User login

Intermittent fasting is the purposeful, restricted intake of food (and sometimes water), usually for health or religious reasons. Common forms are alternative-day fasting or time-restricted fasting, with variable ratios of days or hours for fasting and eating/drinking.1 For example, fasting during Ramadan, the ninth month of the Islamic calendar, occurs from dawn to sunset, for a variable duration due to latitude and seasonal shifts.2 Clinicians are likely to care for a patient who occasionally fasts. While there are potential benefits of fasting, clinicians need to consider the implications for patients who fast, particularly those receiving psychotropic medications.

Potential benefits for weight loss, mood

Some research suggests fasting is popular and may have benefits for an individual’s physical and mental health. In a 2020 online poll (N = 1,241), 24% of respondents said they had tried intermittent fasting, and 87% said the practice was very effective (50%) or somewhat effective (37%) in helping them lose weight.3 While more randomized control trials are needed to examine the practice’s effectiveness in promoting and maintaining weight loss, fasting has been linked to better glucose control in both humans and animals, and patients may have better adherence with fasting compared to caloric restriction alone.1 Improved mood, alertness, tranquility, and sometimes euphoria have been documented among individuals who fast, but these benefits may not be sustained.4 A prospective study of 462 participants who fasted during Ramadan found the practice reduced depression in patients with diabetes, possibly due to mindfulness, decreased inflammation from improved insulin sensitivity, and/or social cohesion.5

Be aware of the potential risks

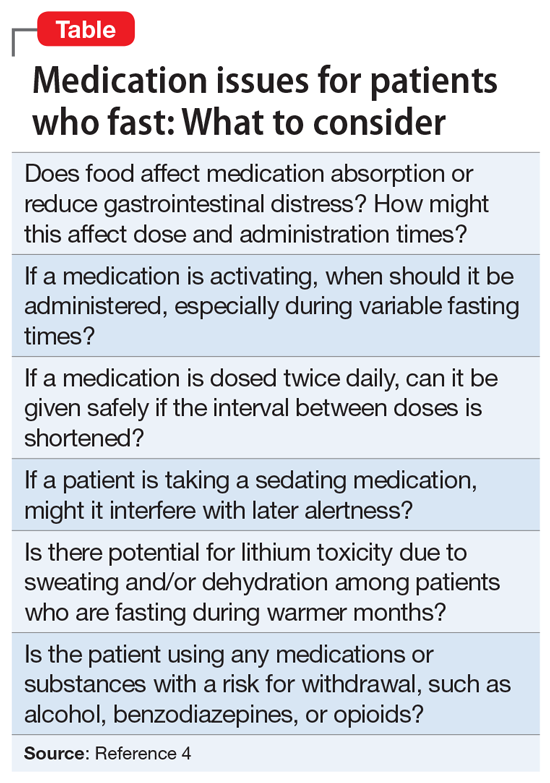

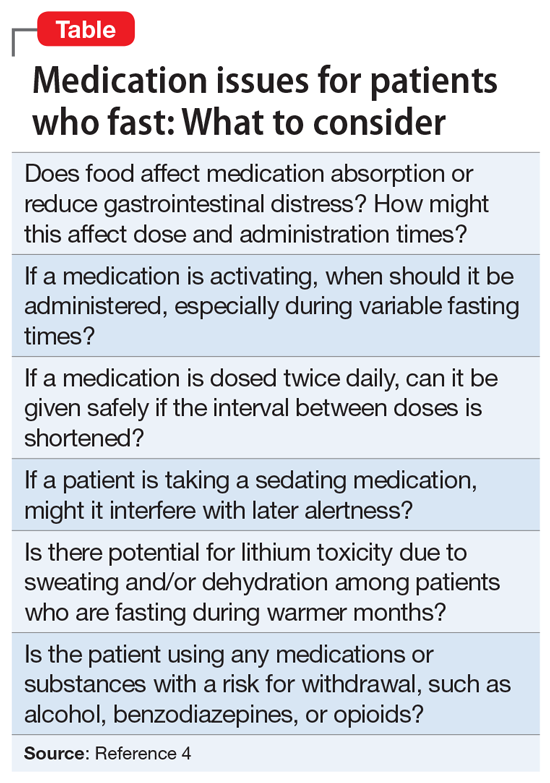

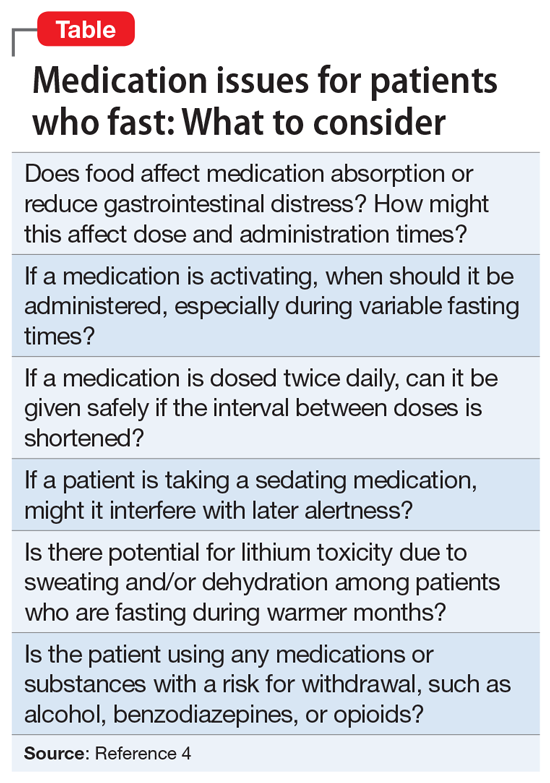

Fasting may either improve or destabilize mood in people with bipolar disorder by disrupting circadian rhythm and sleep.2 Fasting might exacerbate underlying eating disorders.2 Increased dehydration escalates the risk for orthostatic hypotension, which might require discontinuing clozapine.6 Hypotension and toxicity might arise during lithium pharmacotherapy. The Table4 summarizes things to consider when caring for a patient who fasts while receiving pharmacotherapy.

Provide patients with guidance

Advise patients not to fast if you believe it might exacerbate their mental illness, and encourage them to discuss with their primary care physicians any potential worsening of physical illnesses.2 When caring for a patient who fasts for religious reasons, consider consulting with the patient’s religious leaders.2 If patients choose to fast, monitor them for mood destabilization and/or medication adverse effects. If possible, avoid altering drug treatment regimens during fasting, and carefully monitor whenever a pharmaceutical change is necessary. When appropriate, the use of long-acting injectable medications may minimize adverse effects while maintaining mood stability. Encourage patients who fast to ensure they remain hydrated and practice sleep hygiene while they fast.7

1. Dong TA, Sandesara PB, Dhindsa DS, et al. Intermittent fasting: a heart healthy dietary pattern? Am J Med. 2020;133(8):901-907.

2. Fond G, Macgregor A, Leboyer M, et al. Fasting in mood disorders: neurobiology and effectiveness. A review of the literature. Psychiatry Res. 2013;209(3):253-258.

3. Ballard J. Americans say this popular diet is effective and inexpensive. YouGov. February 24, 2020. Accessed January 6, 2022. https://today.yougov.com/topics/food/articles-reports/2020/02/24/most-effective-diet-intermittent-fasting-poll

4. Furqan Z, Awaad R, Kurdyak P, et al. Considerations for clinicians treating Muslim patients with psychiatric disorders during Ramadan. Lancet Psychiatry. 2019;6(7):556-557.

5. Al-Ozairi E, AlAwadhi MM, Al-Ozairi A, et al. A prospective study of the effect of fasting during the month of Ramadan on depression and diabetes distress in people with type 2 diabetes. Diabet Res Clin Pract. 2019;153:145-149.

6. Chehovich C, Demler TL, Leppien E. Impact of Ramadan fasting on medical and psychiatric health. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2019;34(6):317-322.

7. Farooq S, Nazar Z, Akhtar J, et al. Effect of fasting during Ramadan on serum lithium level and mental state in bipolar affective disorder. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2010;25(6):323-327.

Intermittent fasting is the purposeful, restricted intake of food (and sometimes water), usually for health or religious reasons. Common forms are alternative-day fasting or time-restricted fasting, with variable ratios of days or hours for fasting and eating/drinking.1 For example, fasting during Ramadan, the ninth month of the Islamic calendar, occurs from dawn to sunset, for a variable duration due to latitude and seasonal shifts.2 Clinicians are likely to care for a patient who occasionally fasts. While there are potential benefits of fasting, clinicians need to consider the implications for patients who fast, particularly those receiving psychotropic medications.

Potential benefits for weight loss, mood

Some research suggests fasting is popular and may have benefits for an individual’s physical and mental health. In a 2020 online poll (N = 1,241), 24% of respondents said they had tried intermittent fasting, and 87% said the practice was very effective (50%) or somewhat effective (37%) in helping them lose weight.3 While more randomized control trials are needed to examine the practice’s effectiveness in promoting and maintaining weight loss, fasting has been linked to better glucose control in both humans and animals, and patients may have better adherence with fasting compared to caloric restriction alone.1 Improved mood, alertness, tranquility, and sometimes euphoria have been documented among individuals who fast, but these benefits may not be sustained.4 A prospective study of 462 participants who fasted during Ramadan found the practice reduced depression in patients with diabetes, possibly due to mindfulness, decreased inflammation from improved insulin sensitivity, and/or social cohesion.5

Be aware of the potential risks

Fasting may either improve or destabilize mood in people with bipolar disorder by disrupting circadian rhythm and sleep.2 Fasting might exacerbate underlying eating disorders.2 Increased dehydration escalates the risk for orthostatic hypotension, which might require discontinuing clozapine.6 Hypotension and toxicity might arise during lithium pharmacotherapy. The Table4 summarizes things to consider when caring for a patient who fasts while receiving pharmacotherapy.

Provide patients with guidance

Advise patients not to fast if you believe it might exacerbate their mental illness, and encourage them to discuss with their primary care physicians any potential worsening of physical illnesses.2 When caring for a patient who fasts for religious reasons, consider consulting with the patient’s religious leaders.2 If patients choose to fast, monitor them for mood destabilization and/or medication adverse effects. If possible, avoid altering drug treatment regimens during fasting, and carefully monitor whenever a pharmaceutical change is necessary. When appropriate, the use of long-acting injectable medications may minimize adverse effects while maintaining mood stability. Encourage patients who fast to ensure they remain hydrated and practice sleep hygiene while they fast.7

Intermittent fasting is the purposeful, restricted intake of food (and sometimes water), usually for health or religious reasons. Common forms are alternative-day fasting or time-restricted fasting, with variable ratios of days or hours for fasting and eating/drinking.1 For example, fasting during Ramadan, the ninth month of the Islamic calendar, occurs from dawn to sunset, for a variable duration due to latitude and seasonal shifts.2 Clinicians are likely to care for a patient who occasionally fasts. While there are potential benefits of fasting, clinicians need to consider the implications for patients who fast, particularly those receiving psychotropic medications.

Potential benefits for weight loss, mood

Some research suggests fasting is popular and may have benefits for an individual’s physical and mental health. In a 2020 online poll (N = 1,241), 24% of respondents said they had tried intermittent fasting, and 87% said the practice was very effective (50%) or somewhat effective (37%) in helping them lose weight.3 While more randomized control trials are needed to examine the practice’s effectiveness in promoting and maintaining weight loss, fasting has been linked to better glucose control in both humans and animals, and patients may have better adherence with fasting compared to caloric restriction alone.1 Improved mood, alertness, tranquility, and sometimes euphoria have been documented among individuals who fast, but these benefits may not be sustained.4 A prospective study of 462 participants who fasted during Ramadan found the practice reduced depression in patients with diabetes, possibly due to mindfulness, decreased inflammation from improved insulin sensitivity, and/or social cohesion.5

Be aware of the potential risks

Fasting may either improve or destabilize mood in people with bipolar disorder by disrupting circadian rhythm and sleep.2 Fasting might exacerbate underlying eating disorders.2 Increased dehydration escalates the risk for orthostatic hypotension, which might require discontinuing clozapine.6 Hypotension and toxicity might arise during lithium pharmacotherapy. The Table4 summarizes things to consider when caring for a patient who fasts while receiving pharmacotherapy.

Provide patients with guidance

Advise patients not to fast if you believe it might exacerbate their mental illness, and encourage them to discuss with their primary care physicians any potential worsening of physical illnesses.2 When caring for a patient who fasts for religious reasons, consider consulting with the patient’s religious leaders.2 If patients choose to fast, monitor them for mood destabilization and/or medication adverse effects. If possible, avoid altering drug treatment regimens during fasting, and carefully monitor whenever a pharmaceutical change is necessary. When appropriate, the use of long-acting injectable medications may minimize adverse effects while maintaining mood stability. Encourage patients who fast to ensure they remain hydrated and practice sleep hygiene while they fast.7

1. Dong TA, Sandesara PB, Dhindsa DS, et al. Intermittent fasting: a heart healthy dietary pattern? Am J Med. 2020;133(8):901-907.

2. Fond G, Macgregor A, Leboyer M, et al. Fasting in mood disorders: neurobiology and effectiveness. A review of the literature. Psychiatry Res. 2013;209(3):253-258.

3. Ballard J. Americans say this popular diet is effective and inexpensive. YouGov. February 24, 2020. Accessed January 6, 2022. https://today.yougov.com/topics/food/articles-reports/2020/02/24/most-effective-diet-intermittent-fasting-poll

4. Furqan Z, Awaad R, Kurdyak P, et al. Considerations for clinicians treating Muslim patients with psychiatric disorders during Ramadan. Lancet Psychiatry. 2019;6(7):556-557.

5. Al-Ozairi E, AlAwadhi MM, Al-Ozairi A, et al. A prospective study of the effect of fasting during the month of Ramadan on depression and diabetes distress in people with type 2 diabetes. Diabet Res Clin Pract. 2019;153:145-149.

6. Chehovich C, Demler TL, Leppien E. Impact of Ramadan fasting on medical and psychiatric health. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2019;34(6):317-322.

7. Farooq S, Nazar Z, Akhtar J, et al. Effect of fasting during Ramadan on serum lithium level and mental state in bipolar affective disorder. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2010;25(6):323-327.

1. Dong TA, Sandesara PB, Dhindsa DS, et al. Intermittent fasting: a heart healthy dietary pattern? Am J Med. 2020;133(8):901-907.

2. Fond G, Macgregor A, Leboyer M, et al. Fasting in mood disorders: neurobiology and effectiveness. A review of the literature. Psychiatry Res. 2013;209(3):253-258.

3. Ballard J. Americans say this popular diet is effective and inexpensive. YouGov. February 24, 2020. Accessed January 6, 2022. https://today.yougov.com/topics/food/articles-reports/2020/02/24/most-effective-diet-intermittent-fasting-poll

4. Furqan Z, Awaad R, Kurdyak P, et al. Considerations for clinicians treating Muslim patients with psychiatric disorders during Ramadan. Lancet Psychiatry. 2019;6(7):556-557.

5. Al-Ozairi E, AlAwadhi MM, Al-Ozairi A, et al. A prospective study of the effect of fasting during the month of Ramadan on depression and diabetes distress in people with type 2 diabetes. Diabet Res Clin Pract. 2019;153:145-149.

6. Chehovich C, Demler TL, Leppien E. Impact of Ramadan fasting on medical and psychiatric health. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2019;34(6):317-322.

7. Farooq S, Nazar Z, Akhtar J, et al. Effect of fasting during Ramadan on serum lithium level and mental state in bipolar affective disorder. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2010;25(6):323-327.