User login

Admission to a hospital for acute care is often a puzzling and traumatic experience for patients.[1, 2] Even after overcoming important hurdles such as receiving the right diagnosis, being treated with appropriate therapies, and experiencing initial improvement, the ultimate goal of complete recovery after discharge remains elusive for many. Dozens of interventions have been tested to reduce failed recoveries and readmissions with mixed results. Most of these have relied on system‐level changes such as improved medication reconciliation and postdischarge phone calls.[3, 4] Physicians have largely been ignored in such efforts. Most systems leave it up to individual physicians to decide how much time and effort to invest in postdischarge care, and patient outcomes are often highly dependent on a physician's skill, interest, and experience.

We are both hospitalists who attend regularly on general internal medicine services in the United States and Canada. In that capacity, we have experienced many successes and failures in helping patients recover after discharge. This Perspective frames the problem of engaging both hospitalists and office‐based physicians in transitions of care within the current context of readmission reduction efforts, and proposes a more structured approach for integrating those physicians into postdischarge care to promote recovery. Although we also consider broader policy efforts to reduce fragmentation and misaligned incentives such as electronic health records (EHRs), accountable care organizations (ACOs), and the patient‐centered medical home (PCMH), our focus is on how these may (or may not) help front‐line physicians to solve the puzzle of posthospital recovery in the current state of affairs.

THE PROBLEMLACK OF TIME, VARIABLE ENGAGEMENT, SILOED COMMUNICATION

Perhaps the most important barrier to engaging physicians in the posthospital recovery phase is their limited time and energy. Today's rapid throughput and the complexity of acute care leave little bandwidth for issues that are not right in front of hospitalists. Once discharged, patients are often out of sight, out of mind.[5] Office‐based physicians face similar time constraints.[6] In both settings, physicians find themselves operating in silos with significant communication barriers that are time consuming and difficult to overcome.

There are many current policy efforts to break down these silos, a prominent example being recent incentives to speed the widespread use of EHRs. Although EHR implementation progress has been steady, nearly half of US hospitals still do not have a basic EHR, and more advanced functions required for sharing care summaries and allowing patients to access their EHR are not in place at most hospitals that have implemented basic EHRs already.[7] Furthermore, the state of implementation in office‐based settings lags even farther behind hospitals.[8] Finally, our personal experience working in systems with fully integrated EHR systems has suggested to us that sometimes more shared information simply becomes part of the problem, as it is far too easy to include too many complex details of hospitalization in discharge summaries.

Moreover, as front‐line hospitalists, we generally want to help with transitional issues that occur after patients have left our hospital, and we are very mindful of the tradition of the physician who takes responsibility for all aspects of their patients' care in all settings. Yet this tradition may be more representative of the 20th century ideal of continuity than the new continuity that we see emerging in the 21st century.[9] Thus, the question at hand now is how individual physicians should prioritize and execute these tasks without overreaching.

EFFECTS OF THE PROBLEM IN PRACTICEVARIATIONS IN PHYSICIAN ENGAGEMENT

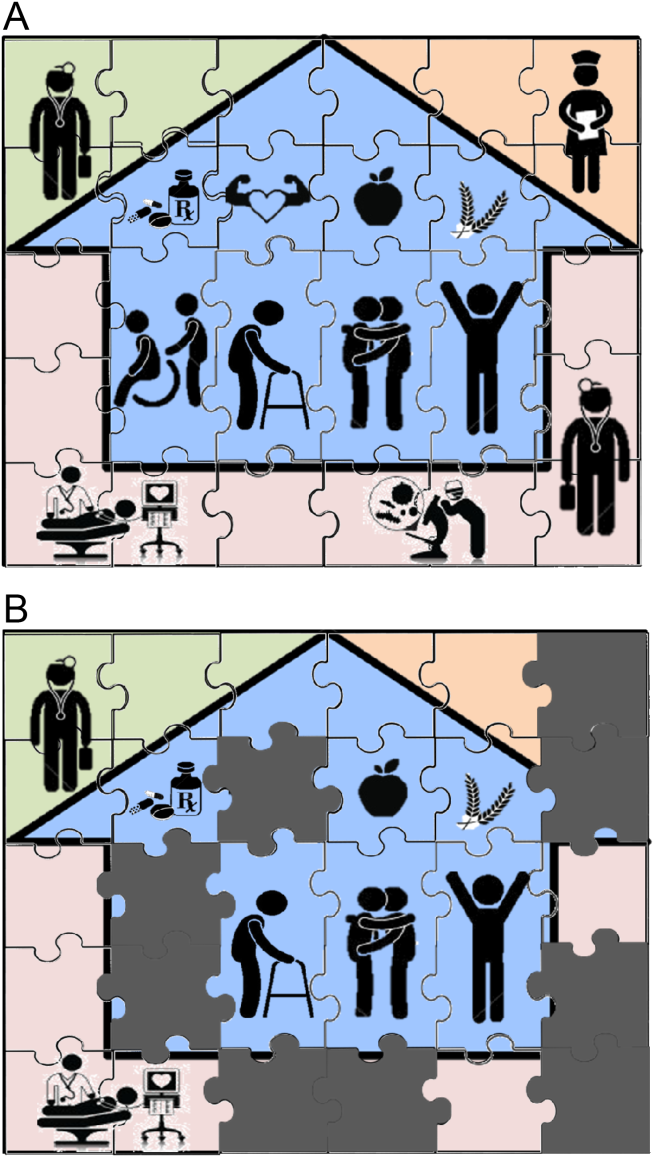

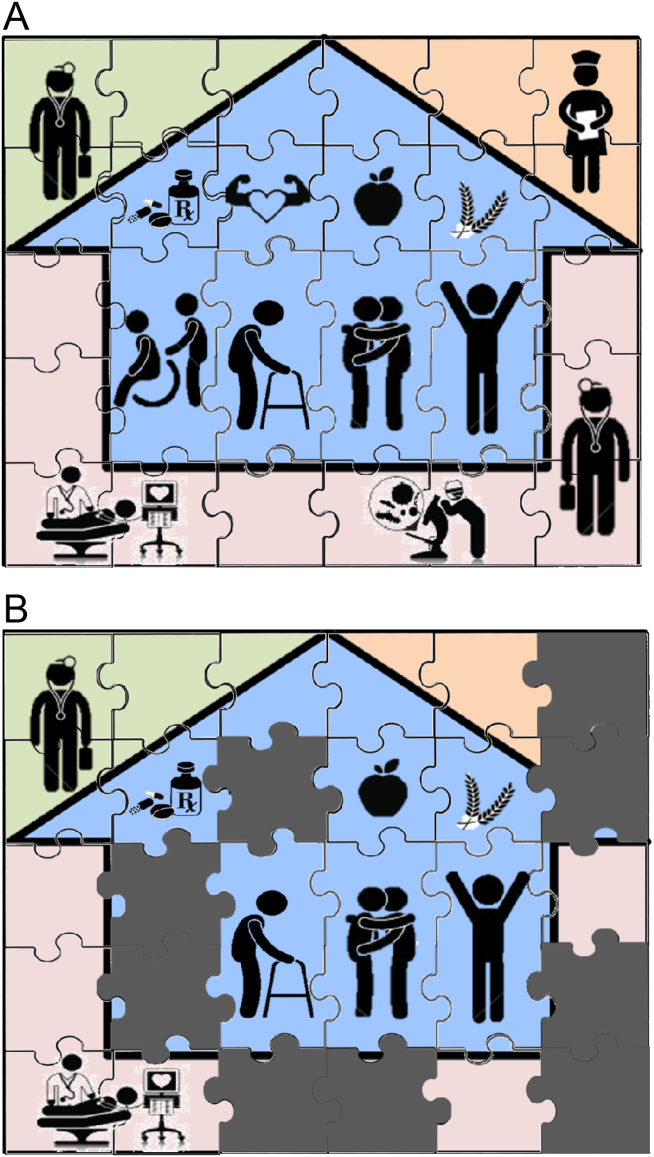

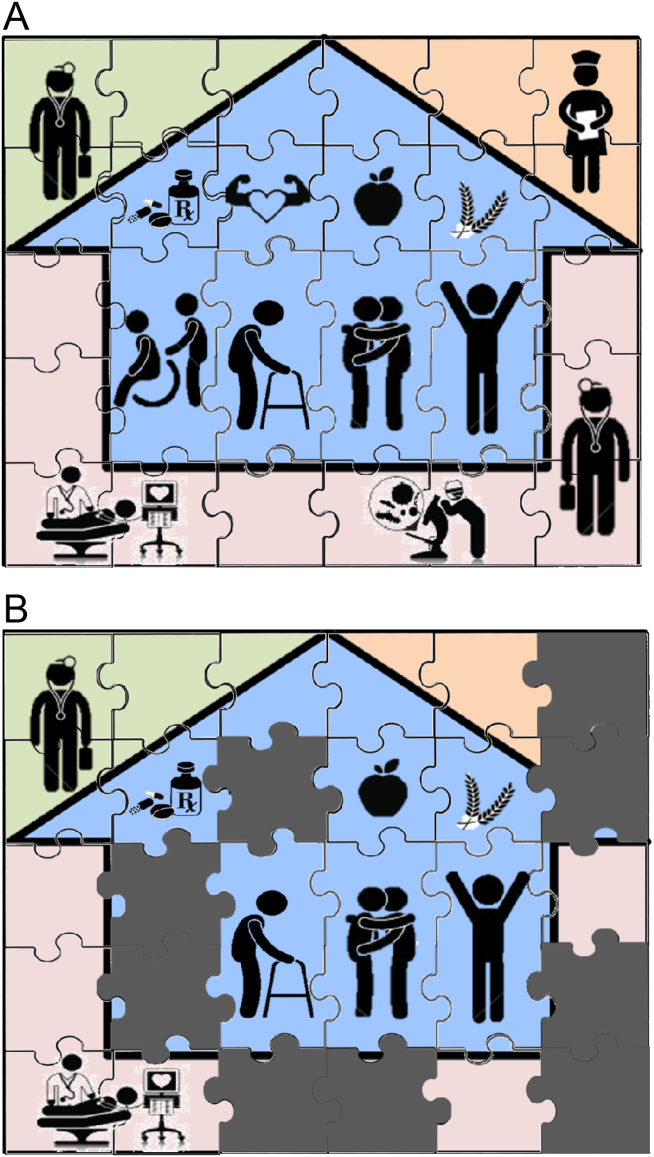

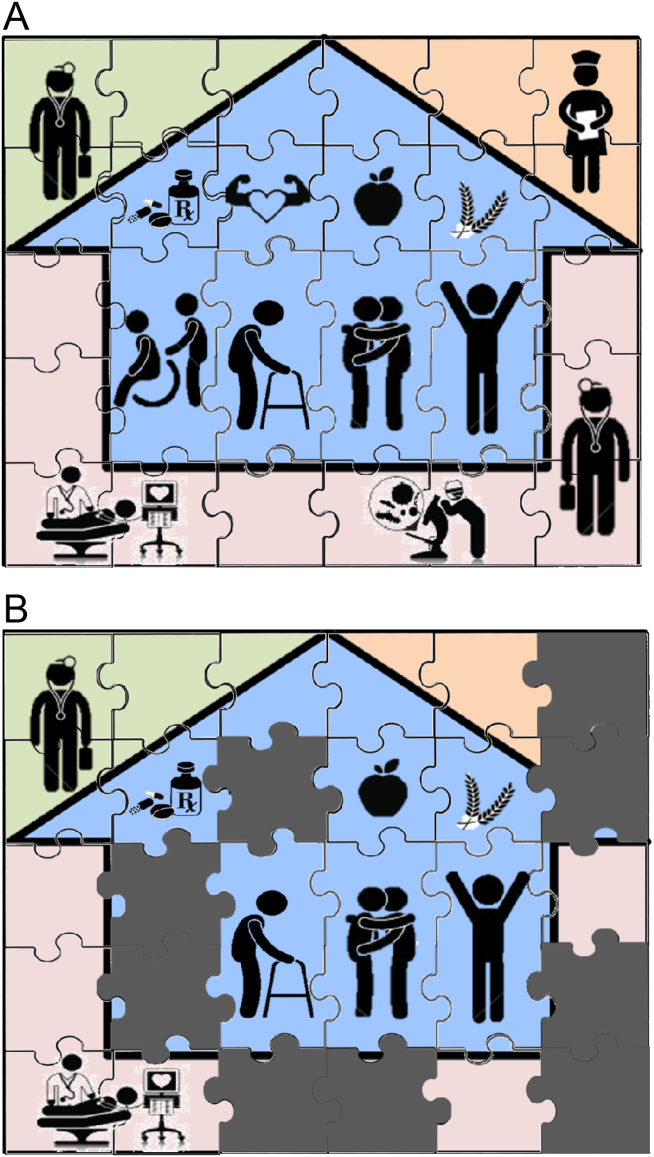

Patient needs after discharge are not uniform, and risk prediction is still imprecise despite many studies.[10] Some patients need no help; others need only targeted help with specific gaps; still others need full‐time navigators to meaningfully reduce their risk of ending up back in the emergency department.[11] The goal is to piece together the resources required to create a complete picture of patient support; much like the way ones solves a jigsaw puzzle (Figure 1A). Despite best efforts, the gaps in careor missing pieces[12]may only become apparent after discharge. Recent research suggests physicians do not see the same gaps as patients do and agree on causes for readmission less than 50% of the time.[13, 14] Often, these gaps come to light when an outside pharmacist, home health nurse, or case manager reaches out to the hospital or primary care physician to address a new problem (Figure 1B). As frequent recipients of those calls for help, we are conflicted in our reaction. On the one hand, we want to know when our carefully crafted plans fall apart. On the other hand, neither of us looks forward to voice mail messages informing us that the specialist to whom we referred the patient for follow‐up never called with an appointment. Micromanaging this kind of care can be very frustrating, both when we are the first person called or resource of last resort.

Even when physicians do not feel burdened by postdischarge care, they may be ineffective due to a lack of experience or resources. These efforts can leave them feeling demoralized, which in turn may further discourage them from future engagement, solidifying a pattern of missing (or perhaps lost) pieces (Figure 1B). Too often, a well‐intentioned but underpowered effort becomes a solution crushed by the weight of the problem. Successful physician models for care coordination must balance competing ideals of the 1 doctor, 1 patient strategy that preserve continuity,[15] with the need to focus individual physicians' time on those postdischarge tasks in which their engagement is clearly needed.

Certain payment models, such as ACOs, may help catalyze specific solutions to these problems by creating incentives for better coordination at the organizational level (eg, hospitals, skilled nursing facilities, and clinics), but these incentives may not necessarily translate into changes in physician practice, particularly as physicians payments are not yet part of bundled hospital care payments.[16] Likewise, innovative practice models such as the PCMH have promise to reshape the way healthcare is delivered, particularly by fortifying the role of primary care providers; but again, we note the lack of specific guidance for providers, particularly hospitalists. The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality defines care coordination as 1 of the 5 pillars of the PCMH, but notes considerable uncertainty about how to operationalize coordination around transitions from hospital care: A clearer understanding of, and research on, the optimal role of the PCMH in terms of leadership and care coordination in inpatient care is needed. Specifically, a better understanding of the possible approaches and the tradeoffs involved with eachin terms of access, quality, cost, and patient experiencewould be useful.[17] Early studies of these outcomes from both ACOs and PCMHs suggest improvements in some areas of patient and provider experience but not in others.[18, 19, 20, 21] Thus, we believe that although EHRs, ACOs, and PCMHs provide laudable and fundamentally necessary organizational changes to spur innovation and quality in transitions, more discussion about the specific roles for physicians is still needed. Though certainly not a definitive or exhaustive list, we provide a few specific suggestions for more effective physician engagement below.

ENABLING STRUCTURESAPPROACHES FOR MORE EFFECTIVE POSTDISCHARGE ENGAGEMENT

One approach for structuring physician participation is to create new roles for physicians as transitionalists,[22] extensivists,[23] or comprehensive‐care physicians[24] to help patients migrate from the volatile postacute period into a more stable state of recovery. Much as hospital‐based rapid response teams add a layer of additional expertise and availability without replacing the role of the attending physician, in this model, transitionalist or extensivist teams could respond to postacute issues in concert with inpatient and outpatient physicians of record.

Another approach could be to integrate the patients' hospitalists or primary care physicians into interprofessional teams modeled after hospital transfer centers, robust interdisciplinary teams that manage intense care‐coordination issues for complex inpatients. A similar approach could be used to elevate care transitions from hospital to homea postdischarge recovery center. In the same way that transfer centers develop ongoing relationships with referring hospitals and communities, postdischarge recovery centers will also need to develop working relationships with community resources like senior centers, transportation services, and the patients' physicians that provide ongoing care to be effective. A recent study of a similar concept (a virtual ward) [25] provides both a framework for this type of interprofessional collaboration and also caution in underestimating the dose or intensity of such interventions needed for those interventions to succeed. In that study, the interprofessional team was not fully integrated into the ecosystem in which patients lived, and providers frequently had difficulty communicating with the patients' ongoing caregivers, including both physicians and personal support workers.

Certainly, there are many other approaches that could be imagined, and there are pros and cons for those suggested here. Although some of these roles may seem like new types of physicians, which could worsen fragmentation, what we are suggesting is more akin to hybridization of current hospitalist and primary care provider roles. A first step could be just giving a name to the additional effort asked of these providers, and paying for time spent when they are not acting in either the inpatient attending or outpatient attending role but in the coordinating role. Fortunately, Medicare's new initiative to pay for chronic‐care management will allow physicians, clinics, and hospitals more flexibility to bill for such services that are not based on face‐to‐face encounters in the hospital or clinic.[26]

Moreover, although solving the puzzle of posthospital recovery cannot be fixed with hospitalist‐centric solutions alone, we believe more discourse is needed to define contributions from these physicians. Current policies, such as the PCMH, focus on the clinic and primary‐care providers, whereas the Medicare Readmission Reduction Program focuses on the hospital but not the hospitalist. Thus, there is a specific gap in engaging hospitalists in ongoing efforts to solve this puzzle and answer important questions about the specific role(s) of the hospitalist[27] as well as the primary care provider[28] in preventing readmissions and facilitating recovery. Certainly, integration of any new roles is needed to avoid fragmentation by default, and our suggestion of roles such as transitionalists or transfer center physicians are intended as examples to facilitate broader discussion about individual physician roles. As is often the case in healthcare, a 1 size fits all solution is unlikely, and a variety of complimentary roles may be needed to accommodate the diversity of patients and providers as well as the delivery systems where they interact.

CONCLUSION

Although the emphasis on interdisciplinary care and systems approaches in promoting recovery is welcome, individual physicians are usually overlooked in these discussions. Most physicians want to help but cannot simply do more in the absence of more creative and structured approaches. As a recent commentary on care transitions suggested, It's the how, not just the what.[29] We agree but would add, It's also about who. Thus, the time has come to engage physicians within care‐delivery models specifically designed to solve this puzzle. Although interprofessional teams are clearly needed, patients look to individuals who know them, not teams, when they run into trouble, and their first move is often to call the doctor. Because physicians play such an important role in the acute phase of illness, their struggles and efforts in the postacute phase need to be recognized and streamlined if we are to improve our patients' chances of full recovery.

Disclosure: Nothing to report.

- . Post‐hospital syndrome‐an acquired transient condition of generalized risk. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:2169–2170.

- , . Reducing the trauma of hospitalization. JAMA. 2014;311(21):2169–2170.

- , , , et al. Hospital‐initiated transitional care interventions as a patient safety strategy: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158:433–440.

- , , , et al. Interventions to reduce 30‐day rehospitalization: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(8):520–528.

- , , , , . “Out of sight, out of mind”: housestaff perceptions of quality‐limiting factors in discharge care at teaching hospitals. J Hosp Med. 2012;7(5):376–381.

- . Instant replay—a quarterback's view of care coordination. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:489–491.

- , , , et al. More than half of US hospitals have at least a basic EHR, but stage 2 criteria remain challenging for most. Health Aff (Millwood). 2014;33(9):1664–1671.

- , , , , , . Despite substantial progress In EHR adoption, health information exchange and patient engagement remain low in office settings. Health Aff (Millwood). 2014;33(9):1672–1679.

- , . Understanding the value of continuity in the 21st century [published online May 18, 2015]. JAMA Intern Med. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.1345.

- , , , et al. Risk prediction models for hospital readmission: a systematic review. JAMA. 2011;306(15):1688–1698.

- , , , , , . Perceptions of readmitted patients on the transition from hospital to home. J Hosp Med. 2012;7(9):709–712.

- , , , et al. “Missing pieces”—functional, social, and environmental barriers to recovery for vulnerable older adults transitioning from hospital to home. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62:1556–1561.

- , , , et al. Readmissions in the era of patient engagement. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(11):1870–1872.

- , , , et al. Challenges faced by patients with low socioeconomic status during the post‐hospital transition. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(2):283–289.

- , . Teaching physicians to care amid chaos. JAMA. 2013;309(10):987–988.

- , . Including physicians in bundled hospital care payments: time to revisit an old idea? JAMA. 2015;313(19):1907–1908.

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Coordinating care for adults with complex care needs in the patient‐centered medical home: challenges and solutions. Available at: http://www.pcmh.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/attachments/Coordinating%20Care%20for%20Adults%20with%20Complex%20Care%20Needs.pdf. Accessed June 8, 2015.

- , , , . Performance differences in year 1 of pioneer accountable care organizations. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(20):1927–1936.

- , , , . Changes in patients' experiences in Medicare Accountable Care Organizations. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(18):1715–1724.

- , , , , . Association between participation in a multipayer medical home intervention and changes in quality, utilization, and costs of care. JAMA. 2014;311(8):815–825.

- , , , et al. Patient‐centered medical home intervention at an internal medicine resident safety‐net clinic. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(18):1694–1701.

- . Walking the walk in transitional care: the “hospitalist” role expands far beyond hospital walls. Today's Hospitalist. Available at: http://www.todayshospitalist.com/index.php?b=articles_read33(5):770–777.

- , , , et al. Effect of a post‐discharge virtual ward on readmission or death for high‐risk patients: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014;312:1305–1312.

- , , . Medicare and care coordination: expanding the clinician's toolbox. JAMA. 2015;313(8):797–798.

- . Hospitalists' responsibility, role in readmission prevention. The Hospitalist. Available at: http://www.the‐hospitalist.org/article/hospitalists‐responsibility‐role‐in‐readmission‐prevention. Published April 3, 2015. Accessed July 7, 2015.

- , . Bridging the hospitalist‐primary care divide through collaborative care. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(4):308–309.

- , . Care transitions: it's the how, not just the what. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(5):539–540.

Admission to a hospital for acute care is often a puzzling and traumatic experience for patients.[1, 2] Even after overcoming important hurdles such as receiving the right diagnosis, being treated with appropriate therapies, and experiencing initial improvement, the ultimate goal of complete recovery after discharge remains elusive for many. Dozens of interventions have been tested to reduce failed recoveries and readmissions with mixed results. Most of these have relied on system‐level changes such as improved medication reconciliation and postdischarge phone calls.[3, 4] Physicians have largely been ignored in such efforts. Most systems leave it up to individual physicians to decide how much time and effort to invest in postdischarge care, and patient outcomes are often highly dependent on a physician's skill, interest, and experience.

We are both hospitalists who attend regularly on general internal medicine services in the United States and Canada. In that capacity, we have experienced many successes and failures in helping patients recover after discharge. This Perspective frames the problem of engaging both hospitalists and office‐based physicians in transitions of care within the current context of readmission reduction efforts, and proposes a more structured approach for integrating those physicians into postdischarge care to promote recovery. Although we also consider broader policy efforts to reduce fragmentation and misaligned incentives such as electronic health records (EHRs), accountable care organizations (ACOs), and the patient‐centered medical home (PCMH), our focus is on how these may (or may not) help front‐line physicians to solve the puzzle of posthospital recovery in the current state of affairs.

THE PROBLEMLACK OF TIME, VARIABLE ENGAGEMENT, SILOED COMMUNICATION

Perhaps the most important barrier to engaging physicians in the posthospital recovery phase is their limited time and energy. Today's rapid throughput and the complexity of acute care leave little bandwidth for issues that are not right in front of hospitalists. Once discharged, patients are often out of sight, out of mind.[5] Office‐based physicians face similar time constraints.[6] In both settings, physicians find themselves operating in silos with significant communication barriers that are time consuming and difficult to overcome.

There are many current policy efforts to break down these silos, a prominent example being recent incentives to speed the widespread use of EHRs. Although EHR implementation progress has been steady, nearly half of US hospitals still do not have a basic EHR, and more advanced functions required for sharing care summaries and allowing patients to access their EHR are not in place at most hospitals that have implemented basic EHRs already.[7] Furthermore, the state of implementation in office‐based settings lags even farther behind hospitals.[8] Finally, our personal experience working in systems with fully integrated EHR systems has suggested to us that sometimes more shared information simply becomes part of the problem, as it is far too easy to include too many complex details of hospitalization in discharge summaries.

Moreover, as front‐line hospitalists, we generally want to help with transitional issues that occur after patients have left our hospital, and we are very mindful of the tradition of the physician who takes responsibility for all aspects of their patients' care in all settings. Yet this tradition may be more representative of the 20th century ideal of continuity than the new continuity that we see emerging in the 21st century.[9] Thus, the question at hand now is how individual physicians should prioritize and execute these tasks without overreaching.

EFFECTS OF THE PROBLEM IN PRACTICEVARIATIONS IN PHYSICIAN ENGAGEMENT

Patient needs after discharge are not uniform, and risk prediction is still imprecise despite many studies.[10] Some patients need no help; others need only targeted help with specific gaps; still others need full‐time navigators to meaningfully reduce their risk of ending up back in the emergency department.[11] The goal is to piece together the resources required to create a complete picture of patient support; much like the way ones solves a jigsaw puzzle (Figure 1A). Despite best efforts, the gaps in careor missing pieces[12]may only become apparent after discharge. Recent research suggests physicians do not see the same gaps as patients do and agree on causes for readmission less than 50% of the time.[13, 14] Often, these gaps come to light when an outside pharmacist, home health nurse, or case manager reaches out to the hospital or primary care physician to address a new problem (Figure 1B). As frequent recipients of those calls for help, we are conflicted in our reaction. On the one hand, we want to know when our carefully crafted plans fall apart. On the other hand, neither of us looks forward to voice mail messages informing us that the specialist to whom we referred the patient for follow‐up never called with an appointment. Micromanaging this kind of care can be very frustrating, both when we are the first person called or resource of last resort.

Even when physicians do not feel burdened by postdischarge care, they may be ineffective due to a lack of experience or resources. These efforts can leave them feeling demoralized, which in turn may further discourage them from future engagement, solidifying a pattern of missing (or perhaps lost) pieces (Figure 1B). Too often, a well‐intentioned but underpowered effort becomes a solution crushed by the weight of the problem. Successful physician models for care coordination must balance competing ideals of the 1 doctor, 1 patient strategy that preserve continuity,[15] with the need to focus individual physicians' time on those postdischarge tasks in which their engagement is clearly needed.

Certain payment models, such as ACOs, may help catalyze specific solutions to these problems by creating incentives for better coordination at the organizational level (eg, hospitals, skilled nursing facilities, and clinics), but these incentives may not necessarily translate into changes in physician practice, particularly as physicians payments are not yet part of bundled hospital care payments.[16] Likewise, innovative practice models such as the PCMH have promise to reshape the way healthcare is delivered, particularly by fortifying the role of primary care providers; but again, we note the lack of specific guidance for providers, particularly hospitalists. The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality defines care coordination as 1 of the 5 pillars of the PCMH, but notes considerable uncertainty about how to operationalize coordination around transitions from hospital care: A clearer understanding of, and research on, the optimal role of the PCMH in terms of leadership and care coordination in inpatient care is needed. Specifically, a better understanding of the possible approaches and the tradeoffs involved with eachin terms of access, quality, cost, and patient experiencewould be useful.[17] Early studies of these outcomes from both ACOs and PCMHs suggest improvements in some areas of patient and provider experience but not in others.[18, 19, 20, 21] Thus, we believe that although EHRs, ACOs, and PCMHs provide laudable and fundamentally necessary organizational changes to spur innovation and quality in transitions, more discussion about the specific roles for physicians is still needed. Though certainly not a definitive or exhaustive list, we provide a few specific suggestions for more effective physician engagement below.

ENABLING STRUCTURESAPPROACHES FOR MORE EFFECTIVE POSTDISCHARGE ENGAGEMENT

One approach for structuring physician participation is to create new roles for physicians as transitionalists,[22] extensivists,[23] or comprehensive‐care physicians[24] to help patients migrate from the volatile postacute period into a more stable state of recovery. Much as hospital‐based rapid response teams add a layer of additional expertise and availability without replacing the role of the attending physician, in this model, transitionalist or extensivist teams could respond to postacute issues in concert with inpatient and outpatient physicians of record.

Another approach could be to integrate the patients' hospitalists or primary care physicians into interprofessional teams modeled after hospital transfer centers, robust interdisciplinary teams that manage intense care‐coordination issues for complex inpatients. A similar approach could be used to elevate care transitions from hospital to homea postdischarge recovery center. In the same way that transfer centers develop ongoing relationships with referring hospitals and communities, postdischarge recovery centers will also need to develop working relationships with community resources like senior centers, transportation services, and the patients' physicians that provide ongoing care to be effective. A recent study of a similar concept (a virtual ward) [25] provides both a framework for this type of interprofessional collaboration and also caution in underestimating the dose or intensity of such interventions needed for those interventions to succeed. In that study, the interprofessional team was not fully integrated into the ecosystem in which patients lived, and providers frequently had difficulty communicating with the patients' ongoing caregivers, including both physicians and personal support workers.

Certainly, there are many other approaches that could be imagined, and there are pros and cons for those suggested here. Although some of these roles may seem like new types of physicians, which could worsen fragmentation, what we are suggesting is more akin to hybridization of current hospitalist and primary care provider roles. A first step could be just giving a name to the additional effort asked of these providers, and paying for time spent when they are not acting in either the inpatient attending or outpatient attending role but in the coordinating role. Fortunately, Medicare's new initiative to pay for chronic‐care management will allow physicians, clinics, and hospitals more flexibility to bill for such services that are not based on face‐to‐face encounters in the hospital or clinic.[26]

Moreover, although solving the puzzle of posthospital recovery cannot be fixed with hospitalist‐centric solutions alone, we believe more discourse is needed to define contributions from these physicians. Current policies, such as the PCMH, focus on the clinic and primary‐care providers, whereas the Medicare Readmission Reduction Program focuses on the hospital but not the hospitalist. Thus, there is a specific gap in engaging hospitalists in ongoing efforts to solve this puzzle and answer important questions about the specific role(s) of the hospitalist[27] as well as the primary care provider[28] in preventing readmissions and facilitating recovery. Certainly, integration of any new roles is needed to avoid fragmentation by default, and our suggestion of roles such as transitionalists or transfer center physicians are intended as examples to facilitate broader discussion about individual physician roles. As is often the case in healthcare, a 1 size fits all solution is unlikely, and a variety of complimentary roles may be needed to accommodate the diversity of patients and providers as well as the delivery systems where they interact.

CONCLUSION

Although the emphasis on interdisciplinary care and systems approaches in promoting recovery is welcome, individual physicians are usually overlooked in these discussions. Most physicians want to help but cannot simply do more in the absence of more creative and structured approaches. As a recent commentary on care transitions suggested, It's the how, not just the what.[29] We agree but would add, It's also about who. Thus, the time has come to engage physicians within care‐delivery models specifically designed to solve this puzzle. Although interprofessional teams are clearly needed, patients look to individuals who know them, not teams, when they run into trouble, and their first move is often to call the doctor. Because physicians play such an important role in the acute phase of illness, their struggles and efforts in the postacute phase need to be recognized and streamlined if we are to improve our patients' chances of full recovery.

Disclosure: Nothing to report.

Admission to a hospital for acute care is often a puzzling and traumatic experience for patients.[1, 2] Even after overcoming important hurdles such as receiving the right diagnosis, being treated with appropriate therapies, and experiencing initial improvement, the ultimate goal of complete recovery after discharge remains elusive for many. Dozens of interventions have been tested to reduce failed recoveries and readmissions with mixed results. Most of these have relied on system‐level changes such as improved medication reconciliation and postdischarge phone calls.[3, 4] Physicians have largely been ignored in such efforts. Most systems leave it up to individual physicians to decide how much time and effort to invest in postdischarge care, and patient outcomes are often highly dependent on a physician's skill, interest, and experience.

We are both hospitalists who attend regularly on general internal medicine services in the United States and Canada. In that capacity, we have experienced many successes and failures in helping patients recover after discharge. This Perspective frames the problem of engaging both hospitalists and office‐based physicians in transitions of care within the current context of readmission reduction efforts, and proposes a more structured approach for integrating those physicians into postdischarge care to promote recovery. Although we also consider broader policy efforts to reduce fragmentation and misaligned incentives such as electronic health records (EHRs), accountable care organizations (ACOs), and the patient‐centered medical home (PCMH), our focus is on how these may (or may not) help front‐line physicians to solve the puzzle of posthospital recovery in the current state of affairs.

THE PROBLEMLACK OF TIME, VARIABLE ENGAGEMENT, SILOED COMMUNICATION

Perhaps the most important barrier to engaging physicians in the posthospital recovery phase is their limited time and energy. Today's rapid throughput and the complexity of acute care leave little bandwidth for issues that are not right in front of hospitalists. Once discharged, patients are often out of sight, out of mind.[5] Office‐based physicians face similar time constraints.[6] In both settings, physicians find themselves operating in silos with significant communication barriers that are time consuming and difficult to overcome.

There are many current policy efforts to break down these silos, a prominent example being recent incentives to speed the widespread use of EHRs. Although EHR implementation progress has been steady, nearly half of US hospitals still do not have a basic EHR, and more advanced functions required for sharing care summaries and allowing patients to access their EHR are not in place at most hospitals that have implemented basic EHRs already.[7] Furthermore, the state of implementation in office‐based settings lags even farther behind hospitals.[8] Finally, our personal experience working in systems with fully integrated EHR systems has suggested to us that sometimes more shared information simply becomes part of the problem, as it is far too easy to include too many complex details of hospitalization in discharge summaries.

Moreover, as front‐line hospitalists, we generally want to help with transitional issues that occur after patients have left our hospital, and we are very mindful of the tradition of the physician who takes responsibility for all aspects of their patients' care in all settings. Yet this tradition may be more representative of the 20th century ideal of continuity than the new continuity that we see emerging in the 21st century.[9] Thus, the question at hand now is how individual physicians should prioritize and execute these tasks without overreaching.

EFFECTS OF THE PROBLEM IN PRACTICEVARIATIONS IN PHYSICIAN ENGAGEMENT

Patient needs after discharge are not uniform, and risk prediction is still imprecise despite many studies.[10] Some patients need no help; others need only targeted help with specific gaps; still others need full‐time navigators to meaningfully reduce their risk of ending up back in the emergency department.[11] The goal is to piece together the resources required to create a complete picture of patient support; much like the way ones solves a jigsaw puzzle (Figure 1A). Despite best efforts, the gaps in careor missing pieces[12]may only become apparent after discharge. Recent research suggests physicians do not see the same gaps as patients do and agree on causes for readmission less than 50% of the time.[13, 14] Often, these gaps come to light when an outside pharmacist, home health nurse, or case manager reaches out to the hospital or primary care physician to address a new problem (Figure 1B). As frequent recipients of those calls for help, we are conflicted in our reaction. On the one hand, we want to know when our carefully crafted plans fall apart. On the other hand, neither of us looks forward to voice mail messages informing us that the specialist to whom we referred the patient for follow‐up never called with an appointment. Micromanaging this kind of care can be very frustrating, both when we are the first person called or resource of last resort.

Even when physicians do not feel burdened by postdischarge care, they may be ineffective due to a lack of experience or resources. These efforts can leave them feeling demoralized, which in turn may further discourage them from future engagement, solidifying a pattern of missing (or perhaps lost) pieces (Figure 1B). Too often, a well‐intentioned but underpowered effort becomes a solution crushed by the weight of the problem. Successful physician models for care coordination must balance competing ideals of the 1 doctor, 1 patient strategy that preserve continuity,[15] with the need to focus individual physicians' time on those postdischarge tasks in which their engagement is clearly needed.

Certain payment models, such as ACOs, may help catalyze specific solutions to these problems by creating incentives for better coordination at the organizational level (eg, hospitals, skilled nursing facilities, and clinics), but these incentives may not necessarily translate into changes in physician practice, particularly as physicians payments are not yet part of bundled hospital care payments.[16] Likewise, innovative practice models such as the PCMH have promise to reshape the way healthcare is delivered, particularly by fortifying the role of primary care providers; but again, we note the lack of specific guidance for providers, particularly hospitalists. The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality defines care coordination as 1 of the 5 pillars of the PCMH, but notes considerable uncertainty about how to operationalize coordination around transitions from hospital care: A clearer understanding of, and research on, the optimal role of the PCMH in terms of leadership and care coordination in inpatient care is needed. Specifically, a better understanding of the possible approaches and the tradeoffs involved with eachin terms of access, quality, cost, and patient experiencewould be useful.[17] Early studies of these outcomes from both ACOs and PCMHs suggest improvements in some areas of patient and provider experience but not in others.[18, 19, 20, 21] Thus, we believe that although EHRs, ACOs, and PCMHs provide laudable and fundamentally necessary organizational changes to spur innovation and quality in transitions, more discussion about the specific roles for physicians is still needed. Though certainly not a definitive or exhaustive list, we provide a few specific suggestions for more effective physician engagement below.

ENABLING STRUCTURESAPPROACHES FOR MORE EFFECTIVE POSTDISCHARGE ENGAGEMENT

One approach for structuring physician participation is to create new roles for physicians as transitionalists,[22] extensivists,[23] or comprehensive‐care physicians[24] to help patients migrate from the volatile postacute period into a more stable state of recovery. Much as hospital‐based rapid response teams add a layer of additional expertise and availability without replacing the role of the attending physician, in this model, transitionalist or extensivist teams could respond to postacute issues in concert with inpatient and outpatient physicians of record.

Another approach could be to integrate the patients' hospitalists or primary care physicians into interprofessional teams modeled after hospital transfer centers, robust interdisciplinary teams that manage intense care‐coordination issues for complex inpatients. A similar approach could be used to elevate care transitions from hospital to homea postdischarge recovery center. In the same way that transfer centers develop ongoing relationships with referring hospitals and communities, postdischarge recovery centers will also need to develop working relationships with community resources like senior centers, transportation services, and the patients' physicians that provide ongoing care to be effective. A recent study of a similar concept (a virtual ward) [25] provides both a framework for this type of interprofessional collaboration and also caution in underestimating the dose or intensity of such interventions needed for those interventions to succeed. In that study, the interprofessional team was not fully integrated into the ecosystem in which patients lived, and providers frequently had difficulty communicating with the patients' ongoing caregivers, including both physicians and personal support workers.

Certainly, there are many other approaches that could be imagined, and there are pros and cons for those suggested here. Although some of these roles may seem like new types of physicians, which could worsen fragmentation, what we are suggesting is more akin to hybridization of current hospitalist and primary care provider roles. A first step could be just giving a name to the additional effort asked of these providers, and paying for time spent when they are not acting in either the inpatient attending or outpatient attending role but in the coordinating role. Fortunately, Medicare's new initiative to pay for chronic‐care management will allow physicians, clinics, and hospitals more flexibility to bill for such services that are not based on face‐to‐face encounters in the hospital or clinic.[26]

Moreover, although solving the puzzle of posthospital recovery cannot be fixed with hospitalist‐centric solutions alone, we believe more discourse is needed to define contributions from these physicians. Current policies, such as the PCMH, focus on the clinic and primary‐care providers, whereas the Medicare Readmission Reduction Program focuses on the hospital but not the hospitalist. Thus, there is a specific gap in engaging hospitalists in ongoing efforts to solve this puzzle and answer important questions about the specific role(s) of the hospitalist[27] as well as the primary care provider[28] in preventing readmissions and facilitating recovery. Certainly, integration of any new roles is needed to avoid fragmentation by default, and our suggestion of roles such as transitionalists or transfer center physicians are intended as examples to facilitate broader discussion about individual physician roles. As is often the case in healthcare, a 1 size fits all solution is unlikely, and a variety of complimentary roles may be needed to accommodate the diversity of patients and providers as well as the delivery systems where they interact.

CONCLUSION

Although the emphasis on interdisciplinary care and systems approaches in promoting recovery is welcome, individual physicians are usually overlooked in these discussions. Most physicians want to help but cannot simply do more in the absence of more creative and structured approaches. As a recent commentary on care transitions suggested, It's the how, not just the what.[29] We agree but would add, It's also about who. Thus, the time has come to engage physicians within care‐delivery models specifically designed to solve this puzzle. Although interprofessional teams are clearly needed, patients look to individuals who know them, not teams, when they run into trouble, and their first move is often to call the doctor. Because physicians play such an important role in the acute phase of illness, their struggles and efforts in the postacute phase need to be recognized and streamlined if we are to improve our patients' chances of full recovery.

Disclosure: Nothing to report.

- . Post‐hospital syndrome‐an acquired transient condition of generalized risk. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:2169–2170.

- , . Reducing the trauma of hospitalization. JAMA. 2014;311(21):2169–2170.

- , , , et al. Hospital‐initiated transitional care interventions as a patient safety strategy: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158:433–440.

- , , , et al. Interventions to reduce 30‐day rehospitalization: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(8):520–528.

- , , , , . “Out of sight, out of mind”: housestaff perceptions of quality‐limiting factors in discharge care at teaching hospitals. J Hosp Med. 2012;7(5):376–381.

- . Instant replay—a quarterback's view of care coordination. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:489–491.

- , , , et al. More than half of US hospitals have at least a basic EHR, but stage 2 criteria remain challenging for most. Health Aff (Millwood). 2014;33(9):1664–1671.

- , , , , , . Despite substantial progress In EHR adoption, health information exchange and patient engagement remain low in office settings. Health Aff (Millwood). 2014;33(9):1672–1679.

- , . Understanding the value of continuity in the 21st century [published online May 18, 2015]. JAMA Intern Med. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.1345.

- , , , et al. Risk prediction models for hospital readmission: a systematic review. JAMA. 2011;306(15):1688–1698.

- , , , , , . Perceptions of readmitted patients on the transition from hospital to home. J Hosp Med. 2012;7(9):709–712.

- , , , et al. “Missing pieces”—functional, social, and environmental barriers to recovery for vulnerable older adults transitioning from hospital to home. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62:1556–1561.

- , , , et al. Readmissions in the era of patient engagement. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(11):1870–1872.

- , , , et al. Challenges faced by patients with low socioeconomic status during the post‐hospital transition. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(2):283–289.

- , . Teaching physicians to care amid chaos. JAMA. 2013;309(10):987–988.

- , . Including physicians in bundled hospital care payments: time to revisit an old idea? JAMA. 2015;313(19):1907–1908.

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Coordinating care for adults with complex care needs in the patient‐centered medical home: challenges and solutions. Available at: http://www.pcmh.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/attachments/Coordinating%20Care%20for%20Adults%20with%20Complex%20Care%20Needs.pdf. Accessed June 8, 2015.

- , , , . Performance differences in year 1 of pioneer accountable care organizations. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(20):1927–1936.

- , , , . Changes in patients' experiences in Medicare Accountable Care Organizations. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(18):1715–1724.

- , , , , . Association between participation in a multipayer medical home intervention and changes in quality, utilization, and costs of care. JAMA. 2014;311(8):815–825.

- , , , et al. Patient‐centered medical home intervention at an internal medicine resident safety‐net clinic. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(18):1694–1701.

- . Walking the walk in transitional care: the “hospitalist” role expands far beyond hospital walls. Today's Hospitalist. Available at: http://www.todayshospitalist.com/index.php?b=articles_read33(5):770–777.

- , , , et al. Effect of a post‐discharge virtual ward on readmission or death for high‐risk patients: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014;312:1305–1312.

- , , . Medicare and care coordination: expanding the clinician's toolbox. JAMA. 2015;313(8):797–798.

- . Hospitalists' responsibility, role in readmission prevention. The Hospitalist. Available at: http://www.the‐hospitalist.org/article/hospitalists‐responsibility‐role‐in‐readmission‐prevention. Published April 3, 2015. Accessed July 7, 2015.

- , . Bridging the hospitalist‐primary care divide through collaborative care. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(4):308–309.

- , . Care transitions: it's the how, not just the what. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(5):539–540.

- . Post‐hospital syndrome‐an acquired transient condition of generalized risk. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:2169–2170.

- , . Reducing the trauma of hospitalization. JAMA. 2014;311(21):2169–2170.

- , , , et al. Hospital‐initiated transitional care interventions as a patient safety strategy: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158:433–440.

- , , , et al. Interventions to reduce 30‐day rehospitalization: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(8):520–528.

- , , , , . “Out of sight, out of mind”: housestaff perceptions of quality‐limiting factors in discharge care at teaching hospitals. J Hosp Med. 2012;7(5):376–381.

- . Instant replay—a quarterback's view of care coordination. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:489–491.

- , , , et al. More than half of US hospitals have at least a basic EHR, but stage 2 criteria remain challenging for most. Health Aff (Millwood). 2014;33(9):1664–1671.

- , , , , , . Despite substantial progress In EHR adoption, health information exchange and patient engagement remain low in office settings. Health Aff (Millwood). 2014;33(9):1672–1679.

- , . Understanding the value of continuity in the 21st century [published online May 18, 2015]. JAMA Intern Med. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.1345.

- , , , et al. Risk prediction models for hospital readmission: a systematic review. JAMA. 2011;306(15):1688–1698.

- , , , , , . Perceptions of readmitted patients on the transition from hospital to home. J Hosp Med. 2012;7(9):709–712.

- , , , et al. “Missing pieces”—functional, social, and environmental barriers to recovery for vulnerable older adults transitioning from hospital to home. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62:1556–1561.

- , , , et al. Readmissions in the era of patient engagement. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(11):1870–1872.

- , , , et al. Challenges faced by patients with low socioeconomic status during the post‐hospital transition. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(2):283–289.

- , . Teaching physicians to care amid chaos. JAMA. 2013;309(10):987–988.

- , . Including physicians in bundled hospital care payments: time to revisit an old idea? JAMA. 2015;313(19):1907–1908.

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Coordinating care for adults with complex care needs in the patient‐centered medical home: challenges and solutions. Available at: http://www.pcmh.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/attachments/Coordinating%20Care%20for%20Adults%20with%20Complex%20Care%20Needs.pdf. Accessed June 8, 2015.

- , , , . Performance differences in year 1 of pioneer accountable care organizations. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(20):1927–1936.

- , , , . Changes in patients' experiences in Medicare Accountable Care Organizations. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(18):1715–1724.

- , , , , . Association between participation in a multipayer medical home intervention and changes in quality, utilization, and costs of care. JAMA. 2014;311(8):815–825.

- , , , et al. Patient‐centered medical home intervention at an internal medicine resident safety‐net clinic. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(18):1694–1701.

- . Walking the walk in transitional care: the “hospitalist” role expands far beyond hospital walls. Today's Hospitalist. Available at: http://www.todayshospitalist.com/index.php?b=articles_read33(5):770–777.

- , , , et al. Effect of a post‐discharge virtual ward on readmission or death for high‐risk patients: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014;312:1305–1312.

- , , . Medicare and care coordination: expanding the clinician's toolbox. JAMA. 2015;313(8):797–798.

- . Hospitalists' responsibility, role in readmission prevention. The Hospitalist. Available at: http://www.the‐hospitalist.org/article/hospitalists‐responsibility‐role‐in‐readmission‐prevention. Published April 3, 2015. Accessed July 7, 2015.

- , . Bridging the hospitalist‐primary care divide through collaborative care. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(4):308–309.

- , . Care transitions: it's the how, not just the what. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(5):539–540.