User login

Clinical Operations Research: A New Frontier for Inquiry in Academic Health Systems

Patient throughput in healthcare systems is increasingly important to policymakers, hospital leaders, clinicians, and patients alike. In 1983, Congress passed legislation instructing the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) to implement the “prospective payment system,” which sets reimbursement for CMS hospitalizations to a fixed rate, regardless of the length of stay (LOS). Policy changes such as this coupled with increased market consolidation (ie, fewer hospitals for more patients) and increased patient acuity have created significant challenges for hospital leaders to manage patient throughput and reduce or maintain LOS.1 Additionally, emergency department (ED) overcrowding and intensive care unit (ICU) capacity strain studies have demonstrated associations with adverse patient outcomes and quality of care.2-5 Finally, and perhaps most importantly, the impact of these forces on clinicians and patients has compromised the patient-clinician relationship and patient experience. As patient throughput is important to multiple stakeholders, novel approaches to understanding and mitigating bottlenecks are imperative.

The article by Mishra and colleagues in this month’s issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine (JHM) describes one such novel methodology to evaluate patient throughput at a major academic hospital.6 The authors utilized process mapping, time and motion study, and hospital data to simulate four discrete future states for internal medicine patients that were under consideration for implementation at their institution: (1) localizing housestaff teams and patients to specific wards; (2) adding an additional 26-bed ward; (3) adding an additional hospitalist team; and (4) adding an additional ward and team and allowing for four additional patient admissions per day. Each of these approaches improved certain metrics with the tradeoff of worsening other metrics. Interestingly, geographic localization of housestaff teams and patients alone (Future State 1) resulted in decreased rounding time and patient dispersion but increased LOS and ED boarding time. Adding an additional ward (Future State 2) had the opposite effect (ie, decreased LOS and ED boarding time but increased rounding time and patient dispersion). Adding an additional hospitalist team (Future State 3) did not change LOS or ED boarding time but reduced patient dispersion and team census. Finally, adding both a ward and hospitalist team (Future State 4) reduced LOS and ED boarding time but increased rounding time and patient dispersion. These results provide a compelling case for modeling changes in clinical operations to weigh the risks and benefits of each approach with hospital priorities prior to implementation of one strategy versus another.

This study is an important step forward in bringing a rigorous scientific approach to clinical operations. If every academic center, or potentially every hospital, were to implement the approach described in this study, the potential for improvement in patient outcomes, quality metrics, and cost reduction that have been the intents of policymakers for over 30 years could be dramatic. But even if this approach were implemented (or possibly as a result of implementation), additional aspects of hospital operations might be uncovered given the infancy of this critical field. Indeed, we can think of at least five additional factors and approaches to consider as next steps to move this field forward. First, as the authors noted, multiple additional simulation inputs could be considered, including multidisciplinary workflow (eg, housestaff, hospitalists, nurses, clinical pharmacists, respiratory therapists, social workers, case managers, physical and occupational therapists, speech and language pathologists, etc.) and allowing for patients to transfer wards and teams during their hospitalizations. Second, qualitative investigation regarding clinician burnout, multidisciplinary cohesiveness, and patient satisfaction are crucial to implementation success. Third, repeat time and motion studies would aid in assessing for changes in time spent with patients and for educational purposes under the new care models. Fourth, medicine wards and teams do not operate in isolation within a hospital. It would be important to evaluate the impact of such changes on other wards and services, as all hospital wards and services are interdependent. And finally, determining costs associated with these models is critical for hospital leadership, resource allocation, implementation, and sustainability. For example, Future State 4 would increase admissions by 1,080 per year, but would that offset the cost of opening a new ward and hiring additional clinicians?

In addition, the authors feature the profoundly important concept of “geographic localization.” This construct has been investigated primarily among critically ill patients. Geographic dispersion has been shown to be associated with adverse clinical outcomes and quality metrics.7 Although this has begun to be studied among ward patients,8 the authors take this a step further by modeling future states incorporating geographic localization. Future State 4 resulted in the best overall outcomes but increased rounding time and patient dispersion, although these differences were not statistically significant. This piques our curiosity about the possibility of a fifth future state: adding geographic localization to Future State 4. Adding a new ward and new clinician team might provide a

Indeed, these results raise much broader and interesting questions surrounding ward capacity strain, that is, when patients’ demand for clinical resources exceeds availability.9 At our institution, we conducted a study to define the construct of ward capacity strain and demonstrated that among patients admitted to wards from EDs and ICUs in three University of Pennsylvania Health System hospitals, selected measures of patient volume, staff workload, and overall acuity were associated with longer ED and ICU boarding times. These same factors accounted for decreased patient throughput to varying, but sometimes large, degrees.10 We subsequently used this same definition of ward capacity strain to evaluate the association with 30-day hospital readmissions. We demonstrated that ward capacity strain metrics improved prediction of 30-day hospital readmission risk in nearly one out of three hospital wards, with medications administered, hospital discharges, and census being three of the five strongest predictors of 30-day hospital readmissions.11 These findings from our own institution further underscore the importance of the work by Mishra et al. and suggest future directions that could combine different measures of hospital throughput and patient outcomes into a more data-driven process for optimizing hospital resources, supporting the efforts of clinicians, and providing high-quality patient care.

This study is a breakthrough in the scientific rigor of hospital operations. It will lay the groundwork for a multitude of subsequent questions and studies that will move clinical operations into evidence-based practices. We find this work exciting and inspiring. We look forward to additional work from Mishra et al. and look forward to applying similar approaches to clinical operations at our institution.

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding

Dr. Kohn was supported by NIH/NHLBI F32 HL139107-01.

1. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Prospective Payment Systems. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/ProspMedicareFeeSvcPmtGen/index.html. Accessed September 26, 2018.

2. Rose L, Scales DC, Atzema C, et al. Emergency department length of stay for critical care admissions. A population-based study. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2016;13(8):1324-1332. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201511-773OC. PubMed

3. Pines JM, Localio AR, Hollander JE, et al. The impact of emergency department crowding measures on time to antibiotics for patients with community-acquired pneumonia. Ann Emerg Med. 2007;50(5):510-516. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2007.07.021. PubMed

4. Gabler NB, Ratcliffe SJ, Wagner J, et al. Mortality among patients admitted to strained intensive care units. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;188(7):800-806. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201304-0622OC. PubMed

5. Weissman GE, Gabler NB, Brown SE, Halpern SD. Intensive care unit capacity strain and adherence to prophylaxis guidelines. J Crit Care. 2015;30(6):1303-1309. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2015.08.015. PubMed

6. Mishra V, Tu S-P, Heim J, Masters H, Hall L. Predicting the future: using simulation modeling to forecast patient flow on general medicine units. J Hosp Med. 2018. In Press. PubMed

7. Vishnupriya K, Falade O, Workneh A, et al. Does sepsis treatment differ between primary and overflow intensive care units? J Hosp Med. 2012;7(8):600-605. doi: 10.1002/jhm.1955. PubMed

8. Bai AD, Srivastava S, Tomlinson GA, Smith CA, Bell CM, Gill SS. Mortality of hospitalised internal medicine patients bedspaced to non-internal medicine inpatient units: retrospective cohort study. BMJ Qual Saf. 2018;27(1):11-20. PubMed

9. Halpern SD. ICU capacity strain and the quality and allocation of critical care. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2011;17(6):648-657. doi: 10.1097/MCC.0b013e32834c7a53. PubMed

10. Kohn R, Bayes B, Ratcliffe SJ, Halpern SD, Kerlin MP. Ward capacity strain: Defining a new construct based on ED boarding time and ICU transfers. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;195:A7085.

11. Kohn R, Harhay MO, Bayes B, et al. Ward capacity strain: A novel predictor of 30-day hospital readmissions. J Gen Intern Med. 2018. doi: 10.1007/s11606-018-4564-x. PubMed

Patient throughput in healthcare systems is increasingly important to policymakers, hospital leaders, clinicians, and patients alike. In 1983, Congress passed legislation instructing the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) to implement the “prospective payment system,” which sets reimbursement for CMS hospitalizations to a fixed rate, regardless of the length of stay (LOS). Policy changes such as this coupled with increased market consolidation (ie, fewer hospitals for more patients) and increased patient acuity have created significant challenges for hospital leaders to manage patient throughput and reduce or maintain LOS.1 Additionally, emergency department (ED) overcrowding and intensive care unit (ICU) capacity strain studies have demonstrated associations with adverse patient outcomes and quality of care.2-5 Finally, and perhaps most importantly, the impact of these forces on clinicians and patients has compromised the patient-clinician relationship and patient experience. As patient throughput is important to multiple stakeholders, novel approaches to understanding and mitigating bottlenecks are imperative.

The article by Mishra and colleagues in this month’s issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine (JHM) describes one such novel methodology to evaluate patient throughput at a major academic hospital.6 The authors utilized process mapping, time and motion study, and hospital data to simulate four discrete future states for internal medicine patients that were under consideration for implementation at their institution: (1) localizing housestaff teams and patients to specific wards; (2) adding an additional 26-bed ward; (3) adding an additional hospitalist team; and (4) adding an additional ward and team and allowing for four additional patient admissions per day. Each of these approaches improved certain metrics with the tradeoff of worsening other metrics. Interestingly, geographic localization of housestaff teams and patients alone (Future State 1) resulted in decreased rounding time and patient dispersion but increased LOS and ED boarding time. Adding an additional ward (Future State 2) had the opposite effect (ie, decreased LOS and ED boarding time but increased rounding time and patient dispersion). Adding an additional hospitalist team (Future State 3) did not change LOS or ED boarding time but reduced patient dispersion and team census. Finally, adding both a ward and hospitalist team (Future State 4) reduced LOS and ED boarding time but increased rounding time and patient dispersion. These results provide a compelling case for modeling changes in clinical operations to weigh the risks and benefits of each approach with hospital priorities prior to implementation of one strategy versus another.

This study is an important step forward in bringing a rigorous scientific approach to clinical operations. If every academic center, or potentially every hospital, were to implement the approach described in this study, the potential for improvement in patient outcomes, quality metrics, and cost reduction that have been the intents of policymakers for over 30 years could be dramatic. But even if this approach were implemented (or possibly as a result of implementation), additional aspects of hospital operations might be uncovered given the infancy of this critical field. Indeed, we can think of at least five additional factors and approaches to consider as next steps to move this field forward. First, as the authors noted, multiple additional simulation inputs could be considered, including multidisciplinary workflow (eg, housestaff, hospitalists, nurses, clinical pharmacists, respiratory therapists, social workers, case managers, physical and occupational therapists, speech and language pathologists, etc.) and allowing for patients to transfer wards and teams during their hospitalizations. Second, qualitative investigation regarding clinician burnout, multidisciplinary cohesiveness, and patient satisfaction are crucial to implementation success. Third, repeat time and motion studies would aid in assessing for changes in time spent with patients and for educational purposes under the new care models. Fourth, medicine wards and teams do not operate in isolation within a hospital. It would be important to evaluate the impact of such changes on other wards and services, as all hospital wards and services are interdependent. And finally, determining costs associated with these models is critical for hospital leadership, resource allocation, implementation, and sustainability. For example, Future State 4 would increase admissions by 1,080 per year, but would that offset the cost of opening a new ward and hiring additional clinicians?

In addition, the authors feature the profoundly important concept of “geographic localization.” This construct has been investigated primarily among critically ill patients. Geographic dispersion has been shown to be associated with adverse clinical outcomes and quality metrics.7 Although this has begun to be studied among ward patients,8 the authors take this a step further by modeling future states incorporating geographic localization. Future State 4 resulted in the best overall outcomes but increased rounding time and patient dispersion, although these differences were not statistically significant. This piques our curiosity about the possibility of a fifth future state: adding geographic localization to Future State 4. Adding a new ward and new clinician team might provide a

Indeed, these results raise much broader and interesting questions surrounding ward capacity strain, that is, when patients’ demand for clinical resources exceeds availability.9 At our institution, we conducted a study to define the construct of ward capacity strain and demonstrated that among patients admitted to wards from EDs and ICUs in three University of Pennsylvania Health System hospitals, selected measures of patient volume, staff workload, and overall acuity were associated with longer ED and ICU boarding times. These same factors accounted for decreased patient throughput to varying, but sometimes large, degrees.10 We subsequently used this same definition of ward capacity strain to evaluate the association with 30-day hospital readmissions. We demonstrated that ward capacity strain metrics improved prediction of 30-day hospital readmission risk in nearly one out of three hospital wards, with medications administered, hospital discharges, and census being three of the five strongest predictors of 30-day hospital readmissions.11 These findings from our own institution further underscore the importance of the work by Mishra et al. and suggest future directions that could combine different measures of hospital throughput and patient outcomes into a more data-driven process for optimizing hospital resources, supporting the efforts of clinicians, and providing high-quality patient care.

This study is a breakthrough in the scientific rigor of hospital operations. It will lay the groundwork for a multitude of subsequent questions and studies that will move clinical operations into evidence-based practices. We find this work exciting and inspiring. We look forward to additional work from Mishra et al. and look forward to applying similar approaches to clinical operations at our institution.

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding

Dr. Kohn was supported by NIH/NHLBI F32 HL139107-01.

Patient throughput in healthcare systems is increasingly important to policymakers, hospital leaders, clinicians, and patients alike. In 1983, Congress passed legislation instructing the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) to implement the “prospective payment system,” which sets reimbursement for CMS hospitalizations to a fixed rate, regardless of the length of stay (LOS). Policy changes such as this coupled with increased market consolidation (ie, fewer hospitals for more patients) and increased patient acuity have created significant challenges for hospital leaders to manage patient throughput and reduce or maintain LOS.1 Additionally, emergency department (ED) overcrowding and intensive care unit (ICU) capacity strain studies have demonstrated associations with adverse patient outcomes and quality of care.2-5 Finally, and perhaps most importantly, the impact of these forces on clinicians and patients has compromised the patient-clinician relationship and patient experience. As patient throughput is important to multiple stakeholders, novel approaches to understanding and mitigating bottlenecks are imperative.

The article by Mishra and colleagues in this month’s issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine (JHM) describes one such novel methodology to evaluate patient throughput at a major academic hospital.6 The authors utilized process mapping, time and motion study, and hospital data to simulate four discrete future states for internal medicine patients that were under consideration for implementation at their institution: (1) localizing housestaff teams and patients to specific wards; (2) adding an additional 26-bed ward; (3) adding an additional hospitalist team; and (4) adding an additional ward and team and allowing for four additional patient admissions per day. Each of these approaches improved certain metrics with the tradeoff of worsening other metrics. Interestingly, geographic localization of housestaff teams and patients alone (Future State 1) resulted in decreased rounding time and patient dispersion but increased LOS and ED boarding time. Adding an additional ward (Future State 2) had the opposite effect (ie, decreased LOS and ED boarding time but increased rounding time and patient dispersion). Adding an additional hospitalist team (Future State 3) did not change LOS or ED boarding time but reduced patient dispersion and team census. Finally, adding both a ward and hospitalist team (Future State 4) reduced LOS and ED boarding time but increased rounding time and patient dispersion. These results provide a compelling case for modeling changes in clinical operations to weigh the risks and benefits of each approach with hospital priorities prior to implementation of one strategy versus another.

This study is an important step forward in bringing a rigorous scientific approach to clinical operations. If every academic center, or potentially every hospital, were to implement the approach described in this study, the potential for improvement in patient outcomes, quality metrics, and cost reduction that have been the intents of policymakers for over 30 years could be dramatic. But even if this approach were implemented (or possibly as a result of implementation), additional aspects of hospital operations might be uncovered given the infancy of this critical field. Indeed, we can think of at least five additional factors and approaches to consider as next steps to move this field forward. First, as the authors noted, multiple additional simulation inputs could be considered, including multidisciplinary workflow (eg, housestaff, hospitalists, nurses, clinical pharmacists, respiratory therapists, social workers, case managers, physical and occupational therapists, speech and language pathologists, etc.) and allowing for patients to transfer wards and teams during their hospitalizations. Second, qualitative investigation regarding clinician burnout, multidisciplinary cohesiveness, and patient satisfaction are crucial to implementation success. Third, repeat time and motion studies would aid in assessing for changes in time spent with patients and for educational purposes under the new care models. Fourth, medicine wards and teams do not operate in isolation within a hospital. It would be important to evaluate the impact of such changes on other wards and services, as all hospital wards and services are interdependent. And finally, determining costs associated with these models is critical for hospital leadership, resource allocation, implementation, and sustainability. For example, Future State 4 would increase admissions by 1,080 per year, but would that offset the cost of opening a new ward and hiring additional clinicians?

In addition, the authors feature the profoundly important concept of “geographic localization.” This construct has been investigated primarily among critically ill patients. Geographic dispersion has been shown to be associated with adverse clinical outcomes and quality metrics.7 Although this has begun to be studied among ward patients,8 the authors take this a step further by modeling future states incorporating geographic localization. Future State 4 resulted in the best overall outcomes but increased rounding time and patient dispersion, although these differences were not statistically significant. This piques our curiosity about the possibility of a fifth future state: adding geographic localization to Future State 4. Adding a new ward and new clinician team might provide a

Indeed, these results raise much broader and interesting questions surrounding ward capacity strain, that is, when patients’ demand for clinical resources exceeds availability.9 At our institution, we conducted a study to define the construct of ward capacity strain and demonstrated that among patients admitted to wards from EDs and ICUs in three University of Pennsylvania Health System hospitals, selected measures of patient volume, staff workload, and overall acuity were associated with longer ED and ICU boarding times. These same factors accounted for decreased patient throughput to varying, but sometimes large, degrees.10 We subsequently used this same definition of ward capacity strain to evaluate the association with 30-day hospital readmissions. We demonstrated that ward capacity strain metrics improved prediction of 30-day hospital readmission risk in nearly one out of three hospital wards, with medications administered, hospital discharges, and census being three of the five strongest predictors of 30-day hospital readmissions.11 These findings from our own institution further underscore the importance of the work by Mishra et al. and suggest future directions that could combine different measures of hospital throughput and patient outcomes into a more data-driven process for optimizing hospital resources, supporting the efforts of clinicians, and providing high-quality patient care.

This study is a breakthrough in the scientific rigor of hospital operations. It will lay the groundwork for a multitude of subsequent questions and studies that will move clinical operations into evidence-based practices. We find this work exciting and inspiring. We look forward to additional work from Mishra et al. and look forward to applying similar approaches to clinical operations at our institution.

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding

Dr. Kohn was supported by NIH/NHLBI F32 HL139107-01.

1. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Prospective Payment Systems. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/ProspMedicareFeeSvcPmtGen/index.html. Accessed September 26, 2018.

2. Rose L, Scales DC, Atzema C, et al. Emergency department length of stay for critical care admissions. A population-based study. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2016;13(8):1324-1332. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201511-773OC. PubMed

3. Pines JM, Localio AR, Hollander JE, et al. The impact of emergency department crowding measures on time to antibiotics for patients with community-acquired pneumonia. Ann Emerg Med. 2007;50(5):510-516. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2007.07.021. PubMed

4. Gabler NB, Ratcliffe SJ, Wagner J, et al. Mortality among patients admitted to strained intensive care units. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;188(7):800-806. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201304-0622OC. PubMed

5. Weissman GE, Gabler NB, Brown SE, Halpern SD. Intensive care unit capacity strain and adherence to prophylaxis guidelines. J Crit Care. 2015;30(6):1303-1309. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2015.08.015. PubMed

6. Mishra V, Tu S-P, Heim J, Masters H, Hall L. Predicting the future: using simulation modeling to forecast patient flow on general medicine units. J Hosp Med. 2018. In Press. PubMed

7. Vishnupriya K, Falade O, Workneh A, et al. Does sepsis treatment differ between primary and overflow intensive care units? J Hosp Med. 2012;7(8):600-605. doi: 10.1002/jhm.1955. PubMed

8. Bai AD, Srivastava S, Tomlinson GA, Smith CA, Bell CM, Gill SS. Mortality of hospitalised internal medicine patients bedspaced to non-internal medicine inpatient units: retrospective cohort study. BMJ Qual Saf. 2018;27(1):11-20. PubMed

9. Halpern SD. ICU capacity strain and the quality and allocation of critical care. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2011;17(6):648-657. doi: 10.1097/MCC.0b013e32834c7a53. PubMed

10. Kohn R, Bayes B, Ratcliffe SJ, Halpern SD, Kerlin MP. Ward capacity strain: Defining a new construct based on ED boarding time and ICU transfers. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;195:A7085.

11. Kohn R, Harhay MO, Bayes B, et al. Ward capacity strain: A novel predictor of 30-day hospital readmissions. J Gen Intern Med. 2018. doi: 10.1007/s11606-018-4564-x. PubMed

1. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Prospective Payment Systems. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/ProspMedicareFeeSvcPmtGen/index.html. Accessed September 26, 2018.

2. Rose L, Scales DC, Atzema C, et al. Emergency department length of stay for critical care admissions. A population-based study. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2016;13(8):1324-1332. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201511-773OC. PubMed

3. Pines JM, Localio AR, Hollander JE, et al. The impact of emergency department crowding measures on time to antibiotics for patients with community-acquired pneumonia. Ann Emerg Med. 2007;50(5):510-516. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2007.07.021. PubMed

4. Gabler NB, Ratcliffe SJ, Wagner J, et al. Mortality among patients admitted to strained intensive care units. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;188(7):800-806. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201304-0622OC. PubMed

5. Weissman GE, Gabler NB, Brown SE, Halpern SD. Intensive care unit capacity strain and adherence to prophylaxis guidelines. J Crit Care. 2015;30(6):1303-1309. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2015.08.015. PubMed

6. Mishra V, Tu S-P, Heim J, Masters H, Hall L. Predicting the future: using simulation modeling to forecast patient flow on general medicine units. J Hosp Med. 2018. In Press. PubMed

7. Vishnupriya K, Falade O, Workneh A, et al. Does sepsis treatment differ between primary and overflow intensive care units? J Hosp Med. 2012;7(8):600-605. doi: 10.1002/jhm.1955. PubMed

8. Bai AD, Srivastava S, Tomlinson GA, Smith CA, Bell CM, Gill SS. Mortality of hospitalised internal medicine patients bedspaced to non-internal medicine inpatient units: retrospective cohort study. BMJ Qual Saf. 2018;27(1):11-20. PubMed

9. Halpern SD. ICU capacity strain and the quality and allocation of critical care. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2011;17(6):648-657. doi: 10.1097/MCC.0b013e32834c7a53. PubMed

10. Kohn R, Bayes B, Ratcliffe SJ, Halpern SD, Kerlin MP. Ward capacity strain: Defining a new construct based on ED boarding time and ICU transfers. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;195:A7085.

11. Kohn R, Harhay MO, Bayes B, et al. Ward capacity strain: A novel predictor of 30-day hospital readmissions. J Gen Intern Med. 2018. doi: 10.1007/s11606-018-4564-x. PubMed

© 2019 Society of Hospital Medicine

The Role of the Medical Consultant in 2018: Putting It All Together

Whenever the principles of effective medical consultation are discussed, a classic article published in 1983 by Lee Goldman et al. is invariably referenced. In the “Ten Commandments for Effective Consultation,” Goldman argued that internists should “determine the question, establish urgency, look for yourself, be as brief as appropriate, be specific, provide contingency plans, honor thy turf, teach with tact, provide direct personal contact, and follow up.”1 If these Ten Commandments were followed, then the consultation would be more effective and satisfactory for both the consultant and the referring provider. However, with the advent of comanagement in 1994 where internists and surgeons have a “shared responsibility and accountability,”2 there has been a shift, and the once-concrete definitions of a specific reason for consult and the nature of “turf” have become blurred. Since 1994, the use of medical consultation and comanagement has skyrocketed, and today, more than 50% of surgical patients have a medical consultation or comanagement.3 This may be due to increased time pressures on surgeons and better outcomes of comanaged patients (eg, fewer postoperative complications, fewer transfers to an intensive care unit for acute medical deterioration, and increased likelihood to discharge to home).4

Medical management of surgical patients in the hospital involves a different skill set than that required to manage general medical patients. Accordingly, in 2012, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) made medical consultation and perioperative care an End of Training Entrustable Professional Activities and ACGME subcompetency. Earlier this year, a nationwide perioperative curriculum for graduate medical education was consisting of eight objective and core topic modules and pretest/posttest questions selected from SHMConsults.com, including assessment and management of perioperative cardiac and pulmonary risk and management of diabetes, perioperative fever, and anticoagulants. Trainees were assessed using the multiple-choice questions, observed mini-cex, and written evaluation of a consultation report. Despite this encouraging development of curricula and competencies for trainees, there are still important gaps in our knowledge of basic patterns for consultation practices. For example, the type of patients and medical conditions currently encountered on our medical consultation and comanagement services had been previously unknown.

In the December issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine, Wang et al. answer this question through the first cross-sectional multicenter prospective survey to examine medical consultation/comanagement practices since observational studies in the 1970-1990s.6 In a sample of 1,264 consultation requests from 11 academic medical centers over four two-week periods from July 2014 through July 2015, they found that the most common requests for consultation were medical management/comanagement, preoperative evaluation, blood pressure management, and other common postoperative complications, including postoperative atrial fibrillation, heart failure, renal failure, hyponatremia, anemia, hypoxia, and altered mental status.9 The majority of referrals were from orthopedic surgery and neurosurgery. They also found that medical consultants and comanagers provided comprehensive evaluations where more than a third of encounters addressed issues that were not stated in the initial reason for consult (RFC) and that consultants addressed more than two RFCs per encounter.9

These findings illustrate the paradigm shift of medical consultation focusing on a single specific question to addressing and optimizing the entire patient. This shift toward a broader, more open-ended reason for consultation may present some challenges such as “dumping” where referring surgeons and other specialists signoff their patients after surgery is completed, with internists processing the surgeons’ patients through the hospitalization. These challenges can be mitigated with predefined comanagement agreements with clearly defined roles and collaborative professional relationships.

Nonetheless, given the recent developments in curricula and training competencies mentioned above, internists are better equipped than ever before to put everything together and take care of the medical conditions of the increasingly complex and older surgical patient. For example, if one is consulted to see a patient for postoperative hypertension, it is difficult to not address the patient’s blood sugars in the 300s, lack of venous thromboembolism prophylaxis, delirium, acute renal failure, and acute blood loss anemia. The authors are correct to assert it is critically important to ensure that this input is desired by the referring physician either via verbal communication or comanagement agreements.

The findings of Wang et al. suggest some important future steps in medical consultation to ensure that our trainees and colleagues are prepared to take care of the entire patient regardless of whether the patient is on a consultant or comanagement agreement. This study shows that trainees are exposed to a diverse clinical experience on our medical consultation and comanagement services, which is in accordance with the objectives, assessment tools, and modules of the nationwide curriculum. It is likely that comanagement services will continue to expand as more of our medically complex patients will need either elective or emergency surgeries and surgeons have become less comfortable managing these patients on their own. We also may be asked to participate in quality improvement initiatives in the management of surgical patients, including the “perioperative surgical home programs,” where physicians work on a patient-centered approach to the surgical patient using evidence-based standard clinical care pathways and transitions from before surgery to postdischarge.7 We should share our experiences in quality improvement and the patient-centered medical home to ensure that our patients are optimized for surgery and beyond. As Lee Goldman et al. stated in the “Ten Commandments for Effective Consultations,1” consultative medicine is an important part of an internal medicine practice. Today, more than ever, the consultant or comanagement role or roles

1. Goldman L, Lee T, Rudd P. Ten commandments for effective consultations. Arch Intern Med. 1983;143(9):1753-1755. PubMed

2. Macpherson DS, Parenti C, Nee J, et al. An internist joins the surgery service: does comanagement make a difference? J Gen Intern Med 1994;9:440-446. PubMed

3. Chen, LM, Wilk, AS, Thumma, JR et al. Use of medical consultants for hospitalized surgical patients. An observational cohort study. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(9):1470-1477. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.3376. PubMed

4. Kammerlander C, Roth T, Friedman SM, et al. Ortho-geriatric service–a literature review comparing different models. Osteoporos Int. 2010;21(Suppl 4):S637-S646. doi: 10.1007/s00198-010-1396-x. PubMed

5. Fang M, O’Glasser A, Sahai S, Pfeifer K, Johnson KM, Kuperman E. Development of a nationwide consensus curriculum of perioperative medicine: a modified Delphi method. Periop Care Oper Room Manag. 2018;12:31-34. doi: 10.1016/j.pcorm.2018.09.002.

6. Wang ES, Moreland C, Shoffeitt M, Leykum LK. Who consults us and why? An evaluation of medicine consult/co-management services at academic medical centers. J Hosp Med. 2018;12(4):840-843. doi: 10.12788/jhm.3010. PubMed

7. Kain ZN, Vakharia S, Garson L, et al. The perioperative surgical home as a future perioperative practice model. Anesth Analg. 2014;118(5):1126-1130. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000000190. PubMed

Whenever the principles of effective medical consultation are discussed, a classic article published in 1983 by Lee Goldman et al. is invariably referenced. In the “Ten Commandments for Effective Consultation,” Goldman argued that internists should “determine the question, establish urgency, look for yourself, be as brief as appropriate, be specific, provide contingency plans, honor thy turf, teach with tact, provide direct personal contact, and follow up.”1 If these Ten Commandments were followed, then the consultation would be more effective and satisfactory for both the consultant and the referring provider. However, with the advent of comanagement in 1994 where internists and surgeons have a “shared responsibility and accountability,”2 there has been a shift, and the once-concrete definitions of a specific reason for consult and the nature of “turf” have become blurred. Since 1994, the use of medical consultation and comanagement has skyrocketed, and today, more than 50% of surgical patients have a medical consultation or comanagement.3 This may be due to increased time pressures on surgeons and better outcomes of comanaged patients (eg, fewer postoperative complications, fewer transfers to an intensive care unit for acute medical deterioration, and increased likelihood to discharge to home).4

Medical management of surgical patients in the hospital involves a different skill set than that required to manage general medical patients. Accordingly, in 2012, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) made medical consultation and perioperative care an End of Training Entrustable Professional Activities and ACGME subcompetency. Earlier this year, a nationwide perioperative curriculum for graduate medical education was consisting of eight objective and core topic modules and pretest/posttest questions selected from SHMConsults.com, including assessment and management of perioperative cardiac and pulmonary risk and management of diabetes, perioperative fever, and anticoagulants. Trainees were assessed using the multiple-choice questions, observed mini-cex, and written evaluation of a consultation report. Despite this encouraging development of curricula and competencies for trainees, there are still important gaps in our knowledge of basic patterns for consultation practices. For example, the type of patients and medical conditions currently encountered on our medical consultation and comanagement services had been previously unknown.

In the December issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine, Wang et al. answer this question through the first cross-sectional multicenter prospective survey to examine medical consultation/comanagement practices since observational studies in the 1970-1990s.6 In a sample of 1,264 consultation requests from 11 academic medical centers over four two-week periods from July 2014 through July 2015, they found that the most common requests for consultation were medical management/comanagement, preoperative evaluation, blood pressure management, and other common postoperative complications, including postoperative atrial fibrillation, heart failure, renal failure, hyponatremia, anemia, hypoxia, and altered mental status.9 The majority of referrals were from orthopedic surgery and neurosurgery. They also found that medical consultants and comanagers provided comprehensive evaluations where more than a third of encounters addressed issues that were not stated in the initial reason for consult (RFC) and that consultants addressed more than two RFCs per encounter.9

These findings illustrate the paradigm shift of medical consultation focusing on a single specific question to addressing and optimizing the entire patient. This shift toward a broader, more open-ended reason for consultation may present some challenges such as “dumping” where referring surgeons and other specialists signoff their patients after surgery is completed, with internists processing the surgeons’ patients through the hospitalization. These challenges can be mitigated with predefined comanagement agreements with clearly defined roles and collaborative professional relationships.

Nonetheless, given the recent developments in curricula and training competencies mentioned above, internists are better equipped than ever before to put everything together and take care of the medical conditions of the increasingly complex and older surgical patient. For example, if one is consulted to see a patient for postoperative hypertension, it is difficult to not address the patient’s blood sugars in the 300s, lack of venous thromboembolism prophylaxis, delirium, acute renal failure, and acute blood loss anemia. The authors are correct to assert it is critically important to ensure that this input is desired by the referring physician either via verbal communication or comanagement agreements.

The findings of Wang et al. suggest some important future steps in medical consultation to ensure that our trainees and colleagues are prepared to take care of the entire patient regardless of whether the patient is on a consultant or comanagement agreement. This study shows that trainees are exposed to a diverse clinical experience on our medical consultation and comanagement services, which is in accordance with the objectives, assessment tools, and modules of the nationwide curriculum. It is likely that comanagement services will continue to expand as more of our medically complex patients will need either elective or emergency surgeries and surgeons have become less comfortable managing these patients on their own. We also may be asked to participate in quality improvement initiatives in the management of surgical patients, including the “perioperative surgical home programs,” where physicians work on a patient-centered approach to the surgical patient using evidence-based standard clinical care pathways and transitions from before surgery to postdischarge.7 We should share our experiences in quality improvement and the patient-centered medical home to ensure that our patients are optimized for surgery and beyond. As Lee Goldman et al. stated in the “Ten Commandments for Effective Consultations,1” consultative medicine is an important part of an internal medicine practice. Today, more than ever, the consultant or comanagement role or roles

Whenever the principles of effective medical consultation are discussed, a classic article published in 1983 by Lee Goldman et al. is invariably referenced. In the “Ten Commandments for Effective Consultation,” Goldman argued that internists should “determine the question, establish urgency, look for yourself, be as brief as appropriate, be specific, provide contingency plans, honor thy turf, teach with tact, provide direct personal contact, and follow up.”1 If these Ten Commandments were followed, then the consultation would be more effective and satisfactory for both the consultant and the referring provider. However, with the advent of comanagement in 1994 where internists and surgeons have a “shared responsibility and accountability,”2 there has been a shift, and the once-concrete definitions of a specific reason for consult and the nature of “turf” have become blurred. Since 1994, the use of medical consultation and comanagement has skyrocketed, and today, more than 50% of surgical patients have a medical consultation or comanagement.3 This may be due to increased time pressures on surgeons and better outcomes of comanaged patients (eg, fewer postoperative complications, fewer transfers to an intensive care unit for acute medical deterioration, and increased likelihood to discharge to home).4

Medical management of surgical patients in the hospital involves a different skill set than that required to manage general medical patients. Accordingly, in 2012, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) made medical consultation and perioperative care an End of Training Entrustable Professional Activities and ACGME subcompetency. Earlier this year, a nationwide perioperative curriculum for graduate medical education was consisting of eight objective and core topic modules and pretest/posttest questions selected from SHMConsults.com, including assessment and management of perioperative cardiac and pulmonary risk and management of diabetes, perioperative fever, and anticoagulants. Trainees were assessed using the multiple-choice questions, observed mini-cex, and written evaluation of a consultation report. Despite this encouraging development of curricula and competencies for trainees, there are still important gaps in our knowledge of basic patterns for consultation practices. For example, the type of patients and medical conditions currently encountered on our medical consultation and comanagement services had been previously unknown.

In the December issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine, Wang et al. answer this question through the first cross-sectional multicenter prospective survey to examine medical consultation/comanagement practices since observational studies in the 1970-1990s.6 In a sample of 1,264 consultation requests from 11 academic medical centers over four two-week periods from July 2014 through July 2015, they found that the most common requests for consultation were medical management/comanagement, preoperative evaluation, blood pressure management, and other common postoperative complications, including postoperative atrial fibrillation, heart failure, renal failure, hyponatremia, anemia, hypoxia, and altered mental status.9 The majority of referrals were from orthopedic surgery and neurosurgery. They also found that medical consultants and comanagers provided comprehensive evaluations where more than a third of encounters addressed issues that were not stated in the initial reason for consult (RFC) and that consultants addressed more than two RFCs per encounter.9

These findings illustrate the paradigm shift of medical consultation focusing on a single specific question to addressing and optimizing the entire patient. This shift toward a broader, more open-ended reason for consultation may present some challenges such as “dumping” where referring surgeons and other specialists signoff their patients after surgery is completed, with internists processing the surgeons’ patients through the hospitalization. These challenges can be mitigated with predefined comanagement agreements with clearly defined roles and collaborative professional relationships.

Nonetheless, given the recent developments in curricula and training competencies mentioned above, internists are better equipped than ever before to put everything together and take care of the medical conditions of the increasingly complex and older surgical patient. For example, if one is consulted to see a patient for postoperative hypertension, it is difficult to not address the patient’s blood sugars in the 300s, lack of venous thromboembolism prophylaxis, delirium, acute renal failure, and acute blood loss anemia. The authors are correct to assert it is critically important to ensure that this input is desired by the referring physician either via verbal communication or comanagement agreements.

The findings of Wang et al. suggest some important future steps in medical consultation to ensure that our trainees and colleagues are prepared to take care of the entire patient regardless of whether the patient is on a consultant or comanagement agreement. This study shows that trainees are exposed to a diverse clinical experience on our medical consultation and comanagement services, which is in accordance with the objectives, assessment tools, and modules of the nationwide curriculum. It is likely that comanagement services will continue to expand as more of our medically complex patients will need either elective or emergency surgeries and surgeons have become less comfortable managing these patients on their own. We also may be asked to participate in quality improvement initiatives in the management of surgical patients, including the “perioperative surgical home programs,” where physicians work on a patient-centered approach to the surgical patient using evidence-based standard clinical care pathways and transitions from before surgery to postdischarge.7 We should share our experiences in quality improvement and the patient-centered medical home to ensure that our patients are optimized for surgery and beyond. As Lee Goldman et al. stated in the “Ten Commandments for Effective Consultations,1” consultative medicine is an important part of an internal medicine practice. Today, more than ever, the consultant or comanagement role or roles

1. Goldman L, Lee T, Rudd P. Ten commandments for effective consultations. Arch Intern Med. 1983;143(9):1753-1755. PubMed

2. Macpherson DS, Parenti C, Nee J, et al. An internist joins the surgery service: does comanagement make a difference? J Gen Intern Med 1994;9:440-446. PubMed

3. Chen, LM, Wilk, AS, Thumma, JR et al. Use of medical consultants for hospitalized surgical patients. An observational cohort study. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(9):1470-1477. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.3376. PubMed

4. Kammerlander C, Roth T, Friedman SM, et al. Ortho-geriatric service–a literature review comparing different models. Osteoporos Int. 2010;21(Suppl 4):S637-S646. doi: 10.1007/s00198-010-1396-x. PubMed

5. Fang M, O’Glasser A, Sahai S, Pfeifer K, Johnson KM, Kuperman E. Development of a nationwide consensus curriculum of perioperative medicine: a modified Delphi method. Periop Care Oper Room Manag. 2018;12:31-34. doi: 10.1016/j.pcorm.2018.09.002.

6. Wang ES, Moreland C, Shoffeitt M, Leykum LK. Who consults us and why? An evaluation of medicine consult/co-management services at academic medical centers. J Hosp Med. 2018;12(4):840-843. doi: 10.12788/jhm.3010. PubMed

7. Kain ZN, Vakharia S, Garson L, et al. The perioperative surgical home as a future perioperative practice model. Anesth Analg. 2014;118(5):1126-1130. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000000190. PubMed

1. Goldman L, Lee T, Rudd P. Ten commandments for effective consultations. Arch Intern Med. 1983;143(9):1753-1755. PubMed

2. Macpherson DS, Parenti C, Nee J, et al. An internist joins the surgery service: does comanagement make a difference? J Gen Intern Med 1994;9:440-446. PubMed

3. Chen, LM, Wilk, AS, Thumma, JR et al. Use of medical consultants for hospitalized surgical patients. An observational cohort study. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(9):1470-1477. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.3376. PubMed

4. Kammerlander C, Roth T, Friedman SM, et al. Ortho-geriatric service–a literature review comparing different models. Osteoporos Int. 2010;21(Suppl 4):S637-S646. doi: 10.1007/s00198-010-1396-x. PubMed

5. Fang M, O’Glasser A, Sahai S, Pfeifer K, Johnson KM, Kuperman E. Development of a nationwide consensus curriculum of perioperative medicine: a modified Delphi method. Periop Care Oper Room Manag. 2018;12:31-34. doi: 10.1016/j.pcorm.2018.09.002.

6. Wang ES, Moreland C, Shoffeitt M, Leykum LK. Who consults us and why? An evaluation of medicine consult/co-management services at academic medical centers. J Hosp Med. 2018;12(4):840-843. doi: 10.12788/jhm.3010. PubMed

7. Kain ZN, Vakharia S, Garson L, et al. The perioperative surgical home as a future perioperative practice model. Anesth Analg. 2014;118(5):1126-1130. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000000190. PubMed

© 2019 Society of Hospital Medicine

Mobility assessment in the hospital: What are the “next steps”?

Mobility impairment (reduced ability to change body position or ambulate) is common among older adults during hospitalization1 and is correlated with higher rates of readmission,2 long-term care placement,3 and even death.4 Although some may perceive mobility impairment during hospitalization as a temporary inconvenience, recent research suggests disruptions of basic activities of daily life such as mobility may be “traumatic” 5 or “toxic”6 to older adults with long-term post-hospital effects.7 While these studies highlight the underestimated effects of low mobility during hospitalization, they are based on data collected for research purposes using mobility measurement tools not typically utilized in routine hospital care.

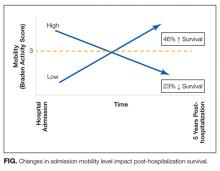

The absence of a standardized mobility measurement tool used as part of routine hospital care poses a barrier to estimating the effects of low hospital mobility and programs seeking to improve mobility levels in hospitalized patients. In this issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine, Valiani et al.8 found a novel approach to measure mobility using a universally disseminated clinical scale (Braden). Using the activity subscale of the Braden scale, the authors found that mobility level changes during hospitalization can have a striking impact on post-discharge mortality. Their results indicate that older adults who develop mobility impairment during hospitalization had higher odds of death, specifically 1.23 times greater risk, within 6 months after discharge (23% decreased chance of survival). Most of the risk applies in the first 30 days and remains to a lesser extent for up to 5 years post-hospitalization. An equally interesting finding was that those who enter the hospital with low mobility but improve have a 46% higher survival rate. Again, most of the benefit is seen during hospitalization or immediately afterward, but the benefit persists for up to 5 years. A schematic of the results are presented in the Figure. Notably, Valiani et al.8 did not find regression to the mean Braden score of 3.

This novel use of the Braden activity subscale raises a question: Should we be using the Braden activity component to measure mobility in the hospital? Put another way, what scale should we be using in the hospital? Using the Braden activity subscale is convenient, since it capitalizes on data already being gathered. However, this subscale focuses solely on ambulation frequency; it doesn’t capture other mobility domains, such as ability to change body position. Ambulation is only half of the mobility story. It is interesting that although the Braden scale does have a mobility subscale that captures body position changes, the authors chose not to use it. This begs the question of whether an ideal mobility scale should encompass both components.

Previous studies of hospital mobility have deployed tools such as Katz Activities of Daily Living (ADLs)9 and the Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB),10 and there is a recent trend toward using the Activity Measure for Post-Acute Care (AM-PAC).11 However, none of these tools, including the one discussed in this review, were designed to capture mobility levels in hospitalized patients. The Katz ADLs and the SPPB were designed for community living adults, and the AM-PAC was designed for a more mobile post-acute-care patient population. Although these tools do have limitations for use with hospitalized patients, they have shown promising results.10,12

What does all this mean for implementation? Do we have enough data on the existing scales to say we should be implementing them—or in the case of Braden, continuing to use them—to measure function and mobility in hospitalized patients? Implementing an ideal mobility assessment tool into the routinized care of the hospital patient may be necessary but insufficient. Complementing the use of these tools with more objective and precise mobility measures (eg, activity counts or steps from wearable sensors) would greatly increase the ability to accurately assess mobility and potentially enable providers to recommend specific mobility goals for patients in the form of steps or minutes of activity per day. In conclusion, the provocative results by Valiani et al.8 underscore the importance of mobility for hospitalized patients but also suggest many opportunities for future research and implementation to improve hospital care, especially for older adults.

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

1. Covinsky KE, Pierluissi E, Johnston CB. Hospitalization-associated disability: “She was probably able to ambulate, but I’m not sure.” JAMA. 2011;306(16):1782-1793. PubMed

2. Greysen SR, Stijacic Cenzer I, Auerbach AD, Covinsky KE. Functional impairment and hospital readmission in Medicare seniors. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(4):559-565. PubMed

3. Covinsky KE, Palmer RM, Fortinsky RH, et al. Loss of independence in activities of daily living in older adults hospitalized with medical illnesses: increased vulnerability with age. J Amer Geriatr Soc. 2003;51(4):451-458. PubMed

4. Barnes DE, Mehta KM, Boscardin WJ, et al. Prediction of recovery, dependence or death in elders who become disabled during hospitalization. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28(2):261-268. PubMed

5. Detsky AS, Krumholz HM. Reducing the trauma of hospitalization. JAMA. 2014;311(21):2169-2170. PubMed

6. Creditor MC. Hazards of hospitalization of the elderly. Ann Intern Med. 1993;118(3):219-223. PubMed

7. Krumholz HM. Post-hospital syndrome—an acquired, transient condition of generalized risk. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(2):100-102. PubMed

8. Valiani V, Chen Z, Lipori G, Pahor M, Sabbá C, Manini TM. Prognostic value of Braden activity subscale for mobility status in hospitalized older adults. J Hosp Med. 2017;12(6):396-401. PubMed

9. Katz S, Ford AB, Moskowitz RW, Jackson BA, Jaffe MW. Studies of illness in the aged. The index of ADL: a standardized measure of biological and psychosocial function. JAMA. 1963;185:914-919. PubMed

10. Guralnik JM, Simonsick EM, Ferrucci L, et al. A short physical performance battery assessing lower extremity function: association with self-reported disability and prediction of mortality and nursing home admission. J Gerontol A Bio Sci Med Sci. 1994;49(2):M85-M94. PubMed

11. Haley SM, Andres PL, Coster WJ, Kosinski M, Ni P, Jette AM. Short-form activity measure for post-acute care. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2004;85(4):649-660. PubMed

12. Wallace M, Shelkey M. Monitoring functional status in hospitalized older adults. Am J Nurs. 2008;108(4):64-71. PubMed

Mobility impairment (reduced ability to change body position or ambulate) is common among older adults during hospitalization1 and is correlated with higher rates of readmission,2 long-term care placement,3 and even death.4 Although some may perceive mobility impairment during hospitalization as a temporary inconvenience, recent research suggests disruptions of basic activities of daily life such as mobility may be “traumatic” 5 or “toxic”6 to older adults with long-term post-hospital effects.7 While these studies highlight the underestimated effects of low mobility during hospitalization, they are based on data collected for research purposes using mobility measurement tools not typically utilized in routine hospital care.

The absence of a standardized mobility measurement tool used as part of routine hospital care poses a barrier to estimating the effects of low hospital mobility and programs seeking to improve mobility levels in hospitalized patients. In this issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine, Valiani et al.8 found a novel approach to measure mobility using a universally disseminated clinical scale (Braden). Using the activity subscale of the Braden scale, the authors found that mobility level changes during hospitalization can have a striking impact on post-discharge mortality. Their results indicate that older adults who develop mobility impairment during hospitalization had higher odds of death, specifically 1.23 times greater risk, within 6 months after discharge (23% decreased chance of survival). Most of the risk applies in the first 30 days and remains to a lesser extent for up to 5 years post-hospitalization. An equally interesting finding was that those who enter the hospital with low mobility but improve have a 46% higher survival rate. Again, most of the benefit is seen during hospitalization or immediately afterward, but the benefit persists for up to 5 years. A schematic of the results are presented in the Figure. Notably, Valiani et al.8 did not find regression to the mean Braden score of 3.

This novel use of the Braden activity subscale raises a question: Should we be using the Braden activity component to measure mobility in the hospital? Put another way, what scale should we be using in the hospital? Using the Braden activity subscale is convenient, since it capitalizes on data already being gathered. However, this subscale focuses solely on ambulation frequency; it doesn’t capture other mobility domains, such as ability to change body position. Ambulation is only half of the mobility story. It is interesting that although the Braden scale does have a mobility subscale that captures body position changes, the authors chose not to use it. This begs the question of whether an ideal mobility scale should encompass both components.

Previous studies of hospital mobility have deployed tools such as Katz Activities of Daily Living (ADLs)9 and the Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB),10 and there is a recent trend toward using the Activity Measure for Post-Acute Care (AM-PAC).11 However, none of these tools, including the one discussed in this review, were designed to capture mobility levels in hospitalized patients. The Katz ADLs and the SPPB were designed for community living adults, and the AM-PAC was designed for a more mobile post-acute-care patient population. Although these tools do have limitations for use with hospitalized patients, they have shown promising results.10,12

What does all this mean for implementation? Do we have enough data on the existing scales to say we should be implementing them—or in the case of Braden, continuing to use them—to measure function and mobility in hospitalized patients? Implementing an ideal mobility assessment tool into the routinized care of the hospital patient may be necessary but insufficient. Complementing the use of these tools with more objective and precise mobility measures (eg, activity counts or steps from wearable sensors) would greatly increase the ability to accurately assess mobility and potentially enable providers to recommend specific mobility goals for patients in the form of steps or minutes of activity per day. In conclusion, the provocative results by Valiani et al.8 underscore the importance of mobility for hospitalized patients but also suggest many opportunities for future research and implementation to improve hospital care, especially for older adults.

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

Mobility impairment (reduced ability to change body position or ambulate) is common among older adults during hospitalization1 and is correlated with higher rates of readmission,2 long-term care placement,3 and even death.4 Although some may perceive mobility impairment during hospitalization as a temporary inconvenience, recent research suggests disruptions of basic activities of daily life such as mobility may be “traumatic” 5 or “toxic”6 to older adults with long-term post-hospital effects.7 While these studies highlight the underestimated effects of low mobility during hospitalization, they are based on data collected for research purposes using mobility measurement tools not typically utilized in routine hospital care.

The absence of a standardized mobility measurement tool used as part of routine hospital care poses a barrier to estimating the effects of low hospital mobility and programs seeking to improve mobility levels in hospitalized patients. In this issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine, Valiani et al.8 found a novel approach to measure mobility using a universally disseminated clinical scale (Braden). Using the activity subscale of the Braden scale, the authors found that mobility level changes during hospitalization can have a striking impact on post-discharge mortality. Their results indicate that older adults who develop mobility impairment during hospitalization had higher odds of death, specifically 1.23 times greater risk, within 6 months after discharge (23% decreased chance of survival). Most of the risk applies in the first 30 days and remains to a lesser extent for up to 5 years post-hospitalization. An equally interesting finding was that those who enter the hospital with low mobility but improve have a 46% higher survival rate. Again, most of the benefit is seen during hospitalization or immediately afterward, but the benefit persists for up to 5 years. A schematic of the results are presented in the Figure. Notably, Valiani et al.8 did not find regression to the mean Braden score of 3.

This novel use of the Braden activity subscale raises a question: Should we be using the Braden activity component to measure mobility in the hospital? Put another way, what scale should we be using in the hospital? Using the Braden activity subscale is convenient, since it capitalizes on data already being gathered. However, this subscale focuses solely on ambulation frequency; it doesn’t capture other mobility domains, such as ability to change body position. Ambulation is only half of the mobility story. It is interesting that although the Braden scale does have a mobility subscale that captures body position changes, the authors chose not to use it. This begs the question of whether an ideal mobility scale should encompass both components.

Previous studies of hospital mobility have deployed tools such as Katz Activities of Daily Living (ADLs)9 and the Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB),10 and there is a recent trend toward using the Activity Measure for Post-Acute Care (AM-PAC).11 However, none of these tools, including the one discussed in this review, were designed to capture mobility levels in hospitalized patients. The Katz ADLs and the SPPB were designed for community living adults, and the AM-PAC was designed for a more mobile post-acute-care patient population. Although these tools do have limitations for use with hospitalized patients, they have shown promising results.10,12

What does all this mean for implementation? Do we have enough data on the existing scales to say we should be implementing them—or in the case of Braden, continuing to use them—to measure function and mobility in hospitalized patients? Implementing an ideal mobility assessment tool into the routinized care of the hospital patient may be necessary but insufficient. Complementing the use of these tools with more objective and precise mobility measures (eg, activity counts or steps from wearable sensors) would greatly increase the ability to accurately assess mobility and potentially enable providers to recommend specific mobility goals for patients in the form of steps or minutes of activity per day. In conclusion, the provocative results by Valiani et al.8 underscore the importance of mobility for hospitalized patients but also suggest many opportunities for future research and implementation to improve hospital care, especially for older adults.

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

1. Covinsky KE, Pierluissi E, Johnston CB. Hospitalization-associated disability: “She was probably able to ambulate, but I’m not sure.” JAMA. 2011;306(16):1782-1793. PubMed

2. Greysen SR, Stijacic Cenzer I, Auerbach AD, Covinsky KE. Functional impairment and hospital readmission in Medicare seniors. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(4):559-565. PubMed

3. Covinsky KE, Palmer RM, Fortinsky RH, et al. Loss of independence in activities of daily living in older adults hospitalized with medical illnesses: increased vulnerability with age. J Amer Geriatr Soc. 2003;51(4):451-458. PubMed

4. Barnes DE, Mehta KM, Boscardin WJ, et al. Prediction of recovery, dependence or death in elders who become disabled during hospitalization. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28(2):261-268. PubMed

5. Detsky AS, Krumholz HM. Reducing the trauma of hospitalization. JAMA. 2014;311(21):2169-2170. PubMed

6. Creditor MC. Hazards of hospitalization of the elderly. Ann Intern Med. 1993;118(3):219-223. PubMed

7. Krumholz HM. Post-hospital syndrome—an acquired, transient condition of generalized risk. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(2):100-102. PubMed

8. Valiani V, Chen Z, Lipori G, Pahor M, Sabbá C, Manini TM. Prognostic value of Braden activity subscale for mobility status in hospitalized older adults. J Hosp Med. 2017;12(6):396-401. PubMed

9. Katz S, Ford AB, Moskowitz RW, Jackson BA, Jaffe MW. Studies of illness in the aged. The index of ADL: a standardized measure of biological and psychosocial function. JAMA. 1963;185:914-919. PubMed

10. Guralnik JM, Simonsick EM, Ferrucci L, et al. A short physical performance battery assessing lower extremity function: association with self-reported disability and prediction of mortality and nursing home admission. J Gerontol A Bio Sci Med Sci. 1994;49(2):M85-M94. PubMed

11. Haley SM, Andres PL, Coster WJ, Kosinski M, Ni P, Jette AM. Short-form activity measure for post-acute care. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2004;85(4):649-660. PubMed

12. Wallace M, Shelkey M. Monitoring functional status in hospitalized older adults. Am J Nurs. 2008;108(4):64-71. PubMed

1. Covinsky KE, Pierluissi E, Johnston CB. Hospitalization-associated disability: “She was probably able to ambulate, but I’m not sure.” JAMA. 2011;306(16):1782-1793. PubMed

2. Greysen SR, Stijacic Cenzer I, Auerbach AD, Covinsky KE. Functional impairment and hospital readmission in Medicare seniors. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(4):559-565. PubMed

3. Covinsky KE, Palmer RM, Fortinsky RH, et al. Loss of independence in activities of daily living in older adults hospitalized with medical illnesses: increased vulnerability with age. J Amer Geriatr Soc. 2003;51(4):451-458. PubMed

4. Barnes DE, Mehta KM, Boscardin WJ, et al. Prediction of recovery, dependence or death in elders who become disabled during hospitalization. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28(2):261-268. PubMed

5. Detsky AS, Krumholz HM. Reducing the trauma of hospitalization. JAMA. 2014;311(21):2169-2170. PubMed

6. Creditor MC. Hazards of hospitalization of the elderly. Ann Intern Med. 1993;118(3):219-223. PubMed

7. Krumholz HM. Post-hospital syndrome—an acquired, transient condition of generalized risk. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(2):100-102. PubMed

8. Valiani V, Chen Z, Lipori G, Pahor M, Sabbá C, Manini TM. Prognostic value of Braden activity subscale for mobility status in hospitalized older adults. J Hosp Med. 2017;12(6):396-401. PubMed

9. Katz S, Ford AB, Moskowitz RW, Jackson BA, Jaffe MW. Studies of illness in the aged. The index of ADL: a standardized measure of biological and psychosocial function. JAMA. 1963;185:914-919. PubMed

10. Guralnik JM, Simonsick EM, Ferrucci L, et al. A short physical performance battery assessing lower extremity function: association with self-reported disability and prediction of mortality and nursing home admission. J Gerontol A Bio Sci Med Sci. 1994;49(2):M85-M94. PubMed

11. Haley SM, Andres PL, Coster WJ, Kosinski M, Ni P, Jette AM. Short-form activity measure for post-acute care. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2004;85(4):649-660. PubMed

12. Wallace M, Shelkey M. Monitoring functional status in hospitalized older adults. Am J Nurs. 2008;108(4):64-71. PubMed

© 2017 Society of Hospital Medicine

The Puzzle of Posthospital Recovery

Admission to a hospital for acute care is often a puzzling and traumatic experience for patients.[1, 2] Even after overcoming important hurdles such as receiving the right diagnosis, being treated with appropriate therapies, and experiencing initial improvement, the ultimate goal of complete recovery after discharge remains elusive for many. Dozens of interventions have been tested to reduce failed recoveries and readmissions with mixed results. Most of these have relied on system‐level changes such as improved medication reconciliation and postdischarge phone calls.[3, 4] Physicians have largely been ignored in such efforts. Most systems leave it up to individual physicians to decide how much time and effort to invest in postdischarge care, and patient outcomes are often highly dependent on a physician's skill, interest, and experience.

We are both hospitalists who attend regularly on general internal medicine services in the United States and Canada. In that capacity, we have experienced many successes and failures in helping patients recover after discharge. This Perspective frames the problem of engaging both hospitalists and office‐based physicians in transitions of care within the current context of readmission reduction efforts, and proposes a more structured approach for integrating those physicians into postdischarge care to promote recovery. Although we also consider broader policy efforts to reduce fragmentation and misaligned incentives such as electronic health records (EHRs), accountable care organizations (ACOs), and the patient‐centered medical home (PCMH), our focus is on how these may (or may not) help front‐line physicians to solve the puzzle of posthospital recovery in the current state of affairs.

THE PROBLEMLACK OF TIME, VARIABLE ENGAGEMENT, SILOED COMMUNICATION

Perhaps the most important barrier to engaging physicians in the posthospital recovery phase is their limited time and energy. Today's rapid throughput and the complexity of acute care leave little bandwidth for issues that are not right in front of hospitalists. Once discharged, patients are often out of sight, out of mind.[5] Office‐based physicians face similar time constraints.[6] In both settings, physicians find themselves operating in silos with significant communication barriers that are time consuming and difficult to overcome.

There are many current policy efforts to break down these silos, a prominent example being recent incentives to speed the widespread use of EHRs. Although EHR implementation progress has been steady, nearly half of US hospitals still do not have a basic EHR, and more advanced functions required for sharing care summaries and allowing patients to access their EHR are not in place at most hospitals that have implemented basic EHRs already.[7] Furthermore, the state of implementation in office‐based settings lags even farther behind hospitals.[8] Finally, our personal experience working in systems with fully integrated EHR systems has suggested to us that sometimes more shared information simply becomes part of the problem, as it is far too easy to include too many complex details of hospitalization in discharge summaries.

Moreover, as front‐line hospitalists, we generally want to help with transitional issues that occur after patients have left our hospital, and we are very mindful of the tradition of the physician who takes responsibility for all aspects of their patients' care in all settings. Yet this tradition may be more representative of the 20th century ideal of continuity than the new continuity that we see emerging in the 21st century.[9] Thus, the question at hand now is how individual physicians should prioritize and execute these tasks without overreaching.

EFFECTS OF THE PROBLEM IN PRACTICEVARIATIONS IN PHYSICIAN ENGAGEMENT

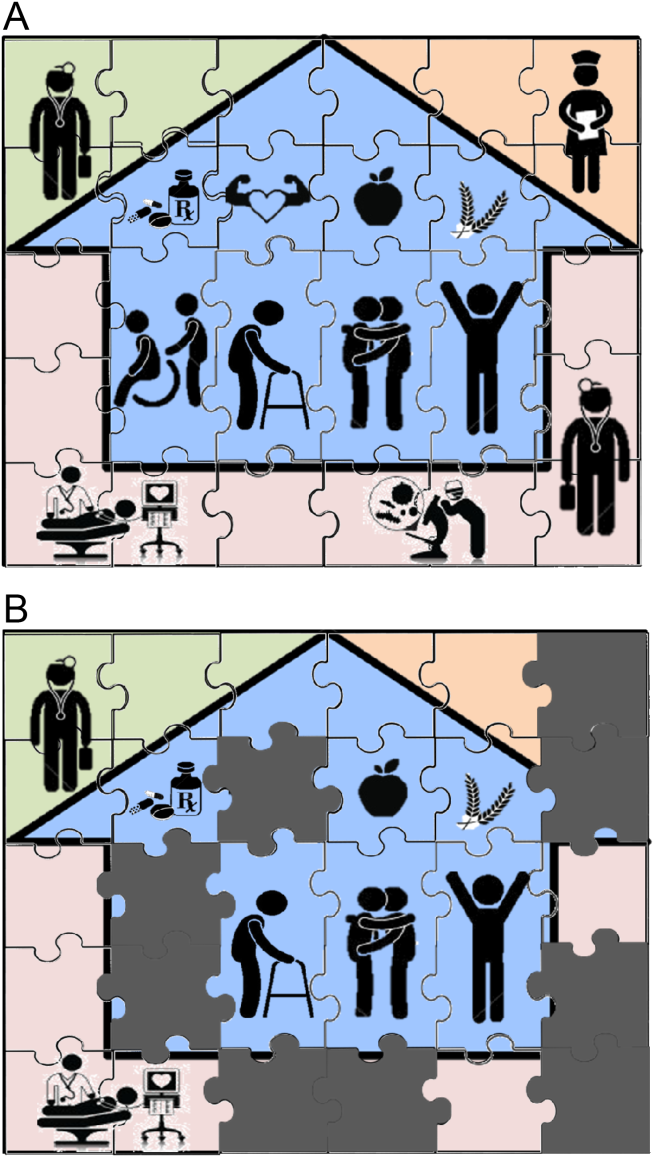

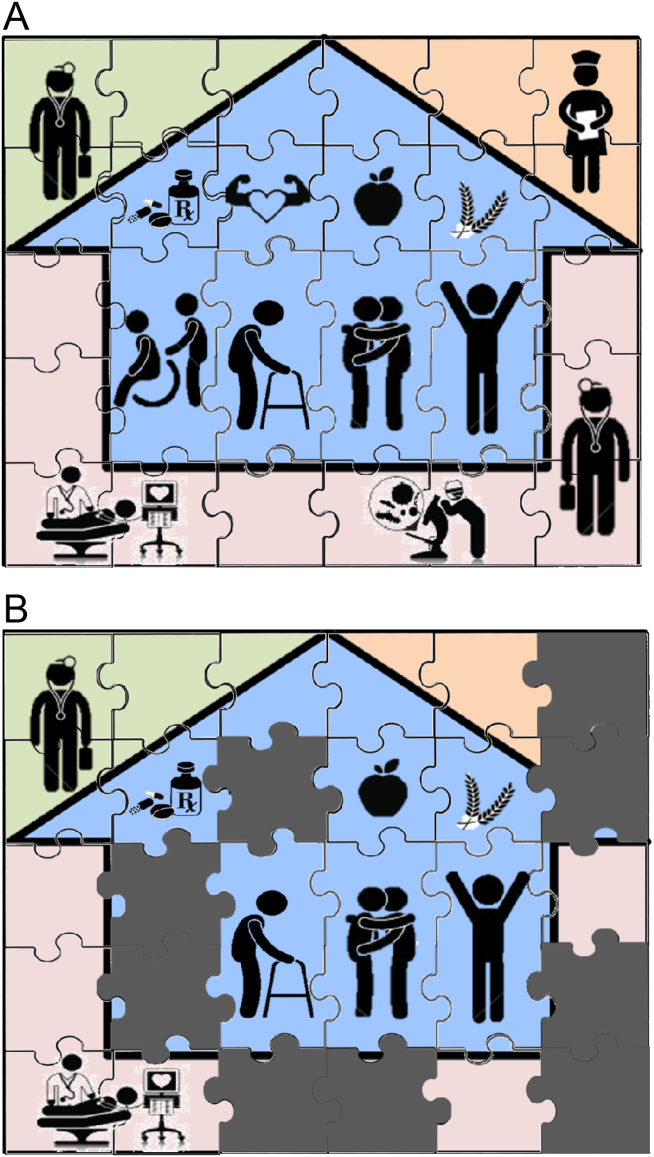

Patient needs after discharge are not uniform, and risk prediction is still imprecise despite many studies.[10] Some patients need no help; others need only targeted help with specific gaps; still others need full‐time navigators to meaningfully reduce their risk of ending up back in the emergency department.[11] The goal is to piece together the resources required to create a complete picture of patient support; much like the way ones solves a jigsaw puzzle (Figure 1A). Despite best efforts, the gaps in careor missing pieces[12]may only become apparent after discharge. Recent research suggests physicians do not see the same gaps as patients do and agree on causes for readmission less than 50% of the time.[13, 14] Often, these gaps come to light when an outside pharmacist, home health nurse, or case manager reaches out to the hospital or primary care physician to address a new problem (Figure 1B). As frequent recipients of those calls for help, we are conflicted in our reaction. On the one hand, we want to know when our carefully crafted plans fall apart. On the other hand, neither of us looks forward to voice mail messages informing us that the specialist to whom we referred the patient for follow‐up never called with an appointment. Micromanaging this kind of care can be very frustrating, both when we are the first person called or resource of last resort.

Even when physicians do not feel burdened by postdischarge care, they may be ineffective due to a lack of experience or resources. These efforts can leave them feeling demoralized, which in turn may further discourage them from future engagement, solidifying a pattern of missing (or perhaps lost) pieces (Figure 1B). Too often, a well‐intentioned but underpowered effort becomes a solution crushed by the weight of the problem. Successful physician models for care coordination must balance competing ideals of the 1 doctor, 1 patient strategy that preserve continuity,[15] with the need to focus individual physicians' time on those postdischarge tasks in which their engagement is clearly needed.