User login

A Patient's Perspective on Readmissions

Years into the national discourse on reducing readmissions, hospitals and providers are still struggling with how to sustainably reduce 30‐day readmissions.[1] All‐cause hospital readmission rates for Medicare benificiaries averaged 19% from 2007 through 2011 and showed only a modest improvement to 18.4% in 2012.[2] A review of 43 studies in 2011 concluded that no single intervention was reliably associated with reducing readmission rates.[3] However, although no institution has found a magic bullet for reducing readmissions, progress has been made. A 2014 meta‐analysis of randomized trials aimed at preventing 30‐day readmissions found that overall readmission interventions are effective, and that the most successful interventions are more complex in nature and focus on empowering patients to engage in self‐care after discharge.[4] Readmission reduction efforts for patients with specific diagnoses have also made gains. Among patients with heart failure, for instance, higher rates of early outpatient follow‐up and care‐transition interventions for high‐risk patients have been shown to reduce 30‐day readmissions.[5, 6]

An emerging, yet still underexplored, area in readmissions is the importance of evaluating patient perspectives. The patient has intimate knowledge of the circumstances surrounding their readmission and can be a valuable resource. This is particularly true given evidence that patient perspectives do not always align with those of providers.[7, 8] Coleman's Care Transitions Intervention was one of the earliest care‐transition models demonstrating value in engaging patients to become actively involved in their care.[9] Since then, others have begun to analyze transitions of care from the patient perspective, identifying patient‐reported needs in anticipation of discharge and after they are home.[10, 11, 12, 13, 14] However, still only a few studies have endeavored to gain a thorough understanding of the readmitted patient perspective.[7, 15, 16] These studies have already identified important issues such as lack of patient readiness for discharge and the need for additional advanced care planning and caregiver resources. A few smaller studies have interviewed readmitted patients with specific diagnoses and have also shed light on disease‐specific issues.[17, 18, 19, 20] Outside the field of readmissions, improving patient‐centered communication has been shown to reduce expenditures on diagnostic tests,[21, 22] increase adherence to treatment,[23] and improve health outcomes.[24, 25] It is time for us to incorporate the patient voice into all areas of care.

In 2014, our group published the results of a study aimed at understanding the patient perspective surrounding readmissions. In this study, 27% of patients believed their readmission could have been prevented. This opinion was associated with not feeling ready for discharge, not having a follow‐up appointment scheduled, and poor satisfaction with the discharging team.[7] A key observation in these initial interviews was that patients often expressed sentiments of relief rather than frustration when they returned to the hospital. With the results of this previous study in mind, we designed a more comprehensive evaluation to investigate why patients felt unprepared for discharge, explore reasons for and attitudes surrounding readmissions, and identify patient‐centered interventions that could prevent future readmissions.

METHODS

Study Design and Recruitment

We designed the study as an in‐person survey of readmitted patients. Over a 7‐month period (February 11, 2014September 8, 2014), we identified all patients readmitted within 30 days to general medicine and cardiology services through daily queries from the electronic health record. The study took place in a 540‐bed tertiary academic medical center, as well as a 266‐bed affiliated community hospital. We reviewed the discharge summary from the index admission and the history and physical documentation from the readmission for exclusion criteria. Patients were excluded if they were: (1) readmitted to the intensive care unit, (2) had a planned readmission, (3) received an organ transplant in the preceding 3 months, (4) did not speak English, or (5) had a physical or mental incapacity preventing interview and no family member or caregiver was available to interview.

Patient Interviews

Five trained study volunteers approached all eligible patients for an interview starting the day after the patient was readmitted. Prior to the start of the interview, we obtained verbal consent from all patients. Interviews typically lasted 10 to 30 minutes in the patient's hospital room. Caregivers and/or family members were allowed to respond to interview questions if the patient granted them permission or if the patient was unable to participate. The interviewers were not part of the patient's medical team and the patients could refuse the interview at any time. According to the University of California Los Angeles (UCLA) Institutional Review Board, this work met criteria for quality‐improvement activities and was deemed to be exempt.

The survey was comprised of 24 questions addressing causes, preventability, and attitudes toward readmissions, readiness for discharge, quality of the discharge process, outpatient resources, and follow‐up care (see Supporting Information in the online version of this article). These areas of focus were chosen based on a pilot study of 98 patient interviews in which these topics emerged as worthy of further investigation.[7] With regard to patient readiness for discharge, we investigated correlations between patient readiness and symptom resolution, pain control, discharge location, level of support at home, and concerns about independent self‐care after discharge.

Data Analysis

We administered the surveys, collected and managed the data using REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture) hosted at UCLA.[26] We collected demographic data, including race, ethnicity, and insurance status retrospectively though automated chart abstraction.

We summarized descriptive characteristics by mean and standard deviation (SD) for continuous variables (except for length of stay, which was summarized by median and range) and by proportions for categorical variables. To compare demographic variables between interviewed participants and those not interviewed (not available, not approached, refused, or excluded) we used Pearson 2 tests and Fisher exact tests for categorical variables and Student t tests for the only continuous variable, age. In evaluating patient readiness for discharge, we divided patients into groups of ready and not ready as determined by interview responses, then performed Pearson 2 tests and Fisher exact tests where appropriate.

For comparing the extent of burden and relief patients endorsed upon being readmitted, we subtracted the burden score (110) from the relief score (110) for each patient, resulting in a net relief score. We then performed a 1‐sample t test to determine whether the net relief was significantly different from 0. A P value of<0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using R version 3.0.2 (

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

Eight hundred nineteen patients were readmitted to general medicine and cardiology services over the 7‐month study period at both institutions. Two hundred thirty‐five patients (29%) were excluded based on the predetermined exclusion criteria, and 105 patients (13%) were not approached for interview due to time constraints. Of the 479 eligible patients approached for interview, 164 patients (34%) could not be interviewed because they were unavailable, and 85 patients (18%) refused. We interviewed 230 patients (48%). We conducted 115 interviews at our academic medical center and 115 at our community affiliate. The only significant demographic difference between interviewed and not‐interviewed patients was race (P=0.004).

Interviewed patients had a mean (SD) age of 63 (SD 20) years, and 45% were male. Sixty‐three percent of interviewees were white, 21% black, 8% Asian, and 8% other. The index admission median length of stay was 4 days, and the average time between admission and readmission was 13 days (Table 1). Seventy‐nine percent of the interviews were performed directly with the patient, and 21% were conducted predominantly with the patient's caregiver.

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| |

| Age, y, mean (SD) | 62.9 (20.2) |

| Female, n (%) | 127 (55.2) |

| Insurance status, n (%) | |

| Commercial | 36 (16.3) |

| Medi‐Cal/Medicaid | 31 (14.0) |

| Medicare | 123 (55.7) |

| Other | 5 (2.3) |

| UCLA managed care | 26 (11.8) |

| Missing | 9 |

| Race, n (%) | |

| Asian | 18 (7.9) |

| Black or African American | 48 (21.1) |

| Other/refused | 19 (8.3) |

| White or Caucasian | 143 (62.7) |

| Missing | 2 |

| Index length of stay, d, median (maximum, minimum) | 4 (1, 49) |

| Time between discharge and readmission, d, mean (SD) | 13 (9) |

| Discharge location following index admission, n (%) | |

| Home | 202 (88.2) |

| Skilled nursing facility | 3 (1.3) |

| Acute rehab facility | 17 (7.4) |

| Assisted living facility | 2 (0.9) |

| Other | 5 (2.2) |

| Missing | 1 |

Patient Readiness

Twenty‐eight percent of patients reported feeling unready for discharge from their index admission. Patients who felt that their readmission was preventable were significantly more likely to report feeling unready at the time of discharge compared to those who did not classify their readmission as preventable (53% vs 17%, P<0.01). Among patients who did not feel ready for discharge, over two‐thirds felt their symptoms were not adequately resolved. Conversely, among patients who did feel ready for discharge, only 8% felt their symptoms were not resolved (P<0.01). Patients who felt they were not ready for discharge were also significantly more likely to endorse poor pain control (43% vs 7%, P<0.01). The location of discharge (ie, home, rehab facility, or skilled nursing facility) and having someone to help take care of them at home did not significantly correlate with patient readiness. Over 80% of patients in both groups reported having someone to help at home, but patients who felt unready for discharge were significantly more likely to have concerns about taking care of themselves at home (54% vs 25%, P<0.001) (Table 2).

| All Participants, n=230 | Ready, n=164 | Not Ready, n=65 | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symptoms were resolved enough to leave the hospital, n=227 | 170 (74.9%) | 149 (92.0%) | 21 (32.3%) | <0.01 |

| Felt pain was under control when left the hospital, n=229 | 190 (83.0%) | 153 (93.3%) | 37 (56.9%) | <0.01 |

| Discharged to home following index admission, n=229 | 202 (88.2%) | 146 (89.6%) | 56 (86.2%) | 0.62 |

| If discharged home, had someone at home able to help, n=202 | 178 (88.1%) | 132 (90.4%) | 46 (82.1%) | 0.17 |

| If discharged home, had concerns about being able to take of themselves at home or not being strong enough to go home, n=202 | 67 (33.2%) | 37 (25.3%) | 30 (53.6%) | <0.01 |

| Thought something could have been done to prevent them from coming back to the hospital, n=228 | 75 (32.9%) | 35 (21.6%) | 39 (60.0%) | <0.01 |

Discharge Instructions

Twenty‐nine percent of patients did not recall a physician talking to them about their discharge, and 35% did not remember receiving and reviewing the discharge paperwork. Of those who read the discharge paperwork, 23% noted difficulty identifying contact phone numbers, and 22% could not locate warning symptoms indicating when to seek medical attention. Patients were able to identify medications and follow‐up appointments on the discharge paperwork a majority of the time (92% and 85%, respectively).

Ambulatory Resources and Utilization

Patients were asked about their access to outpatient resources as well as their reason(s) for returning to the hospital. Eighty‐five percent of patients reported having a primary care doctor that they would feel comfortable calling if their symptoms worsened at home. Of the patients who indicated that they were given a contact number by their discharging team, only 56% contacted a doctor before returning to the emergency room. One‐third of patients reported knowing where to obtain urgent or same‐day care besides the emergency room. Among those who did report knowledge of same‐day care centers, 89% still chose not to utilize them.

Attitudes About Readmission

To investigate the patient experience with readmissions, patients were asked to rate the extent of the burden they felt upon returning to the hospital on a scale of 1 to 10, where 1 was no burden and 10 was extreme burden. Patients were also asked to evaluate the extent of relief they felt upon readmission using the same scale. On average, patients rated their sense of relief 1.8 points higher than their sense of burden upon readmission to the hospital (7.7 [SD 2.8] vs 5.9 [SD 3.4], P<0.001). The relief of readmission was rated as equal to or greater than the burden of readmission in 79% of cases. Lastly, patients' mean (SD) overall satisfaction with their medical care was 8.5 (SD 2.0) on a scale of 1 to 10, where 1 was the least satisfied and 10 was the most satisfied a patient could imagine.

DISCUSSION

This study performs a comprehensive evaluation of the patient perspective on 30‐day readmissions. Our previous work indicated that patients associate preventable readmissions with lack of preparedness at the time of discharge.[7] This study further evaluates the basis of this association. We found that nearly 1 in 3 readmitted patients did not feel ready to leave the hospital at the time of initial discharge. Feelings of inadequate symptom resolution and poor pain control appear to be major contributors to this sentiment. Furthermore, although 88% of patients endorse having a caretaker at home, patients with concerns about taking care of themselves are more likely to feel unready at discharge. Presumably, when healthcare providers discharge patients, they believe that the patient is ready to be discharged. However, our findings suggest that often patients do not agree, highlighting a gap between the beliefs of patients and those of healthcare providers. Creating patient‐centered education on symptom management and engaging patients in developing skills for independent self‐care may minimize this gap and allow patients to feel more prepared at discharge. Future research investigating provider opinions and the steps providers take when there is a disagreement over discharge readiness would also be useful.

One way to enhance education at the time of discharge is through improvements in printed discharge instructions. Jha et al. previously showed that chart documentation of providing discharge instructions does not correlate with patients reporting receiving discharge instructions.[27] Our study echoes this finding, with only 65% of the patients remembering receiving and reviewing the discharge paperwork. Horwitz et al. have also previously demonstrated poor comprehension of discharge planning and postdischarge care among patients discharged from an academic medical center.[28] Ensuring that all patients understand and retain their discharge instructions is an essential step in improving the patient experience and potentially decreasing readmissions. Our surveys have illuminated potential shortcomings in our own center's discharge instructions. Interventions aimed at clarifying critical pieces of information on the discharge paperwork, such as warning symptoms, contact phone numbers and follow‐up appointments, could be especially helpful.

After discharge, our findings suggest that only about half of patients will call a physician before returning to the hospital. Furthermore, there is limited knowledge and poor utilization of same‐day treatment centers besides the emergency room. In previous studies, Long et al. found that frequently readmitted patients self‐triage to the emergency room because they believe primary care clinics cannot treat acute illness.[11] Another study concluded that low‐income patients prefer hospital care to ambulatory care because of a greater sense of trust in inpatient care.[29]

Our patients' attitudes about readmission may also be different from those of providers. For patients, coming back to the hospital is not a significant burden, and satisfaction with their medical care remains high despite readmission. Additional research is needed to further explore the complex emotions patients have when coming back to the hospital and why patients may not be as upset with returning to the hospital as providers may expect. Ultimately, if patients continue to feel more comfortable being hospitalized, there are few incentives for patients to stay out of the hospital, and readmission rates will remain elevated.

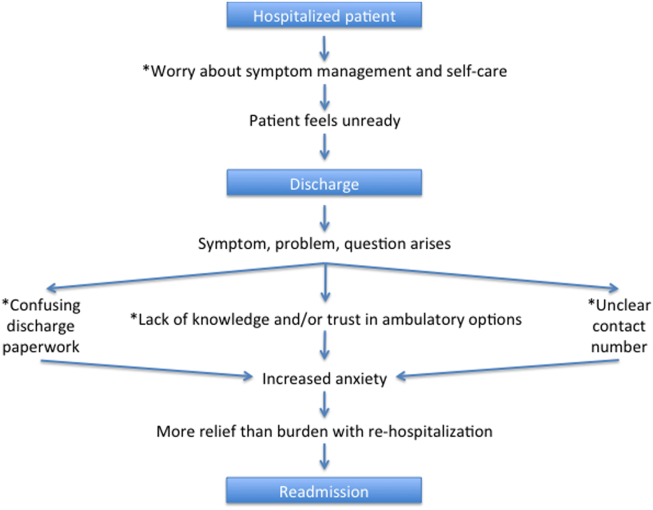

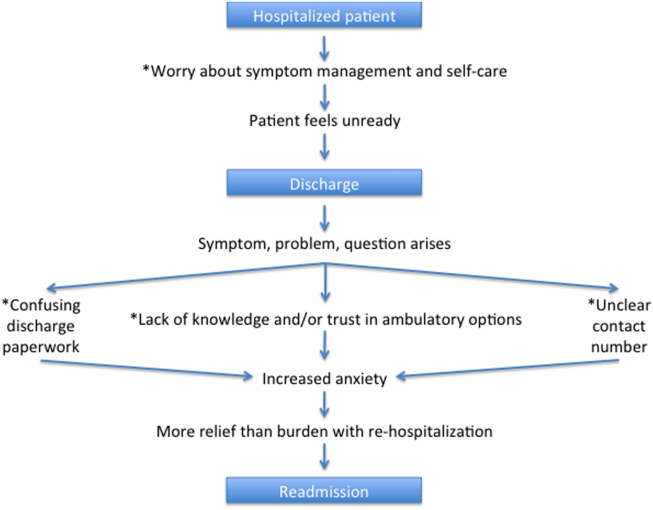

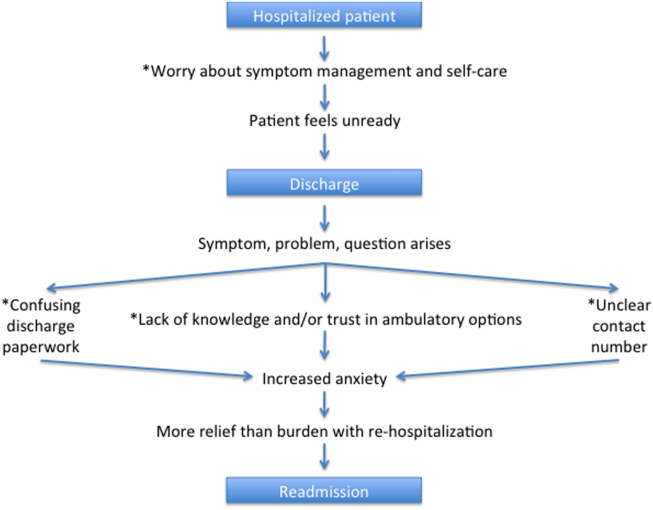

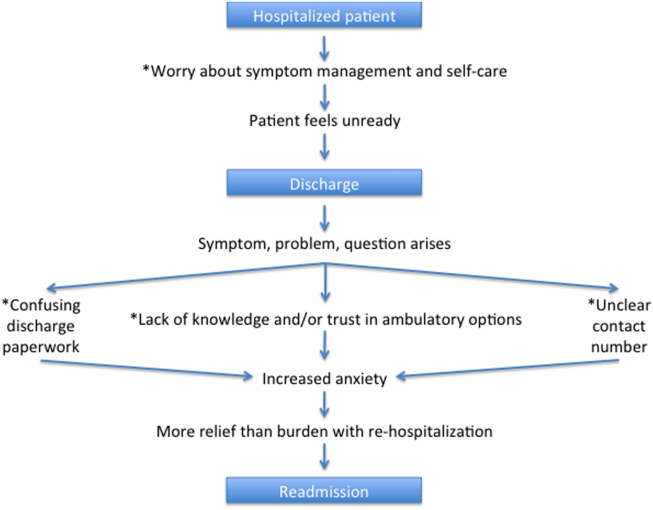

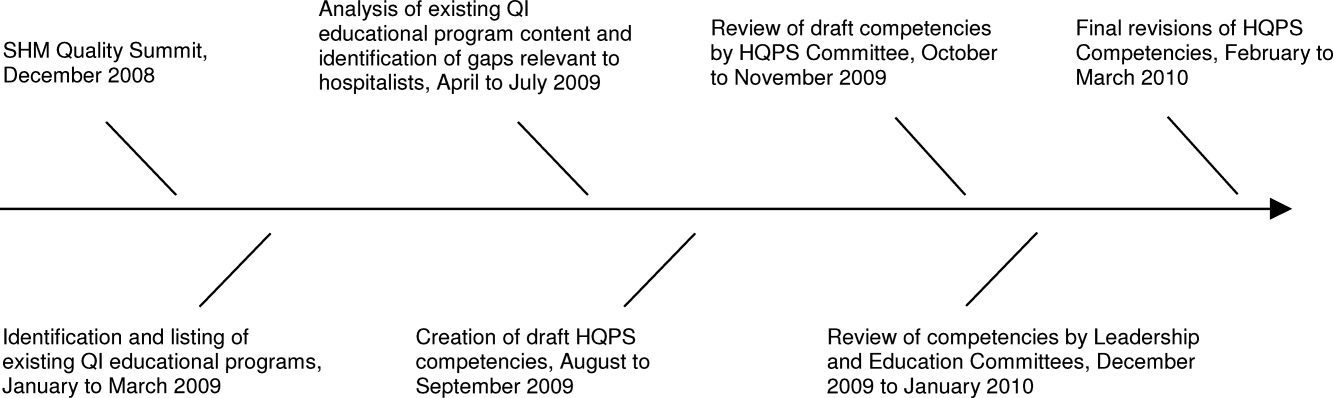

Based on our survey results we have hypothesized a potential framework for studying readmissions from a patient‐centered approach (Figure 1). This figure is not meant to imply causality, but rather to highlight a potential journey from discharge to readmission for a patient who does not feel ready to go home. This schema principally applies to patients who are worried about symptom management and/or self‐care before discharge and may not apply to everyone. Each asterisk in this framework represents an area where an intervention could be designed to improve the patient experience and possibly reduce readmissions. Such interventions should be centered around increasing patient education about symptom management and self‐care at the time of discharge, improving printed discharge instructions, increasing patient awareness of outpatient resources, enhancing communication after discharge, and changing patients' attitudes about readmissions.

This study's limitations include that it is a single‐institution study focusing on patients admitted to a large academic medical center and its partner community hospital. Only English‐speaking patients were included, and thus our results may not be generalizable to other populations. All patients were interviewed at the time of readmission, potentially introducing recall bias regarding their prior discharge. For example, patients might be more likely to state they were not ready for discharge once they have been readmitted to the hospital. Lastly, because there are only a few prior studies interviewing readmitted patients, our survey instrument was not previously validated. Nevertheless, we believe this study offers a unique view on 30‐day readmissions from the patient perspective, with a focus on identifying areas for quality‐improvement interventions.

In conclusion, this study has enabled us to understand readmissions from a patient‐centered perspective. This perspective helps to challenge provider assumptions and gives much‐needed insight into the patient experience. For example, prior to surveying patients, one might assume that if a patient has a caregiver at home, they are unlikely to have concerns about taking care of themselves. We now know this is not the case. Similarly, we have discovered sections of our discharge paperwork that are confusing. Additionally, this study has revealed that patient attitudes regarding readmission can vary significantly from provider attitudes. By exploring the patient perspective and creating a new transition framework, we have identified specific target areas for interventions that would be meaningful to patients. As the nation continues to strive to identify sustainable solutions to reduce readmissions, the way to redesign care must always start and end with the patient.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge Puneet Rana, James Haggerty‐Skeans, Jae Kim, Rhea Mathew, and Anna Do (UCLA volunteers) for helping to perform the patient interviews. We acknowledge Sandy Berry, MA (Senior Behavioral Scientist at RAND Corporation) for her help in reviewing our patient interview script. Additionally Anna Dermenchyan, RN, BSN (Senior Clinical Quality Specialist in the Department of Medicine at UCLA) provided significant administrative support.

Disclosures: This project was supported by a Patient Experience Grant from the Beryl Institute awarded to Jessica Howard‐Anderson, Sarah Lonowski, Ashley Busuttil, and Nasim Afsar‐manesh. Dr. Howard‐Anderson had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. All coauthors have seen and agree with the contents of the article. The article is not under review by any other publication. An earlier version of this work was written as a research report (not peer reviewed) for the Beryl Institute (available at:

- , . What will it take to move the needle on hospital readmissions? Am J Med Qual. 2013;29(4):357–359.

- , , , , , . Medicare readmission rates showed meaningful decline in 2012. Medicare Medicaid Res Rev. 2013;3(2):E1–E12.

- , , , , . Interventions to reduce 30‐day rehospitalization: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(8):520–528.

- , , , et al. Preventing 30‐day hospital readmissions: a systematic review and meta‐analysis of randomized trials. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(7):1095–1107.

- , , , et al. Relationship between early physician follow‐up and 30‐day readmission among Medicare beneficiaries hospitalized for heart failure. JAMA. 2010;303(17):1716–1722.

- , , , et al. Allocating scarce resources in real‐time to reduce heart failure readmissions: a prospective, controlled study. BMJ Qual Saf. 2013;22(12):998–1005.

- , , , , , . Readmissions in the era of patient engagement. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(11):1870–1872.

- , , , et al. Comparing perspectives of patients, caregivers, and clinicians on heart failure management [published online October 23, 2015]. J Card Fail. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2015.10.011.

- , , , . The care transitions intervention: results of a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(17):1822–1828.

- , , . Understanding rehospitalization risk: can hospital discharge be modified to reduce recurrent hospitalization? J Hosp Med. 2007;2(5):297–304.

- , , . Reasons for readmission in an underserved high‐risk population: a qualitative analysis of a series of inpatient interviews. BMJ Open. 2013;3(9):e003212.

- , , , , , . Improving care transitions: the patient perspective. J Health Commun. 2012;17(suppl 3):312–324.

- , , , et al. Challenges faced by patients with low socioeconomic status during the post‐hospital transition. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(2):283–289.

- , , , et al. “Missing pieces”—functional, social, and environmental barriers to recovery for vulnerable older adults transitioning from hospital to home. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62(8):1556–1561.

- , , , , , . Perceptions of readmitted patients on the transition from hospital to home. J Hosp Med. 2012;7(9):709–712.

- , , , et al. Factors contributing to all‐cause 30‐day readmissions: a structured case series across 18 hospitals. Med Care. 2012;50(7):599–605.

- , , . Reasons for readmission in heart failure: perspectives of patients, caregivers, cardiologists, and heart failure nurses. Heart Lung. 2009;38(5):427–434.

- , , , et al. Patient‐identified factors related to heart failure readmissions. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2013;6(2):171–177.

- , , , , . Early readmission among patients with diabetes: a qualitative assessment of contributing factors. J Diabetes Complications. 2014;28(6):869–873.

- , , , , . “Because I was sick”: seriously ill veterans' perspectives on reason for 30‐day readmissions. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63(3):537–542.

- , , , et al. The impact of patient‐centered care on outcomes. J Fam Pract. 2000;49(9):796–804.

- , , , et al. Patient‐centered communication and diagnostic testing. Ann Fam Med. 2005;3(5):415–421.

- , . Physician communication and patient adherence to treatment: a meta‐analysis. Med Care. 2009;47(8):826–834.

- , , , et al. Closing the loop: physician communication with diabetic patients who have low health literacy. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(1):83–90.

- , , , , . Patients' participation in medical care: effects on blood sugar control and quality of life in diabetes. J Gen Intern Med. 1988;3(5):448–457.

- , , , , , . Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata‐driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377–381.

- , , . Public reporting of discharge planning and rates of readmissions. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(27):2637–2645.

- , , , et al. Quality of discharge practices and patient understanding at an academic medical center. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(18):1715–1722

- , , , , , . Understanding why patients of low socioeconomic status prefer hospitals over ambulatory care. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32(7):1196–1203.

Years into the national discourse on reducing readmissions, hospitals and providers are still struggling with how to sustainably reduce 30‐day readmissions.[1] All‐cause hospital readmission rates for Medicare benificiaries averaged 19% from 2007 through 2011 and showed only a modest improvement to 18.4% in 2012.[2] A review of 43 studies in 2011 concluded that no single intervention was reliably associated with reducing readmission rates.[3] However, although no institution has found a magic bullet for reducing readmissions, progress has been made. A 2014 meta‐analysis of randomized trials aimed at preventing 30‐day readmissions found that overall readmission interventions are effective, and that the most successful interventions are more complex in nature and focus on empowering patients to engage in self‐care after discharge.[4] Readmission reduction efforts for patients with specific diagnoses have also made gains. Among patients with heart failure, for instance, higher rates of early outpatient follow‐up and care‐transition interventions for high‐risk patients have been shown to reduce 30‐day readmissions.[5, 6]

An emerging, yet still underexplored, area in readmissions is the importance of evaluating patient perspectives. The patient has intimate knowledge of the circumstances surrounding their readmission and can be a valuable resource. This is particularly true given evidence that patient perspectives do not always align with those of providers.[7, 8] Coleman's Care Transitions Intervention was one of the earliest care‐transition models demonstrating value in engaging patients to become actively involved in their care.[9] Since then, others have begun to analyze transitions of care from the patient perspective, identifying patient‐reported needs in anticipation of discharge and after they are home.[10, 11, 12, 13, 14] However, still only a few studies have endeavored to gain a thorough understanding of the readmitted patient perspective.[7, 15, 16] These studies have already identified important issues such as lack of patient readiness for discharge and the need for additional advanced care planning and caregiver resources. A few smaller studies have interviewed readmitted patients with specific diagnoses and have also shed light on disease‐specific issues.[17, 18, 19, 20] Outside the field of readmissions, improving patient‐centered communication has been shown to reduce expenditures on diagnostic tests,[21, 22] increase adherence to treatment,[23] and improve health outcomes.[24, 25] It is time for us to incorporate the patient voice into all areas of care.

In 2014, our group published the results of a study aimed at understanding the patient perspective surrounding readmissions. In this study, 27% of patients believed their readmission could have been prevented. This opinion was associated with not feeling ready for discharge, not having a follow‐up appointment scheduled, and poor satisfaction with the discharging team.[7] A key observation in these initial interviews was that patients often expressed sentiments of relief rather than frustration when they returned to the hospital. With the results of this previous study in mind, we designed a more comprehensive evaluation to investigate why patients felt unprepared for discharge, explore reasons for and attitudes surrounding readmissions, and identify patient‐centered interventions that could prevent future readmissions.

METHODS

Study Design and Recruitment

We designed the study as an in‐person survey of readmitted patients. Over a 7‐month period (February 11, 2014September 8, 2014), we identified all patients readmitted within 30 days to general medicine and cardiology services through daily queries from the electronic health record. The study took place in a 540‐bed tertiary academic medical center, as well as a 266‐bed affiliated community hospital. We reviewed the discharge summary from the index admission and the history and physical documentation from the readmission for exclusion criteria. Patients were excluded if they were: (1) readmitted to the intensive care unit, (2) had a planned readmission, (3) received an organ transplant in the preceding 3 months, (4) did not speak English, or (5) had a physical or mental incapacity preventing interview and no family member or caregiver was available to interview.

Patient Interviews

Five trained study volunteers approached all eligible patients for an interview starting the day after the patient was readmitted. Prior to the start of the interview, we obtained verbal consent from all patients. Interviews typically lasted 10 to 30 minutes in the patient's hospital room. Caregivers and/or family members were allowed to respond to interview questions if the patient granted them permission or if the patient was unable to participate. The interviewers were not part of the patient's medical team and the patients could refuse the interview at any time. According to the University of California Los Angeles (UCLA) Institutional Review Board, this work met criteria for quality‐improvement activities and was deemed to be exempt.

The survey was comprised of 24 questions addressing causes, preventability, and attitudes toward readmissions, readiness for discharge, quality of the discharge process, outpatient resources, and follow‐up care (see Supporting Information in the online version of this article). These areas of focus were chosen based on a pilot study of 98 patient interviews in which these topics emerged as worthy of further investigation.[7] With regard to patient readiness for discharge, we investigated correlations between patient readiness and symptom resolution, pain control, discharge location, level of support at home, and concerns about independent self‐care after discharge.

Data Analysis

We administered the surveys, collected and managed the data using REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture) hosted at UCLA.[26] We collected demographic data, including race, ethnicity, and insurance status retrospectively though automated chart abstraction.

We summarized descriptive characteristics by mean and standard deviation (SD) for continuous variables (except for length of stay, which was summarized by median and range) and by proportions for categorical variables. To compare demographic variables between interviewed participants and those not interviewed (not available, not approached, refused, or excluded) we used Pearson 2 tests and Fisher exact tests for categorical variables and Student t tests for the only continuous variable, age. In evaluating patient readiness for discharge, we divided patients into groups of ready and not ready as determined by interview responses, then performed Pearson 2 tests and Fisher exact tests where appropriate.

For comparing the extent of burden and relief patients endorsed upon being readmitted, we subtracted the burden score (110) from the relief score (110) for each patient, resulting in a net relief score. We then performed a 1‐sample t test to determine whether the net relief was significantly different from 0. A P value of<0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using R version 3.0.2 (

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

Eight hundred nineteen patients were readmitted to general medicine and cardiology services over the 7‐month study period at both institutions. Two hundred thirty‐five patients (29%) were excluded based on the predetermined exclusion criteria, and 105 patients (13%) were not approached for interview due to time constraints. Of the 479 eligible patients approached for interview, 164 patients (34%) could not be interviewed because they were unavailable, and 85 patients (18%) refused. We interviewed 230 patients (48%). We conducted 115 interviews at our academic medical center and 115 at our community affiliate. The only significant demographic difference between interviewed and not‐interviewed patients was race (P=0.004).

Interviewed patients had a mean (SD) age of 63 (SD 20) years, and 45% were male. Sixty‐three percent of interviewees were white, 21% black, 8% Asian, and 8% other. The index admission median length of stay was 4 days, and the average time between admission and readmission was 13 days (Table 1). Seventy‐nine percent of the interviews were performed directly with the patient, and 21% were conducted predominantly with the patient's caregiver.

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| |

| Age, y, mean (SD) | 62.9 (20.2) |

| Female, n (%) | 127 (55.2) |

| Insurance status, n (%) | |

| Commercial | 36 (16.3) |

| Medi‐Cal/Medicaid | 31 (14.0) |

| Medicare | 123 (55.7) |

| Other | 5 (2.3) |

| UCLA managed care | 26 (11.8) |

| Missing | 9 |

| Race, n (%) | |

| Asian | 18 (7.9) |

| Black or African American | 48 (21.1) |

| Other/refused | 19 (8.3) |

| White or Caucasian | 143 (62.7) |

| Missing | 2 |

| Index length of stay, d, median (maximum, minimum) | 4 (1, 49) |

| Time between discharge and readmission, d, mean (SD) | 13 (9) |

| Discharge location following index admission, n (%) | |

| Home | 202 (88.2) |

| Skilled nursing facility | 3 (1.3) |

| Acute rehab facility | 17 (7.4) |

| Assisted living facility | 2 (0.9) |

| Other | 5 (2.2) |

| Missing | 1 |

Patient Readiness

Twenty‐eight percent of patients reported feeling unready for discharge from their index admission. Patients who felt that their readmission was preventable were significantly more likely to report feeling unready at the time of discharge compared to those who did not classify their readmission as preventable (53% vs 17%, P<0.01). Among patients who did not feel ready for discharge, over two‐thirds felt their symptoms were not adequately resolved. Conversely, among patients who did feel ready for discharge, only 8% felt their symptoms were not resolved (P<0.01). Patients who felt they were not ready for discharge were also significantly more likely to endorse poor pain control (43% vs 7%, P<0.01). The location of discharge (ie, home, rehab facility, or skilled nursing facility) and having someone to help take care of them at home did not significantly correlate with patient readiness. Over 80% of patients in both groups reported having someone to help at home, but patients who felt unready for discharge were significantly more likely to have concerns about taking care of themselves at home (54% vs 25%, P<0.001) (Table 2).

| All Participants, n=230 | Ready, n=164 | Not Ready, n=65 | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symptoms were resolved enough to leave the hospital, n=227 | 170 (74.9%) | 149 (92.0%) | 21 (32.3%) | <0.01 |

| Felt pain was under control when left the hospital, n=229 | 190 (83.0%) | 153 (93.3%) | 37 (56.9%) | <0.01 |

| Discharged to home following index admission, n=229 | 202 (88.2%) | 146 (89.6%) | 56 (86.2%) | 0.62 |

| If discharged home, had someone at home able to help, n=202 | 178 (88.1%) | 132 (90.4%) | 46 (82.1%) | 0.17 |

| If discharged home, had concerns about being able to take of themselves at home or not being strong enough to go home, n=202 | 67 (33.2%) | 37 (25.3%) | 30 (53.6%) | <0.01 |

| Thought something could have been done to prevent them from coming back to the hospital, n=228 | 75 (32.9%) | 35 (21.6%) | 39 (60.0%) | <0.01 |

Discharge Instructions

Twenty‐nine percent of patients did not recall a physician talking to them about their discharge, and 35% did not remember receiving and reviewing the discharge paperwork. Of those who read the discharge paperwork, 23% noted difficulty identifying contact phone numbers, and 22% could not locate warning symptoms indicating when to seek medical attention. Patients were able to identify medications and follow‐up appointments on the discharge paperwork a majority of the time (92% and 85%, respectively).

Ambulatory Resources and Utilization

Patients were asked about their access to outpatient resources as well as their reason(s) for returning to the hospital. Eighty‐five percent of patients reported having a primary care doctor that they would feel comfortable calling if their symptoms worsened at home. Of the patients who indicated that they were given a contact number by their discharging team, only 56% contacted a doctor before returning to the emergency room. One‐third of patients reported knowing where to obtain urgent or same‐day care besides the emergency room. Among those who did report knowledge of same‐day care centers, 89% still chose not to utilize them.

Attitudes About Readmission

To investigate the patient experience with readmissions, patients were asked to rate the extent of the burden they felt upon returning to the hospital on a scale of 1 to 10, where 1 was no burden and 10 was extreme burden. Patients were also asked to evaluate the extent of relief they felt upon readmission using the same scale. On average, patients rated their sense of relief 1.8 points higher than their sense of burden upon readmission to the hospital (7.7 [SD 2.8] vs 5.9 [SD 3.4], P<0.001). The relief of readmission was rated as equal to or greater than the burden of readmission in 79% of cases. Lastly, patients' mean (SD) overall satisfaction with their medical care was 8.5 (SD 2.0) on a scale of 1 to 10, where 1 was the least satisfied and 10 was the most satisfied a patient could imagine.

DISCUSSION

This study performs a comprehensive evaluation of the patient perspective on 30‐day readmissions. Our previous work indicated that patients associate preventable readmissions with lack of preparedness at the time of discharge.[7] This study further evaluates the basis of this association. We found that nearly 1 in 3 readmitted patients did not feel ready to leave the hospital at the time of initial discharge. Feelings of inadequate symptom resolution and poor pain control appear to be major contributors to this sentiment. Furthermore, although 88% of patients endorse having a caretaker at home, patients with concerns about taking care of themselves are more likely to feel unready at discharge. Presumably, when healthcare providers discharge patients, they believe that the patient is ready to be discharged. However, our findings suggest that often patients do not agree, highlighting a gap between the beliefs of patients and those of healthcare providers. Creating patient‐centered education on symptom management and engaging patients in developing skills for independent self‐care may minimize this gap and allow patients to feel more prepared at discharge. Future research investigating provider opinions and the steps providers take when there is a disagreement over discharge readiness would also be useful.

One way to enhance education at the time of discharge is through improvements in printed discharge instructions. Jha et al. previously showed that chart documentation of providing discharge instructions does not correlate with patients reporting receiving discharge instructions.[27] Our study echoes this finding, with only 65% of the patients remembering receiving and reviewing the discharge paperwork. Horwitz et al. have also previously demonstrated poor comprehension of discharge planning and postdischarge care among patients discharged from an academic medical center.[28] Ensuring that all patients understand and retain their discharge instructions is an essential step in improving the patient experience and potentially decreasing readmissions. Our surveys have illuminated potential shortcomings in our own center's discharge instructions. Interventions aimed at clarifying critical pieces of information on the discharge paperwork, such as warning symptoms, contact phone numbers and follow‐up appointments, could be especially helpful.

After discharge, our findings suggest that only about half of patients will call a physician before returning to the hospital. Furthermore, there is limited knowledge and poor utilization of same‐day treatment centers besides the emergency room. In previous studies, Long et al. found that frequently readmitted patients self‐triage to the emergency room because they believe primary care clinics cannot treat acute illness.[11] Another study concluded that low‐income patients prefer hospital care to ambulatory care because of a greater sense of trust in inpatient care.[29]

Our patients' attitudes about readmission may also be different from those of providers. For patients, coming back to the hospital is not a significant burden, and satisfaction with their medical care remains high despite readmission. Additional research is needed to further explore the complex emotions patients have when coming back to the hospital and why patients may not be as upset with returning to the hospital as providers may expect. Ultimately, if patients continue to feel more comfortable being hospitalized, there are few incentives for patients to stay out of the hospital, and readmission rates will remain elevated.

Based on our survey results we have hypothesized a potential framework for studying readmissions from a patient‐centered approach (Figure 1). This figure is not meant to imply causality, but rather to highlight a potential journey from discharge to readmission for a patient who does not feel ready to go home. This schema principally applies to patients who are worried about symptom management and/or self‐care before discharge and may not apply to everyone. Each asterisk in this framework represents an area where an intervention could be designed to improve the patient experience and possibly reduce readmissions. Such interventions should be centered around increasing patient education about symptom management and self‐care at the time of discharge, improving printed discharge instructions, increasing patient awareness of outpatient resources, enhancing communication after discharge, and changing patients' attitudes about readmissions.

This study's limitations include that it is a single‐institution study focusing on patients admitted to a large academic medical center and its partner community hospital. Only English‐speaking patients were included, and thus our results may not be generalizable to other populations. All patients were interviewed at the time of readmission, potentially introducing recall bias regarding their prior discharge. For example, patients might be more likely to state they were not ready for discharge once they have been readmitted to the hospital. Lastly, because there are only a few prior studies interviewing readmitted patients, our survey instrument was not previously validated. Nevertheless, we believe this study offers a unique view on 30‐day readmissions from the patient perspective, with a focus on identifying areas for quality‐improvement interventions.

In conclusion, this study has enabled us to understand readmissions from a patient‐centered perspective. This perspective helps to challenge provider assumptions and gives much‐needed insight into the patient experience. For example, prior to surveying patients, one might assume that if a patient has a caregiver at home, they are unlikely to have concerns about taking care of themselves. We now know this is not the case. Similarly, we have discovered sections of our discharge paperwork that are confusing. Additionally, this study has revealed that patient attitudes regarding readmission can vary significantly from provider attitudes. By exploring the patient perspective and creating a new transition framework, we have identified specific target areas for interventions that would be meaningful to patients. As the nation continues to strive to identify sustainable solutions to reduce readmissions, the way to redesign care must always start and end with the patient.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge Puneet Rana, James Haggerty‐Skeans, Jae Kim, Rhea Mathew, and Anna Do (UCLA volunteers) for helping to perform the patient interviews. We acknowledge Sandy Berry, MA (Senior Behavioral Scientist at RAND Corporation) for her help in reviewing our patient interview script. Additionally Anna Dermenchyan, RN, BSN (Senior Clinical Quality Specialist in the Department of Medicine at UCLA) provided significant administrative support.

Disclosures: This project was supported by a Patient Experience Grant from the Beryl Institute awarded to Jessica Howard‐Anderson, Sarah Lonowski, Ashley Busuttil, and Nasim Afsar‐manesh. Dr. Howard‐Anderson had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. All coauthors have seen and agree with the contents of the article. The article is not under review by any other publication. An earlier version of this work was written as a research report (not peer reviewed) for the Beryl Institute (available at:

Years into the national discourse on reducing readmissions, hospitals and providers are still struggling with how to sustainably reduce 30‐day readmissions.[1] All‐cause hospital readmission rates for Medicare benificiaries averaged 19% from 2007 through 2011 and showed only a modest improvement to 18.4% in 2012.[2] A review of 43 studies in 2011 concluded that no single intervention was reliably associated with reducing readmission rates.[3] However, although no institution has found a magic bullet for reducing readmissions, progress has been made. A 2014 meta‐analysis of randomized trials aimed at preventing 30‐day readmissions found that overall readmission interventions are effective, and that the most successful interventions are more complex in nature and focus on empowering patients to engage in self‐care after discharge.[4] Readmission reduction efforts for patients with specific diagnoses have also made gains. Among patients with heart failure, for instance, higher rates of early outpatient follow‐up and care‐transition interventions for high‐risk patients have been shown to reduce 30‐day readmissions.[5, 6]

An emerging, yet still underexplored, area in readmissions is the importance of evaluating patient perspectives. The patient has intimate knowledge of the circumstances surrounding their readmission and can be a valuable resource. This is particularly true given evidence that patient perspectives do not always align with those of providers.[7, 8] Coleman's Care Transitions Intervention was one of the earliest care‐transition models demonstrating value in engaging patients to become actively involved in their care.[9] Since then, others have begun to analyze transitions of care from the patient perspective, identifying patient‐reported needs in anticipation of discharge and after they are home.[10, 11, 12, 13, 14] However, still only a few studies have endeavored to gain a thorough understanding of the readmitted patient perspective.[7, 15, 16] These studies have already identified important issues such as lack of patient readiness for discharge and the need for additional advanced care planning and caregiver resources. A few smaller studies have interviewed readmitted patients with specific diagnoses and have also shed light on disease‐specific issues.[17, 18, 19, 20] Outside the field of readmissions, improving patient‐centered communication has been shown to reduce expenditures on diagnostic tests,[21, 22] increase adherence to treatment,[23] and improve health outcomes.[24, 25] It is time for us to incorporate the patient voice into all areas of care.

In 2014, our group published the results of a study aimed at understanding the patient perspective surrounding readmissions. In this study, 27% of patients believed their readmission could have been prevented. This opinion was associated with not feeling ready for discharge, not having a follow‐up appointment scheduled, and poor satisfaction with the discharging team.[7] A key observation in these initial interviews was that patients often expressed sentiments of relief rather than frustration when they returned to the hospital. With the results of this previous study in mind, we designed a more comprehensive evaluation to investigate why patients felt unprepared for discharge, explore reasons for and attitudes surrounding readmissions, and identify patient‐centered interventions that could prevent future readmissions.

METHODS

Study Design and Recruitment

We designed the study as an in‐person survey of readmitted patients. Over a 7‐month period (February 11, 2014September 8, 2014), we identified all patients readmitted within 30 days to general medicine and cardiology services through daily queries from the electronic health record. The study took place in a 540‐bed tertiary academic medical center, as well as a 266‐bed affiliated community hospital. We reviewed the discharge summary from the index admission and the history and physical documentation from the readmission for exclusion criteria. Patients were excluded if they were: (1) readmitted to the intensive care unit, (2) had a planned readmission, (3) received an organ transplant in the preceding 3 months, (4) did not speak English, or (5) had a physical or mental incapacity preventing interview and no family member or caregiver was available to interview.

Patient Interviews

Five trained study volunteers approached all eligible patients for an interview starting the day after the patient was readmitted. Prior to the start of the interview, we obtained verbal consent from all patients. Interviews typically lasted 10 to 30 minutes in the patient's hospital room. Caregivers and/or family members were allowed to respond to interview questions if the patient granted them permission or if the patient was unable to participate. The interviewers were not part of the patient's medical team and the patients could refuse the interview at any time. According to the University of California Los Angeles (UCLA) Institutional Review Board, this work met criteria for quality‐improvement activities and was deemed to be exempt.

The survey was comprised of 24 questions addressing causes, preventability, and attitudes toward readmissions, readiness for discharge, quality of the discharge process, outpatient resources, and follow‐up care (see Supporting Information in the online version of this article). These areas of focus were chosen based on a pilot study of 98 patient interviews in which these topics emerged as worthy of further investigation.[7] With regard to patient readiness for discharge, we investigated correlations between patient readiness and symptom resolution, pain control, discharge location, level of support at home, and concerns about independent self‐care after discharge.

Data Analysis

We administered the surveys, collected and managed the data using REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture) hosted at UCLA.[26] We collected demographic data, including race, ethnicity, and insurance status retrospectively though automated chart abstraction.

We summarized descriptive characteristics by mean and standard deviation (SD) for continuous variables (except for length of stay, which was summarized by median and range) and by proportions for categorical variables. To compare demographic variables between interviewed participants and those not interviewed (not available, not approached, refused, or excluded) we used Pearson 2 tests and Fisher exact tests for categorical variables and Student t tests for the only continuous variable, age. In evaluating patient readiness for discharge, we divided patients into groups of ready and not ready as determined by interview responses, then performed Pearson 2 tests and Fisher exact tests where appropriate.

For comparing the extent of burden and relief patients endorsed upon being readmitted, we subtracted the burden score (110) from the relief score (110) for each patient, resulting in a net relief score. We then performed a 1‐sample t test to determine whether the net relief was significantly different from 0. A P value of<0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using R version 3.0.2 (

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

Eight hundred nineteen patients were readmitted to general medicine and cardiology services over the 7‐month study period at both institutions. Two hundred thirty‐five patients (29%) were excluded based on the predetermined exclusion criteria, and 105 patients (13%) were not approached for interview due to time constraints. Of the 479 eligible patients approached for interview, 164 patients (34%) could not be interviewed because they were unavailable, and 85 patients (18%) refused. We interviewed 230 patients (48%). We conducted 115 interviews at our academic medical center and 115 at our community affiliate. The only significant demographic difference between interviewed and not‐interviewed patients was race (P=0.004).

Interviewed patients had a mean (SD) age of 63 (SD 20) years, and 45% were male. Sixty‐three percent of interviewees were white, 21% black, 8% Asian, and 8% other. The index admission median length of stay was 4 days, and the average time between admission and readmission was 13 days (Table 1). Seventy‐nine percent of the interviews were performed directly with the patient, and 21% were conducted predominantly with the patient's caregiver.

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| |

| Age, y, mean (SD) | 62.9 (20.2) |

| Female, n (%) | 127 (55.2) |

| Insurance status, n (%) | |

| Commercial | 36 (16.3) |

| Medi‐Cal/Medicaid | 31 (14.0) |

| Medicare | 123 (55.7) |

| Other | 5 (2.3) |

| UCLA managed care | 26 (11.8) |

| Missing | 9 |

| Race, n (%) | |

| Asian | 18 (7.9) |

| Black or African American | 48 (21.1) |

| Other/refused | 19 (8.3) |

| White or Caucasian | 143 (62.7) |

| Missing | 2 |

| Index length of stay, d, median (maximum, minimum) | 4 (1, 49) |

| Time between discharge and readmission, d, mean (SD) | 13 (9) |

| Discharge location following index admission, n (%) | |

| Home | 202 (88.2) |

| Skilled nursing facility | 3 (1.3) |

| Acute rehab facility | 17 (7.4) |

| Assisted living facility | 2 (0.9) |

| Other | 5 (2.2) |

| Missing | 1 |

Patient Readiness

Twenty‐eight percent of patients reported feeling unready for discharge from their index admission. Patients who felt that their readmission was preventable were significantly more likely to report feeling unready at the time of discharge compared to those who did not classify their readmission as preventable (53% vs 17%, P<0.01). Among patients who did not feel ready for discharge, over two‐thirds felt their symptoms were not adequately resolved. Conversely, among patients who did feel ready for discharge, only 8% felt their symptoms were not resolved (P<0.01). Patients who felt they were not ready for discharge were also significantly more likely to endorse poor pain control (43% vs 7%, P<0.01). The location of discharge (ie, home, rehab facility, or skilled nursing facility) and having someone to help take care of them at home did not significantly correlate with patient readiness. Over 80% of patients in both groups reported having someone to help at home, but patients who felt unready for discharge were significantly more likely to have concerns about taking care of themselves at home (54% vs 25%, P<0.001) (Table 2).

| All Participants, n=230 | Ready, n=164 | Not Ready, n=65 | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symptoms were resolved enough to leave the hospital, n=227 | 170 (74.9%) | 149 (92.0%) | 21 (32.3%) | <0.01 |

| Felt pain was under control when left the hospital, n=229 | 190 (83.0%) | 153 (93.3%) | 37 (56.9%) | <0.01 |

| Discharged to home following index admission, n=229 | 202 (88.2%) | 146 (89.6%) | 56 (86.2%) | 0.62 |

| If discharged home, had someone at home able to help, n=202 | 178 (88.1%) | 132 (90.4%) | 46 (82.1%) | 0.17 |

| If discharged home, had concerns about being able to take of themselves at home or not being strong enough to go home, n=202 | 67 (33.2%) | 37 (25.3%) | 30 (53.6%) | <0.01 |

| Thought something could have been done to prevent them from coming back to the hospital, n=228 | 75 (32.9%) | 35 (21.6%) | 39 (60.0%) | <0.01 |

Discharge Instructions

Twenty‐nine percent of patients did not recall a physician talking to them about their discharge, and 35% did not remember receiving and reviewing the discharge paperwork. Of those who read the discharge paperwork, 23% noted difficulty identifying contact phone numbers, and 22% could not locate warning symptoms indicating when to seek medical attention. Patients were able to identify medications and follow‐up appointments on the discharge paperwork a majority of the time (92% and 85%, respectively).

Ambulatory Resources and Utilization

Patients were asked about their access to outpatient resources as well as their reason(s) for returning to the hospital. Eighty‐five percent of patients reported having a primary care doctor that they would feel comfortable calling if their symptoms worsened at home. Of the patients who indicated that they were given a contact number by their discharging team, only 56% contacted a doctor before returning to the emergency room. One‐third of patients reported knowing where to obtain urgent or same‐day care besides the emergency room. Among those who did report knowledge of same‐day care centers, 89% still chose not to utilize them.

Attitudes About Readmission

To investigate the patient experience with readmissions, patients were asked to rate the extent of the burden they felt upon returning to the hospital on a scale of 1 to 10, where 1 was no burden and 10 was extreme burden. Patients were also asked to evaluate the extent of relief they felt upon readmission using the same scale. On average, patients rated their sense of relief 1.8 points higher than their sense of burden upon readmission to the hospital (7.7 [SD 2.8] vs 5.9 [SD 3.4], P<0.001). The relief of readmission was rated as equal to or greater than the burden of readmission in 79% of cases. Lastly, patients' mean (SD) overall satisfaction with their medical care was 8.5 (SD 2.0) on a scale of 1 to 10, where 1 was the least satisfied and 10 was the most satisfied a patient could imagine.

DISCUSSION

This study performs a comprehensive evaluation of the patient perspective on 30‐day readmissions. Our previous work indicated that patients associate preventable readmissions with lack of preparedness at the time of discharge.[7] This study further evaluates the basis of this association. We found that nearly 1 in 3 readmitted patients did not feel ready to leave the hospital at the time of initial discharge. Feelings of inadequate symptom resolution and poor pain control appear to be major contributors to this sentiment. Furthermore, although 88% of patients endorse having a caretaker at home, patients with concerns about taking care of themselves are more likely to feel unready at discharge. Presumably, when healthcare providers discharge patients, they believe that the patient is ready to be discharged. However, our findings suggest that often patients do not agree, highlighting a gap between the beliefs of patients and those of healthcare providers. Creating patient‐centered education on symptom management and engaging patients in developing skills for independent self‐care may minimize this gap and allow patients to feel more prepared at discharge. Future research investigating provider opinions and the steps providers take when there is a disagreement over discharge readiness would also be useful.

One way to enhance education at the time of discharge is through improvements in printed discharge instructions. Jha et al. previously showed that chart documentation of providing discharge instructions does not correlate with patients reporting receiving discharge instructions.[27] Our study echoes this finding, with only 65% of the patients remembering receiving and reviewing the discharge paperwork. Horwitz et al. have also previously demonstrated poor comprehension of discharge planning and postdischarge care among patients discharged from an academic medical center.[28] Ensuring that all patients understand and retain their discharge instructions is an essential step in improving the patient experience and potentially decreasing readmissions. Our surveys have illuminated potential shortcomings in our own center's discharge instructions. Interventions aimed at clarifying critical pieces of information on the discharge paperwork, such as warning symptoms, contact phone numbers and follow‐up appointments, could be especially helpful.

After discharge, our findings suggest that only about half of patients will call a physician before returning to the hospital. Furthermore, there is limited knowledge and poor utilization of same‐day treatment centers besides the emergency room. In previous studies, Long et al. found that frequently readmitted patients self‐triage to the emergency room because they believe primary care clinics cannot treat acute illness.[11] Another study concluded that low‐income patients prefer hospital care to ambulatory care because of a greater sense of trust in inpatient care.[29]

Our patients' attitudes about readmission may also be different from those of providers. For patients, coming back to the hospital is not a significant burden, and satisfaction with their medical care remains high despite readmission. Additional research is needed to further explore the complex emotions patients have when coming back to the hospital and why patients may not be as upset with returning to the hospital as providers may expect. Ultimately, if patients continue to feel more comfortable being hospitalized, there are few incentives for patients to stay out of the hospital, and readmission rates will remain elevated.

Based on our survey results we have hypothesized a potential framework for studying readmissions from a patient‐centered approach (Figure 1). This figure is not meant to imply causality, but rather to highlight a potential journey from discharge to readmission for a patient who does not feel ready to go home. This schema principally applies to patients who are worried about symptom management and/or self‐care before discharge and may not apply to everyone. Each asterisk in this framework represents an area where an intervention could be designed to improve the patient experience and possibly reduce readmissions. Such interventions should be centered around increasing patient education about symptom management and self‐care at the time of discharge, improving printed discharge instructions, increasing patient awareness of outpatient resources, enhancing communication after discharge, and changing patients' attitudes about readmissions.

This study's limitations include that it is a single‐institution study focusing on patients admitted to a large academic medical center and its partner community hospital. Only English‐speaking patients were included, and thus our results may not be generalizable to other populations. All patients were interviewed at the time of readmission, potentially introducing recall bias regarding their prior discharge. For example, patients might be more likely to state they were not ready for discharge once they have been readmitted to the hospital. Lastly, because there are only a few prior studies interviewing readmitted patients, our survey instrument was not previously validated. Nevertheless, we believe this study offers a unique view on 30‐day readmissions from the patient perspective, with a focus on identifying areas for quality‐improvement interventions.

In conclusion, this study has enabled us to understand readmissions from a patient‐centered perspective. This perspective helps to challenge provider assumptions and gives much‐needed insight into the patient experience. For example, prior to surveying patients, one might assume that if a patient has a caregiver at home, they are unlikely to have concerns about taking care of themselves. We now know this is not the case. Similarly, we have discovered sections of our discharge paperwork that are confusing. Additionally, this study has revealed that patient attitudes regarding readmission can vary significantly from provider attitudes. By exploring the patient perspective and creating a new transition framework, we have identified specific target areas for interventions that would be meaningful to patients. As the nation continues to strive to identify sustainable solutions to reduce readmissions, the way to redesign care must always start and end with the patient.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge Puneet Rana, James Haggerty‐Skeans, Jae Kim, Rhea Mathew, and Anna Do (UCLA volunteers) for helping to perform the patient interviews. We acknowledge Sandy Berry, MA (Senior Behavioral Scientist at RAND Corporation) for her help in reviewing our patient interview script. Additionally Anna Dermenchyan, RN, BSN (Senior Clinical Quality Specialist in the Department of Medicine at UCLA) provided significant administrative support.

Disclosures: This project was supported by a Patient Experience Grant from the Beryl Institute awarded to Jessica Howard‐Anderson, Sarah Lonowski, Ashley Busuttil, and Nasim Afsar‐manesh. Dr. Howard‐Anderson had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. All coauthors have seen and agree with the contents of the article. The article is not under review by any other publication. An earlier version of this work was written as a research report (not peer reviewed) for the Beryl Institute (available at:

- , . What will it take to move the needle on hospital readmissions? Am J Med Qual. 2013;29(4):357–359.

- , , , , , . Medicare readmission rates showed meaningful decline in 2012. Medicare Medicaid Res Rev. 2013;3(2):E1–E12.

- , , , , . Interventions to reduce 30‐day rehospitalization: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(8):520–528.

- , , , et al. Preventing 30‐day hospital readmissions: a systematic review and meta‐analysis of randomized trials. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(7):1095–1107.

- , , , et al. Relationship between early physician follow‐up and 30‐day readmission among Medicare beneficiaries hospitalized for heart failure. JAMA. 2010;303(17):1716–1722.

- , , , et al. Allocating scarce resources in real‐time to reduce heart failure readmissions: a prospective, controlled study. BMJ Qual Saf. 2013;22(12):998–1005.

- , , , , , . Readmissions in the era of patient engagement. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(11):1870–1872.

- , , , et al. Comparing perspectives of patients, caregivers, and clinicians on heart failure management [published online October 23, 2015]. J Card Fail. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2015.10.011.

- , , , . The care transitions intervention: results of a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(17):1822–1828.

- , , . Understanding rehospitalization risk: can hospital discharge be modified to reduce recurrent hospitalization? J Hosp Med. 2007;2(5):297–304.

- , , . Reasons for readmission in an underserved high‐risk population: a qualitative analysis of a series of inpatient interviews. BMJ Open. 2013;3(9):e003212.

- , , , , , . Improving care transitions: the patient perspective. J Health Commun. 2012;17(suppl 3):312–324.

- , , , et al. Challenges faced by patients with low socioeconomic status during the post‐hospital transition. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(2):283–289.

- , , , et al. “Missing pieces”—functional, social, and environmental barriers to recovery for vulnerable older adults transitioning from hospital to home. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62(8):1556–1561.

- , , , , , . Perceptions of readmitted patients on the transition from hospital to home. J Hosp Med. 2012;7(9):709–712.

- , , , et al. Factors contributing to all‐cause 30‐day readmissions: a structured case series across 18 hospitals. Med Care. 2012;50(7):599–605.

- , , . Reasons for readmission in heart failure: perspectives of patients, caregivers, cardiologists, and heart failure nurses. Heart Lung. 2009;38(5):427–434.

- , , , et al. Patient‐identified factors related to heart failure readmissions. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2013;6(2):171–177.

- , , , , . Early readmission among patients with diabetes: a qualitative assessment of contributing factors. J Diabetes Complications. 2014;28(6):869–873.

- , , , , . “Because I was sick”: seriously ill veterans' perspectives on reason for 30‐day readmissions. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63(3):537–542.

- , , , et al. The impact of patient‐centered care on outcomes. J Fam Pract. 2000;49(9):796–804.

- , , , et al. Patient‐centered communication and diagnostic testing. Ann Fam Med. 2005;3(5):415–421.

- , . Physician communication and patient adherence to treatment: a meta‐analysis. Med Care. 2009;47(8):826–834.

- , , , et al. Closing the loop: physician communication with diabetic patients who have low health literacy. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(1):83–90.

- , , , , . Patients' participation in medical care: effects on blood sugar control and quality of life in diabetes. J Gen Intern Med. 1988;3(5):448–457.

- , , , , , . Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata‐driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377–381.

- , , . Public reporting of discharge planning and rates of readmissions. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(27):2637–2645.

- , , , et al. Quality of discharge practices and patient understanding at an academic medical center. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(18):1715–1722

- , , , , , . Understanding why patients of low socioeconomic status prefer hospitals over ambulatory care. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32(7):1196–1203.

- , . What will it take to move the needle on hospital readmissions? Am J Med Qual. 2013;29(4):357–359.

- , , , , , . Medicare readmission rates showed meaningful decline in 2012. Medicare Medicaid Res Rev. 2013;3(2):E1–E12.

- , , , , . Interventions to reduce 30‐day rehospitalization: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(8):520–528.

- , , , et al. Preventing 30‐day hospital readmissions: a systematic review and meta‐analysis of randomized trials. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(7):1095–1107.

- , , , et al. Relationship between early physician follow‐up and 30‐day readmission among Medicare beneficiaries hospitalized for heart failure. JAMA. 2010;303(17):1716–1722.

- , , , et al. Allocating scarce resources in real‐time to reduce heart failure readmissions: a prospective, controlled study. BMJ Qual Saf. 2013;22(12):998–1005.

- , , , , , . Readmissions in the era of patient engagement. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(11):1870–1872.

- , , , et al. Comparing perspectives of patients, caregivers, and clinicians on heart failure management [published online October 23, 2015]. J Card Fail. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2015.10.011.

- , , , . The care transitions intervention: results of a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(17):1822–1828.

- , , . Understanding rehospitalization risk: can hospital discharge be modified to reduce recurrent hospitalization? J Hosp Med. 2007;2(5):297–304.

- , , . Reasons for readmission in an underserved high‐risk population: a qualitative analysis of a series of inpatient interviews. BMJ Open. 2013;3(9):e003212.

- , , , , , . Improving care transitions: the patient perspective. J Health Commun. 2012;17(suppl 3):312–324.

- , , , et al. Challenges faced by patients with low socioeconomic status during the post‐hospital transition. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(2):283–289.

- , , , et al. “Missing pieces”—functional, social, and environmental barriers to recovery for vulnerable older adults transitioning from hospital to home. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62(8):1556–1561.

- , , , , , . Perceptions of readmitted patients on the transition from hospital to home. J Hosp Med. 2012;7(9):709–712.

- , , , et al. Factors contributing to all‐cause 30‐day readmissions: a structured case series across 18 hospitals. Med Care. 2012;50(7):599–605.

- , , . Reasons for readmission in heart failure: perspectives of patients, caregivers, cardiologists, and heart failure nurses. Heart Lung. 2009;38(5):427–434.

- , , , et al. Patient‐identified factors related to heart failure readmissions. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2013;6(2):171–177.

- , , , , . Early readmission among patients with diabetes: a qualitative assessment of contributing factors. J Diabetes Complications. 2014;28(6):869–873.

- , , , , . “Because I was sick”: seriously ill veterans' perspectives on reason for 30‐day readmissions. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63(3):537–542.

- , , , et al. The impact of patient‐centered care on outcomes. J Fam Pract. 2000;49(9):796–804.

- , , , et al. Patient‐centered communication and diagnostic testing. Ann Fam Med. 2005;3(5):415–421.

- , . Physician communication and patient adherence to treatment: a meta‐analysis. Med Care. 2009;47(8):826–834.

- , , , et al. Closing the loop: physician communication with diabetic patients who have low health literacy. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(1):83–90.

- , , , , . Patients' participation in medical care: effects on blood sugar control and quality of life in diabetes. J Gen Intern Med. 1988;3(5):448–457.

- , , , , , . Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata‐driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377–381.

- , , . Public reporting of discharge planning and rates of readmissions. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(27):2637–2645.

- , , , et al. Quality of discharge practices and patient understanding at an academic medical center. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(18):1715–1722

- , , , , , . Understanding why patients of low socioeconomic status prefer hospitals over ambulatory care. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32(7):1196–1203.

© 2016 Society of Hospital Medicine

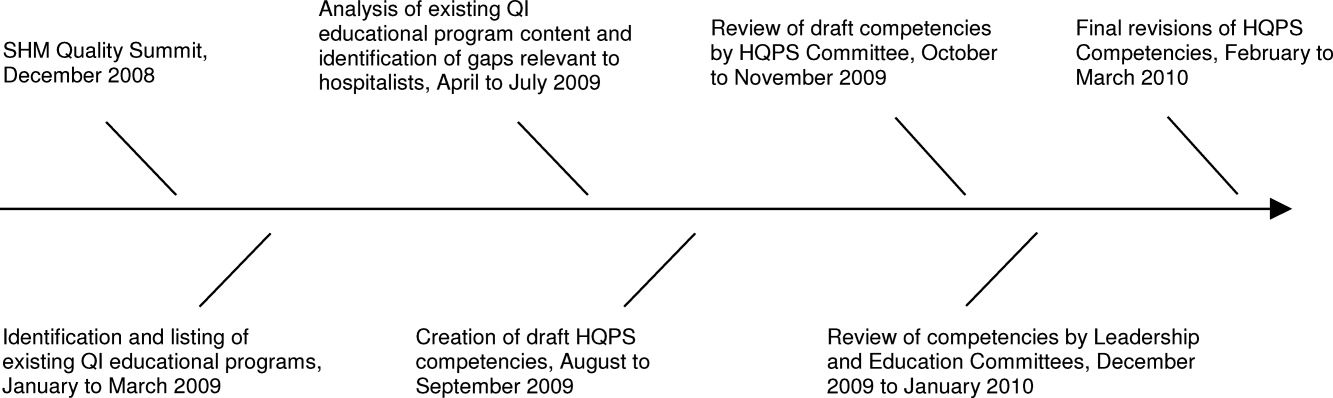

HQPS Competencies

Healthcare quality is defined as the degree to which health services for individuals and populations increase the likelihood of desired health outcomes and are consistent with current professional knowledge.1 Delivering high quality care to patients in the hospital setting is especially challenging, given the rapid pace of clinical care, the severity and multitude of patient conditions, and the interdependence of complex processes within the hospital system. Research has shown that hospitalized patients do not consistently receive recommended care2 and are at risk for experiencing preventable harm.3 In an effort to stimulate improvement, stakeholders have called for increased accountability, including enhanced transparency and differential payment based on performance. A growing number of hospital process and outcome measures are readily available to the public via the Internet.46 The Joint Commission, which accredits US hospitals, requires the collection of core quality measure data7 and sets the expectation that National Patient Safety Goals be met to maintain accreditation.8 Moreover, the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) has developed a Value‐Based Purchasing (VBP) plan intended to adjust hospital payment based on quality measures and the occurrence of certain hospital‐acquired conditions.9, 10

Because of their clinical expertise, understanding of hospital clinical operations, leadership of multidisciplinary inpatient teams, and vested interest to improve the systems in which they work, hospitalists are perfectly positioned to collaborate with their institutions to improve the quality of care delivered to inpatients. However, many hospitalists are inadequately prepared to engage in efforts to improve quality, because medical schools and residency programs have not traditionally included or emphasized healthcare quality and patient safety in their curricula.1113 In a survey of 389 internal medicine‐trained hospitalists, significant educational deficiencies were identified in the area of systems‐based practice.14 Specifically, the topics of quality improvement, team management, practice guideline development, health information systems management, and coordination of care between healthcare settings were listed as essential skills for hospitalist practice but underemphasized in residency training. Recognizing the gap between the needs of practicing physicians and current medical education provided in healthcare quality, professional societies have recently published position papers calling for increased training in quality, safety, and systems, both in medical school11 and residency training.15, 16