User login

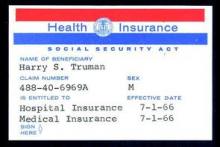

When President Lyndon B. Johnson signed Medicare into law on July 30, 1965, he vowed that the program would give seniors access to the “healing miracle of modern medicine” and save them from exhausting their savings when they became ill.

For the most part, the program has delivered on those bold promises. Americans over age 65 years are living longer, healthier lives, and they are doing so without fear that a trip to the hospital will lead to bankruptcy. That security has only increased over time, as Congress added prescription drug coverage and most recently, free preventive care. In 1972, the Medicare program was extended to the long-term disabled and those with end stage renal disease.

Medicare “fundamentally changed the way we thought about health in our nation for our seniors,” said Dr. Georges C. Benjamin, executive director of the American Public Health Association. “This probably was the most important tool to lift seniors out of poverty. The economic benefit of this, in addition to the health benefit, was enormous.”

Along with coverage of hospital stays and physician services for seniors under Medicare, the Social Security Act Amendments of 1965 also created Medicaid, a voluntary federal-state partnership to provide medical care and long-term care services to low-income Americans.

Changing medical practice

When combined with the Civil Rights Act of 1964, Medicare desegregated all hospitals that participated in the program. Prior to the start of Medicare on July 1, 1966, a large number of hospitals around the country were still racially segregated in some manner. In many areas of the South, a separate hospital system served the black community and were the only places where black physicians could train and practice (Milbank Q. 2005; 83: 247-69). But in a matter of months, hospitals across the country integrated their facilities and staff in a relative peaceful manner, according to a study conducted by the Commonwealth Fund.

“Now, physicians of color could not be kept out of hospitals as a matter of policy,” Dr. Benjamin said. “It dramatically improved practice opportunities for physicians and access to care opportunities for patients.”

Stuart Guterman, Ph.D., vice president for Medicare and cost control at the Commonwealth Fund, said it’s one of the lesser-known elements of Medicare’s history that the law became an impetus to overcoming racial barriers for both patients and physicians.

Changing payment incentives

Medicare payments opened up a significant new stream of revenue for hospitals that made desegregation more palatable. But hospitals weren’t the only ones who benefited financially from the new program.

Despite the American Medical Association’s fight against the creation of Medicare, during which officials famously decried the program as “socialized medicine,” physicians were financial winners under the new law, at least at first.

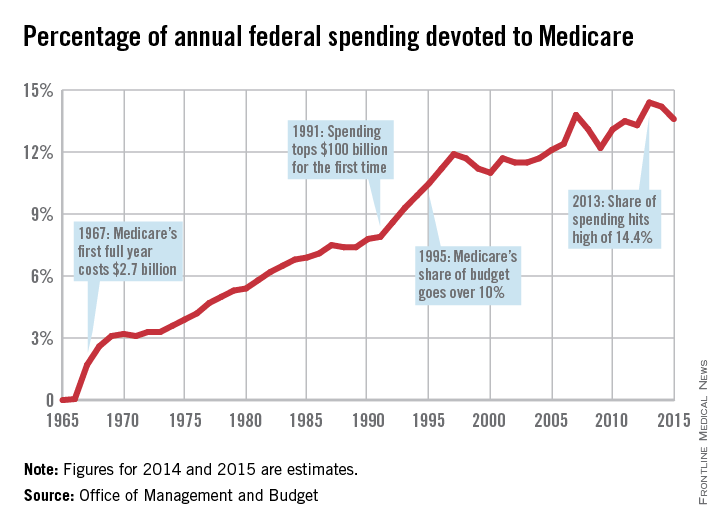

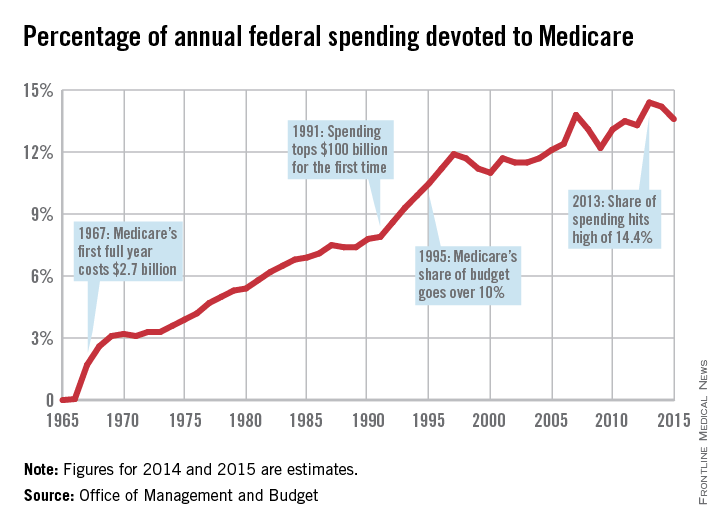

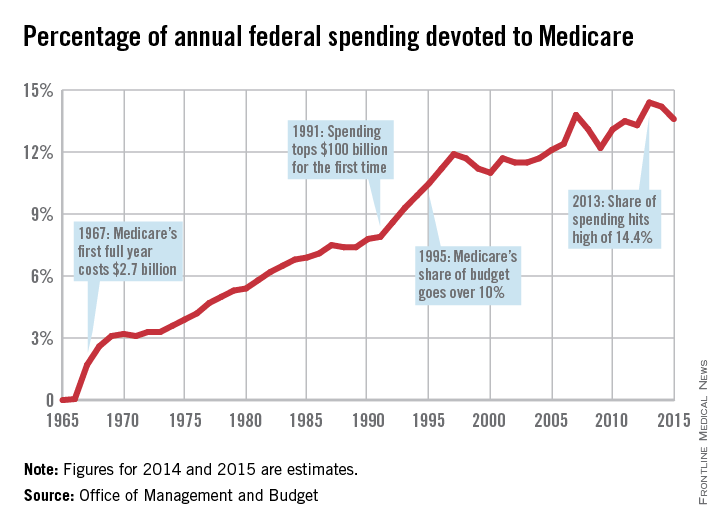

Much like hospitals, doctors got paid for the first time for treating patients who they had previously seen as charity care. And, in those early years of the Medicare program, the government paid on a charge basis. The result was that Medicare spending was quickly out of control.

Cost controls were added first for hospital care. In 1983, Medicare adopted the inpatient hospital prospective payment system, which replaced hospitals’ cost-based payments with the diagnosis-related group (DRG) system.

“Changing the notion of what hospitals did from each individual service or each individual day to the hospital stay, really changed the way hospital care was looked at,” Dr. Guterman said.

It took somewhat longer for federal health officials to tackle payment on the physician side. Throughout the 1980s, Congress froze physician payment rates in an effort to address rising costs. In 1984, Congress established the Participating Physicians’ Program, which required physicians to accept assignment for all Medicare patients and services rather than on a service-by-service basis. It also barred balance billing of Medicare beneficiaries.

In 1989, Congress made the most significant change yet to physician payment, creating the Resource-Based Relative Value Scale (RBRVS) under the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act. Medicare officials used the new RBRVS to establish a standardized physician payment schedule in 1992. Under the new system, payments were determined by calculating the costs of physician work, practice expenses, and professional liability insurance. Payments are then adjusted by a conversion factor and geographic cost differences.

“The impact of the fee schedule all depends on where you sit,” said Paul B. Ginsburg, Ph.D., director of health policy at the Schaeffer Center for Health Policy and Economics at the University of Southern California.

The fee schedule was positive for primary care physicians at first, but a flawed updating process over the decades led to differences in Medicare payments by specialty, largely favoring procedural specialists over those who billed for evaluation and management services.

But Dr. Ginsburg said Medicare is now on the cusp of an even more important payment change as federal officials begin to move away from fee-for-service and toward payment approaches that emphasize quality and value.

While some new payment model experiments have been promising, the attempts by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services have been “fumbling,” Dr. Ginsburg said.

Changing physician satisfaction

Medicare beneficiaries are typically happier with their health coverage than individuals enrolled in private, employer-sponsored insurance and are less worried about financial barriers to care, Dr. Guterman said.

“I think it’s fair to say that it’s one of the more popular federal programs ever,” he said. “You hear people frequently talking about how touchy it is to make any changes to the program because people are very wary of having that benefit diluted.”

That’s not the case for physicians.

“The physicians I’ve talked to over the last 2 years feel like they’re drowning in red tape,” said Dr. Austin King, president of the Texas Medical Association and a head and neck surgeon in Abilene.

The result is that physicians are becoming employees in large physician practices or hospitals, or they are moving to set up boutique practices, Dr. King said. “Right now, the physicians are not real happy with the program.”

Dr. King predicted that physicians will continue to move out of the program, creating patient access issues, unless Congress gives them a way to recoup their costs, such as through the practice of balance billing.

Resolving issues like the looming annual cuts from the Sustainable Growth Rate formula and eliminating the Affordable Care Act’s Independent Payment Advisory Board would put some predictability back into the system, Dr. King said, adding that it’s not enough because it would still leave the numerous regulatory requirements, which many physicians “agonize” over.

It’s that kind of agony that keeps Dr. Jane Orient, a general internist in Tucson, Ariz., from participating in Medicare. Dr. Orient opted out of the program in 1990, around the time that Medicare began requiring that physicians file claims for payment. Previously, patients could pay her directly for services and be reimbursed by Medicare.

“I decided I just could not do that,” said Dr. Orient, executive director of the Association of American Physicians and Surgeons. “For me to file the claim and figure out what all those E&M guidelines meant, was just impossible. I certainly couldn’t do it with the staff I had.”

The fundamental problem, said Rep. Michael C. Burgess (R-Texas), cochair of the Congressional Health Caucus and an ob.gyn., is that patients get their care covered at a price they can afford, while Medicare’s payment to physicians doesn’t cover the cost of care.

“What has always been a bad situation is getting worse and worse with every passing year,” Rep. Burgess said.

Rep. Phil Roe (R-Tenn.), cochair of the GOP Doctors Caucus, said the problem for lawmakers is that they must fix the physician payment system before patient access is significantly affected. How much time do they have?

Rep. Roe, an ob.gyn., said physicians will hang on for as long as they can. But if Medicare continues to cut payments, an access crisis is coming.

If Medicare’s solution to their financing problem is to cut providers, he said, physicians will look for a way out of the program, and that will start with large-scale retirements of older physicians.

“They are all looking for the exit signs now,” Rep. Roe said.

|

This is the first in a series of articles tracing the 50-year history of Medicare and its impact on physicians and patients. Future articles will focus on the public health impact of Medicare, the origins of the Sustainable Growth Rate formula, and the long-term financial viability of the program.

mschneider@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @maryellenny

When President Lyndon B. Johnson signed Medicare into law on July 30, 1965, he vowed that the program would give seniors access to the “healing miracle of modern medicine” and save them from exhausting their savings when they became ill.

For the most part, the program has delivered on those bold promises. Americans over age 65 years are living longer, healthier lives, and they are doing so without fear that a trip to the hospital will lead to bankruptcy. That security has only increased over time, as Congress added prescription drug coverage and most recently, free preventive care. In 1972, the Medicare program was extended to the long-term disabled and those with end stage renal disease.

Medicare “fundamentally changed the way we thought about health in our nation for our seniors,” said Dr. Georges C. Benjamin, executive director of the American Public Health Association. “This probably was the most important tool to lift seniors out of poverty. The economic benefit of this, in addition to the health benefit, was enormous.”

Along with coverage of hospital stays and physician services for seniors under Medicare, the Social Security Act Amendments of 1965 also created Medicaid, a voluntary federal-state partnership to provide medical care and long-term care services to low-income Americans.

Changing medical practice

When combined with the Civil Rights Act of 1964, Medicare desegregated all hospitals that participated in the program. Prior to the start of Medicare on July 1, 1966, a large number of hospitals around the country were still racially segregated in some manner. In many areas of the South, a separate hospital system served the black community and were the only places where black physicians could train and practice (Milbank Q. 2005; 83: 247-69). But in a matter of months, hospitals across the country integrated their facilities and staff in a relative peaceful manner, according to a study conducted by the Commonwealth Fund.

“Now, physicians of color could not be kept out of hospitals as a matter of policy,” Dr. Benjamin said. “It dramatically improved practice opportunities for physicians and access to care opportunities for patients.”

Stuart Guterman, Ph.D., vice president for Medicare and cost control at the Commonwealth Fund, said it’s one of the lesser-known elements of Medicare’s history that the law became an impetus to overcoming racial barriers for both patients and physicians.

Changing payment incentives

Medicare payments opened up a significant new stream of revenue for hospitals that made desegregation more palatable. But hospitals weren’t the only ones who benefited financially from the new program.

Despite the American Medical Association’s fight against the creation of Medicare, during which officials famously decried the program as “socialized medicine,” physicians were financial winners under the new law, at least at first.

Much like hospitals, doctors got paid for the first time for treating patients who they had previously seen as charity care. And, in those early years of the Medicare program, the government paid on a charge basis. The result was that Medicare spending was quickly out of control.

Cost controls were added first for hospital care. In 1983, Medicare adopted the inpatient hospital prospective payment system, which replaced hospitals’ cost-based payments with the diagnosis-related group (DRG) system.

“Changing the notion of what hospitals did from each individual service or each individual day to the hospital stay, really changed the way hospital care was looked at,” Dr. Guterman said.

It took somewhat longer for federal health officials to tackle payment on the physician side. Throughout the 1980s, Congress froze physician payment rates in an effort to address rising costs. In 1984, Congress established the Participating Physicians’ Program, which required physicians to accept assignment for all Medicare patients and services rather than on a service-by-service basis. It also barred balance billing of Medicare beneficiaries.

In 1989, Congress made the most significant change yet to physician payment, creating the Resource-Based Relative Value Scale (RBRVS) under the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act. Medicare officials used the new RBRVS to establish a standardized physician payment schedule in 1992. Under the new system, payments were determined by calculating the costs of physician work, practice expenses, and professional liability insurance. Payments are then adjusted by a conversion factor and geographic cost differences.

“The impact of the fee schedule all depends on where you sit,” said Paul B. Ginsburg, Ph.D., director of health policy at the Schaeffer Center for Health Policy and Economics at the University of Southern California.

The fee schedule was positive for primary care physicians at first, but a flawed updating process over the decades led to differences in Medicare payments by specialty, largely favoring procedural specialists over those who billed for evaluation and management services.

But Dr. Ginsburg said Medicare is now on the cusp of an even more important payment change as federal officials begin to move away from fee-for-service and toward payment approaches that emphasize quality and value.

While some new payment model experiments have been promising, the attempts by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services have been “fumbling,” Dr. Ginsburg said.

Changing physician satisfaction

Medicare beneficiaries are typically happier with their health coverage than individuals enrolled in private, employer-sponsored insurance and are less worried about financial barriers to care, Dr. Guterman said.

“I think it’s fair to say that it’s one of the more popular federal programs ever,” he said. “You hear people frequently talking about how touchy it is to make any changes to the program because people are very wary of having that benefit diluted.”

That’s not the case for physicians.

“The physicians I’ve talked to over the last 2 years feel like they’re drowning in red tape,” said Dr. Austin King, president of the Texas Medical Association and a head and neck surgeon in Abilene.

The result is that physicians are becoming employees in large physician practices or hospitals, or they are moving to set up boutique practices, Dr. King said. “Right now, the physicians are not real happy with the program.”

Dr. King predicted that physicians will continue to move out of the program, creating patient access issues, unless Congress gives them a way to recoup their costs, such as through the practice of balance billing.

Resolving issues like the looming annual cuts from the Sustainable Growth Rate formula and eliminating the Affordable Care Act’s Independent Payment Advisory Board would put some predictability back into the system, Dr. King said, adding that it’s not enough because it would still leave the numerous regulatory requirements, which many physicians “agonize” over.

It’s that kind of agony that keeps Dr. Jane Orient, a general internist in Tucson, Ariz., from participating in Medicare. Dr. Orient opted out of the program in 1990, around the time that Medicare began requiring that physicians file claims for payment. Previously, patients could pay her directly for services and be reimbursed by Medicare.

“I decided I just could not do that,” said Dr. Orient, executive director of the Association of American Physicians and Surgeons. “For me to file the claim and figure out what all those E&M guidelines meant, was just impossible. I certainly couldn’t do it with the staff I had.”

The fundamental problem, said Rep. Michael C. Burgess (R-Texas), cochair of the Congressional Health Caucus and an ob.gyn., is that patients get their care covered at a price they can afford, while Medicare’s payment to physicians doesn’t cover the cost of care.

“What has always been a bad situation is getting worse and worse with every passing year,” Rep. Burgess said.

Rep. Phil Roe (R-Tenn.), cochair of the GOP Doctors Caucus, said the problem for lawmakers is that they must fix the physician payment system before patient access is significantly affected. How much time do they have?

Rep. Roe, an ob.gyn., said physicians will hang on for as long as they can. But if Medicare continues to cut payments, an access crisis is coming.

If Medicare’s solution to their financing problem is to cut providers, he said, physicians will look for a way out of the program, and that will start with large-scale retirements of older physicians.

“They are all looking for the exit signs now,” Rep. Roe said.

|

This is the first in a series of articles tracing the 50-year history of Medicare and its impact on physicians and patients. Future articles will focus on the public health impact of Medicare, the origins of the Sustainable Growth Rate formula, and the long-term financial viability of the program.

mschneider@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @maryellenny

When President Lyndon B. Johnson signed Medicare into law on July 30, 1965, he vowed that the program would give seniors access to the “healing miracle of modern medicine” and save them from exhausting their savings when they became ill.

For the most part, the program has delivered on those bold promises. Americans over age 65 years are living longer, healthier lives, and they are doing so without fear that a trip to the hospital will lead to bankruptcy. That security has only increased over time, as Congress added prescription drug coverage and most recently, free preventive care. In 1972, the Medicare program was extended to the long-term disabled and those with end stage renal disease.

Medicare “fundamentally changed the way we thought about health in our nation for our seniors,” said Dr. Georges C. Benjamin, executive director of the American Public Health Association. “This probably was the most important tool to lift seniors out of poverty. The economic benefit of this, in addition to the health benefit, was enormous.”

Along with coverage of hospital stays and physician services for seniors under Medicare, the Social Security Act Amendments of 1965 also created Medicaid, a voluntary federal-state partnership to provide medical care and long-term care services to low-income Americans.

Changing medical practice

When combined with the Civil Rights Act of 1964, Medicare desegregated all hospitals that participated in the program. Prior to the start of Medicare on July 1, 1966, a large number of hospitals around the country were still racially segregated in some manner. In many areas of the South, a separate hospital system served the black community and were the only places where black physicians could train and practice (Milbank Q. 2005; 83: 247-69). But in a matter of months, hospitals across the country integrated their facilities and staff in a relative peaceful manner, according to a study conducted by the Commonwealth Fund.

“Now, physicians of color could not be kept out of hospitals as a matter of policy,” Dr. Benjamin said. “It dramatically improved practice opportunities for physicians and access to care opportunities for patients.”

Stuart Guterman, Ph.D., vice president for Medicare and cost control at the Commonwealth Fund, said it’s one of the lesser-known elements of Medicare’s history that the law became an impetus to overcoming racial barriers for both patients and physicians.

Changing payment incentives

Medicare payments opened up a significant new stream of revenue for hospitals that made desegregation more palatable. But hospitals weren’t the only ones who benefited financially from the new program.

Despite the American Medical Association’s fight against the creation of Medicare, during which officials famously decried the program as “socialized medicine,” physicians were financial winners under the new law, at least at first.

Much like hospitals, doctors got paid for the first time for treating patients who they had previously seen as charity care. And, in those early years of the Medicare program, the government paid on a charge basis. The result was that Medicare spending was quickly out of control.

Cost controls were added first for hospital care. In 1983, Medicare adopted the inpatient hospital prospective payment system, which replaced hospitals’ cost-based payments with the diagnosis-related group (DRG) system.

“Changing the notion of what hospitals did from each individual service or each individual day to the hospital stay, really changed the way hospital care was looked at,” Dr. Guterman said.

It took somewhat longer for federal health officials to tackle payment on the physician side. Throughout the 1980s, Congress froze physician payment rates in an effort to address rising costs. In 1984, Congress established the Participating Physicians’ Program, which required physicians to accept assignment for all Medicare patients and services rather than on a service-by-service basis. It also barred balance billing of Medicare beneficiaries.

In 1989, Congress made the most significant change yet to physician payment, creating the Resource-Based Relative Value Scale (RBRVS) under the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act. Medicare officials used the new RBRVS to establish a standardized physician payment schedule in 1992. Under the new system, payments were determined by calculating the costs of physician work, practice expenses, and professional liability insurance. Payments are then adjusted by a conversion factor and geographic cost differences.

“The impact of the fee schedule all depends on where you sit,” said Paul B. Ginsburg, Ph.D., director of health policy at the Schaeffer Center for Health Policy and Economics at the University of Southern California.

The fee schedule was positive for primary care physicians at first, but a flawed updating process over the decades led to differences in Medicare payments by specialty, largely favoring procedural specialists over those who billed for evaluation and management services.

But Dr. Ginsburg said Medicare is now on the cusp of an even more important payment change as federal officials begin to move away from fee-for-service and toward payment approaches that emphasize quality and value.

While some new payment model experiments have been promising, the attempts by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services have been “fumbling,” Dr. Ginsburg said.

Changing physician satisfaction

Medicare beneficiaries are typically happier with their health coverage than individuals enrolled in private, employer-sponsored insurance and are less worried about financial barriers to care, Dr. Guterman said.

“I think it’s fair to say that it’s one of the more popular federal programs ever,” he said. “You hear people frequently talking about how touchy it is to make any changes to the program because people are very wary of having that benefit diluted.”

That’s not the case for physicians.

“The physicians I’ve talked to over the last 2 years feel like they’re drowning in red tape,” said Dr. Austin King, president of the Texas Medical Association and a head and neck surgeon in Abilene.

The result is that physicians are becoming employees in large physician practices or hospitals, or they are moving to set up boutique practices, Dr. King said. “Right now, the physicians are not real happy with the program.”

Dr. King predicted that physicians will continue to move out of the program, creating patient access issues, unless Congress gives them a way to recoup their costs, such as through the practice of balance billing.

Resolving issues like the looming annual cuts from the Sustainable Growth Rate formula and eliminating the Affordable Care Act’s Independent Payment Advisory Board would put some predictability back into the system, Dr. King said, adding that it’s not enough because it would still leave the numerous regulatory requirements, which many physicians “agonize” over.

It’s that kind of agony that keeps Dr. Jane Orient, a general internist in Tucson, Ariz., from participating in Medicare. Dr. Orient opted out of the program in 1990, around the time that Medicare began requiring that physicians file claims for payment. Previously, patients could pay her directly for services and be reimbursed by Medicare.

“I decided I just could not do that,” said Dr. Orient, executive director of the Association of American Physicians and Surgeons. “For me to file the claim and figure out what all those E&M guidelines meant, was just impossible. I certainly couldn’t do it with the staff I had.”

The fundamental problem, said Rep. Michael C. Burgess (R-Texas), cochair of the Congressional Health Caucus and an ob.gyn., is that patients get their care covered at a price they can afford, while Medicare’s payment to physicians doesn’t cover the cost of care.

“What has always been a bad situation is getting worse and worse with every passing year,” Rep. Burgess said.

Rep. Phil Roe (R-Tenn.), cochair of the GOP Doctors Caucus, said the problem for lawmakers is that they must fix the physician payment system before patient access is significantly affected. How much time do they have?

Rep. Roe, an ob.gyn., said physicians will hang on for as long as they can. But if Medicare continues to cut payments, an access crisis is coming.

If Medicare’s solution to their financing problem is to cut providers, he said, physicians will look for a way out of the program, and that will start with large-scale retirements of older physicians.

“They are all looking for the exit signs now,” Rep. Roe said.

|

This is the first in a series of articles tracing the 50-year history of Medicare and its impact on physicians and patients. Future articles will focus on the public health impact of Medicare, the origins of the Sustainable Growth Rate formula, and the long-term financial viability of the program.

mschneider@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @maryellenny