User login

Mobility assessment in the hospital: What are the “next steps”?

Mobility impairment (reduced ability to change body position or ambulate) is common among older adults during hospitalization1 and is correlated with higher rates of readmission,2 long-term care placement,3 and even death.4 Although some may perceive mobility impairment during hospitalization as a temporary inconvenience, recent research suggests disruptions of basic activities of daily life such as mobility may be “traumatic” 5 or “toxic”6 to older adults with long-term post-hospital effects.7 While these studies highlight the underestimated effects of low mobility during hospitalization, they are based on data collected for research purposes using mobility measurement tools not typically utilized in routine hospital care.

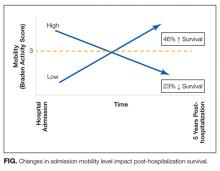

The absence of a standardized mobility measurement tool used as part of routine hospital care poses a barrier to estimating the effects of low hospital mobility and programs seeking to improve mobility levels in hospitalized patients. In this issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine, Valiani et al.8 found a novel approach to measure mobility using a universally disseminated clinical scale (Braden). Using the activity subscale of the Braden scale, the authors found that mobility level changes during hospitalization can have a striking impact on post-discharge mortality. Their results indicate that older adults who develop mobility impairment during hospitalization had higher odds of death, specifically 1.23 times greater risk, within 6 months after discharge (23% decreased chance of survival). Most of the risk applies in the first 30 days and remains to a lesser extent for up to 5 years post-hospitalization. An equally interesting finding was that those who enter the hospital with low mobility but improve have a 46% higher survival rate. Again, most of the benefit is seen during hospitalization or immediately afterward, but the benefit persists for up to 5 years. A schematic of the results are presented in the Figure. Notably, Valiani et al.8 did not find regression to the mean Braden score of 3.

This novel use of the Braden activity subscale raises a question: Should we be using the Braden activity component to measure mobility in the hospital? Put another way, what scale should we be using in the hospital? Using the Braden activity subscale is convenient, since it capitalizes on data already being gathered. However, this subscale focuses solely on ambulation frequency; it doesn’t capture other mobility domains, such as ability to change body position. Ambulation is only half of the mobility story. It is interesting that although the Braden scale does have a mobility subscale that captures body position changes, the authors chose not to use it. This begs the question of whether an ideal mobility scale should encompass both components.

Previous studies of hospital mobility have deployed tools such as Katz Activities of Daily Living (ADLs)9 and the Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB),10 and there is a recent trend toward using the Activity Measure for Post-Acute Care (AM-PAC).11 However, none of these tools, including the one discussed in this review, were designed to capture mobility levels in hospitalized patients. The Katz ADLs and the SPPB were designed for community living adults, and the AM-PAC was designed for a more mobile post-acute-care patient population. Although these tools do have limitations for use with hospitalized patients, they have shown promising results.10,12

What does all this mean for implementation? Do we have enough data on the existing scales to say we should be implementing them—or in the case of Braden, continuing to use them—to measure function and mobility in hospitalized patients? Implementing an ideal mobility assessment tool into the routinized care of the hospital patient may be necessary but insufficient. Complementing the use of these tools with more objective and precise mobility measures (eg, activity counts or steps from wearable sensors) would greatly increase the ability to accurately assess mobility and potentially enable providers to recommend specific mobility goals for patients in the form of steps or minutes of activity per day. In conclusion, the provocative results by Valiani et al.8 underscore the importance of mobility for hospitalized patients but also suggest many opportunities for future research and implementation to improve hospital care, especially for older adults.

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

1. Covinsky KE, Pierluissi E, Johnston CB. Hospitalization-associated disability: “She was probably able to ambulate, but I’m not sure.” JAMA. 2011;306(16):1782-1793. PubMed

2. Greysen SR, Stijacic Cenzer I, Auerbach AD, Covinsky KE. Functional impairment and hospital readmission in Medicare seniors. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(4):559-565. PubMed

3. Covinsky KE, Palmer RM, Fortinsky RH, et al. Loss of independence in activities of daily living in older adults hospitalized with medical illnesses: increased vulnerability with age. J Amer Geriatr Soc. 2003;51(4):451-458. PubMed

4. Barnes DE, Mehta KM, Boscardin WJ, et al. Prediction of recovery, dependence or death in elders who become disabled during hospitalization. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28(2):261-268. PubMed

5. Detsky AS, Krumholz HM. Reducing the trauma of hospitalization. JAMA. 2014;311(21):2169-2170. PubMed

6. Creditor MC. Hazards of hospitalization of the elderly. Ann Intern Med. 1993;118(3):219-223. PubMed

7. Krumholz HM. Post-hospital syndrome—an acquired, transient condition of generalized risk. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(2):100-102. PubMed

8. Valiani V, Chen Z, Lipori G, Pahor M, Sabbá C, Manini TM. Prognostic value of Braden activity subscale for mobility status in hospitalized older adults. J Hosp Med. 2017;12(6):396-401. PubMed

9. Katz S, Ford AB, Moskowitz RW, Jackson BA, Jaffe MW. Studies of illness in the aged. The index of ADL: a standardized measure of biological and psychosocial function. JAMA. 1963;185:914-919. PubMed

10. Guralnik JM, Simonsick EM, Ferrucci L, et al. A short physical performance battery assessing lower extremity function: association with self-reported disability and prediction of mortality and nursing home admission. J Gerontol A Bio Sci Med Sci. 1994;49(2):M85-M94. PubMed

11. Haley SM, Andres PL, Coster WJ, Kosinski M, Ni P, Jette AM. Short-form activity measure for post-acute care. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2004;85(4):649-660. PubMed

12. Wallace M, Shelkey M. Monitoring functional status in hospitalized older adults. Am J Nurs. 2008;108(4):64-71. PubMed

Mobility impairment (reduced ability to change body position or ambulate) is common among older adults during hospitalization1 and is correlated with higher rates of readmission,2 long-term care placement,3 and even death.4 Although some may perceive mobility impairment during hospitalization as a temporary inconvenience, recent research suggests disruptions of basic activities of daily life such as mobility may be “traumatic” 5 or “toxic”6 to older adults with long-term post-hospital effects.7 While these studies highlight the underestimated effects of low mobility during hospitalization, they are based on data collected for research purposes using mobility measurement tools not typically utilized in routine hospital care.

The absence of a standardized mobility measurement tool used as part of routine hospital care poses a barrier to estimating the effects of low hospital mobility and programs seeking to improve mobility levels in hospitalized patients. In this issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine, Valiani et al.8 found a novel approach to measure mobility using a universally disseminated clinical scale (Braden). Using the activity subscale of the Braden scale, the authors found that mobility level changes during hospitalization can have a striking impact on post-discharge mortality. Their results indicate that older adults who develop mobility impairment during hospitalization had higher odds of death, specifically 1.23 times greater risk, within 6 months after discharge (23% decreased chance of survival). Most of the risk applies in the first 30 days and remains to a lesser extent for up to 5 years post-hospitalization. An equally interesting finding was that those who enter the hospital with low mobility but improve have a 46% higher survival rate. Again, most of the benefit is seen during hospitalization or immediately afterward, but the benefit persists for up to 5 years. A schematic of the results are presented in the Figure. Notably, Valiani et al.8 did not find regression to the mean Braden score of 3.

This novel use of the Braden activity subscale raises a question: Should we be using the Braden activity component to measure mobility in the hospital? Put another way, what scale should we be using in the hospital? Using the Braden activity subscale is convenient, since it capitalizes on data already being gathered. However, this subscale focuses solely on ambulation frequency; it doesn’t capture other mobility domains, such as ability to change body position. Ambulation is only half of the mobility story. It is interesting that although the Braden scale does have a mobility subscale that captures body position changes, the authors chose not to use it. This begs the question of whether an ideal mobility scale should encompass both components.

Previous studies of hospital mobility have deployed tools such as Katz Activities of Daily Living (ADLs)9 and the Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB),10 and there is a recent trend toward using the Activity Measure for Post-Acute Care (AM-PAC).11 However, none of these tools, including the one discussed in this review, were designed to capture mobility levels in hospitalized patients. The Katz ADLs and the SPPB were designed for community living adults, and the AM-PAC was designed for a more mobile post-acute-care patient population. Although these tools do have limitations for use with hospitalized patients, they have shown promising results.10,12

What does all this mean for implementation? Do we have enough data on the existing scales to say we should be implementing them—or in the case of Braden, continuing to use them—to measure function and mobility in hospitalized patients? Implementing an ideal mobility assessment tool into the routinized care of the hospital patient may be necessary but insufficient. Complementing the use of these tools with more objective and precise mobility measures (eg, activity counts or steps from wearable sensors) would greatly increase the ability to accurately assess mobility and potentially enable providers to recommend specific mobility goals for patients in the form of steps or minutes of activity per day. In conclusion, the provocative results by Valiani et al.8 underscore the importance of mobility for hospitalized patients but also suggest many opportunities for future research and implementation to improve hospital care, especially for older adults.

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

Mobility impairment (reduced ability to change body position or ambulate) is common among older adults during hospitalization1 and is correlated with higher rates of readmission,2 long-term care placement,3 and even death.4 Although some may perceive mobility impairment during hospitalization as a temporary inconvenience, recent research suggests disruptions of basic activities of daily life such as mobility may be “traumatic” 5 or “toxic”6 to older adults with long-term post-hospital effects.7 While these studies highlight the underestimated effects of low mobility during hospitalization, they are based on data collected for research purposes using mobility measurement tools not typically utilized in routine hospital care.

The absence of a standardized mobility measurement tool used as part of routine hospital care poses a barrier to estimating the effects of low hospital mobility and programs seeking to improve mobility levels in hospitalized patients. In this issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine, Valiani et al.8 found a novel approach to measure mobility using a universally disseminated clinical scale (Braden). Using the activity subscale of the Braden scale, the authors found that mobility level changes during hospitalization can have a striking impact on post-discharge mortality. Their results indicate that older adults who develop mobility impairment during hospitalization had higher odds of death, specifically 1.23 times greater risk, within 6 months after discharge (23% decreased chance of survival). Most of the risk applies in the first 30 days and remains to a lesser extent for up to 5 years post-hospitalization. An equally interesting finding was that those who enter the hospital with low mobility but improve have a 46% higher survival rate. Again, most of the benefit is seen during hospitalization or immediately afterward, but the benefit persists for up to 5 years. A schematic of the results are presented in the Figure. Notably, Valiani et al.8 did not find regression to the mean Braden score of 3.

This novel use of the Braden activity subscale raises a question: Should we be using the Braden activity component to measure mobility in the hospital? Put another way, what scale should we be using in the hospital? Using the Braden activity subscale is convenient, since it capitalizes on data already being gathered. However, this subscale focuses solely on ambulation frequency; it doesn’t capture other mobility domains, such as ability to change body position. Ambulation is only half of the mobility story. It is interesting that although the Braden scale does have a mobility subscale that captures body position changes, the authors chose not to use it. This begs the question of whether an ideal mobility scale should encompass both components.

Previous studies of hospital mobility have deployed tools such as Katz Activities of Daily Living (ADLs)9 and the Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB),10 and there is a recent trend toward using the Activity Measure for Post-Acute Care (AM-PAC).11 However, none of these tools, including the one discussed in this review, were designed to capture mobility levels in hospitalized patients. The Katz ADLs and the SPPB were designed for community living adults, and the AM-PAC was designed for a more mobile post-acute-care patient population. Although these tools do have limitations for use with hospitalized patients, they have shown promising results.10,12

What does all this mean for implementation? Do we have enough data on the existing scales to say we should be implementing them—or in the case of Braden, continuing to use them—to measure function and mobility in hospitalized patients? Implementing an ideal mobility assessment tool into the routinized care of the hospital patient may be necessary but insufficient. Complementing the use of these tools with more objective and precise mobility measures (eg, activity counts or steps from wearable sensors) would greatly increase the ability to accurately assess mobility and potentially enable providers to recommend specific mobility goals for patients in the form of steps or minutes of activity per day. In conclusion, the provocative results by Valiani et al.8 underscore the importance of mobility for hospitalized patients but also suggest many opportunities for future research and implementation to improve hospital care, especially for older adults.

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

1. Covinsky KE, Pierluissi E, Johnston CB. Hospitalization-associated disability: “She was probably able to ambulate, but I’m not sure.” JAMA. 2011;306(16):1782-1793. PubMed

2. Greysen SR, Stijacic Cenzer I, Auerbach AD, Covinsky KE. Functional impairment and hospital readmission in Medicare seniors. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(4):559-565. PubMed

3. Covinsky KE, Palmer RM, Fortinsky RH, et al. Loss of independence in activities of daily living in older adults hospitalized with medical illnesses: increased vulnerability with age. J Amer Geriatr Soc. 2003;51(4):451-458. PubMed

4. Barnes DE, Mehta KM, Boscardin WJ, et al. Prediction of recovery, dependence or death in elders who become disabled during hospitalization. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28(2):261-268. PubMed

5. Detsky AS, Krumholz HM. Reducing the trauma of hospitalization. JAMA. 2014;311(21):2169-2170. PubMed

6. Creditor MC. Hazards of hospitalization of the elderly. Ann Intern Med. 1993;118(3):219-223. PubMed

7. Krumholz HM. Post-hospital syndrome—an acquired, transient condition of generalized risk. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(2):100-102. PubMed

8. Valiani V, Chen Z, Lipori G, Pahor M, Sabbá C, Manini TM. Prognostic value of Braden activity subscale for mobility status in hospitalized older adults. J Hosp Med. 2017;12(6):396-401. PubMed

9. Katz S, Ford AB, Moskowitz RW, Jackson BA, Jaffe MW. Studies of illness in the aged. The index of ADL: a standardized measure of biological and psychosocial function. JAMA. 1963;185:914-919. PubMed

10. Guralnik JM, Simonsick EM, Ferrucci L, et al. A short physical performance battery assessing lower extremity function: association with self-reported disability and prediction of mortality and nursing home admission. J Gerontol A Bio Sci Med Sci. 1994;49(2):M85-M94. PubMed

11. Haley SM, Andres PL, Coster WJ, Kosinski M, Ni P, Jette AM. Short-form activity measure for post-acute care. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2004;85(4):649-660. PubMed

12. Wallace M, Shelkey M. Monitoring functional status in hospitalized older adults. Am J Nurs. 2008;108(4):64-71. PubMed

1. Covinsky KE, Pierluissi E, Johnston CB. Hospitalization-associated disability: “She was probably able to ambulate, but I’m not sure.” JAMA. 2011;306(16):1782-1793. PubMed

2. Greysen SR, Stijacic Cenzer I, Auerbach AD, Covinsky KE. Functional impairment and hospital readmission in Medicare seniors. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(4):559-565. PubMed

3. Covinsky KE, Palmer RM, Fortinsky RH, et al. Loss of independence in activities of daily living in older adults hospitalized with medical illnesses: increased vulnerability with age. J Amer Geriatr Soc. 2003;51(4):451-458. PubMed

4. Barnes DE, Mehta KM, Boscardin WJ, et al. Prediction of recovery, dependence or death in elders who become disabled during hospitalization. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28(2):261-268. PubMed

5. Detsky AS, Krumholz HM. Reducing the trauma of hospitalization. JAMA. 2014;311(21):2169-2170. PubMed

6. Creditor MC. Hazards of hospitalization of the elderly. Ann Intern Med. 1993;118(3):219-223. PubMed

7. Krumholz HM. Post-hospital syndrome—an acquired, transient condition of generalized risk. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(2):100-102. PubMed

8. Valiani V, Chen Z, Lipori G, Pahor M, Sabbá C, Manini TM. Prognostic value of Braden activity subscale for mobility status in hospitalized older adults. J Hosp Med. 2017;12(6):396-401. PubMed

9. Katz S, Ford AB, Moskowitz RW, Jackson BA, Jaffe MW. Studies of illness in the aged. The index of ADL: a standardized measure of biological and psychosocial function. JAMA. 1963;185:914-919. PubMed

10. Guralnik JM, Simonsick EM, Ferrucci L, et al. A short physical performance battery assessing lower extremity function: association with self-reported disability and prediction of mortality and nursing home admission. J Gerontol A Bio Sci Med Sci. 1994;49(2):M85-M94. PubMed

11. Haley SM, Andres PL, Coster WJ, Kosinski M, Ni P, Jette AM. Short-form activity measure for post-acute care. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2004;85(4):649-660. PubMed

12. Wallace M, Shelkey M. Monitoring functional status in hospitalized older adults. Am J Nurs. 2008;108(4):64-71. PubMed

© 2017 Society of Hospital Medicine