Case Report

A 63-year-old man was evaluated in the Mohs clinic for a lesion on the right supraclavicular neck, which he described as a linear asymptomatic “birthmark” that had been present since childhood and stable for many years. It began to enlarge approximately 5 years prior, became increasingly red, and had occasional crusting. The lesion also gradually became more irritated with repeated mild trauma when he carried a backpack while hiking. On physical examination, a 10×2-cm, linear, pink plaque with an irregular border, translucent rolled edges, and central smooth atrophic skin was seen on the right supraclavicular neck (Figure). There was no visible epidermal nevus or nevus sebaceous in the area. A shave biopsy of the lesion confirmed the pathologic diagnosis of basal cell carcinoma, nodular type, along with the morphologic diagnosis of linear basal cell carcinoma (LBCC). The tumor was completely removed with standard excision using 5-mm margins.

Approximately 10 months after the original excision, the patient developed an irritated erosion that occasionally bled when his backpack rubbed against it. He returned to the clinic after the erosion failed to heal. Physical examination revealed a 1.4×0.7-cm, eroded, pink papule with large telangiectases at the superior pole of the excision scar. A shave biopsy confirmed the diagnosis of a recurrent infiltrative basal cell carcinoma. The tumor was then completely excised using Mohs micrographic surgery.

Comment

Linear basal cell carcinoma, first described by Lewis1 in 1985, is a rare morphologic variant of basal cell carcinoma. In 2011, Al-Niaimi and Lyon2 performed a comprehensive literature search on LBCC (1985-2008) and found only 39 cases (including 2 of their own) had been published since the pioneer case in 1985. It was determined that the most common sites affected were the periorbital area and neck (n=13 each [67%]), and the majority were histologically nodular (n=27 [69%]). Mohs micrographic surgery was the most common treatment method (n=23 [59%]), followed by primary excision (n=17 [44%]). A history of trauma, radiotherapy, or prior operation in association with the site of the LBCC was discovered in only 7 cases (18%).2 Although Peschen et al3 proposed that trauma—both physical and surgical—and radiotherapy may play a role in the development of LBCCs, the low incidence reported suggests that other factors may be involved. To determine if genetic factors were contributing to the development of LBCCs, Yamaguchi et al4 investigated the expression of p27 and PCTAIRE1, both known to contribute to tumorigenesis when mutated, as well as somatic gene mutations using deep sequencing in a case of LBCC; they found no associated genetic mutation.

Reported Cases of LBCC

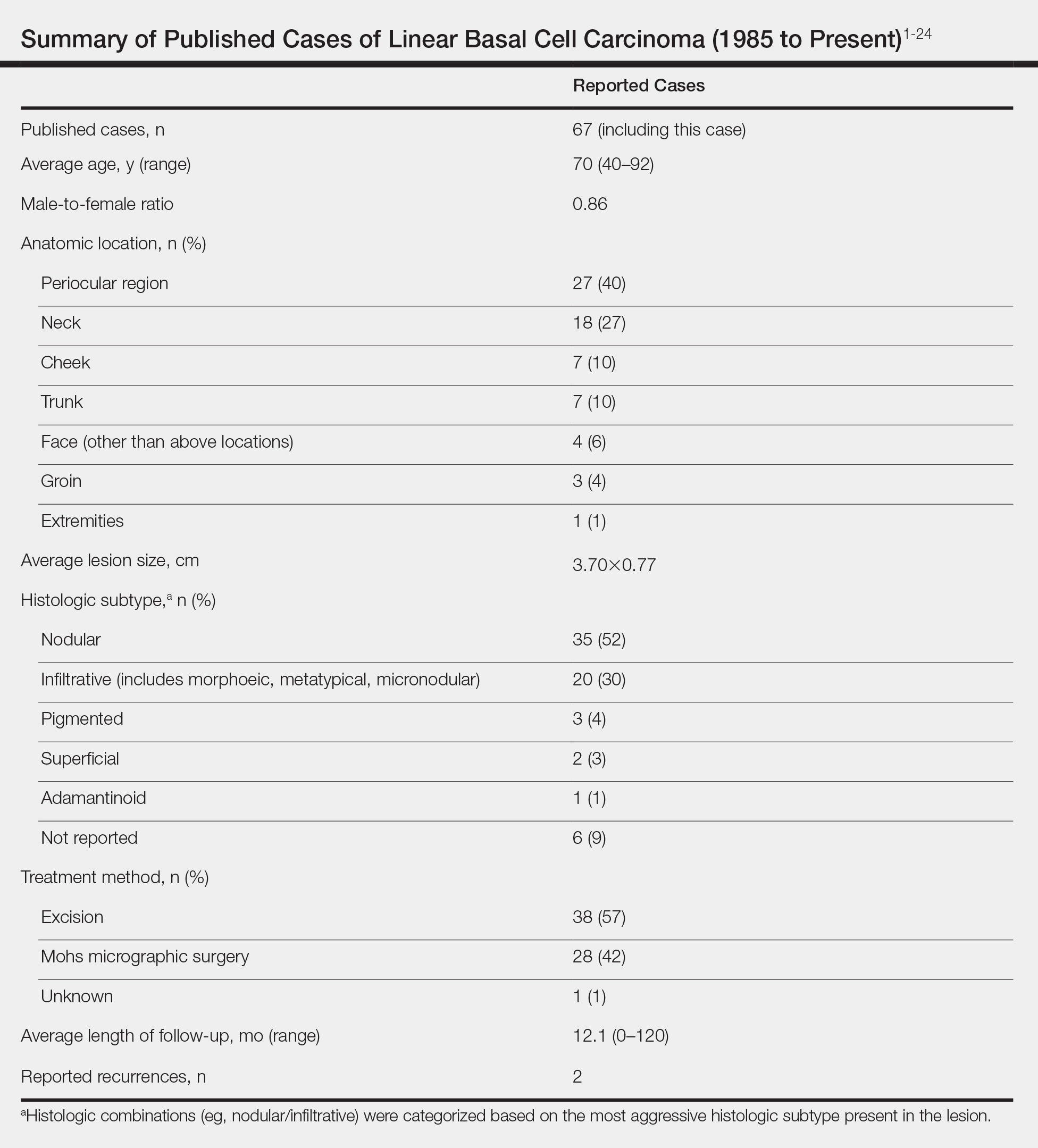

According to a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms linear and basal cell carcinoma, 67 cases (including the current case) of LBCC have been published since 1985. The patient demographics, anatomic location, histologic subtype, treatment methods, and frequency of recurrence for all reported cases of LBCC are summarized in the Table.1-24 There were 36 women and 31 men, with an average age of 70 years (range, 40–92 years). The most commonly affected sites were the periocular region (n=27) and neck (n=18). Histologically, most LBCCs were nodular (n=35), with the next most common histologic subtype being infiltrative (n=20), which included the morphoeic, metatypical, and micronodular subtypes under the overarching infiltrative subtype. The most frequently chosen treatment option was primary excision (n=38 [57%]), followed by Mohs micrographic surgery (n=28 [42%]). Risk factors previously identified by Al-Niaimi and Lyon,2 including trauma, radiotherapy, or prior operation, were reported in 12 of 67 cases. Recurrence was reported in only 2 of 67 cases, 1 being the current case; however, an accurate recurrence rate could not be calculated due to lack of follow-up or short length of follow-up in most of the reported cases.

Presentation and Treatment

Currently, there are no set criteria for the diagnosis of LBCC, but it has been shown to follow a characteristic morphologic pattern, favoring extension in one direction leading to a length-to-width ratio that typically is at least 3 to 1.5 With most lesions presenting in the periocular region along relaxed skin tension lines, it has been speculated that these tumors expand along wrinkles.2 Pierard and Lapiere25 proposed that the preferential parallel orientation and a straightening of thin collagen bundles and elastic fibers within the reticular dermis combined with relaxed skin tension lines and muscle contraction perpendicular to these stromal parts may influence the growth of tumors preferentially in one direction, contributing to linearity of the lesion. In addition, the clinical appearance is not a reliable indicator of subclinical extension.2 Therefore, Lim et al6 recommended Mohs micrographic surgery as the best initial treatment of LBCCs.

Conclusion

Linear basal cell carcinoma should be considered a distinct morphologic variant of basal cell carcinoma. Although likely underreported, this variant is uncommon. It presents most often in the periocular and neck regions. The most common histologic subtypes are nodular and infiltrative. Because of the likelihood of subclinical spread, LBCC should be regarded as a high-risk subtype. As such, Mohs micrographic surgery or excision with complete circumferential peripheral and deep margin assessment is recommended as first-line treatment of LBCC.6