User login

U.S. Physician Satisfaction

The burden of dissatisfaction among medical professionals concerns both physicians and policy makers, especially given the potential ramifications on the work force.1, 2 Abundant research documents a strong relationship between low levels of physician satisfaction and burnout,37 intention to leave,6, 815 and job turnover.13, 1618 Moreover, low physician satisfaction is associated with self‐reported psychiatric symptoms1921 and poorer perceived mental health.22 Not surprisingly, dissatisfied physicians are less likely to recommend to medical students that they pursue their specialty.23

Importantly, physician satisfaction appears to benefit patients. Several studies show a positive relationship between higher physician satisfaction and patient satisfaction and outcomes.2426 Patients cared for by satisfied physicians declare more trust and confidence in their physicians, have better continuity, higher ratings of their care,26, 27 lower no‐show rates,25 and enhanced adherence to their medical care.28 There is also some evidence that higher job satisfaction is associated with lower likelihood of patient errors and suboptimal patient care.29

Physician satisfaction can be influenced by factors intrinsic to the individual physician (age, gender, race, and specialty) and extrinsic to the physician (work environment, practice setting, patient characteristics, and income).22, 30 In this way, satisfaction is not a static property in any physician or physician group, but reflects a dynamic interplay among the expectations and environments within which they work. Although each physician, physician group, and specialty has distinct factors that affect satisfaction, none are immune to potential dissatisfaction.

Given the documented impact of physician satisfaction on multiple aspects of healthcare delivery, we undertook a systematic review of the existing literature to achieve a greater understanding of the current state of U.S. physician satisfaction. In addition, we sought to identify the major survey tools used to measure satisfaction and the characteristics intrinsic and extrinsic to the physician that are associated with satisfaction. We conclude by suggesting needed additional research.

Materials and Methods

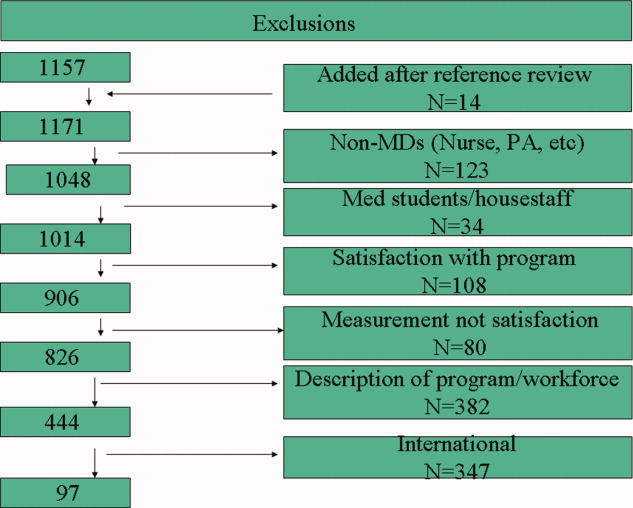

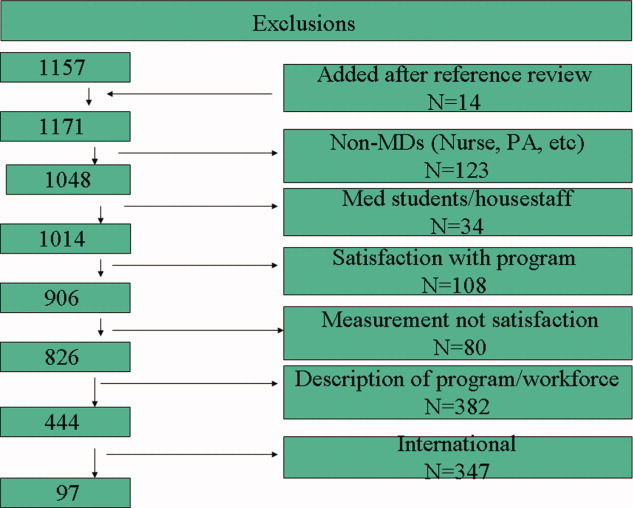

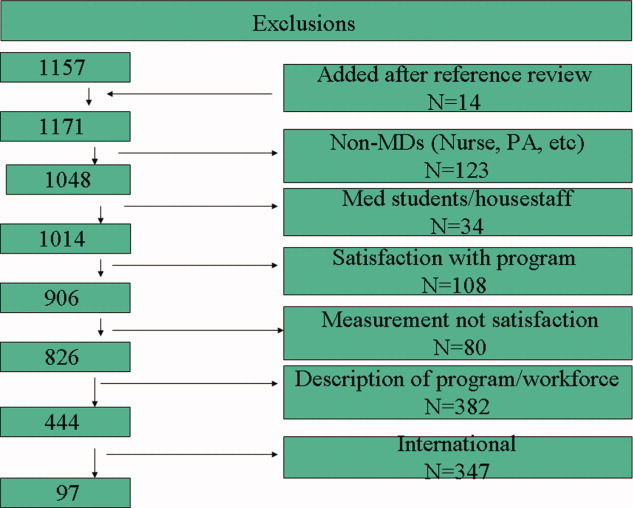

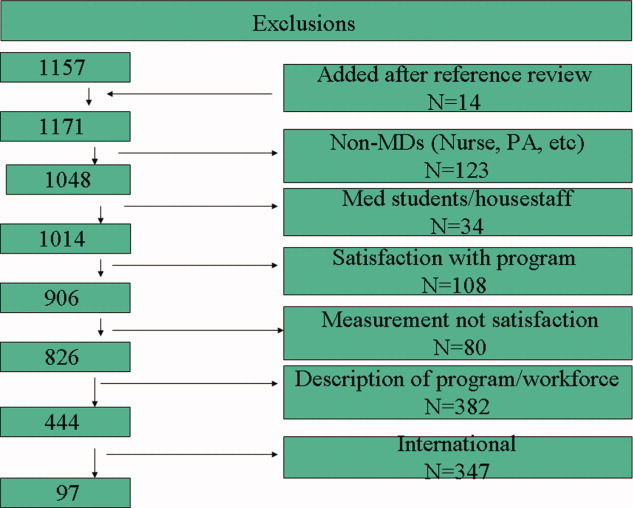

We performed a literature search of MEDLINE (

Results

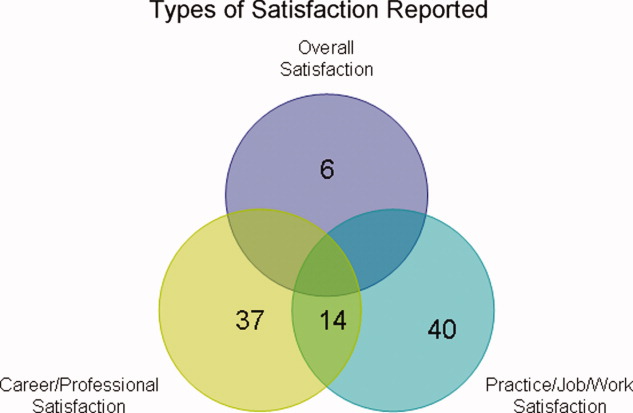

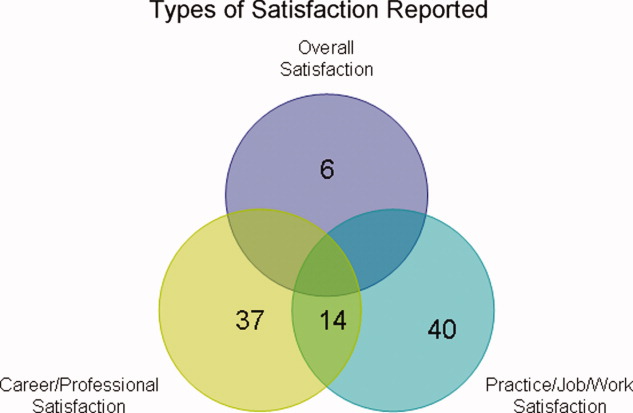

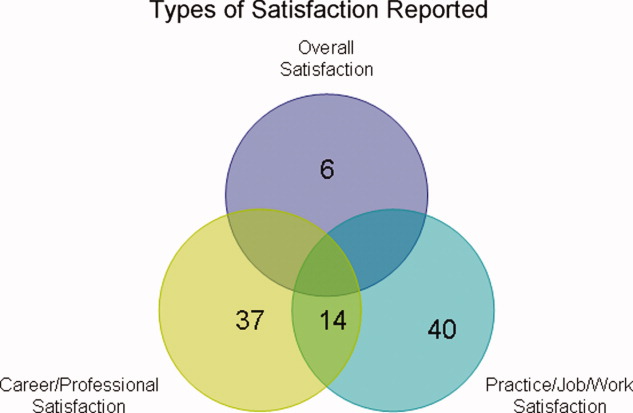

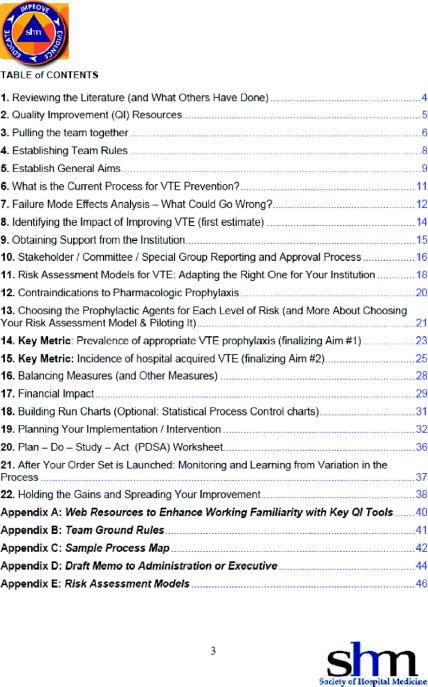

Of the 97 studies, 69 were cross‐sectional (distributed to purposive and often convenience samples of physicians) with sampling sizes ranging from 39 to 6441 and response rates ranging from 31% to 97% (Appendix 1). The other 28 were from larger nationally representative studies (Table 1), including the CTS (n = 92, 45, 71, 74, 91, 102, 104106), RWJS (n = 81, 18, 3334, 39, 40, 60, 61), PWS (n = 711, 22, 23, 55, 83, 92, 99), and WPHS (n = 444, 4951). Fourteen articles reported information from longitudinal (n = 2)18, 86 or repeated cross‐sectional studies (n = 12)1, 2, 39, 73, 76, 79, 85, 91, 96, 97, 102, 110 to help determine satisfaction trends. The survey instruments from the 4 national physician surveys are outlined in Table 1. The types of satisfaction reported are outlined in Figure 2.

| Survey | Satisfaction Measured | MD Type Sampled | Sampled/Responded/Adjusted Response [n/n/% (year of survey)] |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| PWS | 150‐item survey; 3 satisfaction domains (job, career, and specialty; all 5‐point Likert scales); 10 satisfaction facets | AMA Masterfile; random sample; FP, IM, IM specialists, pediatrics, and pediatric specialists | 5704/2326/52% |

| CTS | Career satisfaction (5 point Likert scale) | AMA Masterfile; random sample; all physicians in direct patient care 20+ hours a week | 19054/12385/65% (1996); 20131/12280/61% (1998); 20998/12389/59% (2000) |

| RWJ | Practice satisfaction (4‐point Likert scale); career satisfaction (3‐point Likert scale) | AMA Masterfile; random sample; 1987: physicians <40 years old in practice 1‐6 years; 1991: physicians <45 years old in practice 2‐9 years; 1997: physicians <52 years old in practice 8‐17 years | 8379/5865/70% (1987); 9745/4373/70% (1991); 2093/1549/74% (1997) |

| WPHS | Career satisfaction (5‐point Likert scale) | AMA Masterfile; random sample; female medical school graduates from 1950 to 1989 | 4501/2656/59% |

Trends in U.S. Physician Satisfaction

The CTS physician survey used sophisticated large‐scale random sampling methods and consistent questionnaires, thus allowing assessment of trends. From these repeated cross‐sectional surveys, career satisfaction from 1996 to 2001 was stable (81% to 80% among primary care physicians [PCPs], and 81% to 81% among specialists), although the portion of PCPs who report being very satisfied declined from 42% to 38% (P < 0.001) with no significant change for specialists (43% to 42%; P = 0.20).2

The RWJ surveys found small overall declines. From 1991 to 1997, practice satisfaction declined from 86% to 79%, and career satisfaction declined 96% to 88% (P = not available [NA]).1 A comparison of the 1991 RWJ survey to a 1996 age‐matched California physician survey and also found practice satisfaction declined slightly (86% to 82%, P = NA; very satisfied declined 48% to 37%, P = 0.05).39

Two studies of PCPs in Massachusetts found similar modest declines. The first found practice satisfaction declined from 80% to 66% (1996 to 1999; P < 0.001),73 and the second found a nonsignificant decline in professional satisfaction from 81% to 73% (1986 to 1997; P = not significant [NS]).85 Other studies of specific physician populations found insignificant changes in satisfaction levels during the study periods.76, 79, 86, 91, 96, 97, 110 In summary, recent overall physician satisfaction is relatively unchanged, although there may be modest declines in PCPs and young physicians who report high satisfaction, as evidenced from the CTS, RWJ studies, and other small physician cohorts.

Major Characteristics Associated with Physician Satisfaction

Both factors intrinsic to the physician and characteristics of the job influence physician satisfaction (Figure 3). Intrinsic physician factors are typically not changeable when developing strategies to improve satisfaction. However, they do significantly affect what physicians consider important when choosing a job, and influence how physicians respond to changes in the job. Job characteristics, or extrinsic factors, are generally considered more modifiable when developing institutional strategies to improve satisfaction. Although the intrinsic factors are seemingly unmodifiable, one must take them into account when assessing satisfaction in order to determine the independent effects that the more modifiable extrinsic factors have on satisfaction. The next section describes the variables associated with satisfaction, from the 37 studies that utilized multivariate analyses (Appendix 2) to control for other factors (Appendix 3).

Physician Factors

Physician Age

Age is likely weakly but independently associated with satisfaction, although interpretation is limited by the heterogeneity of the physician samples and the manner in which age is reported. Of the 18 studies that evaluated age, 3 (from the PWS, WPHS, and 1 other) found a weak but positive association.9, 23, 50 Five (from the CTS and others) found a U‐shaped relationship (those at the extremes of age were the most satisfied),59, 68, 70, 71, 74 and 3 found an inverse association (2 CTS PCP subsets, and 1 small single‐county study.35, 45, 106 Six found no association, of which only 1 was from a nationally representative sample (PWS PCPs).5, 96, 97, 109, 110, 112

As a surrogate for age, 6 studies evaluated years in practice or years since medical school graduation. Of these, 2 found a weak but positive association (although only seen in specialists, not PCPs in the CTS),89, 104 and 1 found a negative association (when dichotomized),73 with no association in 3 smaller studies.5, 56, 88

These studies support that age is weakly but independently associated with physician satisfaction when studied as a continuous variable. When studied within various age brackets, studies support a U‐shaped association, with the highest satisfaction in those at the extremes of ages, although this may not be true for PCPs. In addition, the association with older age may be the result of less satisfied physicians leaving the profession.

Physician Gender

The association between gender and overall satisfaction is difficult to interpret due to the heterogeneity of the satisfaction assessments and included confounders, although there may be gender differences in facets of satisfaction. Of the 22 studies that evaluated gender, 3 found an independent effect for women (PWS general internal medicine [GIM] sample, CTS, and 1 other),23, 104, 110 3 for men,41, 81, 98 and no gender effect in the others. Those that found men with higher satisfaction included 1 national study of family practitioners (FPs)98 and 2 academic studies, the latter of which found men with or without children with higher satisfaction compared to women with children, indicating children (or work life balance) may confound gender satisfaction.41, 81

Other national studies, including the CTS and PWS, did not find a gender difference in overall satisfaction,9, 35, 45, 56, 59, 68, 71, 73, 74, 88, 89, 96, 97, 106, 109 although the PWS did find differences in facets of satisfaction (women were more satisfied with relationships with colleagues and patients, but less satisfied with autonomy, pay, resources, and community relationships).83

In summary, the relationship between gender and overall satisfaction is likely confounded by many factors, and its independent effect is difficult to quantify given the heterogeneity of the studies reviewed. There may be gender differences in facets of satisfaction, evaluated only in the PWS.

Physician Race/Ethnicity

There were only 5 multivariate studies delineating the association of race/ethnicity with satisfaction, of which 4 found no difference.35, 50, 56, 88 One study found lower satisfaction in minorities compared to whites, but was only a small sample of preventive medicine physicians.93 Given the growing racial and ethnic diversity of physicians, future research should further explore this association.

Physician Specialty

Overall, pediatricians appear to have higher, and GIM to have lower, satisfaction when compared among the PCPs or specialists, although the interpretation is limited by the heterogeneity of the specialties included, how the specialties are demarcated, and the composition of the reference group.

Of the 17 studies that evaluated specialty, 6 found pediatricians had higher satisfaction (including the CTS),5, 70, 73, 74, 104, 106 and 5 found GIM to have lower satisfaction (including the CTS and PWS)5, 11, 74, 104, 106 than various other comparison groups. Generalized interpretation of the other studies is difficult, as 8 of the 11 arise from very specific convenience samples of physicians (within a state or county).35, 56, 68, 73, 89, 96, 97, 109

Job Factors

Job Demand

There is evidence of a relationship between subjective, but not objective, job demands and satisfaction (categorized in the literature as work stress/pressure, workload, and work hours). Of the 10 studies that evaluated various types of perceived work stress/pressure, 9 found a significant association with dissatisfaction.5, 11, 22, 23, 45, 50, 68, 98, 104

Of the 8 studies that evaluated workload, 4 of them evaluated subjective workload and found too much or too little was associated with dissatisfaction.50, 86, 107, 110 The other 4 evaluated actual number of visits (per week or per hour); 3 did not find an association5, 56, 68 and 1 found a weak but negative association with satisfaction.70

Of the 13 studies that evaluated work hours, 8 found no association (including the PWS, CTS, and WPHS).23, 50, 73, 88, 89, 104, 107, 112 Only 1 found a positive association; however, these results were from a stepwise regression analysis in which work stress had already been controlled for in the model, and a separate stepwise regression showed more work hours to be associated with higher stress levels.98 One found satisfaction with work hours had a strong association with overall satisfaction (but not actual work hours).86 Three found a weak negative association, the last of which found that a recent increase in work hours was significantly associated with dissatisfaction, but not actual work hours.2, 70, 84

Of the 3 studies that evaluated on‐call frequency, 2 found higher call frequency to be moderately negatively associated70, 88 and 1 found no association.50

In summary, there is unequivocal evidence that an imbalance between expected and experienced stress, pressure, or workload is moderately associated with dissatisfaction, but there is less evidence of a significant association with objective workload or work hours. On‐call duty may moderately negatively influence satisfaction, although based only on 2 small studies.

Job Control/Autonomy

There is also a strong association with satisfaction and physician control over elements in their work place. Although the studies are heterogeneous in their assessment of work control and autonomy, 15 of the 16 studies found these dimensions to be strongly and significantly associated with satisfaction.1, 2, 5, 20, 45, 50, 56, 68, 71, 86, 96, 97, 104, 107, 109, 112

Relationship with Colleagues

All 5 studies associating relationship with colleagues with satisfaction found the perception of collegial support/emnteraction to exert a moderate independent effect on satisfaction.5, 20, 89, 104, 112

Part‐time Work Status

Of the 3 studies that evaluated this factor in multivariate analysis, 2 did not find a significant association,71, 110 and 1 reported higher satisfaction with full time work (but did not report statistical values).9 Given the number of U.S. physicians working part time, this warrants further research.

Practice Characteristics (Size/Setting/Site/Ownership)

The interpretation of practice characteristics and satisfaction is limited by the heterogeneity in the way the studies partitioned the practice characteristics, and the reference group composition. Of the 10 studies that evaluated several types of practice settings, 5 found solo or small (1‐2 person) practice sizes more likely associated with dissatisfaction than larger practice sizes.88, 97, 104106 The PWS and CTS obstetrician‐gynecologist (ob‐gyn) subset also found health maintenance organization (HMO) satisfaction to be lower compared to various comparisons11, 71 (although the PWS GIM subset did not find a difference).23 Of the 6 surveys evaluating academic/medical school as the reference group, 4 found higher satisfaction with academics (including 2 from the CTS),9, 71, 104, 110 but 2 smaller studies did not find a difference with university affiliation or teaching.88, 96 Of those studies evaluating single vs. multispecialty groups, only 1 found single‐specialty with higher satisfaction than multispecialty89 and 3 others did not find a difference.56, 68, 73

Regarding practice size, 3 of the 4 found no association with satisfaction.56, 109, 110, 112 Only the CTS evaluated practice region and community size and found rural physicians, those in small metropolitan areas, and those in New England and West North central regions had higher satisfaction.45, 71, 74 The CTS also supports that physicians that are part‐owners or nonowners of their practice have higher satisfaction than full owners.45, 74

In summary, practice characteristics may influence physician satisfaction. Physicians in solo and HMO practices may be less satisfied than physicians in other practice settings and sizes, and academic affiliation may have a small but significant association with satisfaction. Practice size and single vs. multispecialty does not appear to significantly affect satisfaction, and satisfaction association with practice region, community size, and ownership is drawn primarily from the CTS and requires further study.

Patient‐payer Mix and Insurance Status

Capitation and provider‐managed care training does appear to affect satisfaction, but managed care or patient insurance status does not. Of the 9 studies that addressed the influence of managed care or capitation on satisfaction, the percentage of managed care practice revenue, number of managed care contracts, or percentage of managed care patients in a practice had no association with satisfaction.2, 71, 73, 74, 104, 105, 109, 112 Two studies did find that capitation was associated with provider dissatisfaction.2, 68 One CTS study found career satisfaction increased in states after the implementation of patient protection acts (implying physician satisfaction increased with less managed care control and more patient/provider empowerment).102 Two other studies found that physicians with training in managed care and positive attitudes about managed care were more likely to be satisfied.98, 112

Regarding insurance status, 3 studies of PCPs in different states did not find an association between satisfaction and insurance (private, none, Medicare, or Medicaid),35, 68, 89 although a study of rural PCPs found more dissatisfaction in those who reported a recent decrease in the number of patients with adequate insurance.84

In summary, there is unlikely an independent effect of patient‐payer mix or managed care on satisfaction. However, capitation may exert a negative effect, and managed care training (and attitude) may exert a positive effect.

Patient Characteristics

Most patient factors were not found to be independently associated with physician satisfaction, including patient complexity,23, 112 patient demands,5, 20 or specific patient demographics.56 The PWS and CTS studies found physicians who value and are able to maintain long‐term patient relationships were more satisfied.45, 104, 112 One study found that those who perceive patients lack confidence in physicians were more likely to be dissatisfied.109 In summary, patient characteristics do not appear to influence provider satisfaction, but a provider's value of, and ability to maintain, long‐term relationships, as well as their perception of patient trust, may influence satisfaction.

Income

Of the 14 studies that evaluated income, 11 found a positive association (the CTS, RWJ, and others) with actual income1, 2, 45, 74, 84, 88, 93, 104 and income satisfaction.97, 98, 109 Of the 3 that did not find an association with actual income, 2 were from the PWS,23, 112 and 1 from the CTS ob‐gyn subset.71

In summary, the association between actual income and satisfaction may be confounded by other variables (such as work hours and part‐time status), but satisfaction with income does appear to correlate with overall satisfaction.

Incentives

There does appear to be a moderate satisfaction association with the types of income incentives. The CTS studies found more satisfied physicians were those with the ability to make clinical decisions without affecting one's income (although that was not found for the PCP subset).45, 104, 106 Other studies found more satisfaction in those reporting a practice with incentives/emphasis based on quality, and less satisfaction in those with incentives/emphasis based on productivity or service reduction.1, 57, 112 Therefore, the evidence favors higher satisfaction with incentives based on quality rather than productivity or utilization.

Other Physician Factors

Board certification may be modestly positively associated with satisfaction, and being a foreign medical graduate may be modestly negatively associated with satisfaction, although this is limited to few studies.9, 45, 74, 98, 104, 106 Other physician characteristics, such as personal matters (marital status, home stress, mental health, personal satisfaction), work matters (amount of charity care they provide and history of work harassment), and personality (reform mindedness and tolerance for uncertainty) require further research.50, 56, 88, 98, 104

Discussion

Our review of satisfaction trends for U.S. physicians revealed relative stability except for a slight decline among PCPs. We found factors significantly associated with satisfaction to include both physician (age and specialty) and job factors (work demand, work control, colleague support, ability to maintain patient relationships, practice setting, income satisfaction, and incentive types). Based on limited data, the association with race/ethnicity and part‐time work requires more research, and factors that do not appear to have an independent effect on satisfaction include physician gender, patient‐payer mix, and patient characteristics.

As the fastest growing specialty in the history of American medicine, hospital medicine should focus on career satisfaction as a top priority in shaping the future of the more than 20,000 hospitalists now practicing. Although the term hospitalist was coined less than 15 years ago114 the demand for hospitalists is expected to grow to as many as 50,000 by 2020.115 In this time of rapid growth, in order to mold a sustainable specialty, we must all recognize the factors that contribute to satisfaction and strive to maintain good job‐person fit. For individual hospitalists, all of these mediators of satisfaction should be considered when contemplating employment. To ensure a mutual fit, each physician must reflect on how their goals and values coincide with those of the program they are considering. For hospital medicine program leaders, areas of program‐specific dissatisfaction must be continually sought and addressed.

In this review, the variables with the strongest associations with satisfaction that are most pertinent to hospitalists are work demand, control, income/emncentives, and collegial relationships. These variables coincide with the 4 pillars of career satisfaction identified in the Society of Hospital Medicine Career Satisfaction Task Force.116 Perceived work stress/pressure and objective workload can easily (and serially) be measured, and the latter can be compared to national benchmarks to ensure appropriate workload expectations.116 Reducing work pressure/stress may involve assessing and matching variations in workload with manpower, reducing nonclinical tasks by utilizing administrative assistants or physician extenders, or having an emergency plan for unexpected absences. Autonomy and control can be assessed by the job‐fit questionnaire to identify programwide and physician‐specific areas of potential discontent.116 Increasing autonomy/control may involve pursuing leadership within hospital projects or committees, creatively scheduling flexibility, and seeking support from hospital administration. Income expectations should also be couched within national benchmarks, and incentive programs should reflect work quality rather than quantity. Collegial support can be enhanced by instituting a mentoring program, journal club, regular social function, or configuration of offices spaces to allow proximity. Although the conclusions of this review are limited by the lack of hospitalists included in the studies and our inability to perform a meta‐analysis, we believe extrapolation of this information to hospitalist physicians is valid and appropriate. That said, future studies specifically addressing hospitalist satisfaction are needed to ensure this.

Conclusions

In summary, physician satisfaction is not a static parameter, but a dynamic entity mediated by both physician‐related and job‐related factors, the majority of which are modifiable. Thus hospitalists and hospital medicine program leaders can be optimistic that uncovering the presence of dissatisfaction through surveys, and addressing the issues triggering it, should enhance physician satisfaction. With improved awareness of mitigating factors of dissatisfaction and commitments to improvement, there is reason for hope. It is unreasonable to believe that dissatisfaction is intrinsic to any medical profession. It is reasonable to believe that physician satisfaction, with all of its desirable implications, can be attained through continual research and prioritization.

The burden of dissatisfaction among medical professionals concerns both physicians and policy makers, especially given the potential ramifications on the work force.1, 2 Abundant research documents a strong relationship between low levels of physician satisfaction and burnout,37 intention to leave,6, 815 and job turnover.13, 1618 Moreover, low physician satisfaction is associated with self‐reported psychiatric symptoms1921 and poorer perceived mental health.22 Not surprisingly, dissatisfied physicians are less likely to recommend to medical students that they pursue their specialty.23

Importantly, physician satisfaction appears to benefit patients. Several studies show a positive relationship between higher physician satisfaction and patient satisfaction and outcomes.2426 Patients cared for by satisfied physicians declare more trust and confidence in their physicians, have better continuity, higher ratings of their care,26, 27 lower no‐show rates,25 and enhanced adherence to their medical care.28 There is also some evidence that higher job satisfaction is associated with lower likelihood of patient errors and suboptimal patient care.29

Physician satisfaction can be influenced by factors intrinsic to the individual physician (age, gender, race, and specialty) and extrinsic to the physician (work environment, practice setting, patient characteristics, and income).22, 30 In this way, satisfaction is not a static property in any physician or physician group, but reflects a dynamic interplay among the expectations and environments within which they work. Although each physician, physician group, and specialty has distinct factors that affect satisfaction, none are immune to potential dissatisfaction.

Given the documented impact of physician satisfaction on multiple aspects of healthcare delivery, we undertook a systematic review of the existing literature to achieve a greater understanding of the current state of U.S. physician satisfaction. In addition, we sought to identify the major survey tools used to measure satisfaction and the characteristics intrinsic and extrinsic to the physician that are associated with satisfaction. We conclude by suggesting needed additional research.

Materials and Methods

We performed a literature search of MEDLINE (

Results

Of the 97 studies, 69 were cross‐sectional (distributed to purposive and often convenience samples of physicians) with sampling sizes ranging from 39 to 6441 and response rates ranging from 31% to 97% (Appendix 1). The other 28 were from larger nationally representative studies (Table 1), including the CTS (n = 92, 45, 71, 74, 91, 102, 104106), RWJS (n = 81, 18, 3334, 39, 40, 60, 61), PWS (n = 711, 22, 23, 55, 83, 92, 99), and WPHS (n = 444, 4951). Fourteen articles reported information from longitudinal (n = 2)18, 86 or repeated cross‐sectional studies (n = 12)1, 2, 39, 73, 76, 79, 85, 91, 96, 97, 102, 110 to help determine satisfaction trends. The survey instruments from the 4 national physician surveys are outlined in Table 1. The types of satisfaction reported are outlined in Figure 2.

| Survey | Satisfaction Measured | MD Type Sampled | Sampled/Responded/Adjusted Response [n/n/% (year of survey)] |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| PWS | 150‐item survey; 3 satisfaction domains (job, career, and specialty; all 5‐point Likert scales); 10 satisfaction facets | AMA Masterfile; random sample; FP, IM, IM specialists, pediatrics, and pediatric specialists | 5704/2326/52% |

| CTS | Career satisfaction (5 point Likert scale) | AMA Masterfile; random sample; all physicians in direct patient care 20+ hours a week | 19054/12385/65% (1996); 20131/12280/61% (1998); 20998/12389/59% (2000) |

| RWJ | Practice satisfaction (4‐point Likert scale); career satisfaction (3‐point Likert scale) | AMA Masterfile; random sample; 1987: physicians <40 years old in practice 1‐6 years; 1991: physicians <45 years old in practice 2‐9 years; 1997: physicians <52 years old in practice 8‐17 years | 8379/5865/70% (1987); 9745/4373/70% (1991); 2093/1549/74% (1997) |

| WPHS | Career satisfaction (5‐point Likert scale) | AMA Masterfile; random sample; female medical school graduates from 1950 to 1989 | 4501/2656/59% |

Trends in U.S. Physician Satisfaction

The CTS physician survey used sophisticated large‐scale random sampling methods and consistent questionnaires, thus allowing assessment of trends. From these repeated cross‐sectional surveys, career satisfaction from 1996 to 2001 was stable (81% to 80% among primary care physicians [PCPs], and 81% to 81% among specialists), although the portion of PCPs who report being very satisfied declined from 42% to 38% (P < 0.001) with no significant change for specialists (43% to 42%; P = 0.20).2

The RWJ surveys found small overall declines. From 1991 to 1997, practice satisfaction declined from 86% to 79%, and career satisfaction declined 96% to 88% (P = not available [NA]).1 A comparison of the 1991 RWJ survey to a 1996 age‐matched California physician survey and also found practice satisfaction declined slightly (86% to 82%, P = NA; very satisfied declined 48% to 37%, P = 0.05).39

Two studies of PCPs in Massachusetts found similar modest declines. The first found practice satisfaction declined from 80% to 66% (1996 to 1999; P < 0.001),73 and the second found a nonsignificant decline in professional satisfaction from 81% to 73% (1986 to 1997; P = not significant [NS]).85 Other studies of specific physician populations found insignificant changes in satisfaction levels during the study periods.76, 79, 86, 91, 96, 97, 110 In summary, recent overall physician satisfaction is relatively unchanged, although there may be modest declines in PCPs and young physicians who report high satisfaction, as evidenced from the CTS, RWJ studies, and other small physician cohorts.

Major Characteristics Associated with Physician Satisfaction

Both factors intrinsic to the physician and characteristics of the job influence physician satisfaction (Figure 3). Intrinsic physician factors are typically not changeable when developing strategies to improve satisfaction. However, they do significantly affect what physicians consider important when choosing a job, and influence how physicians respond to changes in the job. Job characteristics, or extrinsic factors, are generally considered more modifiable when developing institutional strategies to improve satisfaction. Although the intrinsic factors are seemingly unmodifiable, one must take them into account when assessing satisfaction in order to determine the independent effects that the more modifiable extrinsic factors have on satisfaction. The next section describes the variables associated with satisfaction, from the 37 studies that utilized multivariate analyses (Appendix 2) to control for other factors (Appendix 3).

Physician Factors

Physician Age

Age is likely weakly but independently associated with satisfaction, although interpretation is limited by the heterogeneity of the physician samples and the manner in which age is reported. Of the 18 studies that evaluated age, 3 (from the PWS, WPHS, and 1 other) found a weak but positive association.9, 23, 50 Five (from the CTS and others) found a U‐shaped relationship (those at the extremes of age were the most satisfied),59, 68, 70, 71, 74 and 3 found an inverse association (2 CTS PCP subsets, and 1 small single‐county study.35, 45, 106 Six found no association, of which only 1 was from a nationally representative sample (PWS PCPs).5, 96, 97, 109, 110, 112

As a surrogate for age, 6 studies evaluated years in practice or years since medical school graduation. Of these, 2 found a weak but positive association (although only seen in specialists, not PCPs in the CTS),89, 104 and 1 found a negative association (when dichotomized),73 with no association in 3 smaller studies.5, 56, 88

These studies support that age is weakly but independently associated with physician satisfaction when studied as a continuous variable. When studied within various age brackets, studies support a U‐shaped association, with the highest satisfaction in those at the extremes of ages, although this may not be true for PCPs. In addition, the association with older age may be the result of less satisfied physicians leaving the profession.

Physician Gender

The association between gender and overall satisfaction is difficult to interpret due to the heterogeneity of the satisfaction assessments and included confounders, although there may be gender differences in facets of satisfaction. Of the 22 studies that evaluated gender, 3 found an independent effect for women (PWS general internal medicine [GIM] sample, CTS, and 1 other),23, 104, 110 3 for men,41, 81, 98 and no gender effect in the others. Those that found men with higher satisfaction included 1 national study of family practitioners (FPs)98 and 2 academic studies, the latter of which found men with or without children with higher satisfaction compared to women with children, indicating children (or work life balance) may confound gender satisfaction.41, 81

Other national studies, including the CTS and PWS, did not find a gender difference in overall satisfaction,9, 35, 45, 56, 59, 68, 71, 73, 74, 88, 89, 96, 97, 106, 109 although the PWS did find differences in facets of satisfaction (women were more satisfied with relationships with colleagues and patients, but less satisfied with autonomy, pay, resources, and community relationships).83

In summary, the relationship between gender and overall satisfaction is likely confounded by many factors, and its independent effect is difficult to quantify given the heterogeneity of the studies reviewed. There may be gender differences in facets of satisfaction, evaluated only in the PWS.

Physician Race/Ethnicity

There were only 5 multivariate studies delineating the association of race/ethnicity with satisfaction, of which 4 found no difference.35, 50, 56, 88 One study found lower satisfaction in minorities compared to whites, but was only a small sample of preventive medicine physicians.93 Given the growing racial and ethnic diversity of physicians, future research should further explore this association.

Physician Specialty

Overall, pediatricians appear to have higher, and GIM to have lower, satisfaction when compared among the PCPs or specialists, although the interpretation is limited by the heterogeneity of the specialties included, how the specialties are demarcated, and the composition of the reference group.

Of the 17 studies that evaluated specialty, 6 found pediatricians had higher satisfaction (including the CTS),5, 70, 73, 74, 104, 106 and 5 found GIM to have lower satisfaction (including the CTS and PWS)5, 11, 74, 104, 106 than various other comparison groups. Generalized interpretation of the other studies is difficult, as 8 of the 11 arise from very specific convenience samples of physicians (within a state or county).35, 56, 68, 73, 89, 96, 97, 109

Job Factors

Job Demand

There is evidence of a relationship between subjective, but not objective, job demands and satisfaction (categorized in the literature as work stress/pressure, workload, and work hours). Of the 10 studies that evaluated various types of perceived work stress/pressure, 9 found a significant association with dissatisfaction.5, 11, 22, 23, 45, 50, 68, 98, 104

Of the 8 studies that evaluated workload, 4 of them evaluated subjective workload and found too much or too little was associated with dissatisfaction.50, 86, 107, 110 The other 4 evaluated actual number of visits (per week or per hour); 3 did not find an association5, 56, 68 and 1 found a weak but negative association with satisfaction.70

Of the 13 studies that evaluated work hours, 8 found no association (including the PWS, CTS, and WPHS).23, 50, 73, 88, 89, 104, 107, 112 Only 1 found a positive association; however, these results were from a stepwise regression analysis in which work stress had already been controlled for in the model, and a separate stepwise regression showed more work hours to be associated with higher stress levels.98 One found satisfaction with work hours had a strong association with overall satisfaction (but not actual work hours).86 Three found a weak negative association, the last of which found that a recent increase in work hours was significantly associated with dissatisfaction, but not actual work hours.2, 70, 84

Of the 3 studies that evaluated on‐call frequency, 2 found higher call frequency to be moderately negatively associated70, 88 and 1 found no association.50

In summary, there is unequivocal evidence that an imbalance between expected and experienced stress, pressure, or workload is moderately associated with dissatisfaction, but there is less evidence of a significant association with objective workload or work hours. On‐call duty may moderately negatively influence satisfaction, although based only on 2 small studies.

Job Control/Autonomy

There is also a strong association with satisfaction and physician control over elements in their work place. Although the studies are heterogeneous in their assessment of work control and autonomy, 15 of the 16 studies found these dimensions to be strongly and significantly associated with satisfaction.1, 2, 5, 20, 45, 50, 56, 68, 71, 86, 96, 97, 104, 107, 109, 112

Relationship with Colleagues

All 5 studies associating relationship with colleagues with satisfaction found the perception of collegial support/emnteraction to exert a moderate independent effect on satisfaction.5, 20, 89, 104, 112

Part‐time Work Status

Of the 3 studies that evaluated this factor in multivariate analysis, 2 did not find a significant association,71, 110 and 1 reported higher satisfaction with full time work (but did not report statistical values).9 Given the number of U.S. physicians working part time, this warrants further research.

Practice Characteristics (Size/Setting/Site/Ownership)

The interpretation of practice characteristics and satisfaction is limited by the heterogeneity in the way the studies partitioned the practice characteristics, and the reference group composition. Of the 10 studies that evaluated several types of practice settings, 5 found solo or small (1‐2 person) practice sizes more likely associated with dissatisfaction than larger practice sizes.88, 97, 104106 The PWS and CTS obstetrician‐gynecologist (ob‐gyn) subset also found health maintenance organization (HMO) satisfaction to be lower compared to various comparisons11, 71 (although the PWS GIM subset did not find a difference).23 Of the 6 surveys evaluating academic/medical school as the reference group, 4 found higher satisfaction with academics (including 2 from the CTS),9, 71, 104, 110 but 2 smaller studies did not find a difference with university affiliation or teaching.88, 96 Of those studies evaluating single vs. multispecialty groups, only 1 found single‐specialty with higher satisfaction than multispecialty89 and 3 others did not find a difference.56, 68, 73

Regarding practice size, 3 of the 4 found no association with satisfaction.56, 109, 110, 112 Only the CTS evaluated practice region and community size and found rural physicians, those in small metropolitan areas, and those in New England and West North central regions had higher satisfaction.45, 71, 74 The CTS also supports that physicians that are part‐owners or nonowners of their practice have higher satisfaction than full owners.45, 74

In summary, practice characteristics may influence physician satisfaction. Physicians in solo and HMO practices may be less satisfied than physicians in other practice settings and sizes, and academic affiliation may have a small but significant association with satisfaction. Practice size and single vs. multispecialty does not appear to significantly affect satisfaction, and satisfaction association with practice region, community size, and ownership is drawn primarily from the CTS and requires further study.

Patient‐payer Mix and Insurance Status

Capitation and provider‐managed care training does appear to affect satisfaction, but managed care or patient insurance status does not. Of the 9 studies that addressed the influence of managed care or capitation on satisfaction, the percentage of managed care practice revenue, number of managed care contracts, or percentage of managed care patients in a practice had no association with satisfaction.2, 71, 73, 74, 104, 105, 109, 112 Two studies did find that capitation was associated with provider dissatisfaction.2, 68 One CTS study found career satisfaction increased in states after the implementation of patient protection acts (implying physician satisfaction increased with less managed care control and more patient/provider empowerment).102 Two other studies found that physicians with training in managed care and positive attitudes about managed care were more likely to be satisfied.98, 112

Regarding insurance status, 3 studies of PCPs in different states did not find an association between satisfaction and insurance (private, none, Medicare, or Medicaid),35, 68, 89 although a study of rural PCPs found more dissatisfaction in those who reported a recent decrease in the number of patients with adequate insurance.84

In summary, there is unlikely an independent effect of patient‐payer mix or managed care on satisfaction. However, capitation may exert a negative effect, and managed care training (and attitude) may exert a positive effect.

Patient Characteristics

Most patient factors were not found to be independently associated with physician satisfaction, including patient complexity,23, 112 patient demands,5, 20 or specific patient demographics.56 The PWS and CTS studies found physicians who value and are able to maintain long‐term patient relationships were more satisfied.45, 104, 112 One study found that those who perceive patients lack confidence in physicians were more likely to be dissatisfied.109 In summary, patient characteristics do not appear to influence provider satisfaction, but a provider's value of, and ability to maintain, long‐term relationships, as well as their perception of patient trust, may influence satisfaction.

Income

Of the 14 studies that evaluated income, 11 found a positive association (the CTS, RWJ, and others) with actual income1, 2, 45, 74, 84, 88, 93, 104 and income satisfaction.97, 98, 109 Of the 3 that did not find an association with actual income, 2 were from the PWS,23, 112 and 1 from the CTS ob‐gyn subset.71

In summary, the association between actual income and satisfaction may be confounded by other variables (such as work hours and part‐time status), but satisfaction with income does appear to correlate with overall satisfaction.

Incentives

There does appear to be a moderate satisfaction association with the types of income incentives. The CTS studies found more satisfied physicians were those with the ability to make clinical decisions without affecting one's income (although that was not found for the PCP subset).45, 104, 106 Other studies found more satisfaction in those reporting a practice with incentives/emphasis based on quality, and less satisfaction in those with incentives/emphasis based on productivity or service reduction.1, 57, 112 Therefore, the evidence favors higher satisfaction with incentives based on quality rather than productivity or utilization.

Other Physician Factors

Board certification may be modestly positively associated with satisfaction, and being a foreign medical graduate may be modestly negatively associated with satisfaction, although this is limited to few studies.9, 45, 74, 98, 104, 106 Other physician characteristics, such as personal matters (marital status, home stress, mental health, personal satisfaction), work matters (amount of charity care they provide and history of work harassment), and personality (reform mindedness and tolerance for uncertainty) require further research.50, 56, 88, 98, 104

Discussion

Our review of satisfaction trends for U.S. physicians revealed relative stability except for a slight decline among PCPs. We found factors significantly associated with satisfaction to include both physician (age and specialty) and job factors (work demand, work control, colleague support, ability to maintain patient relationships, practice setting, income satisfaction, and incentive types). Based on limited data, the association with race/ethnicity and part‐time work requires more research, and factors that do not appear to have an independent effect on satisfaction include physician gender, patient‐payer mix, and patient characteristics.

As the fastest growing specialty in the history of American medicine, hospital medicine should focus on career satisfaction as a top priority in shaping the future of the more than 20,000 hospitalists now practicing. Although the term hospitalist was coined less than 15 years ago114 the demand for hospitalists is expected to grow to as many as 50,000 by 2020.115 In this time of rapid growth, in order to mold a sustainable specialty, we must all recognize the factors that contribute to satisfaction and strive to maintain good job‐person fit. For individual hospitalists, all of these mediators of satisfaction should be considered when contemplating employment. To ensure a mutual fit, each physician must reflect on how their goals and values coincide with those of the program they are considering. For hospital medicine program leaders, areas of program‐specific dissatisfaction must be continually sought and addressed.

In this review, the variables with the strongest associations with satisfaction that are most pertinent to hospitalists are work demand, control, income/emncentives, and collegial relationships. These variables coincide with the 4 pillars of career satisfaction identified in the Society of Hospital Medicine Career Satisfaction Task Force.116 Perceived work stress/pressure and objective workload can easily (and serially) be measured, and the latter can be compared to national benchmarks to ensure appropriate workload expectations.116 Reducing work pressure/stress may involve assessing and matching variations in workload with manpower, reducing nonclinical tasks by utilizing administrative assistants or physician extenders, or having an emergency plan for unexpected absences. Autonomy and control can be assessed by the job‐fit questionnaire to identify programwide and physician‐specific areas of potential discontent.116 Increasing autonomy/control may involve pursuing leadership within hospital projects or committees, creatively scheduling flexibility, and seeking support from hospital administration. Income expectations should also be couched within national benchmarks, and incentive programs should reflect work quality rather than quantity. Collegial support can be enhanced by instituting a mentoring program, journal club, regular social function, or configuration of offices spaces to allow proximity. Although the conclusions of this review are limited by the lack of hospitalists included in the studies and our inability to perform a meta‐analysis, we believe extrapolation of this information to hospitalist physicians is valid and appropriate. That said, future studies specifically addressing hospitalist satisfaction are needed to ensure this.

Conclusions

In summary, physician satisfaction is not a static parameter, but a dynamic entity mediated by both physician‐related and job‐related factors, the majority of which are modifiable. Thus hospitalists and hospital medicine program leaders can be optimistic that uncovering the presence of dissatisfaction through surveys, and addressing the issues triggering it, should enhance physician satisfaction. With improved awareness of mitigating factors of dissatisfaction and commitments to improvement, there is reason for hope. It is unreasonable to believe that dissatisfaction is intrinsic to any medical profession. It is reasonable to believe that physician satisfaction, with all of its desirable implications, can be attained through continual research and prioritization.

The burden of dissatisfaction among medical professionals concerns both physicians and policy makers, especially given the potential ramifications on the work force.1, 2 Abundant research documents a strong relationship between low levels of physician satisfaction and burnout,37 intention to leave,6, 815 and job turnover.13, 1618 Moreover, low physician satisfaction is associated with self‐reported psychiatric symptoms1921 and poorer perceived mental health.22 Not surprisingly, dissatisfied physicians are less likely to recommend to medical students that they pursue their specialty.23

Importantly, physician satisfaction appears to benefit patients. Several studies show a positive relationship between higher physician satisfaction and patient satisfaction and outcomes.2426 Patients cared for by satisfied physicians declare more trust and confidence in their physicians, have better continuity, higher ratings of their care,26, 27 lower no‐show rates,25 and enhanced adherence to their medical care.28 There is also some evidence that higher job satisfaction is associated with lower likelihood of patient errors and suboptimal patient care.29

Physician satisfaction can be influenced by factors intrinsic to the individual physician (age, gender, race, and specialty) and extrinsic to the physician (work environment, practice setting, patient characteristics, and income).22, 30 In this way, satisfaction is not a static property in any physician or physician group, but reflects a dynamic interplay among the expectations and environments within which they work. Although each physician, physician group, and specialty has distinct factors that affect satisfaction, none are immune to potential dissatisfaction.

Given the documented impact of physician satisfaction on multiple aspects of healthcare delivery, we undertook a systematic review of the existing literature to achieve a greater understanding of the current state of U.S. physician satisfaction. In addition, we sought to identify the major survey tools used to measure satisfaction and the characteristics intrinsic and extrinsic to the physician that are associated with satisfaction. We conclude by suggesting needed additional research.

Materials and Methods

We performed a literature search of MEDLINE (

Results

Of the 97 studies, 69 were cross‐sectional (distributed to purposive and often convenience samples of physicians) with sampling sizes ranging from 39 to 6441 and response rates ranging from 31% to 97% (Appendix 1). The other 28 were from larger nationally representative studies (Table 1), including the CTS (n = 92, 45, 71, 74, 91, 102, 104106), RWJS (n = 81, 18, 3334, 39, 40, 60, 61), PWS (n = 711, 22, 23, 55, 83, 92, 99), and WPHS (n = 444, 4951). Fourteen articles reported information from longitudinal (n = 2)18, 86 or repeated cross‐sectional studies (n = 12)1, 2, 39, 73, 76, 79, 85, 91, 96, 97, 102, 110 to help determine satisfaction trends. The survey instruments from the 4 national physician surveys are outlined in Table 1. The types of satisfaction reported are outlined in Figure 2.

| Survey | Satisfaction Measured | MD Type Sampled | Sampled/Responded/Adjusted Response [n/n/% (year of survey)] |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| PWS | 150‐item survey; 3 satisfaction domains (job, career, and specialty; all 5‐point Likert scales); 10 satisfaction facets | AMA Masterfile; random sample; FP, IM, IM specialists, pediatrics, and pediatric specialists | 5704/2326/52% |

| CTS | Career satisfaction (5 point Likert scale) | AMA Masterfile; random sample; all physicians in direct patient care 20+ hours a week | 19054/12385/65% (1996); 20131/12280/61% (1998); 20998/12389/59% (2000) |

| RWJ | Practice satisfaction (4‐point Likert scale); career satisfaction (3‐point Likert scale) | AMA Masterfile; random sample; 1987: physicians <40 years old in practice 1‐6 years; 1991: physicians <45 years old in practice 2‐9 years; 1997: physicians <52 years old in practice 8‐17 years | 8379/5865/70% (1987); 9745/4373/70% (1991); 2093/1549/74% (1997) |

| WPHS | Career satisfaction (5‐point Likert scale) | AMA Masterfile; random sample; female medical school graduates from 1950 to 1989 | 4501/2656/59% |

Trends in U.S. Physician Satisfaction

The CTS physician survey used sophisticated large‐scale random sampling methods and consistent questionnaires, thus allowing assessment of trends. From these repeated cross‐sectional surveys, career satisfaction from 1996 to 2001 was stable (81% to 80% among primary care physicians [PCPs], and 81% to 81% among specialists), although the portion of PCPs who report being very satisfied declined from 42% to 38% (P < 0.001) with no significant change for specialists (43% to 42%; P = 0.20).2

The RWJ surveys found small overall declines. From 1991 to 1997, practice satisfaction declined from 86% to 79%, and career satisfaction declined 96% to 88% (P = not available [NA]).1 A comparison of the 1991 RWJ survey to a 1996 age‐matched California physician survey and also found practice satisfaction declined slightly (86% to 82%, P = NA; very satisfied declined 48% to 37%, P = 0.05).39

Two studies of PCPs in Massachusetts found similar modest declines. The first found practice satisfaction declined from 80% to 66% (1996 to 1999; P < 0.001),73 and the second found a nonsignificant decline in professional satisfaction from 81% to 73% (1986 to 1997; P = not significant [NS]).85 Other studies of specific physician populations found insignificant changes in satisfaction levels during the study periods.76, 79, 86, 91, 96, 97, 110 In summary, recent overall physician satisfaction is relatively unchanged, although there may be modest declines in PCPs and young physicians who report high satisfaction, as evidenced from the CTS, RWJ studies, and other small physician cohorts.

Major Characteristics Associated with Physician Satisfaction

Both factors intrinsic to the physician and characteristics of the job influence physician satisfaction (Figure 3). Intrinsic physician factors are typically not changeable when developing strategies to improve satisfaction. However, they do significantly affect what physicians consider important when choosing a job, and influence how physicians respond to changes in the job. Job characteristics, or extrinsic factors, are generally considered more modifiable when developing institutional strategies to improve satisfaction. Although the intrinsic factors are seemingly unmodifiable, one must take them into account when assessing satisfaction in order to determine the independent effects that the more modifiable extrinsic factors have on satisfaction. The next section describes the variables associated with satisfaction, from the 37 studies that utilized multivariate analyses (Appendix 2) to control for other factors (Appendix 3).

Physician Factors

Physician Age

Age is likely weakly but independently associated with satisfaction, although interpretation is limited by the heterogeneity of the physician samples and the manner in which age is reported. Of the 18 studies that evaluated age, 3 (from the PWS, WPHS, and 1 other) found a weak but positive association.9, 23, 50 Five (from the CTS and others) found a U‐shaped relationship (those at the extremes of age were the most satisfied),59, 68, 70, 71, 74 and 3 found an inverse association (2 CTS PCP subsets, and 1 small single‐county study.35, 45, 106 Six found no association, of which only 1 was from a nationally representative sample (PWS PCPs).5, 96, 97, 109, 110, 112

As a surrogate for age, 6 studies evaluated years in practice or years since medical school graduation. Of these, 2 found a weak but positive association (although only seen in specialists, not PCPs in the CTS),89, 104 and 1 found a negative association (when dichotomized),73 with no association in 3 smaller studies.5, 56, 88

These studies support that age is weakly but independently associated with physician satisfaction when studied as a continuous variable. When studied within various age brackets, studies support a U‐shaped association, with the highest satisfaction in those at the extremes of ages, although this may not be true for PCPs. In addition, the association with older age may be the result of less satisfied physicians leaving the profession.

Physician Gender

The association between gender and overall satisfaction is difficult to interpret due to the heterogeneity of the satisfaction assessments and included confounders, although there may be gender differences in facets of satisfaction. Of the 22 studies that evaluated gender, 3 found an independent effect for women (PWS general internal medicine [GIM] sample, CTS, and 1 other),23, 104, 110 3 for men,41, 81, 98 and no gender effect in the others. Those that found men with higher satisfaction included 1 national study of family practitioners (FPs)98 and 2 academic studies, the latter of which found men with or without children with higher satisfaction compared to women with children, indicating children (or work life balance) may confound gender satisfaction.41, 81

Other national studies, including the CTS and PWS, did not find a gender difference in overall satisfaction,9, 35, 45, 56, 59, 68, 71, 73, 74, 88, 89, 96, 97, 106, 109 although the PWS did find differences in facets of satisfaction (women were more satisfied with relationships with colleagues and patients, but less satisfied with autonomy, pay, resources, and community relationships).83

In summary, the relationship between gender and overall satisfaction is likely confounded by many factors, and its independent effect is difficult to quantify given the heterogeneity of the studies reviewed. There may be gender differences in facets of satisfaction, evaluated only in the PWS.

Physician Race/Ethnicity

There were only 5 multivariate studies delineating the association of race/ethnicity with satisfaction, of which 4 found no difference.35, 50, 56, 88 One study found lower satisfaction in minorities compared to whites, but was only a small sample of preventive medicine physicians.93 Given the growing racial and ethnic diversity of physicians, future research should further explore this association.

Physician Specialty

Overall, pediatricians appear to have higher, and GIM to have lower, satisfaction when compared among the PCPs or specialists, although the interpretation is limited by the heterogeneity of the specialties included, how the specialties are demarcated, and the composition of the reference group.

Of the 17 studies that evaluated specialty, 6 found pediatricians had higher satisfaction (including the CTS),5, 70, 73, 74, 104, 106 and 5 found GIM to have lower satisfaction (including the CTS and PWS)5, 11, 74, 104, 106 than various other comparison groups. Generalized interpretation of the other studies is difficult, as 8 of the 11 arise from very specific convenience samples of physicians (within a state or county).35, 56, 68, 73, 89, 96, 97, 109

Job Factors

Job Demand

There is evidence of a relationship between subjective, but not objective, job demands and satisfaction (categorized in the literature as work stress/pressure, workload, and work hours). Of the 10 studies that evaluated various types of perceived work stress/pressure, 9 found a significant association with dissatisfaction.5, 11, 22, 23, 45, 50, 68, 98, 104

Of the 8 studies that evaluated workload, 4 of them evaluated subjective workload and found too much or too little was associated with dissatisfaction.50, 86, 107, 110 The other 4 evaluated actual number of visits (per week or per hour); 3 did not find an association5, 56, 68 and 1 found a weak but negative association with satisfaction.70

Of the 13 studies that evaluated work hours, 8 found no association (including the PWS, CTS, and WPHS).23, 50, 73, 88, 89, 104, 107, 112 Only 1 found a positive association; however, these results were from a stepwise regression analysis in which work stress had already been controlled for in the model, and a separate stepwise regression showed more work hours to be associated with higher stress levels.98 One found satisfaction with work hours had a strong association with overall satisfaction (but not actual work hours).86 Three found a weak negative association, the last of which found that a recent increase in work hours was significantly associated with dissatisfaction, but not actual work hours.2, 70, 84

Of the 3 studies that evaluated on‐call frequency, 2 found higher call frequency to be moderately negatively associated70, 88 and 1 found no association.50

In summary, there is unequivocal evidence that an imbalance between expected and experienced stress, pressure, or workload is moderately associated with dissatisfaction, but there is less evidence of a significant association with objective workload or work hours. On‐call duty may moderately negatively influence satisfaction, although based only on 2 small studies.

Job Control/Autonomy

There is also a strong association with satisfaction and physician control over elements in their work place. Although the studies are heterogeneous in their assessment of work control and autonomy, 15 of the 16 studies found these dimensions to be strongly and significantly associated with satisfaction.1, 2, 5, 20, 45, 50, 56, 68, 71, 86, 96, 97, 104, 107, 109, 112

Relationship with Colleagues

All 5 studies associating relationship with colleagues with satisfaction found the perception of collegial support/emnteraction to exert a moderate independent effect on satisfaction.5, 20, 89, 104, 112

Part‐time Work Status

Of the 3 studies that evaluated this factor in multivariate analysis, 2 did not find a significant association,71, 110 and 1 reported higher satisfaction with full time work (but did not report statistical values).9 Given the number of U.S. physicians working part time, this warrants further research.

Practice Characteristics (Size/Setting/Site/Ownership)

The interpretation of practice characteristics and satisfaction is limited by the heterogeneity in the way the studies partitioned the practice characteristics, and the reference group composition. Of the 10 studies that evaluated several types of practice settings, 5 found solo or small (1‐2 person) practice sizes more likely associated with dissatisfaction than larger practice sizes.88, 97, 104106 The PWS and CTS obstetrician‐gynecologist (ob‐gyn) subset also found health maintenance organization (HMO) satisfaction to be lower compared to various comparisons11, 71 (although the PWS GIM subset did not find a difference).23 Of the 6 surveys evaluating academic/medical school as the reference group, 4 found higher satisfaction with academics (including 2 from the CTS),9, 71, 104, 110 but 2 smaller studies did not find a difference with university affiliation or teaching.88, 96 Of those studies evaluating single vs. multispecialty groups, only 1 found single‐specialty with higher satisfaction than multispecialty89 and 3 others did not find a difference.56, 68, 73

Regarding practice size, 3 of the 4 found no association with satisfaction.56, 109, 110, 112 Only the CTS evaluated practice region and community size and found rural physicians, those in small metropolitan areas, and those in New England and West North central regions had higher satisfaction.45, 71, 74 The CTS also supports that physicians that are part‐owners or nonowners of their practice have higher satisfaction than full owners.45, 74

In summary, practice characteristics may influence physician satisfaction. Physicians in solo and HMO practices may be less satisfied than physicians in other practice settings and sizes, and academic affiliation may have a small but significant association with satisfaction. Practice size and single vs. multispecialty does not appear to significantly affect satisfaction, and satisfaction association with practice region, community size, and ownership is drawn primarily from the CTS and requires further study.

Patient‐payer Mix and Insurance Status

Capitation and provider‐managed care training does appear to affect satisfaction, but managed care or patient insurance status does not. Of the 9 studies that addressed the influence of managed care or capitation on satisfaction, the percentage of managed care practice revenue, number of managed care contracts, or percentage of managed care patients in a practice had no association with satisfaction.2, 71, 73, 74, 104, 105, 109, 112 Two studies did find that capitation was associated with provider dissatisfaction.2, 68 One CTS study found career satisfaction increased in states after the implementation of patient protection acts (implying physician satisfaction increased with less managed care control and more patient/provider empowerment).102 Two other studies found that physicians with training in managed care and positive attitudes about managed care were more likely to be satisfied.98, 112

Regarding insurance status, 3 studies of PCPs in different states did not find an association between satisfaction and insurance (private, none, Medicare, or Medicaid),35, 68, 89 although a study of rural PCPs found more dissatisfaction in those who reported a recent decrease in the number of patients with adequate insurance.84

In summary, there is unlikely an independent effect of patient‐payer mix or managed care on satisfaction. However, capitation may exert a negative effect, and managed care training (and attitude) may exert a positive effect.

Patient Characteristics

Most patient factors were not found to be independently associated with physician satisfaction, including patient complexity,23, 112 patient demands,5, 20 or specific patient demographics.56 The PWS and CTS studies found physicians who value and are able to maintain long‐term patient relationships were more satisfied.45, 104, 112 One study found that those who perceive patients lack confidence in physicians were more likely to be dissatisfied.109 In summary, patient characteristics do not appear to influence provider satisfaction, but a provider's value of, and ability to maintain, long‐term relationships, as well as their perception of patient trust, may influence satisfaction.

Income

Of the 14 studies that evaluated income, 11 found a positive association (the CTS, RWJ, and others) with actual income1, 2, 45, 74, 84, 88, 93, 104 and income satisfaction.97, 98, 109 Of the 3 that did not find an association with actual income, 2 were from the PWS,23, 112 and 1 from the CTS ob‐gyn subset.71

In summary, the association between actual income and satisfaction may be confounded by other variables (such as work hours and part‐time status), but satisfaction with income does appear to correlate with overall satisfaction.

Incentives

There does appear to be a moderate satisfaction association with the types of income incentives. The CTS studies found more satisfied physicians were those with the ability to make clinical decisions without affecting one's income (although that was not found for the PCP subset).45, 104, 106 Other studies found more satisfaction in those reporting a practice with incentives/emphasis based on quality, and less satisfaction in those with incentives/emphasis based on productivity or service reduction.1, 57, 112 Therefore, the evidence favors higher satisfaction with incentives based on quality rather than productivity or utilization.

Other Physician Factors

Board certification may be modestly positively associated with satisfaction, and being a foreign medical graduate may be modestly negatively associated with satisfaction, although this is limited to few studies.9, 45, 74, 98, 104, 106 Other physician characteristics, such as personal matters (marital status, home stress, mental health, personal satisfaction), work matters (amount of charity care they provide and history of work harassment), and personality (reform mindedness and tolerance for uncertainty) require further research.50, 56, 88, 98, 104

Discussion

Our review of satisfaction trends for U.S. physicians revealed relative stability except for a slight decline among PCPs. We found factors significantly associated with satisfaction to include both physician (age and specialty) and job factors (work demand, work control, colleague support, ability to maintain patient relationships, practice setting, income satisfaction, and incentive types). Based on limited data, the association with race/ethnicity and part‐time work requires more research, and factors that do not appear to have an independent effect on satisfaction include physician gender, patient‐payer mix, and patient characteristics.

As the fastest growing specialty in the history of American medicine, hospital medicine should focus on career satisfaction as a top priority in shaping the future of the more than 20,000 hospitalists now practicing. Although the term hospitalist was coined less than 15 years ago114 the demand for hospitalists is expected to grow to as many as 50,000 by 2020.115 In this time of rapid growth, in order to mold a sustainable specialty, we must all recognize the factors that contribute to satisfaction and strive to maintain good job‐person fit. For individual hospitalists, all of these mediators of satisfaction should be considered when contemplating employment. To ensure a mutual fit, each physician must reflect on how their goals and values coincide with those of the program they are considering. For hospital medicine program leaders, areas of program‐specific dissatisfaction must be continually sought and addressed.

In this review, the variables with the strongest associations with satisfaction that are most pertinent to hospitalists are work demand, control, income/emncentives, and collegial relationships. These variables coincide with the 4 pillars of career satisfaction identified in the Society of Hospital Medicine Career Satisfaction Task Force.116 Perceived work stress/pressure and objective workload can easily (and serially) be measured, and the latter can be compared to national benchmarks to ensure appropriate workload expectations.116 Reducing work pressure/stress may involve assessing and matching variations in workload with manpower, reducing nonclinical tasks by utilizing administrative assistants or physician extenders, or having an emergency plan for unexpected absences. Autonomy and control can be assessed by the job‐fit questionnaire to identify programwide and physician‐specific areas of potential discontent.116 Increasing autonomy/control may involve pursuing leadership within hospital projects or committees, creatively scheduling flexibility, and seeking support from hospital administration. Income expectations should also be couched within national benchmarks, and incentive programs should reflect work quality rather than quantity. Collegial support can be enhanced by instituting a mentoring program, journal club, regular social function, or configuration of offices spaces to allow proximity. Although the conclusions of this review are limited by the lack of hospitalists included in the studies and our inability to perform a meta‐analysis, we believe extrapolation of this information to hospitalist physicians is valid and appropriate. That said, future studies specifically addressing hospitalist satisfaction are needed to ensure this.

Conclusions

In summary, physician satisfaction is not a static parameter, but a dynamic entity mediated by both physician‐related and job‐related factors, the majority of which are modifiable. Thus hospitalists and hospital medicine program leaders can be optimistic that uncovering the presence of dissatisfaction through surveys, and addressing the issues triggering it, should enhance physician satisfaction. With improved awareness of mitigating factors of dissatisfaction and commitments to improvement, there is reason for hope. It is unreasonable to believe that dissatisfaction is intrinsic to any medical profession. It is reasonable to believe that physician satisfaction, with all of its desirable implications, can be attained through continual research and prioritization.

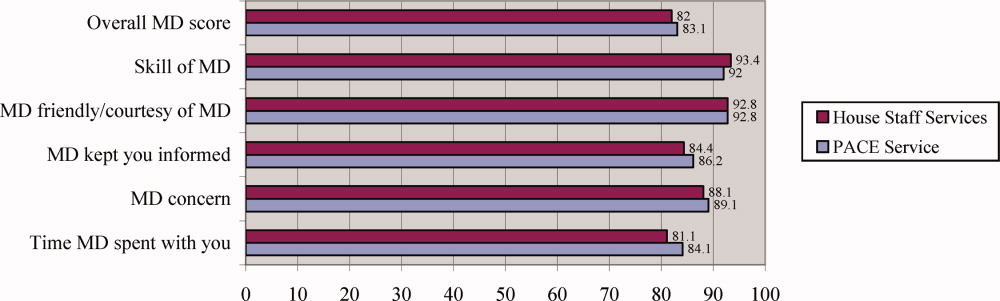

Physician Assistant/Hospitalist Service

Midlevel providers (physician assistants and nurse practitioners) have long been employed by academic medical centers, predominantly on surgical services, or on medical subspecialty services, where they have typically had a limited scope of practice, focused in a narrowly defined area or set of procedures.17 In contrast, there are relatively few reports of experiences deploying midlevel providers to replace house staff on inpatient general medicine services in academic centers,810 and few studies of the effect of midlevel providers on quality and efficiency of care in the academic setting. Despite this, reductions in house officer duty hours as mandated by the Accreditation Council on Graduate Medical Education (ACGME)11 have resulted in academic centers increasingly using midlevel providers to decrease house staff workload on inpatient services.12, 13 In general, midlevel practitioners on general medicine services have been deployed to: (1) care for a population of patients separate from and in parallel with house staff; this population may be narrowly defined (eg, patients with chest pain) or not; (2) assist with the management of patients cared for by house staff by performing certain tasks (eg, scheduling appointments, discharging patients). Even as midlevel providers become more prevalent on academic general medicine services, the best model of care incorporating them into clinical care remains unclear, and few studies have rigorously examined the care provided on services that use them.

We developed an inpatient general medicine service within a large academic medical center staffed by physician assistants and hospitalists to help our residency program meet ACGME duty hour requirements. We hypothesized that by creating a service that is geographically localized and supervised by full‐time hospitalists, by instituting multidisciplinary rounds, and by investing in the professional development of highly‐skilled physician assistants, we could provide care for medically complex, acutely ill general medicine inpatients with similar quality and efficiency as compared to house staff teams. We report our experience during the first year of implementing the service, and compare quality and efficiency of care on this service with that of our traditional house staff services. We also evaluate the effects of this service on patient satisfaction and self‐reported house staff workload.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Study Setting

The study was conducted in a 747‐bed urban, academic medical center in the northeastern United States. The hospital's human research committee reviewed and approved the study design. The hospital has accredited residency and fellowship programs in all major specialties. Prior to July 2005, physician assistants were employed only on surgical and medical subspecialty services (ie, bone marrow transplant, interventional cardiology); none were employed on the inpatient general medicine service. There were approximately 44,000 inpatient admissions during the year of the study, with approximately 6500 of these to the general medicine service.

Description of the General Medicine Service

The General Medicine Service consisted of 8 traditional house staff teams, with 1 attending, 1 junior or senior resident, 2 interns, and 1 or 2 medical students. These teams admitted patients on a rotating basis every fourth day. On 4 of these teams, the attending was a hospitalist, with clinical responsibility for the majority of the patients admitted to the team. On the remaining 4 teams, the teaching attending was a primary care physician or medical subspecialist, responsible for the direct care of a small number of the team's patients, with the remainder cared for by private primary care physicians or subspecialists.

Description of the Physician Assistant/Hospitalist Service

The Physician Assistant/Clinician Educator (PACE) service opened in July 2005, and consisted of 15 beds localized to 2 adjacent inpatient pods, staffed by a single cadre of nurses and medically staffed by 1 hospitalist and 2 physician assistants from 7:00 AM to 7:00 PM on weekdays and by 1 hospitalist, 1 physician assistant, and 1 moonlighter (usually a senior medical resident or fellow) from 7:00 AM to 7:00 PM on weekends. A moonlighter, typically a senior resident or medical subspecialty fellow, admitted patients and covered nights on the service from 7:00 PM to 7:00 AM 7 days a week. The daily census goal for the service was 15 patients, limited by the number of available beds on the 2 pods, and the service accepted admissions 24 hours per day, 7 days per week, whenever beds were available. Daily morning rounds occurred at 8:00 AM and included the hospitalist, physician assistants, nurses, a care coordinator, and a pharmacist. The PACE service did not have triage guidelines related to diagnosis, complexity, or acuity, but only accepted patients via the emergency department or via a primary care physician's office, and did not accept patients transferred from outside hospitals or from the intensive care units.

Physician Assistants

All of the physician assistants on the PACE service had prior inpatient medicine experience, ranging from 6 months to 5 years. The physician assistants worked in 3‐day to 6‐day blocks of 12‐hour shifts. Their clinical responsibilities were similar to those of interns at the study hospital, and included taking histories and performing physical examinations, writing notes and orders, reviewing and assimilating data, creating and updating patient signouts, completing discharge summaries, consulting other services as needed, and communicating with nurses and family members.

Many physician assistants also had nonclinical responsibilities, taking on physician‐mentored roles in education, quality improvement, and administration. They were involved in several initiatives: (1) developing a physician assistant curriculum in hospital medicine, (2) presenting at hospital‐wide physician assistant grand rounds, (3) surveying and tracking patient and family satisfaction on the service, (4) reviewing all 72‐hour hospital readmissions, intensive care unit transfers, and deaths on the service, and (5) maintaining the service's compliance with state regulations regarding physician assistant scope of practice and prescribing.

Hospitalists