User login

Nail biopsies made simple

CHICAGO – Maral Skelsey, MD, doesn’t get flowers from her patients very often. But, she said, a big bouquet recently landed on her desk after she had performed a nail biopsy on a patient. The note from the patient read, “That wasn’t as bad as I thought it would be!”

The patient’s relief after the procedure highlights the apprehension that both patients and dermatologists can feel when a nail biopsy becomes necessary, said Dr. Skelsey, director of dermatologic surgery at Georgetown University, Washington, D.C.

Speaking at the summer meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology, Dr. Skelsey said that the most important advice she can give about the nail biopsy is, “Do it early and often.”

Dr. Skelsey reminded the audience that the musician Bob Marley died of malignant melanoma; the first sign of his cancer was a longitudinal melanonychia that went unbiopsied. “The biggest mistake we make is not doing it,” she said.

In performing a nail biopsy, said Dr. Skelsey, the goals are, first and foremost, to optimize the pathologic diagnosis. Correct technique can help avoid complications such as bleeding, infection, and nail dystrophy; the right approach can minimize pain and anxiety, she added.

In preparing for a biopsy for melanonychia, “dermoscopy can be very helpful” in assessing the location of the pigment and fine-tuning planning for the biopsy, said Dr. Skelsey. Also, if the streak of melanonychia has reached the distal nail, sending the clipping for pathology can be useful as well.

For dorsal pigmentation, the proximal nail matrix should be biopsied.

“Do not use a punch biopsy on the nail fold to diagnose melanoma – you will get a false negative,” Dr. Skelsey said. It’s not possible to get an accurate diagnosis going through the nail plate to the nail bed, she said.

The preoperative assessment is usually straightforward. Pertinent items in the patient’s history include any medication allergies, current anticoagulation, and any history of prior trauma to the digit to be biopsied. Occasionally, imaging may be helpful, and patients should always be assessed for vascular insufficiency, she noted.

Preoperatively, she asks her patients to remove nail polish and pretreat the area with povidone iodine for 2 days prior to the procedure. Patients need to have a ride home after the procedure, and should be prepared to elevate the affected extremity for 48 hours post procedure. If a toenail is biopsied, they’re advised to come with a postop shoe.

Her patients receive a 5-minute isopropyl alcohol wash of the area to be biopsied just before the procedure, followed by air drying and a 5-minute scrub with 7.5% povidone iodine, which then is wiped off preprocedure.

For hemostasis, a tourniquet can be improvised with a sterile glove finger and a hemostat; there are also dedicated finger cots available that work well for this purpose, she said. In addition to nail nippers and a nail elevator, an English nail splitter can be helpful, said Dr. Skelsey.

For anesthesia, she said she ordinarily uses a 30 gauge needle with buffered lidocaine and epinephrine at room temperature to deliver a wing block. Beginning about 1 cm proximal and lateral to the junction of the proximal and lateral nail fold, the dermatologist can slowly inject about 1.5 cc per side. As the block takes effect, the lateral nail fold will blanch distally in a wing-shaped pattern. This technique, she said, also has the benefit of acting as a volumetric tourniquet.

“To avulse or not to avulse?” asked Dr. Skelsey. “I used to avulse almost everything,” she said, but noted that a complete avulsion is a “pretty traumatic” procedure. Now, unless a full avulsion is required for complete and accurate pathology, she will usually perform a partial nail plate avulsion.

A partial avulsion can reduce pain and morbidity, and can be done by two different methods: the partial proximal avulsion, and the “trap door” avulsion. In a trap door avulsion, she said, the distal matrix is primarily visualized, so this may be a good option for a longitudinal melanonychia arising from the distal matrix. A Freer elevator is used to detach the nail plate from the bed and the matrix, after which the nail plate can be lifted with a hemostat.

In a partial proximal avulsion, the proximal nail fold is reflected, so it’s a better option when the proximal nail matrix needs evaluation, she said.

After the avulsion has been done, “the matrix has been exposed. Now what? Punch or shave?” asked Dr. Skelsey. She noted that she used to perform punch biopsies on “everything,” and that it’s a good option if the pigmented area spans 3 mm or less. One issue, though, is that the specimen can get stuck in the puncher, and extraction can make it difficult to deliver an intact specimen.

Shave biopsies, Dr. Skelsey said, are effective in dealing with nail matrix lesions. They can yield an accurate pathologic diagnosis, and the biopsied digits healed without nail dystrophy in about three quarters of the cases in one study, she said. Potential recurrence of pigmentation is one drawback of the shave technique, she said.

With a shave biopsy, she performs tangential incisions of the proximal and lateral nail folds, and scores and reflects the nail. Then, the band of pigment is shaved tangentially. She cauterizes the area, and sometimes will use a bit of an absorbable gelatin sponge (Gelfoam) as well. Then the proximal nail fold and nail plate are sutured.

Replacing the nail plate results in better cosmesis and is much more comfortable for the patient, she said. An 18-gauge needle can be used to bore a hole through the avulsed nail plate, which may be held in an antiseptic solution soak during the biopsy. The sutures should then be placed from skin to nail plate, so nail fragments aren’t driven into the skin during the suturing process. Finally, specimen margins should be inked, and separate labeled formalin jars are needed for the nail plate, nail bed, and the matrix.

Dr. Skelsey reported that she had no conflicts of interest.

koakes@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @karioakes

CHICAGO – Maral Skelsey, MD, doesn’t get flowers from her patients very often. But, she said, a big bouquet recently landed on her desk after she had performed a nail biopsy on a patient. The note from the patient read, “That wasn’t as bad as I thought it would be!”

The patient’s relief after the procedure highlights the apprehension that both patients and dermatologists can feel when a nail biopsy becomes necessary, said Dr. Skelsey, director of dermatologic surgery at Georgetown University, Washington, D.C.

Speaking at the summer meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology, Dr. Skelsey said that the most important advice she can give about the nail biopsy is, “Do it early and often.”

Dr. Skelsey reminded the audience that the musician Bob Marley died of malignant melanoma; the first sign of his cancer was a longitudinal melanonychia that went unbiopsied. “The biggest mistake we make is not doing it,” she said.

In performing a nail biopsy, said Dr. Skelsey, the goals are, first and foremost, to optimize the pathologic diagnosis. Correct technique can help avoid complications such as bleeding, infection, and nail dystrophy; the right approach can minimize pain and anxiety, she added.

In preparing for a biopsy for melanonychia, “dermoscopy can be very helpful” in assessing the location of the pigment and fine-tuning planning for the biopsy, said Dr. Skelsey. Also, if the streak of melanonychia has reached the distal nail, sending the clipping for pathology can be useful as well.

For dorsal pigmentation, the proximal nail matrix should be biopsied.

“Do not use a punch biopsy on the nail fold to diagnose melanoma – you will get a false negative,” Dr. Skelsey said. It’s not possible to get an accurate diagnosis going through the nail plate to the nail bed, she said.

The preoperative assessment is usually straightforward. Pertinent items in the patient’s history include any medication allergies, current anticoagulation, and any history of prior trauma to the digit to be biopsied. Occasionally, imaging may be helpful, and patients should always be assessed for vascular insufficiency, she noted.

Preoperatively, she asks her patients to remove nail polish and pretreat the area with povidone iodine for 2 days prior to the procedure. Patients need to have a ride home after the procedure, and should be prepared to elevate the affected extremity for 48 hours post procedure. If a toenail is biopsied, they’re advised to come with a postop shoe.

Her patients receive a 5-minute isopropyl alcohol wash of the area to be biopsied just before the procedure, followed by air drying and a 5-minute scrub with 7.5% povidone iodine, which then is wiped off preprocedure.

For hemostasis, a tourniquet can be improvised with a sterile glove finger and a hemostat; there are also dedicated finger cots available that work well for this purpose, she said. In addition to nail nippers and a nail elevator, an English nail splitter can be helpful, said Dr. Skelsey.

For anesthesia, she said she ordinarily uses a 30 gauge needle with buffered lidocaine and epinephrine at room temperature to deliver a wing block. Beginning about 1 cm proximal and lateral to the junction of the proximal and lateral nail fold, the dermatologist can slowly inject about 1.5 cc per side. As the block takes effect, the lateral nail fold will blanch distally in a wing-shaped pattern. This technique, she said, also has the benefit of acting as a volumetric tourniquet.

“To avulse or not to avulse?” asked Dr. Skelsey. “I used to avulse almost everything,” she said, but noted that a complete avulsion is a “pretty traumatic” procedure. Now, unless a full avulsion is required for complete and accurate pathology, she will usually perform a partial nail plate avulsion.

A partial avulsion can reduce pain and morbidity, and can be done by two different methods: the partial proximal avulsion, and the “trap door” avulsion. In a trap door avulsion, she said, the distal matrix is primarily visualized, so this may be a good option for a longitudinal melanonychia arising from the distal matrix. A Freer elevator is used to detach the nail plate from the bed and the matrix, after which the nail plate can be lifted with a hemostat.

In a partial proximal avulsion, the proximal nail fold is reflected, so it’s a better option when the proximal nail matrix needs evaluation, she said.

After the avulsion has been done, “the matrix has been exposed. Now what? Punch or shave?” asked Dr. Skelsey. She noted that she used to perform punch biopsies on “everything,” and that it’s a good option if the pigmented area spans 3 mm or less. One issue, though, is that the specimen can get stuck in the puncher, and extraction can make it difficult to deliver an intact specimen.

Shave biopsies, Dr. Skelsey said, are effective in dealing with nail matrix lesions. They can yield an accurate pathologic diagnosis, and the biopsied digits healed without nail dystrophy in about three quarters of the cases in one study, she said. Potential recurrence of pigmentation is one drawback of the shave technique, she said.

With a shave biopsy, she performs tangential incisions of the proximal and lateral nail folds, and scores and reflects the nail. Then, the band of pigment is shaved tangentially. She cauterizes the area, and sometimes will use a bit of an absorbable gelatin sponge (Gelfoam) as well. Then the proximal nail fold and nail plate are sutured.

Replacing the nail plate results in better cosmesis and is much more comfortable for the patient, she said. An 18-gauge needle can be used to bore a hole through the avulsed nail plate, which may be held in an antiseptic solution soak during the biopsy. The sutures should then be placed from skin to nail plate, so nail fragments aren’t driven into the skin during the suturing process. Finally, specimen margins should be inked, and separate labeled formalin jars are needed for the nail plate, nail bed, and the matrix.

Dr. Skelsey reported that she had no conflicts of interest.

koakes@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @karioakes

CHICAGO – Maral Skelsey, MD, doesn’t get flowers from her patients very often. But, she said, a big bouquet recently landed on her desk after she had performed a nail biopsy on a patient. The note from the patient read, “That wasn’t as bad as I thought it would be!”

The patient’s relief after the procedure highlights the apprehension that both patients and dermatologists can feel when a nail biopsy becomes necessary, said Dr. Skelsey, director of dermatologic surgery at Georgetown University, Washington, D.C.

Speaking at the summer meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology, Dr. Skelsey said that the most important advice she can give about the nail biopsy is, “Do it early and often.”

Dr. Skelsey reminded the audience that the musician Bob Marley died of malignant melanoma; the first sign of his cancer was a longitudinal melanonychia that went unbiopsied. “The biggest mistake we make is not doing it,” she said.

In performing a nail biopsy, said Dr. Skelsey, the goals are, first and foremost, to optimize the pathologic diagnosis. Correct technique can help avoid complications such as bleeding, infection, and nail dystrophy; the right approach can minimize pain and anxiety, she added.

In preparing for a biopsy for melanonychia, “dermoscopy can be very helpful” in assessing the location of the pigment and fine-tuning planning for the biopsy, said Dr. Skelsey. Also, if the streak of melanonychia has reached the distal nail, sending the clipping for pathology can be useful as well.

For dorsal pigmentation, the proximal nail matrix should be biopsied.

“Do not use a punch biopsy on the nail fold to diagnose melanoma – you will get a false negative,” Dr. Skelsey said. It’s not possible to get an accurate diagnosis going through the nail plate to the nail bed, she said.

The preoperative assessment is usually straightforward. Pertinent items in the patient’s history include any medication allergies, current anticoagulation, and any history of prior trauma to the digit to be biopsied. Occasionally, imaging may be helpful, and patients should always be assessed for vascular insufficiency, she noted.

Preoperatively, she asks her patients to remove nail polish and pretreat the area with povidone iodine for 2 days prior to the procedure. Patients need to have a ride home after the procedure, and should be prepared to elevate the affected extremity for 48 hours post procedure. If a toenail is biopsied, they’re advised to come with a postop shoe.

Her patients receive a 5-minute isopropyl alcohol wash of the area to be biopsied just before the procedure, followed by air drying and a 5-minute scrub with 7.5% povidone iodine, which then is wiped off preprocedure.

For hemostasis, a tourniquet can be improvised with a sterile glove finger and a hemostat; there are also dedicated finger cots available that work well for this purpose, she said. In addition to nail nippers and a nail elevator, an English nail splitter can be helpful, said Dr. Skelsey.

For anesthesia, she said she ordinarily uses a 30 gauge needle with buffered lidocaine and epinephrine at room temperature to deliver a wing block. Beginning about 1 cm proximal and lateral to the junction of the proximal and lateral nail fold, the dermatologist can slowly inject about 1.5 cc per side. As the block takes effect, the lateral nail fold will blanch distally in a wing-shaped pattern. This technique, she said, also has the benefit of acting as a volumetric tourniquet.

“To avulse or not to avulse?” asked Dr. Skelsey. “I used to avulse almost everything,” she said, but noted that a complete avulsion is a “pretty traumatic” procedure. Now, unless a full avulsion is required for complete and accurate pathology, she will usually perform a partial nail plate avulsion.

A partial avulsion can reduce pain and morbidity, and can be done by two different methods: the partial proximal avulsion, and the “trap door” avulsion. In a trap door avulsion, she said, the distal matrix is primarily visualized, so this may be a good option for a longitudinal melanonychia arising from the distal matrix. A Freer elevator is used to detach the nail plate from the bed and the matrix, after which the nail plate can be lifted with a hemostat.

In a partial proximal avulsion, the proximal nail fold is reflected, so it’s a better option when the proximal nail matrix needs evaluation, she said.

After the avulsion has been done, “the matrix has been exposed. Now what? Punch or shave?” asked Dr. Skelsey. She noted that she used to perform punch biopsies on “everything,” and that it’s a good option if the pigmented area spans 3 mm or less. One issue, though, is that the specimen can get stuck in the puncher, and extraction can make it difficult to deliver an intact specimen.

Shave biopsies, Dr. Skelsey said, are effective in dealing with nail matrix lesions. They can yield an accurate pathologic diagnosis, and the biopsied digits healed without nail dystrophy in about three quarters of the cases in one study, she said. Potential recurrence of pigmentation is one drawback of the shave technique, she said.

With a shave biopsy, she performs tangential incisions of the proximal and lateral nail folds, and scores and reflects the nail. Then, the band of pigment is shaved tangentially. She cauterizes the area, and sometimes will use a bit of an absorbable gelatin sponge (Gelfoam) as well. Then the proximal nail fold and nail plate are sutured.

Replacing the nail plate results in better cosmesis and is much more comfortable for the patient, she said. An 18-gauge needle can be used to bore a hole through the avulsed nail plate, which may be held in an antiseptic solution soak during the biopsy. The sutures should then be placed from skin to nail plate, so nail fragments aren’t driven into the skin during the suturing process. Finally, specimen margins should be inked, and separate labeled formalin jars are needed for the nail plate, nail bed, and the matrix.

Dr. Skelsey reported that she had no conflicts of interest.

koakes@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @karioakes

AT THE 2017 AAD SUMMER MEETING

Lessons abound for dermatologists when animal health and human health intersect

NEW YORK – We share more than affection with our dogs and cats. We also share diseases – about which our four-legged furry friends can teach us plenty.

That was the conclusion of speakers at a session on “cases at the intersection of human and veterinary dermatology,” presented at the summer meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology.

“Human health is intimately connected to animal health,” said Jennifer Gardner, MD, of the division of dermatology, University of Washington, Seattle, and a collaborating member of the school’s Center for One Health Research. The One Health framework looks at factors involved in the human, environmental, and animal sectors from the molecular level to the individual level and even to the planetary level.

Dr. Gardner challenged her audience to think beyond their individual areas of expertise. “How does the work you’re doing with a patient or test tube connect up the line and make an impact to levels higher up?” she asked.

The One Health framework also challenges practitioners to look horizontally, at how work done in the human world connects to what’s going on in the veterinary world – that is, how treatments for dermatologic conditions in dogs may one day affect how dermatologists treat the same or similar disorders in humans.

Learning from the mighty mite

For example, the study of mites that live on the skin of animals could eventually shed light on how dermatologists treat mite-related conditions in humans.

Dirk M. Elston, MD, professor and chair of the department of dermatology at the Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, noted that Demodex mites occur in humans and in pets.

In such cases, “sulfur tends to be my most reliable” treatment, he said, noting that it releases a rotten egg smell. “You’re basically gassing the organism.” Dr. Elston said he frequently gets calls from fellow dermatologists whose antimite efforts have failed with ivermectin and permethrin and does not hesitate to give his advice. “I’m like a broken record,” he said. “Sulfur, sulfur, sulfur, sulfur.”

The Demodex mite affects dogs to varying degrees, depending on where they live, said Kathryn Rook, VMD, of the department of dermatology at the University of Pennsylvania School of Veterinary Medicine, Philadelphia. In North America, demodicosis occurs in 0.38%-0.58% of dogs, and in 25% of dogs in Mexico, she said.

Amitraz, the only Food and Drug Administration–approved treatment for canine demodicosis, is available only as a dip. But it has fallen from favor as a result of sometimes serious side effects, which can include sedation, bradycardia, ataxia, vomiting, diarrhea, and hyperglycemia.

Daily administration of oral ivermectin – often for months – also carries a risk of side effects, including dilated pupils, ataxia, sedation, stupor, coma, hypersalivation, vomiting, diarrhea, blindness, tremors, seizures, and respiratory depression.

But the discovery of isoxazoline has “revolutionized” the treatment of demodicosis and other parasitic infestations in dogs, Dr. Rook said, citing quicker resolution of disease and improved quality of life for both the patient and its owner.

Isoxazoline, which Dr. Rook said carries little risk for side effects, is licensed in the United States only as a flea and tick preventive.

Atopic dermatitis

Atopic dermatitis (AD) tends to be similar in people and dogs, according to Charles W. Bradley, DVM, of the University of Pennsylvania School of Veterinary Medicine, Philadelphia. About 10%-30% of children and up to 10% of adults have the disorder, the prevalence of which has more than doubled in recent years, he said.

In dogs, the prevalence is 10%-20%, making it “an extraordinarily common disorder,” he said. Lesions tend to be located on the feet, face, pinnae, ventrum, and axilla/inguinum. Additional sites vary by breed, with Dalmatians tending to get AD on the lips, French Bulldogs on the eyelids, German Shepherds on the elbows, Shar-Peis on the thorax, and Boxers on the ears.

In humans, Staphylococcus aureus is the chief microorganism of concern, said Elizabeth Grice, PhD, of the department of dermatology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, who copresented the topic with Dr. Bradley.

“My true love is anything to do with the skin microbiome,” she said. “The more severe the disease, the lower the skin microbiome diversity.”

Though most studies of AD use mice as animal models, dogs would be better, according to Dr. Grice and Dr. Bradley.

That’s because canine AD occurs spontaneously and exhibits immunologic and clinical features similar to those of human AD. They include prevalence, environmental triggers, immunologic profiles, genetic predispositions, lesion distribution, and frequent colonization by Staphylococcus species. In addition, dogs and their owners tend to share the same environment.

A rash of itches

Among dermatology patients – man or beast – itch can outweigh rash as a key focus of concern, according to Brian Kim, MD, of the division of dermatology at Washington University in St. Louis, and codirector for the University’s Center for the Study of Itch. “The problem is my patients don’t complain about their rash; they complain about their itch,” he said. “But we don’t understand the basic question of itch.” In fact, the FDA has not approved any drugs for the treatment of chronic itch, he said.

For dogs, advances have been made with Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors, which “may function as immunomodulators,” Dr. Kim said. And JAK-1 selective inhibition “may be more effective than broad JAK blockade for itch.”

‘The perfect culture plate’

Lessons can be learned from studying canine AD, which “is immunophysiologically homologous to human AD,” said Daniel O. Morris, DVM, MPH, professor of dermatology, at the University of Pennsylvania School of Veterinary Medicine, Philadelphia. “The main difference: My patients are covered in dense hair coats.” Because of that, systemic treatment is necessary, he said.

Canine AD primarily affects areas where hair is sparse or where the surface microclimate is moist, he said. A dog’s ear canal, which can be 10 times longer than a human’s, harbors plenty of moisture and heat, he said. “It’s the perfect culture plate.”

But, he added, the owners of his patients tend to resist using topical therapies “that could be potentially smeared on the babies and grandma’s diabetic foot ulcer.” So he has long relied on systemic treatments, initially steroids and cyclosporine. But they can have major side effects, and cyclosporine can take 60-90 days before it exerts maximum effect.

A faster-acting compound called oclacitinib has shown promise based on its high affinity for inhibiting JAK-1 enzyme-mediated activation of cytokine expression, including interleukin (IL)-31, he said. “Clinical trials demonstrate an antipruritic efficacy equivalent to both prednisolone and cyclosporine,” he noted. Contraindications include a history of neoplasia, the presence of severe infection, and age under 1 year.

Monoclonal antibody targets IL-31

The latest promising arrival is lokivetmab, a monoclonal antibody that targets canine IL-31, according to Dr. Morris. It acts rapidly (within 1 day for many dogs) and prevents binding of IL-31 to its neuronal receptor for at least a month, thereby interrupting neurotransmission of itch.

But side effects can be serious and common. Equal efficacy with a reduced side effect is the holy grail, he said.

Some doctors are not waiting. “People are throwing these two products at anything that itches,” he said. Unfortunately, they tend to “work miserably” for causes other than AD, he added.

Dr. Gardner, Dr. Elston, Dr. Rook, Dr. Bradley, and Dr. Morris reported no financial conflicts. Dr. Grice’s disclosures include having served as a speaker for GlaxoSmithKline and for L’Oreal France, and having received grants/research funding from Janssen Research & Development. Dr. Kim has served as a consultant to biotechnology and pharmaceutical companies.

NEW YORK – We share more than affection with our dogs and cats. We also share diseases – about which our four-legged furry friends can teach us plenty.

That was the conclusion of speakers at a session on “cases at the intersection of human and veterinary dermatology,” presented at the summer meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology.

“Human health is intimately connected to animal health,” said Jennifer Gardner, MD, of the division of dermatology, University of Washington, Seattle, and a collaborating member of the school’s Center for One Health Research. The One Health framework looks at factors involved in the human, environmental, and animal sectors from the molecular level to the individual level and even to the planetary level.

Dr. Gardner challenged her audience to think beyond their individual areas of expertise. “How does the work you’re doing with a patient or test tube connect up the line and make an impact to levels higher up?” she asked.

The One Health framework also challenges practitioners to look horizontally, at how work done in the human world connects to what’s going on in the veterinary world – that is, how treatments for dermatologic conditions in dogs may one day affect how dermatologists treat the same or similar disorders in humans.

Learning from the mighty mite

For example, the study of mites that live on the skin of animals could eventually shed light on how dermatologists treat mite-related conditions in humans.

Dirk M. Elston, MD, professor and chair of the department of dermatology at the Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, noted that Demodex mites occur in humans and in pets.

In such cases, “sulfur tends to be my most reliable” treatment, he said, noting that it releases a rotten egg smell. “You’re basically gassing the organism.” Dr. Elston said he frequently gets calls from fellow dermatologists whose antimite efforts have failed with ivermectin and permethrin and does not hesitate to give his advice. “I’m like a broken record,” he said. “Sulfur, sulfur, sulfur, sulfur.”

The Demodex mite affects dogs to varying degrees, depending on where they live, said Kathryn Rook, VMD, of the department of dermatology at the University of Pennsylvania School of Veterinary Medicine, Philadelphia. In North America, demodicosis occurs in 0.38%-0.58% of dogs, and in 25% of dogs in Mexico, she said.

Amitraz, the only Food and Drug Administration–approved treatment for canine demodicosis, is available only as a dip. But it has fallen from favor as a result of sometimes serious side effects, which can include sedation, bradycardia, ataxia, vomiting, diarrhea, and hyperglycemia.

Daily administration of oral ivermectin – often for months – also carries a risk of side effects, including dilated pupils, ataxia, sedation, stupor, coma, hypersalivation, vomiting, diarrhea, blindness, tremors, seizures, and respiratory depression.

But the discovery of isoxazoline has “revolutionized” the treatment of demodicosis and other parasitic infestations in dogs, Dr. Rook said, citing quicker resolution of disease and improved quality of life for both the patient and its owner.

Isoxazoline, which Dr. Rook said carries little risk for side effects, is licensed in the United States only as a flea and tick preventive.

Atopic dermatitis

Atopic dermatitis (AD) tends to be similar in people and dogs, according to Charles W. Bradley, DVM, of the University of Pennsylvania School of Veterinary Medicine, Philadelphia. About 10%-30% of children and up to 10% of adults have the disorder, the prevalence of which has more than doubled in recent years, he said.

In dogs, the prevalence is 10%-20%, making it “an extraordinarily common disorder,” he said. Lesions tend to be located on the feet, face, pinnae, ventrum, and axilla/inguinum. Additional sites vary by breed, with Dalmatians tending to get AD on the lips, French Bulldogs on the eyelids, German Shepherds on the elbows, Shar-Peis on the thorax, and Boxers on the ears.

In humans, Staphylococcus aureus is the chief microorganism of concern, said Elizabeth Grice, PhD, of the department of dermatology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, who copresented the topic with Dr. Bradley.

“My true love is anything to do with the skin microbiome,” she said. “The more severe the disease, the lower the skin microbiome diversity.”

Though most studies of AD use mice as animal models, dogs would be better, according to Dr. Grice and Dr. Bradley.

That’s because canine AD occurs spontaneously and exhibits immunologic and clinical features similar to those of human AD. They include prevalence, environmental triggers, immunologic profiles, genetic predispositions, lesion distribution, and frequent colonization by Staphylococcus species. In addition, dogs and their owners tend to share the same environment.

A rash of itches

Among dermatology patients – man or beast – itch can outweigh rash as a key focus of concern, according to Brian Kim, MD, of the division of dermatology at Washington University in St. Louis, and codirector for the University’s Center for the Study of Itch. “The problem is my patients don’t complain about their rash; they complain about their itch,” he said. “But we don’t understand the basic question of itch.” In fact, the FDA has not approved any drugs for the treatment of chronic itch, he said.

For dogs, advances have been made with Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors, which “may function as immunomodulators,” Dr. Kim said. And JAK-1 selective inhibition “may be more effective than broad JAK blockade for itch.”

‘The perfect culture plate’

Lessons can be learned from studying canine AD, which “is immunophysiologically homologous to human AD,” said Daniel O. Morris, DVM, MPH, professor of dermatology, at the University of Pennsylvania School of Veterinary Medicine, Philadelphia. “The main difference: My patients are covered in dense hair coats.” Because of that, systemic treatment is necessary, he said.

Canine AD primarily affects areas where hair is sparse or where the surface microclimate is moist, he said. A dog’s ear canal, which can be 10 times longer than a human’s, harbors plenty of moisture and heat, he said. “It’s the perfect culture plate.”

But, he added, the owners of his patients tend to resist using topical therapies “that could be potentially smeared on the babies and grandma’s diabetic foot ulcer.” So he has long relied on systemic treatments, initially steroids and cyclosporine. But they can have major side effects, and cyclosporine can take 60-90 days before it exerts maximum effect.

A faster-acting compound called oclacitinib has shown promise based on its high affinity for inhibiting JAK-1 enzyme-mediated activation of cytokine expression, including interleukin (IL)-31, he said. “Clinical trials demonstrate an antipruritic efficacy equivalent to both prednisolone and cyclosporine,” he noted. Contraindications include a history of neoplasia, the presence of severe infection, and age under 1 year.

Monoclonal antibody targets IL-31

The latest promising arrival is lokivetmab, a monoclonal antibody that targets canine IL-31, according to Dr. Morris. It acts rapidly (within 1 day for many dogs) and prevents binding of IL-31 to its neuronal receptor for at least a month, thereby interrupting neurotransmission of itch.

But side effects can be serious and common. Equal efficacy with a reduced side effect is the holy grail, he said.

Some doctors are not waiting. “People are throwing these two products at anything that itches,” he said. Unfortunately, they tend to “work miserably” for causes other than AD, he added.

Dr. Gardner, Dr. Elston, Dr. Rook, Dr. Bradley, and Dr. Morris reported no financial conflicts. Dr. Grice’s disclosures include having served as a speaker for GlaxoSmithKline and for L’Oreal France, and having received grants/research funding from Janssen Research & Development. Dr. Kim has served as a consultant to biotechnology and pharmaceutical companies.

NEW YORK – We share more than affection with our dogs and cats. We also share diseases – about which our four-legged furry friends can teach us plenty.

That was the conclusion of speakers at a session on “cases at the intersection of human and veterinary dermatology,” presented at the summer meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology.

“Human health is intimately connected to animal health,” said Jennifer Gardner, MD, of the division of dermatology, University of Washington, Seattle, and a collaborating member of the school’s Center for One Health Research. The One Health framework looks at factors involved in the human, environmental, and animal sectors from the molecular level to the individual level and even to the planetary level.

Dr. Gardner challenged her audience to think beyond their individual areas of expertise. “How does the work you’re doing with a patient or test tube connect up the line and make an impact to levels higher up?” she asked.

The One Health framework also challenges practitioners to look horizontally, at how work done in the human world connects to what’s going on in the veterinary world – that is, how treatments for dermatologic conditions in dogs may one day affect how dermatologists treat the same or similar disorders in humans.

Learning from the mighty mite

For example, the study of mites that live on the skin of animals could eventually shed light on how dermatologists treat mite-related conditions in humans.

Dirk M. Elston, MD, professor and chair of the department of dermatology at the Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, noted that Demodex mites occur in humans and in pets.

In such cases, “sulfur tends to be my most reliable” treatment, he said, noting that it releases a rotten egg smell. “You’re basically gassing the organism.” Dr. Elston said he frequently gets calls from fellow dermatologists whose antimite efforts have failed with ivermectin and permethrin and does not hesitate to give his advice. “I’m like a broken record,” he said. “Sulfur, sulfur, sulfur, sulfur.”

The Demodex mite affects dogs to varying degrees, depending on where they live, said Kathryn Rook, VMD, of the department of dermatology at the University of Pennsylvania School of Veterinary Medicine, Philadelphia. In North America, demodicosis occurs in 0.38%-0.58% of dogs, and in 25% of dogs in Mexico, she said.

Amitraz, the only Food and Drug Administration–approved treatment for canine demodicosis, is available only as a dip. But it has fallen from favor as a result of sometimes serious side effects, which can include sedation, bradycardia, ataxia, vomiting, diarrhea, and hyperglycemia.

Daily administration of oral ivermectin – often for months – also carries a risk of side effects, including dilated pupils, ataxia, sedation, stupor, coma, hypersalivation, vomiting, diarrhea, blindness, tremors, seizures, and respiratory depression.

But the discovery of isoxazoline has “revolutionized” the treatment of demodicosis and other parasitic infestations in dogs, Dr. Rook said, citing quicker resolution of disease and improved quality of life for both the patient and its owner.

Isoxazoline, which Dr. Rook said carries little risk for side effects, is licensed in the United States only as a flea and tick preventive.

Atopic dermatitis

Atopic dermatitis (AD) tends to be similar in people and dogs, according to Charles W. Bradley, DVM, of the University of Pennsylvania School of Veterinary Medicine, Philadelphia. About 10%-30% of children and up to 10% of adults have the disorder, the prevalence of which has more than doubled in recent years, he said.

In dogs, the prevalence is 10%-20%, making it “an extraordinarily common disorder,” he said. Lesions tend to be located on the feet, face, pinnae, ventrum, and axilla/inguinum. Additional sites vary by breed, with Dalmatians tending to get AD on the lips, French Bulldogs on the eyelids, German Shepherds on the elbows, Shar-Peis on the thorax, and Boxers on the ears.

In humans, Staphylococcus aureus is the chief microorganism of concern, said Elizabeth Grice, PhD, of the department of dermatology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, who copresented the topic with Dr. Bradley.

“My true love is anything to do with the skin microbiome,” she said. “The more severe the disease, the lower the skin microbiome diversity.”

Though most studies of AD use mice as animal models, dogs would be better, according to Dr. Grice and Dr. Bradley.

That’s because canine AD occurs spontaneously and exhibits immunologic and clinical features similar to those of human AD. They include prevalence, environmental triggers, immunologic profiles, genetic predispositions, lesion distribution, and frequent colonization by Staphylococcus species. In addition, dogs and their owners tend to share the same environment.

A rash of itches

Among dermatology patients – man or beast – itch can outweigh rash as a key focus of concern, according to Brian Kim, MD, of the division of dermatology at Washington University in St. Louis, and codirector for the University’s Center for the Study of Itch. “The problem is my patients don’t complain about their rash; they complain about their itch,” he said. “But we don’t understand the basic question of itch.” In fact, the FDA has not approved any drugs for the treatment of chronic itch, he said.

For dogs, advances have been made with Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors, which “may function as immunomodulators,” Dr. Kim said. And JAK-1 selective inhibition “may be more effective than broad JAK blockade for itch.”

‘The perfect culture plate’

Lessons can be learned from studying canine AD, which “is immunophysiologically homologous to human AD,” said Daniel O. Morris, DVM, MPH, professor of dermatology, at the University of Pennsylvania School of Veterinary Medicine, Philadelphia. “The main difference: My patients are covered in dense hair coats.” Because of that, systemic treatment is necessary, he said.

Canine AD primarily affects areas where hair is sparse or where the surface microclimate is moist, he said. A dog’s ear canal, which can be 10 times longer than a human’s, harbors plenty of moisture and heat, he said. “It’s the perfect culture plate.”

But, he added, the owners of his patients tend to resist using topical therapies “that could be potentially smeared on the babies and grandma’s diabetic foot ulcer.” So he has long relied on systemic treatments, initially steroids and cyclosporine. But they can have major side effects, and cyclosporine can take 60-90 days before it exerts maximum effect.

A faster-acting compound called oclacitinib has shown promise based on its high affinity for inhibiting JAK-1 enzyme-mediated activation of cytokine expression, including interleukin (IL)-31, he said. “Clinical trials demonstrate an antipruritic efficacy equivalent to both prednisolone and cyclosporine,” he noted. Contraindications include a history of neoplasia, the presence of severe infection, and age under 1 year.

Monoclonal antibody targets IL-31

The latest promising arrival is lokivetmab, a monoclonal antibody that targets canine IL-31, according to Dr. Morris. It acts rapidly (within 1 day for many dogs) and prevents binding of IL-31 to its neuronal receptor for at least a month, thereby interrupting neurotransmission of itch.

But side effects can be serious and common. Equal efficacy with a reduced side effect is the holy grail, he said.

Some doctors are not waiting. “People are throwing these two products at anything that itches,” he said. Unfortunately, they tend to “work miserably” for causes other than AD, he added.

Dr. Gardner, Dr. Elston, Dr. Rook, Dr. Bradley, and Dr. Morris reported no financial conflicts. Dr. Grice’s disclosures include having served as a speaker for GlaxoSmithKline and for L’Oreal France, and having received grants/research funding from Janssen Research & Development. Dr. Kim has served as a consultant to biotechnology and pharmaceutical companies.

AT THE 2017 AAD SUMMER MEETING

Questions plague platelet-rich plasma’s promise

NEW YORK – If platelet-rich plasma is good enough for Kim Kardashian, what more do you need to know?

Turns out, there’s plenty to know, and plenty more that remains unknown about the procedure, which is sometimes referred to as PRP or, in Kardashian’s case, as a “vampire facial,” according to Terrence Keaney, MD, of the department of dermatology, George Washington University, Washington.

It’s easy to make: draw blood, centrifuge it, and then deliver it. The platelets themselves are not the active substances. For that, you have to look at what the platelets release from their alpha granules. They include a wealth of growth factors, including platelet-derived growth factor, transforming growth factor, vascular endothelial growth factor, epidermal growth factor, fibroblast growth factor, and connective tissue growth factor.

That’s not all. “There are 800 other bioactive molecules secreted by platelets,” including cell adhesion molecules, cytokines, antimicrobial peptides, and anti-inflammatory molecules, said Dr. Keaney, founder and director of SkinDC, in Arlington, Va. “You bring it all together, what is PRP? A growth factor/cytokine cocktail.”

But, like the cocktails one can find in a college dorm, compared with the ones found at a bar at an upscale hotel, there can be big differences – depending on who’s doing the mixing.

Still, its reputation as an all-natural, safe product has made it appealing to the public, as well as to doctors in fields beyond dermatology, he said, citing sports medicine, dentistry, otolaryngology, ophthalmology, urology, wound healing, cosmetic medicine, and cardiothoracic and maxillofacial medicine.

The Food and Drug Administration considers it a blood product, which means that it is exempt from the FDA’s traditional regulatory pathways, which would require animal studies and clinical trials. Instead, oversight falls to the FDA’s Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research, which is responsible for regulating human cells, tissues, and cellular- and tissue-based products.

A number of device makers have used the 510(k) application to bring PRP preparation systems to market. Under the application, devices that are “substantially equivalent” to a currently marketed device gain FDA clearance (J Knee Surg. 2015 Feb;28[1]:29-34). The result is that many such systems are available.

Nearly all of the devices have received clearance to produce PRP for use with bone graft materials in platelet-rich products for use by orthopedic surgeons. Other uses of the product, like stimulating hair growth, would be considered off-label.

Nevertheless, the purveyors of PRP have found people willing to part with their money in exchange for the hope that they may be able to hold on to their hair. That is not surprising, given the “pretty meager” therapeutic armamentarium available to them, Dr. Keaney said, citing minoxidil and finasteride – each of which was approved more than 20 years ago.

He bemoaned the lack of standardization for everything from platelet preparation technique to potential applications, which include facial rejuvenation, wound healing, and hair loss. “PRP has hype and it has hope, but it needs help,” he said. “There are lots of clinical questions that need to be answered.”

He added that the data remain thin. “Unfortunately, our clinical data does not match the hype around PRP,” he said, citing a recently published meta-analysis of six studies involving 177 patients (J Cosmet Dermatol. 2017 Mar 13. doi: 10.1111/jocd.12331).

Its conclusion was measured: “Platelet-rich plasma injection for local hair restoration in patients with androgenetic alopecia seems to increase hair’s number and thickness with minimal or no collateral effects. However, the current evidence does not support this treatment’s modality over hair transplantation due to the lack of established protocols,” the authors wrote. The meta-analysis results, they added, “should be interpreted with caution because it consists of pooling many small studies and larger randomized studies should be performed to verify this perception.”

Questions include how to determine the proper concentration and how many times PRP should be centrifuged, Dr. Keaney said. And it is not clear how or how often to deliver PRP. Subdermally? Via microneedle? Both? After traumatizing the skin to increase endogenous activators? Daily? Weekly? Monthly?

“We don’t know,” he said.

And, Dr. Keaney acknowledged, that may not change. “There is little incentive for industry to do a large-scale study,” he said. “If the results aren’t what they look for then you’ve killed your golden goose.”

Still, he has not been dissuaded. “From my standpoint, there’s a good scientific rationale, a proposed mechanism of action, molecular pathways.”

Though the clinical data have been variable, the studies small, and the study designs inconsistent, “there is a trend towards clinical effect,” he said. “If this is done appropriately, using appropriate systems and protocols in your office, this can be a very safe procedure – with injection site discomfort,” he said.

Dr. Keaney has spoken on behalf of a PRP preparation manufacturer.

dermnews@frontlinemedcom.com

NEW YORK – If platelet-rich plasma is good enough for Kim Kardashian, what more do you need to know?

Turns out, there’s plenty to know, and plenty more that remains unknown about the procedure, which is sometimes referred to as PRP or, in Kardashian’s case, as a “vampire facial,” according to Terrence Keaney, MD, of the department of dermatology, George Washington University, Washington.

It’s easy to make: draw blood, centrifuge it, and then deliver it. The platelets themselves are not the active substances. For that, you have to look at what the platelets release from their alpha granules. They include a wealth of growth factors, including platelet-derived growth factor, transforming growth factor, vascular endothelial growth factor, epidermal growth factor, fibroblast growth factor, and connective tissue growth factor.

That’s not all. “There are 800 other bioactive molecules secreted by platelets,” including cell adhesion molecules, cytokines, antimicrobial peptides, and anti-inflammatory molecules, said Dr. Keaney, founder and director of SkinDC, in Arlington, Va. “You bring it all together, what is PRP? A growth factor/cytokine cocktail.”

But, like the cocktails one can find in a college dorm, compared with the ones found at a bar at an upscale hotel, there can be big differences – depending on who’s doing the mixing.

Still, its reputation as an all-natural, safe product has made it appealing to the public, as well as to doctors in fields beyond dermatology, he said, citing sports medicine, dentistry, otolaryngology, ophthalmology, urology, wound healing, cosmetic medicine, and cardiothoracic and maxillofacial medicine.

The Food and Drug Administration considers it a blood product, which means that it is exempt from the FDA’s traditional regulatory pathways, which would require animal studies and clinical trials. Instead, oversight falls to the FDA’s Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research, which is responsible for regulating human cells, tissues, and cellular- and tissue-based products.

A number of device makers have used the 510(k) application to bring PRP preparation systems to market. Under the application, devices that are “substantially equivalent” to a currently marketed device gain FDA clearance (J Knee Surg. 2015 Feb;28[1]:29-34). The result is that many such systems are available.

Nearly all of the devices have received clearance to produce PRP for use with bone graft materials in platelet-rich products for use by orthopedic surgeons. Other uses of the product, like stimulating hair growth, would be considered off-label.

Nevertheless, the purveyors of PRP have found people willing to part with their money in exchange for the hope that they may be able to hold on to their hair. That is not surprising, given the “pretty meager” therapeutic armamentarium available to them, Dr. Keaney said, citing minoxidil and finasteride – each of which was approved more than 20 years ago.

He bemoaned the lack of standardization for everything from platelet preparation technique to potential applications, which include facial rejuvenation, wound healing, and hair loss. “PRP has hype and it has hope, but it needs help,” he said. “There are lots of clinical questions that need to be answered.”

He added that the data remain thin. “Unfortunately, our clinical data does not match the hype around PRP,” he said, citing a recently published meta-analysis of six studies involving 177 patients (J Cosmet Dermatol. 2017 Mar 13. doi: 10.1111/jocd.12331).

Its conclusion was measured: “Platelet-rich plasma injection for local hair restoration in patients with androgenetic alopecia seems to increase hair’s number and thickness with minimal or no collateral effects. However, the current evidence does not support this treatment’s modality over hair transplantation due to the lack of established protocols,” the authors wrote. The meta-analysis results, they added, “should be interpreted with caution because it consists of pooling many small studies and larger randomized studies should be performed to verify this perception.”

Questions include how to determine the proper concentration and how many times PRP should be centrifuged, Dr. Keaney said. And it is not clear how or how often to deliver PRP. Subdermally? Via microneedle? Both? After traumatizing the skin to increase endogenous activators? Daily? Weekly? Monthly?

“We don’t know,” he said.

And, Dr. Keaney acknowledged, that may not change. “There is little incentive for industry to do a large-scale study,” he said. “If the results aren’t what they look for then you’ve killed your golden goose.”

Still, he has not been dissuaded. “From my standpoint, there’s a good scientific rationale, a proposed mechanism of action, molecular pathways.”

Though the clinical data have been variable, the studies small, and the study designs inconsistent, “there is a trend towards clinical effect,” he said. “If this is done appropriately, using appropriate systems and protocols in your office, this can be a very safe procedure – with injection site discomfort,” he said.

Dr. Keaney has spoken on behalf of a PRP preparation manufacturer.

dermnews@frontlinemedcom.com

NEW YORK – If platelet-rich plasma is good enough for Kim Kardashian, what more do you need to know?

Turns out, there’s plenty to know, and plenty more that remains unknown about the procedure, which is sometimes referred to as PRP or, in Kardashian’s case, as a “vampire facial,” according to Terrence Keaney, MD, of the department of dermatology, George Washington University, Washington.

It’s easy to make: draw blood, centrifuge it, and then deliver it. The platelets themselves are not the active substances. For that, you have to look at what the platelets release from their alpha granules. They include a wealth of growth factors, including platelet-derived growth factor, transforming growth factor, vascular endothelial growth factor, epidermal growth factor, fibroblast growth factor, and connective tissue growth factor.

That’s not all. “There are 800 other bioactive molecules secreted by platelets,” including cell adhesion molecules, cytokines, antimicrobial peptides, and anti-inflammatory molecules, said Dr. Keaney, founder and director of SkinDC, in Arlington, Va. “You bring it all together, what is PRP? A growth factor/cytokine cocktail.”

But, like the cocktails one can find in a college dorm, compared with the ones found at a bar at an upscale hotel, there can be big differences – depending on who’s doing the mixing.

Still, its reputation as an all-natural, safe product has made it appealing to the public, as well as to doctors in fields beyond dermatology, he said, citing sports medicine, dentistry, otolaryngology, ophthalmology, urology, wound healing, cosmetic medicine, and cardiothoracic and maxillofacial medicine.

The Food and Drug Administration considers it a blood product, which means that it is exempt from the FDA’s traditional regulatory pathways, which would require animal studies and clinical trials. Instead, oversight falls to the FDA’s Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research, which is responsible for regulating human cells, tissues, and cellular- and tissue-based products.

A number of device makers have used the 510(k) application to bring PRP preparation systems to market. Under the application, devices that are “substantially equivalent” to a currently marketed device gain FDA clearance (J Knee Surg. 2015 Feb;28[1]:29-34). The result is that many such systems are available.

Nearly all of the devices have received clearance to produce PRP for use with bone graft materials in platelet-rich products for use by orthopedic surgeons. Other uses of the product, like stimulating hair growth, would be considered off-label.

Nevertheless, the purveyors of PRP have found people willing to part with their money in exchange for the hope that they may be able to hold on to their hair. That is not surprising, given the “pretty meager” therapeutic armamentarium available to them, Dr. Keaney said, citing minoxidil and finasteride – each of which was approved more than 20 years ago.

He bemoaned the lack of standardization for everything from platelet preparation technique to potential applications, which include facial rejuvenation, wound healing, and hair loss. “PRP has hype and it has hope, but it needs help,” he said. “There are lots of clinical questions that need to be answered.”

He added that the data remain thin. “Unfortunately, our clinical data does not match the hype around PRP,” he said, citing a recently published meta-analysis of six studies involving 177 patients (J Cosmet Dermatol. 2017 Mar 13. doi: 10.1111/jocd.12331).

Its conclusion was measured: “Platelet-rich plasma injection for local hair restoration in patients with androgenetic alopecia seems to increase hair’s number and thickness with minimal or no collateral effects. However, the current evidence does not support this treatment’s modality over hair transplantation due to the lack of established protocols,” the authors wrote. The meta-analysis results, they added, “should be interpreted with caution because it consists of pooling many small studies and larger randomized studies should be performed to verify this perception.”

Questions include how to determine the proper concentration and how many times PRP should be centrifuged, Dr. Keaney said. And it is not clear how or how often to deliver PRP. Subdermally? Via microneedle? Both? After traumatizing the skin to increase endogenous activators? Daily? Weekly? Monthly?

“We don’t know,” he said.

And, Dr. Keaney acknowledged, that may not change. “There is little incentive for industry to do a large-scale study,” he said. “If the results aren’t what they look for then you’ve killed your golden goose.”

Still, he has not been dissuaded. “From my standpoint, there’s a good scientific rationale, a proposed mechanism of action, molecular pathways.”

Though the clinical data have been variable, the studies small, and the study designs inconsistent, “there is a trend towards clinical effect,” he said. “If this is done appropriately, using appropriate systems and protocols in your office, this can be a very safe procedure – with injection site discomfort,” he said.

Dr. Keaney has spoken on behalf of a PRP preparation manufacturer.

dermnews@frontlinemedcom.com

AT THE 2017 AAD SUMMER MEETING

Dermatologists have a role in managing GVHD

NEW YORK – Dermatologists have an important role to play in caring for patients with chronic graft versus host disease (GVHD), a condition whose cutaneous manifestations are many, stubborn, and often disabling.

Although a wide range of systemic therapies are available, topical and intralesional treatment with such agents as potent steroids and calcineurin inhibitors can also help with cutaneous manifestations of GVHD in some instances, said Kathryn Martires, MD, at the American Academy of Dermatology summer meeting. However, she noted, “there are no studies or series examining the use of topical steroids alone in these patients, partly speaking to the complexity of these patients and required other care, but partly also due to the lack of dermatologists’ involvement in the care of these patients on a wide scale.”

“The types of GVHD that are particularly amenable to high dose steroids are predominantly the epidermal types,” she said. These include ichthyotic and eczematous as well as lichen planus–like cutaneous GVHD. “We also use topical steroids frequently in the papulosquamous type, though this is a rare variant,” she added.

Topical steroids can be used for dermal skin changes of GVHD as well, including lichen sclerosus–like and focal morphea–like plaques, according to Dr. Martires of the department of dermatology at Stanford (Calif.) University. These lesions are often first seen in the skin folds of the neck.

Even for patients with more diffuse dermal sclerosis, topical steroids have a role in quieting specific areas where active flares are occurring, she noted. These flares can look like erythematous, scaly patches and are “particularly amenable” to spot treatment with topical steroids.

“Just like in vitiligo that’s not associated with GVHD, certainly, topical steroids have their role in treating vitiligo that’s associated with chronic GVHD,” Dr. Martires said. This scenario stands in contrast to the situation where a patient has postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, for example, further along in the course of epidermal GVHD. Steroids should be avoided in situations where there’s hyperpigmentation.

Topical steroids are not usually useful for chronic poikilodermatous GVHD, or, generally, when patients have little epidermal change and the GVHD-associated changes are mostly dermal or subcutaneous, she said.

“Intralesional steroids have their role” in GVHD, although this is another instance where there are no studies to back up their efficacy, and recommendations are based on consensus, Dr. Martires pointed out. Nodular sclerotic GVHD is a rare manifestation, with firm, keloid-like lesions. These can flatten with intralesional injections, said Dr. Martires.

Intralesional injections have also been described in the literature as a treatment for ulcerative oral GVHD, she noted. Other therapy options for oral mucosal GVHD are fluocinonide gel 0.05% or clobetasol gel 0.05%, with spot application to the lesions. When there’s more diffuse lichenoid GVHD of the mouth, dexamethasone or prednisolone oral rinses can also be used, but should be combined with nystatin to prevent thrush, she advised. Triamcinolone 0.1% can be used with topical benzocaine dental paste (Orabase).

Calcineurin inhibitors are another option for oral lesions. Patients generally have a good comfort level with starting topical calcineurin inhibitors, said Dr. Martires, because they’ve likely had exposure to the systemic formulation. Case series have reported improvement “primarily in lichenoid GVHD” with the adjunctive use of topical calcineurin inhibitors, she said. In the mouth, tacrolimus 0.1% can be put in dental paste for focal lesions, and cyclosporine and azathioprine oral solutions can also be used.

Dry mouth is common in GVHD. “Remember, in patients who have other skin symptoms like pruritus, to ask about oral sicca symptoms in order to avoid things that might exacerbate it, like antihistamines and [tricyclic antidepressants],” she added.

Genital mucosal GVHD can respond to topical steroids, with ointment as the preferred vehicle, said Dr. Martires, noting that clobetasol 0.05% ointment and fluocinolone 0.025% ointment are good options, and tacrolimus 0.1% ointment is a logical nonsteroidal topical choice for the genital mucosa.

“Intralesionals are also first-line therapy here,” and “may prevent progression and permanent scarring if initiated early,” she pointed out. However, these injections are quite painful, so “patients have to be quite motivated” to be on board with this line of therapy, she said, adding that numbing prior to injections can help with pain.

Genital discomfort in women may not all be GVHD-related. “Remember, in patients who have undergone several cycles of chemotherapy prior to transplant, that they often have been experiencing menopausal symptoms, sometimes for years, so estrogen cream can sometimes go a long way,” said Dr. Martires, adding, “Certainly, a reminder about lubrication during intercourse is appropriate.”

Also, she said, dermatologists can help patients understand how important it is to be vigilant in preserving skin integrity by, for example, keeping skin well moisturized, avoiding aggressive nail care, and wearing gloves for wet work.

Dr. Martires reported no relevant financial relationships.

koakes@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @karioakes

NEW YORK – Dermatologists have an important role to play in caring for patients with chronic graft versus host disease (GVHD), a condition whose cutaneous manifestations are many, stubborn, and often disabling.

Although a wide range of systemic therapies are available, topical and intralesional treatment with such agents as potent steroids and calcineurin inhibitors can also help with cutaneous manifestations of GVHD in some instances, said Kathryn Martires, MD, at the American Academy of Dermatology summer meeting. However, she noted, “there are no studies or series examining the use of topical steroids alone in these patients, partly speaking to the complexity of these patients and required other care, but partly also due to the lack of dermatologists’ involvement in the care of these patients on a wide scale.”

“The types of GVHD that are particularly amenable to high dose steroids are predominantly the epidermal types,” she said. These include ichthyotic and eczematous as well as lichen planus–like cutaneous GVHD. “We also use topical steroids frequently in the papulosquamous type, though this is a rare variant,” she added.

Topical steroids can be used for dermal skin changes of GVHD as well, including lichen sclerosus–like and focal morphea–like plaques, according to Dr. Martires of the department of dermatology at Stanford (Calif.) University. These lesions are often first seen in the skin folds of the neck.

Even for patients with more diffuse dermal sclerosis, topical steroids have a role in quieting specific areas where active flares are occurring, she noted. These flares can look like erythematous, scaly patches and are “particularly amenable” to spot treatment with topical steroids.

“Just like in vitiligo that’s not associated with GVHD, certainly, topical steroids have their role in treating vitiligo that’s associated with chronic GVHD,” Dr. Martires said. This scenario stands in contrast to the situation where a patient has postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, for example, further along in the course of epidermal GVHD. Steroids should be avoided in situations where there’s hyperpigmentation.

Topical steroids are not usually useful for chronic poikilodermatous GVHD, or, generally, when patients have little epidermal change and the GVHD-associated changes are mostly dermal or subcutaneous, she said.

“Intralesional steroids have their role” in GVHD, although this is another instance where there are no studies to back up their efficacy, and recommendations are based on consensus, Dr. Martires pointed out. Nodular sclerotic GVHD is a rare manifestation, with firm, keloid-like lesions. These can flatten with intralesional injections, said Dr. Martires.

Intralesional injections have also been described in the literature as a treatment for ulcerative oral GVHD, she noted. Other therapy options for oral mucosal GVHD are fluocinonide gel 0.05% or clobetasol gel 0.05%, with spot application to the lesions. When there’s more diffuse lichenoid GVHD of the mouth, dexamethasone or prednisolone oral rinses can also be used, but should be combined with nystatin to prevent thrush, she advised. Triamcinolone 0.1% can be used with topical benzocaine dental paste (Orabase).

Calcineurin inhibitors are another option for oral lesions. Patients generally have a good comfort level with starting topical calcineurin inhibitors, said Dr. Martires, because they’ve likely had exposure to the systemic formulation. Case series have reported improvement “primarily in lichenoid GVHD” with the adjunctive use of topical calcineurin inhibitors, she said. In the mouth, tacrolimus 0.1% can be put in dental paste for focal lesions, and cyclosporine and azathioprine oral solutions can also be used.

Dry mouth is common in GVHD. “Remember, in patients who have other skin symptoms like pruritus, to ask about oral sicca symptoms in order to avoid things that might exacerbate it, like antihistamines and [tricyclic antidepressants],” she added.

Genital mucosal GVHD can respond to topical steroids, with ointment as the preferred vehicle, said Dr. Martires, noting that clobetasol 0.05% ointment and fluocinolone 0.025% ointment are good options, and tacrolimus 0.1% ointment is a logical nonsteroidal topical choice for the genital mucosa.

“Intralesionals are also first-line therapy here,” and “may prevent progression and permanent scarring if initiated early,” she pointed out. However, these injections are quite painful, so “patients have to be quite motivated” to be on board with this line of therapy, she said, adding that numbing prior to injections can help with pain.

Genital discomfort in women may not all be GVHD-related. “Remember, in patients who have undergone several cycles of chemotherapy prior to transplant, that they often have been experiencing menopausal symptoms, sometimes for years, so estrogen cream can sometimes go a long way,” said Dr. Martires, adding, “Certainly, a reminder about lubrication during intercourse is appropriate.”

Also, she said, dermatologists can help patients understand how important it is to be vigilant in preserving skin integrity by, for example, keeping skin well moisturized, avoiding aggressive nail care, and wearing gloves for wet work.

Dr. Martires reported no relevant financial relationships.

koakes@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @karioakes

NEW YORK – Dermatologists have an important role to play in caring for patients with chronic graft versus host disease (GVHD), a condition whose cutaneous manifestations are many, stubborn, and often disabling.

Although a wide range of systemic therapies are available, topical and intralesional treatment with such agents as potent steroids and calcineurin inhibitors can also help with cutaneous manifestations of GVHD in some instances, said Kathryn Martires, MD, at the American Academy of Dermatology summer meeting. However, she noted, “there are no studies or series examining the use of topical steroids alone in these patients, partly speaking to the complexity of these patients and required other care, but partly also due to the lack of dermatologists’ involvement in the care of these patients on a wide scale.”

“The types of GVHD that are particularly amenable to high dose steroids are predominantly the epidermal types,” she said. These include ichthyotic and eczematous as well as lichen planus–like cutaneous GVHD. “We also use topical steroids frequently in the papulosquamous type, though this is a rare variant,” she added.

Topical steroids can be used for dermal skin changes of GVHD as well, including lichen sclerosus–like and focal morphea–like plaques, according to Dr. Martires of the department of dermatology at Stanford (Calif.) University. These lesions are often first seen in the skin folds of the neck.

Even for patients with more diffuse dermal sclerosis, topical steroids have a role in quieting specific areas where active flares are occurring, she noted. These flares can look like erythematous, scaly patches and are “particularly amenable” to spot treatment with topical steroids.

“Just like in vitiligo that’s not associated with GVHD, certainly, topical steroids have their role in treating vitiligo that’s associated with chronic GVHD,” Dr. Martires said. This scenario stands in contrast to the situation where a patient has postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, for example, further along in the course of epidermal GVHD. Steroids should be avoided in situations where there’s hyperpigmentation.

Topical steroids are not usually useful for chronic poikilodermatous GVHD, or, generally, when patients have little epidermal change and the GVHD-associated changes are mostly dermal or subcutaneous, she said.

“Intralesional steroids have their role” in GVHD, although this is another instance where there are no studies to back up their efficacy, and recommendations are based on consensus, Dr. Martires pointed out. Nodular sclerotic GVHD is a rare manifestation, with firm, keloid-like lesions. These can flatten with intralesional injections, said Dr. Martires.

Intralesional injections have also been described in the literature as a treatment for ulcerative oral GVHD, she noted. Other therapy options for oral mucosal GVHD are fluocinonide gel 0.05% or clobetasol gel 0.05%, with spot application to the lesions. When there’s more diffuse lichenoid GVHD of the mouth, dexamethasone or prednisolone oral rinses can also be used, but should be combined with nystatin to prevent thrush, she advised. Triamcinolone 0.1% can be used with topical benzocaine dental paste (Orabase).

Calcineurin inhibitors are another option for oral lesions. Patients generally have a good comfort level with starting topical calcineurin inhibitors, said Dr. Martires, because they’ve likely had exposure to the systemic formulation. Case series have reported improvement “primarily in lichenoid GVHD” with the adjunctive use of topical calcineurin inhibitors, she said. In the mouth, tacrolimus 0.1% can be put in dental paste for focal lesions, and cyclosporine and azathioprine oral solutions can also be used.

Dry mouth is common in GVHD. “Remember, in patients who have other skin symptoms like pruritus, to ask about oral sicca symptoms in order to avoid things that might exacerbate it, like antihistamines and [tricyclic antidepressants],” she added.

Genital mucosal GVHD can respond to topical steroids, with ointment as the preferred vehicle, said Dr. Martires, noting that clobetasol 0.05% ointment and fluocinolone 0.025% ointment are good options, and tacrolimus 0.1% ointment is a logical nonsteroidal topical choice for the genital mucosa.

“Intralesionals are also first-line therapy here,” and “may prevent progression and permanent scarring if initiated early,” she pointed out. However, these injections are quite painful, so “patients have to be quite motivated” to be on board with this line of therapy, she said, adding that numbing prior to injections can help with pain.

Genital discomfort in women may not all be GVHD-related. “Remember, in patients who have undergone several cycles of chemotherapy prior to transplant, that they often have been experiencing menopausal symptoms, sometimes for years, so estrogen cream can sometimes go a long way,” said Dr. Martires, adding, “Certainly, a reminder about lubrication during intercourse is appropriate.”

Also, she said, dermatologists can help patients understand how important it is to be vigilant in preserving skin integrity by, for example, keeping skin well moisturized, avoiding aggressive nail care, and wearing gloves for wet work.

Dr. Martires reported no relevant financial relationships.

koakes@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @karioakes

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE 2017 AAD SUMMER MEETING

The microbiota matters: In acne, it’s not us versus them

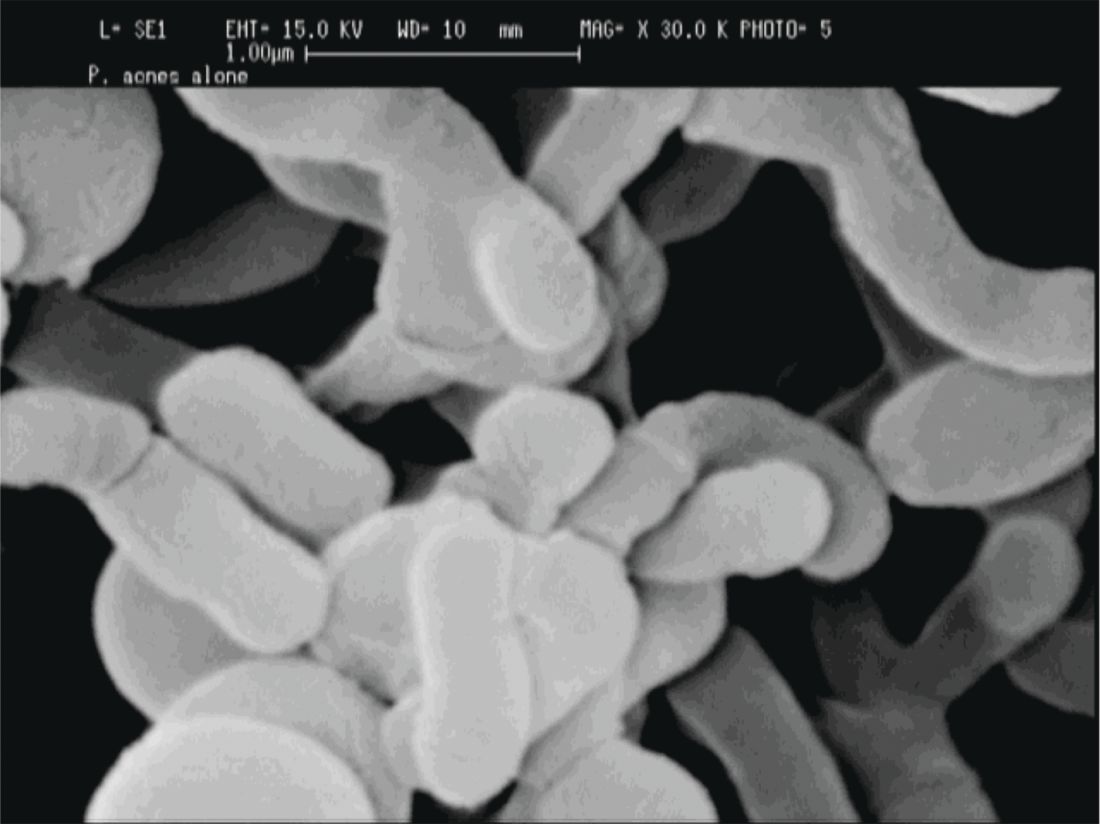

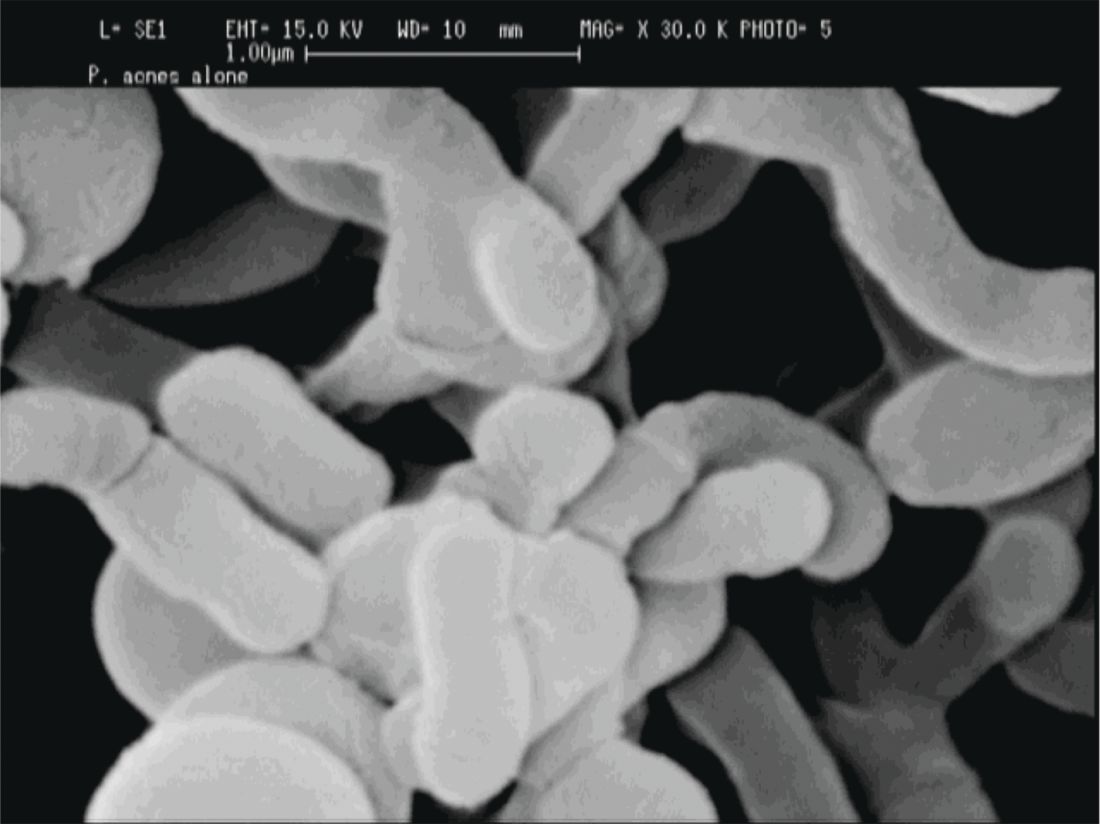

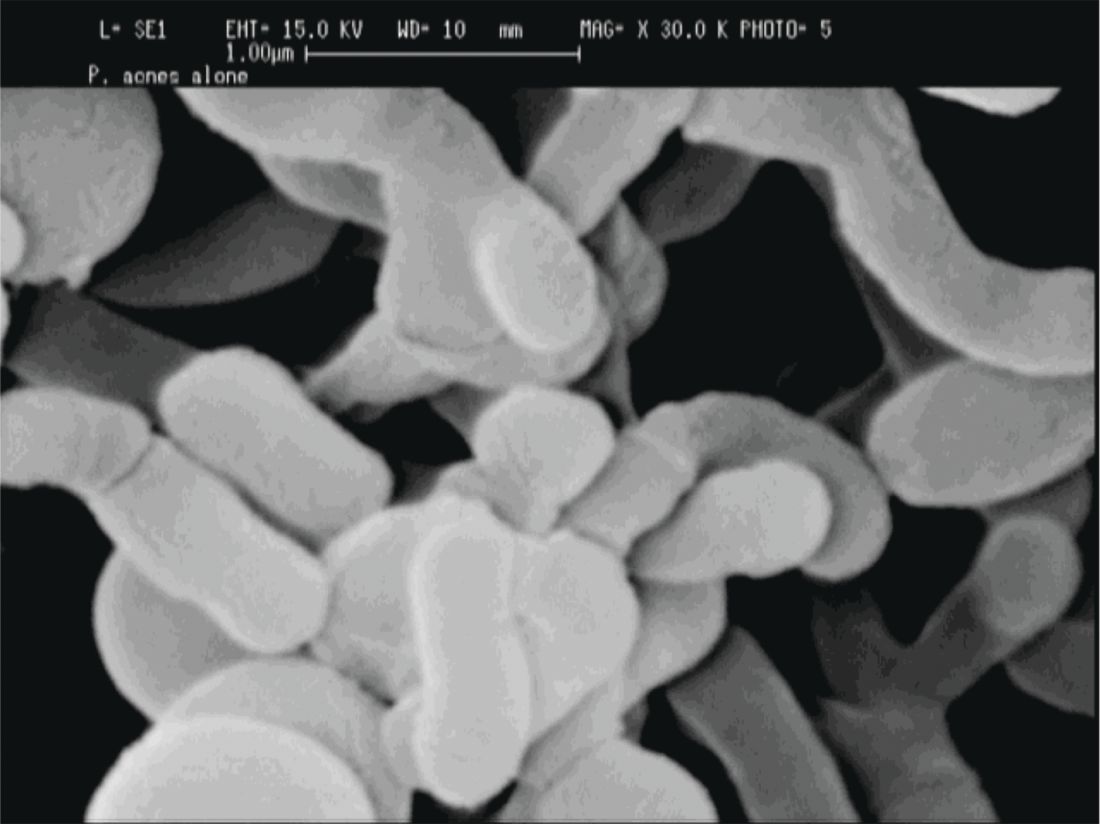

NEW YORK – Just as an imbalance in the intestinal microbiota can disrupt gut function, dysbiosis of the facial skin can allow acne-causing bacteria to flourish.

In acne, said Adam Friedman, MD, “we’ve always been talking about bacteria,” but now the thinking has shifted from just controlling Propionibacterium acnes to a subtler understanding of what’s happening on the skin of individuals with acne. Individuals may have their own unique skin microbiota – the community of organisms resident on the skin – but dysbiosis characterized by a lack of diversity is increasingly understood as a common theme in many skin disorders, and acne is no exception.

As in many other areas of medicine, dermatology’s understanding has been informed by genetic work that moves beyond the human genome. “Using newer technology, we were able to identify that our genome really was overshadowed by the microbial genome that makes up the populations in our skin, in our gut, and what have you,” said Dr. Friedman, speaking at the summer meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology.

The human body is like a planet to the bacteria that live on the human skin, and like a planet, the skin provides multiple “climates” for many bacterial ecosystems, said Dr. Friedman, director of translational research and dermatology residency program director, at George Washington University, Washington, DC.

Some areas are dry, some are moist; some are more oily, and some areas of the skin produce little sebum; while some are mostly dark and some are more likely to be exposed to light.

Considering skin from this perspective, it makes sense that bacterial microbiota for these disparate areas varies widely, with a different mix of bacteria found in the groin than on the forearm, he noted. Further, “each individual has his or her own microbiota fingerprint,” said Dr. Friedman, citing a 2012 study showing that in four healthy volunteers, the microbiota from swabs at four sites (antecubital fossa, back, nare, and plantar heel) varied widely both in diversity and composition (Genome Res. 2012 May;22[5]:850-9).

Multiple factors can contribute to this variability, which can include endogenous factors, such as host genotype, sex, age, immune system, and pathobiology. Exogenous factors, such as climate, geographic location, and occupational exposures, also play a part.

Increasingly, said Dr. Friedman, lack of bacterial diversity in skin microbiota is recognized as an important factor in many disease states, including atopic dermatitis and psoriasis. And bacterial diversity has recently been shown to be reduced on the facial skin of patients with acne, even on areas of clear skin.

When acne treatments work, a healthy facial microbiota is restored. And perhaps counterintuitively, patients with acne who receive isotretinoin and antibiotics have much greater diversity in the microbiota of their facial skin after treatment than before, according to a study recently published online (Exp Dermatol. 2017 Jun 21. doi: 10.1111/exd.13397).

For now, this is still a chicken-and-egg situation, Dr. Friedman said. “Does the disease cause the lack of diversity, or does the lack of diversity cause the disease to develop? We don’t know yet.” (Nat Rev Microbiol. 2011 Apr;9[4]:244-53).

“If we’re going to think about the surface of our skin as a barrier, we must consider the microbiota as part of that barrier.”

P. acnes “is a clear instigator in eliciting a host inflammatory response,” through its recognition by toll-like receptors and the inflammasome to induce inflammation, Dr. Friedman said. However, it can also help prevent the colonization of opportunistic pathogens, including methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus pyogenes by helping maintain an acidic skin pH. “When and how does a commensal [organism] become a pathogen?” he asked.