We know the potentially tragic outcome of postpartum hemorrhage (PPH): Worldwide, more than 140,000 women die every year as a result of PPH—one death every 4 minutes! Lest you dismiss PPH as a concern largely for developing countries, where it accounts for 25% of maternal deaths, consider this: In our highly developed nation, it accounts for nearly 8% of maternal deaths—a troubling statistic, to say the least.

The significant maternal death rate associated with PPH, and questions about how to reduce it, prompted the editors of OBG Management to talk with Haywood L. Brown, MD. Dr. Brown is Roy T. Parker Professor and chair of obstetrics and gynecology at Duke University Medical Center in Durham, NC. He is also a nationally recognized specialist in maternal-fetal medicine. In this interview, he discusses the full spectrum of management of PPH, from proactive assessment of a woman’s risk to determination of the cause to the tactic of last resort, emergent hysterectomy.

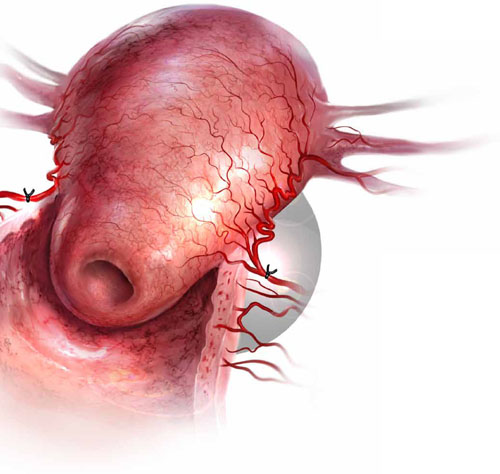

Uterine atony is the leading cause of postpartum hemorrhage. When medical management fails to stanch the bleeding, bilateral uterine artery ligation is one surgical option.

1. What is PPH?

OBG Management: Dr. Brown, let’s start with a simple but important aspect of PPH—how do you define it?

Dr. Brown: Obstetric hemorrhage is excessive bleeding that occurs during the intrapartum or postpartum period—specifically, estimated blood loss of 500 mL or more after vaginal delivery or 1,000 mL or more after cesarean delivery.

PPH is characterized as early or late, depending on whether the bleeding occurs within 24 hours of delivery (early, or primary) or between 24 hours and 6 to 12 weeks postpartum (late, or secondary). Primary PPH occurs in 4% to 6% of pregnancies.

Another way to define PPH: a decline of 10% or more in the baseline hematocrit level.

OBG Management: How do you measure blood loss?

Dr. Brown: The estimation of blood loss after delivery is an inexact science and typically yields an underestimation. Most clinicians rely on visual inspection to estimate the amount of blood collected in the drapes after vaginal delivery and in the suction bottles after cesarean delivery. Some facilities weigh lap pads or drapes to get a more accurate assessment of blood loss. In a routine delivery, no specific calorimetric measuring devices are used to estimate blood loss.

At my institution, we make an attempt to estimate blood loss at every delivery—vaginal or cesarean—and record the estimate. By doing this routinely, the clinician improves in accuracy and becomes more adept at identifying excessive bleeding.

OBG Management: Is blood loss the only variable that arouses concern about possible hemorrhage?

Dr. Brown: Because pregnant women experience an increase in blood volume and physiologic cardiovascular changes, the usual sign of significant bleeding can sometimes be masked. Therefore, any changes in maternal vital signs, such as a drop in blood pressure, tachycardia, or sensorial changes, may suggest that more blood has been lost than has been estimated.

Hypotension, dizziness, tachycardia or palpitations, and decreasing urine output will typically occur when more than 10% of maternal blood volume has been lost. In this situation, the patient should be given additional fluids, and a second intravenous line should be started using large-bore, 14-gauge access. In addition, the patient’s hemoglobin and hematocrit levels should be measured. All these actions constitute a first-line strategy to prevent shock and potential irreversible renal failure and cardiovascular collapse.

Low: 500 to 1,000 mL

This level of hemorrhage should be anticipated and can usually be managed with uterine massage and administration of a uterotonic agent, such as oxytocin. Intravenous fluids and careful monitoring of maternal vital signs are also warranted.

Active management of the third stage of labor has been shown to reduce the risk of significant postpartum hemorrhage (PPH). Active management includes:

- administration of a uterotonic agent immediately after delivery of the infant

- early cord clamping and cutting

- gentle cord traction with uterine counter-traction when the uterus is well contracted

- uterine massage.2

If these methods are unsuccessful in correcting the atony, uterotonics such as a prostaglandin (rectally administered misoprostol [800 mg] or intramuscular carboprost tromethamine [Hemabate; 250 μg/mL]) will usually succeed.

Medium: 1,000 to 1,500 mL

Blood loss of this volume is usually accompanied by cardiovascular signs, such as a fall in blood pressure, diaphoresis, and tachycardia. Women with this level of hemorrhage exhibit mild signs of shock.

It is important to correct maternal hypotension with fluids, restabilize vital signs, and resolve the bleeding expeditiously. If uterotonics and massage fail to stanch the bleeding, consider placing a balloon (e.g., Bakri balloon). Once the balloon is placed and inflated, it can be left for as long as 24 hours or until the uterus regains its tone.

Be sure to check hemoglobin and hematocrit levels and transfuse the patient, if necessary, especially if vital signs have not stabilized.

High: 1,500 to 2,000 mL, or greater

This is a medical emergency that must be managed aggressively to prevent morbidity and death. Blood loss of this volume will usually bring significant cardiovascular changes, such as hypotension, tachycardia, restlessness, pallor, oliguria, and cardiovascular collapse from hemorrhagic shock. this degree of blood loss means that the patient has lost 25% to 35% of her blood volume and will need blood-product replacement to prevent coagulation and the cascade of hemorrhage.

If conservative measures are unsuccessful, timely surgical intervention with B-Lynch suture, uterine vessel ligation, or hysterectomy is lifesaving.—HAYWOOD L. BROWN, MD