User login

new research suggests.

Results from a cohort study of more than 4.2 million individuals showed that offspring of mothers with PIDs had a 17% increased risk for a psychiatric disorder and a 20% increased risk for suicidal behavior, compared with their peers with mothers who did not have PIDs.

The risk was more pronounced in offspring of mothers with both PIDs and autoimmune diseases. These risks remained after strictly controlling for different covariates, such as the parents’ psychiatric history, offspring PIDs, and offspring autoimmune diseases.

The investigators, led by Josef Isung, MD, PhD, Centre for Psychiatry Research, department of clinical neuroscience, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, noted that they could not “pinpoint a precise causal mechanism” underlying these findings.

Still, “the results add to the existing literature suggesting that the intrauterine immune environment may have implications for fetal neurodevelopment and that a compromised maternal immune system during pregnancy may be a risk factor for psychiatric disorders and suicidal behavior in their offspring in the long term,” they wrote.

The findings were published online in JAMA Psychiatry.

‘Natural experiment’

Maternal immune activation (MIA) is “an overarching term for aberrant and disrupted immune activity in the mother during gestation [and] has long been of interest in relation to adverse health outcomes in the offspring,” Dr. Isung noted.

“In relation to negative psychiatric outcomes, there is an abundance of preclinical evidence that has shown a negative impact on offspring secondary to MIA. And in humans, there are several observational studies supporting this link,” he said in an interview.

Dr. Isung added that PIDs are “rare conditions” known to be associated with repeated infections and high rates of autoimmune diseases, causing substantial disability.

“PIDs represent an interesting ‘natural experiment’ for researchers to understand more about the association between immune system dysfunctions and mental health,” he said.

Dr. Isung’s group previously showed that individuals with PIDs have increased odds of psychiatric disorders and suicidal behavior. The link was more pronounced in women with PIDs – and was even more pronounced in those with both PIDs and autoimmune diseases.

In the current study, “we wanted to see whether offspring of individuals were differentially at risk of psychiatric disorders and suicidal behavior, depending on being offspring of mothers or fathers with PIDs,” Dr. Isung said.

“Our hypothesis was that mothers with PIDs would have an increased risk of having offspring with neuropsychiatric outcomes, and that this risk could be due to MIA,” he added.

The researchers turned to Swedish nationwide health and administrative registers. They analyzed data on all individuals with diagnoses of PIDs identified between 1973 and 2013. Offspring born prior to 2003 were included, and parent-offspring pairs in which both parents had a history of PIDs were excluded.

The final study sample consisted of 4,294,169 offspring (51.4% boys). Of these participants, 7,270 (0.17%) had a parent with PIDs.

The researchers identified lifetime records of 10 psychiatric disorders: obsessive-compulsive disorder, ADHD, autism spectrum disorders, schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders, bipolar disorders, major depressive disorder and other mood disorders, anxiety and stress-related disorders, eating disorders, substance use disorders, and Tourette syndrome and chronic tic disorders.

The investigators included parental birth year, psychopathology, suicide attempts, suicide deaths, and autoimmune diseases as covariates, as well as offsprings’ birth year and gender.

Elucidation needed

Results showed that, of the 4,676 offspring of mothers with PID, 17.1% had a psychiatric disorder versus 12.7% of offspring of mothers without PIDs. This translated “into a 17% increased risk for offspring of mothers with PIDs in the fully adjusted model,” the investigators reported.

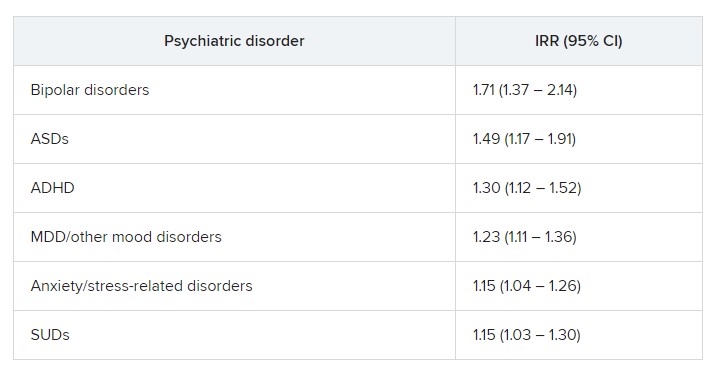

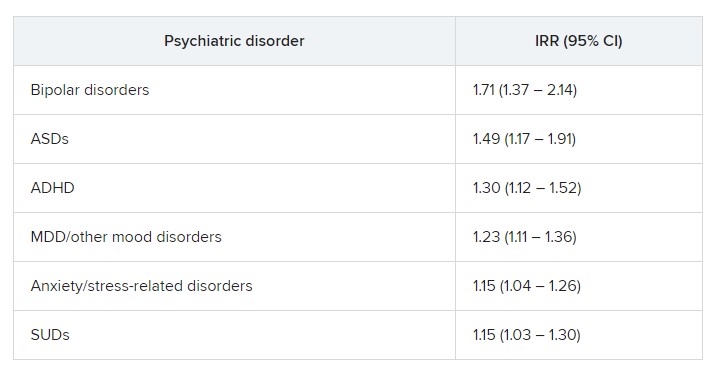

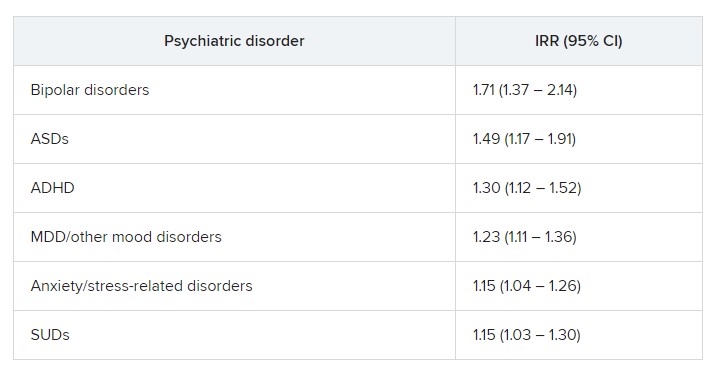

The risk was even higher for offspring of mothers who had not only PIDs but also one of six of the individual psychiatric disorders, with incident rate ratios ranging from 1.15 to 1.71.

“In fully adjusted models, offspring of mothers with PIDs had an increased risk of any psychiatric disorder, while no such risks were observed in offspring of fathers with PIDs” (IRR, 1.17 vs. 1.03; P < .001), the researchers reported.

A higher risk for suicidal behavior was also observed among offspring of mothers with PIDS, in contrast to those of fathers with PIDs (IRR, 1.2 vs. 1.1; P = .01).

The greatest risk for any psychiatric disorder, as well as suicidal behavior, was found in offspring of mothers who had both PIDs and autoimmune diseases (IRRs, 1.24 and 1.44, respectively).

“The results could be seen as substantiating the hypothesis that immune disruption may be important in the pathophysiology of psychiatric disorders and suicidal behavior,” Dr. Isung said.

“Furthermore, the fact that only offspring of mothers and not offspring of fathers with PIDs had this association would align with our hypothesis that MIA is of importance,” he added.

However, he noted that “the specific mechanisms are most likely multifactorial and remain to be elucidated.”

Important piece of the puzzle?

In a comment, Michael Eriksen Benros, MD, PhD, professor of immunopsychiatry, department of immunology and microbiology, health, and medical sciences, University of Copenhagen, said this was a “high-quality study” that used a “rich data source.”

Dr. Benros, who is also head of research (biological and precision psychiatry) at the Copenhagen Research Centre for Mental Health, Copenhagen University Hospital, was not involved with the current study.

He noted that prior studies, including some conducted by his own group, have shown that maternal infections overall did not seem to be “specifically linked to mental disorders in the offspring.”

However, “specific maternal infections or specific brain-reactive antibodies during the pregnancy period have been shown to be associated with neurodevelopmental outcomes among the children,” such as intellectual disability, he said.

Regarding direct clinical implications of the study, “it is important to note that the increased risk of psychiatric disorders and suicidality in the offspring of mothers with PID were small,” Dr. Benros said.

“However, it adds an important part to the scientific puzzle regarding the role of maternal immune activation during pregnancy and the risk of mental disorders,” he added.

The study was funded by the Söderström König Foundation and the Fredrik and Ingrid Thuring Foundation. Neither Dr. Isung nor Dr. Benros reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

new research suggests.

Results from a cohort study of more than 4.2 million individuals showed that offspring of mothers with PIDs had a 17% increased risk for a psychiatric disorder and a 20% increased risk for suicidal behavior, compared with their peers with mothers who did not have PIDs.

The risk was more pronounced in offspring of mothers with both PIDs and autoimmune diseases. These risks remained after strictly controlling for different covariates, such as the parents’ psychiatric history, offspring PIDs, and offspring autoimmune diseases.

The investigators, led by Josef Isung, MD, PhD, Centre for Psychiatry Research, department of clinical neuroscience, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, noted that they could not “pinpoint a precise causal mechanism” underlying these findings.

Still, “the results add to the existing literature suggesting that the intrauterine immune environment may have implications for fetal neurodevelopment and that a compromised maternal immune system during pregnancy may be a risk factor for psychiatric disorders and suicidal behavior in their offspring in the long term,” they wrote.

The findings were published online in JAMA Psychiatry.

‘Natural experiment’

Maternal immune activation (MIA) is “an overarching term for aberrant and disrupted immune activity in the mother during gestation [and] has long been of interest in relation to adverse health outcomes in the offspring,” Dr. Isung noted.

“In relation to negative psychiatric outcomes, there is an abundance of preclinical evidence that has shown a negative impact on offspring secondary to MIA. And in humans, there are several observational studies supporting this link,” he said in an interview.

Dr. Isung added that PIDs are “rare conditions” known to be associated with repeated infections and high rates of autoimmune diseases, causing substantial disability.

“PIDs represent an interesting ‘natural experiment’ for researchers to understand more about the association between immune system dysfunctions and mental health,” he said.

Dr. Isung’s group previously showed that individuals with PIDs have increased odds of psychiatric disorders and suicidal behavior. The link was more pronounced in women with PIDs – and was even more pronounced in those with both PIDs and autoimmune diseases.

In the current study, “we wanted to see whether offspring of individuals were differentially at risk of psychiatric disorders and suicidal behavior, depending on being offspring of mothers or fathers with PIDs,” Dr. Isung said.

“Our hypothesis was that mothers with PIDs would have an increased risk of having offspring with neuropsychiatric outcomes, and that this risk could be due to MIA,” he added.

The researchers turned to Swedish nationwide health and administrative registers. They analyzed data on all individuals with diagnoses of PIDs identified between 1973 and 2013. Offspring born prior to 2003 were included, and parent-offspring pairs in which both parents had a history of PIDs were excluded.

The final study sample consisted of 4,294,169 offspring (51.4% boys). Of these participants, 7,270 (0.17%) had a parent with PIDs.

The researchers identified lifetime records of 10 psychiatric disorders: obsessive-compulsive disorder, ADHD, autism spectrum disorders, schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders, bipolar disorders, major depressive disorder and other mood disorders, anxiety and stress-related disorders, eating disorders, substance use disorders, and Tourette syndrome and chronic tic disorders.

The investigators included parental birth year, psychopathology, suicide attempts, suicide deaths, and autoimmune diseases as covariates, as well as offsprings’ birth year and gender.

Elucidation needed

Results showed that, of the 4,676 offspring of mothers with PID, 17.1% had a psychiatric disorder versus 12.7% of offspring of mothers without PIDs. This translated “into a 17% increased risk for offspring of mothers with PIDs in the fully adjusted model,” the investigators reported.

The risk was even higher for offspring of mothers who had not only PIDs but also one of six of the individual psychiatric disorders, with incident rate ratios ranging from 1.15 to 1.71.

“In fully adjusted models, offspring of mothers with PIDs had an increased risk of any psychiatric disorder, while no such risks were observed in offspring of fathers with PIDs” (IRR, 1.17 vs. 1.03; P < .001), the researchers reported.

A higher risk for suicidal behavior was also observed among offspring of mothers with PIDS, in contrast to those of fathers with PIDs (IRR, 1.2 vs. 1.1; P = .01).

The greatest risk for any psychiatric disorder, as well as suicidal behavior, was found in offspring of mothers who had both PIDs and autoimmune diseases (IRRs, 1.24 and 1.44, respectively).

“The results could be seen as substantiating the hypothesis that immune disruption may be important in the pathophysiology of psychiatric disorders and suicidal behavior,” Dr. Isung said.

“Furthermore, the fact that only offspring of mothers and not offspring of fathers with PIDs had this association would align with our hypothesis that MIA is of importance,” he added.

However, he noted that “the specific mechanisms are most likely multifactorial and remain to be elucidated.”

Important piece of the puzzle?

In a comment, Michael Eriksen Benros, MD, PhD, professor of immunopsychiatry, department of immunology and microbiology, health, and medical sciences, University of Copenhagen, said this was a “high-quality study” that used a “rich data source.”

Dr. Benros, who is also head of research (biological and precision psychiatry) at the Copenhagen Research Centre for Mental Health, Copenhagen University Hospital, was not involved with the current study.

He noted that prior studies, including some conducted by his own group, have shown that maternal infections overall did not seem to be “specifically linked to mental disorders in the offspring.”

However, “specific maternal infections or specific brain-reactive antibodies during the pregnancy period have been shown to be associated with neurodevelopmental outcomes among the children,” such as intellectual disability, he said.

Regarding direct clinical implications of the study, “it is important to note that the increased risk of psychiatric disorders and suicidality in the offspring of mothers with PID were small,” Dr. Benros said.

“However, it adds an important part to the scientific puzzle regarding the role of maternal immune activation during pregnancy and the risk of mental disorders,” he added.

The study was funded by the Söderström König Foundation and the Fredrik and Ingrid Thuring Foundation. Neither Dr. Isung nor Dr. Benros reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

new research suggests.

Results from a cohort study of more than 4.2 million individuals showed that offspring of mothers with PIDs had a 17% increased risk for a psychiatric disorder and a 20% increased risk for suicidal behavior, compared with their peers with mothers who did not have PIDs.

The risk was more pronounced in offspring of mothers with both PIDs and autoimmune diseases. These risks remained after strictly controlling for different covariates, such as the parents’ psychiatric history, offspring PIDs, and offspring autoimmune diseases.

The investigators, led by Josef Isung, MD, PhD, Centre for Psychiatry Research, department of clinical neuroscience, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, noted that they could not “pinpoint a precise causal mechanism” underlying these findings.

Still, “the results add to the existing literature suggesting that the intrauterine immune environment may have implications for fetal neurodevelopment and that a compromised maternal immune system during pregnancy may be a risk factor for psychiatric disorders and suicidal behavior in their offspring in the long term,” they wrote.

The findings were published online in JAMA Psychiatry.

‘Natural experiment’

Maternal immune activation (MIA) is “an overarching term for aberrant and disrupted immune activity in the mother during gestation [and] has long been of interest in relation to adverse health outcomes in the offspring,” Dr. Isung noted.

“In relation to negative psychiatric outcomes, there is an abundance of preclinical evidence that has shown a negative impact on offspring secondary to MIA. And in humans, there are several observational studies supporting this link,” he said in an interview.

Dr. Isung added that PIDs are “rare conditions” known to be associated with repeated infections and high rates of autoimmune diseases, causing substantial disability.

“PIDs represent an interesting ‘natural experiment’ for researchers to understand more about the association between immune system dysfunctions and mental health,” he said.

Dr. Isung’s group previously showed that individuals with PIDs have increased odds of psychiatric disorders and suicidal behavior. The link was more pronounced in women with PIDs – and was even more pronounced in those with both PIDs and autoimmune diseases.

In the current study, “we wanted to see whether offspring of individuals were differentially at risk of psychiatric disorders and suicidal behavior, depending on being offspring of mothers or fathers with PIDs,” Dr. Isung said.

“Our hypothesis was that mothers with PIDs would have an increased risk of having offspring with neuropsychiatric outcomes, and that this risk could be due to MIA,” he added.

The researchers turned to Swedish nationwide health and administrative registers. They analyzed data on all individuals with diagnoses of PIDs identified between 1973 and 2013. Offspring born prior to 2003 were included, and parent-offspring pairs in which both parents had a history of PIDs were excluded.

The final study sample consisted of 4,294,169 offspring (51.4% boys). Of these participants, 7,270 (0.17%) had a parent with PIDs.

The researchers identified lifetime records of 10 psychiatric disorders: obsessive-compulsive disorder, ADHD, autism spectrum disorders, schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders, bipolar disorders, major depressive disorder and other mood disorders, anxiety and stress-related disorders, eating disorders, substance use disorders, and Tourette syndrome and chronic tic disorders.

The investigators included parental birth year, psychopathology, suicide attempts, suicide deaths, and autoimmune diseases as covariates, as well as offsprings’ birth year and gender.

Elucidation needed

Results showed that, of the 4,676 offspring of mothers with PID, 17.1% had a psychiatric disorder versus 12.7% of offspring of mothers without PIDs. This translated “into a 17% increased risk for offspring of mothers with PIDs in the fully adjusted model,” the investigators reported.

The risk was even higher for offspring of mothers who had not only PIDs but also one of six of the individual psychiatric disorders, with incident rate ratios ranging from 1.15 to 1.71.

“In fully adjusted models, offspring of mothers with PIDs had an increased risk of any psychiatric disorder, while no such risks were observed in offspring of fathers with PIDs” (IRR, 1.17 vs. 1.03; P < .001), the researchers reported.

A higher risk for suicidal behavior was also observed among offspring of mothers with PIDS, in contrast to those of fathers with PIDs (IRR, 1.2 vs. 1.1; P = .01).

The greatest risk for any psychiatric disorder, as well as suicidal behavior, was found in offspring of mothers who had both PIDs and autoimmune diseases (IRRs, 1.24 and 1.44, respectively).

“The results could be seen as substantiating the hypothesis that immune disruption may be important in the pathophysiology of psychiatric disorders and suicidal behavior,” Dr. Isung said.

“Furthermore, the fact that only offspring of mothers and not offspring of fathers with PIDs had this association would align with our hypothesis that MIA is of importance,” he added.

However, he noted that “the specific mechanisms are most likely multifactorial and remain to be elucidated.”

Important piece of the puzzle?

In a comment, Michael Eriksen Benros, MD, PhD, professor of immunopsychiatry, department of immunology and microbiology, health, and medical sciences, University of Copenhagen, said this was a “high-quality study” that used a “rich data source.”

Dr. Benros, who is also head of research (biological and precision psychiatry) at the Copenhagen Research Centre for Mental Health, Copenhagen University Hospital, was not involved with the current study.

He noted that prior studies, including some conducted by his own group, have shown that maternal infections overall did not seem to be “specifically linked to mental disorders in the offspring.”

However, “specific maternal infections or specific brain-reactive antibodies during the pregnancy period have been shown to be associated with neurodevelopmental outcomes among the children,” such as intellectual disability, he said.

Regarding direct clinical implications of the study, “it is important to note that the increased risk of psychiatric disorders and suicidality in the offspring of mothers with PID were small,” Dr. Benros said.

“However, it adds an important part to the scientific puzzle regarding the role of maternal immune activation during pregnancy and the risk of mental disorders,” he added.

The study was funded by the Söderström König Foundation and the Fredrik and Ingrid Thuring Foundation. Neither Dr. Isung nor Dr. Benros reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JAMA PSYCHIATRY