User login

Primary apocrine adenocarcinoma (AA) is a rare cutaneous malignancy, with most of the available information about this disease consolidated from anecdotal evidence of single case reports and small case series with fewer than 30 patients.1-11 Although certain histologic and immunohistochemical features have been suggested to be useful in the diagnosis of AA, there is no clear consensus on the required pathologic criteria.1,5,6,9,10,12,13 Additionally, the clinical presentation of AA is highly variable, which further adds to the challenge of making an accurate diagnosis.1-3,5,9,10,13

Apocrine adenocarcinoma usually arises in areas of high apocrine gland density such as the axillae or anogenital region.2,4,6 It also has been reported in areas such as the scalp, ear canal, eyelids, chest, nipples, arms, wrists, and fingers.4,8,10,14-16 Apocrine adenocarcinoma in unusual locations such as the eyelid and ear canal is thought to arise from modified apocrine glands such as the Moll glands of the eyelid and the ceruminous glands of the ear canal.9,10 The presence of ectopic apocrine glands may lead to AA in atypical sites such as the wrists and fingers.5,16 The areola is an apocrine-dense area; therefore, AA may present on the nipples or within supernumerary nipples anywhere along the milk lines.4

Apocrine adenocarcinoma clinically presents as an asymptomatic to slightly painful, slowly growing, and erythematous to violaceous nodule or tumor.4,6,9 However, in a minority of cases the initial presentation consists of a cystic or ulcerated mass with overlying granulation tissue and purulent discharge.6,9,11 A wide time frame from the onset of symptoms to diagnosis has been reported, ranging from weeks to decades.4,6-8 The conventional treatment of AA is wide local excision.2,4,6,9 Although AA often presents with local lymph node metastasis at the time of diagnosis, there is no consensus on the use of sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB), nodal dissection, or adjuvant chemoradiation therapy.1,3,8,9

We report the case of a 49-year-old man with primary AA of the left axilla; the clinical and histologic features of AA as well as the appropriate diagnostic and treatment modalities also are provided.

Case Report

A 49-year-old man with a slowly growing tender mass of the left axilla of 1 year’s duration was referred to our dermatology clinic for evaluation. A review of systems revealed loss of appetite, fatigue, and a 4-month history of unintentional weight loss (15–20 lb). The patient had a history of hepatitis C virus, intravenous drug use, alcohol abuse, and cigarette smoking (1 pack daily) for many years. Additionally, the patient reported a paternal family history of numerous visceral malignancies. Examination of the left axilla revealed a 1.5×5-cm ulcerated tumor that produced serosanguineous discharge and was tender to palpation (Figure 1). Two 1-cm, firm, freely mobile subcutaneous nodules with no overlying skin changes were palpable at the medial border of the ulcerated nodule. There was no additional cervical or axillary lymphadenopathy, and a breast examination was normal.

The differential diagnosis included primary squamous cell carcinoma or adnexal neoplasm, primary breast carcinoma, lymphoma, scrofuloderma, atypical mycobacterial infection, and cutaneous metastasis from an internal malignancy. Two 4-mm punch biopsies were performed and sent for routine histopathology and bacterial, fungal, and mycobacterial tissue cultures. To exclude a primary visceral malignancy or metastasis, computed tomography of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis; positron emission tomography (PET) from the base of the skull to the thighs; colonoscopy; magnetic resonance imaging of the brain; esophagogastroduodenoscopy; and mammography were conducted. Prominent left axillary lymphadenopathy was noted on computed tomography. Additionally, PET identified extranodal spread in the left axilla, left lateral chest wall, and the left sternocleidomastoid region. Furthermore, a 1-cm hypermetabolic nodule involving the right rectus abdominus muscle was noted on the PET scan. Based on their appearance, the nodules most likely represented metastasis from a primary skin malignancy. The rest of the studies were unremarkable. Serum tumor markers including prostate-specific antigen, cancer antigen 19-9, and carcinoembryonic antigen were within reference range. Immunostaining for estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, and ERBB2 (formerly HER2/neu) was negative. The only abnormalities noted on serum chemistries were slight elevations in aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase, alkaline phosphatase, and the a-fetoprotein tumor marker, which was attributed to chronic hepatitis C infection. Bacterial, fungal, and mycobacterial tissue cultures also were negative. These results ruled out infection and suggested against a primary visceral malignancy with cutaneous metastasis.

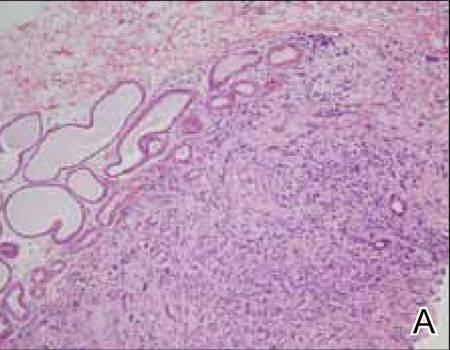

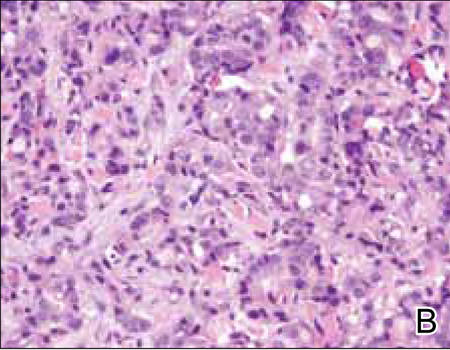

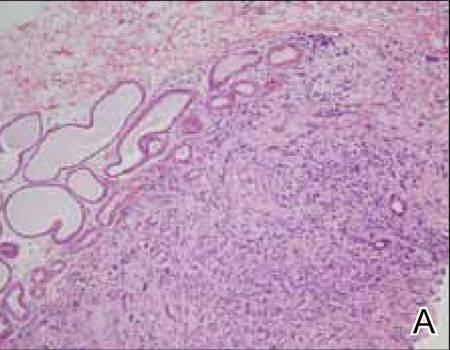

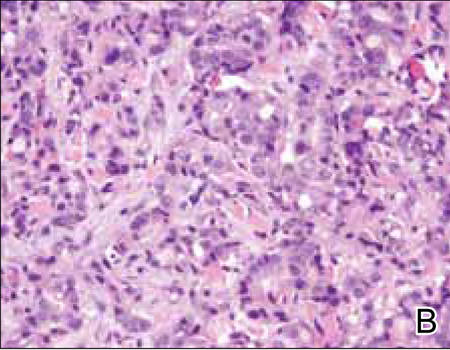

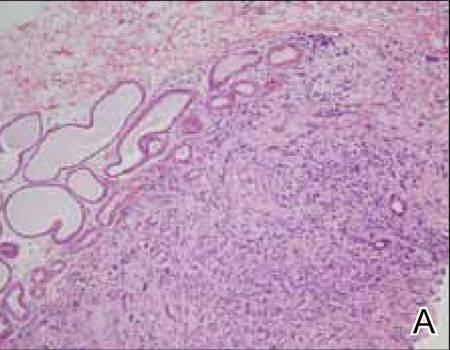

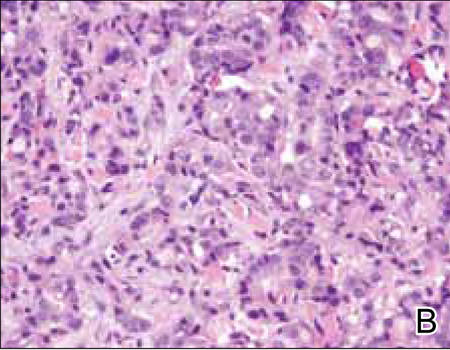

Histopathology revealed a moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma adjacent to healthy-appearing apocrine glands (Figure 2A). The normal glands were composed of cuboidal cells with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm and prominent nuclei. The cells were arranged in a single layer in a glandular formation with prominent decapitation secretion. Adjacent to the normal apocrine glandular tissue was a focus of malignant epithelioid cells that extended to the lateral and inferior margins. The neoplastic cells were cuboidal to angulated in appearance with prominent nuclei and seemed to form ill-defined tubular or glandular structures that partially resembled apocrine glands (Figure 2B). Decapitation secretion is a feature of apocrine differentiation. Examination of additional tissue sections of the tumor did not reveal remarkable decapitation secretion in contrast to the adjacent healthy apocrine glands. Rather, a solid sheet arrangement was primarily noted in several sections (Figure 2B). Neither frequent mitoses nor prominent cellular atypia were seen, and there was no evidence of lymphatic, perineural, or vascular invasion.

|

Immunohistochemically, tumor cells reacted strongly to cytokeratin AE1/AE3 and CAM5.2, stains used to identify various cytokeratins present in epithelial tissue. Staining for epithelial membrane antigen and carcinoembryonic antigen revealed focal glandular differentiation, which further supported the epithelial origin of the neoplastic cells. Gross cystic disease fluid protein 15 (GCDFP-15) is a marker of apocrine differentiation and may indicate a carcinoma of apocrine or eccrine origin. In our case, staining for GCDFP-15 was negative in the cutaneous sections but highlighted tumor cells in 6 of 13 ipsilateral lymph nodes from locoregional metastasis. The cellular and structural morphology, immunohistochemistry, and absence of an alternative primary visceral malignancy supported the diagnosis of primary AA.

Initially the patient was not considered to be a candidate for surgery due to the rapid growth of the tumor with metastases, fatigue, weight loss, and pain. Therefore, radiation therapy was started. The patient responded well to treatment with controlled pain and resolution of the palpable mass of the left axilla. Moreover, a follow-up PET scan revealed no residual tumor and persistent, albeit decreased, axillary lymphadenopathy. As the patient’s clinical status had improved, excision of the left axillary tumor with lymph node dissection was performed 10 months after initial presentation.

In this case, the differential diagnosis consisted of various cutaneous neoplasms, primary mammary carcinoma, cutaneous metastasis, and infection. Diagnostic imaging and laboratory testing failed to identify any primary internal malignancies. Similarly, the negative cultures ruled out an infectious process. Furthermore, the axillary mass was noted to be separate from the breast tissue on physical examination and mammography. Histologically, the tumor showed features that were suggestive of an anaplastic process as well as decapitation secretion and glandular formation that clearly resembled apocrine differentiation.

Comment

Apocrine adenocarcinoma arises from apocrine sweat glands and therefore is mostly reported in areas of high apocrine gland density such as the axillae and the anogenital region.2,4,6 However, AA also has been reported in unusual locations,1,5,10,14-16 and they may arise from a pre-existing nevus sebaceous or from supernumerary nipples, which can occur anywhere along the milk lines.4,15 Apocrine adenocarcinoma most commonly arises in individuals aged 40 to 50 years.3,17 A slight male predominance has been reported but no racial predilection.1,4-6 Although a few reports have described the development of AAs within pre-existing benign tumors such as apocrine adenomas, apocrine hyperplasias, cylindromas, and nevi sebaceous, they usually are thought to arise de novo.4-6

Clinical Presentation

Apocrine adenocarcinoma is highly variable in its clinical manifestation.1,6 Most cases arise as erythematous to violaceous, firm, solitary nodules. Nonetheless, AA also can present as erythematous patches of skin resembling erysipelas and ulcerated nodules with overlying granulation tissue and purulent exudate.4,6,9,11 Although AA typically is slow growing and indolent, the time frame reported from onset to diagnosis ranges from weeks to decades.1,6,7 Most cases present asymptomatically; when symptoms do occur, the most common ones are tenderness, purulent discharge, and restricted range of motion from extremely large tumors.3,9 Incidence of lymph node metastasis is reported at 40% to 50% at the time of presentation.4,6 Additionally, AA has a high rate of local recurrence, but extranodal metastasis rarely is seen.2,6 When metastasis does occur, it is via lymphatic and hematogenous spread.6,9 Metastatic dissemination of AA may occur in the liver, lungs, bone, brain, and parotid glands, as well as the skin via intraepidermal pagetoid spread.4,6,9,13

Histopathology

The histologic characteristics essential to the diagnosis of primary AA are anaplastic differentiation and apocrine origin.1,2,9,10,17 Apocrine units include coiled secretory glands that reside in the deep dermis connecting to a straight duct that empties into the isthmus of the hair follicle.9,13 These secretory glands have a single row of cuboidal secretory cells lining the tubular component and stratified squamous epithelium lining the straight intradermal component that opens onto the hair follicle.9 Contractile myoepithelial cells surround the secretory cell layer of the gland.9,13

The cuboidal secretory cells of the apocrine gland have abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm1,4,9 and are further characterized by glandular arrangement and decapitation secretion, 2 features that are strongly suggestive of apocrine differentiation.4-6 In contrast, the tumor cells of AA can be characterized by hyperchromatic nuclei, nuclear pleomorphism, mitotic figures, and a lack of decapitation secretion.1,2,6 In malignancy, erratic or poorly differentiated ductal structures may be seen,1,3-6 including papillary, cordlike, solid, or complex glandular patterns that can potentially invade the adjacent tissue without a clearly recognizable myoepithelial layer that contains them.1,3,4,6 Moreover, AA may progress with lymphatic, vascular, or neural invasion.1,13

Various stains may be used in immunohistochemical analysis to aid in the diagnosis of AA.1,5 Cytokeratin AE1/AE3, CAM5.2, epithelial membrane antigen, smooth muscle antigen, periodic acid–Schiff positivity with diastase resistance, and GCDFP-15 are useful in supporting the diagnosis of AA.2,6,10,17 Cytokeratin AE1/AE3 and CAM5.2 stain various cytokeratins to confirm the epithelial origin of the tissue.2 Epithelial membrane antigen is an antigen present on the apical surface of glandular epithelial cells that also has been used to identify epithelial cells in AA.2 Additionally, smooth muscle actin may be used to detect the myoepithelial layer of cells surrounding the apocrine glands.17 The lack of a continuous layer surrounding the secretory cells suggests invasion into the adjacent tissue.1,9,17 Periodic acid–Schiff staining with diastase resistance can be used to identify the mucin stored in the intracytoplasmic granules of apocrine cells and the lumen.3 Some stains such as GCDFP-15 may highlight cells of multiple origins (eg, apocrine and eccrine).10 However, there is the possibility that poorly differentiated AAs would fail to be identified as such even with well-established apocrine markers, which may explain the differential GCDFP-15 staining patterns in our patient’s skin and lymph node sections.1,5 Therefore, there is not a single perfect set of immunohistological criteria to aid in the diagnosis of AA.6,10,12 Fundamentally, diagnosis requires detection of primary apocrine differentiation with features such as invasion or spread to adjacent tissue to suggest malignancy and rule out an alternate primary malignant process.1,2,9,10,17

Treatment and Prognosis

Primary treatment of AA consists of wide local excision with adjuvant options that include chemotherapy and radiation.2,6 Due to the high rate of lymph node metastases at presentation (40%–50%), SLNB is recommended. A positive SLNB should be followed with complete axillary lymphadenectomy4,6; however, there is a lack of consensus regarding the role of SLNB and lymph node dissection in detecting subclinical lymph node disease, which might improve local recurrence rate and prognosis.6 Similarly, research shows variable results with adjunctive treatment such as chemotherapy or radiation therapy.6,9,13 Adjuvant treatment with chemotherapy or radiation therapy should be considered in cases with large tumor size; perineural, lymphatic, or vascular invasion; or when complete removal of the tumor is not possible due to location or size.2,6 However, neither the role nor the efficacy of such treatments in AA is well established.6,9,13

There is little information in the literature regarding the prognosis of AA. Although no specific or well-documented prognostic criteria exist, it is generally believed that patients with well-differentiated AA will have higher cure rates or lower rates of local recurrence and lymph node metastasis than patients with poorly differentiated neoplasms.3,6,10 A few small case series with long-term follow-up of patients ranging from 2 to 10 years have shown that prognosis may be favorable for AA patients despite local recurrence and regional lymph node metastasis.1,5

Conclusion

Primary AA is a rare cutaneous neoplasm that most commonly occurs in the axillae and the anogenital region. Apocrine adenocarcinoma presents with highly variable clinical and histopathological findings that make diagnosis a challenge. Clinicians should keep this entity in their differential diagnosis for patients who present with nodules arising in apocrine gland–bearing skin. Ultimately, histopathology is critical to diagnosis, and special stains are often required. To make the diagnosis, a tissue biopsy demonstrating apocrine differentiation and anaplastic features to suggest a malignant process are required. Additionally, a careful workup to rule out other diagnoses should be performed. Testing modalities that detect the presence of useful markers such as apocrine or epithelial origin should be used, and the presence of positive findings should support the diagnosis of AA. However, immunohistochemical findings should be used in the context of the patient’s clinical presentation and other available data. Treatment includes wide local excision, and lymphadenectomy is recommended in the setting of nodal spread. For aggressive tumors or metastases, excision may be followed by radiation therapy and chemotherapy.

1. Robson A, Lazar AJ, Ben Nagi J, et al. Primary cutaneous apocrine carcinoma: a clinico-pathologic analysis of 24 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2008;32:682-690.

2. Cham PM, Niehans GA, Foman N, et al. Primary cutaneous apocrine carcinoma presenting as carcinoma erysipeloides [published online ahead of print November 6, 2007]. Br J Dermatol. 2008;158:194-196.

3. Chamberlain RS, Huber K, White JC, et al. Apocrine gland carcinoma of the axilla: review of the literature and recommendations for treatment. Am J Clin Oncol. 1999;22:131-135.

4. Pucevich B, Catinchi-Jaime S, Ho J, et al. Invasive primary ductal apocrine adenocarcinoma of axilla: a case report with immunohistochemical profiling and a review of literature. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:5.

5. Paties C, Taccagni GL, Papotti M, et al. Apocrine carcinoma of the skin. a clinicopathologic, immunocytochemical, and ultrastructural study. Cancer. 1993;71:375-381.

6. Katagiri Y, Ansai S. Two cases of cutaneous apocrine ductal carcinoma of the axilla. case report and review of the literature. Dermatology. 1999;199:332-337.

7. Maury G, Guillot B, Bessis D, et al. Unusual axillary apocrine carcinoma of the skin: histological diagnostic difficulties [article in French] [published online ahead of print July 7, 2010]. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2010;137:555-559.

8. Alex G. Apocrine adenocarcinoma of the nipple: a case report. Cases J. 2008;1:88.

9. MacNeill KN, Riddell RH, Ghazarian D. Perianal apocrine adenocarcinoma arising in a benign apocrine adenoma; first case report and review of the literature. J Clin Pathol. 2005;58:217-219.

10. Shintaku M, Tsuta K, Yoshida H, et al. Apocrine adenocarcinoma of the eyelid with aggressive biological behavior: report of a case. Pathol Int. 2002;52:169-173.

11. Zehr KJ, Rubin M, Ratner L. Apocrine adenocarcinoma presenting as a large ulcerated axillary mass. Dermatol Surg. 1997;23:585-587.

12. Fernandez-Flores A. The elusive differential diagnosis of cutaneous apocrine adenocarcinoma vs. metastasis: the current role of clinical correlation. Acta Dermatovenerol Alp Panonica Adriat. 2009;18:141-142.

13. Hernandez JM, Copeland EM 3rd. Infiltrating apocrine adenocarcinoma with extramammary pagetoid spread. Am Surg. 2007;73:307-309.

14. Dhawan SS, Nanda VS, Grekin S, et al. Apocrine adenocarcinoma: case report and review of the literature. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1990;16:468-470.

15. Hügel H, Requena L. Ductal carcinoma arising from a syringocystadenoma papilliferum in a nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn. Am J Dermatopathol. 2003;25:490-493.

16. Stout AP, Cooley SG. Carcinoma of sweat glands. Cancer. 1951;4:521-536.

17. Obaidat NA, Alsaad KO, Ghazarian D. Skin adnexal neoplasms—part 2: an approach to tumours of cutaneous sweat glands [published online ahead of print August 1, 2006]. J Clin Pathol. 2007;60:145-159.

Primary apocrine adenocarcinoma (AA) is a rare cutaneous malignancy, with most of the available information about this disease consolidated from anecdotal evidence of single case reports and small case series with fewer than 30 patients.1-11 Although certain histologic and immunohistochemical features have been suggested to be useful in the diagnosis of AA, there is no clear consensus on the required pathologic criteria.1,5,6,9,10,12,13 Additionally, the clinical presentation of AA is highly variable, which further adds to the challenge of making an accurate diagnosis.1-3,5,9,10,13

Apocrine adenocarcinoma usually arises in areas of high apocrine gland density such as the axillae or anogenital region.2,4,6 It also has been reported in areas such as the scalp, ear canal, eyelids, chest, nipples, arms, wrists, and fingers.4,8,10,14-16 Apocrine adenocarcinoma in unusual locations such as the eyelid and ear canal is thought to arise from modified apocrine glands such as the Moll glands of the eyelid and the ceruminous glands of the ear canal.9,10 The presence of ectopic apocrine glands may lead to AA in atypical sites such as the wrists and fingers.5,16 The areola is an apocrine-dense area; therefore, AA may present on the nipples or within supernumerary nipples anywhere along the milk lines.4

Apocrine adenocarcinoma clinically presents as an asymptomatic to slightly painful, slowly growing, and erythematous to violaceous nodule or tumor.4,6,9 However, in a minority of cases the initial presentation consists of a cystic or ulcerated mass with overlying granulation tissue and purulent discharge.6,9,11 A wide time frame from the onset of symptoms to diagnosis has been reported, ranging from weeks to decades.4,6-8 The conventional treatment of AA is wide local excision.2,4,6,9 Although AA often presents with local lymph node metastasis at the time of diagnosis, there is no consensus on the use of sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB), nodal dissection, or adjuvant chemoradiation therapy.1,3,8,9

We report the case of a 49-year-old man with primary AA of the left axilla; the clinical and histologic features of AA as well as the appropriate diagnostic and treatment modalities also are provided.

Case Report

A 49-year-old man with a slowly growing tender mass of the left axilla of 1 year’s duration was referred to our dermatology clinic for evaluation. A review of systems revealed loss of appetite, fatigue, and a 4-month history of unintentional weight loss (15–20 lb). The patient had a history of hepatitis C virus, intravenous drug use, alcohol abuse, and cigarette smoking (1 pack daily) for many years. Additionally, the patient reported a paternal family history of numerous visceral malignancies. Examination of the left axilla revealed a 1.5×5-cm ulcerated tumor that produced serosanguineous discharge and was tender to palpation (Figure 1). Two 1-cm, firm, freely mobile subcutaneous nodules with no overlying skin changes were palpable at the medial border of the ulcerated nodule. There was no additional cervical or axillary lymphadenopathy, and a breast examination was normal.

The differential diagnosis included primary squamous cell carcinoma or adnexal neoplasm, primary breast carcinoma, lymphoma, scrofuloderma, atypical mycobacterial infection, and cutaneous metastasis from an internal malignancy. Two 4-mm punch biopsies were performed and sent for routine histopathology and bacterial, fungal, and mycobacterial tissue cultures. To exclude a primary visceral malignancy or metastasis, computed tomography of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis; positron emission tomography (PET) from the base of the skull to the thighs; colonoscopy; magnetic resonance imaging of the brain; esophagogastroduodenoscopy; and mammography were conducted. Prominent left axillary lymphadenopathy was noted on computed tomography. Additionally, PET identified extranodal spread in the left axilla, left lateral chest wall, and the left sternocleidomastoid region. Furthermore, a 1-cm hypermetabolic nodule involving the right rectus abdominus muscle was noted on the PET scan. Based on their appearance, the nodules most likely represented metastasis from a primary skin malignancy. The rest of the studies were unremarkable. Serum tumor markers including prostate-specific antigen, cancer antigen 19-9, and carcinoembryonic antigen were within reference range. Immunostaining for estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, and ERBB2 (formerly HER2/neu) was negative. The only abnormalities noted on serum chemistries were slight elevations in aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase, alkaline phosphatase, and the a-fetoprotein tumor marker, which was attributed to chronic hepatitis C infection. Bacterial, fungal, and mycobacterial tissue cultures also were negative. These results ruled out infection and suggested against a primary visceral malignancy with cutaneous metastasis.

Histopathology revealed a moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma adjacent to healthy-appearing apocrine glands (Figure 2A). The normal glands were composed of cuboidal cells with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm and prominent nuclei. The cells were arranged in a single layer in a glandular formation with prominent decapitation secretion. Adjacent to the normal apocrine glandular tissue was a focus of malignant epithelioid cells that extended to the lateral and inferior margins. The neoplastic cells were cuboidal to angulated in appearance with prominent nuclei and seemed to form ill-defined tubular or glandular structures that partially resembled apocrine glands (Figure 2B). Decapitation secretion is a feature of apocrine differentiation. Examination of additional tissue sections of the tumor did not reveal remarkable decapitation secretion in contrast to the adjacent healthy apocrine glands. Rather, a solid sheet arrangement was primarily noted in several sections (Figure 2B). Neither frequent mitoses nor prominent cellular atypia were seen, and there was no evidence of lymphatic, perineural, or vascular invasion.

|

Immunohistochemically, tumor cells reacted strongly to cytokeratin AE1/AE3 and CAM5.2, stains used to identify various cytokeratins present in epithelial tissue. Staining for epithelial membrane antigen and carcinoembryonic antigen revealed focal glandular differentiation, which further supported the epithelial origin of the neoplastic cells. Gross cystic disease fluid protein 15 (GCDFP-15) is a marker of apocrine differentiation and may indicate a carcinoma of apocrine or eccrine origin. In our case, staining for GCDFP-15 was negative in the cutaneous sections but highlighted tumor cells in 6 of 13 ipsilateral lymph nodes from locoregional metastasis. The cellular and structural morphology, immunohistochemistry, and absence of an alternative primary visceral malignancy supported the diagnosis of primary AA.

Initially the patient was not considered to be a candidate for surgery due to the rapid growth of the tumor with metastases, fatigue, weight loss, and pain. Therefore, radiation therapy was started. The patient responded well to treatment with controlled pain and resolution of the palpable mass of the left axilla. Moreover, a follow-up PET scan revealed no residual tumor and persistent, albeit decreased, axillary lymphadenopathy. As the patient’s clinical status had improved, excision of the left axillary tumor with lymph node dissection was performed 10 months after initial presentation.

In this case, the differential diagnosis consisted of various cutaneous neoplasms, primary mammary carcinoma, cutaneous metastasis, and infection. Diagnostic imaging and laboratory testing failed to identify any primary internal malignancies. Similarly, the negative cultures ruled out an infectious process. Furthermore, the axillary mass was noted to be separate from the breast tissue on physical examination and mammography. Histologically, the tumor showed features that were suggestive of an anaplastic process as well as decapitation secretion and glandular formation that clearly resembled apocrine differentiation.

Comment

Apocrine adenocarcinoma arises from apocrine sweat glands and therefore is mostly reported in areas of high apocrine gland density such as the axillae and the anogenital region.2,4,6 However, AA also has been reported in unusual locations,1,5,10,14-16 and they may arise from a pre-existing nevus sebaceous or from supernumerary nipples, which can occur anywhere along the milk lines.4,15 Apocrine adenocarcinoma most commonly arises in individuals aged 40 to 50 years.3,17 A slight male predominance has been reported but no racial predilection.1,4-6 Although a few reports have described the development of AAs within pre-existing benign tumors such as apocrine adenomas, apocrine hyperplasias, cylindromas, and nevi sebaceous, they usually are thought to arise de novo.4-6

Clinical Presentation

Apocrine adenocarcinoma is highly variable in its clinical manifestation.1,6 Most cases arise as erythematous to violaceous, firm, solitary nodules. Nonetheless, AA also can present as erythematous patches of skin resembling erysipelas and ulcerated nodules with overlying granulation tissue and purulent exudate.4,6,9,11 Although AA typically is slow growing and indolent, the time frame reported from onset to diagnosis ranges from weeks to decades.1,6,7 Most cases present asymptomatically; when symptoms do occur, the most common ones are tenderness, purulent discharge, and restricted range of motion from extremely large tumors.3,9 Incidence of lymph node metastasis is reported at 40% to 50% at the time of presentation.4,6 Additionally, AA has a high rate of local recurrence, but extranodal metastasis rarely is seen.2,6 When metastasis does occur, it is via lymphatic and hematogenous spread.6,9 Metastatic dissemination of AA may occur in the liver, lungs, bone, brain, and parotid glands, as well as the skin via intraepidermal pagetoid spread.4,6,9,13

Histopathology

The histologic characteristics essential to the diagnosis of primary AA are anaplastic differentiation and apocrine origin.1,2,9,10,17 Apocrine units include coiled secretory glands that reside in the deep dermis connecting to a straight duct that empties into the isthmus of the hair follicle.9,13 These secretory glands have a single row of cuboidal secretory cells lining the tubular component and stratified squamous epithelium lining the straight intradermal component that opens onto the hair follicle.9 Contractile myoepithelial cells surround the secretory cell layer of the gland.9,13

The cuboidal secretory cells of the apocrine gland have abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm1,4,9 and are further characterized by glandular arrangement and decapitation secretion, 2 features that are strongly suggestive of apocrine differentiation.4-6 In contrast, the tumor cells of AA can be characterized by hyperchromatic nuclei, nuclear pleomorphism, mitotic figures, and a lack of decapitation secretion.1,2,6 In malignancy, erratic or poorly differentiated ductal structures may be seen,1,3-6 including papillary, cordlike, solid, or complex glandular patterns that can potentially invade the adjacent tissue without a clearly recognizable myoepithelial layer that contains them.1,3,4,6 Moreover, AA may progress with lymphatic, vascular, or neural invasion.1,13

Various stains may be used in immunohistochemical analysis to aid in the diagnosis of AA.1,5 Cytokeratin AE1/AE3, CAM5.2, epithelial membrane antigen, smooth muscle antigen, periodic acid–Schiff positivity with diastase resistance, and GCDFP-15 are useful in supporting the diagnosis of AA.2,6,10,17 Cytokeratin AE1/AE3 and CAM5.2 stain various cytokeratins to confirm the epithelial origin of the tissue.2 Epithelial membrane antigen is an antigen present on the apical surface of glandular epithelial cells that also has been used to identify epithelial cells in AA.2 Additionally, smooth muscle actin may be used to detect the myoepithelial layer of cells surrounding the apocrine glands.17 The lack of a continuous layer surrounding the secretory cells suggests invasion into the adjacent tissue.1,9,17 Periodic acid–Schiff staining with diastase resistance can be used to identify the mucin stored in the intracytoplasmic granules of apocrine cells and the lumen.3 Some stains such as GCDFP-15 may highlight cells of multiple origins (eg, apocrine and eccrine).10 However, there is the possibility that poorly differentiated AAs would fail to be identified as such even with well-established apocrine markers, which may explain the differential GCDFP-15 staining patterns in our patient’s skin and lymph node sections.1,5 Therefore, there is not a single perfect set of immunohistological criteria to aid in the diagnosis of AA.6,10,12 Fundamentally, diagnosis requires detection of primary apocrine differentiation with features such as invasion or spread to adjacent tissue to suggest malignancy and rule out an alternate primary malignant process.1,2,9,10,17

Treatment and Prognosis

Primary treatment of AA consists of wide local excision with adjuvant options that include chemotherapy and radiation.2,6 Due to the high rate of lymph node metastases at presentation (40%–50%), SLNB is recommended. A positive SLNB should be followed with complete axillary lymphadenectomy4,6; however, there is a lack of consensus regarding the role of SLNB and lymph node dissection in detecting subclinical lymph node disease, which might improve local recurrence rate and prognosis.6 Similarly, research shows variable results with adjunctive treatment such as chemotherapy or radiation therapy.6,9,13 Adjuvant treatment with chemotherapy or radiation therapy should be considered in cases with large tumor size; perineural, lymphatic, or vascular invasion; or when complete removal of the tumor is not possible due to location or size.2,6 However, neither the role nor the efficacy of such treatments in AA is well established.6,9,13

There is little information in the literature regarding the prognosis of AA. Although no specific or well-documented prognostic criteria exist, it is generally believed that patients with well-differentiated AA will have higher cure rates or lower rates of local recurrence and lymph node metastasis than patients with poorly differentiated neoplasms.3,6,10 A few small case series with long-term follow-up of patients ranging from 2 to 10 years have shown that prognosis may be favorable for AA patients despite local recurrence and regional lymph node metastasis.1,5

Conclusion

Primary AA is a rare cutaneous neoplasm that most commonly occurs in the axillae and the anogenital region. Apocrine adenocarcinoma presents with highly variable clinical and histopathological findings that make diagnosis a challenge. Clinicians should keep this entity in their differential diagnosis for patients who present with nodules arising in apocrine gland–bearing skin. Ultimately, histopathology is critical to diagnosis, and special stains are often required. To make the diagnosis, a tissue biopsy demonstrating apocrine differentiation and anaplastic features to suggest a malignant process are required. Additionally, a careful workup to rule out other diagnoses should be performed. Testing modalities that detect the presence of useful markers such as apocrine or epithelial origin should be used, and the presence of positive findings should support the diagnosis of AA. However, immunohistochemical findings should be used in the context of the patient’s clinical presentation and other available data. Treatment includes wide local excision, and lymphadenectomy is recommended in the setting of nodal spread. For aggressive tumors or metastases, excision may be followed by radiation therapy and chemotherapy.

Primary apocrine adenocarcinoma (AA) is a rare cutaneous malignancy, with most of the available information about this disease consolidated from anecdotal evidence of single case reports and small case series with fewer than 30 patients.1-11 Although certain histologic and immunohistochemical features have been suggested to be useful in the diagnosis of AA, there is no clear consensus on the required pathologic criteria.1,5,6,9,10,12,13 Additionally, the clinical presentation of AA is highly variable, which further adds to the challenge of making an accurate diagnosis.1-3,5,9,10,13

Apocrine adenocarcinoma usually arises in areas of high apocrine gland density such as the axillae or anogenital region.2,4,6 It also has been reported in areas such as the scalp, ear canal, eyelids, chest, nipples, arms, wrists, and fingers.4,8,10,14-16 Apocrine adenocarcinoma in unusual locations such as the eyelid and ear canal is thought to arise from modified apocrine glands such as the Moll glands of the eyelid and the ceruminous glands of the ear canal.9,10 The presence of ectopic apocrine glands may lead to AA in atypical sites such as the wrists and fingers.5,16 The areola is an apocrine-dense area; therefore, AA may present on the nipples or within supernumerary nipples anywhere along the milk lines.4

Apocrine adenocarcinoma clinically presents as an asymptomatic to slightly painful, slowly growing, and erythematous to violaceous nodule or tumor.4,6,9 However, in a minority of cases the initial presentation consists of a cystic or ulcerated mass with overlying granulation tissue and purulent discharge.6,9,11 A wide time frame from the onset of symptoms to diagnosis has been reported, ranging from weeks to decades.4,6-8 The conventional treatment of AA is wide local excision.2,4,6,9 Although AA often presents with local lymph node metastasis at the time of diagnosis, there is no consensus on the use of sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB), nodal dissection, or adjuvant chemoradiation therapy.1,3,8,9

We report the case of a 49-year-old man with primary AA of the left axilla; the clinical and histologic features of AA as well as the appropriate diagnostic and treatment modalities also are provided.

Case Report

A 49-year-old man with a slowly growing tender mass of the left axilla of 1 year’s duration was referred to our dermatology clinic for evaluation. A review of systems revealed loss of appetite, fatigue, and a 4-month history of unintentional weight loss (15–20 lb). The patient had a history of hepatitis C virus, intravenous drug use, alcohol abuse, and cigarette smoking (1 pack daily) for many years. Additionally, the patient reported a paternal family history of numerous visceral malignancies. Examination of the left axilla revealed a 1.5×5-cm ulcerated tumor that produced serosanguineous discharge and was tender to palpation (Figure 1). Two 1-cm, firm, freely mobile subcutaneous nodules with no overlying skin changes were palpable at the medial border of the ulcerated nodule. There was no additional cervical or axillary lymphadenopathy, and a breast examination was normal.

The differential diagnosis included primary squamous cell carcinoma or adnexal neoplasm, primary breast carcinoma, lymphoma, scrofuloderma, atypical mycobacterial infection, and cutaneous metastasis from an internal malignancy. Two 4-mm punch biopsies were performed and sent for routine histopathology and bacterial, fungal, and mycobacterial tissue cultures. To exclude a primary visceral malignancy or metastasis, computed tomography of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis; positron emission tomography (PET) from the base of the skull to the thighs; colonoscopy; magnetic resonance imaging of the brain; esophagogastroduodenoscopy; and mammography were conducted. Prominent left axillary lymphadenopathy was noted on computed tomography. Additionally, PET identified extranodal spread in the left axilla, left lateral chest wall, and the left sternocleidomastoid region. Furthermore, a 1-cm hypermetabolic nodule involving the right rectus abdominus muscle was noted on the PET scan. Based on their appearance, the nodules most likely represented metastasis from a primary skin malignancy. The rest of the studies were unremarkable. Serum tumor markers including prostate-specific antigen, cancer antigen 19-9, and carcinoembryonic antigen were within reference range. Immunostaining for estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, and ERBB2 (formerly HER2/neu) was negative. The only abnormalities noted on serum chemistries were slight elevations in aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase, alkaline phosphatase, and the a-fetoprotein tumor marker, which was attributed to chronic hepatitis C infection. Bacterial, fungal, and mycobacterial tissue cultures also were negative. These results ruled out infection and suggested against a primary visceral malignancy with cutaneous metastasis.

Histopathology revealed a moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma adjacent to healthy-appearing apocrine glands (Figure 2A). The normal glands were composed of cuboidal cells with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm and prominent nuclei. The cells were arranged in a single layer in a glandular formation with prominent decapitation secretion. Adjacent to the normal apocrine glandular tissue was a focus of malignant epithelioid cells that extended to the lateral and inferior margins. The neoplastic cells were cuboidal to angulated in appearance with prominent nuclei and seemed to form ill-defined tubular or glandular structures that partially resembled apocrine glands (Figure 2B). Decapitation secretion is a feature of apocrine differentiation. Examination of additional tissue sections of the tumor did not reveal remarkable decapitation secretion in contrast to the adjacent healthy apocrine glands. Rather, a solid sheet arrangement was primarily noted in several sections (Figure 2B). Neither frequent mitoses nor prominent cellular atypia were seen, and there was no evidence of lymphatic, perineural, or vascular invasion.

|

Immunohistochemically, tumor cells reacted strongly to cytokeratin AE1/AE3 and CAM5.2, stains used to identify various cytokeratins present in epithelial tissue. Staining for epithelial membrane antigen and carcinoembryonic antigen revealed focal glandular differentiation, which further supported the epithelial origin of the neoplastic cells. Gross cystic disease fluid protein 15 (GCDFP-15) is a marker of apocrine differentiation and may indicate a carcinoma of apocrine or eccrine origin. In our case, staining for GCDFP-15 was negative in the cutaneous sections but highlighted tumor cells in 6 of 13 ipsilateral lymph nodes from locoregional metastasis. The cellular and structural morphology, immunohistochemistry, and absence of an alternative primary visceral malignancy supported the diagnosis of primary AA.

Initially the patient was not considered to be a candidate for surgery due to the rapid growth of the tumor with metastases, fatigue, weight loss, and pain. Therefore, radiation therapy was started. The patient responded well to treatment with controlled pain and resolution of the palpable mass of the left axilla. Moreover, a follow-up PET scan revealed no residual tumor and persistent, albeit decreased, axillary lymphadenopathy. As the patient’s clinical status had improved, excision of the left axillary tumor with lymph node dissection was performed 10 months after initial presentation.

In this case, the differential diagnosis consisted of various cutaneous neoplasms, primary mammary carcinoma, cutaneous metastasis, and infection. Diagnostic imaging and laboratory testing failed to identify any primary internal malignancies. Similarly, the negative cultures ruled out an infectious process. Furthermore, the axillary mass was noted to be separate from the breast tissue on physical examination and mammography. Histologically, the tumor showed features that were suggestive of an anaplastic process as well as decapitation secretion and glandular formation that clearly resembled apocrine differentiation.

Comment

Apocrine adenocarcinoma arises from apocrine sweat glands and therefore is mostly reported in areas of high apocrine gland density such as the axillae and the anogenital region.2,4,6 However, AA also has been reported in unusual locations,1,5,10,14-16 and they may arise from a pre-existing nevus sebaceous or from supernumerary nipples, which can occur anywhere along the milk lines.4,15 Apocrine adenocarcinoma most commonly arises in individuals aged 40 to 50 years.3,17 A slight male predominance has been reported but no racial predilection.1,4-6 Although a few reports have described the development of AAs within pre-existing benign tumors such as apocrine adenomas, apocrine hyperplasias, cylindromas, and nevi sebaceous, they usually are thought to arise de novo.4-6

Clinical Presentation

Apocrine adenocarcinoma is highly variable in its clinical manifestation.1,6 Most cases arise as erythematous to violaceous, firm, solitary nodules. Nonetheless, AA also can present as erythematous patches of skin resembling erysipelas and ulcerated nodules with overlying granulation tissue and purulent exudate.4,6,9,11 Although AA typically is slow growing and indolent, the time frame reported from onset to diagnosis ranges from weeks to decades.1,6,7 Most cases present asymptomatically; when symptoms do occur, the most common ones are tenderness, purulent discharge, and restricted range of motion from extremely large tumors.3,9 Incidence of lymph node metastasis is reported at 40% to 50% at the time of presentation.4,6 Additionally, AA has a high rate of local recurrence, but extranodal metastasis rarely is seen.2,6 When metastasis does occur, it is via lymphatic and hematogenous spread.6,9 Metastatic dissemination of AA may occur in the liver, lungs, bone, brain, and parotid glands, as well as the skin via intraepidermal pagetoid spread.4,6,9,13

Histopathology

The histologic characteristics essential to the diagnosis of primary AA are anaplastic differentiation and apocrine origin.1,2,9,10,17 Apocrine units include coiled secretory glands that reside in the deep dermis connecting to a straight duct that empties into the isthmus of the hair follicle.9,13 These secretory glands have a single row of cuboidal secretory cells lining the tubular component and stratified squamous epithelium lining the straight intradermal component that opens onto the hair follicle.9 Contractile myoepithelial cells surround the secretory cell layer of the gland.9,13

The cuboidal secretory cells of the apocrine gland have abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm1,4,9 and are further characterized by glandular arrangement and decapitation secretion, 2 features that are strongly suggestive of apocrine differentiation.4-6 In contrast, the tumor cells of AA can be characterized by hyperchromatic nuclei, nuclear pleomorphism, mitotic figures, and a lack of decapitation secretion.1,2,6 In malignancy, erratic or poorly differentiated ductal structures may be seen,1,3-6 including papillary, cordlike, solid, or complex glandular patterns that can potentially invade the adjacent tissue without a clearly recognizable myoepithelial layer that contains them.1,3,4,6 Moreover, AA may progress with lymphatic, vascular, or neural invasion.1,13

Various stains may be used in immunohistochemical analysis to aid in the diagnosis of AA.1,5 Cytokeratin AE1/AE3, CAM5.2, epithelial membrane antigen, smooth muscle antigen, periodic acid–Schiff positivity with diastase resistance, and GCDFP-15 are useful in supporting the diagnosis of AA.2,6,10,17 Cytokeratin AE1/AE3 and CAM5.2 stain various cytokeratins to confirm the epithelial origin of the tissue.2 Epithelial membrane antigen is an antigen present on the apical surface of glandular epithelial cells that also has been used to identify epithelial cells in AA.2 Additionally, smooth muscle actin may be used to detect the myoepithelial layer of cells surrounding the apocrine glands.17 The lack of a continuous layer surrounding the secretory cells suggests invasion into the adjacent tissue.1,9,17 Periodic acid–Schiff staining with diastase resistance can be used to identify the mucin stored in the intracytoplasmic granules of apocrine cells and the lumen.3 Some stains such as GCDFP-15 may highlight cells of multiple origins (eg, apocrine and eccrine).10 However, there is the possibility that poorly differentiated AAs would fail to be identified as such even with well-established apocrine markers, which may explain the differential GCDFP-15 staining patterns in our patient’s skin and lymph node sections.1,5 Therefore, there is not a single perfect set of immunohistological criteria to aid in the diagnosis of AA.6,10,12 Fundamentally, diagnosis requires detection of primary apocrine differentiation with features such as invasion or spread to adjacent tissue to suggest malignancy and rule out an alternate primary malignant process.1,2,9,10,17

Treatment and Prognosis

Primary treatment of AA consists of wide local excision with adjuvant options that include chemotherapy and radiation.2,6 Due to the high rate of lymph node metastases at presentation (40%–50%), SLNB is recommended. A positive SLNB should be followed with complete axillary lymphadenectomy4,6; however, there is a lack of consensus regarding the role of SLNB and lymph node dissection in detecting subclinical lymph node disease, which might improve local recurrence rate and prognosis.6 Similarly, research shows variable results with adjunctive treatment such as chemotherapy or radiation therapy.6,9,13 Adjuvant treatment with chemotherapy or radiation therapy should be considered in cases with large tumor size; perineural, lymphatic, or vascular invasion; or when complete removal of the tumor is not possible due to location or size.2,6 However, neither the role nor the efficacy of such treatments in AA is well established.6,9,13

There is little information in the literature regarding the prognosis of AA. Although no specific or well-documented prognostic criteria exist, it is generally believed that patients with well-differentiated AA will have higher cure rates or lower rates of local recurrence and lymph node metastasis than patients with poorly differentiated neoplasms.3,6,10 A few small case series with long-term follow-up of patients ranging from 2 to 10 years have shown that prognosis may be favorable for AA patients despite local recurrence and regional lymph node metastasis.1,5

Conclusion

Primary AA is a rare cutaneous neoplasm that most commonly occurs in the axillae and the anogenital region. Apocrine adenocarcinoma presents with highly variable clinical and histopathological findings that make diagnosis a challenge. Clinicians should keep this entity in their differential diagnosis for patients who present with nodules arising in apocrine gland–bearing skin. Ultimately, histopathology is critical to diagnosis, and special stains are often required. To make the diagnosis, a tissue biopsy demonstrating apocrine differentiation and anaplastic features to suggest a malignant process are required. Additionally, a careful workup to rule out other diagnoses should be performed. Testing modalities that detect the presence of useful markers such as apocrine or epithelial origin should be used, and the presence of positive findings should support the diagnosis of AA. However, immunohistochemical findings should be used in the context of the patient’s clinical presentation and other available data. Treatment includes wide local excision, and lymphadenectomy is recommended in the setting of nodal spread. For aggressive tumors or metastases, excision may be followed by radiation therapy and chemotherapy.

1. Robson A, Lazar AJ, Ben Nagi J, et al. Primary cutaneous apocrine carcinoma: a clinico-pathologic analysis of 24 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2008;32:682-690.

2. Cham PM, Niehans GA, Foman N, et al. Primary cutaneous apocrine carcinoma presenting as carcinoma erysipeloides [published online ahead of print November 6, 2007]. Br J Dermatol. 2008;158:194-196.

3. Chamberlain RS, Huber K, White JC, et al. Apocrine gland carcinoma of the axilla: review of the literature and recommendations for treatment. Am J Clin Oncol. 1999;22:131-135.

4. Pucevich B, Catinchi-Jaime S, Ho J, et al. Invasive primary ductal apocrine adenocarcinoma of axilla: a case report with immunohistochemical profiling and a review of literature. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:5.

5. Paties C, Taccagni GL, Papotti M, et al. Apocrine carcinoma of the skin. a clinicopathologic, immunocytochemical, and ultrastructural study. Cancer. 1993;71:375-381.

6. Katagiri Y, Ansai S. Two cases of cutaneous apocrine ductal carcinoma of the axilla. case report and review of the literature. Dermatology. 1999;199:332-337.

7. Maury G, Guillot B, Bessis D, et al. Unusual axillary apocrine carcinoma of the skin: histological diagnostic difficulties [article in French] [published online ahead of print July 7, 2010]. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2010;137:555-559.

8. Alex G. Apocrine adenocarcinoma of the nipple: a case report. Cases J. 2008;1:88.

9. MacNeill KN, Riddell RH, Ghazarian D. Perianal apocrine adenocarcinoma arising in a benign apocrine adenoma; first case report and review of the literature. J Clin Pathol. 2005;58:217-219.

10. Shintaku M, Tsuta K, Yoshida H, et al. Apocrine adenocarcinoma of the eyelid with aggressive biological behavior: report of a case. Pathol Int. 2002;52:169-173.

11. Zehr KJ, Rubin M, Ratner L. Apocrine adenocarcinoma presenting as a large ulcerated axillary mass. Dermatol Surg. 1997;23:585-587.

12. Fernandez-Flores A. The elusive differential diagnosis of cutaneous apocrine adenocarcinoma vs. metastasis: the current role of clinical correlation. Acta Dermatovenerol Alp Panonica Adriat. 2009;18:141-142.

13. Hernandez JM, Copeland EM 3rd. Infiltrating apocrine adenocarcinoma with extramammary pagetoid spread. Am Surg. 2007;73:307-309.

14. Dhawan SS, Nanda VS, Grekin S, et al. Apocrine adenocarcinoma: case report and review of the literature. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1990;16:468-470.

15. Hügel H, Requena L. Ductal carcinoma arising from a syringocystadenoma papilliferum in a nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn. Am J Dermatopathol. 2003;25:490-493.

16. Stout AP, Cooley SG. Carcinoma of sweat glands. Cancer. 1951;4:521-536.

17. Obaidat NA, Alsaad KO, Ghazarian D. Skin adnexal neoplasms—part 2: an approach to tumours of cutaneous sweat glands [published online ahead of print August 1, 2006]. J Clin Pathol. 2007;60:145-159.

1. Robson A, Lazar AJ, Ben Nagi J, et al. Primary cutaneous apocrine carcinoma: a clinico-pathologic analysis of 24 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2008;32:682-690.

2. Cham PM, Niehans GA, Foman N, et al. Primary cutaneous apocrine carcinoma presenting as carcinoma erysipeloides [published online ahead of print November 6, 2007]. Br J Dermatol. 2008;158:194-196.

3. Chamberlain RS, Huber K, White JC, et al. Apocrine gland carcinoma of the axilla: review of the literature and recommendations for treatment. Am J Clin Oncol. 1999;22:131-135.

4. Pucevich B, Catinchi-Jaime S, Ho J, et al. Invasive primary ductal apocrine adenocarcinoma of axilla: a case report with immunohistochemical profiling and a review of literature. Dermatol Online J. 2008;14:5.

5. Paties C, Taccagni GL, Papotti M, et al. Apocrine carcinoma of the skin. a clinicopathologic, immunocytochemical, and ultrastructural study. Cancer. 1993;71:375-381.

6. Katagiri Y, Ansai S. Two cases of cutaneous apocrine ductal carcinoma of the axilla. case report and review of the literature. Dermatology. 1999;199:332-337.

7. Maury G, Guillot B, Bessis D, et al. Unusual axillary apocrine carcinoma of the skin: histological diagnostic difficulties [article in French] [published online ahead of print July 7, 2010]. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2010;137:555-559.

8. Alex G. Apocrine adenocarcinoma of the nipple: a case report. Cases J. 2008;1:88.

9. MacNeill KN, Riddell RH, Ghazarian D. Perianal apocrine adenocarcinoma arising in a benign apocrine adenoma; first case report and review of the literature. J Clin Pathol. 2005;58:217-219.

10. Shintaku M, Tsuta K, Yoshida H, et al. Apocrine adenocarcinoma of the eyelid with aggressive biological behavior: report of a case. Pathol Int. 2002;52:169-173.

11. Zehr KJ, Rubin M, Ratner L. Apocrine adenocarcinoma presenting as a large ulcerated axillary mass. Dermatol Surg. 1997;23:585-587.

12. Fernandez-Flores A. The elusive differential diagnosis of cutaneous apocrine adenocarcinoma vs. metastasis: the current role of clinical correlation. Acta Dermatovenerol Alp Panonica Adriat. 2009;18:141-142.

13. Hernandez JM, Copeland EM 3rd. Infiltrating apocrine adenocarcinoma with extramammary pagetoid spread. Am Surg. 2007;73:307-309.

14. Dhawan SS, Nanda VS, Grekin S, et al. Apocrine adenocarcinoma: case report and review of the literature. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1990;16:468-470.

15. Hügel H, Requena L. Ductal carcinoma arising from a syringocystadenoma papilliferum in a nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn. Am J Dermatopathol. 2003;25:490-493.

16. Stout AP, Cooley SG. Carcinoma of sweat glands. Cancer. 1951;4:521-536.

17. Obaidat NA, Alsaad KO, Ghazarian D. Skin adnexal neoplasms—part 2: an approach to tumours of cutaneous sweat glands [published online ahead of print August 1, 2006]. J Clin Pathol. 2007;60:145-159.

Practice Points

- Primary apocrine adenocarcinoma (AA) is a rare cutaneous malignancy with metastatic potential.

It arises in areas of high apocrine gland density including the axillae and anogenital region. - Apocrine adenocarcinoma must be differentiated from various infections and cutaneous metastases from internal malignancies.

- Primary apocrine differentiation with invasion to adjacent tissue is a key histopathologic feature of AA.