User login

As humans live longer, a renewed focus on quality of life has made the prompt diagnosis and treatment of sleep-related disorders in older adults increasingly necessary.1 Normative aging results in multiple changes in sleep architecture, including decreased total sleep time, decreased sleep efficiency, decreased slow-wave sleep (SWS), and increased awakenings after sleep onset.2 Sleep disturbances in older adults are increasingly recognized as multifactorial health conditions requiring comprehensive modification of risk factors, diagnosis, and treatment.3

In this article, we discuss the effects of aging on sleep architecture and provide an overview of primary sleep disorders in older adults. We also summarize strategies for diagnosing and treating sleep disorders in these patients.

Elements of the sleep cycle

The human sleep cycle begins with light sleep (sleep stages 1 and 2), progresses into SWS (sleep stage 3), and culminates in rapid eye movement (REM) sleep. The first 3 stages are referred to as non-rapid eye movement sleep (NREM). Throughout the night, this coupling of NREM and REM cycles occurs 4 to 6 times, with each successive cycle decreasing in length until awakening.4

Two complex neurologic pathways intersect to regulate the timing of sleep and wakefulness on arousal. The first pathway, the circadian system, is located within the suprachiasmatic nucleus of the hypothalamus and is highly dependent on external stimuli (light, food, etc.) to synchronize sleep/wake cycles. The suprachiasmatic nucleus regulates melatonin secretion by the pineal gland, which signals day-night transitions. The other pathway, the homeostatic system, modifies the amount of sleep needed daily. When multiple days of poor sleep occur, homeostatic sleep pressure (colloquially described as sleep debt) compensates by increasing the amount of sleep required in the following days. Together, the circadian and homeostatic systems work in conjunction to regulate sleep quantity to approximately one-third of the total sleep-wake cycle.2,5

Age-related dysfunction of the regulatory sleep pathways leads to blunting of the ability to initiate and sustain high-quality sleep.6 Dysregulation of homeostatic sleep pressure decreases time spent in SWS, and failure of the circadian signaling apparatus results in delays in sleep/wake timing.2 While research into the underlying neurobiology of sleep reveals that some of these changes are inherent to aging (Box7-14), significant underdiagnosed pathologies may adversely affect sleep architecture, including polypharmacy, comorbid neuropathology (eg, synucleinopathies, tauopathies, etc.), and primary sleep disorders (insomnias, hypersomnias, and parasomnias).15

Box

It has long been known that sleep architecture changes significantly with age. One of the largest meta-analyses of sleep changes in healthy individuals throughout childhood into old age found that total sleep time, sleep efficiency, percentage of slow-wave sleep, percentage of rapid eye movement sleep (REM), and REM latency all decreased with normative aging.7 Other studies have also found a decreased ability to maintain sleep (increased frequency of awakenings and prolonged nocturnal awakenings).8

Based on several meta-analyses, the average total sleep time at night in the adult population decreases by approximately 10 minutes per decade in both men and women.7,9-11 However, this pattern is not observed after age 60, when the total sleep time plateaus.7 Similarly, the duration of wake after sleep onset increases by approximately 10 minutes every decade for adults age 30 to 60, and plateaus after that.7,8

Epidemiologic studies have suggested that the prevalence of daytime napping increases with age.8 This trend continues into older age without a noticeable plateau.

A study of a nationally representative sample of >7,000 Japanese participants found that a significantly higher proportion of older adults take daytime naps (27.4%) compared with middle-age adults (14.4%).12 Older adults nap more frequently because of both lifestyle and biologic changes that accompany normative aging. Polls in the United States have shown a correlation between frequent napping and an increase in excessive daytime sleepiness, depression, pain, and nocturia.13

While sleep latency steadily increases after age 50, recent studies have shown that in healthy individuals, these changes are modest at best,7,9,14 which suggests that other pathologic factors may be contributing to this problem. Although healthy older people were found to have more frequent arousals throughout the night, they retained the ability to reinitiate sleep as rapidly as younger adults.7,9

Primary sleep disorders

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is one of the most common, yet frequently underdiagnosed reversible causes of sleep disturbances. It is characterized by partial or complete airway obstruction culminating in periods of involuntary cessation of respirations during sleep. The resultant fragmentation in sleep leads to significant downstream effects over time, including excessive daytime sleepiness and fatigue, poor occupational and social performance, and substantial cognitive impairment.3 While it is well known that OSA increases in prevalence throughout middle age, this relationship plateaus after age 60.16 An estimated 40% to 60% of Americans age >60 are affected by OSA.17 The hypoxemia and fragmented sleep caused by unrecognized OSA are associated with a significant decline in activities of daily living (ADL).18 Untreated OSA is strongly linked to the development and progression of several major health conditions, including cardiovascular disease, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, stroke, and depression.19 In studies of long-term care facility residents—many of whom may have comorbid cognitive decline—researchers found that unrecognized OSA often mimics the progressive cognitive decline seen in major neurocognitive disorders.20 However, classic symptoms of OSA may not always be present in these patients, and their daytime sleepiness is often attributed to old age rather than to a pathological etiology.16 Screening for OSA and prompt initiation of the appropriate treatment may reverse OSA-induced cognitive changes in these patients.21

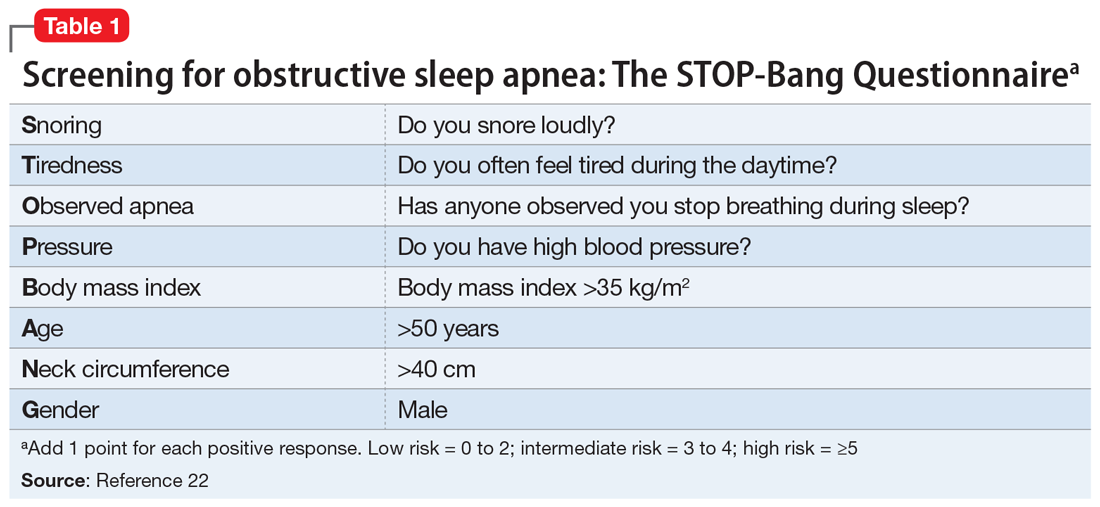

The primary presenting symptom of OSA is snoring, which is correlated with pauses in breathing. Risk factors include increased body mass index (BMI), thick neck circumference, male sex, and advanced age. In older adults, BMI has a lower impact on the Apnea-Hypopnea Index, an indicator of the number of pauses in breathing per hour, when compared with young and middle-age adults.16 Validated screening questionnaires for OSA include the STOP-Bang Questionnaire (Table 122), OSA50, Berlin Questionnaire, and Epworth Sleepiness Scale, each of which is used in different subpopulations. The current diagnostic standard for OSA is nocturnal polysomnography in a sleep laboratory, but recent advances in home sleep apnea testing have made it a viable, low-cost alternative for patients who do not have significant medical comorbidities.23 Standard utilized cutoffs for diagnosis are ≥5 events/hour (hypopneas associated with at least 4% oxygen desaturations) in conjunction with clinical symptoms of OSA.24

Continue to: Treatment

Treatment. First-line treatment for OSA is continuous positive airway pressure therapy, but adherence rates vary widely with patient education and regular follow-up.25 Adjunctive therapy includes weight loss, oral appliances, and uvulopalatopharyngoplasty, a procedure in which tissue in the throat is remodeled or removed.

Central sleep apnea (CSA) is a pause in breathing without evidence of associated respiratory effort. In adults, the development of CSA is indicative of underlying lower brainstem dysfunction, due to intermittent failures in the pontomedullary centers responsible for regulation of rhythmic breathing.26 This can occur as a consequence of multiple diseases, including congestive heart failure, stroke, renal failure, chronic medication use (opioids), and brain tumors.

The Sleep Heart Health Study—the largest community-based cohort study to date examining CSA—estimated that the prevalence of CSA among adults age >65 was 1.1% (compared with 0.4% in those age <65).27 Subgroup analysis revealed that men had significantly higher rates of CSA compared with women (2.7% vs 0.2%, respectively).

CSA may present similarly to OSA (excessive daytime somnolence, insomnia, poor sleep quality, difficulties with attention and concentration). Symptoms may also mimic those of coexisting medical conditions in older adults, such as nocturnal angina or paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea.27 Any older patient with daytime sleepiness and risk factors for CSA should be referred for in-laboratory nocturnal polysomnography, the gold standard diagnostic test. Unlike in OSA, ambulatory diagnostic measures (home sleep apnea testing) have not been validated for this disorder.27

Treatment. The primary treatment for CSA is to address the underlying medical problem. Positive pressure ventilation has been attempted with mixed results. Supplemental oxygen and medical management (acetazolamide or theophylline) can help stimulate breathing. Newer studies have shown favorable outcomes with transvenous neurostimulation or adaptive servoventilation.28-30

Continue to: Insomnia

Insomnia. For a primary diagnosis of insomnia, DSM-5 requires at least 3 nights per week of sleep disturbances that induce distress or functional impairment for at least 3 months.31 The International Classification of Disease, 10th Edition requires at least 1 month of symptoms (lying awake for a long time before falling asleep, sleeping for short periods, being awake for most of the night, feeling lack of sleep, waking up early) after ruling out other sleep disorders, substance use, or other medical conditions.4 Clinically, insomnia tends to present in older adults as a subjective complaint of dissatisfaction with the quality and/or quantity of their sleep. Insomnia has been consistently shown to be a significant risk factor for both the development or exacerbation of depression in older adults.32-34

While the diagnosis of insomnia is mainly clinical via a thorough sleep and medication history, assistive ancillary testing can include wrist actigraphy and screening questionnaires (the Insomnia Severity Index and the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index).4 Because population studies of older adults have found discrepancies between objective and subjective methods of assessing sleep quality, relying on the accuracy of self-reported symptoms alone is questionable.35

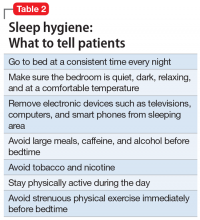

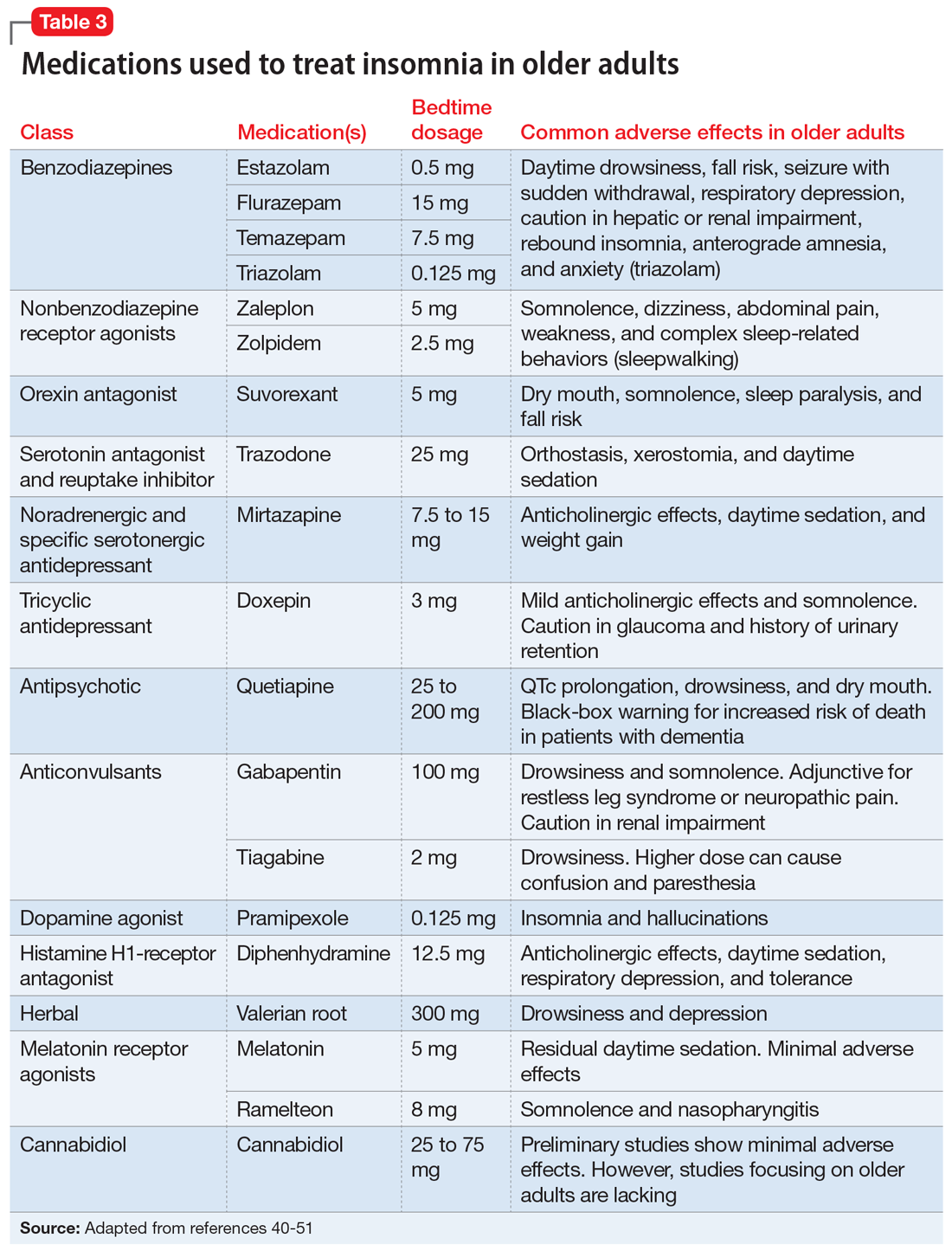

Treatment. Given that drug elimination half-life increases with age, and the risks of adverse effects are increased in older adults, the preferred treatment modalities for insomnia are nonpharmacologic.4 Sleep hygiene education (Table 2) and cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) for insomnia are often the first-line therapies.4,36,37 It is crucial to manage comorbidities such as heart disease and obesity, as well as sources of discomfort from conditions such as arthritic pain.38,39 If nonpharmacologic therapies are not effective, pharmacologic options can be considered.4 Before prescribing sleep medications, it may be more fruitful to treat underlying psychiatric disorders such as depression and anxiety with antidepressants.4 Although benzodiazepines are helpful for their sedative effects, they are not recommended for older adults because of an increased risk of falls, rebound insomnia, potential tolerance, and associated cognitive impairment.40 Benzodiazepine receptor agonists (eg, zolpidem, eszopiclone, zaleplon) were initially developed as a first-line treatment for insomnia to replace the reliance on benzodiazepines, but these medications have a “black-box” warning of a serious risk of complex sleep behaviors, including life-threatening parasomnias.41 As a result, guidelines suggest a shorter duration of treatment with a benzodiazepine receptor agonist may still provide benefit while limiting the risk of adverse effects.42

Doxepin is the only antidepressant FDA-approved for insomnia; it improves sleep latency (time taken to initiate sleep after lying down), duration, and quality in adults age >65.43 Melatonin receptor agonists such as ramelteon and melatonin have shown positive results in older patients with insomnia. In clinical trials of patients age ≥65, ramelteon, which is FDA-approved for insomnia, produced no rebound insomnia, withdrawal effects, memory impairment, or gait instability.44-46 Suvorexant, an orexin receptor antagonist, decreases sleep latency and increases total sleep time equally in both young and older adults.47-49Table 340-51 provides a list of medications used to treat insomnia (including off-label agents) and their common adverse effects in older adults.

Parasomnias are undesirable behaviors that occur during sleep, commonly associated with the sleep-wake transition period. These behaviors can occur during REM sleep (nightmare disorder, sleep paralysis, REM sleep behavior disorder) or NREM sleep (somnambulism [sleepwalking], confusional arousals, sleep terrors). According to a cross-sectional Norwegian study of parasomnias, the estimated lifetime prevalence of sleep walking is 22.4%; sleep talking, 66.8%; confusional arousal, 18.5%; and sleep terror, 10.4%.52

Continue to: When evaluating a patient...

When evaluating a patient with parasomnias, it is important to review their drug and substance use as well as coexisting medical conditions. Drugs and substances that can affect sleep include prescription medications (second-generation antidepressants, stimulants, dopamine agonists), excessive caffeine, alcohol, certain foods (coffee, chocolate milk, black tea, caffeinated soft drinks), environmental exposures (smoking, pesticides), and recreational drugs (amphetamines).53-56 Certain medical conditions are correlated with specific parasomnias (eg, sleep paralysis and narcolepsy, REM sleep behavior disorder and Parkinson’s disease [PD], etc.).54 Diagnosis of parasomnias is mainly clinical but supporting evidence can be obtained through in-lab polysomnography.

Treatment. For parasomnias, treatment is primarily supportive and includes creating a safe sleeping environment to reduce the risk of self-harm. Recommendations include sleeping in a room on the ground floor, minimizing furniture in the bedroom, padding any bedside furniture, child-proofing doorknobs, and locking up weapons and other dangerous household items.54

REM sleep behavior disorder (RBD). This disorder is characterized by a loss of the typical REM sleep-associated atonia and the presence of motor activity during dreaming (dream-enacted behaviors). While the estimated incidence of RBD in the general adult population is approximately 0.5%, it increases to 7.7% among those age >60.57 RBD occurs most commonly in the setting of the alpha-synucleinopathies (PD, Lewy body dementia, multisystem atrophy), but can also be found in patients with cerebral ischemia, demyelinating disorders, or alcohol misuse, or can be medication-induced (primarily antidepressants and antipsychotics).58 In patients with PD, the presence of RBD is associated with a more impaired cognitive profile, suggestive of widespread neurodegeneration.59 Recent studies revealed that RBD may also be a prodromal state of neurodegenerative diseases such as PD, which should prompt close monitoring and long-term follow up.60 Similar to other parasomnias, the diagnosis of RBD is primarily clinical, but polysomnography plays an important role in demonstrating loss of REM-related atonia.54

Treatment. Clonazepam and melatonin have been shown to be effective in treating the symptoms of RBD.54

Depression, anxiety, and sleep disturbances

Major depressive disorder (MDD) and generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) affect sleep in patients of all ages, but are underreported in older adults. According to national epidemiologic surveys, the estimated prevalence of MDD and GAD among older adults is 13% and 11.4%, respectively.61,62 Rates as high as 42% and 39% have been reported in meta-regression analyses among patients with Alzheimer’s dementia.63

Continue to: Depression and anxiety

Depression and anxiety may have additive effects and manifest as poor sleep satisfaction, increased sleep latency, insomnia, and daytime sleepiness.64 However, they may also have independent effects. Studies showed that patients with depression alone reported overall poor sleep satisfaction, whereas patients with anxiety alone reported problems with sleep latency, daytime drowsiness, and waking up at night in addition to their overall poor sleep satisfaction.65-67 Both depression and anxiety are risk factors for developing cognitive decline, and may be an early sign/prodrome of neurodegenerative diseases (dementias).68 The bidirectional relationship between depression/anxiety and sleep is complex and needs further investigation.

Treatment. Pharmacologic treatments for patients with depression/anxiety and sleep disturbances include selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, tricyclic antidepressants, and other serotonin receptor agonists.69-72 Nonpharmacologic treatments include CBT for both depression and anxiety, and problem-solving therapy for patients with mild cognitive impairment and depression.73,74 For severe depression and/or anxiety, electroconvulsive therapy is effective.75

Bottom Line

Sleep disorders in older adults are common but often underdiagnosed. Timely recognition of obstructive sleep apnea, central sleep apnea, insomnia, parasomnias, and other sleep disturbances can facilitate effective treatment and greatly improve older adults’ quality of life.

Related Resources

- American Academy of Sleep Medicine. International Classification of Sleep Disorders—Third Edition. https://aasm.org

- SleepFoundation.org. Sleep hygiene. https://www.sleepfoundation.org/articles/sleep-hygiene

Drug Brand Names

Acetazolamide • Diamox

Clonazepam • Klonopin

Doxepin • Silenor

Eszopiclone • Lunesta

Gabapentin • Neurontin

Mirtazapine • Remeron

Pramipexole • Mirapex

Quetiapine • Seroquel

Ramelteon • Rozerem

Suvorexant • Belsomra

Temazepam • Restoril

Theophylline • Elixophyllin

Tiagabine • Gabitril

Trazadone • Desyrel

Triazolam • Halcion

Zaleplon • Sonata

Zolpidem • Ambien

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The state of aging and health in America. 2013. Accessed January 27, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/aging/pdf/state-aging-health-in-america-2013.pdf

2. Suzuki K, Miyamoto M, Hirata K. Sleep disorders in the elderly: diagnosis and management. J Gen Fam Med. 2017;18(2):61-71.

3. Inouye SK, Studenski S, Tinetti ME, et al. Geriatric syndromes: clinical, research, and policy implications of a core geriatric concept. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55(5):780-791.

4. Patel D, Steinberg J, Patel P. Insomnia in the elderly: a review. J Clin Sleep Med. 2018;14(6):1017-1024.

5. Neubauer DN. A review of ramelteon in the treatment of sleep disorders. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2008;4(1):69-79.

6. Mander BA, Winer JR, Walker MP. Sleep and human aging. Neuron. 2017;94(1):19-36.

7. Ohayon MM, Carskadon MA, Guilleminault C, et al. Meta-analysis of quantitative sleep parameters from childhood to old age in healthy individuals: developing normative sleep values across the human lifespan. Sleep. 2004;27:1255-1273.

8. Li J, Vitiello MV, Gooneratne NS. Sleep in normal aging. Sleep Med Clin. 2018;13(1):1-11.

9. Floyd JA, Medler SM, Ager JW, et al. Age-related changes in initiation and maintenance of sleep: a meta-analysis. Res Nurs Health. 2000;23(2):106-117.

10. Floyd JA, Janisse JJ, Jenuwine ES, et al. Changes in REM-sleep percentage over the adult lifespan. Sleep. 2007;30(7):829-836.

11. Dorffner G, Vitr M, Anderer P. The effects of aging on sleep architecture in healthy subjects. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2015;821:93-100.

12. Furihata R, Kaneita Y, Jike M, et al. Napping and associated factors: a Japanese nationwide general population survey. Sleep Med. 2016;20:72-79.

13. Foley DJ, Vitiello MV, Bliwise DL, et al. Frequent napping is associated with excessive daytime sleepiness, depression, pain, and nocturia in older adults: findings from the National Sleep Foundation ‘2003 Sleep in America’ Poll. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007;15(4):344-350.

14. Floyd JA, Janisse JJ, Marshall Medler S, et al. Nonlinear components of age-related change in sleep initiation. Nurs Res. 2000;49(5):290-294.

15. Miner B, Kryger MH. Sleep in the aging population. Sleep Med Clin. 2017;12(1):31-38.

16. Young T, Peppard PE, Gottlieb DJ. Epidemiology of obstructive sleep apnea: a population health perspective. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;165(9):1217-1239.

17. Ancoli-Israel S, Klauber MR, Butters N, et al. Dementia in institutionalized elderly: relation to sleep apnea. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1991;39(3):258-263.

18. Spira AP, Stone KL, Rebok GW, et al. Sleep-disordered breathing and functional decline in older women. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62(11):2040-2046.

19. Vijayan VK. Morbidities associated with obstructive sleep apnea. Expert Rev Respir Med. 2012;6(5):557-566.

20. Kerner NA, Roose SP. Obstructive sleep apnea is linked to depression and cognitive impairment: evidence and potential mechanisms. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2016;24(6):496-508.

21. Dalmases M, Solé-Padullés C, Torres M, et al. Effect of CPAP on cognition, brain function, and structure among elderly patients with OSA: a randomized pilot study. Chest. 2015;148(5):1214-1223.

22. Toronto Western Hospital, University Health Network. University of Toronto. STOP-Bang Questionnaire. 2012. Accessed January 26, 2021. www.stopbang.ca

23. Freedman N. Doing it better for less: incorporating OSA management into alternative payment models. Chest. 2019;155(1):227-233.

24. Kapur VK, Auckley DH, Chowdhuri S, et al. Clinical practice guideline for diagnostic testing for adult obstructive sleep apnea: an American Academy of Sleep Medicine clinical practice guideline. J Clin Sleep Med. 2017;13(3):479-504.

25. Semelka M, Wilson J, Floyd R. Diagnosis and treatment of obstructive sleep apnea in adults. Am Fam Physician. 2016;94(5):355-360.

26. Javaheri S, Dempsey JA. Central sleep apnea. Compr Physiol. 2013;3(1):141-163.

27. Donovan LM, Kapur VK. Prevalence and characteristics of central compared to obstructive sleep apnea: analyses from the Sleep Heart Health Study cohort. Sleep. 2016;39(7):1353-1359.

28. Cao M, Cardell CY, Willes L, et al. A novel adaptive servoventilation (ASVAuto) for the treatment of central sleep apnea associated with chronic use of opioids. J Clin Sleep Med. 2014;10(8):855-861.

29. Oldenburg O, Spießhöfer J, Fox H, et al. Performance of conventional and enhanced adaptive servoventilation (ASV) in heart failure patients with central sleep apnea who have adapted to conventional ASV. Sleep Breath. 2015;19(3):795-800.

30. Costanzo MR, Ponikowski P, Javaheri S, et al. Transvenous neurostimulation for central sleep apnoea: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2016;388(10048):974-982.

31. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association; 2013:362.

32. Perlis ML, Smith LJ, Lyness JM, et al. Insomnia as a risk factor for onset of depression in the elderly. Behav Sleep Med. 2006;4(2):104-113.

33. Cole MG, Dendukuri N. Risk factors for depression among elderly community subjects: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(6):1147-1156.

34. Pigeon WR, Hegel M, Unützer J, et al. Is insomnia a perpetuating factor for late-life depression in the IMPACT cohort? Sleep. 2008;31(4):481-488.

35. Hughes JM, Song Y, Fung CH, et al. Measuring sleep in vulnerable older adults: a comparison of subjective and objective sleep measures. Clin Gerontol. 2018;41(2):145-157.

36. Irish LA, Kline CE, Gunn HE, et al. The role of sleep hygiene in promoting public health: a review of empirical evidence. Sleep Med Rev. 2015;22:23-36.

37. Sleep Foundation. Sleep hygiene. Accessed January 27, 2021. https://www.sleepfoundation.org/articles/sleep-hygiene

38. Foley D, Ancoli-Israel S, Britz P, et al. Sleep disturbances and chronic disease in older adults: results of the 2003 National Sleep Foundation Sleep in America Survey. J Psychosom Res. 2004;56(5):497-502.

39. Eslami V, Zimmerman ME, Grewal T, et al. Pain grade and sleep disturbance in older adults: evaluation the role of pain, and stress for depressed and non-depressed individuals. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2016;31(5):450-457.

40. American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society 2015 updated Beers Criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63(11):2227-2246.

41. United States Food & Drug Administration. FDA adds Boxed Warning for risk of serious injuries caused by sleepwalking with certain prescription insomnia medicines. 2019. Accessed January 27, 2021. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/fda-adds-boxed-warning-risk-serious-injuries-caused-sleepwalking-certain-prescription-insomnia

42. Schroeck JL, Ford J, Conway EL, et al. Review of safety and efficacy of sleep medicines in older adults. Clin Ther. 2016;38(11):2340-2372.

43. Krystal AD, Lankford A, Durrence HH, et al. Efficacy and safety of doxepin 3 and 6 mg in a 35-day sleep laboratory trial in adults with chronic primary insomnia. Sleep. 2011;34(10):1433-1442.

44. Roth T, Seiden D, Sainati S, et al. Effects of ramelteon on patient-reported sleep latency in older adults with chronic insomnia. Sleep Med. 2006;7(4):312-318.

45. Zammit G, Wang-Weigand S, Rosenthal M, et al. Effect of ramelteon on middle-of-the-night balance in older adults with chronic insomnia. J Clin Sleep Med. 2009;5(1):34-40.

46. Mets MAJ, de Vries JM, de Senerpont Domis LM, et al. Next-day effects of ramelteon (8 mg), zopiclone (7.5 mg), and placebo on highway driving performance, memory functioning, psychomotor performance, and mood in healthy adult subjects. Sleep. 2011;34(10):1327-1334.

47. Rhyne DN, Anderson SL. Suvorexant in insomnia: efficacy, safety and place in therapy. Ther Adv Drug Saf. 2015;6(5):189-195.

48. Norman JL, Anderson SL. Novel class of medications, orexin receptor antagonists, in the treatment of insomnia - critical appraisal of suvorexant. Nat Sci Sleep. 2016;8:239-247.

49. Owen RT. Suvorexant: efficacy and safety profile of a dual orexin receptor antagonist in treating insomnia. Drugs Today (Barc). 2016;52(1):29-40.

50. Shannon S, Lewis N, Lee H, et al. Cannabidiol in anxiety and sleep: a large case series. Perm J. 2019;23:18-041. doi: 10.7812/TPP/18-041

51. Yunusa I, Alsumali A, Garba AE, et al. Assessment of reported comparative effectiveness and safety of atypical antipsychotics in the treatment of behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia: a network meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(3):e190828.

52. Bjorvatn B, Gronli J, Pallesen S. Prevalence of different parasomnias in the general population. Sleep Med. 2010;11(10):1031-1034.

53. Postuma RB, Montplaisir JY, Pelletier A, et al. Environmental risk factors for REM sleep behavior disorder: a multicenter case-control study. Neurology. 2012;79(5):428-434.

54. Fleetham JA, Fleming JA. Parasomnias. CMAJ. 2014;186(8):E273-E280.

55. Dinis-Oliveira RJ, Caldas I, Carvalho F, et al. Bruxism after 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (ecstasy) abuse. Clin Toxicol (Phila.) 2010;48(8):863-864.

56. Irfan MH, Howell MJ. Rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder: overview and current perspective. Curr Sleep Medicine Rep. 2016;2:64-73.

57. Mahlknecht P, Seppi K, Frauscher B, et al. Probable RBD and association with neurodegenerative disease markers: a population-based study. Mov Disord. 2015;30(10):1417-1421.

58. Oertel WH, Depboylu C, Krenzer M, et al. [REM sleep behavior disorder as a prodromal stage of α-synucleinopathies: symptoms, epidemiology, pathophysiology, diagnosis and therapy]. Nervenarzt. 2014;85:19-25. German.

59. Jozwiak N, Postuma RB, Montplaisir J, et al. REM sleep behavior disorder and cognitive impairment in Parkinson’s disease. Sleep. 2017;40(8):zsx101. doi: 10.1093/sleep/zsx101

60. Claassen DO, Josephs KA, Ahlskog JE, et al. REM sleep behavior disorder preceding other aspects of synucleinopathies by up to half a century. Neurology 2010;75(6):494-499.

61. Reynolds K, Pietrzak RH, El-Gabalawy R, et al. Prevalence of psychiatric disorders in U.S. older adults: findings from a nationally representative survey. World Psychiatry. 2015;14(1):74-81.

62. Lohman MC, Mezuk B, Dumenci L. Depression and frailty: concurrent risks for adverse health outcomes. Aging Ment Health. 2017;21(4):399-408.

63. Zhao QF, Tan L, Wang HF, et al. The prevalence of neuropsychiatric symptoms in Alzheimer’s disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2016;190:264-271.

64. Furihata R, Hall MH, Stone KL, et al. An aggregate measure of sleep health is associated with prevalent and incident clinically significant depression symptoms among community-dwelling older women. Sleep. 2017;40(3):zsw075. doi: 10.1093/sleep/zsw075

65. Spira AP, Stone K, Beaudreau SA, et al. Anxiety symptoms and objectively measured sleep quality in older women. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009;17(2):136-143.

66. Press Y, Punchik B, Freud T. The association between subjectively impaired sleep and symptoms of depression and anxiety in a frail elderly population. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2018;30(7):755-765.

67. Gould CE, Spira AP, Liou-Johnson V, et al. Association of anxiety symptom clusters with sleep quality and daytime sleepiness. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2018;73(3):413-420.

68. Kassem AM, Ganguli M, Yaffe K, et al. Anxiety symptoms and risk of cognitive decline in older community-dwelling men. Int Psychogeriatr. 2017;29(7):1137-1145.

69. Frank C. Pharmacologic treatment of depression in the elderly. Can Fam Physician. 2014;60(2):121-126.

70. Subramanyam AA, Kedare J, Singh OP, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for geriatric anxiety disorders. Indian J Psychiatry. 2018;60(suppl 3):S371-S382.

71. Emsley R, Ahokas A, Suarez A, et al. Efficacy of tianeptine 25-50 mg in elderly patients with recurrent major depressive disorder: an 8-week placebo- and escitalopram-controlled study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2018;79(4):17m11741. doi: 10.4088/JCP.17m11741

72. Semel D, Murphy TK, Zlateva G, et al. Evaluation of the safety and efficacy of pregabalin in older patients with neuropathic pain: results from a pooled analysis of 11 clinical studies. BMC Fam Pract. 2010;11:85.

73. Orgeta V, Qazi A, Spector A, et al. Psychological treatments for depression and anxiety in dementia and mild cognitive impairment: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2015;207(4):293-298.

74. Morimoto SS, Kanellopoulos D, Manning KJ, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of depression and cognitive impairment in late life. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2015;1345(1):36-46.

75. Casey DA. Depression in older adults: a treatable medical condition. Prim Care. 2017;44(3):499-510.

As humans live longer, a renewed focus on quality of life has made the prompt diagnosis and treatment of sleep-related disorders in older adults increasingly necessary.1 Normative aging results in multiple changes in sleep architecture, including decreased total sleep time, decreased sleep efficiency, decreased slow-wave sleep (SWS), and increased awakenings after sleep onset.2 Sleep disturbances in older adults are increasingly recognized as multifactorial health conditions requiring comprehensive modification of risk factors, diagnosis, and treatment.3

In this article, we discuss the effects of aging on sleep architecture and provide an overview of primary sleep disorders in older adults. We also summarize strategies for diagnosing and treating sleep disorders in these patients.

Elements of the sleep cycle

The human sleep cycle begins with light sleep (sleep stages 1 and 2), progresses into SWS (sleep stage 3), and culminates in rapid eye movement (REM) sleep. The first 3 stages are referred to as non-rapid eye movement sleep (NREM). Throughout the night, this coupling of NREM and REM cycles occurs 4 to 6 times, with each successive cycle decreasing in length until awakening.4

Two complex neurologic pathways intersect to regulate the timing of sleep and wakefulness on arousal. The first pathway, the circadian system, is located within the suprachiasmatic nucleus of the hypothalamus and is highly dependent on external stimuli (light, food, etc.) to synchronize sleep/wake cycles. The suprachiasmatic nucleus regulates melatonin secretion by the pineal gland, which signals day-night transitions. The other pathway, the homeostatic system, modifies the amount of sleep needed daily. When multiple days of poor sleep occur, homeostatic sleep pressure (colloquially described as sleep debt) compensates by increasing the amount of sleep required in the following days. Together, the circadian and homeostatic systems work in conjunction to regulate sleep quantity to approximately one-third of the total sleep-wake cycle.2,5

Age-related dysfunction of the regulatory sleep pathways leads to blunting of the ability to initiate and sustain high-quality sleep.6 Dysregulation of homeostatic sleep pressure decreases time spent in SWS, and failure of the circadian signaling apparatus results in delays in sleep/wake timing.2 While research into the underlying neurobiology of sleep reveals that some of these changes are inherent to aging (Box7-14), significant underdiagnosed pathologies may adversely affect sleep architecture, including polypharmacy, comorbid neuropathology (eg, synucleinopathies, tauopathies, etc.), and primary sleep disorders (insomnias, hypersomnias, and parasomnias).15

Box

It has long been known that sleep architecture changes significantly with age. One of the largest meta-analyses of sleep changes in healthy individuals throughout childhood into old age found that total sleep time, sleep efficiency, percentage of slow-wave sleep, percentage of rapid eye movement sleep (REM), and REM latency all decreased with normative aging.7 Other studies have also found a decreased ability to maintain sleep (increased frequency of awakenings and prolonged nocturnal awakenings).8

Based on several meta-analyses, the average total sleep time at night in the adult population decreases by approximately 10 minutes per decade in both men and women.7,9-11 However, this pattern is not observed after age 60, when the total sleep time plateaus.7 Similarly, the duration of wake after sleep onset increases by approximately 10 minutes every decade for adults age 30 to 60, and plateaus after that.7,8

Epidemiologic studies have suggested that the prevalence of daytime napping increases with age.8 This trend continues into older age without a noticeable plateau.

A study of a nationally representative sample of >7,000 Japanese participants found that a significantly higher proportion of older adults take daytime naps (27.4%) compared with middle-age adults (14.4%).12 Older adults nap more frequently because of both lifestyle and biologic changes that accompany normative aging. Polls in the United States have shown a correlation between frequent napping and an increase in excessive daytime sleepiness, depression, pain, and nocturia.13

While sleep latency steadily increases after age 50, recent studies have shown that in healthy individuals, these changes are modest at best,7,9,14 which suggests that other pathologic factors may be contributing to this problem. Although healthy older people were found to have more frequent arousals throughout the night, they retained the ability to reinitiate sleep as rapidly as younger adults.7,9

Primary sleep disorders

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is one of the most common, yet frequently underdiagnosed reversible causes of sleep disturbances. It is characterized by partial or complete airway obstruction culminating in periods of involuntary cessation of respirations during sleep. The resultant fragmentation in sleep leads to significant downstream effects over time, including excessive daytime sleepiness and fatigue, poor occupational and social performance, and substantial cognitive impairment.3 While it is well known that OSA increases in prevalence throughout middle age, this relationship plateaus after age 60.16 An estimated 40% to 60% of Americans age >60 are affected by OSA.17 The hypoxemia and fragmented sleep caused by unrecognized OSA are associated with a significant decline in activities of daily living (ADL).18 Untreated OSA is strongly linked to the development and progression of several major health conditions, including cardiovascular disease, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, stroke, and depression.19 In studies of long-term care facility residents—many of whom may have comorbid cognitive decline—researchers found that unrecognized OSA often mimics the progressive cognitive decline seen in major neurocognitive disorders.20 However, classic symptoms of OSA may not always be present in these patients, and their daytime sleepiness is often attributed to old age rather than to a pathological etiology.16 Screening for OSA and prompt initiation of the appropriate treatment may reverse OSA-induced cognitive changes in these patients.21

The primary presenting symptom of OSA is snoring, which is correlated with pauses in breathing. Risk factors include increased body mass index (BMI), thick neck circumference, male sex, and advanced age. In older adults, BMI has a lower impact on the Apnea-Hypopnea Index, an indicator of the number of pauses in breathing per hour, when compared with young and middle-age adults.16 Validated screening questionnaires for OSA include the STOP-Bang Questionnaire (Table 122), OSA50, Berlin Questionnaire, and Epworth Sleepiness Scale, each of which is used in different subpopulations. The current diagnostic standard for OSA is nocturnal polysomnography in a sleep laboratory, but recent advances in home sleep apnea testing have made it a viable, low-cost alternative for patients who do not have significant medical comorbidities.23 Standard utilized cutoffs for diagnosis are ≥5 events/hour (hypopneas associated with at least 4% oxygen desaturations) in conjunction with clinical symptoms of OSA.24

Continue to: Treatment

Treatment. First-line treatment for OSA is continuous positive airway pressure therapy, but adherence rates vary widely with patient education and regular follow-up.25 Adjunctive therapy includes weight loss, oral appliances, and uvulopalatopharyngoplasty, a procedure in which tissue in the throat is remodeled or removed.

Central sleep apnea (CSA) is a pause in breathing without evidence of associated respiratory effort. In adults, the development of CSA is indicative of underlying lower brainstem dysfunction, due to intermittent failures in the pontomedullary centers responsible for regulation of rhythmic breathing.26 This can occur as a consequence of multiple diseases, including congestive heart failure, stroke, renal failure, chronic medication use (opioids), and brain tumors.

The Sleep Heart Health Study—the largest community-based cohort study to date examining CSA—estimated that the prevalence of CSA among adults age >65 was 1.1% (compared with 0.4% in those age <65).27 Subgroup analysis revealed that men had significantly higher rates of CSA compared with women (2.7% vs 0.2%, respectively).

CSA may present similarly to OSA (excessive daytime somnolence, insomnia, poor sleep quality, difficulties with attention and concentration). Symptoms may also mimic those of coexisting medical conditions in older adults, such as nocturnal angina or paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea.27 Any older patient with daytime sleepiness and risk factors for CSA should be referred for in-laboratory nocturnal polysomnography, the gold standard diagnostic test. Unlike in OSA, ambulatory diagnostic measures (home sleep apnea testing) have not been validated for this disorder.27

Treatment. The primary treatment for CSA is to address the underlying medical problem. Positive pressure ventilation has been attempted with mixed results. Supplemental oxygen and medical management (acetazolamide or theophylline) can help stimulate breathing. Newer studies have shown favorable outcomes with transvenous neurostimulation or adaptive servoventilation.28-30

Continue to: Insomnia

Insomnia. For a primary diagnosis of insomnia, DSM-5 requires at least 3 nights per week of sleep disturbances that induce distress or functional impairment for at least 3 months.31 The International Classification of Disease, 10th Edition requires at least 1 month of symptoms (lying awake for a long time before falling asleep, sleeping for short periods, being awake for most of the night, feeling lack of sleep, waking up early) after ruling out other sleep disorders, substance use, or other medical conditions.4 Clinically, insomnia tends to present in older adults as a subjective complaint of dissatisfaction with the quality and/or quantity of their sleep. Insomnia has been consistently shown to be a significant risk factor for both the development or exacerbation of depression in older adults.32-34

While the diagnosis of insomnia is mainly clinical via a thorough sleep and medication history, assistive ancillary testing can include wrist actigraphy and screening questionnaires (the Insomnia Severity Index and the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index).4 Because population studies of older adults have found discrepancies between objective and subjective methods of assessing sleep quality, relying on the accuracy of self-reported symptoms alone is questionable.35

Treatment. Given that drug elimination half-life increases with age, and the risks of adverse effects are increased in older adults, the preferred treatment modalities for insomnia are nonpharmacologic.4 Sleep hygiene education (Table 2) and cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) for insomnia are often the first-line therapies.4,36,37 It is crucial to manage comorbidities such as heart disease and obesity, as well as sources of discomfort from conditions such as arthritic pain.38,39 If nonpharmacologic therapies are not effective, pharmacologic options can be considered.4 Before prescribing sleep medications, it may be more fruitful to treat underlying psychiatric disorders such as depression and anxiety with antidepressants.4 Although benzodiazepines are helpful for their sedative effects, they are not recommended for older adults because of an increased risk of falls, rebound insomnia, potential tolerance, and associated cognitive impairment.40 Benzodiazepine receptor agonists (eg, zolpidem, eszopiclone, zaleplon) were initially developed as a first-line treatment for insomnia to replace the reliance on benzodiazepines, but these medications have a “black-box” warning of a serious risk of complex sleep behaviors, including life-threatening parasomnias.41 As a result, guidelines suggest a shorter duration of treatment with a benzodiazepine receptor agonist may still provide benefit while limiting the risk of adverse effects.42

Doxepin is the only antidepressant FDA-approved for insomnia; it improves sleep latency (time taken to initiate sleep after lying down), duration, and quality in adults age >65.43 Melatonin receptor agonists such as ramelteon and melatonin have shown positive results in older patients with insomnia. In clinical trials of patients age ≥65, ramelteon, which is FDA-approved for insomnia, produced no rebound insomnia, withdrawal effects, memory impairment, or gait instability.44-46 Suvorexant, an orexin receptor antagonist, decreases sleep latency and increases total sleep time equally in both young and older adults.47-49Table 340-51 provides a list of medications used to treat insomnia (including off-label agents) and their common adverse effects in older adults.

Parasomnias are undesirable behaviors that occur during sleep, commonly associated with the sleep-wake transition period. These behaviors can occur during REM sleep (nightmare disorder, sleep paralysis, REM sleep behavior disorder) or NREM sleep (somnambulism [sleepwalking], confusional arousals, sleep terrors). According to a cross-sectional Norwegian study of parasomnias, the estimated lifetime prevalence of sleep walking is 22.4%; sleep talking, 66.8%; confusional arousal, 18.5%; and sleep terror, 10.4%.52

Continue to: When evaluating a patient...

When evaluating a patient with parasomnias, it is important to review their drug and substance use as well as coexisting medical conditions. Drugs and substances that can affect sleep include prescription medications (second-generation antidepressants, stimulants, dopamine agonists), excessive caffeine, alcohol, certain foods (coffee, chocolate milk, black tea, caffeinated soft drinks), environmental exposures (smoking, pesticides), and recreational drugs (amphetamines).53-56 Certain medical conditions are correlated with specific parasomnias (eg, sleep paralysis and narcolepsy, REM sleep behavior disorder and Parkinson’s disease [PD], etc.).54 Diagnosis of parasomnias is mainly clinical but supporting evidence can be obtained through in-lab polysomnography.

Treatment. For parasomnias, treatment is primarily supportive and includes creating a safe sleeping environment to reduce the risk of self-harm. Recommendations include sleeping in a room on the ground floor, minimizing furniture in the bedroom, padding any bedside furniture, child-proofing doorknobs, and locking up weapons and other dangerous household items.54

REM sleep behavior disorder (RBD). This disorder is characterized by a loss of the typical REM sleep-associated atonia and the presence of motor activity during dreaming (dream-enacted behaviors). While the estimated incidence of RBD in the general adult population is approximately 0.5%, it increases to 7.7% among those age >60.57 RBD occurs most commonly in the setting of the alpha-synucleinopathies (PD, Lewy body dementia, multisystem atrophy), but can also be found in patients with cerebral ischemia, demyelinating disorders, or alcohol misuse, or can be medication-induced (primarily antidepressants and antipsychotics).58 In patients with PD, the presence of RBD is associated with a more impaired cognitive profile, suggestive of widespread neurodegeneration.59 Recent studies revealed that RBD may also be a prodromal state of neurodegenerative diseases such as PD, which should prompt close monitoring and long-term follow up.60 Similar to other parasomnias, the diagnosis of RBD is primarily clinical, but polysomnography plays an important role in demonstrating loss of REM-related atonia.54

Treatment. Clonazepam and melatonin have been shown to be effective in treating the symptoms of RBD.54

Depression, anxiety, and sleep disturbances

Major depressive disorder (MDD) and generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) affect sleep in patients of all ages, but are underreported in older adults. According to national epidemiologic surveys, the estimated prevalence of MDD and GAD among older adults is 13% and 11.4%, respectively.61,62 Rates as high as 42% and 39% have been reported in meta-regression analyses among patients with Alzheimer’s dementia.63

Continue to: Depression and anxiety

Depression and anxiety may have additive effects and manifest as poor sleep satisfaction, increased sleep latency, insomnia, and daytime sleepiness.64 However, they may also have independent effects. Studies showed that patients with depression alone reported overall poor sleep satisfaction, whereas patients with anxiety alone reported problems with sleep latency, daytime drowsiness, and waking up at night in addition to their overall poor sleep satisfaction.65-67 Both depression and anxiety are risk factors for developing cognitive decline, and may be an early sign/prodrome of neurodegenerative diseases (dementias).68 The bidirectional relationship between depression/anxiety and sleep is complex and needs further investigation.

Treatment. Pharmacologic treatments for patients with depression/anxiety and sleep disturbances include selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, tricyclic antidepressants, and other serotonin receptor agonists.69-72 Nonpharmacologic treatments include CBT for both depression and anxiety, and problem-solving therapy for patients with mild cognitive impairment and depression.73,74 For severe depression and/or anxiety, electroconvulsive therapy is effective.75

Bottom Line

Sleep disorders in older adults are common but often underdiagnosed. Timely recognition of obstructive sleep apnea, central sleep apnea, insomnia, parasomnias, and other sleep disturbances can facilitate effective treatment and greatly improve older adults’ quality of life.

Related Resources

- American Academy of Sleep Medicine. International Classification of Sleep Disorders—Third Edition. https://aasm.org

- SleepFoundation.org. Sleep hygiene. https://www.sleepfoundation.org/articles/sleep-hygiene

Drug Brand Names

Acetazolamide • Diamox

Clonazepam • Klonopin

Doxepin • Silenor

Eszopiclone • Lunesta

Gabapentin • Neurontin

Mirtazapine • Remeron

Pramipexole • Mirapex

Quetiapine • Seroquel

Ramelteon • Rozerem

Suvorexant • Belsomra

Temazepam • Restoril

Theophylline • Elixophyllin

Tiagabine • Gabitril

Trazadone • Desyrel

Triazolam • Halcion

Zaleplon • Sonata

Zolpidem • Ambien

As humans live longer, a renewed focus on quality of life has made the prompt diagnosis and treatment of sleep-related disorders in older adults increasingly necessary.1 Normative aging results in multiple changes in sleep architecture, including decreased total sleep time, decreased sleep efficiency, decreased slow-wave sleep (SWS), and increased awakenings after sleep onset.2 Sleep disturbances in older adults are increasingly recognized as multifactorial health conditions requiring comprehensive modification of risk factors, diagnosis, and treatment.3

In this article, we discuss the effects of aging on sleep architecture and provide an overview of primary sleep disorders in older adults. We also summarize strategies for diagnosing and treating sleep disorders in these patients.

Elements of the sleep cycle

The human sleep cycle begins with light sleep (sleep stages 1 and 2), progresses into SWS (sleep stage 3), and culminates in rapid eye movement (REM) sleep. The first 3 stages are referred to as non-rapid eye movement sleep (NREM). Throughout the night, this coupling of NREM and REM cycles occurs 4 to 6 times, with each successive cycle decreasing in length until awakening.4

Two complex neurologic pathways intersect to regulate the timing of sleep and wakefulness on arousal. The first pathway, the circadian system, is located within the suprachiasmatic nucleus of the hypothalamus and is highly dependent on external stimuli (light, food, etc.) to synchronize sleep/wake cycles. The suprachiasmatic nucleus regulates melatonin secretion by the pineal gland, which signals day-night transitions. The other pathway, the homeostatic system, modifies the amount of sleep needed daily. When multiple days of poor sleep occur, homeostatic sleep pressure (colloquially described as sleep debt) compensates by increasing the amount of sleep required in the following days. Together, the circadian and homeostatic systems work in conjunction to regulate sleep quantity to approximately one-third of the total sleep-wake cycle.2,5

Age-related dysfunction of the regulatory sleep pathways leads to blunting of the ability to initiate and sustain high-quality sleep.6 Dysregulation of homeostatic sleep pressure decreases time spent in SWS, and failure of the circadian signaling apparatus results in delays in sleep/wake timing.2 While research into the underlying neurobiology of sleep reveals that some of these changes are inherent to aging (Box7-14), significant underdiagnosed pathologies may adversely affect sleep architecture, including polypharmacy, comorbid neuropathology (eg, synucleinopathies, tauopathies, etc.), and primary sleep disorders (insomnias, hypersomnias, and parasomnias).15

Box

It has long been known that sleep architecture changes significantly with age. One of the largest meta-analyses of sleep changes in healthy individuals throughout childhood into old age found that total sleep time, sleep efficiency, percentage of slow-wave sleep, percentage of rapid eye movement sleep (REM), and REM latency all decreased with normative aging.7 Other studies have also found a decreased ability to maintain sleep (increased frequency of awakenings and prolonged nocturnal awakenings).8

Based on several meta-analyses, the average total sleep time at night in the adult population decreases by approximately 10 minutes per decade in both men and women.7,9-11 However, this pattern is not observed after age 60, when the total sleep time plateaus.7 Similarly, the duration of wake after sleep onset increases by approximately 10 minutes every decade for adults age 30 to 60, and plateaus after that.7,8

Epidemiologic studies have suggested that the prevalence of daytime napping increases with age.8 This trend continues into older age without a noticeable plateau.

A study of a nationally representative sample of >7,000 Japanese participants found that a significantly higher proportion of older adults take daytime naps (27.4%) compared with middle-age adults (14.4%).12 Older adults nap more frequently because of both lifestyle and biologic changes that accompany normative aging. Polls in the United States have shown a correlation between frequent napping and an increase in excessive daytime sleepiness, depression, pain, and nocturia.13

While sleep latency steadily increases after age 50, recent studies have shown that in healthy individuals, these changes are modest at best,7,9,14 which suggests that other pathologic factors may be contributing to this problem. Although healthy older people were found to have more frequent arousals throughout the night, they retained the ability to reinitiate sleep as rapidly as younger adults.7,9

Primary sleep disorders

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is one of the most common, yet frequently underdiagnosed reversible causes of sleep disturbances. It is characterized by partial or complete airway obstruction culminating in periods of involuntary cessation of respirations during sleep. The resultant fragmentation in sleep leads to significant downstream effects over time, including excessive daytime sleepiness and fatigue, poor occupational and social performance, and substantial cognitive impairment.3 While it is well known that OSA increases in prevalence throughout middle age, this relationship plateaus after age 60.16 An estimated 40% to 60% of Americans age >60 are affected by OSA.17 The hypoxemia and fragmented sleep caused by unrecognized OSA are associated with a significant decline in activities of daily living (ADL).18 Untreated OSA is strongly linked to the development and progression of several major health conditions, including cardiovascular disease, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, stroke, and depression.19 In studies of long-term care facility residents—many of whom may have comorbid cognitive decline—researchers found that unrecognized OSA often mimics the progressive cognitive decline seen in major neurocognitive disorders.20 However, classic symptoms of OSA may not always be present in these patients, and their daytime sleepiness is often attributed to old age rather than to a pathological etiology.16 Screening for OSA and prompt initiation of the appropriate treatment may reverse OSA-induced cognitive changes in these patients.21

The primary presenting symptom of OSA is snoring, which is correlated with pauses in breathing. Risk factors include increased body mass index (BMI), thick neck circumference, male sex, and advanced age. In older adults, BMI has a lower impact on the Apnea-Hypopnea Index, an indicator of the number of pauses in breathing per hour, when compared with young and middle-age adults.16 Validated screening questionnaires for OSA include the STOP-Bang Questionnaire (Table 122), OSA50, Berlin Questionnaire, and Epworth Sleepiness Scale, each of which is used in different subpopulations. The current diagnostic standard for OSA is nocturnal polysomnography in a sleep laboratory, but recent advances in home sleep apnea testing have made it a viable, low-cost alternative for patients who do not have significant medical comorbidities.23 Standard utilized cutoffs for diagnosis are ≥5 events/hour (hypopneas associated with at least 4% oxygen desaturations) in conjunction with clinical symptoms of OSA.24

Continue to: Treatment

Treatment. First-line treatment for OSA is continuous positive airway pressure therapy, but adherence rates vary widely with patient education and regular follow-up.25 Adjunctive therapy includes weight loss, oral appliances, and uvulopalatopharyngoplasty, a procedure in which tissue in the throat is remodeled or removed.

Central sleep apnea (CSA) is a pause in breathing without evidence of associated respiratory effort. In adults, the development of CSA is indicative of underlying lower brainstem dysfunction, due to intermittent failures in the pontomedullary centers responsible for regulation of rhythmic breathing.26 This can occur as a consequence of multiple diseases, including congestive heart failure, stroke, renal failure, chronic medication use (opioids), and brain tumors.

The Sleep Heart Health Study—the largest community-based cohort study to date examining CSA—estimated that the prevalence of CSA among adults age >65 was 1.1% (compared with 0.4% in those age <65).27 Subgroup analysis revealed that men had significantly higher rates of CSA compared with women (2.7% vs 0.2%, respectively).

CSA may present similarly to OSA (excessive daytime somnolence, insomnia, poor sleep quality, difficulties with attention and concentration). Symptoms may also mimic those of coexisting medical conditions in older adults, such as nocturnal angina or paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea.27 Any older patient with daytime sleepiness and risk factors for CSA should be referred for in-laboratory nocturnal polysomnography, the gold standard diagnostic test. Unlike in OSA, ambulatory diagnostic measures (home sleep apnea testing) have not been validated for this disorder.27

Treatment. The primary treatment for CSA is to address the underlying medical problem. Positive pressure ventilation has been attempted with mixed results. Supplemental oxygen and medical management (acetazolamide or theophylline) can help stimulate breathing. Newer studies have shown favorable outcomes with transvenous neurostimulation or adaptive servoventilation.28-30

Continue to: Insomnia

Insomnia. For a primary diagnosis of insomnia, DSM-5 requires at least 3 nights per week of sleep disturbances that induce distress or functional impairment for at least 3 months.31 The International Classification of Disease, 10th Edition requires at least 1 month of symptoms (lying awake for a long time before falling asleep, sleeping for short periods, being awake for most of the night, feeling lack of sleep, waking up early) after ruling out other sleep disorders, substance use, or other medical conditions.4 Clinically, insomnia tends to present in older adults as a subjective complaint of dissatisfaction with the quality and/or quantity of their sleep. Insomnia has been consistently shown to be a significant risk factor for both the development or exacerbation of depression in older adults.32-34

While the diagnosis of insomnia is mainly clinical via a thorough sleep and medication history, assistive ancillary testing can include wrist actigraphy and screening questionnaires (the Insomnia Severity Index and the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index).4 Because population studies of older adults have found discrepancies between objective and subjective methods of assessing sleep quality, relying on the accuracy of self-reported symptoms alone is questionable.35

Treatment. Given that drug elimination half-life increases with age, and the risks of adverse effects are increased in older adults, the preferred treatment modalities for insomnia are nonpharmacologic.4 Sleep hygiene education (Table 2) and cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) for insomnia are often the first-line therapies.4,36,37 It is crucial to manage comorbidities such as heart disease and obesity, as well as sources of discomfort from conditions such as arthritic pain.38,39 If nonpharmacologic therapies are not effective, pharmacologic options can be considered.4 Before prescribing sleep medications, it may be more fruitful to treat underlying psychiatric disorders such as depression and anxiety with antidepressants.4 Although benzodiazepines are helpful for their sedative effects, they are not recommended for older adults because of an increased risk of falls, rebound insomnia, potential tolerance, and associated cognitive impairment.40 Benzodiazepine receptor agonists (eg, zolpidem, eszopiclone, zaleplon) were initially developed as a first-line treatment for insomnia to replace the reliance on benzodiazepines, but these medications have a “black-box” warning of a serious risk of complex sleep behaviors, including life-threatening parasomnias.41 As a result, guidelines suggest a shorter duration of treatment with a benzodiazepine receptor agonist may still provide benefit while limiting the risk of adverse effects.42

Doxepin is the only antidepressant FDA-approved for insomnia; it improves sleep latency (time taken to initiate sleep after lying down), duration, and quality in adults age >65.43 Melatonin receptor agonists such as ramelteon and melatonin have shown positive results in older patients with insomnia. In clinical trials of patients age ≥65, ramelteon, which is FDA-approved for insomnia, produced no rebound insomnia, withdrawal effects, memory impairment, or gait instability.44-46 Suvorexant, an orexin receptor antagonist, decreases sleep latency and increases total sleep time equally in both young and older adults.47-49Table 340-51 provides a list of medications used to treat insomnia (including off-label agents) and their common adverse effects in older adults.

Parasomnias are undesirable behaviors that occur during sleep, commonly associated with the sleep-wake transition period. These behaviors can occur during REM sleep (nightmare disorder, sleep paralysis, REM sleep behavior disorder) or NREM sleep (somnambulism [sleepwalking], confusional arousals, sleep terrors). According to a cross-sectional Norwegian study of parasomnias, the estimated lifetime prevalence of sleep walking is 22.4%; sleep talking, 66.8%; confusional arousal, 18.5%; and sleep terror, 10.4%.52

Continue to: When evaluating a patient...

When evaluating a patient with parasomnias, it is important to review their drug and substance use as well as coexisting medical conditions. Drugs and substances that can affect sleep include prescription medications (second-generation antidepressants, stimulants, dopamine agonists), excessive caffeine, alcohol, certain foods (coffee, chocolate milk, black tea, caffeinated soft drinks), environmental exposures (smoking, pesticides), and recreational drugs (amphetamines).53-56 Certain medical conditions are correlated with specific parasomnias (eg, sleep paralysis and narcolepsy, REM sleep behavior disorder and Parkinson’s disease [PD], etc.).54 Diagnosis of parasomnias is mainly clinical but supporting evidence can be obtained through in-lab polysomnography.

Treatment. For parasomnias, treatment is primarily supportive and includes creating a safe sleeping environment to reduce the risk of self-harm. Recommendations include sleeping in a room on the ground floor, minimizing furniture in the bedroom, padding any bedside furniture, child-proofing doorknobs, and locking up weapons and other dangerous household items.54

REM sleep behavior disorder (RBD). This disorder is characterized by a loss of the typical REM sleep-associated atonia and the presence of motor activity during dreaming (dream-enacted behaviors). While the estimated incidence of RBD in the general adult population is approximately 0.5%, it increases to 7.7% among those age >60.57 RBD occurs most commonly in the setting of the alpha-synucleinopathies (PD, Lewy body dementia, multisystem atrophy), but can also be found in patients with cerebral ischemia, demyelinating disorders, or alcohol misuse, or can be medication-induced (primarily antidepressants and antipsychotics).58 In patients with PD, the presence of RBD is associated with a more impaired cognitive profile, suggestive of widespread neurodegeneration.59 Recent studies revealed that RBD may also be a prodromal state of neurodegenerative diseases such as PD, which should prompt close monitoring and long-term follow up.60 Similar to other parasomnias, the diagnosis of RBD is primarily clinical, but polysomnography plays an important role in demonstrating loss of REM-related atonia.54

Treatment. Clonazepam and melatonin have been shown to be effective in treating the symptoms of RBD.54

Depression, anxiety, and sleep disturbances

Major depressive disorder (MDD) and generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) affect sleep in patients of all ages, but are underreported in older adults. According to national epidemiologic surveys, the estimated prevalence of MDD and GAD among older adults is 13% and 11.4%, respectively.61,62 Rates as high as 42% and 39% have been reported in meta-regression analyses among patients with Alzheimer’s dementia.63

Continue to: Depression and anxiety

Depression and anxiety may have additive effects and manifest as poor sleep satisfaction, increased sleep latency, insomnia, and daytime sleepiness.64 However, they may also have independent effects. Studies showed that patients with depression alone reported overall poor sleep satisfaction, whereas patients with anxiety alone reported problems with sleep latency, daytime drowsiness, and waking up at night in addition to their overall poor sleep satisfaction.65-67 Both depression and anxiety are risk factors for developing cognitive decline, and may be an early sign/prodrome of neurodegenerative diseases (dementias).68 The bidirectional relationship between depression/anxiety and sleep is complex and needs further investigation.

Treatment. Pharmacologic treatments for patients with depression/anxiety and sleep disturbances include selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, tricyclic antidepressants, and other serotonin receptor agonists.69-72 Nonpharmacologic treatments include CBT for both depression and anxiety, and problem-solving therapy for patients with mild cognitive impairment and depression.73,74 For severe depression and/or anxiety, electroconvulsive therapy is effective.75

Bottom Line

Sleep disorders in older adults are common but often underdiagnosed. Timely recognition of obstructive sleep apnea, central sleep apnea, insomnia, parasomnias, and other sleep disturbances can facilitate effective treatment and greatly improve older adults’ quality of life.

Related Resources

- American Academy of Sleep Medicine. International Classification of Sleep Disorders—Third Edition. https://aasm.org

- SleepFoundation.org. Sleep hygiene. https://www.sleepfoundation.org/articles/sleep-hygiene

Drug Brand Names

Acetazolamide • Diamox

Clonazepam • Klonopin

Doxepin • Silenor

Eszopiclone • Lunesta

Gabapentin • Neurontin

Mirtazapine • Remeron

Pramipexole • Mirapex

Quetiapine • Seroquel

Ramelteon • Rozerem

Suvorexant • Belsomra

Temazepam • Restoril

Theophylline • Elixophyllin

Tiagabine • Gabitril

Trazadone • Desyrel

Triazolam • Halcion

Zaleplon • Sonata

Zolpidem • Ambien

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The state of aging and health in America. 2013. Accessed January 27, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/aging/pdf/state-aging-health-in-america-2013.pdf

2. Suzuki K, Miyamoto M, Hirata K. Sleep disorders in the elderly: diagnosis and management. J Gen Fam Med. 2017;18(2):61-71.

3. Inouye SK, Studenski S, Tinetti ME, et al. Geriatric syndromes: clinical, research, and policy implications of a core geriatric concept. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55(5):780-791.

4. Patel D, Steinberg J, Patel P. Insomnia in the elderly: a review. J Clin Sleep Med. 2018;14(6):1017-1024.

5. Neubauer DN. A review of ramelteon in the treatment of sleep disorders. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2008;4(1):69-79.

6. Mander BA, Winer JR, Walker MP. Sleep and human aging. Neuron. 2017;94(1):19-36.

7. Ohayon MM, Carskadon MA, Guilleminault C, et al. Meta-analysis of quantitative sleep parameters from childhood to old age in healthy individuals: developing normative sleep values across the human lifespan. Sleep. 2004;27:1255-1273.

8. Li J, Vitiello MV, Gooneratne NS. Sleep in normal aging. Sleep Med Clin. 2018;13(1):1-11.

9. Floyd JA, Medler SM, Ager JW, et al. Age-related changes in initiation and maintenance of sleep: a meta-analysis. Res Nurs Health. 2000;23(2):106-117.

10. Floyd JA, Janisse JJ, Jenuwine ES, et al. Changes in REM-sleep percentage over the adult lifespan. Sleep. 2007;30(7):829-836.

11. Dorffner G, Vitr M, Anderer P. The effects of aging on sleep architecture in healthy subjects. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2015;821:93-100.

12. Furihata R, Kaneita Y, Jike M, et al. Napping and associated factors: a Japanese nationwide general population survey. Sleep Med. 2016;20:72-79.

13. Foley DJ, Vitiello MV, Bliwise DL, et al. Frequent napping is associated with excessive daytime sleepiness, depression, pain, and nocturia in older adults: findings from the National Sleep Foundation ‘2003 Sleep in America’ Poll. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007;15(4):344-350.

14. Floyd JA, Janisse JJ, Marshall Medler S, et al. Nonlinear components of age-related change in sleep initiation. Nurs Res. 2000;49(5):290-294.

15. Miner B, Kryger MH. Sleep in the aging population. Sleep Med Clin. 2017;12(1):31-38.

16. Young T, Peppard PE, Gottlieb DJ. Epidemiology of obstructive sleep apnea: a population health perspective. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;165(9):1217-1239.

17. Ancoli-Israel S, Klauber MR, Butters N, et al. Dementia in institutionalized elderly: relation to sleep apnea. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1991;39(3):258-263.

18. Spira AP, Stone KL, Rebok GW, et al. Sleep-disordered breathing and functional decline in older women. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62(11):2040-2046.

19. Vijayan VK. Morbidities associated with obstructive sleep apnea. Expert Rev Respir Med. 2012;6(5):557-566.

20. Kerner NA, Roose SP. Obstructive sleep apnea is linked to depression and cognitive impairment: evidence and potential mechanisms. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2016;24(6):496-508.

21. Dalmases M, Solé-Padullés C, Torres M, et al. Effect of CPAP on cognition, brain function, and structure among elderly patients with OSA: a randomized pilot study. Chest. 2015;148(5):1214-1223.

22. Toronto Western Hospital, University Health Network. University of Toronto. STOP-Bang Questionnaire. 2012. Accessed January 26, 2021. www.stopbang.ca

23. Freedman N. Doing it better for less: incorporating OSA management into alternative payment models. Chest. 2019;155(1):227-233.

24. Kapur VK, Auckley DH, Chowdhuri S, et al. Clinical practice guideline for diagnostic testing for adult obstructive sleep apnea: an American Academy of Sleep Medicine clinical practice guideline. J Clin Sleep Med. 2017;13(3):479-504.

25. Semelka M, Wilson J, Floyd R. Diagnosis and treatment of obstructive sleep apnea in adults. Am Fam Physician. 2016;94(5):355-360.

26. Javaheri S, Dempsey JA. Central sleep apnea. Compr Physiol. 2013;3(1):141-163.

27. Donovan LM, Kapur VK. Prevalence and characteristics of central compared to obstructive sleep apnea: analyses from the Sleep Heart Health Study cohort. Sleep. 2016;39(7):1353-1359.

28. Cao M, Cardell CY, Willes L, et al. A novel adaptive servoventilation (ASVAuto) for the treatment of central sleep apnea associated with chronic use of opioids. J Clin Sleep Med. 2014;10(8):855-861.

29. Oldenburg O, Spießhöfer J, Fox H, et al. Performance of conventional and enhanced adaptive servoventilation (ASV) in heart failure patients with central sleep apnea who have adapted to conventional ASV. Sleep Breath. 2015;19(3):795-800.

30. Costanzo MR, Ponikowski P, Javaheri S, et al. Transvenous neurostimulation for central sleep apnoea: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2016;388(10048):974-982.

31. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association; 2013:362.

32. Perlis ML, Smith LJ, Lyness JM, et al. Insomnia as a risk factor for onset of depression in the elderly. Behav Sleep Med. 2006;4(2):104-113.

33. Cole MG, Dendukuri N. Risk factors for depression among elderly community subjects: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(6):1147-1156.

34. Pigeon WR, Hegel M, Unützer J, et al. Is insomnia a perpetuating factor for late-life depression in the IMPACT cohort? Sleep. 2008;31(4):481-488.

35. Hughes JM, Song Y, Fung CH, et al. Measuring sleep in vulnerable older adults: a comparison of subjective and objective sleep measures. Clin Gerontol. 2018;41(2):145-157.

36. Irish LA, Kline CE, Gunn HE, et al. The role of sleep hygiene in promoting public health: a review of empirical evidence. Sleep Med Rev. 2015;22:23-36.

37. Sleep Foundation. Sleep hygiene. Accessed January 27, 2021. https://www.sleepfoundation.org/articles/sleep-hygiene

38. Foley D, Ancoli-Israel S, Britz P, et al. Sleep disturbances and chronic disease in older adults: results of the 2003 National Sleep Foundation Sleep in America Survey. J Psychosom Res. 2004;56(5):497-502.

39. Eslami V, Zimmerman ME, Grewal T, et al. Pain grade and sleep disturbance in older adults: evaluation the role of pain, and stress for depressed and non-depressed individuals. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2016;31(5):450-457.

40. American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society 2015 updated Beers Criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63(11):2227-2246.

41. United States Food & Drug Administration. FDA adds Boxed Warning for risk of serious injuries caused by sleepwalking with certain prescription insomnia medicines. 2019. Accessed January 27, 2021. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/fda-adds-boxed-warning-risk-serious-injuries-caused-sleepwalking-certain-prescription-insomnia

42. Schroeck JL, Ford J, Conway EL, et al. Review of safety and efficacy of sleep medicines in older adults. Clin Ther. 2016;38(11):2340-2372.

43. Krystal AD, Lankford A, Durrence HH, et al. Efficacy and safety of doxepin 3 and 6 mg in a 35-day sleep laboratory trial in adults with chronic primary insomnia. Sleep. 2011;34(10):1433-1442.

44. Roth T, Seiden D, Sainati S, et al. Effects of ramelteon on patient-reported sleep latency in older adults with chronic insomnia. Sleep Med. 2006;7(4):312-318.

45. Zammit G, Wang-Weigand S, Rosenthal M, et al. Effect of ramelteon on middle-of-the-night balance in older adults with chronic insomnia. J Clin Sleep Med. 2009;5(1):34-40.

46. Mets MAJ, de Vries JM, de Senerpont Domis LM, et al. Next-day effects of ramelteon (8 mg), zopiclone (7.5 mg), and placebo on highway driving performance, memory functioning, psychomotor performance, and mood in healthy adult subjects. Sleep. 2011;34(10):1327-1334.

47. Rhyne DN, Anderson SL. Suvorexant in insomnia: efficacy, safety and place in therapy. Ther Adv Drug Saf. 2015;6(5):189-195.

48. Norman JL, Anderson SL. Novel class of medications, orexin receptor antagonists, in the treatment of insomnia - critical appraisal of suvorexant. Nat Sci Sleep. 2016;8:239-247.

49. Owen RT. Suvorexant: efficacy and safety profile of a dual orexin receptor antagonist in treating insomnia. Drugs Today (Barc). 2016;52(1):29-40.

50. Shannon S, Lewis N, Lee H, et al. Cannabidiol in anxiety and sleep: a large case series. Perm J. 2019;23:18-041. doi: 10.7812/TPP/18-041

51. Yunusa I, Alsumali A, Garba AE, et al. Assessment of reported comparative effectiveness and safety of atypical antipsychotics in the treatment of behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia: a network meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(3):e190828.

52. Bjorvatn B, Gronli J, Pallesen S. Prevalence of different parasomnias in the general population. Sleep Med. 2010;11(10):1031-1034.

53. Postuma RB, Montplaisir JY, Pelletier A, et al. Environmental risk factors for REM sleep behavior disorder: a multicenter case-control study. Neurology. 2012;79(5):428-434.

54. Fleetham JA, Fleming JA. Parasomnias. CMAJ. 2014;186(8):E273-E280.

55. Dinis-Oliveira RJ, Caldas I, Carvalho F, et al. Bruxism after 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (ecstasy) abuse. Clin Toxicol (Phila.) 2010;48(8):863-864.

56. Irfan MH, Howell MJ. Rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder: overview and current perspective. Curr Sleep Medicine Rep. 2016;2:64-73.

57. Mahlknecht P, Seppi K, Frauscher B, et al. Probable RBD and association with neurodegenerative disease markers: a population-based study. Mov Disord. 2015;30(10):1417-1421.

58. Oertel WH, Depboylu C, Krenzer M, et al. [REM sleep behavior disorder as a prodromal stage of α-synucleinopathies: symptoms, epidemiology, pathophysiology, diagnosis and therapy]. Nervenarzt. 2014;85:19-25. German.

59. Jozwiak N, Postuma RB, Montplaisir J, et al. REM sleep behavior disorder and cognitive impairment in Parkinson’s disease. Sleep. 2017;40(8):zsx101. doi: 10.1093/sleep/zsx101

60. Claassen DO, Josephs KA, Ahlskog JE, et al. REM sleep behavior disorder preceding other aspects of synucleinopathies by up to half a century. Neurology 2010;75(6):494-499.

61. Reynolds K, Pietrzak RH, El-Gabalawy R, et al. Prevalence of psychiatric disorders in U.S. older adults: findings from a nationally representative survey. World Psychiatry. 2015;14(1):74-81.

62. Lohman MC, Mezuk B, Dumenci L. Depression and frailty: concurrent risks for adverse health outcomes. Aging Ment Health. 2017;21(4):399-408.