User login

When infants are born, they have nearly a clean slate with regard to their immune systems. Virtually all their immune cells are naive. They have no immunity memory. Vaccines at birth, and in the first 2 years of life, elicit variable antibody levels and cellular immune responses. Sometimes, this leaves fully vaccinated children unprotected against vaccine-preventable infectious diseases.

Newborns are bombarded at birth with microbes and other antigenic stimuli from the environment; food in the form of breast milk, formula, water; and vaccines, such as hepatitis B and, in other countries, with BCG. At birth, to avoid immunologically-induced injury, immune responses favor immunologic tolerance. However, adaptation must be rapid to avoid life-threatening infections. To navigate the gauntlet of microbe and environmental exposures and vaccines, the neonatal immune system moves through a gradual maturation process toward immune responsivity. The maturation occurs at different rates in different children.

Reassessing Vaccine Responsiveness

Vaccine responsiveness is usually assessed by measuring antibody levels in blood. Until recently, it was thought to be “bad luck” when a child failed to develop protective immunity following vaccination. The bad luck was suggested to involve illness at the time of vaccination, especially illness occurring with fever, and especially common viral infections. But studies proved that notion incorrect. About 10 years ago I became more interested in variability in vaccine responses in the first 2 years of life. In 2016, my laboratory described a specific population of children with specific cellular immune deficiencies that we classified as low vaccine responders (LVRs).1 To preclude the suggestion that low vaccine responses were to be considered normal biological variation, we chose an a priori definition of LVR as those with sub-protective IgG antibody levels to four (≥ 66 %) of six tested vaccines in DTaP-Hib (diphtheria toxoid, tetanus toxoid, pertussis toxoid, pertactin, and filamentous hemagglutinin [DTaP] and Haemophilus influenzae type b polysaccharide capsule [Hib]). Antibody levels were measured at 1 year of age following primary vaccinations at child age 2, 4, and 6 months old. The remaining 89% of children we termed normal vaccine responders (NVRs). We additionally tested antibody responses to viral protein and pneumococcal polysaccharide conjugated antigens (polio serotypes 1, 2, and 3, hepatitis B, and Streptococcus pneumoniae capsular polysaccharides serotypes 6B, 14, and 23F). Responses to these vaccine antigens were similar to the six vaccines (DTaP/Hib) used to define LVR. We and other groups have used alternative definitions of low vaccine responses that rely on statistics.

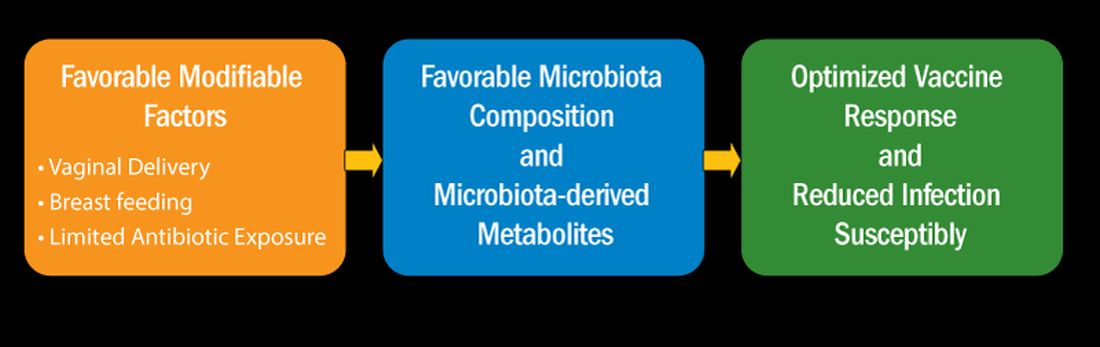

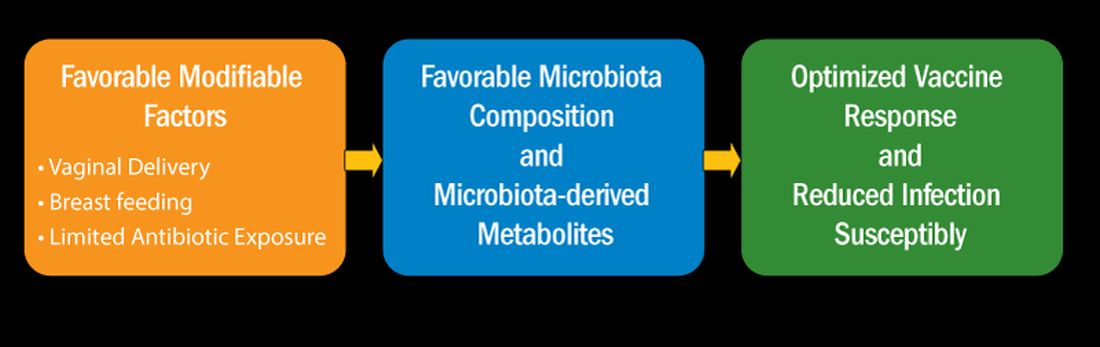

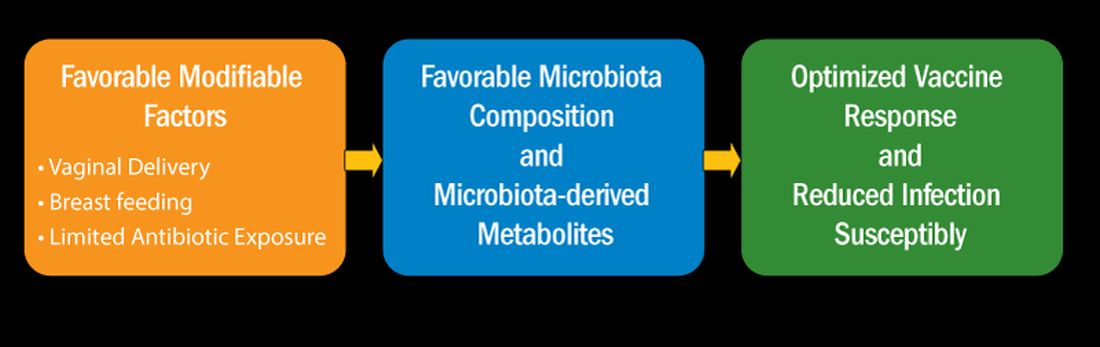

I recently reviewed the topic of the determinants of vaccine responses in early life, with a focus on the infant microbiome and metabolome: a.) cesarean section versus vaginal delivery, b.) breast versus formula feeding and c.) antibiotic exposure, that impact the immune response2 (Figure). In the review I also discussed how microbiome may serve as natural adjuvants for vaccine responses, how microbiota-derived metabolites influence vaccine responses, and how low vaccine responses in early life may be linked to increased infection susceptibility (Figure).

Cesarean section births occur in nearly 30% of newborns. Cesarean section birth has been associated with adverse effects on immune development, including predisposing to infections, allergies, and inflammatory disorders. The association of these adverse outcomes has been linked to lower total microbiome diversity. Fecal microbiome seeding from mother to infant in vaginal-delivered infants results in a more favorable and stable microbiome compared with cesarean-delivered infants. Nasopharyngeal microbiome may also be adversely affected by cesarean delivery. In turn, those microbiome differences can be linked to variation in vaccine responsiveness in infants.

Multiple studies strongly support the notion that breastfeeding has a favorable impact on immune development in early life associated with better vaccine responses, mediated by the microbiome. The mechanism of favorable immune responses to vaccines largely relates to the presence of a specific bacteria species, Bifidobacterium infantis. Breast milk contains human milk oligosaccharides that are not digestible by newborns. B. infantis is a strain of bacteria that utilizes these non-digestible oligosaccharides. Thereby, infants fed breast milk provides B. infantis the essential source of nutrition for its growth and predominance in the newborn gut. Studies have shown that Bifidobacterium spp. abundance in early life is correlated with better immune responses to multiple vaccines. Bifidobacterium spp. abundance has been positively correlated with antibody responses measured after 2 years, linking the microbiome composition to the durability of vaccine-induced immune responses.

Antibiotic exposure in early life may disproportionately damage the newborn and infant microbiome compared with later childhood. The average child receives about three antibiotic courses by the age of 2 years. My lab was among the first to describe the adverse effects of antibiotics on vaccine responses in early life.3 We found that broader spectrum antibiotics had a greater adverse effect on vaccine-induced antibody levels than narrower spectrum antibiotics. Ten-day versus five-day treatment courses had a greater negative effect. Multiple antibiotic courses over time (cumulative antibiotic exposure) was negatively associated with vaccine-induced antibody levels.

Over 11 % of live births worldwide occur preterm. Because bacterial infections are frequent complications of preterm birth, 79 % of very low birthweight and 87 % of extremely low birthweight infants in US NICUs receive antibiotics within 3 days of birth. Recently, my group studied full-term infants at birth and found that exposure to parenteral antibiotics at birth or during the first days of life had an adverse effect on vaccine responses.4

Microbiome Impacts Immunity

How does the microbiome affect immunity, and specifically vaccine responses? Microbial-derived metabolites affect host immunity. Gut bacteria produce short chain fatty acids (SCFAs: acetate, propionate, butyrate) [115]. SCFAs positively influence immunity cells. Vitamin D metabolites are generated by intestinal bacteria and those metabolites positively influence immunity. Secondary bile acids produced by Clostridium spp. are involved in favorable immune responses. Increased levels of phenylpyruvic acid produced by gut and/or nasopharyngeal microbiota correlate with reduced vaccine responses and upregulated metabolome genes that encode for oxidative phosphorylation correlate with increased vaccine responses.

In summary, immune development commences at birth. Impairment in responses to vaccination in children have been linked to disturbance in the microbiome. Cesarean section and absence of breastfeeding are associated with adverse microbiota composition. Antibiotics perturb healthy microbiota development. The microbiota affect immunity in several ways, among them are effects by metabolites generated by the commensals that inhabit the child host. A child who responds poorly to vaccines and has specific immune cell dysfunction caused by problems with the microbiome also displays increased infection proneness. But that is a story for another column, later.

Dr. Pichichero is a specialist in pediatric infectious diseases, Center for Infectious Diseases and Immunology, and director of the Research Institute, at Rochester (N.Y.) General Hospital. He has no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

1. Pichichero ME et al. J Infect Dis. 2016 Jun 15;213(12):2014-2019. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiw053.

2. Pichichero ME. Cell Immunol. 2023 Nov-Dec:393-394:104777. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2023.104777.

3. Chapman TJ et al. Pediatrics. 2022 May 1;149(5):e2021052061. doi: 10.1542/peds.2021-052061.

4. Shaffer M et al. mSystems. 2023 Oct 26;8(5):e0066123. doi: 10.1128/msystems.00661-23.

When infants are born, they have nearly a clean slate with regard to their immune systems. Virtually all their immune cells are naive. They have no immunity memory. Vaccines at birth, and in the first 2 years of life, elicit variable antibody levels and cellular immune responses. Sometimes, this leaves fully vaccinated children unprotected against vaccine-preventable infectious diseases.

Newborns are bombarded at birth with microbes and other antigenic stimuli from the environment; food in the form of breast milk, formula, water; and vaccines, such as hepatitis B and, in other countries, with BCG. At birth, to avoid immunologically-induced injury, immune responses favor immunologic tolerance. However, adaptation must be rapid to avoid life-threatening infections. To navigate the gauntlet of microbe and environmental exposures and vaccines, the neonatal immune system moves through a gradual maturation process toward immune responsivity. The maturation occurs at different rates in different children.

Reassessing Vaccine Responsiveness

Vaccine responsiveness is usually assessed by measuring antibody levels in blood. Until recently, it was thought to be “bad luck” when a child failed to develop protective immunity following vaccination. The bad luck was suggested to involve illness at the time of vaccination, especially illness occurring with fever, and especially common viral infections. But studies proved that notion incorrect. About 10 years ago I became more interested in variability in vaccine responses in the first 2 years of life. In 2016, my laboratory described a specific population of children with specific cellular immune deficiencies that we classified as low vaccine responders (LVRs).1 To preclude the suggestion that low vaccine responses were to be considered normal biological variation, we chose an a priori definition of LVR as those with sub-protective IgG antibody levels to four (≥ 66 %) of six tested vaccines in DTaP-Hib (diphtheria toxoid, tetanus toxoid, pertussis toxoid, pertactin, and filamentous hemagglutinin [DTaP] and Haemophilus influenzae type b polysaccharide capsule [Hib]). Antibody levels were measured at 1 year of age following primary vaccinations at child age 2, 4, and 6 months old. The remaining 89% of children we termed normal vaccine responders (NVRs). We additionally tested antibody responses to viral protein and pneumococcal polysaccharide conjugated antigens (polio serotypes 1, 2, and 3, hepatitis B, and Streptococcus pneumoniae capsular polysaccharides serotypes 6B, 14, and 23F). Responses to these vaccine antigens were similar to the six vaccines (DTaP/Hib) used to define LVR. We and other groups have used alternative definitions of low vaccine responses that rely on statistics.

I recently reviewed the topic of the determinants of vaccine responses in early life, with a focus on the infant microbiome and metabolome: a.) cesarean section versus vaginal delivery, b.) breast versus formula feeding and c.) antibiotic exposure, that impact the immune response2 (Figure). In the review I also discussed how microbiome may serve as natural adjuvants for vaccine responses, how microbiota-derived metabolites influence vaccine responses, and how low vaccine responses in early life may be linked to increased infection susceptibility (Figure).

Cesarean section births occur in nearly 30% of newborns. Cesarean section birth has been associated with adverse effects on immune development, including predisposing to infections, allergies, and inflammatory disorders. The association of these adverse outcomes has been linked to lower total microbiome diversity. Fecal microbiome seeding from mother to infant in vaginal-delivered infants results in a more favorable and stable microbiome compared with cesarean-delivered infants. Nasopharyngeal microbiome may also be adversely affected by cesarean delivery. In turn, those microbiome differences can be linked to variation in vaccine responsiveness in infants.

Multiple studies strongly support the notion that breastfeeding has a favorable impact on immune development in early life associated with better vaccine responses, mediated by the microbiome. The mechanism of favorable immune responses to vaccines largely relates to the presence of a specific bacteria species, Bifidobacterium infantis. Breast milk contains human milk oligosaccharides that are not digestible by newborns. B. infantis is a strain of bacteria that utilizes these non-digestible oligosaccharides. Thereby, infants fed breast milk provides B. infantis the essential source of nutrition for its growth and predominance in the newborn gut. Studies have shown that Bifidobacterium spp. abundance in early life is correlated with better immune responses to multiple vaccines. Bifidobacterium spp. abundance has been positively correlated with antibody responses measured after 2 years, linking the microbiome composition to the durability of vaccine-induced immune responses.

Antibiotic exposure in early life may disproportionately damage the newborn and infant microbiome compared with later childhood. The average child receives about three antibiotic courses by the age of 2 years. My lab was among the first to describe the adverse effects of antibiotics on vaccine responses in early life.3 We found that broader spectrum antibiotics had a greater adverse effect on vaccine-induced antibody levels than narrower spectrum antibiotics. Ten-day versus five-day treatment courses had a greater negative effect. Multiple antibiotic courses over time (cumulative antibiotic exposure) was negatively associated with vaccine-induced antibody levels.

Over 11 % of live births worldwide occur preterm. Because bacterial infections are frequent complications of preterm birth, 79 % of very low birthweight and 87 % of extremely low birthweight infants in US NICUs receive antibiotics within 3 days of birth. Recently, my group studied full-term infants at birth and found that exposure to parenteral antibiotics at birth or during the first days of life had an adverse effect on vaccine responses.4

Microbiome Impacts Immunity

How does the microbiome affect immunity, and specifically vaccine responses? Microbial-derived metabolites affect host immunity. Gut bacteria produce short chain fatty acids (SCFAs: acetate, propionate, butyrate) [115]. SCFAs positively influence immunity cells. Vitamin D metabolites are generated by intestinal bacteria and those metabolites positively influence immunity. Secondary bile acids produced by Clostridium spp. are involved in favorable immune responses. Increased levels of phenylpyruvic acid produced by gut and/or nasopharyngeal microbiota correlate with reduced vaccine responses and upregulated metabolome genes that encode for oxidative phosphorylation correlate with increased vaccine responses.

In summary, immune development commences at birth. Impairment in responses to vaccination in children have been linked to disturbance in the microbiome. Cesarean section and absence of breastfeeding are associated with adverse microbiota composition. Antibiotics perturb healthy microbiota development. The microbiota affect immunity in several ways, among them are effects by metabolites generated by the commensals that inhabit the child host. A child who responds poorly to vaccines and has specific immune cell dysfunction caused by problems with the microbiome also displays increased infection proneness. But that is a story for another column, later.

Dr. Pichichero is a specialist in pediatric infectious diseases, Center for Infectious Diseases and Immunology, and director of the Research Institute, at Rochester (N.Y.) General Hospital. He has no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

1. Pichichero ME et al. J Infect Dis. 2016 Jun 15;213(12):2014-2019. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiw053.

2. Pichichero ME. Cell Immunol. 2023 Nov-Dec:393-394:104777. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2023.104777.

3. Chapman TJ et al. Pediatrics. 2022 May 1;149(5):e2021052061. doi: 10.1542/peds.2021-052061.

4. Shaffer M et al. mSystems. 2023 Oct 26;8(5):e0066123. doi: 10.1128/msystems.00661-23.

When infants are born, they have nearly a clean slate with regard to their immune systems. Virtually all their immune cells are naive. They have no immunity memory. Vaccines at birth, and in the first 2 years of life, elicit variable antibody levels and cellular immune responses. Sometimes, this leaves fully vaccinated children unprotected against vaccine-preventable infectious diseases.

Newborns are bombarded at birth with microbes and other antigenic stimuli from the environment; food in the form of breast milk, formula, water; and vaccines, such as hepatitis B and, in other countries, with BCG. At birth, to avoid immunologically-induced injury, immune responses favor immunologic tolerance. However, adaptation must be rapid to avoid life-threatening infections. To navigate the gauntlet of microbe and environmental exposures and vaccines, the neonatal immune system moves through a gradual maturation process toward immune responsivity. The maturation occurs at different rates in different children.

Reassessing Vaccine Responsiveness

Vaccine responsiveness is usually assessed by measuring antibody levels in blood. Until recently, it was thought to be “bad luck” when a child failed to develop protective immunity following vaccination. The bad luck was suggested to involve illness at the time of vaccination, especially illness occurring with fever, and especially common viral infections. But studies proved that notion incorrect. About 10 years ago I became more interested in variability in vaccine responses in the first 2 years of life. In 2016, my laboratory described a specific population of children with specific cellular immune deficiencies that we classified as low vaccine responders (LVRs).1 To preclude the suggestion that low vaccine responses were to be considered normal biological variation, we chose an a priori definition of LVR as those with sub-protective IgG antibody levels to four (≥ 66 %) of six tested vaccines in DTaP-Hib (diphtheria toxoid, tetanus toxoid, pertussis toxoid, pertactin, and filamentous hemagglutinin [DTaP] and Haemophilus influenzae type b polysaccharide capsule [Hib]). Antibody levels were measured at 1 year of age following primary vaccinations at child age 2, 4, and 6 months old. The remaining 89% of children we termed normal vaccine responders (NVRs). We additionally tested antibody responses to viral protein and pneumococcal polysaccharide conjugated antigens (polio serotypes 1, 2, and 3, hepatitis B, and Streptococcus pneumoniae capsular polysaccharides serotypes 6B, 14, and 23F). Responses to these vaccine antigens were similar to the six vaccines (DTaP/Hib) used to define LVR. We and other groups have used alternative definitions of low vaccine responses that rely on statistics.

I recently reviewed the topic of the determinants of vaccine responses in early life, with a focus on the infant microbiome and metabolome: a.) cesarean section versus vaginal delivery, b.) breast versus formula feeding and c.) antibiotic exposure, that impact the immune response2 (Figure). In the review I also discussed how microbiome may serve as natural adjuvants for vaccine responses, how microbiota-derived metabolites influence vaccine responses, and how low vaccine responses in early life may be linked to increased infection susceptibility (Figure).

Cesarean section births occur in nearly 30% of newborns. Cesarean section birth has been associated with adverse effects on immune development, including predisposing to infections, allergies, and inflammatory disorders. The association of these adverse outcomes has been linked to lower total microbiome diversity. Fecal microbiome seeding from mother to infant in vaginal-delivered infants results in a more favorable and stable microbiome compared with cesarean-delivered infants. Nasopharyngeal microbiome may also be adversely affected by cesarean delivery. In turn, those microbiome differences can be linked to variation in vaccine responsiveness in infants.

Multiple studies strongly support the notion that breastfeeding has a favorable impact on immune development in early life associated with better vaccine responses, mediated by the microbiome. The mechanism of favorable immune responses to vaccines largely relates to the presence of a specific bacteria species, Bifidobacterium infantis. Breast milk contains human milk oligosaccharides that are not digestible by newborns. B. infantis is a strain of bacteria that utilizes these non-digestible oligosaccharides. Thereby, infants fed breast milk provides B. infantis the essential source of nutrition for its growth and predominance in the newborn gut. Studies have shown that Bifidobacterium spp. abundance in early life is correlated with better immune responses to multiple vaccines. Bifidobacterium spp. abundance has been positively correlated with antibody responses measured after 2 years, linking the microbiome composition to the durability of vaccine-induced immune responses.

Antibiotic exposure in early life may disproportionately damage the newborn and infant microbiome compared with later childhood. The average child receives about three antibiotic courses by the age of 2 years. My lab was among the first to describe the adverse effects of antibiotics on vaccine responses in early life.3 We found that broader spectrum antibiotics had a greater adverse effect on vaccine-induced antibody levels than narrower spectrum antibiotics. Ten-day versus five-day treatment courses had a greater negative effect. Multiple antibiotic courses over time (cumulative antibiotic exposure) was negatively associated with vaccine-induced antibody levels.

Over 11 % of live births worldwide occur preterm. Because bacterial infections are frequent complications of preterm birth, 79 % of very low birthweight and 87 % of extremely low birthweight infants in US NICUs receive antibiotics within 3 days of birth. Recently, my group studied full-term infants at birth and found that exposure to parenteral antibiotics at birth or during the first days of life had an adverse effect on vaccine responses.4

Microbiome Impacts Immunity

How does the microbiome affect immunity, and specifically vaccine responses? Microbial-derived metabolites affect host immunity. Gut bacteria produce short chain fatty acids (SCFAs: acetate, propionate, butyrate) [115]. SCFAs positively influence immunity cells. Vitamin D metabolites are generated by intestinal bacteria and those metabolites positively influence immunity. Secondary bile acids produced by Clostridium spp. are involved in favorable immune responses. Increased levels of phenylpyruvic acid produced by gut and/or nasopharyngeal microbiota correlate with reduced vaccine responses and upregulated metabolome genes that encode for oxidative phosphorylation correlate with increased vaccine responses.

In summary, immune development commences at birth. Impairment in responses to vaccination in children have been linked to disturbance in the microbiome. Cesarean section and absence of breastfeeding are associated with adverse microbiota composition. Antibiotics perturb healthy microbiota development. The microbiota affect immunity in several ways, among them are effects by metabolites generated by the commensals that inhabit the child host. A child who responds poorly to vaccines and has specific immune cell dysfunction caused by problems with the microbiome also displays increased infection proneness. But that is a story for another column, later.

Dr. Pichichero is a specialist in pediatric infectious diseases, Center for Infectious Diseases and Immunology, and director of the Research Institute, at Rochester (N.Y.) General Hospital. He has no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

1. Pichichero ME et al. J Infect Dis. 2016 Jun 15;213(12):2014-2019. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiw053.

2. Pichichero ME. Cell Immunol. 2023 Nov-Dec:393-394:104777. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2023.104777.

3. Chapman TJ et al. Pediatrics. 2022 May 1;149(5):e2021052061. doi: 10.1542/peds.2021-052061.

4. Shaffer M et al. mSystems. 2023 Oct 26;8(5):e0066123. doi: 10.1128/msystems.00661-23.