User login

If you feel like the day doesn’t hold enough hours for you to get your work done, you’re right: (EHRs).

Investigators followed 141 academic PCPs between May 2019 and March 2023 and found they spent considerably more time engaging in EHR tasks during the final year of the study than in the prepandemic period. EHR time increased by over 8% on days with scheduled appointments and almost 20% on days without scheduled appointments.

“Physicians spend an unsustainable amount of time on EHR-based work, and that amount has increased steadily from 2019 to 2023,” Christine Sinsky, MD, vice president of professional satisfaction at the American Medical Association (AMA) and the senior author of the study, told this news organization. “It is imperative for healthcare systems to develop strategies to change the overall EHR workload trajectory to minimize PCPs’ occupational stress, including improved workflows, where the work is more appropriately distributed amongst the team.”

The study was published online on January 22, 2024, in the Annals of Family Medicine.

‘Pajama Time’

Dr. Sinsky said the motivation for conducting the current study was that PCPs have reported an increase in their workload, especially EHR tasks outside of work (“pajama time”) since the onset of the pandemic.

The research followed up on a 2017 analysis from the same group and other findings showing an increase in the time physicians spend in EHR tasks and the number of Inbox messages they receive from patients seeking medical advice increased during the months following the start of the pandemic.

“As a busy practicing PCP with a large panel of patients, my sense was that the workload was increasing even more, which is what our study confirmed,” said Brian G. Arndt, MD, of the Department of Family Medicine and Community Heath at the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, in Madison, Wisconsin, who led the new study.

The researchers analyzed EHR usage of 141 academic PCPs practicing family medicine, internal medicine, and general pediatrics, two thirds (66.7%) of whom were female. They compared the amount of time spent on EHR tasks during four timespans:

- May 2019 to February 2020

- June 2020 to March 2021

- May 2021 to March 2022

- April 2022 to March 2023

Each PCP’s time and Inbox message volume were calculated and then normalized over 8 hours of scheduled clinic appointments.

Increased Time, Increased Burnout

The study found evidence PCPs have reduced their clinical hours in response to their growing digital workload.

“We have a serious shortage of primary care physicians,” Dr. Sinsky said. “When PCPs cut back their clinical [work] as a coping mechanism for an unmanageable workload, this further exacerbates the primary care shortage, reducing access to care for patients.”

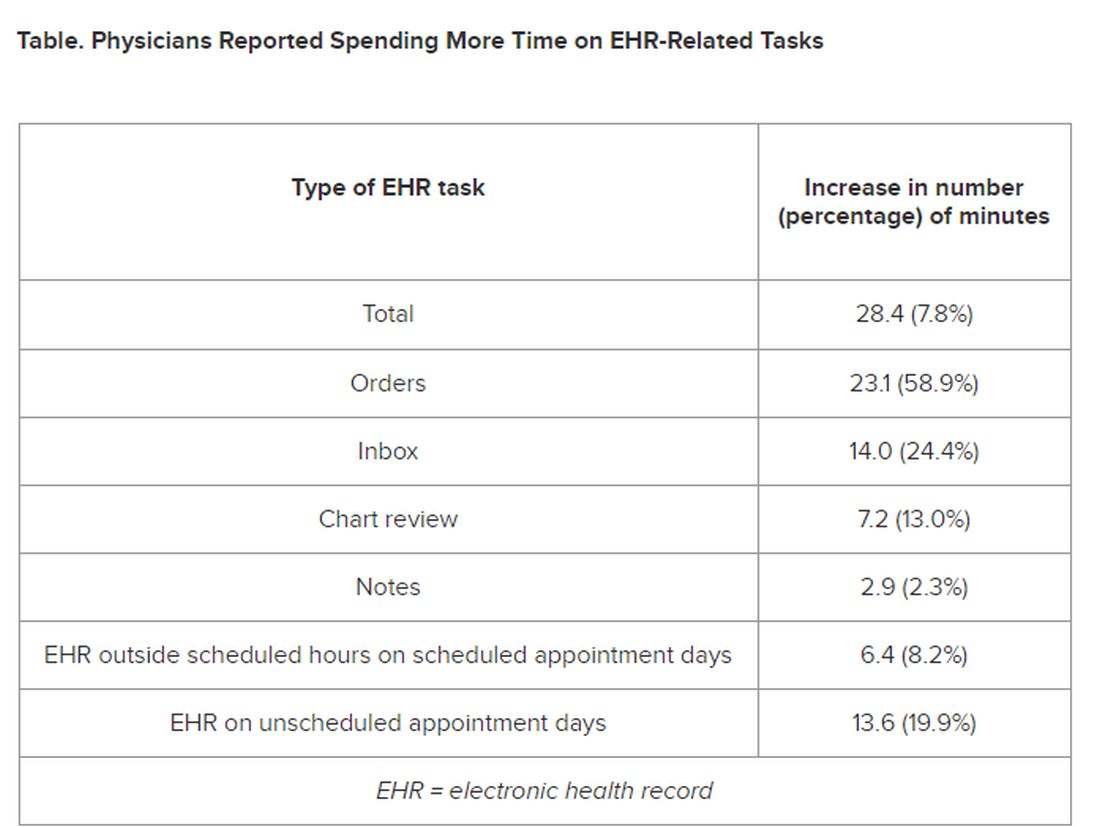

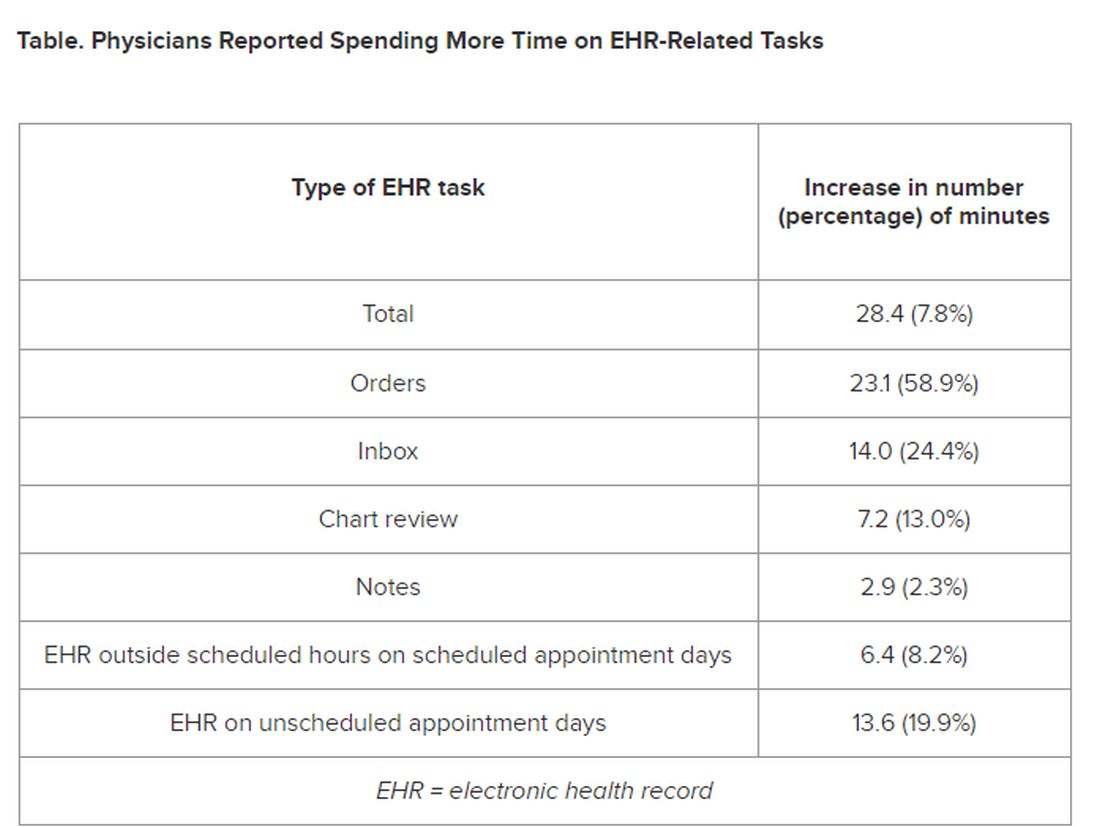

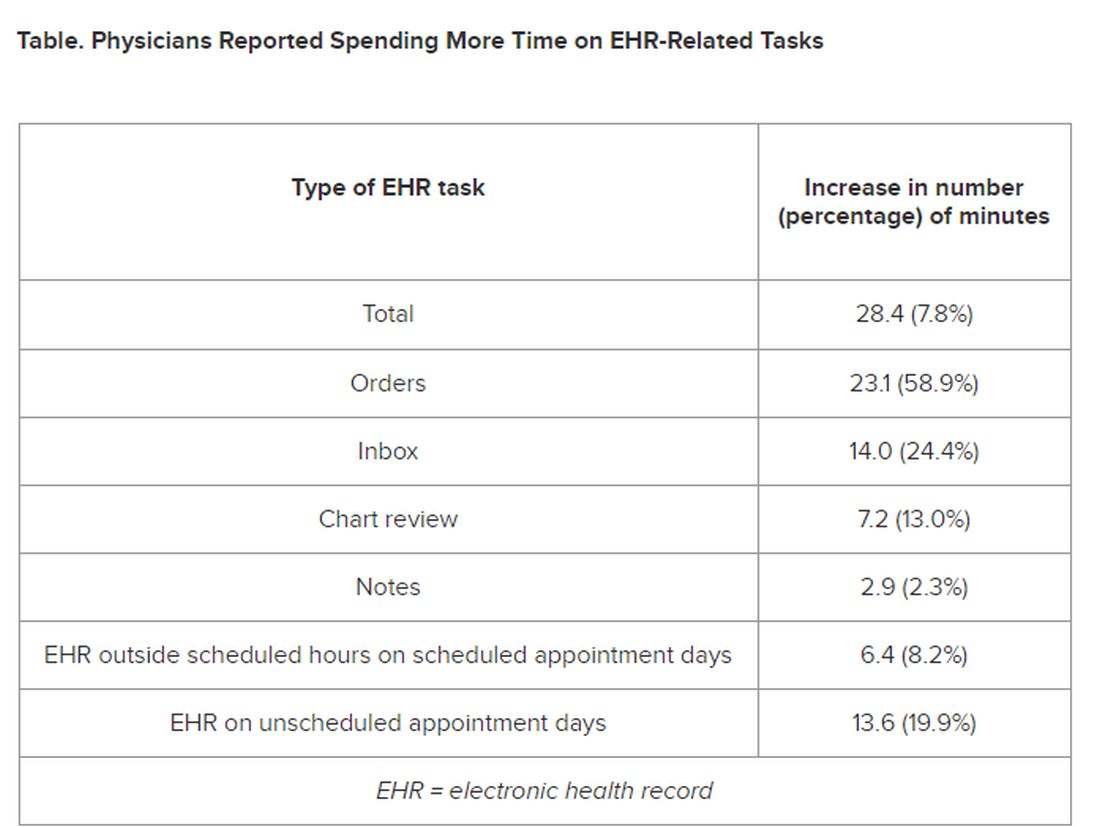

The researchers found increases from the first prepandemic period to the final period of their study in average time that PCPs spent at the EHR per 8 hours of scheduled clinic appointments (Table).

PCPs were inundated with several types of EHR-related responsibilities, including more medical advice requests (+55.5%) and more prescription messages (+19.5%) per 8 hours of scheduled clinic appointments. On the other hand, they had slightly fewer patient calls (−10.5%) and messages concerning test results (−2.7%).

A recent study of 307 PCPs across 31 primary care practices paralleled these findings. It found that physicians spent 36.2 minutes on the EHR per visit (interquartile range, 28.9-45.7 minutes). Included were 6.2 minutes of “pajama time” per visit and 7.8 minutes on the EHR per visit.

The amount of EHR time exceeded the amount of time allotted to a primary care visit (30 minutes). The authors commented that the EHR time burden “and the burnout associated with this burden represent a serious threat to the primary care physician workforce.”

“As more health systems across the country transition from fee-for-service to value-based payment arrangements, they need to balance the time PCPs and their care teams need for face-to-face care — in-person or video visits — with the increasing asynchronous care patients are seeking from us through the portal, for example, MyChart,” Dr. Arndt said.

Sinsky noted that when patients receive care from a PCP, quality is higher and costs are lower. “When access to primary care is further limited by virtue of physicians being overwhelmed by administrative work implemented via the EHR, so that they are reducing their hours, then we can expect negative consequences for patient care and costs of care.”

Tips for Reducing EHR Time

Arndt noted that some “brief investments” of time with patients “lead to high rates of return on decreased MyChart messaging.” For example, he has said to patients: “In the future, there’s no need to respond in MyChart with a ‘Thank you.’” Or “In the future, if you have questions from preappointment labs, no need to send me a separate message in MyChart prior to your visit since they’re typically just a few days out. I look closely at your labs and would always pick up the phone and call you if there was anything more urgent or pressing that needs more immediate action.”

Sinsky recommended two “high-yield opportunities” to reduce EHR-associated workload. The AMA offers a brief Inbox reduction checklist as well as a detailed toolkit to guide physicians and operational leaders in reducing the volume of unnecessary Inbox messages, she said.

Distribution of work among the team also can reduce the time physicians spent on order entry. “It doesn’t take a medical school education to enter orders for flu shots, lipid profiles, mammograms, and other tests, and yet we have primary care physicians around the country spending an hour or more per 8 hours of patient visits on this task,” she said.

‘Growing Mountain’

Sally Baxter, MD, assistant professor of ophthalmology and division chief for Ophthalmology Informatics and Data Sciences at University of California San Diego, said, “Studies like this ... are important for continuing to quantify the burden of EHR work and to evaluate potential interventions to reduce this burden and subsequent burnout.”

Baxter’s health system allows physicians to bill for asynchronous messaging when certain eligibility criteria are met. “This can deter frivolous messaging and also provide some compensation for the work involved,” she said.

“In addition, we’ve recently piloted using AI tools to help draft replies to patient messages in the EHR as another approach to tackling this important issue,” said Baxter, who wasn’t involved with the current study.

Eve Rittenberg, MD, an assistant professor at Harvard Medical School and a PCP at Brigham and Women’s Hospital Fish Center for Women’s Health, in Boston, recommended that healthcare systems “monitor EHR workload across gender, specialty, and other variables to develop equitable support and compensation models.”

Dr. Rittenberg, who wasn’t involved with the current study, said healthcare systems should consider supporting physicians by blocking out time during clinic sessions to manage their EHR work. “Cross-coverage systems are vital so that on their days off, physicians can unplug from the computer and know that their patients’ needs are being met,” she added.

This work was supported in part by the AMA Practice Transformation Initiative: EHR-Use Metrics Research which provided grant funding to several of the authors. Sinsky is employed by the AMA. Dr. Arndt and coauthors disclosed no relevant financial information. Dr. Baxter received nonfinancial support from Optonmed and Topcon for research studies and collaborated with some of the study authors on other research but not this particular study. Dr. Rittenberg received internal funding from the Brigham Care Redesign Incubator and Startup Program, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, for a previous pilot project of inbasket cross-coverage. She had no relevant current disclosures.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

If you feel like the day doesn’t hold enough hours for you to get your work done, you’re right: (EHRs).

Investigators followed 141 academic PCPs between May 2019 and March 2023 and found they spent considerably more time engaging in EHR tasks during the final year of the study than in the prepandemic period. EHR time increased by over 8% on days with scheduled appointments and almost 20% on days without scheduled appointments.

“Physicians spend an unsustainable amount of time on EHR-based work, and that amount has increased steadily from 2019 to 2023,” Christine Sinsky, MD, vice president of professional satisfaction at the American Medical Association (AMA) and the senior author of the study, told this news organization. “It is imperative for healthcare systems to develop strategies to change the overall EHR workload trajectory to minimize PCPs’ occupational stress, including improved workflows, where the work is more appropriately distributed amongst the team.”

The study was published online on January 22, 2024, in the Annals of Family Medicine.

‘Pajama Time’

Dr. Sinsky said the motivation for conducting the current study was that PCPs have reported an increase in their workload, especially EHR tasks outside of work (“pajama time”) since the onset of the pandemic.

The research followed up on a 2017 analysis from the same group and other findings showing an increase in the time physicians spend in EHR tasks and the number of Inbox messages they receive from patients seeking medical advice increased during the months following the start of the pandemic.

“As a busy practicing PCP with a large panel of patients, my sense was that the workload was increasing even more, which is what our study confirmed,” said Brian G. Arndt, MD, of the Department of Family Medicine and Community Heath at the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, in Madison, Wisconsin, who led the new study.

The researchers analyzed EHR usage of 141 academic PCPs practicing family medicine, internal medicine, and general pediatrics, two thirds (66.7%) of whom were female. They compared the amount of time spent on EHR tasks during four timespans:

- May 2019 to February 2020

- June 2020 to March 2021

- May 2021 to March 2022

- April 2022 to March 2023

Each PCP’s time and Inbox message volume were calculated and then normalized over 8 hours of scheduled clinic appointments.

Increased Time, Increased Burnout

The study found evidence PCPs have reduced their clinical hours in response to their growing digital workload.

“We have a serious shortage of primary care physicians,” Dr. Sinsky said. “When PCPs cut back their clinical [work] as a coping mechanism for an unmanageable workload, this further exacerbates the primary care shortage, reducing access to care for patients.”

The researchers found increases from the first prepandemic period to the final period of their study in average time that PCPs spent at the EHR per 8 hours of scheduled clinic appointments (Table).

PCPs were inundated with several types of EHR-related responsibilities, including more medical advice requests (+55.5%) and more prescription messages (+19.5%) per 8 hours of scheduled clinic appointments. On the other hand, they had slightly fewer patient calls (−10.5%) and messages concerning test results (−2.7%).

A recent study of 307 PCPs across 31 primary care practices paralleled these findings. It found that physicians spent 36.2 minutes on the EHR per visit (interquartile range, 28.9-45.7 minutes). Included were 6.2 minutes of “pajama time” per visit and 7.8 minutes on the EHR per visit.

The amount of EHR time exceeded the amount of time allotted to a primary care visit (30 minutes). The authors commented that the EHR time burden “and the burnout associated with this burden represent a serious threat to the primary care physician workforce.”

“As more health systems across the country transition from fee-for-service to value-based payment arrangements, they need to balance the time PCPs and their care teams need for face-to-face care — in-person or video visits — with the increasing asynchronous care patients are seeking from us through the portal, for example, MyChart,” Dr. Arndt said.

Sinsky noted that when patients receive care from a PCP, quality is higher and costs are lower. “When access to primary care is further limited by virtue of physicians being overwhelmed by administrative work implemented via the EHR, so that they are reducing their hours, then we can expect negative consequences for patient care and costs of care.”

Tips for Reducing EHR Time

Arndt noted that some “brief investments” of time with patients “lead to high rates of return on decreased MyChart messaging.” For example, he has said to patients: “In the future, there’s no need to respond in MyChart with a ‘Thank you.’” Or “In the future, if you have questions from preappointment labs, no need to send me a separate message in MyChart prior to your visit since they’re typically just a few days out. I look closely at your labs and would always pick up the phone and call you if there was anything more urgent or pressing that needs more immediate action.”

Sinsky recommended two “high-yield opportunities” to reduce EHR-associated workload. The AMA offers a brief Inbox reduction checklist as well as a detailed toolkit to guide physicians and operational leaders in reducing the volume of unnecessary Inbox messages, she said.

Distribution of work among the team also can reduce the time physicians spent on order entry. “It doesn’t take a medical school education to enter orders for flu shots, lipid profiles, mammograms, and other tests, and yet we have primary care physicians around the country spending an hour or more per 8 hours of patient visits on this task,” she said.

‘Growing Mountain’

Sally Baxter, MD, assistant professor of ophthalmology and division chief for Ophthalmology Informatics and Data Sciences at University of California San Diego, said, “Studies like this ... are important for continuing to quantify the burden of EHR work and to evaluate potential interventions to reduce this burden and subsequent burnout.”

Baxter’s health system allows physicians to bill for asynchronous messaging when certain eligibility criteria are met. “This can deter frivolous messaging and also provide some compensation for the work involved,” she said.

“In addition, we’ve recently piloted using AI tools to help draft replies to patient messages in the EHR as another approach to tackling this important issue,” said Baxter, who wasn’t involved with the current study.

Eve Rittenberg, MD, an assistant professor at Harvard Medical School and a PCP at Brigham and Women’s Hospital Fish Center for Women’s Health, in Boston, recommended that healthcare systems “monitor EHR workload across gender, specialty, and other variables to develop equitable support and compensation models.”

Dr. Rittenberg, who wasn’t involved with the current study, said healthcare systems should consider supporting physicians by blocking out time during clinic sessions to manage their EHR work. “Cross-coverage systems are vital so that on their days off, physicians can unplug from the computer and know that their patients’ needs are being met,” she added.

This work was supported in part by the AMA Practice Transformation Initiative: EHR-Use Metrics Research which provided grant funding to several of the authors. Sinsky is employed by the AMA. Dr. Arndt and coauthors disclosed no relevant financial information. Dr. Baxter received nonfinancial support from Optonmed and Topcon for research studies and collaborated with some of the study authors on other research but not this particular study. Dr. Rittenberg received internal funding from the Brigham Care Redesign Incubator and Startup Program, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, for a previous pilot project of inbasket cross-coverage. She had no relevant current disclosures.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

If you feel like the day doesn’t hold enough hours for you to get your work done, you’re right: (EHRs).

Investigators followed 141 academic PCPs between May 2019 and March 2023 and found they spent considerably more time engaging in EHR tasks during the final year of the study than in the prepandemic period. EHR time increased by over 8% on days with scheduled appointments and almost 20% on days without scheduled appointments.

“Physicians spend an unsustainable amount of time on EHR-based work, and that amount has increased steadily from 2019 to 2023,” Christine Sinsky, MD, vice president of professional satisfaction at the American Medical Association (AMA) and the senior author of the study, told this news organization. “It is imperative for healthcare systems to develop strategies to change the overall EHR workload trajectory to minimize PCPs’ occupational stress, including improved workflows, where the work is more appropriately distributed amongst the team.”

The study was published online on January 22, 2024, in the Annals of Family Medicine.

‘Pajama Time’

Dr. Sinsky said the motivation for conducting the current study was that PCPs have reported an increase in their workload, especially EHR tasks outside of work (“pajama time”) since the onset of the pandemic.

The research followed up on a 2017 analysis from the same group and other findings showing an increase in the time physicians spend in EHR tasks and the number of Inbox messages they receive from patients seeking medical advice increased during the months following the start of the pandemic.

“As a busy practicing PCP with a large panel of patients, my sense was that the workload was increasing even more, which is what our study confirmed,” said Brian G. Arndt, MD, of the Department of Family Medicine and Community Heath at the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, in Madison, Wisconsin, who led the new study.

The researchers analyzed EHR usage of 141 academic PCPs practicing family medicine, internal medicine, and general pediatrics, two thirds (66.7%) of whom were female. They compared the amount of time spent on EHR tasks during four timespans:

- May 2019 to February 2020

- June 2020 to March 2021

- May 2021 to March 2022

- April 2022 to March 2023

Each PCP’s time and Inbox message volume were calculated and then normalized over 8 hours of scheduled clinic appointments.

Increased Time, Increased Burnout

The study found evidence PCPs have reduced their clinical hours in response to their growing digital workload.

“We have a serious shortage of primary care physicians,” Dr. Sinsky said. “When PCPs cut back their clinical [work] as a coping mechanism for an unmanageable workload, this further exacerbates the primary care shortage, reducing access to care for patients.”

The researchers found increases from the first prepandemic period to the final period of their study in average time that PCPs spent at the EHR per 8 hours of scheduled clinic appointments (Table).

PCPs were inundated with several types of EHR-related responsibilities, including more medical advice requests (+55.5%) and more prescription messages (+19.5%) per 8 hours of scheduled clinic appointments. On the other hand, they had slightly fewer patient calls (−10.5%) and messages concerning test results (−2.7%).

A recent study of 307 PCPs across 31 primary care practices paralleled these findings. It found that physicians spent 36.2 minutes on the EHR per visit (interquartile range, 28.9-45.7 minutes). Included were 6.2 minutes of “pajama time” per visit and 7.8 minutes on the EHR per visit.

The amount of EHR time exceeded the amount of time allotted to a primary care visit (30 minutes). The authors commented that the EHR time burden “and the burnout associated with this burden represent a serious threat to the primary care physician workforce.”

“As more health systems across the country transition from fee-for-service to value-based payment arrangements, they need to balance the time PCPs and their care teams need for face-to-face care — in-person or video visits — with the increasing asynchronous care patients are seeking from us through the portal, for example, MyChart,” Dr. Arndt said.

Sinsky noted that when patients receive care from a PCP, quality is higher and costs are lower. “When access to primary care is further limited by virtue of physicians being overwhelmed by administrative work implemented via the EHR, so that they are reducing their hours, then we can expect negative consequences for patient care and costs of care.”

Tips for Reducing EHR Time

Arndt noted that some “brief investments” of time with patients “lead to high rates of return on decreased MyChart messaging.” For example, he has said to patients: “In the future, there’s no need to respond in MyChart with a ‘Thank you.’” Or “In the future, if you have questions from preappointment labs, no need to send me a separate message in MyChart prior to your visit since they’re typically just a few days out. I look closely at your labs and would always pick up the phone and call you if there was anything more urgent or pressing that needs more immediate action.”

Sinsky recommended two “high-yield opportunities” to reduce EHR-associated workload. The AMA offers a brief Inbox reduction checklist as well as a detailed toolkit to guide physicians and operational leaders in reducing the volume of unnecessary Inbox messages, she said.

Distribution of work among the team also can reduce the time physicians spent on order entry. “It doesn’t take a medical school education to enter orders for flu shots, lipid profiles, mammograms, and other tests, and yet we have primary care physicians around the country spending an hour or more per 8 hours of patient visits on this task,” she said.

‘Growing Mountain’

Sally Baxter, MD, assistant professor of ophthalmology and division chief for Ophthalmology Informatics and Data Sciences at University of California San Diego, said, “Studies like this ... are important for continuing to quantify the burden of EHR work and to evaluate potential interventions to reduce this burden and subsequent burnout.”

Baxter’s health system allows physicians to bill for asynchronous messaging when certain eligibility criteria are met. “This can deter frivolous messaging and also provide some compensation for the work involved,” she said.

“In addition, we’ve recently piloted using AI tools to help draft replies to patient messages in the EHR as another approach to tackling this important issue,” said Baxter, who wasn’t involved with the current study.

Eve Rittenberg, MD, an assistant professor at Harvard Medical School and a PCP at Brigham and Women’s Hospital Fish Center for Women’s Health, in Boston, recommended that healthcare systems “monitor EHR workload across gender, specialty, and other variables to develop equitable support and compensation models.”

Dr. Rittenberg, who wasn’t involved with the current study, said healthcare systems should consider supporting physicians by blocking out time during clinic sessions to manage their EHR work. “Cross-coverage systems are vital so that on their days off, physicians can unplug from the computer and know that their patients’ needs are being met,” she added.

This work was supported in part by the AMA Practice Transformation Initiative: EHR-Use Metrics Research which provided grant funding to several of the authors. Sinsky is employed by the AMA. Dr. Arndt and coauthors disclosed no relevant financial information. Dr. Baxter received nonfinancial support from Optonmed and Topcon for research studies and collaborated with some of the study authors on other research but not this particular study. Dr. Rittenberg received internal funding from the Brigham Care Redesign Incubator and Startup Program, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, for a previous pilot project of inbasket cross-coverage. She had no relevant current disclosures.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.