User login

On January 1, 2014, several major provisions of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) took effect, including introduction of the individual mandate for health insurance coverage, opening of the Health Insurance Marketplace, and expansion of Medicaid eligibility to Americans earning up to 133% of the federal poverty level.[1] Nearly 9 million US adults have enrolled in Medicaid since that time, primarily in the 31 states and Washington, DC that have opted into Medicaid expansion.[2, 3] ACA implementation has also had a significant impact on hospital payer mix, primarily by reducing the volume of uncompensated care in Medicaid‐expansion states.[4, 5]

The differential shift in payer mix in Medicaid‐expansion versus nonexpansion states may be relevant to hospitals beyond reimbursement. Medicaid insurance has historically been associated with longer hospitalizations and higher in‐hospital mortality in diverse patient populations, more so than commercial insurance and often even uninsured payer status.[6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15] The disparity in outcomes between patients with Medicaid versus other insurance persists even after adjustment for disease severity and baseline comorbidities. Insurance type may influence the delivery of inpatient care through variation in access to invasive procedures and adherence to guideline‐concordant medical therapies.[9, 10, 11, 12] Medicaid patients may be more likely than uninsured patients to remain hospitalized pending postacute care placement rather than be discharged home with family support.[16] Medicaid patients are also less likely to leave against medical advice than uninsured patients.[17]

Currently, little is known about the impact of state Medicaid expansion status on length of stay (LOS) or mortality nationally. It is possible that hospitals in Medicaid‐expansion states have experienced relative worsening in LOS and mortality as their share of Medicaid patients has grown. Determining the impact of ACA implementation on payer mix and patient outcomes is particularly important for academic medical centers (AMCs), as they traditionally care for the greatest percentage of both Medicaid and uninsured patients.[18] We sought to characterize the impact of state Medicaid expansion status on payer mix, LOS, and in‐hospital mortality for general medicine patients at AMCs in the United States.

METHODS

The University HealthSystem Consortium (UHC) is an alliance of 117 AMCs and 310 affiliated hospitals, representing >90% of such institutions in the US. We queried the online UHC Clinical Data Base/Resource Manager (CDB/RM) to obtain hospital‐level insurance, LOS, and mortality data for inpatients discharged from a general medicine service between October 1, 2012 and September 30, 2015. We excluded hospitals that were missing data for any month within the study period. No patient‐level data were accessed.

Our outcomes of interest were the proportion of discharges by primary payer (Medicare, commercial, Medicaid, uninsured, or other [eg, Tri‐Care or Workers' Compensation]), as well as the LOS index and mortality index. Both indices were defined as the ratio of the observed to expected values. To determine the expected LOS and mortality, the UHC 2015 risk adjustment models were applied to all cases, adjusting for variables such as patient demographics, low socioeconomic status, admit source and status, severity of illness, and comorbid conditions, as described by International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision codes. These models have been validated and are used for research and quality benchmarking for member institutions.[19]

We next stratified hospitals according to state Medicaid expansion status. We defined Medicaid‐expansion states as those that had expanded Medicaid by the end of the study period: Arizona, Arkansas, California, Colorado, Connecticut, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kentucky, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, Nevada, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, Ohio, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, Washington, Washington DC, and West Virginia. Nonexpansion states included Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Kansas, Louisiana, Missouri, Nebraska, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, Utah, Virginia, and Wisconsin. We excluded 12 states due to incomplete data: Alaska, Delaware, Hawaii, Idaho, North Dakota, Maine, Mississippi, Montana, Oklahoma, South Dakota, Vermont, and Wyoming.

We then identified our pre‐ and post‐ACA implementation periods. Medicaid coverage expansion took effect in all expansion states on January 1, 2014, with the exception of Michigan (April 1, 2014), New Hampshire (August 15, 2014), Pennsylvania (January 1, 2015), and Indiana (February 1, 2015).[3] We therefore defined October 1, 2012 to December 31, 2013 as the pre‐ACA implementation period and January 1, 2014 to September 30, 2015 as the post‐ACA implementation period for all states except for Michigan, New Hampshire, Pennsylvania, and Indiana. For these 4 states, we customized the pre‐ and post‐ACA implementation periods to their respective dates of Medicaid expansion; for New Hampshire, we designated October 1, 2012 to July 31, 2014 as the pre‐ACA implementation period and September 1, 2014 to September 30, 2015 as the post‐ACA implementation period, as we were unable to distinguish before versus after data in August 2014 based on the midmonth expansion of Medicaid.

After stratifying hospitals into groups based on whether they were located in Medicaid‐expansion or nonexpansion states, the proportion of discharges by payer was compared between pre‐ and post‐ACA implementation periods both graphically by quarter and using linear regression models weighted for the number of cases from each hospital. Next, for both Medicaid‐expansion and nonexpansion hospitals, LOS index and mortality index were compared before and after ACA implementation using linear regression models weighted for the number of cases from each hospital, both overall and by payer. Difference‐in‐differences estimations were then completed to compare the proportion of discharges by payer, LOS index, and mortality index between Medicaid‐expansion and nonexpansion hospitals before and after ACA implementation. Post hoc linear regression analyses were completed to evaluate the effect of clustering by state level strata on payer mix and LOS and mortality indices. A 2‐sided P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Data analyses were performed using Stata 12.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

RESULTS

We identified 4,258,952 discharges among general medicine patients from 211 hospitals in 38 states and Washington, DC between October 1, 2012, and September 30, 2015. This included 3,144,488 discharges from 156 hospitals in 24 Medicaid‐expansion states and Washington, DC and 1,114,464 discharges from 55 hospitals in 14 nonexpansion states.

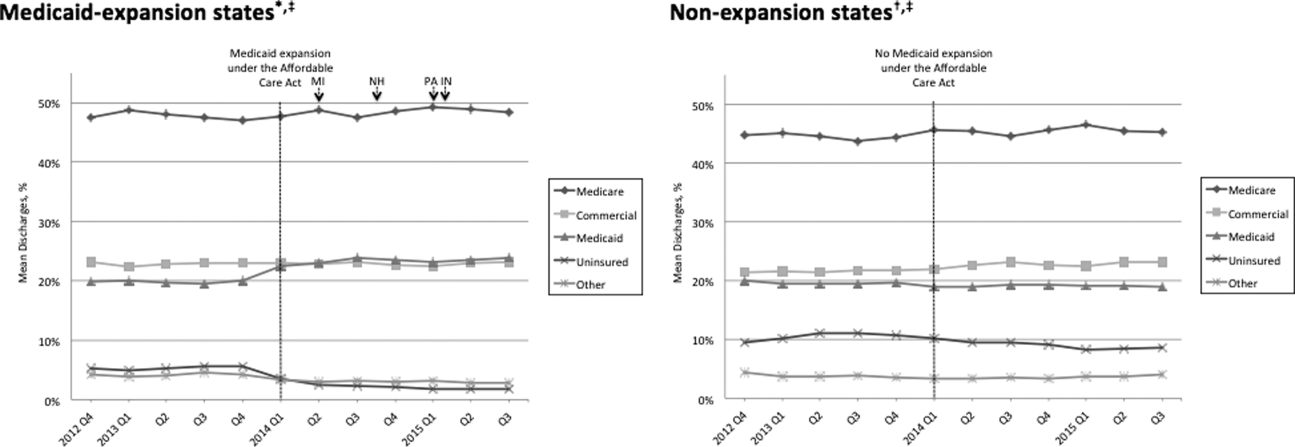

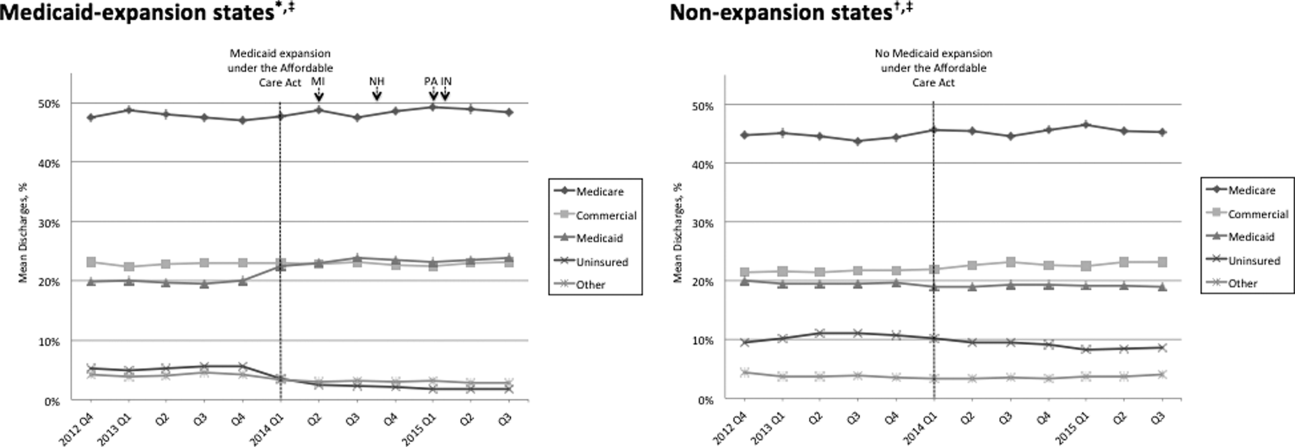

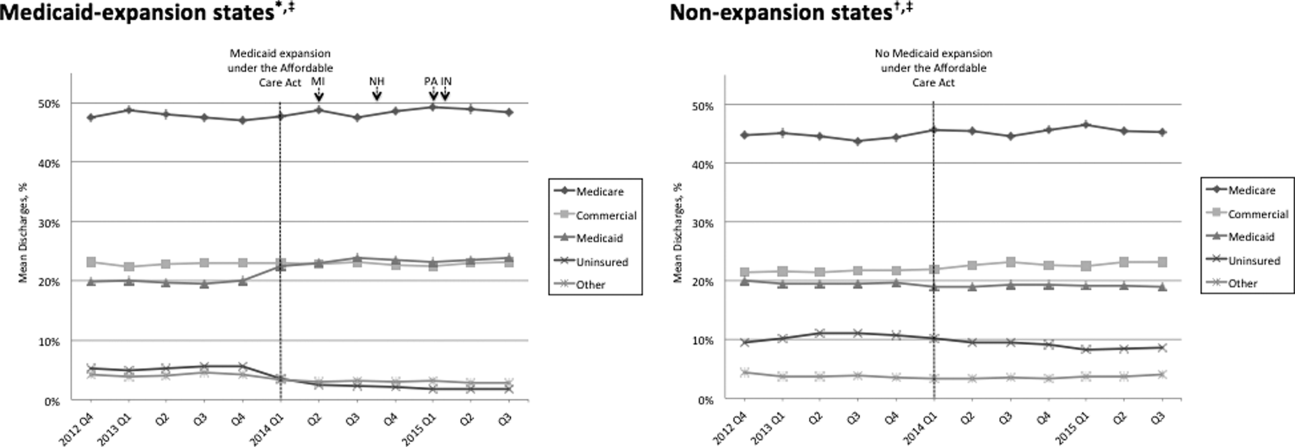

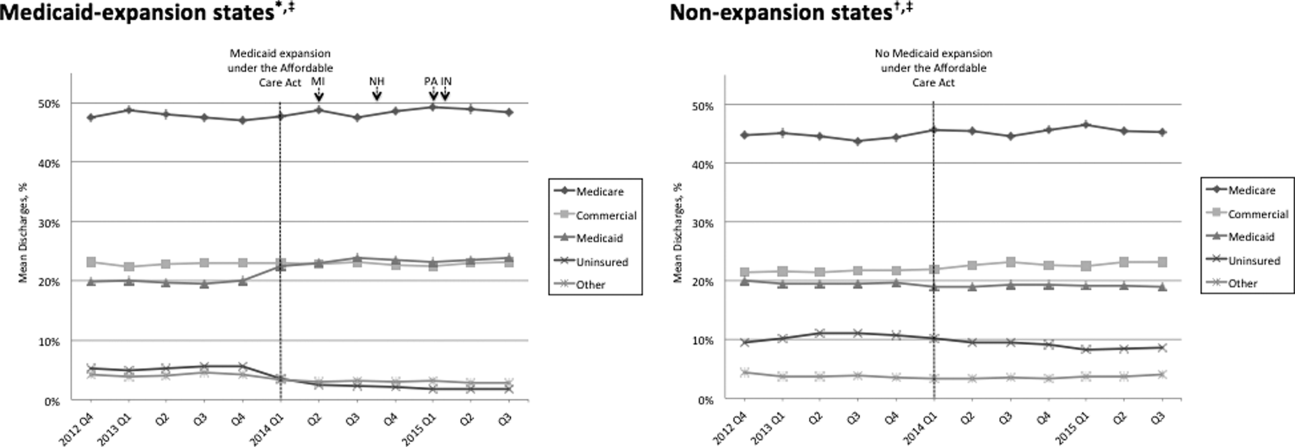

Figure 1 shows the trends in payer mix over time for hospitals in both Medicaid‐expansion and nonexpansion states. As summarized in Table 1, hospitals in Medicaid‐expansion states experienced a significant 3.7‐percentage point increase in Medicaid discharges (P = 0.013) and 2.9‐percentage point decrease in uninsured discharges (P < 0.001) after ACA implementation. This represented an approximately 19% jump and 60% drop in Medicaid and uninsured discharges, respectively. Hospitals in nonexpansion states saw no significant change in the proportion of discharges by payer after ACA implementation. In the difference‐in‐differences analysis, there was a trend toward a greater change in the proportion of Medicaid discharges pre‐ to post‐ACA implementation among hospitals in Medicaid‐expansion states compared to hospitals in nonexpansion states (mean difference‐in‐differences 4.1%, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.3%, 8.6%, P = 0.070).

| Medicaid‐expansion n=156 hospitals; 3,144,488 cases | Non‐expansion n=55 hospitals; 1,114,464 cases | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre‐ACA Implementation (1,453,090 Cases) | Post‐ACA Implementation (1,691,398 Cases) | Mean Difference | P Value | Pre‐ACA Implementation (455,440 Cases) | Post‐ACA Implementation (659,024 Cases) | Mean Difference | P Value | Mean Difference‐in‐Differences | P Value | |

| ||||||||||

| Payer mix, % (95% CI) | ||||||||||

| Medicare | 48.6 (46.2, 51.0)* | 48.3 (45.9, 50.7) | 0.3 (3.6, 3.1) | 0.865 | 44.3 (40.7, 47.7)* | 45.3 (41.9, 48.6) | 1.0 (3.8, 5.8) | 0.671 | 1.3 (7.1, 4.5) | 0.655 |

| Commercial | 23.1 (21.4, 24.7) | 23.2 (21.8, 24.6) | 0.2 (2.0, 2.3) | 0.882 | 21.5 (18.5, 24.6) | 22.7 (19.7, 25.8) | 1.2 (3.0, 5.4) | 0.574 | 1.0 (5.7, 3.6) | 0.662 |

| Medicaid | 19.6 (17.6, 21.6) | 23.3 (21.2, 25.5) | 3.7 (0.8, 6.6) | 0.013 | 19.4 (16.9, 21.9) | 19.0 (16.5, 21.4) | 0.4 (3.8, 3.0) | 0.812 | 4.1 (0.3, 8.6) | 0.070 |

| Uninsured | 5.0 (4.0, 5.9) | 2.0 (1.7, 2.3) | 2.9 (3.9, 2.0) | <0.001 | 10.9 (8.1, 13.7) | 9.4 (7.0, 11.7) | 1.5 (5.1, 2.1) | 0.407 | 1.4 (5.1, 2.2) | 0.442 |

| Other | 3.8 (2.6, 4.9) | 3.1 (2.0, 4.3) | 0.7 (2.3, 1.0) | 0.435 | 4.0 (2.9, 5.0) | 3.7 (2.6, 4.7) | 0.3 (1.7, 1.1) | 0.662 | 0.3 (2.5, 1.8) | 0.762 |

| LOS index, mean (95% CI) | ||||||||||

| Overall | 1.017 (0.996, 1.038) | 1.006 (0.981, 1.031) | 0.011 (0.044, 0.021) | 0.488 | 1.008 (0.974, 1.042) | 0.995 (0.961, 1.029) | 0.013 (0.061, 0.034) | 0.574 | 0.002 (0.055, 0.059) | 0.943 |

| Medicare | 1.012 (0.989, 1.035) | 0.999 (0.971, 1.027) | 0.013 (0.049, 0.023) | 0.488 | 0.982 (0.946, 1.017) | 0.979 (0.944, 1.013) | 0.003 (0.052, 0.046) | 0.899 | 0.010 (0.070, 0.051) | 0.754 |

| Commercial | 0.993 (0.974, 1.012) | 0.977 (0.955, 0.998) | 0.016 (0.045, 0.013) | 0.271 | 1.009 (0.978, 1.039) | 0.986 (0.956, 1.016) | 0.022 (0.065, 0.020) | 0.298 | 0.006 (0.044, 0.057) | 0.809 |

| Medicaid | 1.059 (1.036, 1.082) | 1.043 (1.018, 1.067) | 0.016 (0.049, 0.017) | 0.349 | 1.064 (1.020, 1.108) | 1.060 (1.015, 1.106) | 0.004 (0.066, 0.059) | 0.911 | 0.012 (0.082, 0.057) | 0.727 |

| Uninsured | 0.960 (0.933, 0.988) | 0.925 (0.890, 0.961) | 0.035 (0.080, 0.010) | 0.126 | 0.972 (0.935, 1.009) | 0.944 (0.909, 0.979) | 0.028 (0.078, 0.022) | 0.273 | 0.007 (0.074, 0.060) | 0.835 |

| Other | 0.988 (0.960, 1.017) | 0.984 (0.952, 1.015) | 0.005 (0.047, 0.037) | 0.822 | 1.022 (0.973, 1.071) | 0.984 (0.944, 1.024) | 0.038 (0.100, 0.024) | 0.232 | 0.033 (0.042, 0.107) | 0.386 |

| Mortality index, mean (95% CI) | ||||||||||

| Overall | 1.000 (0.955, 1.045) | 0.878 (0.836, 0.921) | 0.122 (0.183, 0.061) | <0.001 | 0.997 (0.931, 1.062) | 0.850 (0.800, 0.900) | 0.147 (0.227, 0.066) | 0.001 | 0.025 (0.076, 0.125) | 0.628 |

| Medicare | 0.990 (0.942, 1.038) | 0.871 (0.826, 0.917) | 0.119 (0.185, 0.053) | <0.001 | 1.000 (0.925, 1.076) | 0.844 (0.788, 0.900) | 0.156 (0.249, 0.064) | 0.001 | 0.038 (0.075, 0.150) | 0.513 |

| Commercial | 1.045 (0.934, 1.155) | 0.908 (0.842, 0.975) | 0.136 (0.264, 0.008) | 0.037 | 1.023 (0.935, 1.111) | 0.820 (0.758, 0.883) | 0.203 (0.309, 0.096) | <0.001 | 0.067 (0.099, 0.232) | 0.430 |

| Medicaid | 0.894 (0.845, 0.942) | 0.786 (0.748, 0.824) | 0.107 (0.168, 0.046) | 0.001 | 0.937 (0.861, 1.013) | 0.789 (0.733, 0.844) | 0.148 (0.242, 0.055) | 0.002 | 0.041 (0.069, 0.151) | 0.464 |

| Uninsured | 1.172 (1.007, 1.337)∥ | 1.136 (0.968, 1.303) | 0.037 (0.271, 0.197) | 0.758 | 0.868 (0.768, 0.968)∥ | 0.850 (0.761, 0.939) | 0.017 (0.149, 0.115) | 0.795 | 0.019 (0.287, 0.248) | 0.887 |

| Other | 1.376 (1.052, 1.700)# | 1.156 (0.910, 1.402) | 0.220 (0.624, 0.184) | 0.285 | 1.009 (0.868, 1.150) # | 0.874 (0.682, 1.066) | 0.135 (0.369, 0.099) | 0.254 | 0.085 (0.555, 0.380) | 0.720 |

Table 1 shows that the overall LOS index remained unchanged pre‐ to post‐ACA implementation for both Medicaid‐expansion (1.017 to 1.006, P = 0.488) and nonexpansion hospitals (1.008 to 0.995, P = 0.574). LOS indices for each payer type also remained unchanged. The overall mortality index significantly improved pre‐ to post‐ACA implementation for both Medicaid‐expansion (1.000 to 0.878, P < 0.001) and nonexpansion hospitals (0.997 to 0.850, P = 0.001). Among both Medicaid‐expansion and nonexpansion hospitals, the mortality index significantly improved for Medicare, commercial, and Medicaid discharges but not for uninsured or other discharges. In the difference‐in‐differences analysis, the changes in LOS indices and mortality indices pre‐ to post‐ACA implementation did not differ significantly between hospitals in Medicaid‐expansion versus nonexpansion states.

In post hoc linear regression analyses of payer mix and LOS and mortality indices clustered by state‐level strata, point estimates were minimally changed. Although 95% CIs were slightly wider, statistical significance was unchanged from our primary analyses (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

We found that ACA implementation had a significant impact on payer mix for general medicine patients at AMCs in the United States, primarily by increasing the number of Medicaid beneficiaries and by decreasing the number of uninsured patients in Medicaid‐expansion states. State Medicaid expansion status did not appear to influence either LOS or in‐hospital mortality.

Our study offers some of the longest‐term data currently available on the impact of ACA implementation on payer mix trends and encompasses more states than others have previously. Although we uniquely focused on general medicine patients at AMCs, our results are similar to those seen for US hospitals overall. Nikpay and colleagues evaluated payer mix trends for non‐Medicare adult inpatient stays in 16 states through the second quarter of 2014 using the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project database through the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.[4] They found a relative 20% increase and 50% decrease in Medicaid and uninsured discharges in Medicaid‐expansion states, along with nonsignificant changes in nonexpansion states. Hempstead and Cantor assessed payer mix for non‐Medicare discharges using state hospital association data from 21 states through the fourth quarter of 2014 and found a significant increase in Medicaid patients as well as a nearly significant decrease in uninsured patients in expansion states relative to nonexpansion states.[5] The Department of Health and Human Services also reported that uninsured/self‐pay discharges fell substantially (65%73%) in Medicaid‐expansion states by the end of 2014, with slight decreases in nonexpansion states.[20]

In contrast to our hypothesis, the overall LOS and in‐hospital mortality indices were not influenced by state Medicaid expansion status. From a purely mathematical standpoint, the contribution of Medicaid patients to the overall LOS and mortality indices may have been eclipsed by Medicare and commercially insured patients, who represented a higher proportion of total discharges. The lack of impact of state Medicaid expansion status on overall LOS and mortality indices did not appear to occur as a result of indices for Medicaid patients trending toward the mean. As predicted based on observational studies, Medicaid patients in our study tended to have a higher LOS index than those with other insurance types. Medicaid patients actually tended to have a lower mortality index in our analysis; the reason for this latter finding is unclear and in contrast to other published studies.[6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 21]

To our knowledge, no other studies have evaluated the effect of payer mix changes under the ACA on inpatient outcomes. However, new evidence is emerging on outpatient outcomes. Low‐income adults in Medicaid‐expansion states have reported greater gains in access to primary care services and in the diagnosis of certain chronic health conditions than those in nonexpansion states as a result of ACA implementation.[22, 23] Such improvements in the outpatient setting might be expected to reduce patient acuity on admission. However, they would not necessarily translate to relative improvements in LOS or mortality indices for Medicaid‐expansion hospitals, as the UHC risk adjustment models controlled for disease severity on admission.

Similarly, few studies have assessed the impact of payer mix changes under previous state Medicaid expansions on inpatient outcomes. After Massachusetts expanded Medicaid and enacted near‐universal healthcare coverage in 2006, a minimal LOS reduction of just 0.05 days was observed.[24] New York expanded Medicaid eligibility to nondisabled childless adults with incomes below 100% of the federal poverty level in September 2001, whereas Arizona did so in November 2001 and Maine in October 2002. A study comparing outcomes in these states to 4 neighboring nonexpansion states found a relative reduction in annual all‐cause mortality of 6.1% population wide; however, it did not assess in‐hospital mortality.[25] The Oregon Health Insurance Experiment that randomized low‐income adults to expanded Medicaid coverage or not in 2008 has also reported on outpatient rather than inpatient outcomes.[26]

Our findings have potential implications for health policymakers. That Medicaid expansion status had a neutral effect on both LOS and mortality indices in our analysis should be reassuring for states contemplating Medicaid expansion in the future. Our results also highlight the need for further efforts to reduce disparities in inpatient care based on payer status. For example, although Medicare, commercially insured, and Medicaid patients witnessed significant improvements in mortality indices pre‐ to post‐ACA implementation in hospitals in both Medicaid‐expansion and nonexpansion states, uninsured patients did not.

This study has several limitations. First, our analysis of the impact of ACA implementation on payer mix did not account for concurrent socioeconomic trends that may have influenced insurance coverage across the United States. However, the main goal of this analysis was to demonstrate that changes in payer mix did in fact occur over time, to provide rationale for our subsequent LOS and mortality analyses. Second, we could not control for variation in the design and implementation of Medicaid expansions across states as permitted under the federal Section 1115 waiver process. Third, we only had access to hospital‐level data through the UHC CDB/RM, rather than individual patient data. We attempted to mitigate this limitation by weighting data according to the number of cases per hospital. Lastly, additional patient‐level factors that may influence LOS or mortality may not be included in the UHC risk adjustment models.

In summary, the differential shift in payer mix between Medicaid‐expansion and nonexpansion states did not influence overall LOS or in‐hospital mortality for general medicine patients at AMCs in the United States. Additional research could help to determine the impact of ACA implementation on other patient outcomes that may be dependent on insurance status, such as readmissions or hospital‐acquired complications.

Disclosures: M.E.A. conceived of the study concept and design, assisted with data acquisition, and drafted the manuscript. J.J.G. assisted with study design and made critical revisions to the manuscript. D.A. assisted with study design and made critical revisions to the manuscript. R.P. assisted with study design and made critical revisions to the manuscript. M.L. assisted with study design and data acquisition and made critical revisions to the manuscript. C.D.J. assisted with study design, performed data analyses, and made critical revisions to the manuscript. A modified abstract was presented in poster format at the University HealthSystem Consortium Annual Conference held September 30 to October 2, 2015 in Orlando, Florida, as well as at the Society of Hospital Medicine Research, Innovations, and Vignettes 2016 Annual Meeting held March 69, 2016, in San Diego, California. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

- Department of Health and Human Services. Key features of the Affordable Care Act by year. Available at: http://www.hhs.gov/healthcare/facts‐and‐features/key‐features‐of‐aca‐by‐year/index.html#2014. Accessed April 4, 2016.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicaid enrollment data collected through MBES. Available at: https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid‐chip‐program‐information/program‐information/medicaid‐and‐chip‐enrollment‐data/medicaid‐enrollment‐data‐collected‐through‐mbes.html. Accessed April 4, 2016.

- The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. Status of state action on the Medicaid expansion decision. Available at: http://kff.org/health‐reform/state‐indicator/state‐activity‐around‐expanding‐medicaid‐under‐the‐affordable‐care‐act. Accessed April 4, 2016.

- , , . Affordable Care Act Medicaid expansion reduced uninsured hospital stays in 2014. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35(1):106–110.

- , . State Medicaid expansion and changes in hospital volume according to payer. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(2):196–198.

- , , , , , . Understanding predictors of prolonged hospitalizations among general medicine patients: a guide and preliminary analysis. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(9):623–626.

- , , , . Impact of insurance and hospital ownership on hospital length of stay among patients with ambulatory care‐sensitive conditions. Ann Fam Med. 2011;9:489–495.

- , , . Insurance status and hospital care for myocardial infarction, stroke, and pneumonia. J Hosp Med. 2010;5:452–459.

- , , , , , . Payment source, quality of care, and outcomes in patients hospitalized with heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58(14):1465–1471.

- , , , , . The inpatient experience and predictors of length of stay for patients hospitalized with systolic heart failure: comparison by commercial, Medicaid, and Medicare payer type. J Med Econ. 2013;16(1):43–54.

- , , et al. Insurance coverage and care of patients with non‐ST‐segment elevation acute coronary syndromes. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145:739–748.

- , , , et al. Association of insurance status with inpatient treatment for coronary artery disease: findings from the Get with the Guidelines Program. Am Heart J. 2010;159:1026–1036.

- , , , et al. Primary payer status affects mortality for major surgical operations. Ann Surg. 2010;252:544–551.

- , , . Medicaid payer status is associated with in‐hospital morbidity and resource utilization following primary total joint arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96(21):e180.

- , , . The quality of care delivered to patients within the same hospital varies by insurance type. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32(10):1731–1739.

- , , , , . Effect of insurance status on postacute care among working age stroke survivors. Neurology. 2012;78(20):1590–1595.

- , , , . Hospitalizations in which patients leave the hospital against medical advice (AMA), 2007. HCUP statistical brief #78. August 2009. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2009. Available at: http://www.hcup‐us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb78.pdf. Accessed May 12, 2016.

- , , , . Characteristics of Medicaid and uninsured hospitalizations, 2012. HCUP statistical brief #182. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2014. Available at: http://www.hcup‐us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb182‐Medicaid‐Uninsured‐Hospitalizations‐2012.pdf. Accessed March 9, 2016.

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Mortality measurement: mortality risk adjustment methodology for University HealthSystem Consortium. Available at: http://archive.ahrq.gov/professionals/quality‐patient‐safety/quality‐resources/tools/mortality/Meurer.pdf. Accessed May 10, 2016.

- Department of Health and Human Services. Insurance expansion, hospital uncompensated care, and the Affordable Care Act. Available at: https://aspe.hhs.gov/pdf‐report/insurance‐expansion‐hospital‐uncompensated‐care‐and‐affordable‐care‐act. Accessed May 27, 2016.

- , , , . Our flawed but beneficial Medicaid program. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(16):e31.

- , , , . Changes in self‐reported insurance coverage, access to care, and health under the Affordable Care Act. JAMA. 2015;314(4):366–374.

- , . Early coverage, access, utilization, and health effects associated with the Affordable Care Act Medicaid Expansions: a quasi‐experimental study. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164(12):795–803.

- , . The impact of health care reform on hospital and preventive care: evidence from Massachusetts. J Public Econ. 2012;96(11–12):909–929.

- , , . Mortality and access to care among adults after state Medicaid expansions. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1025–1034.

- , , , et al. The Oregon Experiment—effects of Medicaid on clinical outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(18):1713–1722.

On January 1, 2014, several major provisions of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) took effect, including introduction of the individual mandate for health insurance coverage, opening of the Health Insurance Marketplace, and expansion of Medicaid eligibility to Americans earning up to 133% of the federal poverty level.[1] Nearly 9 million US adults have enrolled in Medicaid since that time, primarily in the 31 states and Washington, DC that have opted into Medicaid expansion.[2, 3] ACA implementation has also had a significant impact on hospital payer mix, primarily by reducing the volume of uncompensated care in Medicaid‐expansion states.[4, 5]

The differential shift in payer mix in Medicaid‐expansion versus nonexpansion states may be relevant to hospitals beyond reimbursement. Medicaid insurance has historically been associated with longer hospitalizations and higher in‐hospital mortality in diverse patient populations, more so than commercial insurance and often even uninsured payer status.[6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15] The disparity in outcomes between patients with Medicaid versus other insurance persists even after adjustment for disease severity and baseline comorbidities. Insurance type may influence the delivery of inpatient care through variation in access to invasive procedures and adherence to guideline‐concordant medical therapies.[9, 10, 11, 12] Medicaid patients may be more likely than uninsured patients to remain hospitalized pending postacute care placement rather than be discharged home with family support.[16] Medicaid patients are also less likely to leave against medical advice than uninsured patients.[17]

Currently, little is known about the impact of state Medicaid expansion status on length of stay (LOS) or mortality nationally. It is possible that hospitals in Medicaid‐expansion states have experienced relative worsening in LOS and mortality as their share of Medicaid patients has grown. Determining the impact of ACA implementation on payer mix and patient outcomes is particularly important for academic medical centers (AMCs), as they traditionally care for the greatest percentage of both Medicaid and uninsured patients.[18] We sought to characterize the impact of state Medicaid expansion status on payer mix, LOS, and in‐hospital mortality for general medicine patients at AMCs in the United States.

METHODS

The University HealthSystem Consortium (UHC) is an alliance of 117 AMCs and 310 affiliated hospitals, representing >90% of such institutions in the US. We queried the online UHC Clinical Data Base/Resource Manager (CDB/RM) to obtain hospital‐level insurance, LOS, and mortality data for inpatients discharged from a general medicine service between October 1, 2012 and September 30, 2015. We excluded hospitals that were missing data for any month within the study period. No patient‐level data were accessed.

Our outcomes of interest were the proportion of discharges by primary payer (Medicare, commercial, Medicaid, uninsured, or other [eg, Tri‐Care or Workers' Compensation]), as well as the LOS index and mortality index. Both indices were defined as the ratio of the observed to expected values. To determine the expected LOS and mortality, the UHC 2015 risk adjustment models were applied to all cases, adjusting for variables such as patient demographics, low socioeconomic status, admit source and status, severity of illness, and comorbid conditions, as described by International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision codes. These models have been validated and are used for research and quality benchmarking for member institutions.[19]

We next stratified hospitals according to state Medicaid expansion status. We defined Medicaid‐expansion states as those that had expanded Medicaid by the end of the study period: Arizona, Arkansas, California, Colorado, Connecticut, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kentucky, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, Nevada, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, Ohio, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, Washington, Washington DC, and West Virginia. Nonexpansion states included Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Kansas, Louisiana, Missouri, Nebraska, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, Utah, Virginia, and Wisconsin. We excluded 12 states due to incomplete data: Alaska, Delaware, Hawaii, Idaho, North Dakota, Maine, Mississippi, Montana, Oklahoma, South Dakota, Vermont, and Wyoming.

We then identified our pre‐ and post‐ACA implementation periods. Medicaid coverage expansion took effect in all expansion states on January 1, 2014, with the exception of Michigan (April 1, 2014), New Hampshire (August 15, 2014), Pennsylvania (January 1, 2015), and Indiana (February 1, 2015).[3] We therefore defined October 1, 2012 to December 31, 2013 as the pre‐ACA implementation period and January 1, 2014 to September 30, 2015 as the post‐ACA implementation period for all states except for Michigan, New Hampshire, Pennsylvania, and Indiana. For these 4 states, we customized the pre‐ and post‐ACA implementation periods to their respective dates of Medicaid expansion; for New Hampshire, we designated October 1, 2012 to July 31, 2014 as the pre‐ACA implementation period and September 1, 2014 to September 30, 2015 as the post‐ACA implementation period, as we were unable to distinguish before versus after data in August 2014 based on the midmonth expansion of Medicaid.

After stratifying hospitals into groups based on whether they were located in Medicaid‐expansion or nonexpansion states, the proportion of discharges by payer was compared between pre‐ and post‐ACA implementation periods both graphically by quarter and using linear regression models weighted for the number of cases from each hospital. Next, for both Medicaid‐expansion and nonexpansion hospitals, LOS index and mortality index were compared before and after ACA implementation using linear regression models weighted for the number of cases from each hospital, both overall and by payer. Difference‐in‐differences estimations were then completed to compare the proportion of discharges by payer, LOS index, and mortality index between Medicaid‐expansion and nonexpansion hospitals before and after ACA implementation. Post hoc linear regression analyses were completed to evaluate the effect of clustering by state level strata on payer mix and LOS and mortality indices. A 2‐sided P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Data analyses were performed using Stata 12.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

RESULTS

We identified 4,258,952 discharges among general medicine patients from 211 hospitals in 38 states and Washington, DC between October 1, 2012, and September 30, 2015. This included 3,144,488 discharges from 156 hospitals in 24 Medicaid‐expansion states and Washington, DC and 1,114,464 discharges from 55 hospitals in 14 nonexpansion states.

Figure 1 shows the trends in payer mix over time for hospitals in both Medicaid‐expansion and nonexpansion states. As summarized in Table 1, hospitals in Medicaid‐expansion states experienced a significant 3.7‐percentage point increase in Medicaid discharges (P = 0.013) and 2.9‐percentage point decrease in uninsured discharges (P < 0.001) after ACA implementation. This represented an approximately 19% jump and 60% drop in Medicaid and uninsured discharges, respectively. Hospitals in nonexpansion states saw no significant change in the proportion of discharges by payer after ACA implementation. In the difference‐in‐differences analysis, there was a trend toward a greater change in the proportion of Medicaid discharges pre‐ to post‐ACA implementation among hospitals in Medicaid‐expansion states compared to hospitals in nonexpansion states (mean difference‐in‐differences 4.1%, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.3%, 8.6%, P = 0.070).

| Medicaid‐expansion n=156 hospitals; 3,144,488 cases | Non‐expansion n=55 hospitals; 1,114,464 cases | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre‐ACA Implementation (1,453,090 Cases) | Post‐ACA Implementation (1,691,398 Cases) | Mean Difference | P Value | Pre‐ACA Implementation (455,440 Cases) | Post‐ACA Implementation (659,024 Cases) | Mean Difference | P Value | Mean Difference‐in‐Differences | P Value | |

| ||||||||||

| Payer mix, % (95% CI) | ||||||||||

| Medicare | 48.6 (46.2, 51.0)* | 48.3 (45.9, 50.7) | 0.3 (3.6, 3.1) | 0.865 | 44.3 (40.7, 47.7)* | 45.3 (41.9, 48.6) | 1.0 (3.8, 5.8) | 0.671 | 1.3 (7.1, 4.5) | 0.655 |

| Commercial | 23.1 (21.4, 24.7) | 23.2 (21.8, 24.6) | 0.2 (2.0, 2.3) | 0.882 | 21.5 (18.5, 24.6) | 22.7 (19.7, 25.8) | 1.2 (3.0, 5.4) | 0.574 | 1.0 (5.7, 3.6) | 0.662 |

| Medicaid | 19.6 (17.6, 21.6) | 23.3 (21.2, 25.5) | 3.7 (0.8, 6.6) | 0.013 | 19.4 (16.9, 21.9) | 19.0 (16.5, 21.4) | 0.4 (3.8, 3.0) | 0.812 | 4.1 (0.3, 8.6) | 0.070 |

| Uninsured | 5.0 (4.0, 5.9) | 2.0 (1.7, 2.3) | 2.9 (3.9, 2.0) | <0.001 | 10.9 (8.1, 13.7) | 9.4 (7.0, 11.7) | 1.5 (5.1, 2.1) | 0.407 | 1.4 (5.1, 2.2) | 0.442 |

| Other | 3.8 (2.6, 4.9) | 3.1 (2.0, 4.3) | 0.7 (2.3, 1.0) | 0.435 | 4.0 (2.9, 5.0) | 3.7 (2.6, 4.7) | 0.3 (1.7, 1.1) | 0.662 | 0.3 (2.5, 1.8) | 0.762 |

| LOS index, mean (95% CI) | ||||||||||

| Overall | 1.017 (0.996, 1.038) | 1.006 (0.981, 1.031) | 0.011 (0.044, 0.021) | 0.488 | 1.008 (0.974, 1.042) | 0.995 (0.961, 1.029) | 0.013 (0.061, 0.034) | 0.574 | 0.002 (0.055, 0.059) | 0.943 |

| Medicare | 1.012 (0.989, 1.035) | 0.999 (0.971, 1.027) | 0.013 (0.049, 0.023) | 0.488 | 0.982 (0.946, 1.017) | 0.979 (0.944, 1.013) | 0.003 (0.052, 0.046) | 0.899 | 0.010 (0.070, 0.051) | 0.754 |

| Commercial | 0.993 (0.974, 1.012) | 0.977 (0.955, 0.998) | 0.016 (0.045, 0.013) | 0.271 | 1.009 (0.978, 1.039) | 0.986 (0.956, 1.016) | 0.022 (0.065, 0.020) | 0.298 | 0.006 (0.044, 0.057) | 0.809 |

| Medicaid | 1.059 (1.036, 1.082) | 1.043 (1.018, 1.067) | 0.016 (0.049, 0.017) | 0.349 | 1.064 (1.020, 1.108) | 1.060 (1.015, 1.106) | 0.004 (0.066, 0.059) | 0.911 | 0.012 (0.082, 0.057) | 0.727 |

| Uninsured | 0.960 (0.933, 0.988) | 0.925 (0.890, 0.961) | 0.035 (0.080, 0.010) | 0.126 | 0.972 (0.935, 1.009) | 0.944 (0.909, 0.979) | 0.028 (0.078, 0.022) | 0.273 | 0.007 (0.074, 0.060) | 0.835 |

| Other | 0.988 (0.960, 1.017) | 0.984 (0.952, 1.015) | 0.005 (0.047, 0.037) | 0.822 | 1.022 (0.973, 1.071) | 0.984 (0.944, 1.024) | 0.038 (0.100, 0.024) | 0.232 | 0.033 (0.042, 0.107) | 0.386 |

| Mortality index, mean (95% CI) | ||||||||||

| Overall | 1.000 (0.955, 1.045) | 0.878 (0.836, 0.921) | 0.122 (0.183, 0.061) | <0.001 | 0.997 (0.931, 1.062) | 0.850 (0.800, 0.900) | 0.147 (0.227, 0.066) | 0.001 | 0.025 (0.076, 0.125) | 0.628 |

| Medicare | 0.990 (0.942, 1.038) | 0.871 (0.826, 0.917) | 0.119 (0.185, 0.053) | <0.001 | 1.000 (0.925, 1.076) | 0.844 (0.788, 0.900) | 0.156 (0.249, 0.064) | 0.001 | 0.038 (0.075, 0.150) | 0.513 |

| Commercial | 1.045 (0.934, 1.155) | 0.908 (0.842, 0.975) | 0.136 (0.264, 0.008) | 0.037 | 1.023 (0.935, 1.111) | 0.820 (0.758, 0.883) | 0.203 (0.309, 0.096) | <0.001 | 0.067 (0.099, 0.232) | 0.430 |

| Medicaid | 0.894 (0.845, 0.942) | 0.786 (0.748, 0.824) | 0.107 (0.168, 0.046) | 0.001 | 0.937 (0.861, 1.013) | 0.789 (0.733, 0.844) | 0.148 (0.242, 0.055) | 0.002 | 0.041 (0.069, 0.151) | 0.464 |

| Uninsured | 1.172 (1.007, 1.337)∥ | 1.136 (0.968, 1.303) | 0.037 (0.271, 0.197) | 0.758 | 0.868 (0.768, 0.968)∥ | 0.850 (0.761, 0.939) | 0.017 (0.149, 0.115) | 0.795 | 0.019 (0.287, 0.248) | 0.887 |

| Other | 1.376 (1.052, 1.700)# | 1.156 (0.910, 1.402) | 0.220 (0.624, 0.184) | 0.285 | 1.009 (0.868, 1.150) # | 0.874 (0.682, 1.066) | 0.135 (0.369, 0.099) | 0.254 | 0.085 (0.555, 0.380) | 0.720 |

Table 1 shows that the overall LOS index remained unchanged pre‐ to post‐ACA implementation for both Medicaid‐expansion (1.017 to 1.006, P = 0.488) and nonexpansion hospitals (1.008 to 0.995, P = 0.574). LOS indices for each payer type also remained unchanged. The overall mortality index significantly improved pre‐ to post‐ACA implementation for both Medicaid‐expansion (1.000 to 0.878, P < 0.001) and nonexpansion hospitals (0.997 to 0.850, P = 0.001). Among both Medicaid‐expansion and nonexpansion hospitals, the mortality index significantly improved for Medicare, commercial, and Medicaid discharges but not for uninsured or other discharges. In the difference‐in‐differences analysis, the changes in LOS indices and mortality indices pre‐ to post‐ACA implementation did not differ significantly between hospitals in Medicaid‐expansion versus nonexpansion states.

In post hoc linear regression analyses of payer mix and LOS and mortality indices clustered by state‐level strata, point estimates were minimally changed. Although 95% CIs were slightly wider, statistical significance was unchanged from our primary analyses (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

We found that ACA implementation had a significant impact on payer mix for general medicine patients at AMCs in the United States, primarily by increasing the number of Medicaid beneficiaries and by decreasing the number of uninsured patients in Medicaid‐expansion states. State Medicaid expansion status did not appear to influence either LOS or in‐hospital mortality.

Our study offers some of the longest‐term data currently available on the impact of ACA implementation on payer mix trends and encompasses more states than others have previously. Although we uniquely focused on general medicine patients at AMCs, our results are similar to those seen for US hospitals overall. Nikpay and colleagues evaluated payer mix trends for non‐Medicare adult inpatient stays in 16 states through the second quarter of 2014 using the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project database through the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.[4] They found a relative 20% increase and 50% decrease in Medicaid and uninsured discharges in Medicaid‐expansion states, along with nonsignificant changes in nonexpansion states. Hempstead and Cantor assessed payer mix for non‐Medicare discharges using state hospital association data from 21 states through the fourth quarter of 2014 and found a significant increase in Medicaid patients as well as a nearly significant decrease in uninsured patients in expansion states relative to nonexpansion states.[5] The Department of Health and Human Services also reported that uninsured/self‐pay discharges fell substantially (65%73%) in Medicaid‐expansion states by the end of 2014, with slight decreases in nonexpansion states.[20]

In contrast to our hypothesis, the overall LOS and in‐hospital mortality indices were not influenced by state Medicaid expansion status. From a purely mathematical standpoint, the contribution of Medicaid patients to the overall LOS and mortality indices may have been eclipsed by Medicare and commercially insured patients, who represented a higher proportion of total discharges. The lack of impact of state Medicaid expansion status on overall LOS and mortality indices did not appear to occur as a result of indices for Medicaid patients trending toward the mean. As predicted based on observational studies, Medicaid patients in our study tended to have a higher LOS index than those with other insurance types. Medicaid patients actually tended to have a lower mortality index in our analysis; the reason for this latter finding is unclear and in contrast to other published studies.[6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 21]

To our knowledge, no other studies have evaluated the effect of payer mix changes under the ACA on inpatient outcomes. However, new evidence is emerging on outpatient outcomes. Low‐income adults in Medicaid‐expansion states have reported greater gains in access to primary care services and in the diagnosis of certain chronic health conditions than those in nonexpansion states as a result of ACA implementation.[22, 23] Such improvements in the outpatient setting might be expected to reduce patient acuity on admission. However, they would not necessarily translate to relative improvements in LOS or mortality indices for Medicaid‐expansion hospitals, as the UHC risk adjustment models controlled for disease severity on admission.

Similarly, few studies have assessed the impact of payer mix changes under previous state Medicaid expansions on inpatient outcomes. After Massachusetts expanded Medicaid and enacted near‐universal healthcare coverage in 2006, a minimal LOS reduction of just 0.05 days was observed.[24] New York expanded Medicaid eligibility to nondisabled childless adults with incomes below 100% of the federal poverty level in September 2001, whereas Arizona did so in November 2001 and Maine in October 2002. A study comparing outcomes in these states to 4 neighboring nonexpansion states found a relative reduction in annual all‐cause mortality of 6.1% population wide; however, it did not assess in‐hospital mortality.[25] The Oregon Health Insurance Experiment that randomized low‐income adults to expanded Medicaid coverage or not in 2008 has also reported on outpatient rather than inpatient outcomes.[26]

Our findings have potential implications for health policymakers. That Medicaid expansion status had a neutral effect on both LOS and mortality indices in our analysis should be reassuring for states contemplating Medicaid expansion in the future. Our results also highlight the need for further efforts to reduce disparities in inpatient care based on payer status. For example, although Medicare, commercially insured, and Medicaid patients witnessed significant improvements in mortality indices pre‐ to post‐ACA implementation in hospitals in both Medicaid‐expansion and nonexpansion states, uninsured patients did not.

This study has several limitations. First, our analysis of the impact of ACA implementation on payer mix did not account for concurrent socioeconomic trends that may have influenced insurance coverage across the United States. However, the main goal of this analysis was to demonstrate that changes in payer mix did in fact occur over time, to provide rationale for our subsequent LOS and mortality analyses. Second, we could not control for variation in the design and implementation of Medicaid expansions across states as permitted under the federal Section 1115 waiver process. Third, we only had access to hospital‐level data through the UHC CDB/RM, rather than individual patient data. We attempted to mitigate this limitation by weighting data according to the number of cases per hospital. Lastly, additional patient‐level factors that may influence LOS or mortality may not be included in the UHC risk adjustment models.

In summary, the differential shift in payer mix between Medicaid‐expansion and nonexpansion states did not influence overall LOS or in‐hospital mortality for general medicine patients at AMCs in the United States. Additional research could help to determine the impact of ACA implementation on other patient outcomes that may be dependent on insurance status, such as readmissions or hospital‐acquired complications.

Disclosures: M.E.A. conceived of the study concept and design, assisted with data acquisition, and drafted the manuscript. J.J.G. assisted with study design and made critical revisions to the manuscript. D.A. assisted with study design and made critical revisions to the manuscript. R.P. assisted with study design and made critical revisions to the manuscript. M.L. assisted with study design and data acquisition and made critical revisions to the manuscript. C.D.J. assisted with study design, performed data analyses, and made critical revisions to the manuscript. A modified abstract was presented in poster format at the University HealthSystem Consortium Annual Conference held September 30 to October 2, 2015 in Orlando, Florida, as well as at the Society of Hospital Medicine Research, Innovations, and Vignettes 2016 Annual Meeting held March 69, 2016, in San Diego, California. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

On January 1, 2014, several major provisions of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) took effect, including introduction of the individual mandate for health insurance coverage, opening of the Health Insurance Marketplace, and expansion of Medicaid eligibility to Americans earning up to 133% of the federal poverty level.[1] Nearly 9 million US adults have enrolled in Medicaid since that time, primarily in the 31 states and Washington, DC that have opted into Medicaid expansion.[2, 3] ACA implementation has also had a significant impact on hospital payer mix, primarily by reducing the volume of uncompensated care in Medicaid‐expansion states.[4, 5]

The differential shift in payer mix in Medicaid‐expansion versus nonexpansion states may be relevant to hospitals beyond reimbursement. Medicaid insurance has historically been associated with longer hospitalizations and higher in‐hospital mortality in diverse patient populations, more so than commercial insurance and often even uninsured payer status.[6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15] The disparity in outcomes between patients with Medicaid versus other insurance persists even after adjustment for disease severity and baseline comorbidities. Insurance type may influence the delivery of inpatient care through variation in access to invasive procedures and adherence to guideline‐concordant medical therapies.[9, 10, 11, 12] Medicaid patients may be more likely than uninsured patients to remain hospitalized pending postacute care placement rather than be discharged home with family support.[16] Medicaid patients are also less likely to leave against medical advice than uninsured patients.[17]

Currently, little is known about the impact of state Medicaid expansion status on length of stay (LOS) or mortality nationally. It is possible that hospitals in Medicaid‐expansion states have experienced relative worsening in LOS and mortality as their share of Medicaid patients has grown. Determining the impact of ACA implementation on payer mix and patient outcomes is particularly important for academic medical centers (AMCs), as they traditionally care for the greatest percentage of both Medicaid and uninsured patients.[18] We sought to characterize the impact of state Medicaid expansion status on payer mix, LOS, and in‐hospital mortality for general medicine patients at AMCs in the United States.

METHODS

The University HealthSystem Consortium (UHC) is an alliance of 117 AMCs and 310 affiliated hospitals, representing >90% of such institutions in the US. We queried the online UHC Clinical Data Base/Resource Manager (CDB/RM) to obtain hospital‐level insurance, LOS, and mortality data for inpatients discharged from a general medicine service between October 1, 2012 and September 30, 2015. We excluded hospitals that were missing data for any month within the study period. No patient‐level data were accessed.

Our outcomes of interest were the proportion of discharges by primary payer (Medicare, commercial, Medicaid, uninsured, or other [eg, Tri‐Care or Workers' Compensation]), as well as the LOS index and mortality index. Both indices were defined as the ratio of the observed to expected values. To determine the expected LOS and mortality, the UHC 2015 risk adjustment models were applied to all cases, adjusting for variables such as patient demographics, low socioeconomic status, admit source and status, severity of illness, and comorbid conditions, as described by International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision codes. These models have been validated and are used for research and quality benchmarking for member institutions.[19]

We next stratified hospitals according to state Medicaid expansion status. We defined Medicaid‐expansion states as those that had expanded Medicaid by the end of the study period: Arizona, Arkansas, California, Colorado, Connecticut, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kentucky, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, Nevada, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, Ohio, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, Washington, Washington DC, and West Virginia. Nonexpansion states included Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Kansas, Louisiana, Missouri, Nebraska, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, Utah, Virginia, and Wisconsin. We excluded 12 states due to incomplete data: Alaska, Delaware, Hawaii, Idaho, North Dakota, Maine, Mississippi, Montana, Oklahoma, South Dakota, Vermont, and Wyoming.

We then identified our pre‐ and post‐ACA implementation periods. Medicaid coverage expansion took effect in all expansion states on January 1, 2014, with the exception of Michigan (April 1, 2014), New Hampshire (August 15, 2014), Pennsylvania (January 1, 2015), and Indiana (February 1, 2015).[3] We therefore defined October 1, 2012 to December 31, 2013 as the pre‐ACA implementation period and January 1, 2014 to September 30, 2015 as the post‐ACA implementation period for all states except for Michigan, New Hampshire, Pennsylvania, and Indiana. For these 4 states, we customized the pre‐ and post‐ACA implementation periods to their respective dates of Medicaid expansion; for New Hampshire, we designated October 1, 2012 to July 31, 2014 as the pre‐ACA implementation period and September 1, 2014 to September 30, 2015 as the post‐ACA implementation period, as we were unable to distinguish before versus after data in August 2014 based on the midmonth expansion of Medicaid.

After stratifying hospitals into groups based on whether they were located in Medicaid‐expansion or nonexpansion states, the proportion of discharges by payer was compared between pre‐ and post‐ACA implementation periods both graphically by quarter and using linear regression models weighted for the number of cases from each hospital. Next, for both Medicaid‐expansion and nonexpansion hospitals, LOS index and mortality index were compared before and after ACA implementation using linear regression models weighted for the number of cases from each hospital, both overall and by payer. Difference‐in‐differences estimations were then completed to compare the proportion of discharges by payer, LOS index, and mortality index between Medicaid‐expansion and nonexpansion hospitals before and after ACA implementation. Post hoc linear regression analyses were completed to evaluate the effect of clustering by state level strata on payer mix and LOS and mortality indices. A 2‐sided P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Data analyses were performed using Stata 12.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

RESULTS

We identified 4,258,952 discharges among general medicine patients from 211 hospitals in 38 states and Washington, DC between October 1, 2012, and September 30, 2015. This included 3,144,488 discharges from 156 hospitals in 24 Medicaid‐expansion states and Washington, DC and 1,114,464 discharges from 55 hospitals in 14 nonexpansion states.

Figure 1 shows the trends in payer mix over time for hospitals in both Medicaid‐expansion and nonexpansion states. As summarized in Table 1, hospitals in Medicaid‐expansion states experienced a significant 3.7‐percentage point increase in Medicaid discharges (P = 0.013) and 2.9‐percentage point decrease in uninsured discharges (P < 0.001) after ACA implementation. This represented an approximately 19% jump and 60% drop in Medicaid and uninsured discharges, respectively. Hospitals in nonexpansion states saw no significant change in the proportion of discharges by payer after ACA implementation. In the difference‐in‐differences analysis, there was a trend toward a greater change in the proportion of Medicaid discharges pre‐ to post‐ACA implementation among hospitals in Medicaid‐expansion states compared to hospitals in nonexpansion states (mean difference‐in‐differences 4.1%, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.3%, 8.6%, P = 0.070).

| Medicaid‐expansion n=156 hospitals; 3,144,488 cases | Non‐expansion n=55 hospitals; 1,114,464 cases | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre‐ACA Implementation (1,453,090 Cases) | Post‐ACA Implementation (1,691,398 Cases) | Mean Difference | P Value | Pre‐ACA Implementation (455,440 Cases) | Post‐ACA Implementation (659,024 Cases) | Mean Difference | P Value | Mean Difference‐in‐Differences | P Value | |

| ||||||||||

| Payer mix, % (95% CI) | ||||||||||

| Medicare | 48.6 (46.2, 51.0)* | 48.3 (45.9, 50.7) | 0.3 (3.6, 3.1) | 0.865 | 44.3 (40.7, 47.7)* | 45.3 (41.9, 48.6) | 1.0 (3.8, 5.8) | 0.671 | 1.3 (7.1, 4.5) | 0.655 |

| Commercial | 23.1 (21.4, 24.7) | 23.2 (21.8, 24.6) | 0.2 (2.0, 2.3) | 0.882 | 21.5 (18.5, 24.6) | 22.7 (19.7, 25.8) | 1.2 (3.0, 5.4) | 0.574 | 1.0 (5.7, 3.6) | 0.662 |

| Medicaid | 19.6 (17.6, 21.6) | 23.3 (21.2, 25.5) | 3.7 (0.8, 6.6) | 0.013 | 19.4 (16.9, 21.9) | 19.0 (16.5, 21.4) | 0.4 (3.8, 3.0) | 0.812 | 4.1 (0.3, 8.6) | 0.070 |

| Uninsured | 5.0 (4.0, 5.9) | 2.0 (1.7, 2.3) | 2.9 (3.9, 2.0) | <0.001 | 10.9 (8.1, 13.7) | 9.4 (7.0, 11.7) | 1.5 (5.1, 2.1) | 0.407 | 1.4 (5.1, 2.2) | 0.442 |

| Other | 3.8 (2.6, 4.9) | 3.1 (2.0, 4.3) | 0.7 (2.3, 1.0) | 0.435 | 4.0 (2.9, 5.0) | 3.7 (2.6, 4.7) | 0.3 (1.7, 1.1) | 0.662 | 0.3 (2.5, 1.8) | 0.762 |

| LOS index, mean (95% CI) | ||||||||||

| Overall | 1.017 (0.996, 1.038) | 1.006 (0.981, 1.031) | 0.011 (0.044, 0.021) | 0.488 | 1.008 (0.974, 1.042) | 0.995 (0.961, 1.029) | 0.013 (0.061, 0.034) | 0.574 | 0.002 (0.055, 0.059) | 0.943 |

| Medicare | 1.012 (0.989, 1.035) | 0.999 (0.971, 1.027) | 0.013 (0.049, 0.023) | 0.488 | 0.982 (0.946, 1.017) | 0.979 (0.944, 1.013) | 0.003 (0.052, 0.046) | 0.899 | 0.010 (0.070, 0.051) | 0.754 |

| Commercial | 0.993 (0.974, 1.012) | 0.977 (0.955, 0.998) | 0.016 (0.045, 0.013) | 0.271 | 1.009 (0.978, 1.039) | 0.986 (0.956, 1.016) | 0.022 (0.065, 0.020) | 0.298 | 0.006 (0.044, 0.057) | 0.809 |

| Medicaid | 1.059 (1.036, 1.082) | 1.043 (1.018, 1.067) | 0.016 (0.049, 0.017) | 0.349 | 1.064 (1.020, 1.108) | 1.060 (1.015, 1.106) | 0.004 (0.066, 0.059) | 0.911 | 0.012 (0.082, 0.057) | 0.727 |

| Uninsured | 0.960 (0.933, 0.988) | 0.925 (0.890, 0.961) | 0.035 (0.080, 0.010) | 0.126 | 0.972 (0.935, 1.009) | 0.944 (0.909, 0.979) | 0.028 (0.078, 0.022) | 0.273 | 0.007 (0.074, 0.060) | 0.835 |

| Other | 0.988 (0.960, 1.017) | 0.984 (0.952, 1.015) | 0.005 (0.047, 0.037) | 0.822 | 1.022 (0.973, 1.071) | 0.984 (0.944, 1.024) | 0.038 (0.100, 0.024) | 0.232 | 0.033 (0.042, 0.107) | 0.386 |

| Mortality index, mean (95% CI) | ||||||||||

| Overall | 1.000 (0.955, 1.045) | 0.878 (0.836, 0.921) | 0.122 (0.183, 0.061) | <0.001 | 0.997 (0.931, 1.062) | 0.850 (0.800, 0.900) | 0.147 (0.227, 0.066) | 0.001 | 0.025 (0.076, 0.125) | 0.628 |

| Medicare | 0.990 (0.942, 1.038) | 0.871 (0.826, 0.917) | 0.119 (0.185, 0.053) | <0.001 | 1.000 (0.925, 1.076) | 0.844 (0.788, 0.900) | 0.156 (0.249, 0.064) | 0.001 | 0.038 (0.075, 0.150) | 0.513 |

| Commercial | 1.045 (0.934, 1.155) | 0.908 (0.842, 0.975) | 0.136 (0.264, 0.008) | 0.037 | 1.023 (0.935, 1.111) | 0.820 (0.758, 0.883) | 0.203 (0.309, 0.096) | <0.001 | 0.067 (0.099, 0.232) | 0.430 |

| Medicaid | 0.894 (0.845, 0.942) | 0.786 (0.748, 0.824) | 0.107 (0.168, 0.046) | 0.001 | 0.937 (0.861, 1.013) | 0.789 (0.733, 0.844) | 0.148 (0.242, 0.055) | 0.002 | 0.041 (0.069, 0.151) | 0.464 |

| Uninsured | 1.172 (1.007, 1.337)∥ | 1.136 (0.968, 1.303) | 0.037 (0.271, 0.197) | 0.758 | 0.868 (0.768, 0.968)∥ | 0.850 (0.761, 0.939) | 0.017 (0.149, 0.115) | 0.795 | 0.019 (0.287, 0.248) | 0.887 |

| Other | 1.376 (1.052, 1.700)# | 1.156 (0.910, 1.402) | 0.220 (0.624, 0.184) | 0.285 | 1.009 (0.868, 1.150) # | 0.874 (0.682, 1.066) | 0.135 (0.369, 0.099) | 0.254 | 0.085 (0.555, 0.380) | 0.720 |

Table 1 shows that the overall LOS index remained unchanged pre‐ to post‐ACA implementation for both Medicaid‐expansion (1.017 to 1.006, P = 0.488) and nonexpansion hospitals (1.008 to 0.995, P = 0.574). LOS indices for each payer type also remained unchanged. The overall mortality index significantly improved pre‐ to post‐ACA implementation for both Medicaid‐expansion (1.000 to 0.878, P < 0.001) and nonexpansion hospitals (0.997 to 0.850, P = 0.001). Among both Medicaid‐expansion and nonexpansion hospitals, the mortality index significantly improved for Medicare, commercial, and Medicaid discharges but not for uninsured or other discharges. In the difference‐in‐differences analysis, the changes in LOS indices and mortality indices pre‐ to post‐ACA implementation did not differ significantly between hospitals in Medicaid‐expansion versus nonexpansion states.

In post hoc linear regression analyses of payer mix and LOS and mortality indices clustered by state‐level strata, point estimates were minimally changed. Although 95% CIs were slightly wider, statistical significance was unchanged from our primary analyses (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

We found that ACA implementation had a significant impact on payer mix for general medicine patients at AMCs in the United States, primarily by increasing the number of Medicaid beneficiaries and by decreasing the number of uninsured patients in Medicaid‐expansion states. State Medicaid expansion status did not appear to influence either LOS or in‐hospital mortality.

Our study offers some of the longest‐term data currently available on the impact of ACA implementation on payer mix trends and encompasses more states than others have previously. Although we uniquely focused on general medicine patients at AMCs, our results are similar to those seen for US hospitals overall. Nikpay and colleagues evaluated payer mix trends for non‐Medicare adult inpatient stays in 16 states through the second quarter of 2014 using the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project database through the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.[4] They found a relative 20% increase and 50% decrease in Medicaid and uninsured discharges in Medicaid‐expansion states, along with nonsignificant changes in nonexpansion states. Hempstead and Cantor assessed payer mix for non‐Medicare discharges using state hospital association data from 21 states through the fourth quarter of 2014 and found a significant increase in Medicaid patients as well as a nearly significant decrease in uninsured patients in expansion states relative to nonexpansion states.[5] The Department of Health and Human Services also reported that uninsured/self‐pay discharges fell substantially (65%73%) in Medicaid‐expansion states by the end of 2014, with slight decreases in nonexpansion states.[20]

In contrast to our hypothesis, the overall LOS and in‐hospital mortality indices were not influenced by state Medicaid expansion status. From a purely mathematical standpoint, the contribution of Medicaid patients to the overall LOS and mortality indices may have been eclipsed by Medicare and commercially insured patients, who represented a higher proportion of total discharges. The lack of impact of state Medicaid expansion status on overall LOS and mortality indices did not appear to occur as a result of indices for Medicaid patients trending toward the mean. As predicted based on observational studies, Medicaid patients in our study tended to have a higher LOS index than those with other insurance types. Medicaid patients actually tended to have a lower mortality index in our analysis; the reason for this latter finding is unclear and in contrast to other published studies.[6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 21]

To our knowledge, no other studies have evaluated the effect of payer mix changes under the ACA on inpatient outcomes. However, new evidence is emerging on outpatient outcomes. Low‐income adults in Medicaid‐expansion states have reported greater gains in access to primary care services and in the diagnosis of certain chronic health conditions than those in nonexpansion states as a result of ACA implementation.[22, 23] Such improvements in the outpatient setting might be expected to reduce patient acuity on admission. However, they would not necessarily translate to relative improvements in LOS or mortality indices for Medicaid‐expansion hospitals, as the UHC risk adjustment models controlled for disease severity on admission.

Similarly, few studies have assessed the impact of payer mix changes under previous state Medicaid expansions on inpatient outcomes. After Massachusetts expanded Medicaid and enacted near‐universal healthcare coverage in 2006, a minimal LOS reduction of just 0.05 days was observed.[24] New York expanded Medicaid eligibility to nondisabled childless adults with incomes below 100% of the federal poverty level in September 2001, whereas Arizona did so in November 2001 and Maine in October 2002. A study comparing outcomes in these states to 4 neighboring nonexpansion states found a relative reduction in annual all‐cause mortality of 6.1% population wide; however, it did not assess in‐hospital mortality.[25] The Oregon Health Insurance Experiment that randomized low‐income adults to expanded Medicaid coverage or not in 2008 has also reported on outpatient rather than inpatient outcomes.[26]

Our findings have potential implications for health policymakers. That Medicaid expansion status had a neutral effect on both LOS and mortality indices in our analysis should be reassuring for states contemplating Medicaid expansion in the future. Our results also highlight the need for further efforts to reduce disparities in inpatient care based on payer status. For example, although Medicare, commercially insured, and Medicaid patients witnessed significant improvements in mortality indices pre‐ to post‐ACA implementation in hospitals in both Medicaid‐expansion and nonexpansion states, uninsured patients did not.

This study has several limitations. First, our analysis of the impact of ACA implementation on payer mix did not account for concurrent socioeconomic trends that may have influenced insurance coverage across the United States. However, the main goal of this analysis was to demonstrate that changes in payer mix did in fact occur over time, to provide rationale for our subsequent LOS and mortality analyses. Second, we could not control for variation in the design and implementation of Medicaid expansions across states as permitted under the federal Section 1115 waiver process. Third, we only had access to hospital‐level data through the UHC CDB/RM, rather than individual patient data. We attempted to mitigate this limitation by weighting data according to the number of cases per hospital. Lastly, additional patient‐level factors that may influence LOS or mortality may not be included in the UHC risk adjustment models.

In summary, the differential shift in payer mix between Medicaid‐expansion and nonexpansion states did not influence overall LOS or in‐hospital mortality for general medicine patients at AMCs in the United States. Additional research could help to determine the impact of ACA implementation on other patient outcomes that may be dependent on insurance status, such as readmissions or hospital‐acquired complications.

Disclosures: M.E.A. conceived of the study concept and design, assisted with data acquisition, and drafted the manuscript. J.J.G. assisted with study design and made critical revisions to the manuscript. D.A. assisted with study design and made critical revisions to the manuscript. R.P. assisted with study design and made critical revisions to the manuscript. M.L. assisted with study design and data acquisition and made critical revisions to the manuscript. C.D.J. assisted with study design, performed data analyses, and made critical revisions to the manuscript. A modified abstract was presented in poster format at the University HealthSystem Consortium Annual Conference held September 30 to October 2, 2015 in Orlando, Florida, as well as at the Society of Hospital Medicine Research, Innovations, and Vignettes 2016 Annual Meeting held March 69, 2016, in San Diego, California. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

- Department of Health and Human Services. Key features of the Affordable Care Act by year. Available at: http://www.hhs.gov/healthcare/facts‐and‐features/key‐features‐of‐aca‐by‐year/index.html#2014. Accessed April 4, 2016.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicaid enrollment data collected through MBES. Available at: https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid‐chip‐program‐information/program‐information/medicaid‐and‐chip‐enrollment‐data/medicaid‐enrollment‐data‐collected‐through‐mbes.html. Accessed April 4, 2016.

- The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. Status of state action on the Medicaid expansion decision. Available at: http://kff.org/health‐reform/state‐indicator/state‐activity‐around‐expanding‐medicaid‐under‐the‐affordable‐care‐act. Accessed April 4, 2016.

- , , . Affordable Care Act Medicaid expansion reduced uninsured hospital stays in 2014. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35(1):106–110.

- , . State Medicaid expansion and changes in hospital volume according to payer. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(2):196–198.

- , , , , , . Understanding predictors of prolonged hospitalizations among general medicine patients: a guide and preliminary analysis. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(9):623–626.

- , , , . Impact of insurance and hospital ownership on hospital length of stay among patients with ambulatory care‐sensitive conditions. Ann Fam Med. 2011;9:489–495.

- , , . Insurance status and hospital care for myocardial infarction, stroke, and pneumonia. J Hosp Med. 2010;5:452–459.

- , , , , , . Payment source, quality of care, and outcomes in patients hospitalized with heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58(14):1465–1471.

- , , , , . The inpatient experience and predictors of length of stay for patients hospitalized with systolic heart failure: comparison by commercial, Medicaid, and Medicare payer type. J Med Econ. 2013;16(1):43–54.

- , , et al. Insurance coverage and care of patients with non‐ST‐segment elevation acute coronary syndromes. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145:739–748.

- , , , et al. Association of insurance status with inpatient treatment for coronary artery disease: findings from the Get with the Guidelines Program. Am Heart J. 2010;159:1026–1036.

- , , , et al. Primary payer status affects mortality for major surgical operations. Ann Surg. 2010;252:544–551.

- , , . Medicaid payer status is associated with in‐hospital morbidity and resource utilization following primary total joint arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96(21):e180.

- , , . The quality of care delivered to patients within the same hospital varies by insurance type. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32(10):1731–1739.

- , , , , . Effect of insurance status on postacute care among working age stroke survivors. Neurology. 2012;78(20):1590–1595.

- , , , . Hospitalizations in which patients leave the hospital against medical advice (AMA), 2007. HCUP statistical brief #78. August 2009. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2009. Available at: http://www.hcup‐us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb78.pdf. Accessed May 12, 2016.

- , , , . Characteristics of Medicaid and uninsured hospitalizations, 2012. HCUP statistical brief #182. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2014. Available at: http://www.hcup‐us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb182‐Medicaid‐Uninsured‐Hospitalizations‐2012.pdf. Accessed March 9, 2016.

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Mortality measurement: mortality risk adjustment methodology for University HealthSystem Consortium. Available at: http://archive.ahrq.gov/professionals/quality‐patient‐safety/quality‐resources/tools/mortality/Meurer.pdf. Accessed May 10, 2016.

- Department of Health and Human Services. Insurance expansion, hospital uncompensated care, and the Affordable Care Act. Available at: https://aspe.hhs.gov/pdf‐report/insurance‐expansion‐hospital‐uncompensated‐care‐and‐affordable‐care‐act. Accessed May 27, 2016.

- , , , . Our flawed but beneficial Medicaid program. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(16):e31.

- , , , . Changes in self‐reported insurance coverage, access to care, and health under the Affordable Care Act. JAMA. 2015;314(4):366–374.

- , . Early coverage, access, utilization, and health effects associated with the Affordable Care Act Medicaid Expansions: a quasi‐experimental study. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164(12):795–803.

- , . The impact of health care reform on hospital and preventive care: evidence from Massachusetts. J Public Econ. 2012;96(11–12):909–929.

- , , . Mortality and access to care among adults after state Medicaid expansions. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1025–1034.

- , , , et al. The Oregon Experiment—effects of Medicaid on clinical outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(18):1713–1722.

- Department of Health and Human Services. Key features of the Affordable Care Act by year. Available at: http://www.hhs.gov/healthcare/facts‐and‐features/key‐features‐of‐aca‐by‐year/index.html#2014. Accessed April 4, 2016.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicaid enrollment data collected through MBES. Available at: https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid‐chip‐program‐information/program‐information/medicaid‐and‐chip‐enrollment‐data/medicaid‐enrollment‐data‐collected‐through‐mbes.html. Accessed April 4, 2016.

- The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. Status of state action on the Medicaid expansion decision. Available at: http://kff.org/health‐reform/state‐indicator/state‐activity‐around‐expanding‐medicaid‐under‐the‐affordable‐care‐act. Accessed April 4, 2016.

- , , . Affordable Care Act Medicaid expansion reduced uninsured hospital stays in 2014. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35(1):106–110.

- , . State Medicaid expansion and changes in hospital volume according to payer. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(2):196–198.

- , , , , , . Understanding predictors of prolonged hospitalizations among general medicine patients: a guide and preliminary analysis. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(9):623–626.

- , , , . Impact of insurance and hospital ownership on hospital length of stay among patients with ambulatory care‐sensitive conditions. Ann Fam Med. 2011;9:489–495.

- , , . Insurance status and hospital care for myocardial infarction, stroke, and pneumonia. J Hosp Med. 2010;5:452–459.

- , , , , , . Payment source, quality of care, and outcomes in patients hospitalized with heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58(14):1465–1471.

- , , , , . The inpatient experience and predictors of length of stay for patients hospitalized with systolic heart failure: comparison by commercial, Medicaid, and Medicare payer type. J Med Econ. 2013;16(1):43–54.

- , , et al. Insurance coverage and care of patients with non‐ST‐segment elevation acute coronary syndromes. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145:739–748.

- , , , et al. Association of insurance status with inpatient treatment for coronary artery disease: findings from the Get with the Guidelines Program. Am Heart J. 2010;159:1026–1036.

- , , , et al. Primary payer status affects mortality for major surgical operations. Ann Surg. 2010;252:544–551.

- , , . Medicaid payer status is associated with in‐hospital morbidity and resource utilization following primary total joint arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96(21):e180.

- , , . The quality of care delivered to patients within the same hospital varies by insurance type. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32(10):1731–1739.

- , , , , . Effect of insurance status on postacute care among working age stroke survivors. Neurology. 2012;78(20):1590–1595.

- , , , . Hospitalizations in which patients leave the hospital against medical advice (AMA), 2007. HCUP statistical brief #78. August 2009. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2009. Available at: http://www.hcup‐us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb78.pdf. Accessed May 12, 2016.

- , , , . Characteristics of Medicaid and uninsured hospitalizations, 2012. HCUP statistical brief #182. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2014. Available at: http://www.hcup‐us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb182‐Medicaid‐Uninsured‐Hospitalizations‐2012.pdf. Accessed March 9, 2016.

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Mortality measurement: mortality risk adjustment methodology for University HealthSystem Consortium. Available at: http://archive.ahrq.gov/professionals/quality‐patient‐safety/quality‐resources/tools/mortality/Meurer.pdf. Accessed May 10, 2016.

- Department of Health and Human Services. Insurance expansion, hospital uncompensated care, and the Affordable Care Act. Available at: https://aspe.hhs.gov/pdf‐report/insurance‐expansion‐hospital‐uncompensated‐care‐and‐affordable‐care‐act. Accessed May 27, 2016.

- , , , . Our flawed but beneficial Medicaid program. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(16):e31.

- , , , . Changes in self‐reported insurance coverage, access to care, and health under the Affordable Care Act. JAMA. 2015;314(4):366–374.

- , . Early coverage, access, utilization, and health effects associated with the Affordable Care Act Medicaid Expansions: a quasi‐experimental study. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164(12):795–803.

- , . The impact of health care reform on hospital and preventive care: evidence from Massachusetts. J Public Econ. 2012;96(11–12):909–929.

- , , . Mortality and access to care among adults after state Medicaid expansions. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1025–1034.

- , , , et al. The Oregon Experiment—effects of Medicaid on clinical outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(18):1713–1722.