User login

Chlorpromazine (CPZ), a low-potency first-generation antipsychotic (FGA), was the first medication approved for the management of schizophrenia. Since its approval, some psychiatrists have prescribed subsequent antipsychotics based on CPZ’s efficacy and dosing. Comparing dosages of newer antipsychotics using a CPZ equivalent as a baseline remains a relevant method of determining which agent to prescribe, and at what dose.1,2

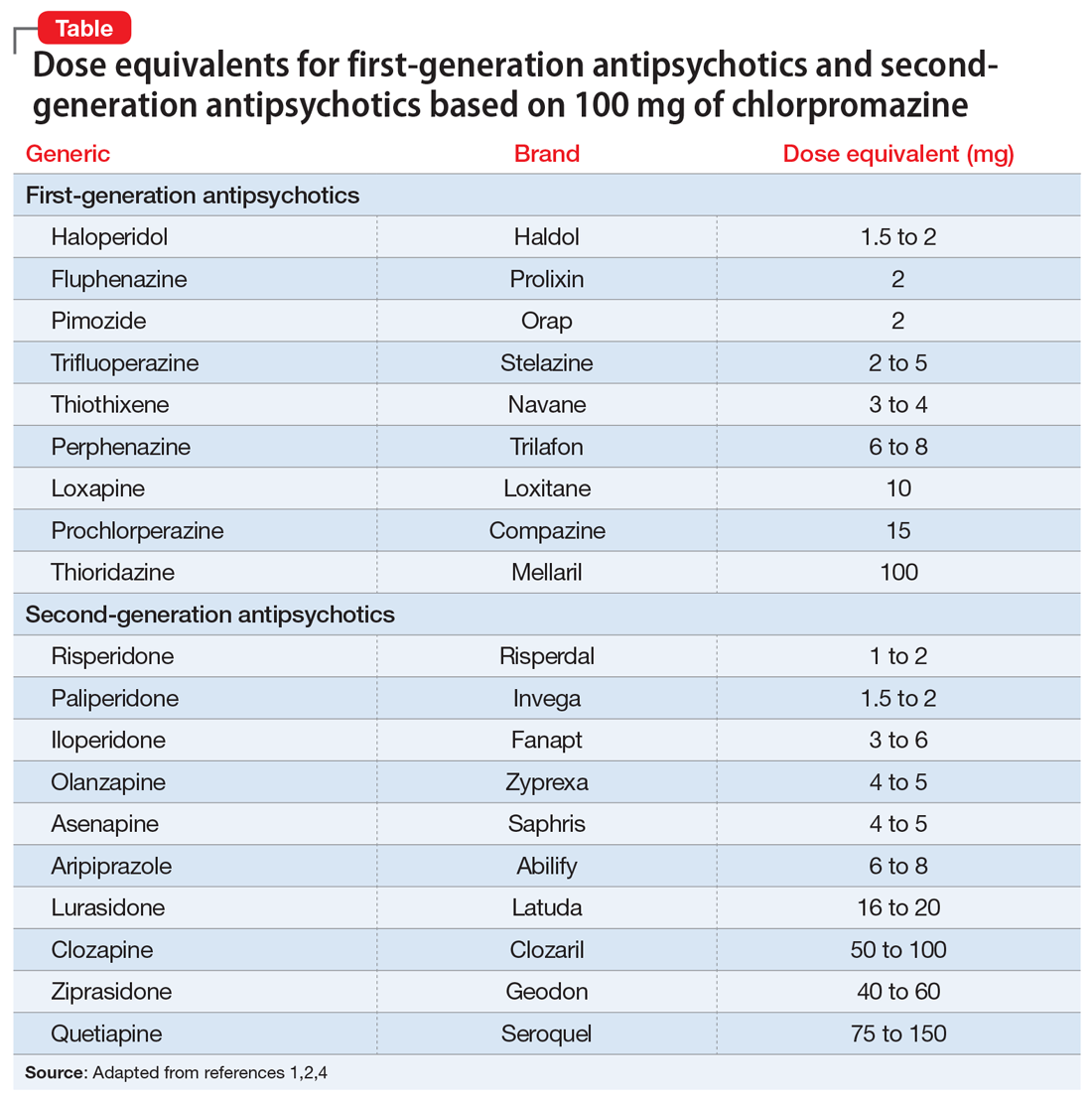

Psychiatrists frequently care for patients who are treatment-refractory or older adults with poor medication tolerance and age-related medical illness. Quick access to the comparative potency of different antipsychotics can help guide titration to the approximate equivalent dose of CPZ when initiating a medication, switching from 1 antipsychotic to another, or augmenting or combining antipsychotics. Fortunately, many authors, such as Woods2and Davis,3 have codified the dosing ratio equivalences of FGAs and second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs) using CPZ, 100 mg. To help psychiatrists use CPZ dosages as a point of comparison for prescribing other antipsychotics, the Table1,2,4 (page 14) lists dose equivalents for oral FGAs and SGAs based on CPZ, 100 mg. (For information on dose equivalents for injectable antipsychotics, see “Second-generation long-acting injectable antipsychotics: A practical guide,”

While this information cannot replace a psychiatrist’s clinical judgment, it can serve as a clinically useful prescribing tool. In addition to providing this Table, we discuss what you should consider when using these equivalents to switch antipsychotics and estimate the ultimate dose target for effective management of psychotic disorders.

A few caveats

Bioactive equivalent dosages should be targeted as a rough guide when switching from one FGA or SGA to another. Common indications for switching antipsychotics include an inadequate therapeutic response after a medication trial of an adequate dose and duration; relapse of psychosis despite medication adherence; intolerable adverse effects; cost; a new-onset, contraindicating medical illness; and lapses in medication compliance that necessitate a change to IM formulations.5 Keep in mind that medication changes should be tailored to the patient’s specific clinical characteristics.

Several other clinical and pharmacologic variabilities should be kept in mind when switching antipsychotics using CPZ dosage equivalents5,6:

- The therapeutic CPZ equivalent doses may be less precise for SGAs than for FGAs because the equivalents are largely based on dopaminergic blockade instead of cholinergic, serotonergic, or histaminergic systems

- For some antipsychotics, the relationship between dose and potency is nonlinear. For example, as the dosage of haloperidol increases, its relative antipsychotic potency decreases

- Differences in half-lives between 2 agents can add complexity to calculating the dosage equivalent

- Regardless of comparative dosing, before initiating a new antipsychotic, psychiatrists should read the dosing instructions in the FDA-approved package insert, and exercise caution before titrating a new medication to the maximum recommended dose.

1. Danivas V, Venkatasubramanian G. Current perspectives on chlorpromazine equivalents: comparing apples and oranges! Indian J Psychiatry. 2013;55(2):207-208.

2. Woods SW. Chlorpromazine equivalent doses for the newer atypical antipsychotics. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64(6):663-667.

3. Davis JM. Dose equivalence of the anti-psychotic drugs. J Psych Res. 1974;11:65-69.

4. Psychiatric pharmacy essentials: antipsychotic dose equivalents. College of Psychiatric and Neurologic Pharmacists. Accessed February 2, 2021. https://cpnp.org/guideline/essentials/antipsychotic-dose-equivalents

5. Guidelines for antipsychotic medication switches. Humber NHS. Last Reviewed September 2012. Accessed February 2, 2021. https://www.psychdb.com/_media/meds/antipsychotics/nhs_guidelines_antipsychotic_switch.pdf

6. Bobo WV. Switching antipsychotics: why, when, and how? Psychiatric Times. Published March 14, 2013. Accessed February 2, 2021. https://www.psychiatrictimes.com/view/switching-antipsychotics-why-when-and-how

Chlorpromazine (CPZ), a low-potency first-generation antipsychotic (FGA), was the first medication approved for the management of schizophrenia. Since its approval, some psychiatrists have prescribed subsequent antipsychotics based on CPZ’s efficacy and dosing. Comparing dosages of newer antipsychotics using a CPZ equivalent as a baseline remains a relevant method of determining which agent to prescribe, and at what dose.1,2

Psychiatrists frequently care for patients who are treatment-refractory or older adults with poor medication tolerance and age-related medical illness. Quick access to the comparative potency of different antipsychotics can help guide titration to the approximate equivalent dose of CPZ when initiating a medication, switching from 1 antipsychotic to another, or augmenting or combining antipsychotics. Fortunately, many authors, such as Woods2and Davis,3 have codified the dosing ratio equivalences of FGAs and second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs) using CPZ, 100 mg. To help psychiatrists use CPZ dosages as a point of comparison for prescribing other antipsychotics, the Table1,2,4 (page 14) lists dose equivalents for oral FGAs and SGAs based on CPZ, 100 mg. (For information on dose equivalents for injectable antipsychotics, see “Second-generation long-acting injectable antipsychotics: A practical guide,”

While this information cannot replace a psychiatrist’s clinical judgment, it can serve as a clinically useful prescribing tool. In addition to providing this Table, we discuss what you should consider when using these equivalents to switch antipsychotics and estimate the ultimate dose target for effective management of psychotic disorders.

A few caveats

Bioactive equivalent dosages should be targeted as a rough guide when switching from one FGA or SGA to another. Common indications for switching antipsychotics include an inadequate therapeutic response after a medication trial of an adequate dose and duration; relapse of psychosis despite medication adherence; intolerable adverse effects; cost; a new-onset, contraindicating medical illness; and lapses in medication compliance that necessitate a change to IM formulations.5 Keep in mind that medication changes should be tailored to the patient’s specific clinical characteristics.

Several other clinical and pharmacologic variabilities should be kept in mind when switching antipsychotics using CPZ dosage equivalents5,6:

- The therapeutic CPZ equivalent doses may be less precise for SGAs than for FGAs because the equivalents are largely based on dopaminergic blockade instead of cholinergic, serotonergic, or histaminergic systems

- For some antipsychotics, the relationship between dose and potency is nonlinear. For example, as the dosage of haloperidol increases, its relative antipsychotic potency decreases

- Differences in half-lives between 2 agents can add complexity to calculating the dosage equivalent

- Regardless of comparative dosing, before initiating a new antipsychotic, psychiatrists should read the dosing instructions in the FDA-approved package insert, and exercise caution before titrating a new medication to the maximum recommended dose.

Chlorpromazine (CPZ), a low-potency first-generation antipsychotic (FGA), was the first medication approved for the management of schizophrenia. Since its approval, some psychiatrists have prescribed subsequent antipsychotics based on CPZ’s efficacy and dosing. Comparing dosages of newer antipsychotics using a CPZ equivalent as a baseline remains a relevant method of determining which agent to prescribe, and at what dose.1,2

Psychiatrists frequently care for patients who are treatment-refractory or older adults with poor medication tolerance and age-related medical illness. Quick access to the comparative potency of different antipsychotics can help guide titration to the approximate equivalent dose of CPZ when initiating a medication, switching from 1 antipsychotic to another, or augmenting or combining antipsychotics. Fortunately, many authors, such as Woods2and Davis,3 have codified the dosing ratio equivalences of FGAs and second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs) using CPZ, 100 mg. To help psychiatrists use CPZ dosages as a point of comparison for prescribing other antipsychotics, the Table1,2,4 (page 14) lists dose equivalents for oral FGAs and SGAs based on CPZ, 100 mg. (For information on dose equivalents for injectable antipsychotics, see “Second-generation long-acting injectable antipsychotics: A practical guide,”

While this information cannot replace a psychiatrist’s clinical judgment, it can serve as a clinically useful prescribing tool. In addition to providing this Table, we discuss what you should consider when using these equivalents to switch antipsychotics and estimate the ultimate dose target for effective management of psychotic disorders.

A few caveats

Bioactive equivalent dosages should be targeted as a rough guide when switching from one FGA or SGA to another. Common indications for switching antipsychotics include an inadequate therapeutic response after a medication trial of an adequate dose and duration; relapse of psychosis despite medication adherence; intolerable adverse effects; cost; a new-onset, contraindicating medical illness; and lapses in medication compliance that necessitate a change to IM formulations.5 Keep in mind that medication changes should be tailored to the patient’s specific clinical characteristics.

Several other clinical and pharmacologic variabilities should be kept in mind when switching antipsychotics using CPZ dosage equivalents5,6:

- The therapeutic CPZ equivalent doses may be less precise for SGAs than for FGAs because the equivalents are largely based on dopaminergic blockade instead of cholinergic, serotonergic, or histaminergic systems

- For some antipsychotics, the relationship between dose and potency is nonlinear. For example, as the dosage of haloperidol increases, its relative antipsychotic potency decreases

- Differences in half-lives between 2 agents can add complexity to calculating the dosage equivalent

- Regardless of comparative dosing, before initiating a new antipsychotic, psychiatrists should read the dosing instructions in the FDA-approved package insert, and exercise caution before titrating a new medication to the maximum recommended dose.

1. Danivas V, Venkatasubramanian G. Current perspectives on chlorpromazine equivalents: comparing apples and oranges! Indian J Psychiatry. 2013;55(2):207-208.

2. Woods SW. Chlorpromazine equivalent doses for the newer atypical antipsychotics. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64(6):663-667.

3. Davis JM. Dose equivalence of the anti-psychotic drugs. J Psych Res. 1974;11:65-69.

4. Psychiatric pharmacy essentials: antipsychotic dose equivalents. College of Psychiatric and Neurologic Pharmacists. Accessed February 2, 2021. https://cpnp.org/guideline/essentials/antipsychotic-dose-equivalents

5. Guidelines for antipsychotic medication switches. Humber NHS. Last Reviewed September 2012. Accessed February 2, 2021. https://www.psychdb.com/_media/meds/antipsychotics/nhs_guidelines_antipsychotic_switch.pdf

6. Bobo WV. Switching antipsychotics: why, when, and how? Psychiatric Times. Published March 14, 2013. Accessed February 2, 2021. https://www.psychiatrictimes.com/view/switching-antipsychotics-why-when-and-how

1. Danivas V, Venkatasubramanian G. Current perspectives on chlorpromazine equivalents: comparing apples and oranges! Indian J Psychiatry. 2013;55(2):207-208.

2. Woods SW. Chlorpromazine equivalent doses for the newer atypical antipsychotics. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64(6):663-667.

3. Davis JM. Dose equivalence of the anti-psychotic drugs. J Psych Res. 1974;11:65-69.

4. Psychiatric pharmacy essentials: antipsychotic dose equivalents. College of Psychiatric and Neurologic Pharmacists. Accessed February 2, 2021. https://cpnp.org/guideline/essentials/antipsychotic-dose-equivalents

5. Guidelines for antipsychotic medication switches. Humber NHS. Last Reviewed September 2012. Accessed February 2, 2021. https://www.psychdb.com/_media/meds/antipsychotics/nhs_guidelines_antipsychotic_switch.pdf

6. Bobo WV. Switching antipsychotics: why, when, and how? Psychiatric Times. Published March 14, 2013. Accessed February 2, 2021. https://www.psychiatrictimes.com/view/switching-antipsychotics-why-when-and-how