User login

All together now: Impact of a regionalization and bedside rounding initiative on the efficiency and inclusiveness of clinical rounds

Attending rounds at academic medical centers are often disconnected from patients and non-physician care team members. Time spent bedside is consistently less than one third of total rounding time, with observational studies reporting a range of 9% to 33% over the past several decades.1-8 Rounds are often conducted outside patient rooms, denying patients, families, and nurses the opportunity to participate and offer valuable insights. Lack of bedside rounds thus limits patient and family engagement, patient input into the care plan, teaching of the physical examination, and communication and collaboration with nurses. In one study, physicians and nurses on rounds engaged in interprofessional communication in only 12% of patient cases.1 Studies have found interdisciplinary bedside rounds have several benefits, including subjectively improved communication and teamwork between physicians and nurses; increased patient satisfaction, including feeling more cared for by the medical team; and decreased length of stay and costs of care.2-10

However, there are many barriers to conducting interdisciplinary bedside rounds at large academic medical centers. Patients cared for by a single medical team are often geographically dispersed to several nursing units, and nurses are unable to predict when physicians will round on their patients. This situation limits nursing involvement on rounds and keeps doctors and nurses isolated from each other.2 Regionalization of care teams reduces this fragmentation by facilitating more interaction among doctors, patients, families, and nursing staff.

There are few data on how regionalized patients and interdisciplinary bedside rounds affect rounding time and the nature of rounds. This information is needed to understand how these structural changes mediate their effects, whether other steps are required to optimize outcomes, and how to maximize efficiency. We used time-motion analysis (TMA) to investigate how regionalization of medical teams, encouragement of bedside rounding, and systematic inclusion of nurses on ward rounds affect amount of time spent with patients, nursing presence on rounds, and total rounding time.

METHODS

Setting

This prospective interventional study, approved by the Institutional Review Board of Partners HealthCare, was conducted on the general medical wards at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, an academic 793-bed tertiary-care center in Boston, Massachusetts. Housestaff teams consist of 1 attending, 1 resident, and 2 interns with or without a medical student. Before June 20, 2013, daily rounds on medical inpatients were conducted largely on the patient unit but outside patient rooms. After completing most of a rounding discussion outside a patient’s room, the team might walk in to examine or speak with the patient. A typical medical team had patients dispersed over 7 medical units on average, and over as many as 13. As nurses were unit based, they did not consistently participate in rounds.

Intervention

In June 2013, as part of a general medical service care redesign initiative, the general medical teams were regionalized to specific inpatient units. The goal was to have teams admit patients predominantly to the team’s designated unit and to have all patients on a unit be cared for by the unit’s assigned team as often as possible, with an 85% goal for both. Toward those ends, the admitting structure was changed from a traditional 4-day call cycle to daily admitting for all teams, based on each unit’s bed availability.11

Teams were also expected to conduct rounds with nurses, and a system for facilitating these rounds was established. As physician and nurse care teams were now geographically co-located, it became possible for residents and nurses to check a rounding sheet for the planned patient rounding order, which had been set by the resident and nurse-in-charge before rounds. No more than about 5 minutes was needed to prepare each day’s order. The rounding sheet prioritized sick patients, newly admitted patients, and planned morning discharges, but patients were also always grouped by nurse. For example, the physician team rounded with the first nurse on all 3 of a nurse’s patients, and then proceeded to the next group of 3 patients with the next nurse, until all patients were seen.

Teams were encouraged to conduct patient- and family-centered rounds exclusively at bedside, except when bedside rounding was thought to be detrimental to a patient (eg, one with delirium). After an intern’s bedside presentation, which included a brief summary and details about overnight events and vital signs, the concerns of the patient, family, and nurse were shared, a focused physical examination performed, relevant data (eg, laboratory test results and imaging studies) reviewed, and the day’s plan formulated. The entire team, including the attending, was expected to have read new patients’ admission notes before rounds. Bedside rounds could thus be focused more on patient assessment and patient/family engagement and less on data transfer.

Several actions were taken to facilitate these changes. Residents, attendings, nurses, and other interdisciplinary team members participated in a series of focus groups and conferences to define workflows and share best practices for patient- and family-centered bedside rounds. Tips on bedside rounding were included in a general medicine rotation guidebook made available to residents and attendings. At the beginning of each post-intervention general medicine rotation, attendings and residents attended brief orientation sessions to review the new daily schedule, have interdisciplinary huddles, and share expectations for patient- and family-centered bedside rounds. On the general medicine units, new medical directors were hired to partner with existing nursing directors to support adoption of the workflows. Last, an interdisciplinary leadership team was formed to support the care redesign efforts. This team started meeting every 2 weeks.

Study Design

We used a pre–post analysis to study the effects of care redesign. Analysis was performed at the same time of year for 2 consecutive years to control for the stage of training and experience of the housestaff. TMA was performed by trained medical students using computer tablets linked to a customized Microsoft Access database form (Redmond, Washington). The form and the database were designed with specific buttons that, when pressed, recorded the time of particular events, such as the coming and going of each participant, the location of rounds, and the beginning and the end of rounding encounters with a patient. One research assistant using an Access entry form was able to dynamically track all events in real time, as they occurred. We collected data on 4 teams at baseline and 5 teams after the intervention. Each of the 4 baseline teams was followed for 4 consecutive weekdays—16 rounds total, April-June 2013—to capture the 4-day call cycle. Each of the 5 post-intervention teams was followed for 5 consecutive weekdays—25 rounds total, April–June 2014—to capture the 5-day cycle. (Because of technical difficulties, data from 1 rounding session were not captured.) For inclusion in the statistical analyses, TMA captured 166 on-service patients before the intervention and 304 afterward. Off-service patients, those with an attending other than the team attending, were excluded because their rounds were conducted separately.

We examined 2 primary outcomes, the proportion of time each clinical team member was present on rounds and the proportion of bedside rounding time. Secondary outcomes were round duration, rounding time per patient, and total non-patient time per rounding session (total rounding time minus total patient time).

Statistical Analysis

TMA data were organized in an Access database and analyzed with SAS Version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina). We analyzed the data by round session as well as by patient.

Data are presented as means with standard deviations, medians with interquartile ranges, and proportions, as appropriate. For analyses by round session, we used unadjusted linear regression; for patient-level analyses, we used general estimating equations to adjust for clustering of patients within each session; for nurse presence during any part of a round by patient, we used a χ2 test. Total non-patient time per round session was compared with use of patient-clustered general estimating equations using a γ distribution to account for the non-normality of the data.

RESULTS

Patient and Care Team Characteristics

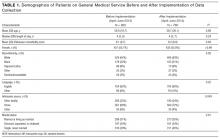

Over the first year of the initiative, 85% of a team’s patients were on their assigned unit, and 87% of a unit’s patients were with the assigned team. Census numbers were 10.4 patients per general medicine team in April-June 2013 and 12.7 patients per team in April-June 2014, a 22% increase after care redesign. There were no statistically significant differences in patient characteristics, including age, sex, race, language, admission source, and comorbidity measure (Elixhauser score), between the pre-intervention and post-intervention study periods, except for a slightly higher proportion of patients admitted from home and fewer patients admitted directly from clinic (Table 1).

Primary Outcomes

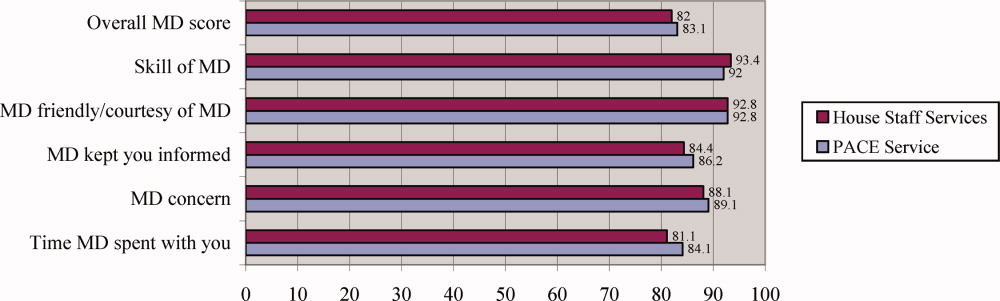

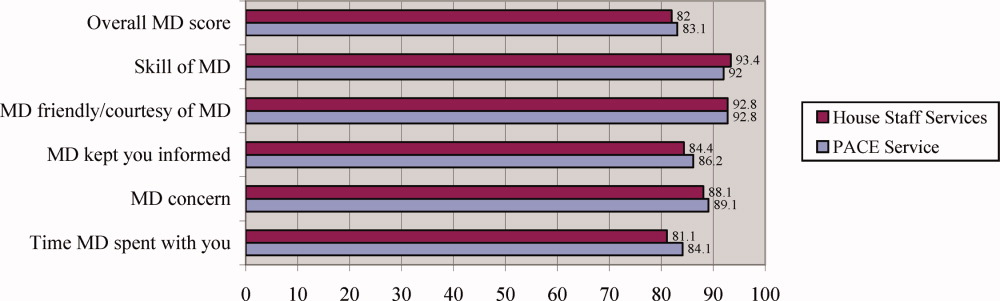

Mean proportion of time the nurse was present on rounds per round session increased significantly (P < 0.001), from 24.1% to 67.8% (Figure 1A, Table 2). For individual patient encounters, the increased overall nursing presence was attributable to having more nurses on rounds and having nurses present for a larger proportion of individual rounding encounters (Figure 1B, Table 2). Nurses were present for at least some part of rounds for 53% of patients before the intervention and 93% afterward (P < 0.001). Mean proportion of round time by each of the 2 interns on each team decreased from 59.6% to 49.6% (P = 0.007).

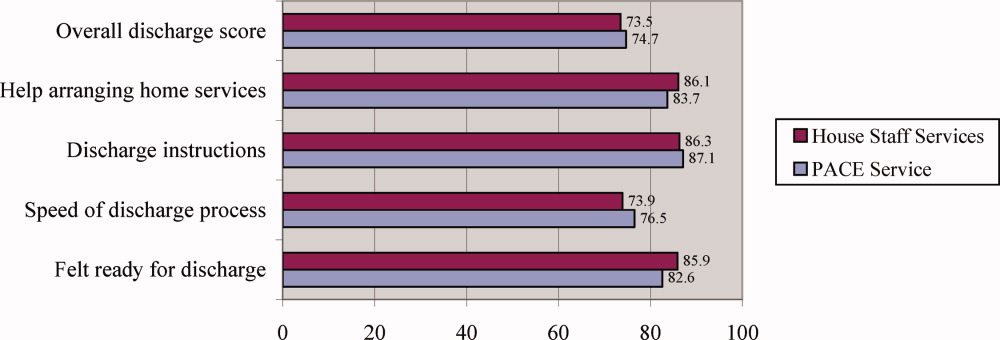

Total bedside rounding time increased significantly ( P < 0.001), from 39.9% before the intervention to 55.8% afterward (Table 2). Meanwhile, percentage of rounding time spent on the unit but outside patient rooms decreased significantly ( P = 0.004), from 55.2% to 42.2%, as did rounding time on a unit completely different from the patient’s (4.9% before intervention, 2.0% afterward; P = 0.03). Again, patient-level results were similar (Figure 2, Table 2), but the decreased time spent on the unit, outside the patient rooms, was not significant.

Secondary Outcomes

Total rounding time decreased significantly, from a mean of 182 minutes (3.0 hours) at baseline to a mean of 146 minutes (2.4 hours) after the intervention, despite the higher post-intervention census. (When adjusted for patient census, the difference increased from 35.5 to 53.8 minutes; Table 2.) Mean rounding time per patient decreased significantly, from 14.7 minutes at baseline to 10.5 minutes after the intervention. For newly admitted patients, mean rounding time per patient decreased from 30.0 minutes before implementation to 16.3 minutes afterward. Mean rounding time also decreased, though much less, for subsequent-day patients (Table 2). For both new and existing patients, the decrease in rounding time largely was a reduction in time spent rounding outside patient rooms, with minimal impact on bedside time (Table 2). Mean time nurses were present during a patient’s rounds increased significantly, from 4.5 to 8.0 minutes (Table 2). Total nurse rounding time increased from 45.1 minutes per session to 98.8 minutes. Rounding time not related to patient discussion or evaluation decreased from 22.7 minutes per session to 13.3 minutes ( P = 0.003).

DISCUSSION

TMA of our care redesign initiative showed that this multipronged intervention, which included team regionalization, encouragement of bedside rounding with nurses, call structure changes, and attendings’ reading of admission notes before rounds, resulted in an increased proportion of rounding time spent with patients and an increased proportion of time nurses were present on rounds. Secondarily, round duration decreased even as patient census increased.

Regionalized teams have been found to improve interdisciplinary communication.1 The present study elaborates on that finding by demonstrating a dramatic increase in nursing presence on rounds, likely resulting from the unit’s use of rounding schedules and nurses’ prioritization of rounding orders, both of which were made possible by geographic co-localization. Other research has noted that one of the most significant barriers to interdisciplinary rounds is difficulty coordinating the start times of physician/nurse bedside rounding encounters. The system we have studied directly addresses this difficulty.9 Of note, nursing presence on rounds is necessary but not sufficient for true physician–nurse collaboration and effective communication,1 as reflected in a separate study of the intervention showing no significant difference in the concordance of the patient care plan between nurses and physicians before and after regionalization.12 Additional interventions may be needed to ensure that communication during bedside rounds is effective.

Our regionalized teams spent a significantly higher proportion of rounding time bedside, likely because of a cultural shift in expectations and the increased convenience of seeing patients on the team’s unit. Nevertheless, bedside time was not 100%. Structural barriers (eg, patients off-unit for dialysis) and cultural barriers likely contributed to the less than full adoption of bedside rounding. As described previously, cultural barriers to bedside rounding include trainees’ anxiety about being questioned in front of patients, the desire to freely exchange academic ideas in a conference room, and attendings’ doubts about their bedside teaching ability.1,9,13 Bedside rounds provide an important opportunity to apply the principles of patient- and family-centered care, including promotion of dignity and respect, information sharing, and collaboration. Thus, overcoming the concerns of housestaff and attendings and helping them feel prepared for bedside rounds can benefit the patient experience. More attention should be given to these practices as these types of interventions are implemented at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and elsewhere.1,13-15

Another primary concern about interdisciplinary bedside rounding is the perception that it takes more time.9 Therefore, it was important for us to measure round duration as a balancing measure to be considered for our intervention. Fortunately, we found round duration decreased with regionalization and encouragement of bedside rounding. This decrease was driven largely by a significant decrease in mean rounding time per new patient, which may be attributable at least in part to setting expectations that attendings and residents will read admission notes before rounds and that interns will summarize rather than recount information from admission notes. However, we also found rounding time decreases for subsequent-day patients, suggesting an underlying time savings. Spending a larger proportion of time bedside may therefore result in more efficient rounds. Bedside presentations can reduce redundancies, such as discussing a patient’s case outside his or her room and subsequently walking in and going over much of the same information with the patient. Our model de-emphasizes data transfer in favor of discussion of care plans. There was also a decrease in non-patient time, likely reflecting reduced transit time for regionalized teams. This decrease aligns with a recent finding that bedside rounding was at least as efficient as rounding outside the room.16

Of note, though a larger percentage of time was spent bedside after implementation of the care redesign, the absolute amount of bedside time did not change significantly. Our data showed that, even with shorter rounds, the same amount of absolute time can be spent bedside, face to face with the patient, by increasing the proportion of bedside rounding time. In other words, teams on average did not spend more time with patients, though the content and the structure of those encounters may have changed. This finding may be attributable to eliminating redundancy, forgoing the outside-the-room discussion, and thus the largest time reductions were realized there. In addition, teams incompletely adopted beside rounds, as reflected in the data. We expect that, with more complete adoption, an even larger proportion of time will be spent bedside, and absolute time bedside might increase as a result.

An unexpected result of the care redesign was that interns’ proportion of rounding time decreased after the intervention. This decrease most likely is attributable to interns’ being less likely to participate in rounds for a co-intern’s patient, and to their staying outside that patient’s room to give themselves more time to advance the care of their own patients. Before the intervention, when more rounding time was spent outside patient rooms, interns were more likely to join rounds for their co-intern’s patients because they could easily break away, as needed, to continue care of their own patients. The resident is now encouraged to use the morning huddle to identify which patients likely have the most educational value, and both interns are expected to join the bedside rounds for these patients.

This study had a few limitations. First, the pre–post design made it difficult to exclude the possibility that other temporal changes may have affected outcomes, though we did account for time-of-year effects by aligning our data-collection phases. In addition, the authors, including the director of the general medical service, are unaware of any co-interventions during the study period. Second, the multipronged intervention included care team regionalization, encouragement of bedside rounding with nurses, call structure changes (from 4 days to daily admitting), and attendings’ reading of admission notes before rounds. Thus, parsing which component(s) contributed to the results was difficult, though all the changes instituted likely were necessary for system redesign. For example, regionalization of clinicians to unit-based teams was made possible by switching to a daily admitting system.

Time that team members spent preparing for rounds was not recorded before or after the intervention. Thus, the decrease in total rounding time could have been accompanied by an increase in time spent preparing for rounds. However, admission notes were available in our electronic medical record before and after the intervention, and most residents and attendings were already reading them pre-intervention. After the intervention, pre-round note reading was more clearly defined as an expectation, and we were able to set the expectation that interns should use their presentations to summarize rather than recount information. In addition, in the post-intervention period, we did not include time spent preparing rounding orders; as already noted, however, preparation took only 5 minutes per day. Also, we did not analyze the content or the quality of the discussion on rounds, but simply recorded who was present where and when. Regarding the effect of the intervention on patient care, results were mixed. As reported in 2016, we saw no difference in frequency of adverse events with this intervention.12 However, a more sensitive measure of adverse events—used in a study on handoffs—showed our regionalization efforts had an additive effect on reducing overnight adverse events.17Researchers should now focus on the effects of care redesign on clinical outcomes, interdisciplinary care team communication, patient engagement and satisfaction, provider opinions of communication, workflow, patient care, and housestaff education. Our methodology can be used as a model to link structure, process, and outcome related to rounds and thereby better understand how best to optimize patient care and efficiency. Additional studies are needed to analyze the content of rounds and their association with patient and educational outcomes. Last, it will be important to conduct a study to see if the effects we have identified can be sustained. Such a study is already under way.

In conclusion, creating regionalized care teams and encouraging focused bedside rounds increased the proportion of bedside time and the presence of nurses on rounds. Rounds were shorter despite higher patient census. TMA revealed that regionalized care teams and bedside rounding at a large academic hospital are feasible, and are useful in establishing the necessary structures for increasing physician–nurse and provider–patient interactions.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Dr. Stan Ashley, Dr. Jacqueline Somerville, and Sheila Harris for their support of the regionalization initiative.

Disclosures

Dr. Schnipper received funding from Sanofi-aventis to conduct an investigator-initiated study to implement and evaluate a multi-faceted intervention to improve transitions of care in patients discharged home on insulin. The study was also supported by funding from the Marshall A. Wolf Medical Education Fund, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, and Dr. Stan Ashley, Chief Medical Officer, Brigham and Women’s Hospital. Some of the content of this article was orally presented at the annual meeting of the Society of Hospital Medicine; March 29-April 1, 2015; National Harbor, MD.

1. Crumlish CM, Yialamas MA, McMahon GT. Quantification of bedside teaching by an academic hospitalist group. J Hosp Med. 2009;4(5):304-307. PubMed

2. Gonzalo JD, Masters PA, Simons RJ, Chuang CH. Attending rounds and bedside case presentations: medical student and medicine resident experiences and attitudes. Teach Learn Med. 2009;21(2):105-110. PubMed

3. Elliot DL, Hickam DH. Attending rounds on in-patient units: differences between medical and non-medical services. Med Educ. 1993;27(6):503-508. PubMed

4. Payson HE, Barchas JD. A time study of medical teaching rounds. N Engl J Med. 1965;273(27):1468-1471. PubMed

5. Tremonti LP, Biddle WB. Teaching behaviors of residents and faculty members. J Med Educ. 1982;57(11):854-859. PubMed

6. Miller M, Johnson B, Greene HL, Baier M, Nowlin S. An observational study of attending rounds. J Gen Intern Med. 1992;7(6):646-648. PubMed

7. Collins GF, Cassie JM, Daggett CJ. The role of the attending physician in clinical training. J Med Educ. 1978;53(5):429-431. PubMed

8. Ward DR, Ghali WA, Graham A, Lemaire JB. A real-time locating system observes physician time-motion patterns during walk-rounds: a pilot study. BMC Med Educ. 2014;14:37. PubMed

9. Gonzalo JD, Kuperman E, Lehman E, Haidet P. Bedside interprofessional rounds: perceptions of benefits and barriers by internal medicine nursing staff, attending physicians, and housestaff physicians. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(10):646-651. PubMed

10. Stickrath C, Noble M, Prochazka A, et al. Attending rounds in the current era: what is and is not happening. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(12):1084-1089. PubMed

11. Boxer R, Vitale M, Gershanik EF, et al. 5th time’s a charm: creation of unit-based care teams in a high occupancy hospital [abstract]. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(suppl 2).

12. Mueller SK, Schnipper JL, Giannelli K, Roy CL, Boxer R. Impact of regionalized care on concordance of plan and preventable adverse events on general medicine services. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(9):620-627. PubMed

13. Chauke HL, Pattinson RC. Ward rounds—bedside or conference room? S Afr Med J. 2006;96(5):398-400. PubMed

14. Wang-Cheng RM, Barnas GP, Sigmann P, Riendl PA, Young MJ. Bedside case presentations: why patients like them but learners don’t. J Gen Intern Med. 1989;4(4):284-287. PubMed

15. Lehmann LS, Brancati FL, Chen MC, Roter D, Dobs AS. The effect of bedside case presentations on patients’ perceptions of their medical care. N Engl J Med. 1997;336(16):1150-1155. PubMed

16. Gonzalo JD, Chuang CH, Huang G, Smith C. The return of bedside rounds: an educational intervention. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(8):792-798. PubMed

17. Mueller SK, Yoon C, Schnipper JL. Association of a web-based handoff tool with rates of medical errors. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(9):1400-1402. PubMed

Attending rounds at academic medical centers are often disconnected from patients and non-physician care team members. Time spent bedside is consistently less than one third of total rounding time, with observational studies reporting a range of 9% to 33% over the past several decades.1-8 Rounds are often conducted outside patient rooms, denying patients, families, and nurses the opportunity to participate and offer valuable insights. Lack of bedside rounds thus limits patient and family engagement, patient input into the care plan, teaching of the physical examination, and communication and collaboration with nurses. In one study, physicians and nurses on rounds engaged in interprofessional communication in only 12% of patient cases.1 Studies have found interdisciplinary bedside rounds have several benefits, including subjectively improved communication and teamwork between physicians and nurses; increased patient satisfaction, including feeling more cared for by the medical team; and decreased length of stay and costs of care.2-10

However, there are many barriers to conducting interdisciplinary bedside rounds at large academic medical centers. Patients cared for by a single medical team are often geographically dispersed to several nursing units, and nurses are unable to predict when physicians will round on their patients. This situation limits nursing involvement on rounds and keeps doctors and nurses isolated from each other.2 Regionalization of care teams reduces this fragmentation by facilitating more interaction among doctors, patients, families, and nursing staff.

There are few data on how regionalized patients and interdisciplinary bedside rounds affect rounding time and the nature of rounds. This information is needed to understand how these structural changes mediate their effects, whether other steps are required to optimize outcomes, and how to maximize efficiency. We used time-motion analysis (TMA) to investigate how regionalization of medical teams, encouragement of bedside rounding, and systematic inclusion of nurses on ward rounds affect amount of time spent with patients, nursing presence on rounds, and total rounding time.

METHODS

Setting

This prospective interventional study, approved by the Institutional Review Board of Partners HealthCare, was conducted on the general medical wards at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, an academic 793-bed tertiary-care center in Boston, Massachusetts. Housestaff teams consist of 1 attending, 1 resident, and 2 interns with or without a medical student. Before June 20, 2013, daily rounds on medical inpatients were conducted largely on the patient unit but outside patient rooms. After completing most of a rounding discussion outside a patient’s room, the team might walk in to examine or speak with the patient. A typical medical team had patients dispersed over 7 medical units on average, and over as many as 13. As nurses were unit based, they did not consistently participate in rounds.

Intervention

In June 2013, as part of a general medical service care redesign initiative, the general medical teams were regionalized to specific inpatient units. The goal was to have teams admit patients predominantly to the team’s designated unit and to have all patients on a unit be cared for by the unit’s assigned team as often as possible, with an 85% goal for both. Toward those ends, the admitting structure was changed from a traditional 4-day call cycle to daily admitting for all teams, based on each unit’s bed availability.11

Teams were also expected to conduct rounds with nurses, and a system for facilitating these rounds was established. As physician and nurse care teams were now geographically co-located, it became possible for residents and nurses to check a rounding sheet for the planned patient rounding order, which had been set by the resident and nurse-in-charge before rounds. No more than about 5 minutes was needed to prepare each day’s order. The rounding sheet prioritized sick patients, newly admitted patients, and planned morning discharges, but patients were also always grouped by nurse. For example, the physician team rounded with the first nurse on all 3 of a nurse’s patients, and then proceeded to the next group of 3 patients with the next nurse, until all patients were seen.

Teams were encouraged to conduct patient- and family-centered rounds exclusively at bedside, except when bedside rounding was thought to be detrimental to a patient (eg, one with delirium). After an intern’s bedside presentation, which included a brief summary and details about overnight events and vital signs, the concerns of the patient, family, and nurse were shared, a focused physical examination performed, relevant data (eg, laboratory test results and imaging studies) reviewed, and the day’s plan formulated. The entire team, including the attending, was expected to have read new patients’ admission notes before rounds. Bedside rounds could thus be focused more on patient assessment and patient/family engagement and less on data transfer.

Several actions were taken to facilitate these changes. Residents, attendings, nurses, and other interdisciplinary team members participated in a series of focus groups and conferences to define workflows and share best practices for patient- and family-centered bedside rounds. Tips on bedside rounding were included in a general medicine rotation guidebook made available to residents and attendings. At the beginning of each post-intervention general medicine rotation, attendings and residents attended brief orientation sessions to review the new daily schedule, have interdisciplinary huddles, and share expectations for patient- and family-centered bedside rounds. On the general medicine units, new medical directors were hired to partner with existing nursing directors to support adoption of the workflows. Last, an interdisciplinary leadership team was formed to support the care redesign efforts. This team started meeting every 2 weeks.

Study Design

We used a pre–post analysis to study the effects of care redesign. Analysis was performed at the same time of year for 2 consecutive years to control for the stage of training and experience of the housestaff. TMA was performed by trained medical students using computer tablets linked to a customized Microsoft Access database form (Redmond, Washington). The form and the database were designed with specific buttons that, when pressed, recorded the time of particular events, such as the coming and going of each participant, the location of rounds, and the beginning and the end of rounding encounters with a patient. One research assistant using an Access entry form was able to dynamically track all events in real time, as they occurred. We collected data on 4 teams at baseline and 5 teams after the intervention. Each of the 4 baseline teams was followed for 4 consecutive weekdays—16 rounds total, April-June 2013—to capture the 4-day call cycle. Each of the 5 post-intervention teams was followed for 5 consecutive weekdays—25 rounds total, April–June 2014—to capture the 5-day cycle. (Because of technical difficulties, data from 1 rounding session were not captured.) For inclusion in the statistical analyses, TMA captured 166 on-service patients before the intervention and 304 afterward. Off-service patients, those with an attending other than the team attending, were excluded because their rounds were conducted separately.

We examined 2 primary outcomes, the proportion of time each clinical team member was present on rounds and the proportion of bedside rounding time. Secondary outcomes were round duration, rounding time per patient, and total non-patient time per rounding session (total rounding time minus total patient time).

Statistical Analysis

TMA data were organized in an Access database and analyzed with SAS Version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina). We analyzed the data by round session as well as by patient.

Data are presented as means with standard deviations, medians with interquartile ranges, and proportions, as appropriate. For analyses by round session, we used unadjusted linear regression; for patient-level analyses, we used general estimating equations to adjust for clustering of patients within each session; for nurse presence during any part of a round by patient, we used a χ2 test. Total non-patient time per round session was compared with use of patient-clustered general estimating equations using a γ distribution to account for the non-normality of the data.

RESULTS

Patient and Care Team Characteristics

Over the first year of the initiative, 85% of a team’s patients were on their assigned unit, and 87% of a unit’s patients were with the assigned team. Census numbers were 10.4 patients per general medicine team in April-June 2013 and 12.7 patients per team in April-June 2014, a 22% increase after care redesign. There were no statistically significant differences in patient characteristics, including age, sex, race, language, admission source, and comorbidity measure (Elixhauser score), between the pre-intervention and post-intervention study periods, except for a slightly higher proportion of patients admitted from home and fewer patients admitted directly from clinic (Table 1).

Primary Outcomes

Mean proportion of time the nurse was present on rounds per round session increased significantly (P < 0.001), from 24.1% to 67.8% (Figure 1A, Table 2). For individual patient encounters, the increased overall nursing presence was attributable to having more nurses on rounds and having nurses present for a larger proportion of individual rounding encounters (Figure 1B, Table 2). Nurses were present for at least some part of rounds for 53% of patients before the intervention and 93% afterward (P < 0.001). Mean proportion of round time by each of the 2 interns on each team decreased from 59.6% to 49.6% (P = 0.007).

Total bedside rounding time increased significantly ( P < 0.001), from 39.9% before the intervention to 55.8% afterward (Table 2). Meanwhile, percentage of rounding time spent on the unit but outside patient rooms decreased significantly ( P = 0.004), from 55.2% to 42.2%, as did rounding time on a unit completely different from the patient’s (4.9% before intervention, 2.0% afterward; P = 0.03). Again, patient-level results were similar (Figure 2, Table 2), but the decreased time spent on the unit, outside the patient rooms, was not significant.

Secondary Outcomes

Total rounding time decreased significantly, from a mean of 182 minutes (3.0 hours) at baseline to a mean of 146 minutes (2.4 hours) after the intervention, despite the higher post-intervention census. (When adjusted for patient census, the difference increased from 35.5 to 53.8 minutes; Table 2.) Mean rounding time per patient decreased significantly, from 14.7 minutes at baseline to 10.5 minutes after the intervention. For newly admitted patients, mean rounding time per patient decreased from 30.0 minutes before implementation to 16.3 minutes afterward. Mean rounding time also decreased, though much less, for subsequent-day patients (Table 2). For both new and existing patients, the decrease in rounding time largely was a reduction in time spent rounding outside patient rooms, with minimal impact on bedside time (Table 2). Mean time nurses were present during a patient’s rounds increased significantly, from 4.5 to 8.0 minutes (Table 2). Total nurse rounding time increased from 45.1 minutes per session to 98.8 minutes. Rounding time not related to patient discussion or evaluation decreased from 22.7 minutes per session to 13.3 minutes ( P = 0.003).

DISCUSSION

TMA of our care redesign initiative showed that this multipronged intervention, which included team regionalization, encouragement of bedside rounding with nurses, call structure changes, and attendings’ reading of admission notes before rounds, resulted in an increased proportion of rounding time spent with patients and an increased proportion of time nurses were present on rounds. Secondarily, round duration decreased even as patient census increased.

Regionalized teams have been found to improve interdisciplinary communication.1 The present study elaborates on that finding by demonstrating a dramatic increase in nursing presence on rounds, likely resulting from the unit’s use of rounding schedules and nurses’ prioritization of rounding orders, both of which were made possible by geographic co-localization. Other research has noted that one of the most significant barriers to interdisciplinary rounds is difficulty coordinating the start times of physician/nurse bedside rounding encounters. The system we have studied directly addresses this difficulty.9 Of note, nursing presence on rounds is necessary but not sufficient for true physician–nurse collaboration and effective communication,1 as reflected in a separate study of the intervention showing no significant difference in the concordance of the patient care plan between nurses and physicians before and after regionalization.12 Additional interventions may be needed to ensure that communication during bedside rounds is effective.

Our regionalized teams spent a significantly higher proportion of rounding time bedside, likely because of a cultural shift in expectations and the increased convenience of seeing patients on the team’s unit. Nevertheless, bedside time was not 100%. Structural barriers (eg, patients off-unit for dialysis) and cultural barriers likely contributed to the less than full adoption of bedside rounding. As described previously, cultural barriers to bedside rounding include trainees’ anxiety about being questioned in front of patients, the desire to freely exchange academic ideas in a conference room, and attendings’ doubts about their bedside teaching ability.1,9,13 Bedside rounds provide an important opportunity to apply the principles of patient- and family-centered care, including promotion of dignity and respect, information sharing, and collaboration. Thus, overcoming the concerns of housestaff and attendings and helping them feel prepared for bedside rounds can benefit the patient experience. More attention should be given to these practices as these types of interventions are implemented at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and elsewhere.1,13-15

Another primary concern about interdisciplinary bedside rounding is the perception that it takes more time.9 Therefore, it was important for us to measure round duration as a balancing measure to be considered for our intervention. Fortunately, we found round duration decreased with regionalization and encouragement of bedside rounding. This decrease was driven largely by a significant decrease in mean rounding time per new patient, which may be attributable at least in part to setting expectations that attendings and residents will read admission notes before rounds and that interns will summarize rather than recount information from admission notes. However, we also found rounding time decreases for subsequent-day patients, suggesting an underlying time savings. Spending a larger proportion of time bedside may therefore result in more efficient rounds. Bedside presentations can reduce redundancies, such as discussing a patient’s case outside his or her room and subsequently walking in and going over much of the same information with the patient. Our model de-emphasizes data transfer in favor of discussion of care plans. There was also a decrease in non-patient time, likely reflecting reduced transit time for regionalized teams. This decrease aligns with a recent finding that bedside rounding was at least as efficient as rounding outside the room.16

Of note, though a larger percentage of time was spent bedside after implementation of the care redesign, the absolute amount of bedside time did not change significantly. Our data showed that, even with shorter rounds, the same amount of absolute time can be spent bedside, face to face with the patient, by increasing the proportion of bedside rounding time. In other words, teams on average did not spend more time with patients, though the content and the structure of those encounters may have changed. This finding may be attributable to eliminating redundancy, forgoing the outside-the-room discussion, and thus the largest time reductions were realized there. In addition, teams incompletely adopted beside rounds, as reflected in the data. We expect that, with more complete adoption, an even larger proportion of time will be spent bedside, and absolute time bedside might increase as a result.

An unexpected result of the care redesign was that interns’ proportion of rounding time decreased after the intervention. This decrease most likely is attributable to interns’ being less likely to participate in rounds for a co-intern’s patient, and to their staying outside that patient’s room to give themselves more time to advance the care of their own patients. Before the intervention, when more rounding time was spent outside patient rooms, interns were more likely to join rounds for their co-intern’s patients because they could easily break away, as needed, to continue care of their own patients. The resident is now encouraged to use the morning huddle to identify which patients likely have the most educational value, and both interns are expected to join the bedside rounds for these patients.

This study had a few limitations. First, the pre–post design made it difficult to exclude the possibility that other temporal changes may have affected outcomes, though we did account for time-of-year effects by aligning our data-collection phases. In addition, the authors, including the director of the general medical service, are unaware of any co-interventions during the study period. Second, the multipronged intervention included care team regionalization, encouragement of bedside rounding with nurses, call structure changes (from 4 days to daily admitting), and attendings’ reading of admission notes before rounds. Thus, parsing which component(s) contributed to the results was difficult, though all the changes instituted likely were necessary for system redesign. For example, regionalization of clinicians to unit-based teams was made possible by switching to a daily admitting system.

Time that team members spent preparing for rounds was not recorded before or after the intervention. Thus, the decrease in total rounding time could have been accompanied by an increase in time spent preparing for rounds. However, admission notes were available in our electronic medical record before and after the intervention, and most residents and attendings were already reading them pre-intervention. After the intervention, pre-round note reading was more clearly defined as an expectation, and we were able to set the expectation that interns should use their presentations to summarize rather than recount information. In addition, in the post-intervention period, we did not include time spent preparing rounding orders; as already noted, however, preparation took only 5 minutes per day. Also, we did not analyze the content or the quality of the discussion on rounds, but simply recorded who was present where and when. Regarding the effect of the intervention on patient care, results were mixed. As reported in 2016, we saw no difference in frequency of adverse events with this intervention.12 However, a more sensitive measure of adverse events—used in a study on handoffs—showed our regionalization efforts had an additive effect on reducing overnight adverse events.17Researchers should now focus on the effects of care redesign on clinical outcomes, interdisciplinary care team communication, patient engagement and satisfaction, provider opinions of communication, workflow, patient care, and housestaff education. Our methodology can be used as a model to link structure, process, and outcome related to rounds and thereby better understand how best to optimize patient care and efficiency. Additional studies are needed to analyze the content of rounds and their association with patient and educational outcomes. Last, it will be important to conduct a study to see if the effects we have identified can be sustained. Such a study is already under way.

In conclusion, creating regionalized care teams and encouraging focused bedside rounds increased the proportion of bedside time and the presence of nurses on rounds. Rounds were shorter despite higher patient census. TMA revealed that regionalized care teams and bedside rounding at a large academic hospital are feasible, and are useful in establishing the necessary structures for increasing physician–nurse and provider–patient interactions.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Dr. Stan Ashley, Dr. Jacqueline Somerville, and Sheila Harris for their support of the regionalization initiative.

Disclosures

Dr. Schnipper received funding from Sanofi-aventis to conduct an investigator-initiated study to implement and evaluate a multi-faceted intervention to improve transitions of care in patients discharged home on insulin. The study was also supported by funding from the Marshall A. Wolf Medical Education Fund, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, and Dr. Stan Ashley, Chief Medical Officer, Brigham and Women’s Hospital. Some of the content of this article was orally presented at the annual meeting of the Society of Hospital Medicine; March 29-April 1, 2015; National Harbor, MD.

Attending rounds at academic medical centers are often disconnected from patients and non-physician care team members. Time spent bedside is consistently less than one third of total rounding time, with observational studies reporting a range of 9% to 33% over the past several decades.1-8 Rounds are often conducted outside patient rooms, denying patients, families, and nurses the opportunity to participate and offer valuable insights. Lack of bedside rounds thus limits patient and family engagement, patient input into the care plan, teaching of the physical examination, and communication and collaboration with nurses. In one study, physicians and nurses on rounds engaged in interprofessional communication in only 12% of patient cases.1 Studies have found interdisciplinary bedside rounds have several benefits, including subjectively improved communication and teamwork between physicians and nurses; increased patient satisfaction, including feeling more cared for by the medical team; and decreased length of stay and costs of care.2-10

However, there are many barriers to conducting interdisciplinary bedside rounds at large academic medical centers. Patients cared for by a single medical team are often geographically dispersed to several nursing units, and nurses are unable to predict when physicians will round on their patients. This situation limits nursing involvement on rounds and keeps doctors and nurses isolated from each other.2 Regionalization of care teams reduces this fragmentation by facilitating more interaction among doctors, patients, families, and nursing staff.

There are few data on how regionalized patients and interdisciplinary bedside rounds affect rounding time and the nature of rounds. This information is needed to understand how these structural changes mediate their effects, whether other steps are required to optimize outcomes, and how to maximize efficiency. We used time-motion analysis (TMA) to investigate how regionalization of medical teams, encouragement of bedside rounding, and systematic inclusion of nurses on ward rounds affect amount of time spent with patients, nursing presence on rounds, and total rounding time.

METHODS

Setting

This prospective interventional study, approved by the Institutional Review Board of Partners HealthCare, was conducted on the general medical wards at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, an academic 793-bed tertiary-care center in Boston, Massachusetts. Housestaff teams consist of 1 attending, 1 resident, and 2 interns with or without a medical student. Before June 20, 2013, daily rounds on medical inpatients were conducted largely on the patient unit but outside patient rooms. After completing most of a rounding discussion outside a patient’s room, the team might walk in to examine or speak with the patient. A typical medical team had patients dispersed over 7 medical units on average, and over as many as 13. As nurses were unit based, they did not consistently participate in rounds.

Intervention

In June 2013, as part of a general medical service care redesign initiative, the general medical teams were regionalized to specific inpatient units. The goal was to have teams admit patients predominantly to the team’s designated unit and to have all patients on a unit be cared for by the unit’s assigned team as often as possible, with an 85% goal for both. Toward those ends, the admitting structure was changed from a traditional 4-day call cycle to daily admitting for all teams, based on each unit’s bed availability.11

Teams were also expected to conduct rounds with nurses, and a system for facilitating these rounds was established. As physician and nurse care teams were now geographically co-located, it became possible for residents and nurses to check a rounding sheet for the planned patient rounding order, which had been set by the resident and nurse-in-charge before rounds. No more than about 5 minutes was needed to prepare each day’s order. The rounding sheet prioritized sick patients, newly admitted patients, and planned morning discharges, but patients were also always grouped by nurse. For example, the physician team rounded with the first nurse on all 3 of a nurse’s patients, and then proceeded to the next group of 3 patients with the next nurse, until all patients were seen.

Teams were encouraged to conduct patient- and family-centered rounds exclusively at bedside, except when bedside rounding was thought to be detrimental to a patient (eg, one with delirium). After an intern’s bedside presentation, which included a brief summary and details about overnight events and vital signs, the concerns of the patient, family, and nurse were shared, a focused physical examination performed, relevant data (eg, laboratory test results and imaging studies) reviewed, and the day’s plan formulated. The entire team, including the attending, was expected to have read new patients’ admission notes before rounds. Bedside rounds could thus be focused more on patient assessment and patient/family engagement and less on data transfer.

Several actions were taken to facilitate these changes. Residents, attendings, nurses, and other interdisciplinary team members participated in a series of focus groups and conferences to define workflows and share best practices for patient- and family-centered bedside rounds. Tips on bedside rounding were included in a general medicine rotation guidebook made available to residents and attendings. At the beginning of each post-intervention general medicine rotation, attendings and residents attended brief orientation sessions to review the new daily schedule, have interdisciplinary huddles, and share expectations for patient- and family-centered bedside rounds. On the general medicine units, new medical directors were hired to partner with existing nursing directors to support adoption of the workflows. Last, an interdisciplinary leadership team was formed to support the care redesign efforts. This team started meeting every 2 weeks.

Study Design

We used a pre–post analysis to study the effects of care redesign. Analysis was performed at the same time of year for 2 consecutive years to control for the stage of training and experience of the housestaff. TMA was performed by trained medical students using computer tablets linked to a customized Microsoft Access database form (Redmond, Washington). The form and the database were designed with specific buttons that, when pressed, recorded the time of particular events, such as the coming and going of each participant, the location of rounds, and the beginning and the end of rounding encounters with a patient. One research assistant using an Access entry form was able to dynamically track all events in real time, as they occurred. We collected data on 4 teams at baseline and 5 teams after the intervention. Each of the 4 baseline teams was followed for 4 consecutive weekdays—16 rounds total, April-June 2013—to capture the 4-day call cycle. Each of the 5 post-intervention teams was followed for 5 consecutive weekdays—25 rounds total, April–June 2014—to capture the 5-day cycle. (Because of technical difficulties, data from 1 rounding session were not captured.) For inclusion in the statistical analyses, TMA captured 166 on-service patients before the intervention and 304 afterward. Off-service patients, those with an attending other than the team attending, were excluded because their rounds were conducted separately.

We examined 2 primary outcomes, the proportion of time each clinical team member was present on rounds and the proportion of bedside rounding time. Secondary outcomes were round duration, rounding time per patient, and total non-patient time per rounding session (total rounding time minus total patient time).

Statistical Analysis

TMA data were organized in an Access database and analyzed with SAS Version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina). We analyzed the data by round session as well as by patient.

Data are presented as means with standard deviations, medians with interquartile ranges, and proportions, as appropriate. For analyses by round session, we used unadjusted linear regression; for patient-level analyses, we used general estimating equations to adjust for clustering of patients within each session; for nurse presence during any part of a round by patient, we used a χ2 test. Total non-patient time per round session was compared with use of patient-clustered general estimating equations using a γ distribution to account for the non-normality of the data.

RESULTS

Patient and Care Team Characteristics

Over the first year of the initiative, 85% of a team’s patients were on their assigned unit, and 87% of a unit’s patients were with the assigned team. Census numbers were 10.4 patients per general medicine team in April-June 2013 and 12.7 patients per team in April-June 2014, a 22% increase after care redesign. There were no statistically significant differences in patient characteristics, including age, sex, race, language, admission source, and comorbidity measure (Elixhauser score), between the pre-intervention and post-intervention study periods, except for a slightly higher proportion of patients admitted from home and fewer patients admitted directly from clinic (Table 1).

Primary Outcomes

Mean proportion of time the nurse was present on rounds per round session increased significantly (P < 0.001), from 24.1% to 67.8% (Figure 1A, Table 2). For individual patient encounters, the increased overall nursing presence was attributable to having more nurses on rounds and having nurses present for a larger proportion of individual rounding encounters (Figure 1B, Table 2). Nurses were present for at least some part of rounds for 53% of patients before the intervention and 93% afterward (P < 0.001). Mean proportion of round time by each of the 2 interns on each team decreased from 59.6% to 49.6% (P = 0.007).

Total bedside rounding time increased significantly ( P < 0.001), from 39.9% before the intervention to 55.8% afterward (Table 2). Meanwhile, percentage of rounding time spent on the unit but outside patient rooms decreased significantly ( P = 0.004), from 55.2% to 42.2%, as did rounding time on a unit completely different from the patient’s (4.9% before intervention, 2.0% afterward; P = 0.03). Again, patient-level results were similar (Figure 2, Table 2), but the decreased time spent on the unit, outside the patient rooms, was not significant.

Secondary Outcomes

Total rounding time decreased significantly, from a mean of 182 minutes (3.0 hours) at baseline to a mean of 146 minutes (2.4 hours) after the intervention, despite the higher post-intervention census. (When adjusted for patient census, the difference increased from 35.5 to 53.8 minutes; Table 2.) Mean rounding time per patient decreased significantly, from 14.7 minutes at baseline to 10.5 minutes after the intervention. For newly admitted patients, mean rounding time per patient decreased from 30.0 minutes before implementation to 16.3 minutes afterward. Mean rounding time also decreased, though much less, for subsequent-day patients (Table 2). For both new and existing patients, the decrease in rounding time largely was a reduction in time spent rounding outside patient rooms, with minimal impact on bedside time (Table 2). Mean time nurses were present during a patient’s rounds increased significantly, from 4.5 to 8.0 minutes (Table 2). Total nurse rounding time increased from 45.1 minutes per session to 98.8 minutes. Rounding time not related to patient discussion or evaluation decreased from 22.7 minutes per session to 13.3 minutes ( P = 0.003).

DISCUSSION

TMA of our care redesign initiative showed that this multipronged intervention, which included team regionalization, encouragement of bedside rounding with nurses, call structure changes, and attendings’ reading of admission notes before rounds, resulted in an increased proportion of rounding time spent with patients and an increased proportion of time nurses were present on rounds. Secondarily, round duration decreased even as patient census increased.

Regionalized teams have been found to improve interdisciplinary communication.1 The present study elaborates on that finding by demonstrating a dramatic increase in nursing presence on rounds, likely resulting from the unit’s use of rounding schedules and nurses’ prioritization of rounding orders, both of which were made possible by geographic co-localization. Other research has noted that one of the most significant barriers to interdisciplinary rounds is difficulty coordinating the start times of physician/nurse bedside rounding encounters. The system we have studied directly addresses this difficulty.9 Of note, nursing presence on rounds is necessary but not sufficient for true physician–nurse collaboration and effective communication,1 as reflected in a separate study of the intervention showing no significant difference in the concordance of the patient care plan between nurses and physicians before and after regionalization.12 Additional interventions may be needed to ensure that communication during bedside rounds is effective.

Our regionalized teams spent a significantly higher proportion of rounding time bedside, likely because of a cultural shift in expectations and the increased convenience of seeing patients on the team’s unit. Nevertheless, bedside time was not 100%. Structural barriers (eg, patients off-unit for dialysis) and cultural barriers likely contributed to the less than full adoption of bedside rounding. As described previously, cultural barriers to bedside rounding include trainees’ anxiety about being questioned in front of patients, the desire to freely exchange academic ideas in a conference room, and attendings’ doubts about their bedside teaching ability.1,9,13 Bedside rounds provide an important opportunity to apply the principles of patient- and family-centered care, including promotion of dignity and respect, information sharing, and collaboration. Thus, overcoming the concerns of housestaff and attendings and helping them feel prepared for bedside rounds can benefit the patient experience. More attention should be given to these practices as these types of interventions are implemented at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and elsewhere.1,13-15

Another primary concern about interdisciplinary bedside rounding is the perception that it takes more time.9 Therefore, it was important for us to measure round duration as a balancing measure to be considered for our intervention. Fortunately, we found round duration decreased with regionalization and encouragement of bedside rounding. This decrease was driven largely by a significant decrease in mean rounding time per new patient, which may be attributable at least in part to setting expectations that attendings and residents will read admission notes before rounds and that interns will summarize rather than recount information from admission notes. However, we also found rounding time decreases for subsequent-day patients, suggesting an underlying time savings. Spending a larger proportion of time bedside may therefore result in more efficient rounds. Bedside presentations can reduce redundancies, such as discussing a patient’s case outside his or her room and subsequently walking in and going over much of the same information with the patient. Our model de-emphasizes data transfer in favor of discussion of care plans. There was also a decrease in non-patient time, likely reflecting reduced transit time for regionalized teams. This decrease aligns with a recent finding that bedside rounding was at least as efficient as rounding outside the room.16

Of note, though a larger percentage of time was spent bedside after implementation of the care redesign, the absolute amount of bedside time did not change significantly. Our data showed that, even with shorter rounds, the same amount of absolute time can be spent bedside, face to face with the patient, by increasing the proportion of bedside rounding time. In other words, teams on average did not spend more time with patients, though the content and the structure of those encounters may have changed. This finding may be attributable to eliminating redundancy, forgoing the outside-the-room discussion, and thus the largest time reductions were realized there. In addition, teams incompletely adopted beside rounds, as reflected in the data. We expect that, with more complete adoption, an even larger proportion of time will be spent bedside, and absolute time bedside might increase as a result.

An unexpected result of the care redesign was that interns’ proportion of rounding time decreased after the intervention. This decrease most likely is attributable to interns’ being less likely to participate in rounds for a co-intern’s patient, and to their staying outside that patient’s room to give themselves more time to advance the care of their own patients. Before the intervention, when more rounding time was spent outside patient rooms, interns were more likely to join rounds for their co-intern’s patients because they could easily break away, as needed, to continue care of their own patients. The resident is now encouraged to use the morning huddle to identify which patients likely have the most educational value, and both interns are expected to join the bedside rounds for these patients.

This study had a few limitations. First, the pre–post design made it difficult to exclude the possibility that other temporal changes may have affected outcomes, though we did account for time-of-year effects by aligning our data-collection phases. In addition, the authors, including the director of the general medical service, are unaware of any co-interventions during the study period. Second, the multipronged intervention included care team regionalization, encouragement of bedside rounding with nurses, call structure changes (from 4 days to daily admitting), and attendings’ reading of admission notes before rounds. Thus, parsing which component(s) contributed to the results was difficult, though all the changes instituted likely were necessary for system redesign. For example, regionalization of clinicians to unit-based teams was made possible by switching to a daily admitting system.

Time that team members spent preparing for rounds was not recorded before or after the intervention. Thus, the decrease in total rounding time could have been accompanied by an increase in time spent preparing for rounds. However, admission notes were available in our electronic medical record before and after the intervention, and most residents and attendings were already reading them pre-intervention. After the intervention, pre-round note reading was more clearly defined as an expectation, and we were able to set the expectation that interns should use their presentations to summarize rather than recount information. In addition, in the post-intervention period, we did not include time spent preparing rounding orders; as already noted, however, preparation took only 5 minutes per day. Also, we did not analyze the content or the quality of the discussion on rounds, but simply recorded who was present where and when. Regarding the effect of the intervention on patient care, results were mixed. As reported in 2016, we saw no difference in frequency of adverse events with this intervention.12 However, a more sensitive measure of adverse events—used in a study on handoffs—showed our regionalization efforts had an additive effect on reducing overnight adverse events.17Researchers should now focus on the effects of care redesign on clinical outcomes, interdisciplinary care team communication, patient engagement and satisfaction, provider opinions of communication, workflow, patient care, and housestaff education. Our methodology can be used as a model to link structure, process, and outcome related to rounds and thereby better understand how best to optimize patient care and efficiency. Additional studies are needed to analyze the content of rounds and their association with patient and educational outcomes. Last, it will be important to conduct a study to see if the effects we have identified can be sustained. Such a study is already under way.

In conclusion, creating regionalized care teams and encouraging focused bedside rounds increased the proportion of bedside time and the presence of nurses on rounds. Rounds were shorter despite higher patient census. TMA revealed that regionalized care teams and bedside rounding at a large academic hospital are feasible, and are useful in establishing the necessary structures for increasing physician–nurse and provider–patient interactions.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Dr. Stan Ashley, Dr. Jacqueline Somerville, and Sheila Harris for their support of the regionalization initiative.

Disclosures

Dr. Schnipper received funding from Sanofi-aventis to conduct an investigator-initiated study to implement and evaluate a multi-faceted intervention to improve transitions of care in patients discharged home on insulin. The study was also supported by funding from the Marshall A. Wolf Medical Education Fund, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, and Dr. Stan Ashley, Chief Medical Officer, Brigham and Women’s Hospital. Some of the content of this article was orally presented at the annual meeting of the Society of Hospital Medicine; March 29-April 1, 2015; National Harbor, MD.

1. Crumlish CM, Yialamas MA, McMahon GT. Quantification of bedside teaching by an academic hospitalist group. J Hosp Med. 2009;4(5):304-307. PubMed

2. Gonzalo JD, Masters PA, Simons RJ, Chuang CH. Attending rounds and bedside case presentations: medical student and medicine resident experiences and attitudes. Teach Learn Med. 2009;21(2):105-110. PubMed

3. Elliot DL, Hickam DH. Attending rounds on in-patient units: differences between medical and non-medical services. Med Educ. 1993;27(6):503-508. PubMed

4. Payson HE, Barchas JD. A time study of medical teaching rounds. N Engl J Med. 1965;273(27):1468-1471. PubMed

5. Tremonti LP, Biddle WB. Teaching behaviors of residents and faculty members. J Med Educ. 1982;57(11):854-859. PubMed

6. Miller M, Johnson B, Greene HL, Baier M, Nowlin S. An observational study of attending rounds. J Gen Intern Med. 1992;7(6):646-648. PubMed

7. Collins GF, Cassie JM, Daggett CJ. The role of the attending physician in clinical training. J Med Educ. 1978;53(5):429-431. PubMed

8. Ward DR, Ghali WA, Graham A, Lemaire JB. A real-time locating system observes physician time-motion patterns during walk-rounds: a pilot study. BMC Med Educ. 2014;14:37. PubMed

9. Gonzalo JD, Kuperman E, Lehman E, Haidet P. Bedside interprofessional rounds: perceptions of benefits and barriers by internal medicine nursing staff, attending physicians, and housestaff physicians. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(10):646-651. PubMed

10. Stickrath C, Noble M, Prochazka A, et al. Attending rounds in the current era: what is and is not happening. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(12):1084-1089. PubMed

11. Boxer R, Vitale M, Gershanik EF, et al. 5th time’s a charm: creation of unit-based care teams in a high occupancy hospital [abstract]. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(suppl 2).

12. Mueller SK, Schnipper JL, Giannelli K, Roy CL, Boxer R. Impact of regionalized care on concordance of plan and preventable adverse events on general medicine services. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(9):620-627. PubMed

13. Chauke HL, Pattinson RC. Ward rounds—bedside or conference room? S Afr Med J. 2006;96(5):398-400. PubMed

14. Wang-Cheng RM, Barnas GP, Sigmann P, Riendl PA, Young MJ. Bedside case presentations: why patients like them but learners don’t. J Gen Intern Med. 1989;4(4):284-287. PubMed

15. Lehmann LS, Brancati FL, Chen MC, Roter D, Dobs AS. The effect of bedside case presentations on patients’ perceptions of their medical care. N Engl J Med. 1997;336(16):1150-1155. PubMed

16. Gonzalo JD, Chuang CH, Huang G, Smith C. The return of bedside rounds: an educational intervention. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(8):792-798. PubMed

17. Mueller SK, Yoon C, Schnipper JL. Association of a web-based handoff tool with rates of medical errors. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(9):1400-1402. PubMed

1. Crumlish CM, Yialamas MA, McMahon GT. Quantification of bedside teaching by an academic hospitalist group. J Hosp Med. 2009;4(5):304-307. PubMed

2. Gonzalo JD, Masters PA, Simons RJ, Chuang CH. Attending rounds and bedside case presentations: medical student and medicine resident experiences and attitudes. Teach Learn Med. 2009;21(2):105-110. PubMed

3. Elliot DL, Hickam DH. Attending rounds on in-patient units: differences between medical and non-medical services. Med Educ. 1993;27(6):503-508. PubMed

4. Payson HE, Barchas JD. A time study of medical teaching rounds. N Engl J Med. 1965;273(27):1468-1471. PubMed

5. Tremonti LP, Biddle WB. Teaching behaviors of residents and faculty members. J Med Educ. 1982;57(11):854-859. PubMed

6. Miller M, Johnson B, Greene HL, Baier M, Nowlin S. An observational study of attending rounds. J Gen Intern Med. 1992;7(6):646-648. PubMed

7. Collins GF, Cassie JM, Daggett CJ. The role of the attending physician in clinical training. J Med Educ. 1978;53(5):429-431. PubMed

8. Ward DR, Ghali WA, Graham A, Lemaire JB. A real-time locating system observes physician time-motion patterns during walk-rounds: a pilot study. BMC Med Educ. 2014;14:37. PubMed

9. Gonzalo JD, Kuperman E, Lehman E, Haidet P. Bedside interprofessional rounds: perceptions of benefits and barriers by internal medicine nursing staff, attending physicians, and housestaff physicians. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(10):646-651. PubMed

10. Stickrath C, Noble M, Prochazka A, et al. Attending rounds in the current era: what is and is not happening. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(12):1084-1089. PubMed

11. Boxer R, Vitale M, Gershanik EF, et al. 5th time’s a charm: creation of unit-based care teams in a high occupancy hospital [abstract]. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(suppl 2).

12. Mueller SK, Schnipper JL, Giannelli K, Roy CL, Boxer R. Impact of regionalized care on concordance of plan and preventable adverse events on general medicine services. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(9):620-627. PubMed

13. Chauke HL, Pattinson RC. Ward rounds—bedside or conference room? S Afr Med J. 2006;96(5):398-400. PubMed

14. Wang-Cheng RM, Barnas GP, Sigmann P, Riendl PA, Young MJ. Bedside case presentations: why patients like them but learners don’t. J Gen Intern Med. 1989;4(4):284-287. PubMed

15. Lehmann LS, Brancati FL, Chen MC, Roter D, Dobs AS. The effect of bedside case presentations on patients’ perceptions of their medical care. N Engl J Med. 1997;336(16):1150-1155. PubMed

16. Gonzalo JD, Chuang CH, Huang G, Smith C. The return of bedside rounds: an educational intervention. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(8):792-798. PubMed

17. Mueller SK, Yoon C, Schnipper JL. Association of a web-based handoff tool with rates of medical errors. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(9):1400-1402. PubMed

© 2017 Society of Hospital Medicine

Knowledge of Selected Medical Procedures

Medical procedures, an essential and highly valued part of medical education, are often undertaught and inconsistently evaluated. Hospitalists play an increasingly important role in developing the skills of resident‐learners. Alumni rate procedure skills as some of the most important skills learned during residency training,1, 2 but frequently identify training in procedural skills as having been insufficient.3, 4 For certification in internal medicine, the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) has identified a limited set of procedures in which it expects all candidates to be cognitively competent with regard to their knowledge of these procedures. Although active participation in procedures is recommended for certification in internal medicine, the demonstration of procedural proficiency is not required.5

Resident competence in performing procedures remains highly variable and procedural complications can be a source of morbidity and mortality.2, 6, 7 A validated tool for the assessment of procedure related knowledge is currently lacking. In existing standardized tests, including the in‐training examination (ITE) and ABIM certification examination, only a fraction of questions pertain to medical procedures. The necessity for a specifically designed, standardized instrument that can objectively measure procedure related knowledge has been highlighted by studies that have demonstrated that there is little correlation between the rate of procedure‐related complications and ABIM/ITE scores.8 A validated tool to assess the knowledge of residents in selected medical procedures could serve to assess the readiness of residents to begin supervised practice and form part of a proficiency assessment.

In this study we aimed to develop a valid and reliable test of procedural knowledge in 3 procedures associated with potentially serious complications.

Methods

Placement of an arterial line, central venous catheter and thoracentesis were selected as the focus for test development. Using the National Board of Medical Examiners question development guidelines, multiple‐choice questions were developed to test residents on specific points of a prepared curriculum. Questions were designed to test the essential cognitive aspects of medical procedures, including indications, contraindications, and the management of complications, with an emphasis on the elements that were considered by a panel of experts to be frequently misunderstood. Questions were written by faculty trained in question writing (G.M.) and assessed for clarity by other members of faculty. Content evidence of the 36‐item examination (12 questions per procedure) was established by a panel of 4 critical care specialists with expertise in medical education. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at all sites.

Item performance characteristics were evaluated by administering the test online to a series of 30 trainees and specialty clinicians. Postadministration interviews with the critical care experts were performed to determine whether test questions were clear and appropriate for residents. Following initial testing, 4 test items with the lowest discrimination according to a point‐biserial correlation (Integrity; Castle Rock Research, Canada) were deleted from the test. The resulting 32‐item test contained items of varying difficulty to allow for effective discrimination between examinees (Appendix 1).

The test was then administered to residents beginning rotations in either the medical intensive care unit or in the coronary care unit at 4 medical centers in Massachusetts (Brigham and Women's Hospital; Massachusetts General Hospital; Faulkner Hospital; and North Shore Medical Center). In addition to completing the on‐line, self‐administered examination, participants provided baseline data including year of residency training, anticipated career path, and the number of prior procedures performed. On a 5‐point Likert scale participants estimated their self‐perceived confidence at performing the procedure (with and without supervision) and supervising each of the procedures. Residents were invited to complete a second test before the end of their rotation (2‐4 weeks after the initial test) in order to assess test‐retest reliability. Answers were made available only after the conclusion of the study.

Reliability of the 32‐item instrument was measured by Cronbach's analysis; a value of 0.6 is considered adequate and values of 0.7 or higher indicate good reliability. Pearson's correlation (Pearson's r) was used to compute test‐retest reliability. Univariate analyses were used to assess the association of the demographic variables with the test scores. Comparison of test scores between groups was made using a t test/Wilcoxon rank sum (2 groups) and analysis of variance (ANOVA)/Kruskal‐Wallis (3 or more groups). The associations of number of prior procedures attempted and self‐reported confidence with test scores was explored using Spearman's correlation. Inferences were made at the 0.05 level of significance, using 2‐tailed tests. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 15.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL).

Results

Of the 192 internal medicine residents who consented to participate in the study between February and June 2006, 188 completed the initial and repeat test. Subject characteristics are detailed in Table 1.

| Number (%) | |

|---|---|

| Total residents | 192 |

| Males | 113 (59) |

| Year of residency training | |

| First | 101 (52) |

| Second | 64 (33) |

| Third/fourth | 27 (14) |

| Anticipated career path | |

| General medicine/primary care | 26 (14) |

| Critical care | 47 (24) |

| Medical subspecialties | 54 (28) |

| Undecided/other | 65 (34) |