User login

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

I want to help people suffering from long COVID as much as anyone. But we have a real problem. In brief, we are being too inclusive. The first thing you learn, when you start studying the epidemiology of diseases, is that you need a good case definition. And our case definition for long COVID sucks. Just last week, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM) issued a definition of long COVID with the aim of “improving consistency, documentation, and treatment.” Good news, right? Here’s the definition: “Long COVID is an infection-associated chronic condition that occurs after SARS-CoV-2 infection and is present for at least 3 months as a continuous, relapsing and remitting, or progressive disease state that affects one or more organ systems.”

This is not helpful. The symptoms can be in any organ system, can be continuous or relapsing and remitting. Basically, if you’ve had COVID — and essentially all of us have by now — and you have any symptom, even one that comes and goes, 3 months after that, it’s long COVID. They don’t even specify that it has to be a new symptom.

And I have sort of a case study in this problem today, based on a paper getting a lot of press suggesting that one out of every five people has long COVID.

We are talking about this study, “Epidemiologic Features of Recovery From SARS-CoV-2 Infection,” appearing in JAMA Network Open this week. While I think the idea is important, the study really highlights why it can be so hard to study long COVID.

As part of efforts to understand long COVID, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) leveraged 14 of its ongoing cohort studies. The NIH has multiple longitudinal cohort studies that follow various groups of people over time. You may have heard of the REGARDS study, for example, which focuses on cardiovascular risks to people living in the southern United States. Or the ARIC study, which followed adults in four communities across the United States for the development of heart disease. All 14 of the cohorts in this study are long-running projects with ongoing data collection. So, it was not a huge lift to add some questions to the yearly surveys and studies the participants were already getting.

To wit: “Do you think that you have had COVID-19?” and “Would you say that you are completely recovered now?” Those who said they weren’t fully recovered were asked how long it had been since their infection, and anyone who answered with a duration > 90 days was considered to have long COVID.

So, we have self-report of infection, self-report of duration of symptoms, and self-report of recovery. This is fine, of course; individuals’ perceptions of their own health are meaningful. But the vagaries inherent in those perceptions are going to muddy the waters as we attempt to discover the true nature of the long COVID syndrome.

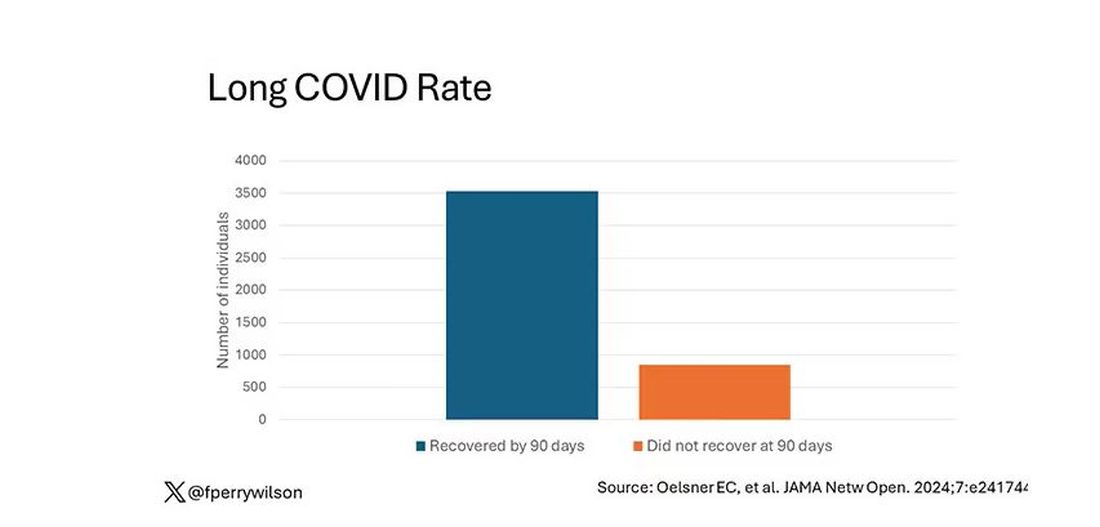

But let’s look at some results. Out of 4708 individuals studied, 842 (17.9%) had not recovered by 90 days.

This study included not only people hospitalized with COVID, as some prior long COVID studies did, but people self-diagnosed, tested at home, etc. This estimate is as reflective of the broader US population as we can get.

And there are some interesting trends here.

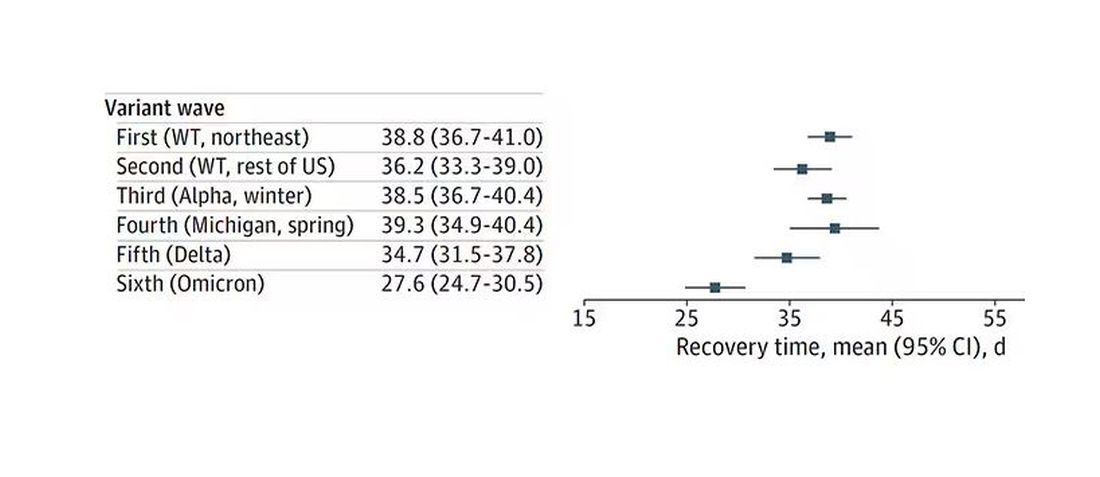

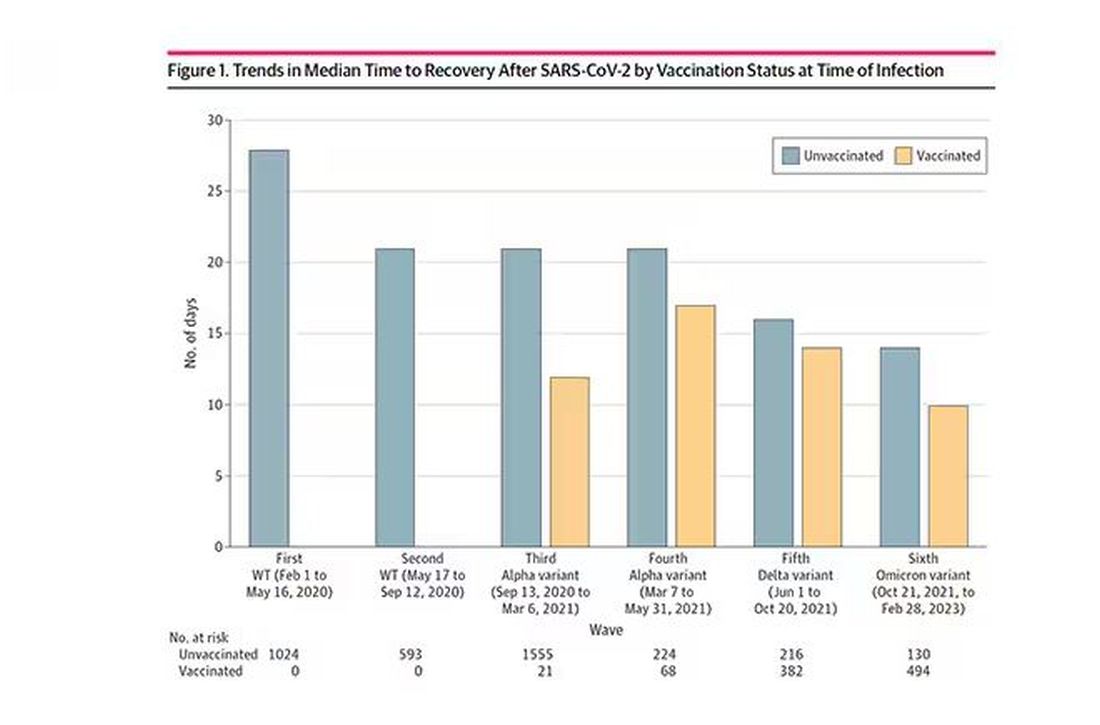

Recovery time was longer in the first waves of COVID than in the Omicron wave.

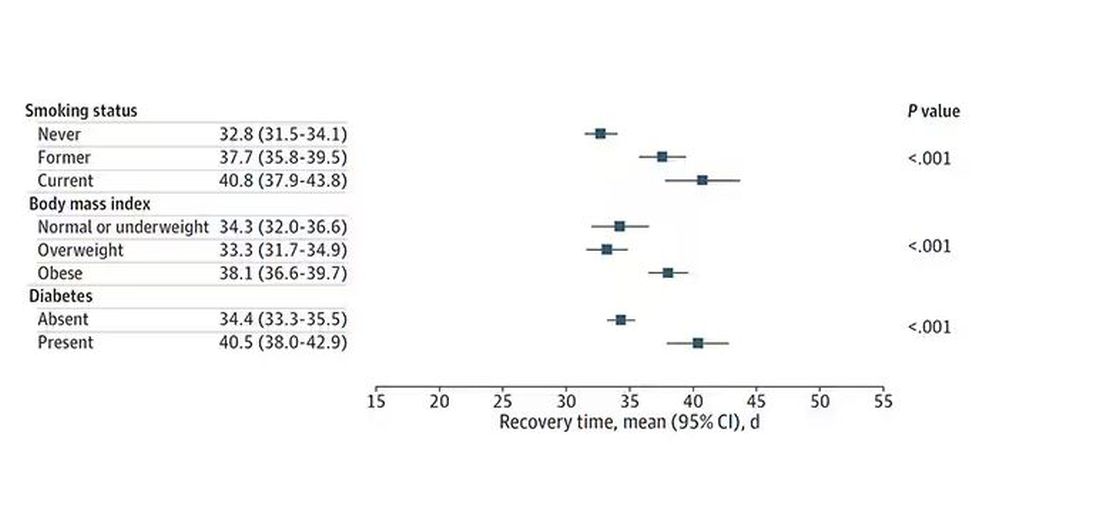

Recovery times were longer for smokers, those with diabetes, and those who were obese.

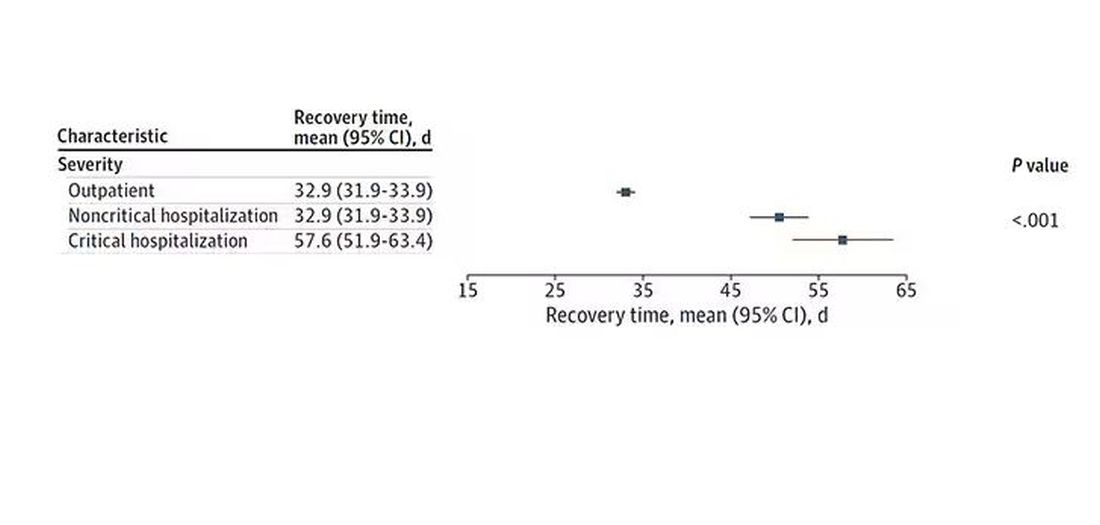

Recovery times were longer if the disease was more severe, in general. Though there is an unusual finding that women had longer recovery times despite their lower average severity of illness.

Vaccination was associated with shorter recovery times, as you can see here.

This is all quite interesting. It’s clear that people feel they are sick for a while after COVID. But we need to understand whether these symptoms are due to the lingering effects of a bad infection that knocks you down a peg, or to an ongoing syndrome — this thing we call long COVID — that has a physiologic basis and thus can be treated. And this study doesn’t help us much with that.

Not that this was the authors’ intention. This is a straight-up epidemiology study. But the problem is deeper than that. Let’s imagine that you want to really dig into this long COVID thing and get blood samples from people with it, ideally from controls with some other respiratory virus infection, and do all kinds of genetic and proteomic studies and stuff to really figure out what’s going on. Who do you enroll to be in the long COVID group? Do you enroll anyone who says they had COVID and still has some symptom more than 90 days after? You are going to find an awful lot of eligible people, and I guarantee that if there is a pathognomonic signature of long COVID, not all of them will have it.

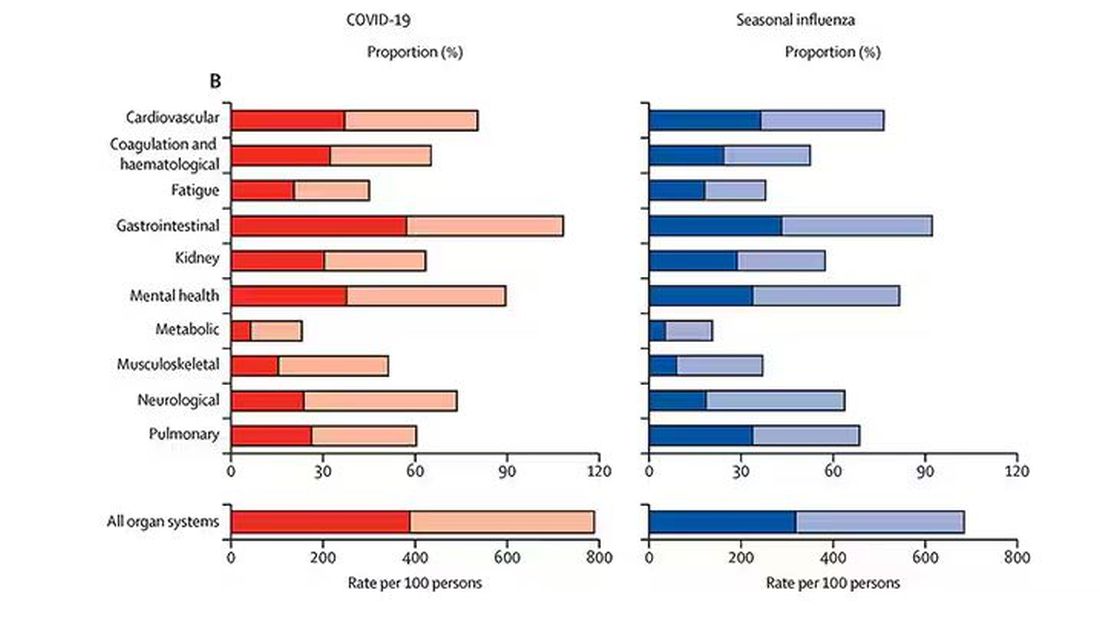

And what about other respiratory viruses? This study in The Lancet Infectious Diseases compared long-term outcomes among hospitalized patients with COVID vs influenza. In general, the COVID outcomes are worse, but let’s not knock the concept of “long flu.” Across the board, roughly 50% of people report symptoms across any given organ system.

What this is all about is something called misclassification bias, a form of information bias that arises in a study where you label someone as diseased when they are not, or vice versa. If this happens at random, it’s bad; you’ve lost your ability to distinguish characteristics from the diseased and nondiseased population.

When it’s not random, it’s really bad. If we are more likely to misclassify women as having long COVID, for example, then it will appear that long COVID is more likely among women, or more likely among those with higher estrogen levels, or something. And that might simply be wrong.

I’m not saying that’s what happened here; this study does a really great job of what it set out to do, which was to describe the patterns of lingering symptoms after COVID. But we are not going to make progress toward understanding long COVID until we are less inclusive with our case definition. To paraphrase Syndrome from The Incredibles: If everyone has long COVID, then no one does.

Dr. Wilson is associate professor of medicine and public health and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

I want to help people suffering from long COVID as much as anyone. But we have a real problem. In brief, we are being too inclusive. The first thing you learn, when you start studying the epidemiology of diseases, is that you need a good case definition. And our case definition for long COVID sucks. Just last week, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM) issued a definition of long COVID with the aim of “improving consistency, documentation, and treatment.” Good news, right? Here’s the definition: “Long COVID is an infection-associated chronic condition that occurs after SARS-CoV-2 infection and is present for at least 3 months as a continuous, relapsing and remitting, or progressive disease state that affects one or more organ systems.”

This is not helpful. The symptoms can be in any organ system, can be continuous or relapsing and remitting. Basically, if you’ve had COVID — and essentially all of us have by now — and you have any symptom, even one that comes and goes, 3 months after that, it’s long COVID. They don’t even specify that it has to be a new symptom.

And I have sort of a case study in this problem today, based on a paper getting a lot of press suggesting that one out of every five people has long COVID.

We are talking about this study, “Epidemiologic Features of Recovery From SARS-CoV-2 Infection,” appearing in JAMA Network Open this week. While I think the idea is important, the study really highlights why it can be so hard to study long COVID.

As part of efforts to understand long COVID, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) leveraged 14 of its ongoing cohort studies. The NIH has multiple longitudinal cohort studies that follow various groups of people over time. You may have heard of the REGARDS study, for example, which focuses on cardiovascular risks to people living in the southern United States. Or the ARIC study, which followed adults in four communities across the United States for the development of heart disease. All 14 of the cohorts in this study are long-running projects with ongoing data collection. So, it was not a huge lift to add some questions to the yearly surveys and studies the participants were already getting.

To wit: “Do you think that you have had COVID-19?” and “Would you say that you are completely recovered now?” Those who said they weren’t fully recovered were asked how long it had been since their infection, and anyone who answered with a duration > 90 days was considered to have long COVID.

So, we have self-report of infection, self-report of duration of symptoms, and self-report of recovery. This is fine, of course; individuals’ perceptions of their own health are meaningful. But the vagaries inherent in those perceptions are going to muddy the waters as we attempt to discover the true nature of the long COVID syndrome.

But let’s look at some results. Out of 4708 individuals studied, 842 (17.9%) had not recovered by 90 days.

This study included not only people hospitalized with COVID, as some prior long COVID studies did, but people self-diagnosed, tested at home, etc. This estimate is as reflective of the broader US population as we can get.

And there are some interesting trends here.

Recovery time was longer in the first waves of COVID than in the Omicron wave.

Recovery times were longer for smokers, those with diabetes, and those who were obese.

Recovery times were longer if the disease was more severe, in general. Though there is an unusual finding that women had longer recovery times despite their lower average severity of illness.

Vaccination was associated with shorter recovery times, as you can see here.

This is all quite interesting. It’s clear that people feel they are sick for a while after COVID. But we need to understand whether these symptoms are due to the lingering effects of a bad infection that knocks you down a peg, or to an ongoing syndrome — this thing we call long COVID — that has a physiologic basis and thus can be treated. And this study doesn’t help us much with that.

Not that this was the authors’ intention. This is a straight-up epidemiology study. But the problem is deeper than that. Let’s imagine that you want to really dig into this long COVID thing and get blood samples from people with it, ideally from controls with some other respiratory virus infection, and do all kinds of genetic and proteomic studies and stuff to really figure out what’s going on. Who do you enroll to be in the long COVID group? Do you enroll anyone who says they had COVID and still has some symptom more than 90 days after? You are going to find an awful lot of eligible people, and I guarantee that if there is a pathognomonic signature of long COVID, not all of them will have it.

And what about other respiratory viruses? This study in The Lancet Infectious Diseases compared long-term outcomes among hospitalized patients with COVID vs influenza. In general, the COVID outcomes are worse, but let’s not knock the concept of “long flu.” Across the board, roughly 50% of people report symptoms across any given organ system.

What this is all about is something called misclassification bias, a form of information bias that arises in a study where you label someone as diseased when they are not, or vice versa. If this happens at random, it’s bad; you’ve lost your ability to distinguish characteristics from the diseased and nondiseased population.

When it’s not random, it’s really bad. If we are more likely to misclassify women as having long COVID, for example, then it will appear that long COVID is more likely among women, or more likely among those with higher estrogen levels, or something. And that might simply be wrong.

I’m not saying that’s what happened here; this study does a really great job of what it set out to do, which was to describe the patterns of lingering symptoms after COVID. But we are not going to make progress toward understanding long COVID until we are less inclusive with our case definition. To paraphrase Syndrome from The Incredibles: If everyone has long COVID, then no one does.

Dr. Wilson is associate professor of medicine and public health and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

I want to help people suffering from long COVID as much as anyone. But we have a real problem. In brief, we are being too inclusive. The first thing you learn, when you start studying the epidemiology of diseases, is that you need a good case definition. And our case definition for long COVID sucks. Just last week, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM) issued a definition of long COVID with the aim of “improving consistency, documentation, and treatment.” Good news, right? Here’s the definition: “Long COVID is an infection-associated chronic condition that occurs after SARS-CoV-2 infection and is present for at least 3 months as a continuous, relapsing and remitting, or progressive disease state that affects one or more organ systems.”

This is not helpful. The symptoms can be in any organ system, can be continuous or relapsing and remitting. Basically, if you’ve had COVID — and essentially all of us have by now — and you have any symptom, even one that comes and goes, 3 months after that, it’s long COVID. They don’t even specify that it has to be a new symptom.

And I have sort of a case study in this problem today, based on a paper getting a lot of press suggesting that one out of every five people has long COVID.

We are talking about this study, “Epidemiologic Features of Recovery From SARS-CoV-2 Infection,” appearing in JAMA Network Open this week. While I think the idea is important, the study really highlights why it can be so hard to study long COVID.

As part of efforts to understand long COVID, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) leveraged 14 of its ongoing cohort studies. The NIH has multiple longitudinal cohort studies that follow various groups of people over time. You may have heard of the REGARDS study, for example, which focuses on cardiovascular risks to people living in the southern United States. Or the ARIC study, which followed adults in four communities across the United States for the development of heart disease. All 14 of the cohorts in this study are long-running projects with ongoing data collection. So, it was not a huge lift to add some questions to the yearly surveys and studies the participants were already getting.

To wit: “Do you think that you have had COVID-19?” and “Would you say that you are completely recovered now?” Those who said they weren’t fully recovered were asked how long it had been since their infection, and anyone who answered with a duration > 90 days was considered to have long COVID.

So, we have self-report of infection, self-report of duration of symptoms, and self-report of recovery. This is fine, of course; individuals’ perceptions of their own health are meaningful. But the vagaries inherent in those perceptions are going to muddy the waters as we attempt to discover the true nature of the long COVID syndrome.

But let’s look at some results. Out of 4708 individuals studied, 842 (17.9%) had not recovered by 90 days.

This study included not only people hospitalized with COVID, as some prior long COVID studies did, but people self-diagnosed, tested at home, etc. This estimate is as reflective of the broader US population as we can get.

And there are some interesting trends here.

Recovery time was longer in the first waves of COVID than in the Omicron wave.

Recovery times were longer for smokers, those with diabetes, and those who were obese.

Recovery times were longer if the disease was more severe, in general. Though there is an unusual finding that women had longer recovery times despite their lower average severity of illness.

Vaccination was associated with shorter recovery times, as you can see here.

This is all quite interesting. It’s clear that people feel they are sick for a while after COVID. But we need to understand whether these symptoms are due to the lingering effects of a bad infection that knocks you down a peg, or to an ongoing syndrome — this thing we call long COVID — that has a physiologic basis and thus can be treated. And this study doesn’t help us much with that.

Not that this was the authors’ intention. This is a straight-up epidemiology study. But the problem is deeper than that. Let’s imagine that you want to really dig into this long COVID thing and get blood samples from people with it, ideally from controls with some other respiratory virus infection, and do all kinds of genetic and proteomic studies and stuff to really figure out what’s going on. Who do you enroll to be in the long COVID group? Do you enroll anyone who says they had COVID and still has some symptom more than 90 days after? You are going to find an awful lot of eligible people, and I guarantee that if there is a pathognomonic signature of long COVID, not all of them will have it.

And what about other respiratory viruses? This study in The Lancet Infectious Diseases compared long-term outcomes among hospitalized patients with COVID vs influenza. In general, the COVID outcomes are worse, but let’s not knock the concept of “long flu.” Across the board, roughly 50% of people report symptoms across any given organ system.

What this is all about is something called misclassification bias, a form of information bias that arises in a study where you label someone as diseased when they are not, or vice versa. If this happens at random, it’s bad; you’ve lost your ability to distinguish characteristics from the diseased and nondiseased population.

When it’s not random, it’s really bad. If we are more likely to misclassify women as having long COVID, for example, then it will appear that long COVID is more likely among women, or more likely among those with higher estrogen levels, or something. And that might simply be wrong.

I’m not saying that’s what happened here; this study does a really great job of what it set out to do, which was to describe the patterns of lingering symptoms after COVID. But we are not going to make progress toward understanding long COVID until we are less inclusive with our case definition. To paraphrase Syndrome from The Incredibles: If everyone has long COVID, then no one does.

Dr. Wilson is associate professor of medicine and public health and director of the Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator at Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.