A 62-year-old man presented to the emergency department (ED) with a swollen, red, and painful right lower leg. He’d had bilateral lower leg swelling for 2 months, but the left leg became increasingly painful and red over the past 3 days. The patient also had a 3-day history of a diffuse rash that began on his right upper arm and spread to his left arm, both palms, both legs, and his back. It was mildly pruritic, but not painful.

The patient indicated that he had recently sought care from his primary care physician for lower respiratory symptoms. He had just completed a 5-day course of azithromycin and prednisone (50 mg/d for 5 days) the day before his ED visit.

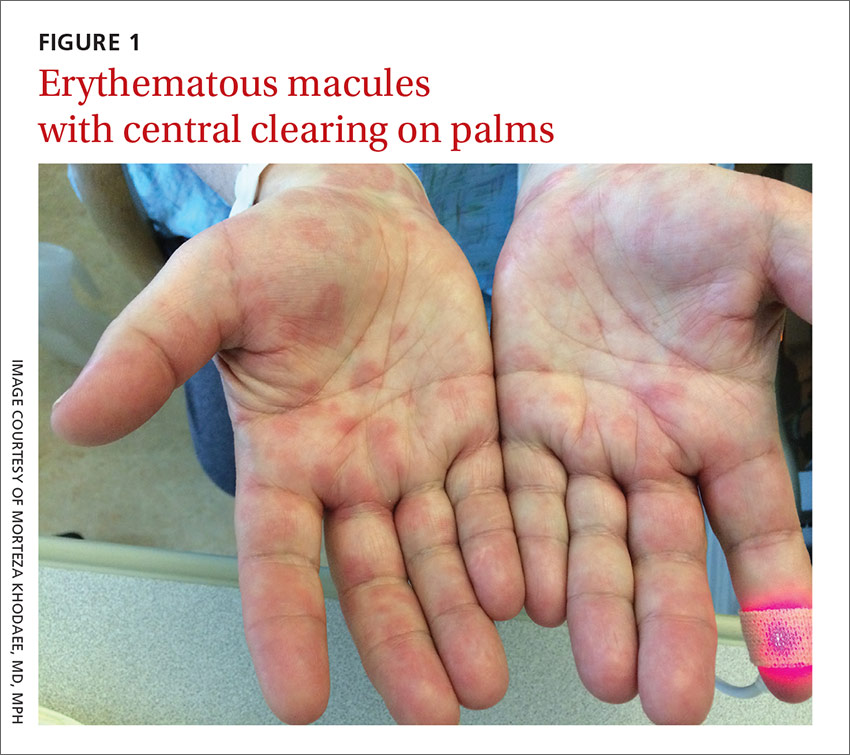

A lower extremity venous ultrasound revealed that the patient had a deep vein thrombosis (DVT). Computed tomography (CT) imaging of the chest with contrast revealed pulmonary emboli. He was treated with enoxaparin and warfarin. We diagnosed the rash based on the patient’s history and the appearance of the rash, which was comprised of blanching and erythematous macules with central clearing (FIGURE 1). (There were no blisters or mucosal involvement.)