User login

Many serum biomarkers have been identified in recent years with a wide range of potential applications, including diagnosis of local and systemic infections, differentiation of bacterial and fungal infections from viral syndromes or noninfectious conditions, prognostic stratification of patients, and enhanced management of antibiotic therapy. Currently, there are at least 178 serum biomarkers that have potential roles to guide antibiotic therapy, and among these, procalcitonin has been the most extensively studied biomarker.[1, 2]

Procalcitonin is the prohormone precursor of calcitonin that is expressed primarily in C cells of the thyroid gland. Conversion of procalcitonin to calcitonin is inhibited by various cytokines and bacterial endotoxins. Procalcitonin's primary diagnostic utility is thought to be in establishing the presence of bacterial infections, because serum procalcitonin levels rise and fall rapidly in bacterial infections.[3, 4, 5] In healthy individuals, procalcitonin levels are very low. In systemic infections, including sepsis, procalcitonin levels are generally greater than 0.5 to 2 ng/mL, but often reach levels 10 ng/mL, which correlates with severity of illness and a poor prognosis. In patients with respiratory tract infections, procalcitonin levels are less elevated, and a cutoff of 0.25 ng/mL seems to be most predictive of a bacterial respiratory tract infection requiring antibiotic therapy.[6, 7, 8] Procalcitonin levels decrease to <0.25 ng/mL as infection resolves, and a decline in procalcitonin level may guide decisions about discontinuation of antibiotic therapy.[5]

The purpose of this systematic review was to synthesize comparative studies examining the use of procalcitonin to guide antibiotic therapy in patients with suspected local or systemic infections in different patient populations. We are aware of 6 previously published systematic reviews evaluating the utility of procalcitonin guidance in the management of infections.[9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14] Our systematic review included more studies and pooled patients into the most clinically similar groups compared to other systematic reviews.

METHODS

This review is based on a comparative effectiveness review prepared for the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality's Effective Health Care Program.[15] A standard protocol consistent with the Methods Guide for Effectiveness and Comparative Effectiveness Reviews[16] was followed. A detailed description of the methods is available online (

Study Question

In selected populations of patients with suspected local or systemic infection, what are the effects of using procalcitonin measurement plus clinical criteria for infection to guide initiation, intensification, and/or discontinuation of antibiotic therapy when compared to clinical criteria for infection alone?

Search Strategy

MEDLINE and EMBASE were searched from January 1, 1990 through December 16, 2011, and the Cochrane Controlled Trials register was searched with no date restriction for randomized and nonrandomized comparative studies using the following search terms: procalcitonin AND chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; COPD; critical illness; critically ill; febrile neutropenia; ICU; intensive care; intensive care unit; postoperative complication(s); postoperative infection(s); postsurgical infection(s); sepsis; septic; surgical wound infection; systemic inflammatory response syndrome OR postoperative infection. In addition, a search for systematic reviews was conducted in MEDLINE, the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, and Web sites of the National Institute for Clinical Excellence, the National Guideline Clearinghouse, and the Health Technology Assessment Programme. Gray literature, including databases with regulatory information, clinical trial registries, abstracts and conference papers, grants and federally funded research, and manufacturing information was searched from January 1, 2006 to June 28, 2011.

Study Selection

A single reviewer screened abstracts and selected studies looking at procalcitonin‐guided antibiotic therapy. Second and third reviewers were consulted to screen articles when needed. Studies were included if they fulfilled all of the following criteria: (1) randomized, controlled trial or nonrandomized comparative study; (2) adult and/or pediatric patients with known or suspected local or systemic infection, including critically ill patients with sepsis syndrome or ventilator‐associated pneumonia, adults with respiratory tract infections, neonates with sepsis, children with fever of unknown source, and postoperative patients at risk of infection; (3) interventions included initiation, intensification, and/or discontinuation of antibiotic therapy guided by procalcitonin plus clinical criteria; (4) primary outcomes included antibiotic usage (antibiotic prescription rate, total antibiotic exposure, duration of antibiotic therapy, and days without antibiotic therapy); and (5) secondary outcomes included morbidity (antibiotic adverse events, hospital and/or intensive care unit length of stay), mortality, and quality of life.

Studies with any of the following criteria were excluded: published in non‐English language, not reporting primary data from original research, not a randomized, controlled trial or nonrandomized comparative study, not reporting relevant outcomes.

Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

A single reviewer abstracted data and a second reviewer confirmed accuracy. Disagreements between reviewers were resolved by group discussion among the research team and final quality rating was assigned by consensus adjudication. Data elements were abstracted into the following categories: quality assessment, applicability and clinical diversity assessment, and outcome assessment. Quality of included studies was assessed using the US Preventive Services Task Force framework[17] by at least 2 independent reviewers. Three quality categories were used: good, fair, and poor.

Data Synthesis and Analysis

The decision to incorporate formal data synthesis in this review was made after completing the formal literature search, and the decision to pool studies was based on the specific number of studies with similar questions and outcomes. If a meta‐analysis could be performed, subgroup and sensitivity analyses were based on clinical similarity of available studies and reporting of mean and standard deviation. The pooling method involved inverse variance weighting and a random effects model.

The strength of evidence was graded using the Methods Guide,[16] a system based on the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation Working Group.[18] The following domains were addressed: risk of bias, consistency, directness, and precision. The overall strength of evidence was graded as high, moderate, low, or insufficient. The final strength of evidence grading was made by consensus adjudication among the authors.

RESULTS

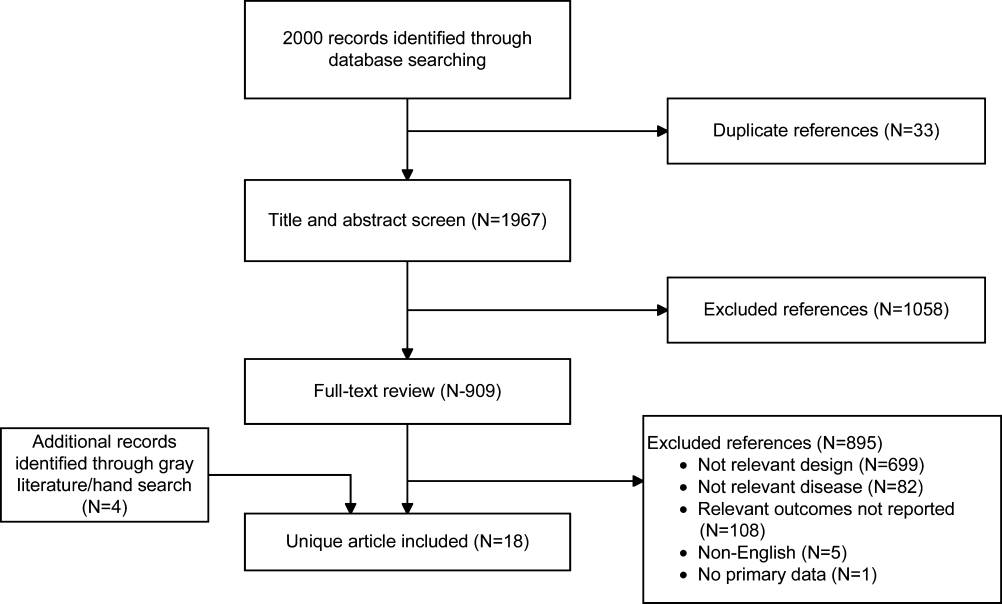

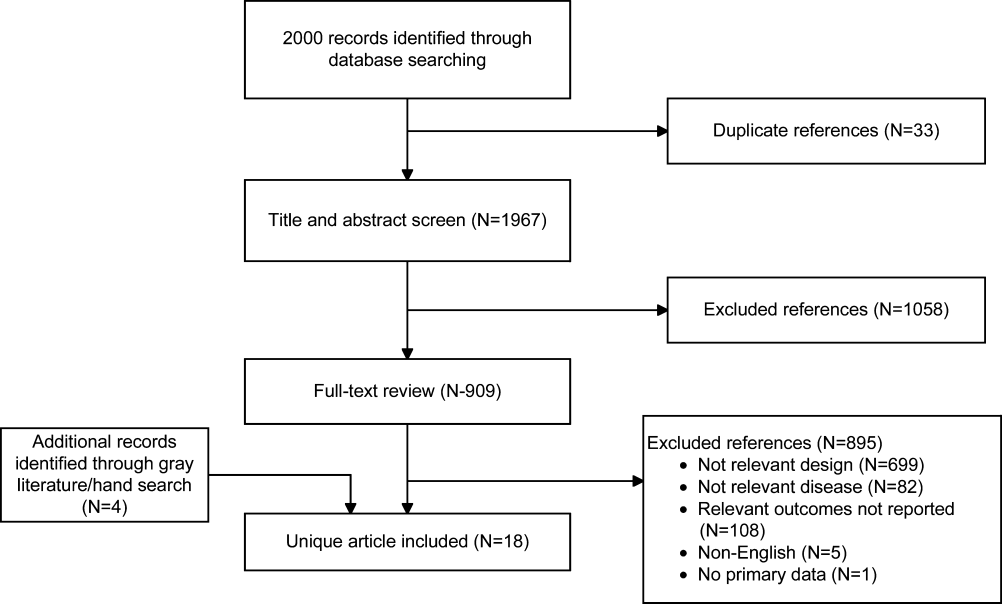

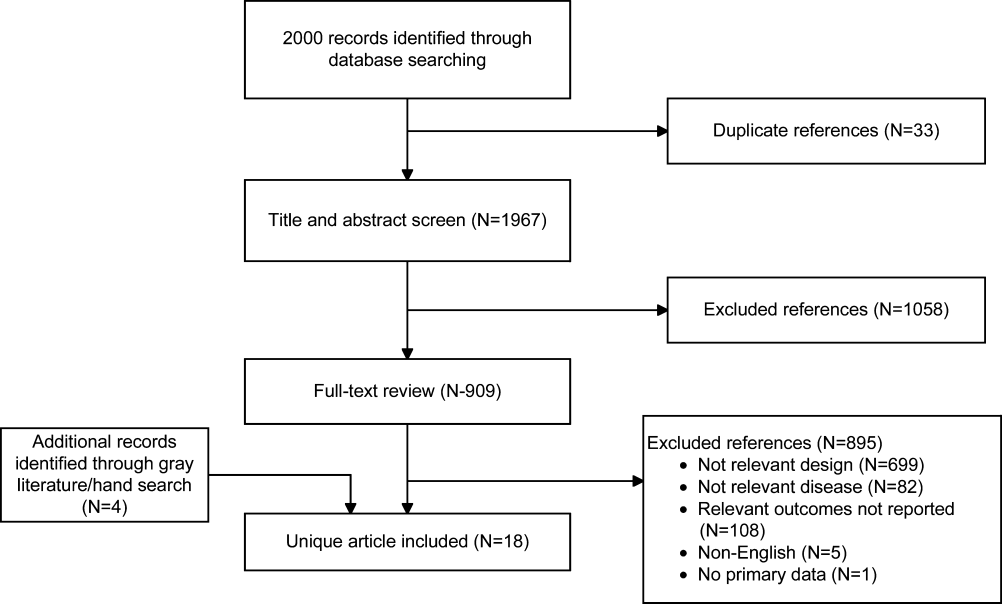

Of the 2000 studies identified through the literature search, 1986 were excluded and 14 studies[19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32] were included. Search of gray literature yielded 4 published studies.[33, 34, 35, 36] A total of 18 randomized, controlled trials comparing procalcitonin guidance to use of clinical criteria alone to manage antibiotic therapy in patients with infections were included. The PRISMA diagram (Figure 1) depicts the flow of search screening and study selection. We sought, but did not find, nonrandomized comparative studies of populations, comparisons, interventions, and outcomes that were not adequately studied in randomized, controlled trials.

Data were pooled into clinically similar groups that were reviewed separately: (1) adult intensive care unit (ICU) patients, including patients with ventilator‐associated pneumonia; (2) adult patients with respiratory tract infections; (3) neonates with suspected sepsis; (4) children between 1 to 36 months of age with fever of unknown source; and (5) postoperative patients at risk of infection. Tables summarizing study quality and outcome measures with strength of evidence are available online (

| Outcome | Author, Year | N | PCT‐Guided Therapya | Controla | Difference PCT‐CTRL (95% CI) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||

| Critically ill adult patients: procalcitonin‐guided antibiotic discontinuation | ||||||

| ABT Duration, d | Hochreiter, 2009[22] | 110 | 5.9 | 7.9 | 2.0 (2.5 to 1.5) | <0.001 |

| Nobre, 2008[19] | 79 | 66 | 9.5 (ITT), 10 (PP) | 2.6 (5.5 to 0.3), 3.2 (1.1 to5.4) | 0.15, 0.003 | |

| Schroeder, 2009[20] | 27 | 6.6 | 8.3 | 1.7 (2.4 to 1.0) | <0.001 | |

| Stolz, 2009[21] | 101 | 10 (616)b | 15 (1023)b | 5 | 0.049 | |

| Bouadma, 2010[23] | 621 | 10.3 | 13.3 | 3.0 (4.20 to 1.80) | <0.0001 | |

| Days without ABTs, day 28 | Nobre, 2008[19] | 79 | 15.3, 17.4 | 13, 13.6 | 2.3 (5.9 to 1.8), 3.8 (0.1 to 7.5)c | 0.28, 0.04 |

| Stolz, 2009[21] | 101 | 13 (221)b | 9.5 (1.517)b | 3.5 | 0.049 | |

| Bouadma, 2010[23] | 621 | 14.3 | 11.6 | 2.7 (1.4 to 4.1) | <0.001 | |

| Total ABT exposured | Nobre, 2008[19] | 79 | 541 | 644 | 1.1e (0.9 to 1.3), 1.3e (1.1 to 1,5)c | 0.07, 0.0002 |

| 504 | 655 | |||||

| Stolz, 2009[21] | 101 | 1077 | 1341 | |||

| Bouadma, 2010[23]d | 621 | 653 | 812 | 159 (185 to 131) | <0.001 | |

| Critically ill adult patients: procalcitonin‐guided antibiotic intensification | ||||||

| ABT duration, days | Jensen, 2011[33] | 1200 | 6 (311)b | 4 (310)b | NR | NR |

| Days spent in ICU on 3 ABTs | Jensen, 2011[33] | 1200 | 3570/5447 (65.5%) | 2721/4717 (57.7%) | 7.9% (6.0 to 9.7) | 0.002 |

| Adult patients with respiratory tract infections | ||||||

| ABT duration, da | Schuetz, 2009[2][5] | 1359 | 5.7 | 8.7 | 3.0 | |

| Christ‐Crain, 2004[30] | 243 | 10.9 | 12.8 | 1.9 (3.1 to 0.7) | 0.002 | |

| Kristoffersen, 2009[26] | 210 | 5.1 | 6.8 | 1.7 | ||

| Briel, 2008[27] | 458 | 6.2 | 7.1 | 1.0 (1.7 to 0.4) | <0.05 | |

| Long, 20113[5] | 162 | 5 (36)f | 7 (59)f | 2.0 | <0.001 | |

| Burkhardt, 2010[34] | 550 | 7.8 | 7.7 | 0.1 (0.7 to 0.9) | 0.8 | |

| Christ‐Crain, 2006[29] | 302 | 5.8 | 12.9 | 7.1(8.4 to 5.8) | <0.0001 | |

| Antibiotic prescription rate, % | Schuetz, 2009[2][5] | 1359 | 506/671 (75.4%) | 603/688 (87.6%) | 12.2% (16.3 to 8.1) | <0.05 |

| Christ‐Crain, 2004[30] | 243 | 55/124 (44.4%) | 99/119 (83.2%) | 38.8% (49.9 to 27.8) | <0.0001 | |

| Kristoffersen, 2009[26] | 210 | 88/103 (85.4%) | 85/107 (79.4%) | 6.0% (4.3 to 16.2) | 0.25 | |

| Briel, 2008[27] | 458 | 58/232 (25.0%) | 219/226 (96.9%) | 72% (78 to 66) | <0.05 | |

| Long, 20113[5] | 162 | NR (84.4%) | NR (97.5%) | 13.1% | 0.004 | |

| Stolz, 2007[28] | 208 | 41/102 (40.2%) | 76/106 (71.7%) | 31.5% (44.3 to 18.7) | <0.0001 | |

| Christ‐Crain, 2006[29] | 302 | 128/151 (84.8%) | 149/151 (98.79%) | 13.9% (19.9 to 7.9) | <0.0001 | |

| Burkhardt, 2010[34] | 550 | 84/275 (30.5%) | 89/275 (32.4%) | 1.8% (9.6 to 5.9) | 0.701 | |

| Total ABT exposure | Stolz, 2007[28] | 208 | NR | NR | 31.5% (18.7 to 44.3) | <0.0001 |

| Long, 20113[5] | 162 | NR | NR | NR | ||

| Christ‐Crain, 2006[29] | 302 | 136g | 323g | |||

| Christ‐Crain, 2004[30] | 243 | 332g | 661g | |||

| Neonates with sepsis | ||||||

| ABTs 72 hours, % | Stocker, 2010[31] | All neonates (N=121) | 33/60 (55%) | 50/61 (82%) | 27.0 (42.8 to 11.1) | 0.002 |

| Infection proven/probably (N=21) | 9/9 (100%) | 12/12 (100%) | 0% (0 to 0) | NA | ||

| Infection possible (N=40) | 13/21 (61.9%) | 19/19 (100%) | 38.1 (58.9 to 17.3) | 0.003 | ||

| Infection unlikely (N=60) | 11/30 (36.7%) | 19/30 (63.3%) | 26.6 (51.1 to 2.3) | 0.038 | ||

| ABT duration, h | Stocker, 2010[31] | All neonates (N=121) | 79.1 | 101.5 | 22.4 | 0.012 |

| Infection proven/probably (N=21) | 177.8 | 170.8 | 7 | NSS | ||

| Infection possible (N=40) | 83.4 | 111.5 | 28.1 | <0.001 | ||

| Infection unlikely (N=60) | 46.5 | 67.4 | 20.9 | 0.001 | ||

| Children ages 136 months with fever of unknown source | ||||||

| Antibiotic prescription rate, % | Manzano, 2010[36] | All children (N=384) | 48/192 (25%) | 54/192 (28.0%) | 3.1 (12.0 to 5.7) | 0.49 |

| No SBI or neutropenia (N=312) | 14/158 (9%) | 16/154 (10%) | 1.5 (8.1 to 5.0) | 0.65 | ||

| Adult postoperative patients at risk of infection | ||||||

| ABT duration, d | Chromik, 2006[32] | All patients (N=20) | 5.5 | 9 | 3.5 | 0.27 |

| Outcome | Author, Year | N | PCTa | Controla | Difference, PCT‐CTRL (95% CI) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||

| Critically ill adult patients: procalcitonin‐guided antibiotic discontinuation | ||||||

| ICU LOS, days | Hochreiter, 2009[22] | 110 | 15.5 | 17.7 | 2.2 | 0.046 |

| Nobre, 2008[19] | 79 | 4 | 7 | 4.6 (8.2 to 1.0) | 0.02 | |

| Schroeder, 2009[20] | 27 | 16.4 | 16.7 | 0.3 (5.6 to 5.0) | NSS | |

| Bouadma, 2010[23] | 621 | 15.9 | 14.4 | 1.5 (0.9 to 3.1) | 0.23 | |

| Hospital LOS, days | Nobre, 2008[19] | 79 | 17 | 23.5 | 2.5 (6.5 to 1.5) | 0.85 |

| Stolz, 2009[21] | 101 | 26 (721)b | 26 (16.822.3)b | 0 | 0.15 | |

| Bouadma, 2010[23] | 621 | 26.1 | 26.4 | 0.3 (3.2 to 2.7) | 0.87 | |

| ICU‐free days alive, 128 | Stolz, 2009[21] | 101 | 10 (018)b | 8.5 (018)c | 1.5 | 0.53 |

| SOFA day 28 | Bouadma, 2010[23] | 621 | 1.5 | 0.9 | 0.6 (0.0, 1.1) | 0.037 |

| SOFA score max | Schroeder, 2009[20] | 27 | 7.3 | 8.3 | 8.1 (4.1 to 1.7) | NSS |

| SAPS II score | Hochreiter, 2009[22] | 110 | 40.1 | 40.5 | 0.4 (6.4 to 5.6) | >0.05 |

| Days without MV | Stolz, 2009[21] | 101 | 21 (224)b | 19 (8.522.5)b | 2.0 | 0.46 |

| Bouadma, 2010[23] | 621 | 16.2 | 16.9 | 0.7 (2.4 to 1.1) | 0.47 | |

| Critically ill adult patients: procalcitonin‐guided antibiotic intensification | ||||||

| ICU LOS, da | Svoboda, 2007[24] | 72 | 16.1 | 19.4 | 3.3 (7.0 to 0.4) | 0.09 |

| Jensen, 2011[33] | 1200 | 6 (312)b | 5 (311)b | 1 | 0.004 | |

| SOFA scorea | Svoboda, 2007[24] | 72 | 7.9 | 9.3 | 1.4 (2.8 to 0.0) | 0.06 |

| Days on MVa | Svoboda, 2007[24] | 72 | 10.3 | 13.9 | 3.6 (7.6 to 0.4) | 0.08 |

| Jensen, 2011[33] | 1200 | 3569 (65.5%) | 2861 (60.7%) | 4.9% (3 to 6.7) | <0.0001 | |

| Percent days in ICU with GFR <60 | Jensen, 2011[33] | 1200 | 2796 (51.3%) | 2187 (46.4%) | 5.0 % (3.0 to 6.9) | <0.0001 |

| Adult patients with respiratory tract infections | ||||||

| Hospital LOS, da | Schuetz, 2009[2][5] | 1359 | 9.4 | 9.2 | 0.2 | |

| Christ‐Crain, 2004[30] | 224 | 10.78.9 | 11.210.6 | 0.5 (3.0 to 2.0) | 0.69 | |

| Kristoffersen, 2009[26] | 210 | 5.9 | 6.7 | 0.8 | 0.22 | |

| Stolz, 2007[28] | 208 | 9 (115)b | 10 (115)b | 1 | 0.96 | |

| Christ‐Crain, 2006[29] | 302 | 12.09.1 | 13.09.0 | 1 (3.0 to 1.0) | 0.34 | |

| ICU admission, % | Schuetz, 2009[2][5] | 1359 | 43/671 (6.4%) | 60/688 (8.7%) | 2.3% (5.2 to 0.4) | 0.12 |

| Christ‐Crain, 2004[30] | 224 | 5/124 (4.0%) | 6/119 (5.0%) | 1.0% (6.2 to 4.2) | 0.71 | |

| Kristoffersen, 2009[26] | 210 | 7/103 (6.8%) | 5/107 (4.7%) | 2.1% (4.2 to 8.4) | 0.51 | |

| Stolz, 2007[28] | 208 | 8/102 (7.8%) | 11/106 (10.4%) | 2.5% (10.3 to 5.3) | 0.53 | |

| Christ‐Crain, 2006[29] | 302 | 20/151 (13.2%) | 21/151 (13.94%) | 0.7% (8.4 to 7.1) | 0.87 | |

| Antibiotic adverse events | Schuetz, 2009[2][5]c | 1359 | 133/671 (19.8%) | 193/688 (28.1%) | 8.2% (12.7 to 3.7) | |

| Briel, 2008[27]d | 458 | 2.34.6 days | 3.66.1 days | 1.1 days (2.1 to 0.1) | <0.05 | |

| Burkhardt, 2010[34]e | 550 | 11 /59 (18.6%) | 16/101 (15.8%) | 2.8% (9.4 to 15.0) | 0.65 | |

| Restricted activity, df | Briel, 2008[27] | 458 | 8.73.9 | 8.63.9 | 0.2 (0.4 to 0.9) | >0.05 |

| Burkhardt, 2010[34] | 550 | 9.1 | 8.8 | 0.25 (0.52 to 1.03) | >0.05 | |

| Neonates with sepsis | ||||||

| Recurrence of infection | Stocker, 2010[31] | 121 | 32% | 39% | 7 | 0.45 |

| Children ages 136 months with fever of unknown source | ||||||

| Hospitalization rate | Manzano, 2010[36] | All children (N=384) | 50/192 (26%) | 48/192 (25%) | 1 (8 to 10) | 0.81 |

| No SBI or neutropenia (N=312) | 16/158 (10%) | 11/154 (7%) | 3 (3 to 10) | 0.34 | ||

| Adult postoperative patients at risk of infection | ||||||

| Hospital LOS, days | Chromik, 2006[32] | 20 | 18 | 30 | 12 | 0.057 |

| Local wound infection, % | Chromik, 2006[32] | 20 | 1/10 | 2/10 | 10 (41.0 to 21.0) | 0.53 |

| Systemic infection, % | Chromik, 2006[32] | 20 | 3/10 | 7/10 | 40.0 (80.2 to 0.2) | 0.07 |

| Sepsis/SIRS, % | Chromik, 2006[32] | 20 | 2/10 | 8/10 | 60.0 (95.1 to 24.9) | 0.007 |

| Mortality | Mortality | Difference | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | Author, Year | N | PCT‐Guided Therapy | Control | PCT‐CTRL (95% CI) | P Value |

| ||||||

| Critically ill adult patients: procalcitonin‐guided antibiotic discontinuation | ||||||

| 28‐day mortality | Nobre, 2008[19] | 79 | 8/39 (20.5%) | 8/40 (20.0%) | 0.5 (17.2 to 18.2), | 0.95 |

| 5/31 (16.1%) | 6/37 (16.2%) | 0.1 (17.7 to 17.5)a | 0.99 | |||

| Stolz, 2009[21] | 101 | 8/51 (15.7%) | 12/50 (24.0%) | 8.3 (23.8 to 7.2) | 0.29 | |

| Bouadma, 2010[23] | 621 | 65/307 (21.2%) | 64/314 (20.4%) | 0.8 (5.6 to 7.2) | 0.81 | |

| 60‐day mortality | Bouadma, 2010[23] | 621 | 92/307 (30.0%) | 82/314 (26.1%) | 3.9 (3.2 to 10.9) | 0.29 |

| In‐hospital mortality | Nobre, 2008[19] | 79 | 9/39 (23.1%) | 9/40 (22.5%) | 0.6 (17.9 to 19.1) | 0.95 |

| 6/31 (19.4%) | 7/37 (18.9%) | 0.4+ (18.3 to 19.2) | 0.96 | |||

| Stolz, 2009[21] | 101 | 10/51 (19.6%) | 14/50 (28.0%) | 8.4, (24.9 to 8.1) | 0.32 | |

| Hochreiter, 2009[22] | 110 | 15/57 (26.3%) | 14/53 (26.4%) | 0.1, (16.6 to 16.4) | 0.99 | |

| Schroeder, 2009[20] | 27 | 3/14 (21.4%) | 3/13 (23.1%) | 1.7, (33.1 to 29.8) | 0.92 | |

| Critically ill adult patients: procalcitonin‐guided antibiotic intensification | ||||||

| 28‐day mortality | Svoboda, 2007[24] | 72 | 10/38 (26.3%) | 13/34 (38.2%) | 11.9 (33.4 to 9.6) | 0.28 |

| 28‐day mortality | Jensen, 2011[33] | 1200 | 190/604 (31.5%) | 191/596 (32.0%) | 0.6 (4.7 to 5.9) | 0.83 |

| Adult patients with respiratory tract infections | ||||||

| 6‐month mortality | Stolz, 2007[28] | 208 | 5/102 (4.9%) | 9/106 (8.5%) | 3.6% (10.3 to 3.2%) | 0.30 |

| 6‐week mortality | Christ‐Crain, 2006[29] | 302 | 18/151 (11.9%) | 20/151 (13.2%) | 1.3% (8.8 to 6.2) | 0.73 |

| 28‐day mortality | Christ‐Crain, 2004[30] | 243 | 4/124(3.2%) | 4/119 (3.4%) | 0.1% (4.6 to 4.4) | 0.95 |

| Schuetz, 2009 (30‐day)[25] | 1359 | 34/671(5.1%) | 33/688(4.8%) | 0.3% (2.1 to 2.5) | 0.82 | |

| Briel, 2008[27] | 458 | 0/231(0%) | 1/224 (0.4%) | 0.4% (1.3 to 0.4) | 0.31 | |

| Burkhardt, 2010[34] | 550 | 0/275(0%) | 0/275 (0%) | 0 | ||

| Kristoffersen, 2009[26] | 210 | 2/103(1.9%) | 1/107 (0.9%) | 1.0% (2.2 to 4.2) | 0.54 | |

| Long, 20113[5] | 162 | 0/81 (0%) | 0/81 (0%) | 0 | ||

| Neonates with sepsis | ||||||

| Mortality (in‐hospital) | Stocker, 2010[31] | 121 | 0% | 0% | 0 (0 to 0) | NA |

| Children ages 136 months with fever of unknown source | ||||||

| Mortality | Manzano, 2010[36] | 384 | All children | 0% | 0% | 0 (0 to 0) |

| Adult postoperative patients at risk of infection | ||||||

| Mortality | Chromik, 2006[32] | 20 | 1/10 (10%) | 3/10 (30%) | 20 (54.0 to 14.0) | 0.07 |

Adult ICU Patients: Procalcitonin‐Guided Antibiotic Discontinuation

Five studies[19, 20, 21, 22, 23] (N=938) addressed procalcitonin‐guided discontinuation of antibiotic therapy in adult ICU patients. Four studies conducted superiority analyses for mortality with procalcitonin‐guided therapy, whereas 1 study conducted a noninferiority analysis. Absolute procalcitonin values for discontinuation of antibiotics ranged from 0.25 to 1 ng/mL. Physicians in control groups administered antibiotics according to their standard practice.

Antibiotic Usage

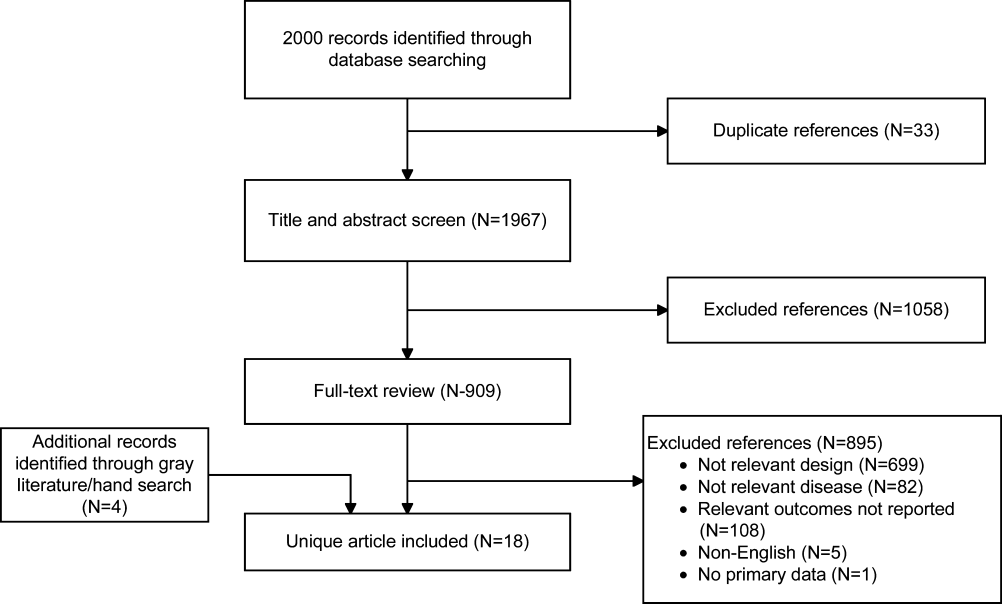

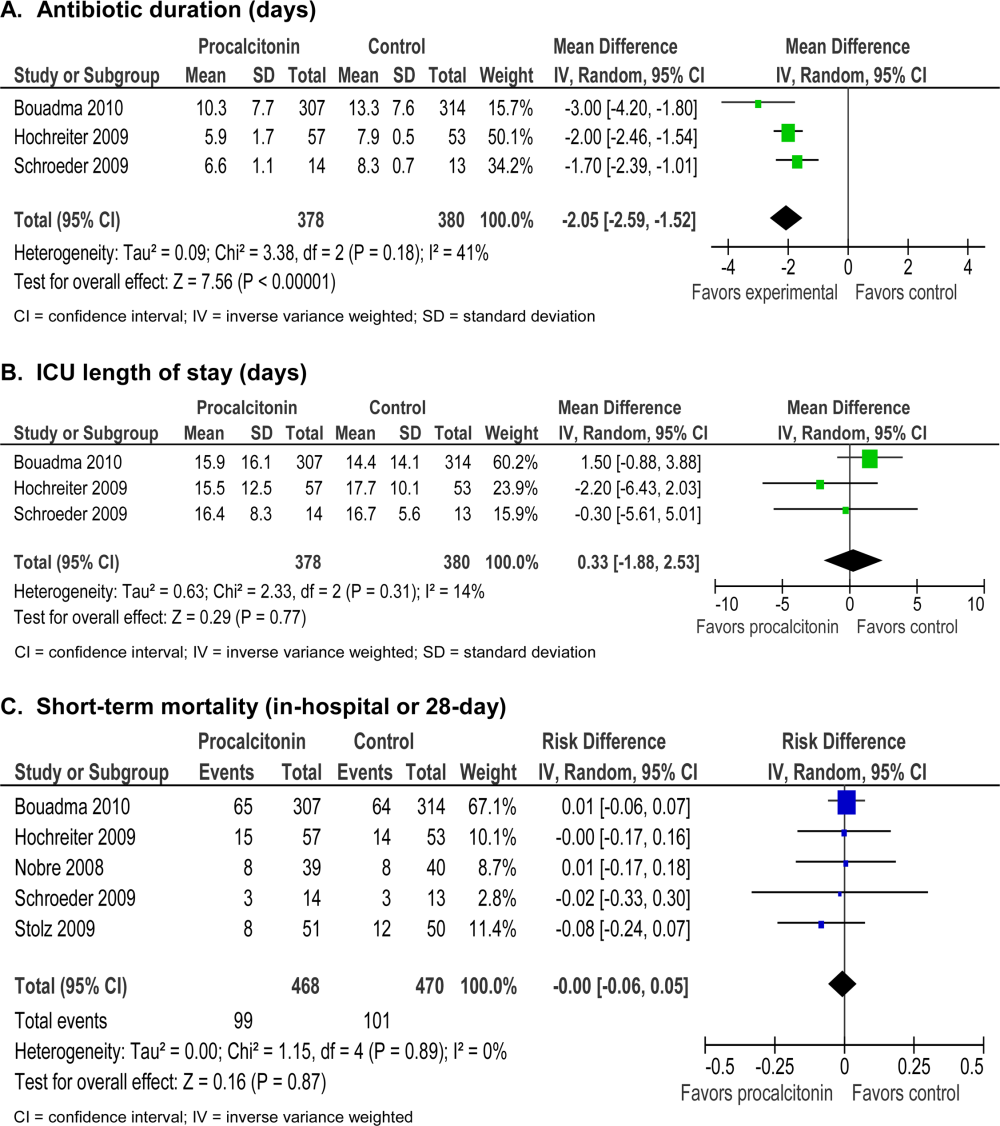

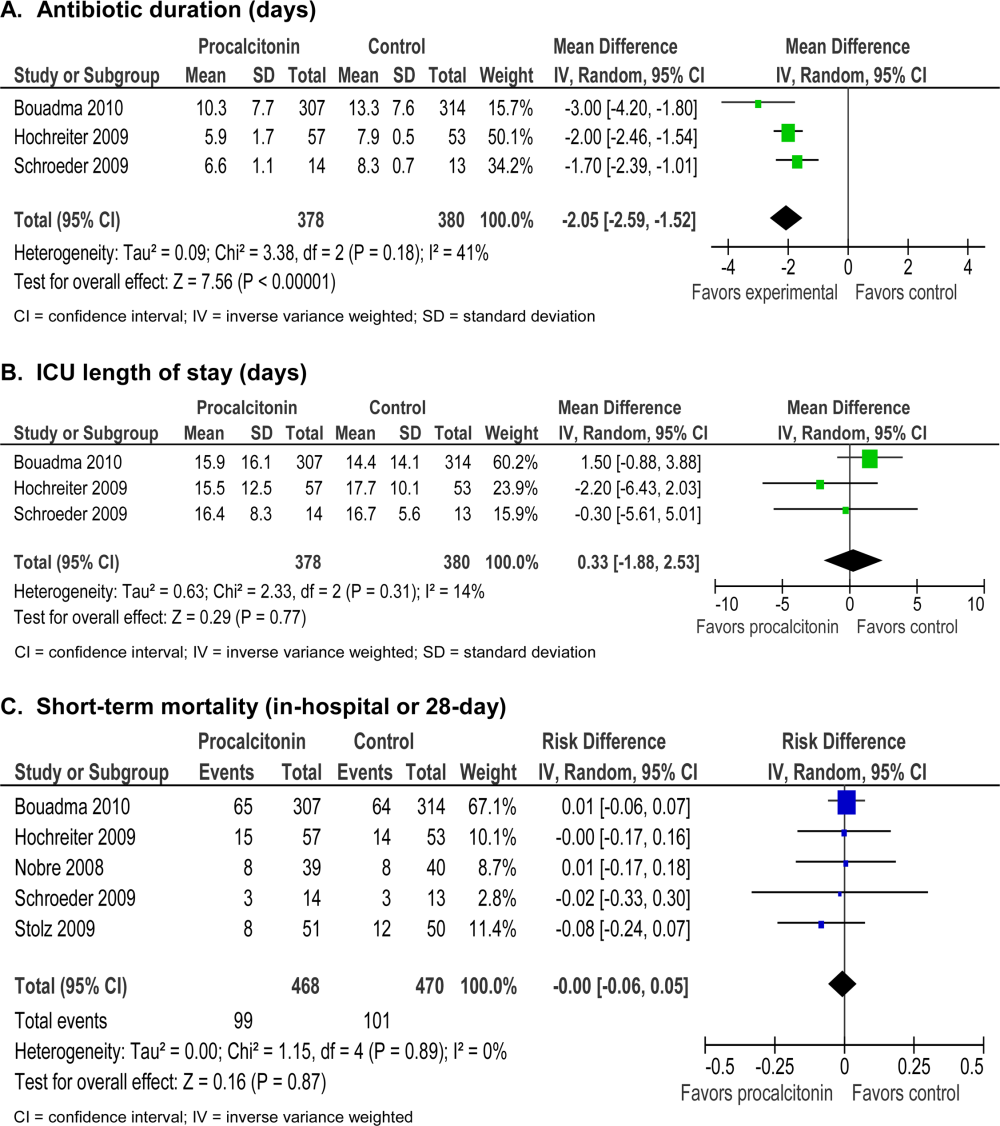

The absolute reduction in duration of antibiotic usage with procalcitonin guidance in these studies ranged from 1.7 to 5 days, and the relative reduction ranged from 21% to 38%. Meta‐analysis of antibiotic duration in adult ICU patients was performed (Figure 2A).

Morbidity

Procalcitonin‐guided antibiotic discontinuation did not increase morbidity, including ICU length of stay (LOS). Meta‐analysis of ICU LOS is displayed in Figure 2B. Limited data on adverse antibiotic events were reported (Table 2).

Mortality

There was no increase in mortality as a result of shorter duration of antibiotic therapy. Meta‐analysis of short‐term mortality (28‐day or in‐hospital mortality) showed a mortality difference of 0.43% favoring procalcitonin‐guided therapy, and a 95% confidence interval (CI) of 6% to 5% (Figure 2C).

Adult ICU Patients: Procalcitonin‐Guided Antibiotic Intensification

Two studies[24, 33] (N=1272) addressed procalcitonin‐guided intensification of antibiotic therapy in adult ICU patients. The Jensen et al. study[33] was a large (N=1200), high‐quality study that used a detailed algorithm for broadening antibiotic therapy in patients with elevated procalcitonin. The Jensen et al. study also educated physicians about empiric therapy and intensification of antibiotic therapy. A second study[24] was too small (N=72) and lacked sufficient details to be informative.

Antibiotic Usage

The Jensen et al. study found a 2‐day increase, or 50% relative increase, in the duration of antibiotic therapy and a 7.9% absolute increase (P=0.002) in the number of days on 3 antibiotics with procalcitonin‐guided intensification.

Morbidity

The Jensen et al. study showed a significant 1‐day increase in ICU LOS (P=0.004) and a significant increase in organ dysfunction. Specifically, patients had a highly statistically significant 5% increase in days on mechanical ventilation (P<0.0001) and 5% increase in days with abnormal renal function (P<0.0001).

Mortality

The Jensen et al. study was a superiority trial powered to test a 7.5% decrease in 28‐day mortality, but no significant difference in mortality was observed with procalcitonin‐guided intensification (31.5% vs 32.0, P=0.83).

Adult Patients With Respiratory Tract Infections

Eight studies[25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 34, 35] (N=3492) addressed initiation and/or discontinuation of antibiotics in adult patients with acute upper and lower respiratory tract infections, including community‐acquired pneumonia, acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and acute bronchitis. Settings included primary care clinics, emergency departments, and hospital wards. Physicians in control groups administered antibiotics according to their own standard practices and/or evidence‐based guidelines. All studies encouraged initiation of antibiotics with procalcitonin levels >0.25 ng/mL, and 4 studies strongly encouraged antibiotics with procalcitonin levels >0.5 ng/mL.

Antibiotic Usage

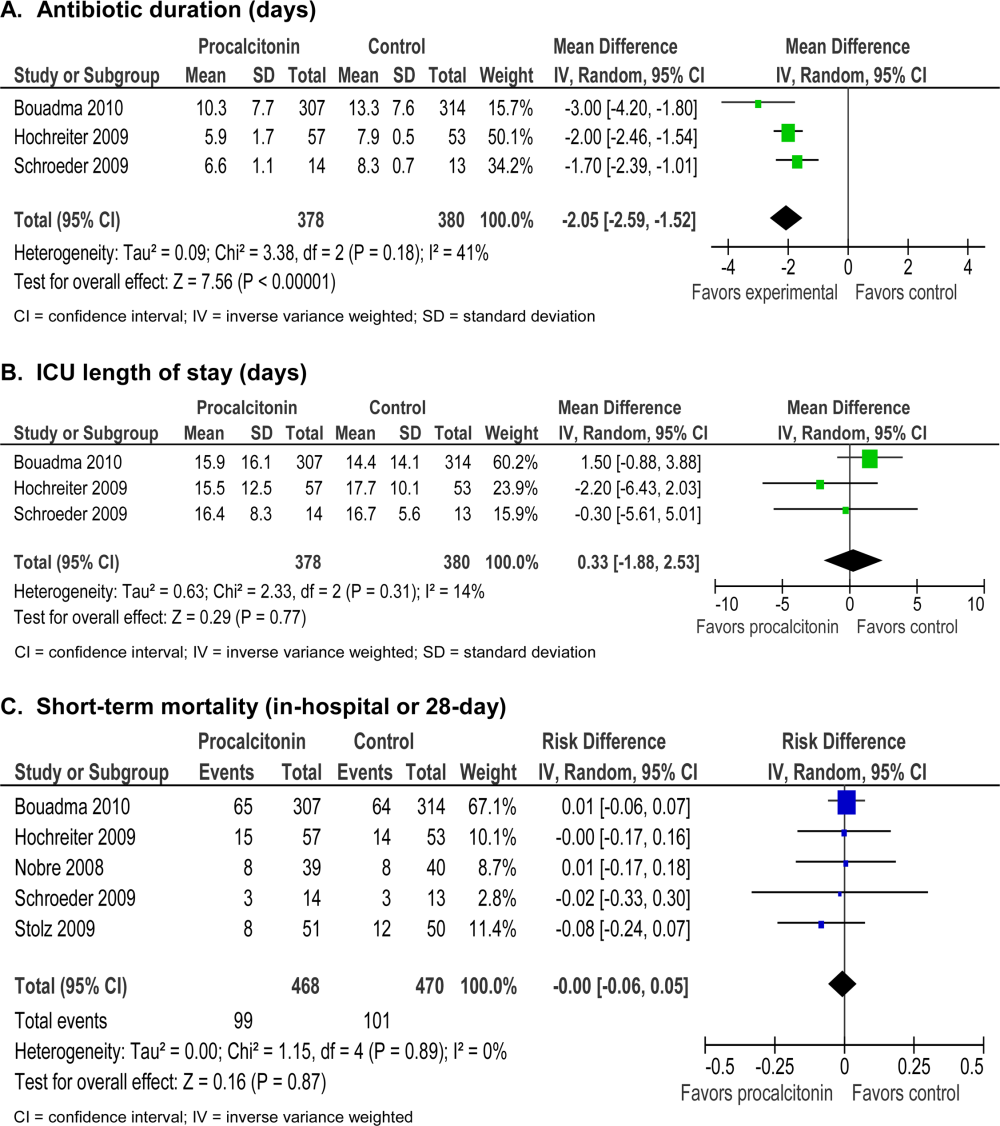

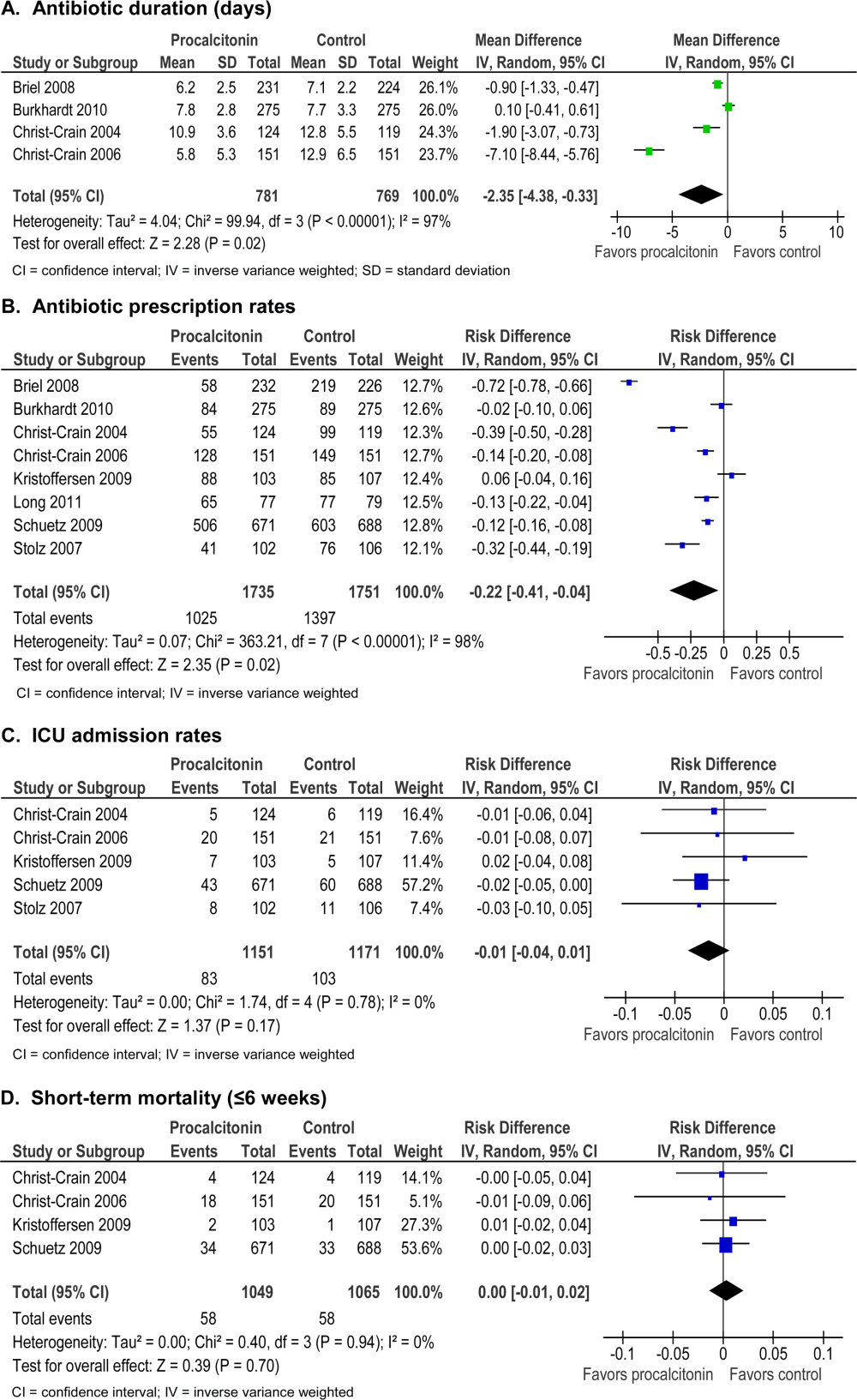

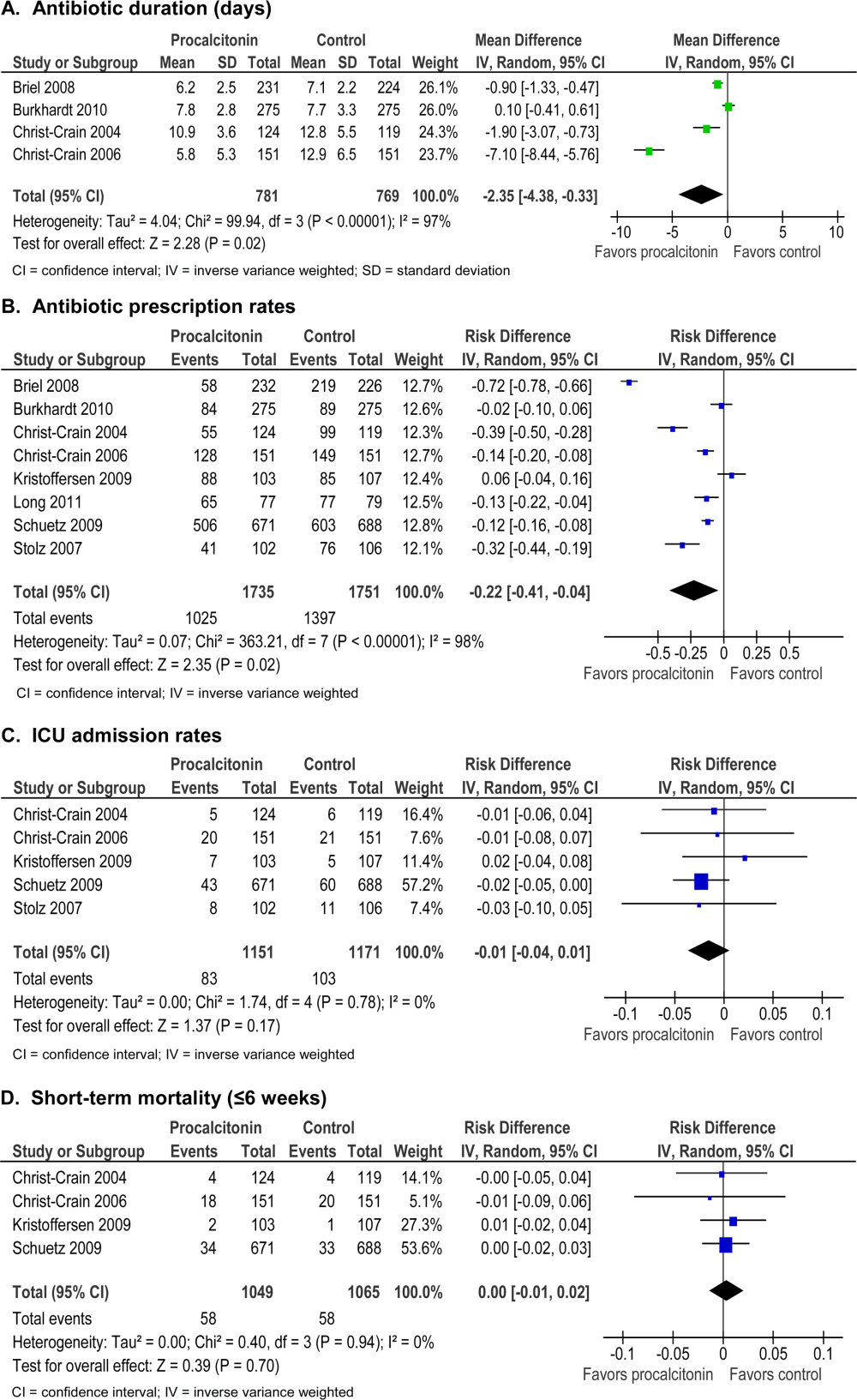

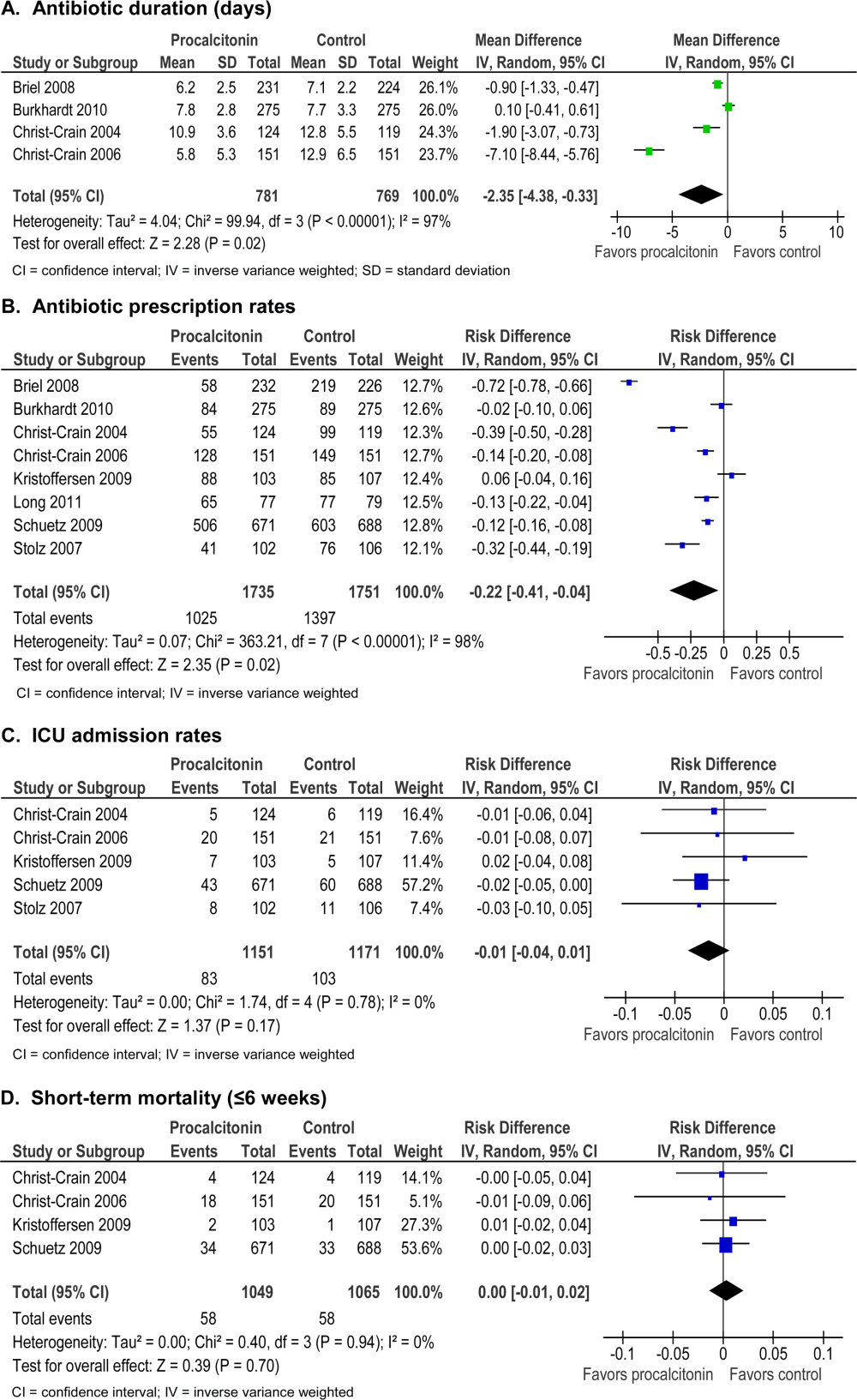

Procalcitonin guidance reduced antibiotic duration, antibiotic prescription rate, and total antibiotic exposure. Absolute reduction in antibiotic duration ranged from 1 to 7 days, and relative reductions ranged from 13% to 55%. Four of the 8 studies reported sufficient details to be pooled into a meta‐analysis (Figure 3A) with a statistically significant pooled mean difference of 2.35 days favoring procalcitonin (95% CI: 4.38 to 0.33). Procalcitonin guidance also reduced antibiotic prescription rate with absolute reductions ranging from 2% to 7% and relative reductions ranging from 1.8% to 72%. Meta‐analysis of prescription rates from 8 studies (Figure 3B) yielded a statistically significant pooled risk difference of 22% (95% CI: 41% to 4%). Total antibiotic exposure was consistently reduced in the 4 studies reporting this outcome.

Morbidity

Procalcitonin guidance did not increase hospital LOS or ICU admission rates. Meta‐analysis of ICU admission rates from 5 studies (Figure 3C) produced a risk difference of 1%, with a narrow 95% CI (4% to 1%). There was insufficient evidence to judge the effect on days of restricted activity or antibiotic adverse events.

Mortality

Procalcitonin guidance did not increase mortality, and meta‐analysis of 4 studies (Figure 3D) produced a risk difference of 0.3% with a narrow 95% CI (1% to 2%), with no statistical heterogeneity (I2=0%).

Neonates With Sepsis

One study[31] (N=121) evaluated procalcitonin‐guided antibiotic therapy for suspected neonatal sepsis. Neonatal sepsis was suspected on the basis of risk factors and clinical signs and symptoms. Antibiotic initiation or discontinuation was based on a procalcitonin nomogram. Antibiotic therapy in the control group was based on the physician's assessment. The quality of this study was rated good, and strength of evidence was rated moderate for antibiotic usage and insufficient for morbidity and mortality outcomes.

Antibiotic Usage

Duration of antibiotic therapy was decreased by 22.4 hours (P=0.012), a 24% relative reduction, and the proportion of neonates on antibiotics 72 hours was reduced by 27% (P=0.002). The largest reduction in antibiotic duration was seen in the 80% to 85% of neonates who were categorized as having possible or infection or unlikely to have infection.

Morbidity

A statistically insignificant 7% reduction in rate of recurrence of infection was seen with procalcitonin‐guided antibiotic therapy (P=0.45).

Mortality

No in‐hospital deaths occurred in either the procalcitonin or control group.

Children Ages 1 to 36 Months With Fever of Unknown Source

One study[36] (N=384) evaluated procalcitonin‐guided antibiotic therapy for fever of unknown source in children 1 to 36 months of age, but the overall strength of evidence was judged insufficient to draw conclusions.

Antibiotic Usage

A statistically insignificant reduction of 3.1% in antibiotic prescription rate was seen with procalcitonin‐guided antibiotic therapy (P=0.49).

Morbidity

Rate of hospitalization was relatively low, and no significant difference was seen between procalcitonin and control groups.

Mortality

In‐hospital mortality was reported as 0% in both arms.

Adult Postoperative Patients at Risk of Infection

One study[32] (N =250) monitored procalcitonin in consecutive patients after colorectal surgery to identify patients at risk of infection who might benefit from prophylactic antibiotic therapy. Two hundred thirty patients had normal procalcitonin levels. Twenty patients with elevated procalcitonin levels (>1.5 ng/mL) were randomized to receive prophylactic antibiotic therapy with ceftriaxone or no antibiotics. The strength of evidence was judged insufficient to draw conclusions from this study.

Antibiotic Usage

Duration of antibiotic therapy was reduced by 3.5% but was not statistically insignificant (P=0.27).

Morbidity

Procalcitonin guidance reduced the incidence of sepsis/systemic inflammatory response syndrome by 60% (p=0.007). The incidences of local and systemic infection were reduced with procalcitonin guidance but were not statistically significant (10%, P=0.53; and 40%, P=0.07, respectively).

Mortality

Mortality was 20% higher in the control arm but was not statistically significant (P=0.07).

DISCUSSION

Summary of the Main Findings

Diagnosis of sepsis or other serious infections in critically ill patients is challenging because clinical criteria for diagnosis overlap with noninfectious causes of the systemic inflammatory response syndrome. Initiation of antibiotic therapy for presumed sepsis is necessary while diagnostic evaluation is ongoing, because delaying antibiotic therapy is associated with increased mortality.[37, 38, 39] Our review found that procalcitonin guidance significantly reduced antibiotic usage in adult ICU patients by reducing the duration of antibiotic therapy, rather than decreasing the initiation of antibiotics, without increasing morbidity or mortality.

In contrast, the use of procalcitonin as an indicator of need for intensification of antibiotic therapy in adult ICU patients should be discouraged because this approach was associated with increased morbidity. The large, well‐designed study by Jensen[33] showed that antibiotic intensification in response to elevated procalcitonin measurement was associated with increased morbidity: a longer ICU LOS, an increase in days on mechanical ventilation, and an increase in days with abnormal renal function. The authors concluded that the increased morbidity could only be explained by clinical harms of increased exposure to broad‐spectrum antibiotics.

Clinical and microbiological evaluations are neither sensitive nor specific for differentiating bacterial from viral respiratory tract infections. Procalcitonin can guide initiation of antibiotic therapy in adults with suspected bacterial respiratory tract infection. Our review showed that procalcitonin guidance significantly reduced antibiotic usage with respect to antibiotic prescription rate, duration of antibiotic therapy, and total exposure to antibiotic therapy in adult patients with respiratory tract infections.

The role of procalcitonin‐guided therapy in other populations is less clear. One study in postoperative colorectal surgery patients reported that elevated procalcitonin levels may identify patients at risk for infection who benefit from prophylactic antibiotic therapy.[32] Patients with elevated procalcitonin levels who received prophylactic antibiotic therapy had a significant decrease in the incidence and severity of systemic infections, whereas patients with normal procalcitonin levels did not require any additional surgical or medical therapy. Although these findings are promising, more data in postoperative patients are needed.

The utility of procalcitonin in pediatric settings is a significant gap in the present literature. One study[31] in neonates with suspected sepsis showed a significant decrease in the proportion of neonates started on empiric antibiotic therapy and a decrease in the duration of antibiotic therapy with procalcitonin guidance. However, there was insufficient evidence that procalcitonin guidance does not increase morbidity or mortality.

Comparison to Other Systematic Reviews

Six systematic reviews of procalcitonin guidance in the management of patients with infections were published prior to our review.[9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14] Our systematic review differs from past reviews in the number of studies included and the pooling of studies according to patient population, type and severity of infection, and different uses of procalcitonin measurements, either for initiation, discontinuation, or intensification of antibiotic therapy. Previous systematic reviews included 7 to 14 studies, whereas ours included 18 randomized, controlled trials. One previous review[13] included and pooled the Jensen et al. study[33] with other studies of adult ICU patients. We evaluated the Jensen et al. study separately because it uniquely looked at procalcitonin‐guided antibiotic intensification in adult ICU patients, in contrast to other studies that looked at procalcitonin‐guided antibiotic discontinuation. We addressed pediatric populations separately from adult patients, and recognizing that there are distinct groups within the pediatric population, we separately grouped neonates and children ages 1 to 36 months. Despite these differences, our review and other systematic reviews, we came to similar conclusions: procalcitonin‐guided antibiotic decision making compared to clinical criteria‐guided antibiotic decision making reduces antibiotic usage without increasing morbidity or mortality.

Limitations

An important limitation of this review was the uncertainty about the noninferiority margin for morbidity and mortality in adult ICU patients. Only the Bouadma et al. study[23] did a power analysis and predefined a margin for noninferiority for 28‐ and 60‐day mortality. Meta‐analysis of all 5 ICU studies showed a pooled point estimate of 0.43% in mortality and a 95% CI of 6% to 5% for difference in mortality between procalcitonin‐guided therapy versus standard care. A 10% noninferiority margin for mortality has been recommended by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and American College of Chest Physicians, but there is concern that a 10% margin for mortality may be too high. Presently, 2 large trials are in progress that may yield more precise estimates of mortality in the future.

Differences in reporting of total antibiotic exposure and morbidity outcomes limited our ability to pool data. Total antibiotic exposure is conventionally reported as mean days per 1000 days of follow‐up, but some studies only reported relative or absolute differences. Likewise, morbidity was reported with different severity of illness scales, including Sepsis‐Related Organ Failure Assessment, Simplified Acute Physiology (SAP) II, SAP III, and Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II, which limited comparisons across studies.

Research Gaps

We identified gaps in the available literature and opportunities for future research. First, the safety and efficacy of procalcitonin‐guided antibiotic therapy needs to be studied in patient populations excluded from current randomized controlled studies, such as immunocompromised patients and pregnant women. Patients who are immunocompromised or have chronic conditions, such as cystic fibrosis, account for a significant percentage of community‐acquired respiratory tract infections and are often treated empirically.[29, 30] Second, standardized reporting of antibiotic adverse events and emergence of antibiotic resistance is needed. Strategies to reduce antibiotic usage have been associated with reductions in antibiotic adverse events, such as Clostridium difficile colitis and superinfection with multi‐drug resistant Gram‐negative bacteria.[37, 40, 41] Few studies in our review reported allergic reactions or adverse events of antibiotic therapy, [25, 27, 34] and only 1 reported antibiotic resistance.[19] Third, procalcitonin guidance should be compared to other strategies to reduce antibiotic usage, such as structured implementation of practice guidelines and antibiotic stewardship programs.[42] One single‐arm study describes how procalcitonin can be used in antibiotic stewardship programs to decrease the duration of antibiotic therapy,[43] but additional studies are needed. Finally, generalizing results from those studies that were conducted primarily in Europe would depend on similar use of and adherence to study‐based algorithms. Newer observational studies have demonstrated reduced antibiotic usage with implementation of procalcitonin algorithms in real‐life settings in Europe, but algorithm adherence was significantly less in the United States.[44, 45]

In summary, our systematic review found that procalcitonin‐guided antibiotic therapy can significantly reduce antibiotic usage in adult ICU patients without affecting morbidity or mortality. Procalcitonin should not be used to guide intensification of antibiotic therapy in adult ICU patients because this approach may increase morbidity. In adults with respiratory infections, procalcitonin guidance can significantly reduce antibiotic usage without adversely affecting morbidity or mortality. There is insufficient evidence to recommend procalcitonin‐guided antibiotic therapy in neonates with sepsis, children with fever of unknown source, or postoperative patients at risk for infection.

Acknowledgments

Disclosures: This project was funded under contract HHSA 2902007‐10058 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), US Department of Health and Human Services. The authors of this article are responsible for its content, including any clinical treatment recommendations. No statement in this article should be construed as an official position of AHRQ or of the US Department of Health and Human Services. There are no conflicts of interest reported by any of the authors.

- , . Sepsis biomarkers: a review. Crit Care. 2010;14(1):R15.

- , . Biomarkers of sepsis. Crit Care Med. 2009;37(7):2290–2298.

- , , . Kinetics of procalcitonin in iatrogenic sepsis. Intensive Care Med. 1998;24(8):888–889.

- , , , et al. Procalcitonin increase after endotoxin injection in normal subjects. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1994;79(6):1605–1608.

- , , , et al. Procalcitonin kinetics as a prognostic marker of ventilator‐associated pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171(1):48–53.

- , , , , . Serum procalcitonin and C‐reactive protein levels as markers of bacterial infection: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39(2):206–217.

- , . Biomarkers in respiratory tract infections: diagnostic guides to antibiotic prescription, prognostic markers and mediators. Eur Respir J. 2007;30(3):556–573.

- , , , et al. Reliability of procalcitonin concentrations for the diagnosis of sepsis in critically ill neonates. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;26(3):664–672.

- , , , , . Effect of procalcitonin‐guided treatment in patients with infections: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Infection. 2009;37(6):497–507.

- , . Procalcitonin to guide duration of antimicrobial therapy in intensive care units: a systematic review. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53(4):379–387.

- , , , , . Procalcitonin‐guided algorithms of antibiotic therapy in the intensive care unit: a systematic review and meta‐analysis of randomized controlled trials. Crit Care Med. 2010;38(11):2229–2241.

- , , , . Procalcitonin algorithms for antibiotic therapy decisions: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials and recommendations for clinical algorithms. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(15):1322–1331.

- , , , , , . An ESCIM systematic review and meta‐analysis of procalcitonin‐guided antibiotic therapy algorithms in adult critically ill patients. Intensive Care Med. 2012;38:940–949.

- , , , et al. Procalcitonin to initiate or discontinue antibiotics in acute respiratory tract infections. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;(9):CD007498.

- , , , , , . Prepared by the Blue Cross and Blue Shield Association Technology Evaluation Center Evidence‐based Practice Center under contract no. 290–2007‐10058‐I. Procalcitonin‐guided antibiotic therapy. Comparative effectiveness review No. 78. AHRQ publication no. 12(13)‐EHC124‐EF. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Available at: www.effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/reports/final.cfm. Published Accessed October 2012.

- Methods Guide for Effectiveness and Comparative Effectiveness Reviews. AHRQ publication no. 10(11)‐EHC063‐EF. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2011.

- , , , et al. Current methods of the US Preventive Services Task Force: a review of the process. Am J Prev Med. 2001;20(3 suppl):21–35.

- , , , et al. AHRQ series paper 5: grading the strength of a body of evidence when comparing medical interventions—agency for healthcare research and quality and the effective health‐care program. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63(5):513–523.

- , , , , . Use of procalcitonin to shorten antibiotic treatment duration in septic patients: a randomized trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;177(5):498–505.

- , , , et al. Procalcitonin (PCT)‐guided algorithm reduces length of antibiotic treatment in surgical intensive care patients with severe sepsis: results of a prospective randomized study. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2009;394(2):221–226.

- , , , et al. Procalcitonin for reduced antibiotic exposure in ventilator‐associated pneumonia: a randomised study. Eur Respir J. 2009;34(6):1364–1375.

- , , , et al. Procalcitonin to guide duration of antibiotic therapy in intensive care patients: a randomized prospective controlled trial. Crit Care. 2009;13(3):R83.

- , , , et al. Use of procalcitonin to reduce patients' exposure to antibiotics in intensive care units (PRORATA trial): a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2010;375(9713):463–474.

- , , , , . Can procalcitonin help us in timing of re‐intervention in septic patients after multiple trauma or major surgery? Hepatogastroenterology. 2007;54(74):359–363.

- , , , et al. Effect of procalcitonin‐based guidelines vs. standard guidelines on antibiotic use in lower respiratory tract infections: the ProHOSP randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2009;302(10):1059–1066.

- , , , et al. Antibiotic treatment interruption of suspected lower respiratory tract infections based on a single procalcitonin measurement at hospital admission—a randomized trial. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2009;15(5):481–487.

- , , , et al. Procalcitonin‐guided antibiotic use vs a standard approach for acute respiratory tract infections in primary care. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(18):2000–2007; discussion 2007–2008.

- , , , et al. Antibiotic treatment of exacerbations of COPD: a randomized, controlled trial comparing procalcitonin‐guidance with standard therapy. Chest. 2007;131(1):9–19.

- , , , et al. Procalcitonin guidance of antibiotic therapy in community‐acquired pneumonia: a randomized trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;174(1):84–93.

- , , , et al. Effect of procalcitonin‐guided treatment on antibiotic use and outcome in lower respiratory tract infections: cluster‐randomised, single‐blinded intervention trial. Lancet. 2004;363(9409):600–607.

- , , , , . Use of procalcitonin‐guided decision‐making to shorten antibiotic therapy in suspected neonatal early‐onset sepsis: prospective randomized intervention trial. Neonatology. 2010;97(2):165–174.

- , , , , , . Pre‐emptive antibiotic treatment vs “standard” treatment in patients with elevated serum procalcitonin levels after elective colorectal surgery: a prospective randomised pilot study. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2006;391(3):187–194.

- , , , et al. Procalcitonin‐guided interventions against infections to increase early appropriate antibiotics and improve survival in the intensive care unit: a randomized trial. Crit Care Med. 2011;39(9):2048–2058.

- , , , et al. Procalcitonin guidance and reduction of antibiotic use in acute respiratory tract infection. Eur Respir J. 2010;36(3):601–607.

- , , , , , . Procalcitonin guidance for reduction of antibiotic use in low‐risk outpatients with community‐acquired pneumonia. Respirology. 2011;16(5):819–824.

- , , , , , . Impact of procalcitonin on the management of children aged 1 to 36 months presenting with fever without source: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Emerg Med. 2010;28(6):647–653.

- , , , , , . Experience with a clinical guideline for the treatment of ventilator‐associated pneumonia. Crit Care Med. 2001;29(6):1109–1115.

- , , , et al. Diagnostic value of procalcitonin, interleukin‐6, and interleukin‐8 in critically ill patients admitted with suspected sepsis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164(3):396–402.

- , , , . Inadequate antimicrobial treatment of infections: a risk factor for hospital mortality among critically ill patients. Chest. 1999;115(2):462–474.

- , , , , . Favorable impact of a multidisciplinary antibiotic management program conducted during 7 years. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2003;24(9):699–706.

- , , , et al. Comparison of 8 vs 15 days of antibiotic therapy for ventilator‐associated pneumonia in adults: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2003;290(19):2588–2598.

- , , , et al. Infectious Diseases Society of America and the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America guidelines for developing an institutional program to enhance antimicrobial stewardship. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44(2):159–177.

- , , , , . Use of procalcitonin (PCT) to guide discontinuation of antibiotic use in an unspecified sepsis is an antimicrobial stewardship program (ASP). Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2011;30(7):853–855.

- , , , et al. Effectiveness and safety of procalcitonin‐guided antibiotic therapy in lower respiratory tract infections in “real life.” Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(9):715–722.

- , , , et al. Effectiveness of a procalcitonin algorithm to guide antibiotic therapy in respiratory tract infections outside of study conditions: a post‐study survey. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2012;29(3):269–277.

Many serum biomarkers have been identified in recent years with a wide range of potential applications, including diagnosis of local and systemic infections, differentiation of bacterial and fungal infections from viral syndromes or noninfectious conditions, prognostic stratification of patients, and enhanced management of antibiotic therapy. Currently, there are at least 178 serum biomarkers that have potential roles to guide antibiotic therapy, and among these, procalcitonin has been the most extensively studied biomarker.[1, 2]

Procalcitonin is the prohormone precursor of calcitonin that is expressed primarily in C cells of the thyroid gland. Conversion of procalcitonin to calcitonin is inhibited by various cytokines and bacterial endotoxins. Procalcitonin's primary diagnostic utility is thought to be in establishing the presence of bacterial infections, because serum procalcitonin levels rise and fall rapidly in bacterial infections.[3, 4, 5] In healthy individuals, procalcitonin levels are very low. In systemic infections, including sepsis, procalcitonin levels are generally greater than 0.5 to 2 ng/mL, but often reach levels 10 ng/mL, which correlates with severity of illness and a poor prognosis. In patients with respiratory tract infections, procalcitonin levels are less elevated, and a cutoff of 0.25 ng/mL seems to be most predictive of a bacterial respiratory tract infection requiring antibiotic therapy.[6, 7, 8] Procalcitonin levels decrease to <0.25 ng/mL as infection resolves, and a decline in procalcitonin level may guide decisions about discontinuation of antibiotic therapy.[5]

The purpose of this systematic review was to synthesize comparative studies examining the use of procalcitonin to guide antibiotic therapy in patients with suspected local or systemic infections in different patient populations. We are aware of 6 previously published systematic reviews evaluating the utility of procalcitonin guidance in the management of infections.[9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14] Our systematic review included more studies and pooled patients into the most clinically similar groups compared to other systematic reviews.

METHODS

This review is based on a comparative effectiveness review prepared for the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality's Effective Health Care Program.[15] A standard protocol consistent with the Methods Guide for Effectiveness and Comparative Effectiveness Reviews[16] was followed. A detailed description of the methods is available online (

Study Question

In selected populations of patients with suspected local or systemic infection, what are the effects of using procalcitonin measurement plus clinical criteria for infection to guide initiation, intensification, and/or discontinuation of antibiotic therapy when compared to clinical criteria for infection alone?

Search Strategy

MEDLINE and EMBASE were searched from January 1, 1990 through December 16, 2011, and the Cochrane Controlled Trials register was searched with no date restriction for randomized and nonrandomized comparative studies using the following search terms: procalcitonin AND chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; COPD; critical illness; critically ill; febrile neutropenia; ICU; intensive care; intensive care unit; postoperative complication(s); postoperative infection(s); postsurgical infection(s); sepsis; septic; surgical wound infection; systemic inflammatory response syndrome OR postoperative infection. In addition, a search for systematic reviews was conducted in MEDLINE, the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, and Web sites of the National Institute for Clinical Excellence, the National Guideline Clearinghouse, and the Health Technology Assessment Programme. Gray literature, including databases with regulatory information, clinical trial registries, abstracts and conference papers, grants and federally funded research, and manufacturing information was searched from January 1, 2006 to June 28, 2011.

Study Selection

A single reviewer screened abstracts and selected studies looking at procalcitonin‐guided antibiotic therapy. Second and third reviewers were consulted to screen articles when needed. Studies were included if they fulfilled all of the following criteria: (1) randomized, controlled trial or nonrandomized comparative study; (2) adult and/or pediatric patients with known or suspected local or systemic infection, including critically ill patients with sepsis syndrome or ventilator‐associated pneumonia, adults with respiratory tract infections, neonates with sepsis, children with fever of unknown source, and postoperative patients at risk of infection; (3) interventions included initiation, intensification, and/or discontinuation of antibiotic therapy guided by procalcitonin plus clinical criteria; (4) primary outcomes included antibiotic usage (antibiotic prescription rate, total antibiotic exposure, duration of antibiotic therapy, and days without antibiotic therapy); and (5) secondary outcomes included morbidity (antibiotic adverse events, hospital and/or intensive care unit length of stay), mortality, and quality of life.

Studies with any of the following criteria were excluded: published in non‐English language, not reporting primary data from original research, not a randomized, controlled trial or nonrandomized comparative study, not reporting relevant outcomes.

Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

A single reviewer abstracted data and a second reviewer confirmed accuracy. Disagreements between reviewers were resolved by group discussion among the research team and final quality rating was assigned by consensus adjudication. Data elements were abstracted into the following categories: quality assessment, applicability and clinical diversity assessment, and outcome assessment. Quality of included studies was assessed using the US Preventive Services Task Force framework[17] by at least 2 independent reviewers. Three quality categories were used: good, fair, and poor.

Data Synthesis and Analysis

The decision to incorporate formal data synthesis in this review was made after completing the formal literature search, and the decision to pool studies was based on the specific number of studies with similar questions and outcomes. If a meta‐analysis could be performed, subgroup and sensitivity analyses were based on clinical similarity of available studies and reporting of mean and standard deviation. The pooling method involved inverse variance weighting and a random effects model.

The strength of evidence was graded using the Methods Guide,[16] a system based on the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation Working Group.[18] The following domains were addressed: risk of bias, consistency, directness, and precision. The overall strength of evidence was graded as high, moderate, low, or insufficient. The final strength of evidence grading was made by consensus adjudication among the authors.

RESULTS

Of the 2000 studies identified through the literature search, 1986 were excluded and 14 studies[19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32] were included. Search of gray literature yielded 4 published studies.[33, 34, 35, 36] A total of 18 randomized, controlled trials comparing procalcitonin guidance to use of clinical criteria alone to manage antibiotic therapy in patients with infections were included. The PRISMA diagram (Figure 1) depicts the flow of search screening and study selection. We sought, but did not find, nonrandomized comparative studies of populations, comparisons, interventions, and outcomes that were not adequately studied in randomized, controlled trials.

Data were pooled into clinically similar groups that were reviewed separately: (1) adult intensive care unit (ICU) patients, including patients with ventilator‐associated pneumonia; (2) adult patients with respiratory tract infections; (3) neonates with suspected sepsis; (4) children between 1 to 36 months of age with fever of unknown source; and (5) postoperative patients at risk of infection. Tables summarizing study quality and outcome measures with strength of evidence are available online (

| Outcome | Author, Year | N | PCT‐Guided Therapya | Controla | Difference PCT‐CTRL (95% CI) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||

| Critically ill adult patients: procalcitonin‐guided antibiotic discontinuation | ||||||

| ABT Duration, d | Hochreiter, 2009[22] | 110 | 5.9 | 7.9 | 2.0 (2.5 to 1.5) | <0.001 |

| Nobre, 2008[19] | 79 | 66 | 9.5 (ITT), 10 (PP) | 2.6 (5.5 to 0.3), 3.2 (1.1 to5.4) | 0.15, 0.003 | |

| Schroeder, 2009[20] | 27 | 6.6 | 8.3 | 1.7 (2.4 to 1.0) | <0.001 | |

| Stolz, 2009[21] | 101 | 10 (616)b | 15 (1023)b | 5 | 0.049 | |

| Bouadma, 2010[23] | 621 | 10.3 | 13.3 | 3.0 (4.20 to 1.80) | <0.0001 | |

| Days without ABTs, day 28 | Nobre, 2008[19] | 79 | 15.3, 17.4 | 13, 13.6 | 2.3 (5.9 to 1.8), 3.8 (0.1 to 7.5)c | 0.28, 0.04 |

| Stolz, 2009[21] | 101 | 13 (221)b | 9.5 (1.517)b | 3.5 | 0.049 | |

| Bouadma, 2010[23] | 621 | 14.3 | 11.6 | 2.7 (1.4 to 4.1) | <0.001 | |

| Total ABT exposured | Nobre, 2008[19] | 79 | 541 | 644 | 1.1e (0.9 to 1.3), 1.3e (1.1 to 1,5)c | 0.07, 0.0002 |

| 504 | 655 | |||||

| Stolz, 2009[21] | 101 | 1077 | 1341 | |||

| Bouadma, 2010[23]d | 621 | 653 | 812 | 159 (185 to 131) | <0.001 | |

| Critically ill adult patients: procalcitonin‐guided antibiotic intensification | ||||||

| ABT duration, days | Jensen, 2011[33] | 1200 | 6 (311)b | 4 (310)b | NR | NR |

| Days spent in ICU on 3 ABTs | Jensen, 2011[33] | 1200 | 3570/5447 (65.5%) | 2721/4717 (57.7%) | 7.9% (6.0 to 9.7) | 0.002 |

| Adult patients with respiratory tract infections | ||||||

| ABT duration, da | Schuetz, 2009[2][5] | 1359 | 5.7 | 8.7 | 3.0 | |

| Christ‐Crain, 2004[30] | 243 | 10.9 | 12.8 | 1.9 (3.1 to 0.7) | 0.002 | |

| Kristoffersen, 2009[26] | 210 | 5.1 | 6.8 | 1.7 | ||

| Briel, 2008[27] | 458 | 6.2 | 7.1 | 1.0 (1.7 to 0.4) | <0.05 | |

| Long, 20113[5] | 162 | 5 (36)f | 7 (59)f | 2.0 | <0.001 | |

| Burkhardt, 2010[34] | 550 | 7.8 | 7.7 | 0.1 (0.7 to 0.9) | 0.8 | |

| Christ‐Crain, 2006[29] | 302 | 5.8 | 12.9 | 7.1(8.4 to 5.8) | <0.0001 | |

| Antibiotic prescription rate, % | Schuetz, 2009[2][5] | 1359 | 506/671 (75.4%) | 603/688 (87.6%) | 12.2% (16.3 to 8.1) | <0.05 |

| Christ‐Crain, 2004[30] | 243 | 55/124 (44.4%) | 99/119 (83.2%) | 38.8% (49.9 to 27.8) | <0.0001 | |

| Kristoffersen, 2009[26] | 210 | 88/103 (85.4%) | 85/107 (79.4%) | 6.0% (4.3 to 16.2) | 0.25 | |

| Briel, 2008[27] | 458 | 58/232 (25.0%) | 219/226 (96.9%) | 72% (78 to 66) | <0.05 | |

| Long, 20113[5] | 162 | NR (84.4%) | NR (97.5%) | 13.1% | 0.004 | |

| Stolz, 2007[28] | 208 | 41/102 (40.2%) | 76/106 (71.7%) | 31.5% (44.3 to 18.7) | <0.0001 | |

| Christ‐Crain, 2006[29] | 302 | 128/151 (84.8%) | 149/151 (98.79%) | 13.9% (19.9 to 7.9) | <0.0001 | |

| Burkhardt, 2010[34] | 550 | 84/275 (30.5%) | 89/275 (32.4%) | 1.8% (9.6 to 5.9) | 0.701 | |

| Total ABT exposure | Stolz, 2007[28] | 208 | NR | NR | 31.5% (18.7 to 44.3) | <0.0001 |

| Long, 20113[5] | 162 | NR | NR | NR | ||

| Christ‐Crain, 2006[29] | 302 | 136g | 323g | |||

| Christ‐Crain, 2004[30] | 243 | 332g | 661g | |||

| Neonates with sepsis | ||||||

| ABTs 72 hours, % | Stocker, 2010[31] | All neonates (N=121) | 33/60 (55%) | 50/61 (82%) | 27.0 (42.8 to 11.1) | 0.002 |

| Infection proven/probably (N=21) | 9/9 (100%) | 12/12 (100%) | 0% (0 to 0) | NA | ||

| Infection possible (N=40) | 13/21 (61.9%) | 19/19 (100%) | 38.1 (58.9 to 17.3) | 0.003 | ||

| Infection unlikely (N=60) | 11/30 (36.7%) | 19/30 (63.3%) | 26.6 (51.1 to 2.3) | 0.038 | ||

| ABT duration, h | Stocker, 2010[31] | All neonates (N=121) | 79.1 | 101.5 | 22.4 | 0.012 |

| Infection proven/probably (N=21) | 177.8 | 170.8 | 7 | NSS | ||

| Infection possible (N=40) | 83.4 | 111.5 | 28.1 | <0.001 | ||

| Infection unlikely (N=60) | 46.5 | 67.4 | 20.9 | 0.001 | ||

| Children ages 136 months with fever of unknown source | ||||||

| Antibiotic prescription rate, % | Manzano, 2010[36] | All children (N=384) | 48/192 (25%) | 54/192 (28.0%) | 3.1 (12.0 to 5.7) | 0.49 |

| No SBI or neutropenia (N=312) | 14/158 (9%) | 16/154 (10%) | 1.5 (8.1 to 5.0) | 0.65 | ||

| Adult postoperative patients at risk of infection | ||||||

| ABT duration, d | Chromik, 2006[32] | All patients (N=20) | 5.5 | 9 | 3.5 | 0.27 |

| Outcome | Author, Year | N | PCTa | Controla | Difference, PCT‐CTRL (95% CI) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||

| Critically ill adult patients: procalcitonin‐guided antibiotic discontinuation | ||||||

| ICU LOS, days | Hochreiter, 2009[22] | 110 | 15.5 | 17.7 | 2.2 | 0.046 |

| Nobre, 2008[19] | 79 | 4 | 7 | 4.6 (8.2 to 1.0) | 0.02 | |

| Schroeder, 2009[20] | 27 | 16.4 | 16.7 | 0.3 (5.6 to 5.0) | NSS | |

| Bouadma, 2010[23] | 621 | 15.9 | 14.4 | 1.5 (0.9 to 3.1) | 0.23 | |

| Hospital LOS, days | Nobre, 2008[19] | 79 | 17 | 23.5 | 2.5 (6.5 to 1.5) | 0.85 |

| Stolz, 2009[21] | 101 | 26 (721)b | 26 (16.822.3)b | 0 | 0.15 | |

| Bouadma, 2010[23] | 621 | 26.1 | 26.4 | 0.3 (3.2 to 2.7) | 0.87 | |

| ICU‐free days alive, 128 | Stolz, 2009[21] | 101 | 10 (018)b | 8.5 (018)c | 1.5 | 0.53 |

| SOFA day 28 | Bouadma, 2010[23] | 621 | 1.5 | 0.9 | 0.6 (0.0, 1.1) | 0.037 |

| SOFA score max | Schroeder, 2009[20] | 27 | 7.3 | 8.3 | 8.1 (4.1 to 1.7) | NSS |

| SAPS II score | Hochreiter, 2009[22] | 110 | 40.1 | 40.5 | 0.4 (6.4 to 5.6) | >0.05 |

| Days without MV | Stolz, 2009[21] | 101 | 21 (224)b | 19 (8.522.5)b | 2.0 | 0.46 |

| Bouadma, 2010[23] | 621 | 16.2 | 16.9 | 0.7 (2.4 to 1.1) | 0.47 | |

| Critically ill adult patients: procalcitonin‐guided antibiotic intensification | ||||||

| ICU LOS, da | Svoboda, 2007[24] | 72 | 16.1 | 19.4 | 3.3 (7.0 to 0.4) | 0.09 |

| Jensen, 2011[33] | 1200 | 6 (312)b | 5 (311)b | 1 | 0.004 | |

| SOFA scorea | Svoboda, 2007[24] | 72 | 7.9 | 9.3 | 1.4 (2.8 to 0.0) | 0.06 |

| Days on MVa | Svoboda, 2007[24] | 72 | 10.3 | 13.9 | 3.6 (7.6 to 0.4) | 0.08 |

| Jensen, 2011[33] | 1200 | 3569 (65.5%) | 2861 (60.7%) | 4.9% (3 to 6.7) | <0.0001 | |

| Percent days in ICU with GFR <60 | Jensen, 2011[33] | 1200 | 2796 (51.3%) | 2187 (46.4%) | 5.0 % (3.0 to 6.9) | <0.0001 |

| Adult patients with respiratory tract infections | ||||||

| Hospital LOS, da | Schuetz, 2009[2][5] | 1359 | 9.4 | 9.2 | 0.2 | |

| Christ‐Crain, 2004[30] | 224 | 10.78.9 | 11.210.6 | 0.5 (3.0 to 2.0) | 0.69 | |

| Kristoffersen, 2009[26] | 210 | 5.9 | 6.7 | 0.8 | 0.22 | |

| Stolz, 2007[28] | 208 | 9 (115)b | 10 (115)b | 1 | 0.96 | |

| Christ‐Crain, 2006[29] | 302 | 12.09.1 | 13.09.0 | 1 (3.0 to 1.0) | 0.34 | |

| ICU admission, % | Schuetz, 2009[2][5] | 1359 | 43/671 (6.4%) | 60/688 (8.7%) | 2.3% (5.2 to 0.4) | 0.12 |

| Christ‐Crain, 2004[30] | 224 | 5/124 (4.0%) | 6/119 (5.0%) | 1.0% (6.2 to 4.2) | 0.71 | |

| Kristoffersen, 2009[26] | 210 | 7/103 (6.8%) | 5/107 (4.7%) | 2.1% (4.2 to 8.4) | 0.51 | |

| Stolz, 2007[28] | 208 | 8/102 (7.8%) | 11/106 (10.4%) | 2.5% (10.3 to 5.3) | 0.53 | |

| Christ‐Crain, 2006[29] | 302 | 20/151 (13.2%) | 21/151 (13.94%) | 0.7% (8.4 to 7.1) | 0.87 | |

| Antibiotic adverse events | Schuetz, 2009[2][5]c | 1359 | 133/671 (19.8%) | 193/688 (28.1%) | 8.2% (12.7 to 3.7) | |

| Briel, 2008[27]d | 458 | 2.34.6 days | 3.66.1 days | 1.1 days (2.1 to 0.1) | <0.05 | |

| Burkhardt, 2010[34]e | 550 | 11 /59 (18.6%) | 16/101 (15.8%) | 2.8% (9.4 to 15.0) | 0.65 | |

| Restricted activity, df | Briel, 2008[27] | 458 | 8.73.9 | 8.63.9 | 0.2 (0.4 to 0.9) | >0.05 |

| Burkhardt, 2010[34] | 550 | 9.1 | 8.8 | 0.25 (0.52 to 1.03) | >0.05 | |

| Neonates with sepsis | ||||||

| Recurrence of infection | Stocker, 2010[31] | 121 | 32% | 39% | 7 | 0.45 |

| Children ages 136 months with fever of unknown source | ||||||

| Hospitalization rate | Manzano, 2010[36] | All children (N=384) | 50/192 (26%) | 48/192 (25%) | 1 (8 to 10) | 0.81 |

| No SBI or neutropenia (N=312) | 16/158 (10%) | 11/154 (7%) | 3 (3 to 10) | 0.34 | ||

| Adult postoperative patients at risk of infection | ||||||

| Hospital LOS, days | Chromik, 2006[32] | 20 | 18 | 30 | 12 | 0.057 |

| Local wound infection, % | Chromik, 2006[32] | 20 | 1/10 | 2/10 | 10 (41.0 to 21.0) | 0.53 |

| Systemic infection, % | Chromik, 2006[32] | 20 | 3/10 | 7/10 | 40.0 (80.2 to 0.2) | 0.07 |

| Sepsis/SIRS, % | Chromik, 2006[32] | 20 | 2/10 | 8/10 | 60.0 (95.1 to 24.9) | 0.007 |

| Mortality | Mortality | Difference | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | Author, Year | N | PCT‐Guided Therapy | Control | PCT‐CTRL (95% CI) | P Value |

| ||||||

| Critically ill adult patients: procalcitonin‐guided antibiotic discontinuation | ||||||

| 28‐day mortality | Nobre, 2008[19] | 79 | 8/39 (20.5%) | 8/40 (20.0%) | 0.5 (17.2 to 18.2), | 0.95 |

| 5/31 (16.1%) | 6/37 (16.2%) | 0.1 (17.7 to 17.5)a | 0.99 | |||

| Stolz, 2009[21] | 101 | 8/51 (15.7%) | 12/50 (24.0%) | 8.3 (23.8 to 7.2) | 0.29 | |

| Bouadma, 2010[23] | 621 | 65/307 (21.2%) | 64/314 (20.4%) | 0.8 (5.6 to 7.2) | 0.81 | |

| 60‐day mortality | Bouadma, 2010[23] | 621 | 92/307 (30.0%) | 82/314 (26.1%) | 3.9 (3.2 to 10.9) | 0.29 |

| In‐hospital mortality | Nobre, 2008[19] | 79 | 9/39 (23.1%) | 9/40 (22.5%) | 0.6 (17.9 to 19.1) | 0.95 |

| 6/31 (19.4%) | 7/37 (18.9%) | 0.4+ (18.3 to 19.2) | 0.96 | |||

| Stolz, 2009[21] | 101 | 10/51 (19.6%) | 14/50 (28.0%) | 8.4, (24.9 to 8.1) | 0.32 | |

| Hochreiter, 2009[22] | 110 | 15/57 (26.3%) | 14/53 (26.4%) | 0.1, (16.6 to 16.4) | 0.99 | |

| Schroeder, 2009[20] | 27 | 3/14 (21.4%) | 3/13 (23.1%) | 1.7, (33.1 to 29.8) | 0.92 | |

| Critically ill adult patients: procalcitonin‐guided antibiotic intensification | ||||||

| 28‐day mortality | Svoboda, 2007[24] | 72 | 10/38 (26.3%) | 13/34 (38.2%) | 11.9 (33.4 to 9.6) | 0.28 |

| 28‐day mortality | Jensen, 2011[33] | 1200 | 190/604 (31.5%) | 191/596 (32.0%) | 0.6 (4.7 to 5.9) | 0.83 |

| Adult patients with respiratory tract infections | ||||||

| 6‐month mortality | Stolz, 2007[28] | 208 | 5/102 (4.9%) | 9/106 (8.5%) | 3.6% (10.3 to 3.2%) | 0.30 |

| 6‐week mortality | Christ‐Crain, 2006[29] | 302 | 18/151 (11.9%) | 20/151 (13.2%) | 1.3% (8.8 to 6.2) | 0.73 |

| 28‐day mortality | Christ‐Crain, 2004[30] | 243 | 4/124(3.2%) | 4/119 (3.4%) | 0.1% (4.6 to 4.4) | 0.95 |

| Schuetz, 2009 (30‐day)[25] | 1359 | 34/671(5.1%) | 33/688(4.8%) | 0.3% (2.1 to 2.5) | 0.82 | |

| Briel, 2008[27] | 458 | 0/231(0%) | 1/224 (0.4%) | 0.4% (1.3 to 0.4) | 0.31 | |

| Burkhardt, 2010[34] | 550 | 0/275(0%) | 0/275 (0%) | 0 | ||

| Kristoffersen, 2009[26] | 210 | 2/103(1.9%) | 1/107 (0.9%) | 1.0% (2.2 to 4.2) | 0.54 | |

| Long, 20113[5] | 162 | 0/81 (0%) | 0/81 (0%) | 0 | ||

| Neonates with sepsis | ||||||

| Mortality (in‐hospital) | Stocker, 2010[31] | 121 | 0% | 0% | 0 (0 to 0) | NA |

| Children ages 136 months with fever of unknown source | ||||||

| Mortality | Manzano, 2010[36] | 384 | All children | 0% | 0% | 0 (0 to 0) |

| Adult postoperative patients at risk of infection | ||||||

| Mortality | Chromik, 2006[32] | 20 | 1/10 (10%) | 3/10 (30%) | 20 (54.0 to 14.0) | 0.07 |

Adult ICU Patients: Procalcitonin‐Guided Antibiotic Discontinuation

Five studies[19, 20, 21, 22, 23] (N=938) addressed procalcitonin‐guided discontinuation of antibiotic therapy in adult ICU patients. Four studies conducted superiority analyses for mortality with procalcitonin‐guided therapy, whereas 1 study conducted a noninferiority analysis. Absolute procalcitonin values for discontinuation of antibiotics ranged from 0.25 to 1 ng/mL. Physicians in control groups administered antibiotics according to their standard practice.

Antibiotic Usage

The absolute reduction in duration of antibiotic usage with procalcitonin guidance in these studies ranged from 1.7 to 5 days, and the relative reduction ranged from 21% to 38%. Meta‐analysis of antibiotic duration in adult ICU patients was performed (Figure 2A).

Morbidity

Procalcitonin‐guided antibiotic discontinuation did not increase morbidity, including ICU length of stay (LOS). Meta‐analysis of ICU LOS is displayed in Figure 2B. Limited data on adverse antibiotic events were reported (Table 2).

Mortality

There was no increase in mortality as a result of shorter duration of antibiotic therapy. Meta‐analysis of short‐term mortality (28‐day or in‐hospital mortality) showed a mortality difference of 0.43% favoring procalcitonin‐guided therapy, and a 95% confidence interval (CI) of 6% to 5% (Figure 2C).

Adult ICU Patients: Procalcitonin‐Guided Antibiotic Intensification

Two studies[24, 33] (N=1272) addressed procalcitonin‐guided intensification of antibiotic therapy in adult ICU patients. The Jensen et al. study[33] was a large (N=1200), high‐quality study that used a detailed algorithm for broadening antibiotic therapy in patients with elevated procalcitonin. The Jensen et al. study also educated physicians about empiric therapy and intensification of antibiotic therapy. A second study[24] was too small (N=72) and lacked sufficient details to be informative.

Antibiotic Usage

The Jensen et al. study found a 2‐day increase, or 50% relative increase, in the duration of antibiotic therapy and a 7.9% absolute increase (P=0.002) in the number of days on 3 antibiotics with procalcitonin‐guided intensification.

Morbidity

The Jensen et al. study showed a significant 1‐day increase in ICU LOS (P=0.004) and a significant increase in organ dysfunction. Specifically, patients had a highly statistically significant 5% increase in days on mechanical ventilation (P<0.0001) and 5% increase in days with abnormal renal function (P<0.0001).

Mortality

The Jensen et al. study was a superiority trial powered to test a 7.5% decrease in 28‐day mortality, but no significant difference in mortality was observed with procalcitonin‐guided intensification (31.5% vs 32.0, P=0.83).

Adult Patients With Respiratory Tract Infections

Eight studies[25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 34, 35] (N=3492) addressed initiation and/or discontinuation of antibiotics in adult patients with acute upper and lower respiratory tract infections, including community‐acquired pneumonia, acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and acute bronchitis. Settings included primary care clinics, emergency departments, and hospital wards. Physicians in control groups administered antibiotics according to their own standard practices and/or evidence‐based guidelines. All studies encouraged initiation of antibiotics with procalcitonin levels >0.25 ng/mL, and 4 studies strongly encouraged antibiotics with procalcitonin levels >0.5 ng/mL.

Antibiotic Usage

Procalcitonin guidance reduced antibiotic duration, antibiotic prescription rate, and total antibiotic exposure. Absolute reduction in antibiotic duration ranged from 1 to 7 days, and relative reductions ranged from 13% to 55%. Four of the 8 studies reported sufficient details to be pooled into a meta‐analysis (Figure 3A) with a statistically significant pooled mean difference of 2.35 days favoring procalcitonin (95% CI: 4.38 to 0.33). Procalcitonin guidance also reduced antibiotic prescription rate with absolute reductions ranging from 2% to 7% and relative reductions ranging from 1.8% to 72%. Meta‐analysis of prescription rates from 8 studies (Figure 3B) yielded a statistically significant pooled risk difference of 22% (95% CI: 41% to 4%). Total antibiotic exposure was consistently reduced in the 4 studies reporting this outcome.

Morbidity

Procalcitonin guidance did not increase hospital LOS or ICU admission rates. Meta‐analysis of ICU admission rates from 5 studies (Figure 3C) produced a risk difference of 1%, with a narrow 95% CI (4% to 1%). There was insufficient evidence to judge the effect on days of restricted activity or antibiotic adverse events.

Mortality

Procalcitonin guidance did not increase mortality, and meta‐analysis of 4 studies (Figure 3D) produced a risk difference of 0.3% with a narrow 95% CI (1% to 2%), with no statistical heterogeneity (I2=0%).

Neonates With Sepsis

One study[31] (N=121) evaluated procalcitonin‐guided antibiotic therapy for suspected neonatal sepsis. Neonatal sepsis was suspected on the basis of risk factors and clinical signs and symptoms. Antibiotic initiation or discontinuation was based on a procalcitonin nomogram. Antibiotic therapy in the control group was based on the physician's assessment. The quality of this study was rated good, and strength of evidence was rated moderate for antibiotic usage and insufficient for morbidity and mortality outcomes.

Antibiotic Usage

Duration of antibiotic therapy was decreased by 22.4 hours (P=0.012), a 24% relative reduction, and the proportion of neonates on antibiotics 72 hours was reduced by 27% (P=0.002). The largest reduction in antibiotic duration was seen in the 80% to 85% of neonates who were categorized as having possible or infection or unlikely to have infection.

Morbidity

A statistically insignificant 7% reduction in rate of recurrence of infection was seen with procalcitonin‐guided antibiotic therapy (P=0.45).

Mortality

No in‐hospital deaths occurred in either the procalcitonin or control group.

Children Ages 1 to 36 Months With Fever of Unknown Source

One study[36] (N=384) evaluated procalcitonin‐guided antibiotic therapy for fever of unknown source in children 1 to 36 months of age, but the overall strength of evidence was judged insufficient to draw conclusions.

Antibiotic Usage

A statistically insignificant reduction of 3.1% in antibiotic prescription rate was seen with procalcitonin‐guided antibiotic therapy (P=0.49).

Morbidity

Rate of hospitalization was relatively low, and no significant difference was seen between procalcitonin and control groups.

Mortality

In‐hospital mortality was reported as 0% in both arms.

Adult Postoperative Patients at Risk of Infection

One study[32] (N =250) monitored procalcitonin in consecutive patients after colorectal surgery to identify patients at risk of infection who might benefit from prophylactic antibiotic therapy. Two hundred thirty patients had normal procalcitonin levels. Twenty patients with elevated procalcitonin levels (>1.5 ng/mL) were randomized to receive prophylactic antibiotic therapy with ceftriaxone or no antibiotics. The strength of evidence was judged insufficient to draw conclusions from this study.

Antibiotic Usage

Duration of antibiotic therapy was reduced by 3.5% but was not statistically insignificant (P=0.27).

Morbidity

Procalcitonin guidance reduced the incidence of sepsis/systemic inflammatory response syndrome by 60% (p=0.007). The incidences of local and systemic infection were reduced with procalcitonin guidance but were not statistically significant (10%, P=0.53; and 40%, P=0.07, respectively).

Mortality

Mortality was 20% higher in the control arm but was not statistically significant (P=0.07).

DISCUSSION

Summary of the Main Findings

Diagnosis of sepsis or other serious infections in critically ill patients is challenging because clinical criteria for diagnosis overlap with noninfectious causes of the systemic inflammatory response syndrome. Initiation of antibiotic therapy for presumed sepsis is necessary while diagnostic evaluation is ongoing, because delaying antibiotic therapy is associated with increased mortality.[37, 38, 39] Our review found that procalcitonin guidance significantly reduced antibiotic usage in adult ICU patients by reducing the duration of antibiotic therapy, rather than decreasing the initiation of antibiotics, without increasing morbidity or mortality.

In contrast, the use of procalcitonin as an indicator of need for intensification of antibiotic therapy in adult ICU patients should be discouraged because this approach was associated with increased morbidity. The large, well‐designed study by Jensen[33] showed that antibiotic intensification in response to elevated procalcitonin measurement was associated with increased morbidity: a longer ICU LOS, an increase in days on mechanical ventilation, and an increase in days with abnormal renal function. The authors concluded that the increased morbidity could only be explained by clinical harms of increased exposure to broad‐spectrum antibiotics.

Clinical and microbiological evaluations are neither sensitive nor specific for differentiating bacterial from viral respiratory tract infections. Procalcitonin can guide initiation of antibiotic therapy in adults with suspected bacterial respiratory tract infection. Our review showed that procalcitonin guidance significantly reduced antibiotic usage with respect to antibiotic prescription rate, duration of antibiotic therapy, and total exposure to antibiotic therapy in adult patients with respiratory tract infections.

The role of procalcitonin‐guided therapy in other populations is less clear. One study in postoperative colorectal surgery patients reported that elevated procalcitonin levels may identify patients at risk for infection who benefit from prophylactic antibiotic therapy.[32] Patients with elevated procalcitonin levels who received prophylactic antibiotic therapy had a significant decrease in the incidence and severity of systemic infections, whereas patients with normal procalcitonin levels did not require any additional surgical or medical therapy. Although these findings are promising, more data in postoperative patients are needed.

The utility of procalcitonin in pediatric settings is a significant gap in the present literature. One study[31] in neonates with suspected sepsis showed a significant decrease in the proportion of neonates started on empiric antibiotic therapy and a decrease in the duration of antibiotic therapy with procalcitonin guidance. However, there was insufficient evidence that procalcitonin guidance does not increase morbidity or mortality.

Comparison to Other Systematic Reviews

Six systematic reviews of procalcitonin guidance in the management of patients with infections were published prior to our review.[9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14] Our systematic review differs from past reviews in the number of studies included and the pooling of studies according to patient population, type and severity of infection, and different uses of procalcitonin measurements, either for initiation, discontinuation, or intensification of antibiotic therapy. Previous systematic reviews included 7 to 14 studies, whereas ours included 18 randomized, controlled trials. One previous review[13] included and pooled the Jensen et al. study[33] with other studies of adult ICU patients. We evaluated the Jensen et al. study separately because it uniquely looked at procalcitonin‐guided antibiotic intensification in adult ICU patients, in contrast to other studies that looked at procalcitonin‐guided antibiotic discontinuation. We addressed pediatric populations separately from adult patients, and recognizing that there are distinct groups within the pediatric population, we separately grouped neonates and children ages 1 to 36 months. Despite these differences, our review and other systematic reviews, we came to similar conclusions: procalcitonin‐guided antibiotic decision making compared to clinical criteria‐guided antibiotic decision making reduces antibiotic usage without increasing morbidity or mortality.

Limitations

An important limitation of this review was the uncertainty about the noninferiority margin for morbidity and mortality in adult ICU patients. Only the Bouadma et al. study[23] did a power analysis and predefined a margin for noninferiority for 28‐ and 60‐day mortality. Meta‐analysis of all 5 ICU studies showed a pooled point estimate of 0.43% in mortality and a 95% CI of 6% to 5% for difference in mortality between procalcitonin‐guided therapy versus standard care. A 10% noninferiority margin for mortality has been recommended by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and American College of Chest Physicians, but there is concern that a 10% margin for mortality may be too high. Presently, 2 large trials are in progress that may yield more precise estimates of mortality in the future.

Differences in reporting of total antibiotic exposure and morbidity outcomes limited our ability to pool data. Total antibiotic exposure is conventionally reported as mean days per 1000 days of follow‐up, but some studies only reported relative or absolute differences. Likewise, morbidity was reported with different severity of illness scales, including Sepsis‐Related Organ Failure Assessment, Simplified Acute Physiology (SAP) II, SAP III, and Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II, which limited comparisons across studies.

Research Gaps