research from the military indicates error rates of 25% (Salvendy 1997). In a complex ICU setting, researchers have documented an average of 178 activities per patient per day with an error rate of 0.95%. Despite an error rate of less than 1%, the yield of errors during the 4-month period of observation was still over 1000 errors, 29% of which were considered to have severe or potentially severe consequences (Donchin, et al).

The reality is that we err. Having the unrealistic expectations developed in medical training of being perfect in all our actions perpetuates the blame cycle when the inevitable mistake occurs, and it prevents us from implementing solutions that prevent errors from ever occurring or catching them before they cause harm.

RCA and FMEA Help Us Create Solutions That Make a Difference

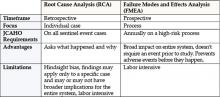

Briefly, Root Cause Analysis (RCA) is a retrospective investigation that is required by JCAHO after a sentinel event: “Root cause analysis is a process for identifying the basic or causal factor(s) that underlies variation in performance, including the occurrence or possible occurrence of a sentinel event. A root cause is that most fundamental reason a problem―a situation where performance does not meet expectations―has occurred” (JCAHO 1998). An RCA looks back in time at an event and asks the question “What

happened?” The utility of this methodology lies in the fact that it not only asks what happened but also asks “Why did this happen” rather than focus on “Who is to blame?” Some hospitals use this methodology for cases that are not sentinel events, because the knowledge gained from these investigations often uncovers system issues previously not known and that negatively impact many departments, not just the departments involved in a particular case.

Failure Modes and Effects Analysis (FMEA) is a prospective investigation aimed at identifying vulnerabilities and preventing failures in the future. It looks forward and asks what could go wrong? Performance of an FMEA is also required yearly by JCAHO and focuses on improving risky processes such as blood transfusions, chemotherapy, and other high risk medications.

Approaching a clinical case clearly demonstrates the differences between RCA and FMEA. Imagine a 72-year-old patient admitted to your hospital with findings of an acute abdomen requiring surgery. The patient is a smoker, with Type 2 diabetes and an admission blood sugar of 465, but no evidence of DKA. She normally takes an oral hypoglycemic to control her diabetes and an ACE inhibitor for high blood pressure but no other medications. She is taken to the OR emergently, where surgery seems to go well, and post-operatively is admitted to the ICU. Subsequently, her blood glucose ranges from 260 to 370 and is “controlled” with sliding scale insulin. Unfortunately, within 18 hours of surgery she suffers an MI and develops a postoperative wound infection 4 days after surgery. She eventually dies from sepsis.

An RCA of this case might reveal causal factors such as lack of use of a beta-blocker preoperatively and lack of use of IV insulin to lower her blood sugars to the 80–110 range. While possibly identifying the root cause of this adverse outcome, an RCA is limited by its hindsight bias and the labor-intensive nature of the investigation that may or may not have broad application, since it is an in-depth study of one case. However, RCA’s do have the salutary effects of building teamwork, identifying needed changes, and if carried out impartially without assigning blame can facilitate a culture of patient safety.

FMEA takes a different approach and proactively aims to prevent failure. It is a systematic method of identifying and preventing product and process failures before they occur. It does not require a specific case or adverse event. Rather, a high-risk process is chosen for study, and an interdisciplinary team asks the question “What can go wrong with this process and how can we prevent failures?” Considering the above case, imagine that before it ever occurred you as the hospitalist concerned with patient safety decided to conduct an FMEA on controlling blood sugar in the ICU or administering beta-blockers perioperatively to patients who are appropriate candidates.

For example, using FMEA methodology to study the process of intensive insulin therapy to achieve tight control of glucose in the ICU would identify potential barriers and failures preventing successful implementation. A significant risk encountered in achieving tight glucose control in the range of 80–110 includes hypoglycemia. Common pitfalls of insulin administration include administration and calculation errors that can result in 10-fold differences in doses of insulin. Other details of administration, such as type of IV tubing used and how the IV tubing is primed, can greatly affect the amount of insulin delivered to the patient and thus the glucose levels. If an inadequate amount of solution is flushed through to prime the tubing, the patient may receive saline rather than insulin for a few hours, resulting in higher-than-expected glucose levels and titration of insulin to higher doses. The result would then be an unexpectedly low glucose several hours later. Once failure modes such as these are identified, a fail-safe system can be designed so that failures are less likely to occur.

The advantages of FMEA include its focus on system design rather than on a single incident such as in RCA. By focusing on systems and processes, the learning and changes implemented are likely to impact a larger number of patients.

Summary and Discussion

To summarize, RCA is retrospective and dissects a case, while FMEA is prospective and dissects a process. It is important to remember that given the right set of circumstances, any physician can make a mistake. It makes sense to apply methodologies that probe into surrounding circumstances and contributing factors so that knowledge gained can be used to prevent the same mistakes from happening to different individuals and have broader impact on healthcare systems.

Resources

- www.patientsafety.gov: VA National Center for Patient Safety. Excellent website with very helpful, practical tools.

- www.ihi.org: Institute for Healthcare Improvement website. Has a nice FMEA toolkit.

- www.jcaho.com: The Joint Commission for Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations website. Has information on sentinel events and use of RCA.

Bibliography

- Kohn LT, Corrigan JM, Eds. To Err is Human. Building a Safer Helath System. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1999.

- Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations. Sentinel events: evaluating cause and planning improvement. 1998. Library of congress catalog number 97-80531.

- Salvendy G, ed. Handbook of Human Factors and Ergonomics. New York: John Wiley & Sons;1997:163

- Donchin Y, Gopher D, Olin M, et al. A look into the nature and causes of human errors in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 1995;23:294-300.

- McNutt R, Abrams R, Hasler S, et al. Determining medical error: three case reports. Eff Clin Pract. 2002;5:23-8.

- Senders JW. FMEA and RCA: the mantras of modern risk management. Qual Saf Health Care. 2004;13:249-50.

- Spath PL. Investigating Sentinel Events: How to Find and Resolve Root Causes. Forest Grove, OR: Brown Spath and Associates; 1997.

- Wald H, Shojania KG. Root cause analysis. In: Shojania KG, McDonald KM, Wachter RM, eds. Making Health Care Safer: A Critical Analysis of Patient Safety Practices. Evidence Report/Technology Assessment No. 43, AHRQ Publication No. 01-E058; July 2001. Available at http://www.ahrq.gov.

- Woodhouse S, Burney B, Coste K. To err is human: improving patient safety through failure mode and effect analysis. Clin leadersh Manag Rev. 2004;18:32-6.

When we speak of “quality” in health care, we generally think of mortality outcomes or regulatory requirements that are mandated by the JCAHO (Joint Commission for Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations). But how do these relate to and impact our everyday lives as hospitalists? At the 8th Annual Meeting of SHM we presented a workshop on RCA and FMEA, taking a practical approach to illustrate how these two JCAHO required methodologies can improve patient care as well as improve the work environment for hospitalists by addressing the systemic issues that can compromise care.

The workshop starts by stepping into the life of a hospitalist and something we all fear: “Something bad happens. Then what?” Depending on the severity of the event, the options include peer review, notifying the Department Chief, calling the Risk Manager, calling your lawyer, or doing nothing. You’ve probably had many experiences when “something wasn’t quite right,” but often there is no obvious bad outcome or obvious solution, so we shrug our shoulders and say, “Oh well, we got lucky this time; no harm, no foul.” The problem is, there are recurring patterns to these types of events, and the same issues may affect the next patient, who may not be so lucky.

Defining “Something Bad”

These types of cases, which have outcomes ranging from no effect on the patient to death, may be approached several different ways. The terms “near miss” or “close call” refer to an incident where a mistake was made but caught in time, so no harm was done to the patient. An example of this is when a physician makes a mistake on a medication order, but it is caught and corrected by a pharmacist or nurse.

When adverse outcomes do occur, think about and define etiologies so that you identify and address underlying causes. Is the outcome an expected or unexpected complication of therapy? Was there an error involved? In asking these questions, remember that you can have harm without error and error without harm. Error is defined as “failure of a planned action to be completed as intended or use of a wrong plan to achieve an aim; the accumulation of errors results in accidents” (Kohn, et al). This definition points out that usually a chain of events rather than a single individual or event results in a bad outcome. The purpose of defining etiologies is not to assign blame but to identify underlying issues and surrounding circumstances that may have contributed to the adverse outcome.

Significant adverse events are called “sentinel events” and defined as an “unexpected occurrence involving death or serious physical or psychological injury, or the risk thereof. Serious injury specifically includes loss of limb or function” (JCAHO 1998).

How We Approach Error

Unfortunately, as humans we are fallible and make errors quite reliably. Table 1 demonstrates types of errors and expected rates of errors. For example, we make errors of omission 0.01% of the time, but the good news is that with reminders or ticklers, we can reduce this rate to 0.003%. Unfortunately, when humans are under high stress in danger, research from the military indicates error rates of 25% (Salvendy 1997). In a complex ICU setting, researchers have documented an average of 178 activities per patient per day with an error rate of 0.95%. Despite an error rate of less than 1%, the yield of errors during the 4-month period of observation was still over 1000 errors, 29% of which were considered to have severe or potentially severe consequences (Donchin, et al).

The reality is that we err. Having the unrealistic expectations developed in medical training of being perfect in all our actions perpetuates the blame cycle when the inevitable mistake occurs, and it prevents us from implementing solutions that prevent errors from ever occurring or catching them before they cause harm.

RCA and FMEA Help Us Create Solutions That Make a Difference

Briefly, Root Cause Analysis (RCA) is a retrospective investigation that is required by JCAHO after a sentinel event: “Root cause analysis is a process for identifying the basic or causal factor(s) that underlies variation in performance, including the occurrence or possible occurrence of a sentinel event. A root cause is that most fundamental reason a problem―a situation where performance does not meet expectations―has occurred” (JCAHO 1998). An RCA looks back in time at an event and asks the question “What

happened?” The utility of this methodology lies in the fact that it not only asks what happened but also asks “Why did this happen” rather than focus on “Who is to blame?” Some hospitals use this methodology for cases that are not sentinel events, because the knowledge gained from these investigations often uncovers system issues previously not known and that negatively impact many departments, not just the departments involved in a particular case.

Failure Modes and Effects Analysis (FMEA) is a prospective investigation aimed at identifying vulnerabilities and preventing failures in the future. It looks forward and asks what could go wrong? Performance of an FMEA is also required yearly by JCAHO and focuses on improving risky processes such as blood transfusions, chemotherapy, and other high risk medications.

Approaching a clinical case clearly demonstrates the differences between RCA and FMEA. Imagine a 72-year-old patient admitted to your hospital with findings of an acute abdomen requiring surgery. The patient is a smoker, with Type 2 diabetes and an admission blood sugar of 465, but no evidence of DKA. She normally takes an oral hypoglycemic to control her diabetes and an ACE inhibitor for high blood pressure but no other medications. She is taken to the OR emergently, where surgery seems to go well, and post-operatively is admitted to the ICU. Subsequently, her blood glucose ranges from 260 to 370 and is “controlled” with sliding scale insulin. Unfortunately, within 18 hours of surgery she suffers an MI and develops a postoperative wound infection 4 days after surgery. She eventually dies from sepsis.

An RCA of this case might reveal causal factors such as lack of use of a beta-blocker preoperatively and lack of use of IV insulin to lower her blood sugars to the 80–110 range. While possibly identifying the root cause of this adverse outcome, an RCA is limited by its hindsight bias and the labor-intensive nature of the investigation that may or may not have broad application, since it is an in-depth study of one case. However, RCA’s do have the salutary effects of building teamwork, identifying needed changes, and if carried out impartially without assigning blame can facilitate a culture of patient safety.

FMEA takes a different approach and proactively aims to prevent failure. It is a systematic method of identifying and preventing product and process failures before they occur. It does not require a specific case or adverse event. Rather, a high-risk process is chosen for study, and an interdisciplinary team asks the question “What can go wrong with this process and how can we prevent failures?” Considering the above case, imagine that before it ever occurred you as the hospitalist concerned with patient safety decided to conduct an FMEA on controlling blood sugar in the ICU or administering beta-blockers perioperatively to patients who are appropriate candidates.

For example, using FMEA methodology to study the process of intensive insulin therapy to achieve tight control of glucose in the ICU would identify potential barriers and failures preventing successful implementation. A significant risk encountered in achieving tight glucose control in the range of 80–110 includes hypoglycemia. Common pitfalls of insulin administration include administration and calculation errors that can result in 10-fold differences in doses of insulin. Other details of administration, such as type of IV tubing used and how the IV tubing is primed, can greatly affect the amount of insulin delivered to the patient and thus the glucose levels. If an inadequate amount of solution is flushed through to prime the tubing, the patient may receive saline rather than insulin for a few hours, resulting in higher-than-expected glucose levels and titration of insulin to higher doses. The result would then be an unexpectedly low glucose several hours later. Once failure modes such as these are identified, a fail-safe system can be designed so that failures are less likely to occur.

The advantages of FMEA include its focus on system design rather than on a single incident such as in RCA. By focusing on systems and processes, the learning and changes implemented are likely to impact a larger number of patients.

Summary and Discussion

To summarize, RCA is retrospective and dissects a case, while FMEA is prospective and dissects a process. It is important to remember that given the right set of circumstances, any physician can make a mistake. It makes sense to apply methodologies that probe into surrounding circumstances and contributing factors so that knowledge gained can be used to prevent the same mistakes from happening to different individuals and have broader impact on healthcare systems.

Resources

- www.patientsafety.gov: VA National Center for Patient Safety. Excellent website with very helpful, practical tools.

- www.ihi.org: Institute for Healthcare Improvement website. Has a nice FMEA toolkit.

- www.jcaho.com: The Joint Commission for Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations website. Has information on sentinel events and use of RCA.

Bibliography

- Kohn LT, Corrigan JM, Eds. To Err is Human. Building a Safer Helath System. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1999.

- Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations. Sentinel events: evaluating cause and planning improvement. 1998. Library of congress catalog number 97-80531.

- Salvendy G, ed. Handbook of Human Factors and Ergonomics. New York: John Wiley & Sons;1997:163

- Donchin Y, Gopher D, Olin M, et al. A look into the nature and causes of human errors in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 1995;23:294-300.

- McNutt R, Abrams R, Hasler S, et al. Determining medical error: three case reports. Eff Clin Pract. 2002;5:23-8.

- Senders JW. FMEA and RCA: the mantras of modern risk management. Qual Saf Health Care. 2004;13:249-50.

- Spath PL. Investigating Sentinel Events: How to Find and Resolve Root Causes. Forest Grove, OR: Brown Spath and Associates; 1997.

- Wald H, Shojania KG. Root cause analysis. In: Shojania KG, McDonald KM, Wachter RM, eds. Making Health Care Safer: A Critical Analysis of Patient Safety Practices. Evidence Report/Technology Assessment No. 43, AHRQ Publication No. 01-E058; July 2001. Available at http://www.ahrq.gov.

- Woodhouse S, Burney B, Coste K. To err is human: improving patient safety through failure mode and effect analysis. Clin leadersh Manag Rev. 2004;18:32-6.

When we speak of “quality” in health care, we generally think of mortality outcomes or regulatory requirements that are mandated by the JCAHO (Joint Commission for Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations). But how do these relate to and impact our everyday lives as hospitalists? At the 8th Annual Meeting of SHM we presented a workshop on RCA and FMEA, taking a practical approach to illustrate how these two JCAHO required methodologies can improve patient care as well as improve the work environment for hospitalists by addressing the systemic issues that can compromise care.

The workshop starts by stepping into the life of a hospitalist and something we all fear: “Something bad happens. Then what?” Depending on the severity of the event, the options include peer review, notifying the Department Chief, calling the Risk Manager, calling your lawyer, or doing nothing. You’ve probably had many experiences when “something wasn’t quite right,” but often there is no obvious bad outcome or obvious solution, so we shrug our shoulders and say, “Oh well, we got lucky this time; no harm, no foul.” The problem is, there are recurring patterns to these types of events, and the same issues may affect the next patient, who may not be so lucky.

Defining “Something Bad”

These types of cases, which have outcomes ranging from no effect on the patient to death, may be approached several different ways. The terms “near miss” or “close call” refer to an incident where a mistake was made but caught in time, so no harm was done to the patient. An example of this is when a physician makes a mistake on a medication order, but it is caught and corrected by a pharmacist or nurse.

When adverse outcomes do occur, think about and define etiologies so that you identify and address underlying causes. Is the outcome an expected or unexpected complication of therapy? Was there an error involved? In asking these questions, remember that you can have harm without error and error without harm. Error is defined as “failure of a planned action to be completed as intended or use of a wrong plan to achieve an aim; the accumulation of errors results in accidents” (Kohn, et al). This definition points out that usually a chain of events rather than a single individual or event results in a bad outcome. The purpose of defining etiologies is not to assign blame but to identify underlying issues and surrounding circumstances that may have contributed to the adverse outcome.

Significant adverse events are called “sentinel events” and defined as an “unexpected occurrence involving death or serious physical or psychological injury, or the risk thereof. Serious injury specifically includes loss of limb or function” (JCAHO 1998).

How We Approach Error

Unfortunately, as humans we are fallible and make errors quite reliably. Table 1 demonstrates types of errors and expected rates of errors. For example, we make errors of omission 0.01% of the time, but the good news is that with reminders or ticklers, we can reduce this rate to 0.003%. Unfortunately, when humans are under high stress in danger, research from the military indicates error rates of 25% (Salvendy 1997). In a complex ICU setting, researchers have documented an average of 178 activities per patient per day with an error rate of 0.95%. Despite an error rate of less than 1%, the yield of errors during the 4-month period of observation was still over 1000 errors, 29% of which were considered to have severe or potentially severe consequences (Donchin, et al).

The reality is that we err. Having the unrealistic expectations developed in medical training of being perfect in all our actions perpetuates the blame cycle when the inevitable mistake occurs, and it prevents us from implementing solutions that prevent errors from ever occurring or catching them before they cause harm.

RCA and FMEA Help Us Create Solutions That Make a Difference

Briefly, Root Cause Analysis (RCA) is a retrospective investigation that is required by JCAHO after a sentinel event: “Root cause analysis is a process for identifying the basic or causal factor(s) that underlies variation in performance, including the occurrence or possible occurrence of a sentinel event. A root cause is that most fundamental reason a problem―a situation where performance does not meet expectations―has occurred” (JCAHO 1998). An RCA looks back in time at an event and asks the question “What

happened?” The utility of this methodology lies in the fact that it not only asks what happened but also asks “Why did this happen” rather than focus on “Who is to blame?” Some hospitals use this methodology for cases that are not sentinel events, because the knowledge gained from these investigations often uncovers system issues previously not known and that negatively impact many departments, not just the departments involved in a particular case.

Failure Modes and Effects Analysis (FMEA) is a prospective investigation aimed at identifying vulnerabilities and preventing failures in the future. It looks forward and asks what could go wrong? Performance of an FMEA is also required yearly by JCAHO and focuses on improving risky processes such as blood transfusions, chemotherapy, and other high risk medications.

Approaching a clinical case clearly demonstrates the differences between RCA and FMEA. Imagine a 72-year-old patient admitted to your hospital with findings of an acute abdomen requiring surgery. The patient is a smoker, with Type 2 diabetes and an admission blood sugar of 465, but no evidence of DKA. She normally takes an oral hypoglycemic to control her diabetes and an ACE inhibitor for high blood pressure but no other medications. She is taken to the OR emergently, where surgery seems to go well, and post-operatively is admitted to the ICU. Subsequently, her blood glucose ranges from 260 to 370 and is “controlled” with sliding scale insulin. Unfortunately, within 18 hours of surgery she suffers an MI and develops a postoperative wound infection 4 days after surgery. She eventually dies from sepsis.

An RCA of this case might reveal causal factors such as lack of use of a beta-blocker preoperatively and lack of use of IV insulin to lower her blood sugars to the 80–110 range. While possibly identifying the root cause of this adverse outcome, an RCA is limited by its hindsight bias and the labor-intensive nature of the investigation that may or may not have broad application, since it is an in-depth study of one case. However, RCA’s do have the salutary effects of building teamwork, identifying needed changes, and if carried out impartially without assigning blame can facilitate a culture of patient safety.

FMEA takes a different approach and proactively aims to prevent failure. It is a systematic method of identifying and preventing product and process failures before they occur. It does not require a specific case or adverse event. Rather, a high-risk process is chosen for study, and an interdisciplinary team asks the question “What can go wrong with this process and how can we prevent failures?” Considering the above case, imagine that before it ever occurred you as the hospitalist concerned with patient safety decided to conduct an FMEA on controlling blood sugar in the ICU or administering beta-blockers perioperatively to patients who are appropriate candidates.

For example, using FMEA methodology to study the process of intensive insulin therapy to achieve tight control of glucose in the ICU would identify potential barriers and failures preventing successful implementation. A significant risk encountered in achieving tight glucose control in the range of 80–110 includes hypoglycemia. Common pitfalls of insulin administration include administration and calculation errors that can result in 10-fold differences in doses of insulin. Other details of administration, such as type of IV tubing used and how the IV tubing is primed, can greatly affect the amount of insulin delivered to the patient and thus the glucose levels. If an inadequate amount of solution is flushed through to prime the tubing, the patient may receive saline rather than insulin for a few hours, resulting in higher-than-expected glucose levels and titration of insulin to higher doses. The result would then be an unexpectedly low glucose several hours later. Once failure modes such as these are identified, a fail-safe system can be designed so that failures are less likely to occur.

The advantages of FMEA include its focus on system design rather than on a single incident such as in RCA. By focusing on systems and processes, the learning and changes implemented are likely to impact a larger number of patients.

Summary and Discussion

To summarize, RCA is retrospective and dissects a case, while FMEA is prospective and dissects a process. It is important to remember that given the right set of circumstances, any physician can make a mistake. It makes sense to apply methodologies that probe into surrounding circumstances and contributing factors so that knowledge gained can be used to prevent the same mistakes from happening to different individuals and have broader impact on healthcare systems.

Resources

- www.patientsafety.gov: VA National Center for Patient Safety. Excellent website with very helpful, practical tools.

- www.ihi.org: Institute for Healthcare Improvement website. Has a nice FMEA toolkit.

- www.jcaho.com: The Joint Commission for Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations website. Has information on sentinel events and use of RCA.

Bibliography

- Kohn LT, Corrigan JM, Eds. To Err is Human. Building a Safer Helath System. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1999.

- Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations. Sentinel events: evaluating cause and planning improvement. 1998. Library of congress catalog number 97-80531.

- Salvendy G, ed. Handbook of Human Factors and Ergonomics. New York: John Wiley & Sons;1997:163

- Donchin Y, Gopher D, Olin M, et al. A look into the nature and causes of human errors in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 1995;23:294-300.

- McNutt R, Abrams R, Hasler S, et al. Determining medical error: three case reports. Eff Clin Pract. 2002;5:23-8.

- Senders JW. FMEA and RCA: the mantras of modern risk management. Qual Saf Health Care. 2004;13:249-50.

- Spath PL. Investigating Sentinel Events: How to Find and Resolve Root Causes. Forest Grove, OR: Brown Spath and Associates; 1997.

- Wald H, Shojania KG. Root cause analysis. In: Shojania KG, McDonald KM, Wachter RM, eds. Making Health Care Safer: A Critical Analysis of Patient Safety Practices. Evidence Report/Technology Assessment No. 43, AHRQ Publication No. 01-E058; July 2001. Available at http://www.ahrq.gov.