User login

NEW YORK – Just as an imbalance in the intestinal microbiota can disrupt gut function, dysbiosis of the facial skin can allow acne-causing bacteria to flourish.

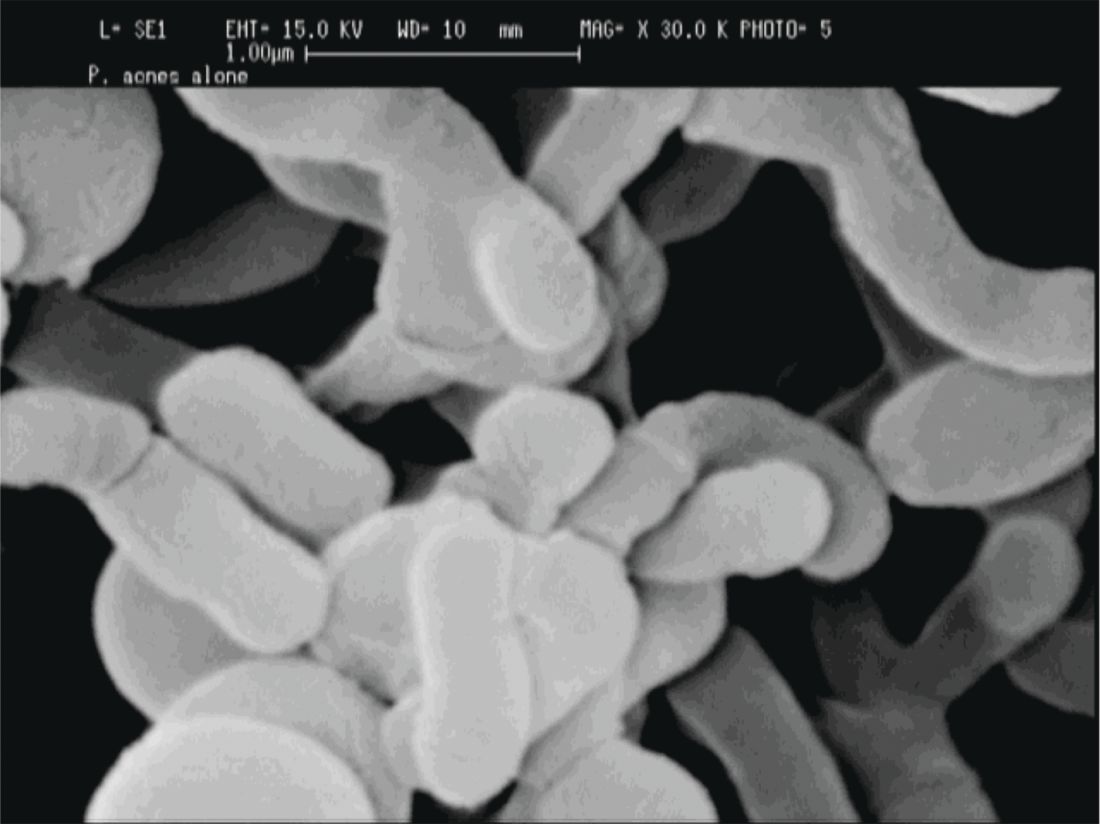

In acne, said Adam Friedman, MD, “we’ve always been talking about bacteria,” but now the thinking has shifted from just controlling Propionibacterium acnes to a subtler understanding of what’s happening on the skin of individuals with acne. Individuals may have their own unique skin microbiota – the community of organisms resident on the skin – but dysbiosis characterized by a lack of diversity is increasingly understood as a common theme in many skin disorders, and acne is no exception.

As in many other areas of medicine, dermatology’s understanding has been informed by genetic work that moves beyond the human genome. “Using newer technology, we were able to identify that our genome really was overshadowed by the microbial genome that makes up the populations in our skin, in our gut, and what have you,” said Dr. Friedman, speaking at the summer meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology.

The human body is like a planet to the bacteria that live on the human skin, and like a planet, the skin provides multiple “climates” for many bacterial ecosystems, said Dr. Friedman, director of translational research and dermatology residency program director, at George Washington University, Washington, DC.

Some areas are dry, some are moist; some are more oily, and some areas of the skin produce little sebum; while some are mostly dark and some are more likely to be exposed to light.

Considering skin from this perspective, it makes sense that bacterial microbiota for these disparate areas varies widely, with a different mix of bacteria found in the groin than on the forearm, he noted. Further, “each individual has his or her own microbiota fingerprint,” said Dr. Friedman, citing a 2012 study showing that in four healthy volunteers, the microbiota from swabs at four sites (antecubital fossa, back, nare, and plantar heel) varied widely both in diversity and composition (Genome Res. 2012 May;22[5]:850-9).

Multiple factors can contribute to this variability, which can include endogenous factors, such as host genotype, sex, age, immune system, and pathobiology. Exogenous factors, such as climate, geographic location, and occupational exposures, also play a part.

Increasingly, said Dr. Friedman, lack of bacterial diversity in skin microbiota is recognized as an important factor in many disease states, including atopic dermatitis and psoriasis. And bacterial diversity has recently been shown to be reduced on the facial skin of patients with acne, even on areas of clear skin.

When acne treatments work, a healthy facial microbiota is restored. And perhaps counterintuitively, patients with acne who receive isotretinoin and antibiotics have much greater diversity in the microbiota of their facial skin after treatment than before, according to a study recently published online (Exp Dermatol. 2017 Jun 21. doi: 10.1111/exd.13397).

For now, this is still a chicken-and-egg situation, Dr. Friedman said. “Does the disease cause the lack of diversity, or does the lack of diversity cause the disease to develop? We don’t know yet.” (Nat Rev Microbiol. 2011 Apr;9[4]:244-53).

“If we’re going to think about the surface of our skin as a barrier, we must consider the microbiota as part of that barrier.”

P. acnes “is a clear instigator in eliciting a host inflammatory response,” through its recognition by toll-like receptors and the inflammasome to induce inflammation, Dr. Friedman said. However, it can also help prevent the colonization of opportunistic pathogens, including methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus pyogenes by helping maintain an acidic skin pH. “When and how does a commensal [organism] become a pathogen?” he asked.

The fact that P. acnes is a commensal bacterium on healthy skin seems to muddy the picture, until one also recognizes that there are different strains of P. acnes. Only some of these phylotypes cause acne, with an exaggerated host inflammatory response being one possible causative factor, noted Dr. Friedman.

A clue to how this occurs comes from a recent study that found that some types of P. acnes actually convert sebum to short-chain fatty acids that “interfere with how our bodies regulate toll-like receptors, uncoupling them and then laying them loose to create inflammation,” said Dr. Friedman (Sci Immunol. 2016 Oct 28;1[4]. pii: eaah4609).

When considering what to do with the available information, something for dermatologists to consider is the effect moisturizers have on the skin of patients with acne, Dr. Friedman said. A moisturizer contains water; it may also contain a carbon source in the form of a sugar like mannose, nitrogen in the form of amino acids, and some oligoelements such as calcium, magnesium, manganese, strontium, and selenium. All of these ingredients really serve as prebiotics for the skin microbiota, Dr. Friedman noted, adding that products that create a prebiotic environment where acnegenic P. acnes are suppressed and a healthy microbiota can flourish are being developed.

“What does all this mean? We do not know yet,” said Dr. Friedman. But, he added, “clearly, what we’re using is having an effect, and we need to figure it out.”

Dr. Friedman reported financial relationships with several pharmaceutical and skin care companies. He serves on the editorial board of Dermatology News.

koakes@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @karioakes

NEW YORK – Just as an imbalance in the intestinal microbiota can disrupt gut function, dysbiosis of the facial skin can allow acne-causing bacteria to flourish.

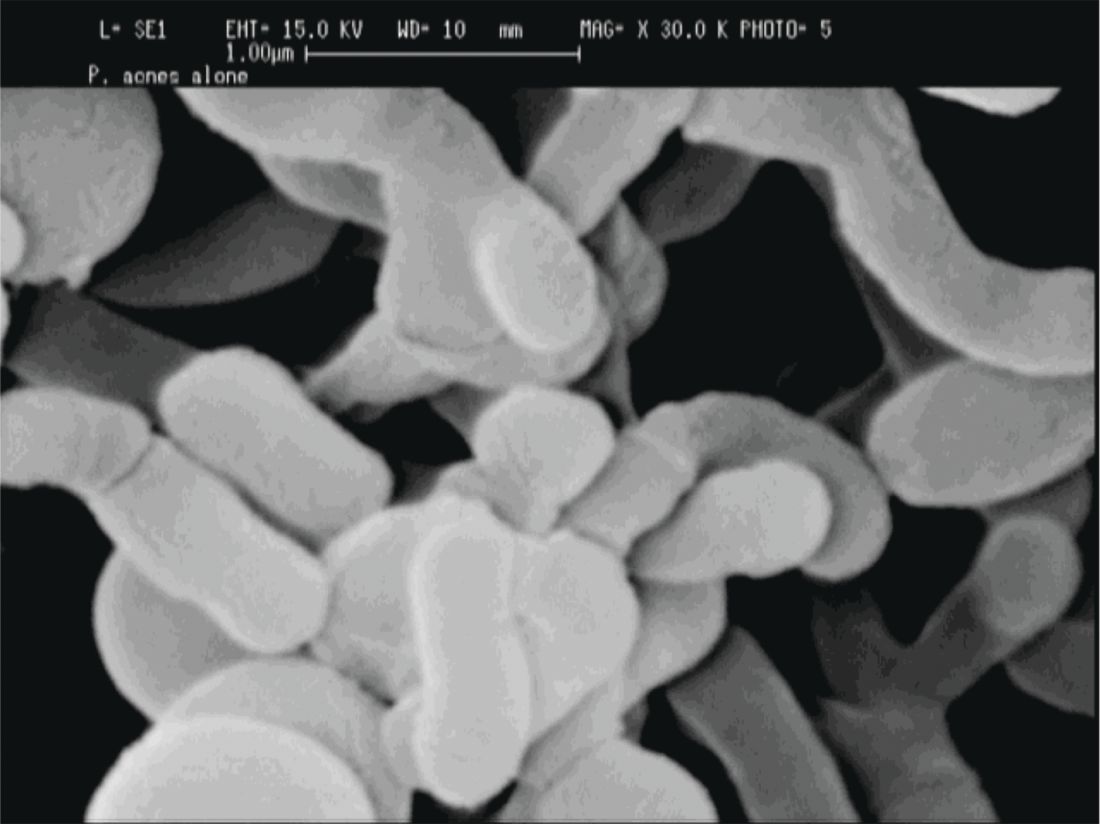

In acne, said Adam Friedman, MD, “we’ve always been talking about bacteria,” but now the thinking has shifted from just controlling Propionibacterium acnes to a subtler understanding of what’s happening on the skin of individuals with acne. Individuals may have their own unique skin microbiota – the community of organisms resident on the skin – but dysbiosis characterized by a lack of diversity is increasingly understood as a common theme in many skin disorders, and acne is no exception.

As in many other areas of medicine, dermatology’s understanding has been informed by genetic work that moves beyond the human genome. “Using newer technology, we were able to identify that our genome really was overshadowed by the microbial genome that makes up the populations in our skin, in our gut, and what have you,” said Dr. Friedman, speaking at the summer meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology.

The human body is like a planet to the bacteria that live on the human skin, and like a planet, the skin provides multiple “climates” for many bacterial ecosystems, said Dr. Friedman, director of translational research and dermatology residency program director, at George Washington University, Washington, DC.

Some areas are dry, some are moist; some are more oily, and some areas of the skin produce little sebum; while some are mostly dark and some are more likely to be exposed to light.

Considering skin from this perspective, it makes sense that bacterial microbiota for these disparate areas varies widely, with a different mix of bacteria found in the groin than on the forearm, he noted. Further, “each individual has his or her own microbiota fingerprint,” said Dr. Friedman, citing a 2012 study showing that in four healthy volunteers, the microbiota from swabs at four sites (antecubital fossa, back, nare, and plantar heel) varied widely both in diversity and composition (Genome Res. 2012 May;22[5]:850-9).

Multiple factors can contribute to this variability, which can include endogenous factors, such as host genotype, sex, age, immune system, and pathobiology. Exogenous factors, such as climate, geographic location, and occupational exposures, also play a part.

Increasingly, said Dr. Friedman, lack of bacterial diversity in skin microbiota is recognized as an important factor in many disease states, including atopic dermatitis and psoriasis. And bacterial diversity has recently been shown to be reduced on the facial skin of patients with acne, even on areas of clear skin.

When acne treatments work, a healthy facial microbiota is restored. And perhaps counterintuitively, patients with acne who receive isotretinoin and antibiotics have much greater diversity in the microbiota of their facial skin after treatment than before, according to a study recently published online (Exp Dermatol. 2017 Jun 21. doi: 10.1111/exd.13397).

For now, this is still a chicken-and-egg situation, Dr. Friedman said. “Does the disease cause the lack of diversity, or does the lack of diversity cause the disease to develop? We don’t know yet.” (Nat Rev Microbiol. 2011 Apr;9[4]:244-53).

“If we’re going to think about the surface of our skin as a barrier, we must consider the microbiota as part of that barrier.”

P. acnes “is a clear instigator in eliciting a host inflammatory response,” through its recognition by toll-like receptors and the inflammasome to induce inflammation, Dr. Friedman said. However, it can also help prevent the colonization of opportunistic pathogens, including methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus pyogenes by helping maintain an acidic skin pH. “When and how does a commensal [organism] become a pathogen?” he asked.

The fact that P. acnes is a commensal bacterium on healthy skin seems to muddy the picture, until one also recognizes that there are different strains of P. acnes. Only some of these phylotypes cause acne, with an exaggerated host inflammatory response being one possible causative factor, noted Dr. Friedman.

A clue to how this occurs comes from a recent study that found that some types of P. acnes actually convert sebum to short-chain fatty acids that “interfere with how our bodies regulate toll-like receptors, uncoupling them and then laying them loose to create inflammation,” said Dr. Friedman (Sci Immunol. 2016 Oct 28;1[4]. pii: eaah4609).

When considering what to do with the available information, something for dermatologists to consider is the effect moisturizers have on the skin of patients with acne, Dr. Friedman said. A moisturizer contains water; it may also contain a carbon source in the form of a sugar like mannose, nitrogen in the form of amino acids, and some oligoelements such as calcium, magnesium, manganese, strontium, and selenium. All of these ingredients really serve as prebiotics for the skin microbiota, Dr. Friedman noted, adding that products that create a prebiotic environment where acnegenic P. acnes are suppressed and a healthy microbiota can flourish are being developed.

“What does all this mean? We do not know yet,” said Dr. Friedman. But, he added, “clearly, what we’re using is having an effect, and we need to figure it out.”

Dr. Friedman reported financial relationships with several pharmaceutical and skin care companies. He serves on the editorial board of Dermatology News.

koakes@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @karioakes

NEW YORK – Just as an imbalance in the intestinal microbiota can disrupt gut function, dysbiosis of the facial skin can allow acne-causing bacteria to flourish.

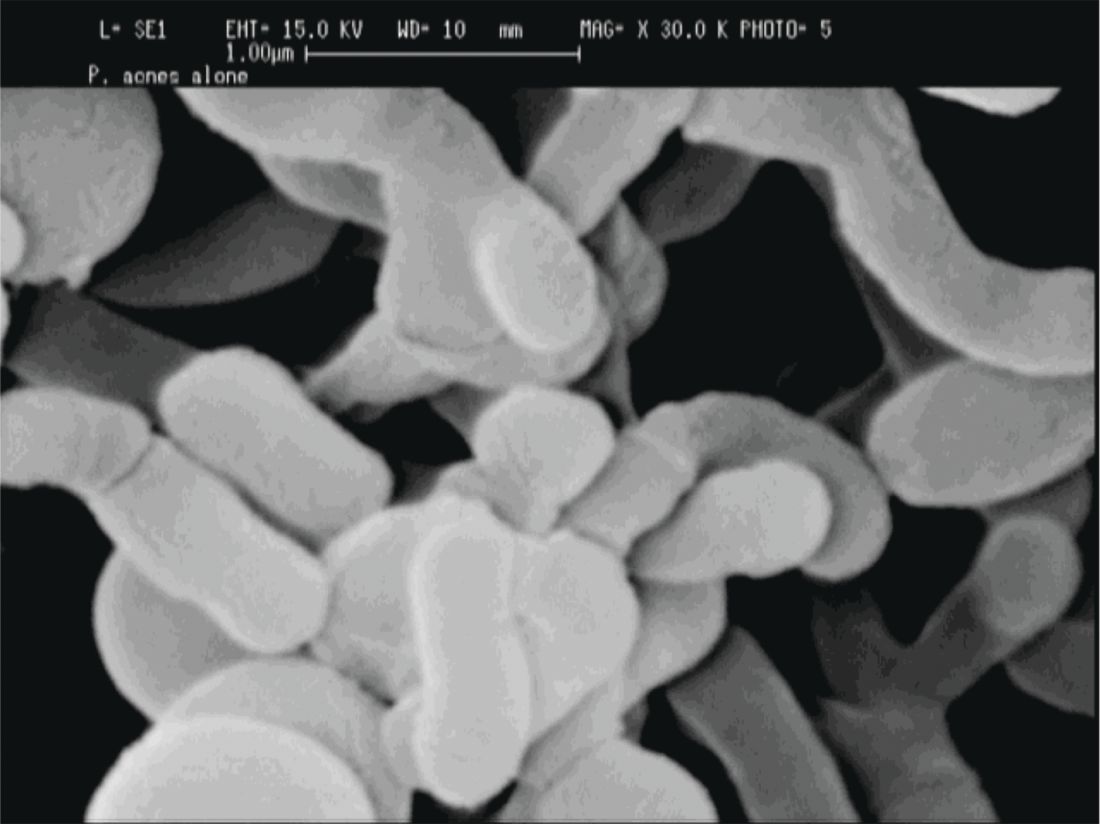

In acne, said Adam Friedman, MD, “we’ve always been talking about bacteria,” but now the thinking has shifted from just controlling Propionibacterium acnes to a subtler understanding of what’s happening on the skin of individuals with acne. Individuals may have their own unique skin microbiota – the community of organisms resident on the skin – but dysbiosis characterized by a lack of diversity is increasingly understood as a common theme in many skin disorders, and acne is no exception.

As in many other areas of medicine, dermatology’s understanding has been informed by genetic work that moves beyond the human genome. “Using newer technology, we were able to identify that our genome really was overshadowed by the microbial genome that makes up the populations in our skin, in our gut, and what have you,” said Dr. Friedman, speaking at the summer meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology.

The human body is like a planet to the bacteria that live on the human skin, and like a planet, the skin provides multiple “climates” for many bacterial ecosystems, said Dr. Friedman, director of translational research and dermatology residency program director, at George Washington University, Washington, DC.

Some areas are dry, some are moist; some are more oily, and some areas of the skin produce little sebum; while some are mostly dark and some are more likely to be exposed to light.

Considering skin from this perspective, it makes sense that bacterial microbiota for these disparate areas varies widely, with a different mix of bacteria found in the groin than on the forearm, he noted. Further, “each individual has his or her own microbiota fingerprint,” said Dr. Friedman, citing a 2012 study showing that in four healthy volunteers, the microbiota from swabs at four sites (antecubital fossa, back, nare, and plantar heel) varied widely both in diversity and composition (Genome Res. 2012 May;22[5]:850-9).

Multiple factors can contribute to this variability, which can include endogenous factors, such as host genotype, sex, age, immune system, and pathobiology. Exogenous factors, such as climate, geographic location, and occupational exposures, also play a part.

Increasingly, said Dr. Friedman, lack of bacterial diversity in skin microbiota is recognized as an important factor in many disease states, including atopic dermatitis and psoriasis. And bacterial diversity has recently been shown to be reduced on the facial skin of patients with acne, even on areas of clear skin.

When acne treatments work, a healthy facial microbiota is restored. And perhaps counterintuitively, patients with acne who receive isotretinoin and antibiotics have much greater diversity in the microbiota of their facial skin after treatment than before, according to a study recently published online (Exp Dermatol. 2017 Jun 21. doi: 10.1111/exd.13397).

For now, this is still a chicken-and-egg situation, Dr. Friedman said. “Does the disease cause the lack of diversity, or does the lack of diversity cause the disease to develop? We don’t know yet.” (Nat Rev Microbiol. 2011 Apr;9[4]:244-53).

“If we’re going to think about the surface of our skin as a barrier, we must consider the microbiota as part of that barrier.”

P. acnes “is a clear instigator in eliciting a host inflammatory response,” through its recognition by toll-like receptors and the inflammasome to induce inflammation, Dr. Friedman said. However, it can also help prevent the colonization of opportunistic pathogens, including methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus pyogenes by helping maintain an acidic skin pH. “When and how does a commensal [organism] become a pathogen?” he asked.

The fact that P. acnes is a commensal bacterium on healthy skin seems to muddy the picture, until one also recognizes that there are different strains of P. acnes. Only some of these phylotypes cause acne, with an exaggerated host inflammatory response being one possible causative factor, noted Dr. Friedman.

A clue to how this occurs comes from a recent study that found that some types of P. acnes actually convert sebum to short-chain fatty acids that “interfere with how our bodies regulate toll-like receptors, uncoupling them and then laying them loose to create inflammation,” said Dr. Friedman (Sci Immunol. 2016 Oct 28;1[4]. pii: eaah4609).

When considering what to do with the available information, something for dermatologists to consider is the effect moisturizers have on the skin of patients with acne, Dr. Friedman said. A moisturizer contains water; it may also contain a carbon source in the form of a sugar like mannose, nitrogen in the form of amino acids, and some oligoelements such as calcium, magnesium, manganese, strontium, and selenium. All of these ingredients really serve as prebiotics for the skin microbiota, Dr. Friedman noted, adding that products that create a prebiotic environment where acnegenic P. acnes are suppressed and a healthy microbiota can flourish are being developed.

“What does all this mean? We do not know yet,” said Dr. Friedman. But, he added, “clearly, what we’re using is having an effect, and we need to figure it out.”

Dr. Friedman reported financial relationships with several pharmaceutical and skin care companies. He serves on the editorial board of Dermatology News.

koakes@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @karioakes

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE 2017 AAD SUMMER MEETING