User login

Mrs. K, an 81-year-old golf-enthusiast admitted with congestive heart failure, now refuses to walk and complains of ankle pain. When you see her, she refuses to let even a bedsheet near her left ankle, and she claims that you did this to her.

Unfortunately, she’s probably right. Mrs. K also has a history of podagra, and she developed an acute gouty monoarthritis after receiving treatment with diuretics and aspirin. Gout—along with the other causes of inpatient acute monoarthritis (pseudogout, septic arthritis, and trauma)—are increasingly common diagnoses in the geriatric patient population. Because the elderly are uniquely predisposed to losing functional independence following an acute attack, making a timely diagnosis is particularly important in this age group. And though the patient’s clinical features may point toward an etiology, making the correct diagnosis ultimately depends on the results of the joint tap.

Gout

Gout occurs in patients with high serum levels of uric acid, though not all hyperuricemic patients develop gout. Among elderly hospitalized patients with hyperuricemia, approximately 65% have significant renal impairment, and others have advanced hypertension, coronary artery disease, and congestive heart failure. Over time, high serum uric acid levels may lead to the deposition of monosodium urate crystals in the joints; these lesions are the precursors of a gouty attack.

Gouty attacks occur when crystal deposits become inflamed. The inflammation may be triggered by a medication-induced change in uric acid concentration or by a medical condition, including acute illness, trauma, surgery, and dehydration. (See Table 1, p.18.) Though some elderly patients with acute gouty arthritis will manifest confusion or a sudden change in ambulatory status, most will present with a monoarthritis and a rise in temperature. Gout is suspected clinically when the first metatarsal phalangeal joint is involved (podagra), but other commonly involved joints include the ankle and the knee. Uric acid levels in the blood are usually elevated but can also temporarily normalize or even dip low during attacks. An X-ray of the involved joint may be normal or may already show the characteristic erosive lesion of gout, the “overhanging edge.”

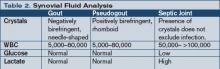

Making the correct diagnosis is dependent upon visualizing intracellular, needle-shaped, negatively birefringent crystals in the synovial fluid. After the fluid is removed from the affected joint, it should be examined under polarized light within two hours; if more time is needed, the fluid can be refrigerated for up to 12 hours. Co-infection of a gouty joint has been described in the elderly population, and the synovial fluid should be sent to the laboratory for a cell count, Gram’s stain, and culture, as well as glucose and lactate levels. (See Table 2, below.)

Direct in-hospital treatment of gout toward alleviating the current attack, preventing future attacks, and providing appropriate antibiotic coverage in suspected co-infected cases until joint culture results are finalized. Treatment options for the acute attack include NSAIDs and corticosteroids—either oral or intra-articular. Hourly oral colchicine is not a good option for an elderly patient because the diarrhea that ensues is particularly disruptive. Nor is IV colchicine a good option thanks to its side-effect profile that renders it unusable in patients with reduced renal function. The treatment of hyperuricemia with allopurinol should not be undertaken during the acute attack because any change in the serum uric acid concentration will serve only to exacerbate the current inflammation.

Anti-inflammatory doses of NSAIDs are effective and will shorten the duration of symptoms substantially. Seven to 10 days of indomethacin at a dose of 50 mg taken orally three times daily is the traditional choice, and though it is generally conceded that ibuprofen and naproxen also work well, no comparative trials have been performed. Elderly patients are at increased risk for adverse effects from NSAIDs, particularly those patients with severely reduced renal function, gastropathy, asthma, congestive heart failure, or other intravascularly depleted states. Gastric mucosal protection, using proton-pump inhibitors, and careful monitoring of fluid status, renal function, and mental status are of particular concern in this population.

Because recent research indicates that COX-2 inhibitors have thrombotic potential and are contraindicated in patients at high risk for cardiovascular events or stroke, the extent to which they can be used in an elderly patient with an acute gouty attack is limited. A traditional NSAID in combination with a proton-pump inhibitor may be as effective as a COX-2 inhibitor in reducing the risk of gastroduodenal toxicity, however.

Corticosteroids—given either orally or intra-articularly—are an appropriate treatment for patients who can’t tolerate an NSAID. As long as a septic joint has been excluded, an intra-articular injection of 40–80 mg triamcinolone acetonide or 40 mg of methylprednisolone acetate will result in major improvement within 24 hours for most patients. Another option is a seven- to 10-day course of oral prednisone, starting with 40 mg on day one and reducing the dosage by 5 mg/day. Elderly patients taking oral prednisone should also receive adequate calcium, vitamin D, and a proton pump inhibitor for gastrointestinal protection, as well as close monitoring of blood pressure, glucose, and mental status.

If a patient has a history of frequent attacks or tophi, has a serum uric acid level higher than 12 mg/dl, or is consistently receiving high doses of diuretics, that person is at high risk for subsequent attacks and should receive prophylactic treatment with either a low-dose daily NSAID or a renally dosed oral colchicine.

Pseudogout

Pseudogout is the articular manifestation of calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate (CPPD) deposition, and this process is associated with aging as well as with various endocrinopathies, the most common of which is hyperparathyroidism. (See Table 3, below.) The shedding of CPPD crystals initiates an inflammatory process, and these crystals invoke an inflammatory response in much the same manner as uric acid crystals.

While the precipitants of a pseudogout attack are less well defined than those of gout, dehydration and joint surgery have both been identified as predisposing factors. The acute monoarticular pain and swelling (the knee is most common, followed by the ankle and then any other synovial joint) that ensues usually has a more insidious onset, and an X-ray may show chondrocalcinosis within the joint space. The diagnosis is confirmed by the demonstration of intracellular CPPD crystals in the aspirated joint fluid. Though less easily seen than monosodium urate crystals, rhomboidal crystals that display weakly positive birefringence under polarized light will be revealed with careful observation. Vitally important to the diagnosis of any crystal-associated arthritis is the exclusion of septic arthritis. To this end, conduct synovial fluid and blood cultures even if the suspicion of sepsis is low.

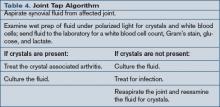

Treatment goals for pseudogout center on the abatement of the current arthritis and the exclusion of an infected joint or a concurrent metabolic syndrome. NSAIDs are the mainstay of therapy for the management of pseudogout; they are prescribed in anti-inflammatory doses similar to those used in the treatment of gout. Corticosteroids can also be used, particularly an intra-articular injection, as long as infection has been excluded. As with any crystal arthropathy, a septic joint should be considered and treated in high-risk patients even before the results of the joint fluid cultures are available. (See Table 4, above.)

Septic Arthritis

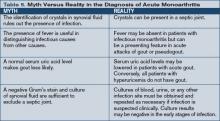

Even with timely antibacterial treatment, an elderly patient with a septic joint has a 7% to 32% mortality rate. Staphylococcus and Streptococcus are the most commonly cultured pathogens, but consider E. coli, Pseudomonas, and Klebsiella species in patients with diabetes mellitus, malignancy, or other debilitating chronic syndromes; less common agents include tuberculosis and gonococcus. Fever may be present, but a recent study revealed that fewer than 60% of geriatric patients with septic arthritis presented with a febrile illness. Thus, systemic features are not reliable enough to warrant making or excluding the diagnosis of septic arthritis without examination of the synovial fluid. (See Table 5, below.)

Send synovial fluid for leukocyte count, Gram’s stain, and culture in all suspected cases, and several studies suggest that the diagnostic yield may be improved with direct inoculation of fluid into blood culture vials or isolator tubes. Synovial fluid will also show very low glucose (less than 25% of simultaneous plasma glucose) and very high lactate (greater than 10 mm/l) in the untreated bacterial septic joint.

Treatment of a septic joint includes both appropriate antimicrobial therapy and joint drainage. Three weeks of parenteral antimicrobial therapy directed against the isolated pathogen is usually sufficient once the affected joint has been drained. Surgical drainage is indicated in joints—like the hip—that are difficult to aspirate or monitor. Other indications include pus in the synovial fluid, spread of infection to the soft tissues, or an inadequate clinical response to appropriate antibiotics after five to seven days. Otherwise, daily aspiration is the treatment of choice for an uncomplicated infected joint. Additionally, as is true in any acute monoarthritis, bed rest and optimal joint positioning are required to prevent the occurrence of joint deformation and harmful contractures. TH

Dr. Landis is a rheumatologist and a freelance writer.

Special thanks to Bradley Flansbaum, MD, for his assistance with this article.

References

- Tenenbaum J. Inflammatory musculoskeletal conditions in older adults. Geriatr Aging. 2005;8(3):14-17.

- Bieber JD, Terkeltaub RA. Gout: on the brink of novel therapeutic options for an ancient disease. Arthritis Rheum. 2004 Aug;50(8):2400-2414.

- Terkeltaub RA. Clinical practice. Gout. N Engl J Med. 2003 Oct 23;349(17):1647-1655.

- Leirisalo-Repo M. Early arthritis and infection. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2005 Jul;17(4):433-439.

- Siva C, Velazquez C, Mody A, et al. Diagnosing acute monoarthritis in adults: a practical approach for the family physician. Am Fam Physician. 2003 Jul 1;68(1):83-90.

Mrs. K, an 81-year-old golf-enthusiast admitted with congestive heart failure, now refuses to walk and complains of ankle pain. When you see her, she refuses to let even a bedsheet near her left ankle, and she claims that you did this to her.

Unfortunately, she’s probably right. Mrs. K also has a history of podagra, and she developed an acute gouty monoarthritis after receiving treatment with diuretics and aspirin. Gout—along with the other causes of inpatient acute monoarthritis (pseudogout, septic arthritis, and trauma)—are increasingly common diagnoses in the geriatric patient population. Because the elderly are uniquely predisposed to losing functional independence following an acute attack, making a timely diagnosis is particularly important in this age group. And though the patient’s clinical features may point toward an etiology, making the correct diagnosis ultimately depends on the results of the joint tap.

Gout

Gout occurs in patients with high serum levels of uric acid, though not all hyperuricemic patients develop gout. Among elderly hospitalized patients with hyperuricemia, approximately 65% have significant renal impairment, and others have advanced hypertension, coronary artery disease, and congestive heart failure. Over time, high serum uric acid levels may lead to the deposition of monosodium urate crystals in the joints; these lesions are the precursors of a gouty attack.

Gouty attacks occur when crystal deposits become inflamed. The inflammation may be triggered by a medication-induced change in uric acid concentration or by a medical condition, including acute illness, trauma, surgery, and dehydration. (See Table 1, p.18.) Though some elderly patients with acute gouty arthritis will manifest confusion or a sudden change in ambulatory status, most will present with a monoarthritis and a rise in temperature. Gout is suspected clinically when the first metatarsal phalangeal joint is involved (podagra), but other commonly involved joints include the ankle and the knee. Uric acid levels in the blood are usually elevated but can also temporarily normalize or even dip low during attacks. An X-ray of the involved joint may be normal or may already show the characteristic erosive lesion of gout, the “overhanging edge.”

Making the correct diagnosis is dependent upon visualizing intracellular, needle-shaped, negatively birefringent crystals in the synovial fluid. After the fluid is removed from the affected joint, it should be examined under polarized light within two hours; if more time is needed, the fluid can be refrigerated for up to 12 hours. Co-infection of a gouty joint has been described in the elderly population, and the synovial fluid should be sent to the laboratory for a cell count, Gram’s stain, and culture, as well as glucose and lactate levels. (See Table 2, below.)

Direct in-hospital treatment of gout toward alleviating the current attack, preventing future attacks, and providing appropriate antibiotic coverage in suspected co-infected cases until joint culture results are finalized. Treatment options for the acute attack include NSAIDs and corticosteroids—either oral or intra-articular. Hourly oral colchicine is not a good option for an elderly patient because the diarrhea that ensues is particularly disruptive. Nor is IV colchicine a good option thanks to its side-effect profile that renders it unusable in patients with reduced renal function. The treatment of hyperuricemia with allopurinol should not be undertaken during the acute attack because any change in the serum uric acid concentration will serve only to exacerbate the current inflammation.

Anti-inflammatory doses of NSAIDs are effective and will shorten the duration of symptoms substantially. Seven to 10 days of indomethacin at a dose of 50 mg taken orally three times daily is the traditional choice, and though it is generally conceded that ibuprofen and naproxen also work well, no comparative trials have been performed. Elderly patients are at increased risk for adverse effects from NSAIDs, particularly those patients with severely reduced renal function, gastropathy, asthma, congestive heart failure, or other intravascularly depleted states. Gastric mucosal protection, using proton-pump inhibitors, and careful monitoring of fluid status, renal function, and mental status are of particular concern in this population.

Because recent research indicates that COX-2 inhibitors have thrombotic potential and are contraindicated in patients at high risk for cardiovascular events or stroke, the extent to which they can be used in an elderly patient with an acute gouty attack is limited. A traditional NSAID in combination with a proton-pump inhibitor may be as effective as a COX-2 inhibitor in reducing the risk of gastroduodenal toxicity, however.

Corticosteroids—given either orally or intra-articularly—are an appropriate treatment for patients who can’t tolerate an NSAID. As long as a septic joint has been excluded, an intra-articular injection of 40–80 mg triamcinolone acetonide or 40 mg of methylprednisolone acetate will result in major improvement within 24 hours for most patients. Another option is a seven- to 10-day course of oral prednisone, starting with 40 mg on day one and reducing the dosage by 5 mg/day. Elderly patients taking oral prednisone should also receive adequate calcium, vitamin D, and a proton pump inhibitor for gastrointestinal protection, as well as close monitoring of blood pressure, glucose, and mental status.

If a patient has a history of frequent attacks or tophi, has a serum uric acid level higher than 12 mg/dl, or is consistently receiving high doses of diuretics, that person is at high risk for subsequent attacks and should receive prophylactic treatment with either a low-dose daily NSAID or a renally dosed oral colchicine.

Pseudogout

Pseudogout is the articular manifestation of calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate (CPPD) deposition, and this process is associated with aging as well as with various endocrinopathies, the most common of which is hyperparathyroidism. (See Table 3, below.) The shedding of CPPD crystals initiates an inflammatory process, and these crystals invoke an inflammatory response in much the same manner as uric acid crystals.

While the precipitants of a pseudogout attack are less well defined than those of gout, dehydration and joint surgery have both been identified as predisposing factors. The acute monoarticular pain and swelling (the knee is most common, followed by the ankle and then any other synovial joint) that ensues usually has a more insidious onset, and an X-ray may show chondrocalcinosis within the joint space. The diagnosis is confirmed by the demonstration of intracellular CPPD crystals in the aspirated joint fluid. Though less easily seen than monosodium urate crystals, rhomboidal crystals that display weakly positive birefringence under polarized light will be revealed with careful observation. Vitally important to the diagnosis of any crystal-associated arthritis is the exclusion of septic arthritis. To this end, conduct synovial fluid and blood cultures even if the suspicion of sepsis is low.

Treatment goals for pseudogout center on the abatement of the current arthritis and the exclusion of an infected joint or a concurrent metabolic syndrome. NSAIDs are the mainstay of therapy for the management of pseudogout; they are prescribed in anti-inflammatory doses similar to those used in the treatment of gout. Corticosteroids can also be used, particularly an intra-articular injection, as long as infection has been excluded. As with any crystal arthropathy, a septic joint should be considered and treated in high-risk patients even before the results of the joint fluid cultures are available. (See Table 4, above.)

Septic Arthritis

Even with timely antibacterial treatment, an elderly patient with a septic joint has a 7% to 32% mortality rate. Staphylococcus and Streptococcus are the most commonly cultured pathogens, but consider E. coli, Pseudomonas, and Klebsiella species in patients with diabetes mellitus, malignancy, or other debilitating chronic syndromes; less common agents include tuberculosis and gonococcus. Fever may be present, but a recent study revealed that fewer than 60% of geriatric patients with septic arthritis presented with a febrile illness. Thus, systemic features are not reliable enough to warrant making or excluding the diagnosis of septic arthritis without examination of the synovial fluid. (See Table 5, below.)

Send synovial fluid for leukocyte count, Gram’s stain, and culture in all suspected cases, and several studies suggest that the diagnostic yield may be improved with direct inoculation of fluid into blood culture vials or isolator tubes. Synovial fluid will also show very low glucose (less than 25% of simultaneous plasma glucose) and very high lactate (greater than 10 mm/l) in the untreated bacterial septic joint.

Treatment of a septic joint includes both appropriate antimicrobial therapy and joint drainage. Three weeks of parenteral antimicrobial therapy directed against the isolated pathogen is usually sufficient once the affected joint has been drained. Surgical drainage is indicated in joints—like the hip—that are difficult to aspirate or monitor. Other indications include pus in the synovial fluid, spread of infection to the soft tissues, or an inadequate clinical response to appropriate antibiotics after five to seven days. Otherwise, daily aspiration is the treatment of choice for an uncomplicated infected joint. Additionally, as is true in any acute monoarthritis, bed rest and optimal joint positioning are required to prevent the occurrence of joint deformation and harmful contractures. TH

Dr. Landis is a rheumatologist and a freelance writer.

Special thanks to Bradley Flansbaum, MD, for his assistance with this article.

References

- Tenenbaum J. Inflammatory musculoskeletal conditions in older adults. Geriatr Aging. 2005;8(3):14-17.

- Bieber JD, Terkeltaub RA. Gout: on the brink of novel therapeutic options for an ancient disease. Arthritis Rheum. 2004 Aug;50(8):2400-2414.

- Terkeltaub RA. Clinical practice. Gout. N Engl J Med. 2003 Oct 23;349(17):1647-1655.

- Leirisalo-Repo M. Early arthritis and infection. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2005 Jul;17(4):433-439.

- Siva C, Velazquez C, Mody A, et al. Diagnosing acute monoarthritis in adults: a practical approach for the family physician. Am Fam Physician. 2003 Jul 1;68(1):83-90.

Mrs. K, an 81-year-old golf-enthusiast admitted with congestive heart failure, now refuses to walk and complains of ankle pain. When you see her, she refuses to let even a bedsheet near her left ankle, and she claims that you did this to her.

Unfortunately, she’s probably right. Mrs. K also has a history of podagra, and she developed an acute gouty monoarthritis after receiving treatment with diuretics and aspirin. Gout—along with the other causes of inpatient acute monoarthritis (pseudogout, septic arthritis, and trauma)—are increasingly common diagnoses in the geriatric patient population. Because the elderly are uniquely predisposed to losing functional independence following an acute attack, making a timely diagnosis is particularly important in this age group. And though the patient’s clinical features may point toward an etiology, making the correct diagnosis ultimately depends on the results of the joint tap.

Gout

Gout occurs in patients with high serum levels of uric acid, though not all hyperuricemic patients develop gout. Among elderly hospitalized patients with hyperuricemia, approximately 65% have significant renal impairment, and others have advanced hypertension, coronary artery disease, and congestive heart failure. Over time, high serum uric acid levels may lead to the deposition of monosodium urate crystals in the joints; these lesions are the precursors of a gouty attack.

Gouty attacks occur when crystal deposits become inflamed. The inflammation may be triggered by a medication-induced change in uric acid concentration or by a medical condition, including acute illness, trauma, surgery, and dehydration. (See Table 1, p.18.) Though some elderly patients with acute gouty arthritis will manifest confusion or a sudden change in ambulatory status, most will present with a monoarthritis and a rise in temperature. Gout is suspected clinically when the first metatarsal phalangeal joint is involved (podagra), but other commonly involved joints include the ankle and the knee. Uric acid levels in the blood are usually elevated but can also temporarily normalize or even dip low during attacks. An X-ray of the involved joint may be normal or may already show the characteristic erosive lesion of gout, the “overhanging edge.”

Making the correct diagnosis is dependent upon visualizing intracellular, needle-shaped, negatively birefringent crystals in the synovial fluid. After the fluid is removed from the affected joint, it should be examined under polarized light within two hours; if more time is needed, the fluid can be refrigerated for up to 12 hours. Co-infection of a gouty joint has been described in the elderly population, and the synovial fluid should be sent to the laboratory for a cell count, Gram’s stain, and culture, as well as glucose and lactate levels. (See Table 2, below.)

Direct in-hospital treatment of gout toward alleviating the current attack, preventing future attacks, and providing appropriate antibiotic coverage in suspected co-infected cases until joint culture results are finalized. Treatment options for the acute attack include NSAIDs and corticosteroids—either oral or intra-articular. Hourly oral colchicine is not a good option for an elderly patient because the diarrhea that ensues is particularly disruptive. Nor is IV colchicine a good option thanks to its side-effect profile that renders it unusable in patients with reduced renal function. The treatment of hyperuricemia with allopurinol should not be undertaken during the acute attack because any change in the serum uric acid concentration will serve only to exacerbate the current inflammation.

Anti-inflammatory doses of NSAIDs are effective and will shorten the duration of symptoms substantially. Seven to 10 days of indomethacin at a dose of 50 mg taken orally three times daily is the traditional choice, and though it is generally conceded that ibuprofen and naproxen also work well, no comparative trials have been performed. Elderly patients are at increased risk for adverse effects from NSAIDs, particularly those patients with severely reduced renal function, gastropathy, asthma, congestive heart failure, or other intravascularly depleted states. Gastric mucosal protection, using proton-pump inhibitors, and careful monitoring of fluid status, renal function, and mental status are of particular concern in this population.

Because recent research indicates that COX-2 inhibitors have thrombotic potential and are contraindicated in patients at high risk for cardiovascular events or stroke, the extent to which they can be used in an elderly patient with an acute gouty attack is limited. A traditional NSAID in combination with a proton-pump inhibitor may be as effective as a COX-2 inhibitor in reducing the risk of gastroduodenal toxicity, however.

Corticosteroids—given either orally or intra-articularly—are an appropriate treatment for patients who can’t tolerate an NSAID. As long as a septic joint has been excluded, an intra-articular injection of 40–80 mg triamcinolone acetonide or 40 mg of methylprednisolone acetate will result in major improvement within 24 hours for most patients. Another option is a seven- to 10-day course of oral prednisone, starting with 40 mg on day one and reducing the dosage by 5 mg/day. Elderly patients taking oral prednisone should also receive adequate calcium, vitamin D, and a proton pump inhibitor for gastrointestinal protection, as well as close monitoring of blood pressure, glucose, and mental status.

If a patient has a history of frequent attacks or tophi, has a serum uric acid level higher than 12 mg/dl, or is consistently receiving high doses of diuretics, that person is at high risk for subsequent attacks and should receive prophylactic treatment with either a low-dose daily NSAID or a renally dosed oral colchicine.

Pseudogout

Pseudogout is the articular manifestation of calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate (CPPD) deposition, and this process is associated with aging as well as with various endocrinopathies, the most common of which is hyperparathyroidism. (See Table 3, below.) The shedding of CPPD crystals initiates an inflammatory process, and these crystals invoke an inflammatory response in much the same manner as uric acid crystals.

While the precipitants of a pseudogout attack are less well defined than those of gout, dehydration and joint surgery have both been identified as predisposing factors. The acute monoarticular pain and swelling (the knee is most common, followed by the ankle and then any other synovial joint) that ensues usually has a more insidious onset, and an X-ray may show chondrocalcinosis within the joint space. The diagnosis is confirmed by the demonstration of intracellular CPPD crystals in the aspirated joint fluid. Though less easily seen than monosodium urate crystals, rhomboidal crystals that display weakly positive birefringence under polarized light will be revealed with careful observation. Vitally important to the diagnosis of any crystal-associated arthritis is the exclusion of septic arthritis. To this end, conduct synovial fluid and blood cultures even if the suspicion of sepsis is low.

Treatment goals for pseudogout center on the abatement of the current arthritis and the exclusion of an infected joint or a concurrent metabolic syndrome. NSAIDs are the mainstay of therapy for the management of pseudogout; they are prescribed in anti-inflammatory doses similar to those used in the treatment of gout. Corticosteroids can also be used, particularly an intra-articular injection, as long as infection has been excluded. As with any crystal arthropathy, a septic joint should be considered and treated in high-risk patients even before the results of the joint fluid cultures are available. (See Table 4, above.)

Septic Arthritis

Even with timely antibacterial treatment, an elderly patient with a septic joint has a 7% to 32% mortality rate. Staphylococcus and Streptococcus are the most commonly cultured pathogens, but consider E. coli, Pseudomonas, and Klebsiella species in patients with diabetes mellitus, malignancy, or other debilitating chronic syndromes; less common agents include tuberculosis and gonococcus. Fever may be present, but a recent study revealed that fewer than 60% of geriatric patients with septic arthritis presented with a febrile illness. Thus, systemic features are not reliable enough to warrant making or excluding the diagnosis of septic arthritis without examination of the synovial fluid. (See Table 5, below.)

Send synovial fluid for leukocyte count, Gram’s stain, and culture in all suspected cases, and several studies suggest that the diagnostic yield may be improved with direct inoculation of fluid into blood culture vials or isolator tubes. Synovial fluid will also show very low glucose (less than 25% of simultaneous plasma glucose) and very high lactate (greater than 10 mm/l) in the untreated bacterial septic joint.

Treatment of a septic joint includes both appropriate antimicrobial therapy and joint drainage. Three weeks of parenteral antimicrobial therapy directed against the isolated pathogen is usually sufficient once the affected joint has been drained. Surgical drainage is indicated in joints—like the hip—that are difficult to aspirate or monitor. Other indications include pus in the synovial fluid, spread of infection to the soft tissues, or an inadequate clinical response to appropriate antibiotics after five to seven days. Otherwise, daily aspiration is the treatment of choice for an uncomplicated infected joint. Additionally, as is true in any acute monoarthritis, bed rest and optimal joint positioning are required to prevent the occurrence of joint deformation and harmful contractures. TH

Dr. Landis is a rheumatologist and a freelance writer.

Special thanks to Bradley Flansbaum, MD, for his assistance with this article.

References

- Tenenbaum J. Inflammatory musculoskeletal conditions in older adults. Geriatr Aging. 2005;8(3):14-17.

- Bieber JD, Terkeltaub RA. Gout: on the brink of novel therapeutic options for an ancient disease. Arthritis Rheum. 2004 Aug;50(8):2400-2414.

- Terkeltaub RA. Clinical practice. Gout. N Engl J Med. 2003 Oct 23;349(17):1647-1655.

- Leirisalo-Repo M. Early arthritis and infection. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2005 Jul;17(4):433-439.

- Siva C, Velazquez C, Mody A, et al. Diagnosing acute monoarthritis in adults: a practical approach for the family physician. Am Fam Physician. 2003 Jul 1;68(1):83-90.