The National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 20171 has changed military medicine, including substantial reduction in military medical personnel as positions are converted to combat functions. As a result, there will be fewer military dermatologists, which means many US soldiers, sailors, airmen, and marines will seek medical care outside of military treatment facilities. This article highlights some unique treatment considerations in this patient population for our civilian dermatology colleagues.

Medical Readiness

In 2015, General Joseph F. Dunford Jr, 19th Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, made readiness his top priority for the US Armed Forces.2 Readiness refers to service members’ ability to deploy to locations across the globe and perform their military duties with little advanced notice, which requires personnel to be medically prepared at all times to leave home and perform their duties in locations with limited medical support.

Medical readiness is maintaining a unit that is medically able to perform its military function both at home and in a deployed environment. Military members’ medical readiness status is carefully tracked and determined via annual physical, dental, hearing, and vision examinations, as well as human immunodeficiency virus status and immunizations. The readiness status of the unit (ie, the number of troops ready to deploy at any given time) is available to commanders at all levels at any time. Each military branch has tracking systems that allow commanders to know when a member is past due for an examination or if a member’s medical status has changed, making them nondeployable. When a member is nondeployable, it affects the unit’s ability to perform its mission and degrades its readiness. If readiness is suboptimal, the military cannot deploy and complete its missions, which is why readiness is a top priority. The primary function of military medicine is to support the medical readiness of the force.

Deployment Eligibility

A unique aspect of military medicine that can be foreign to civilian physicians is the unit commanders’ authority to request and receive information on military members’ medical conditions as they relate to readiness. Under most circumstances, an individual’s medical information is his/her private information; however, that is not always the case in the military. If a member’s medical status changes and he/she becomes nondeployable, by regulation the commander can be privy to pertinent aspects of that member’s medical condition as it affects unit readiness, including the diagnosis, treatment plan, and prognosis. Commanders need this information to aid in the member’s recovery, ensure training does not impact his/her care, and identify possible need of replacement.

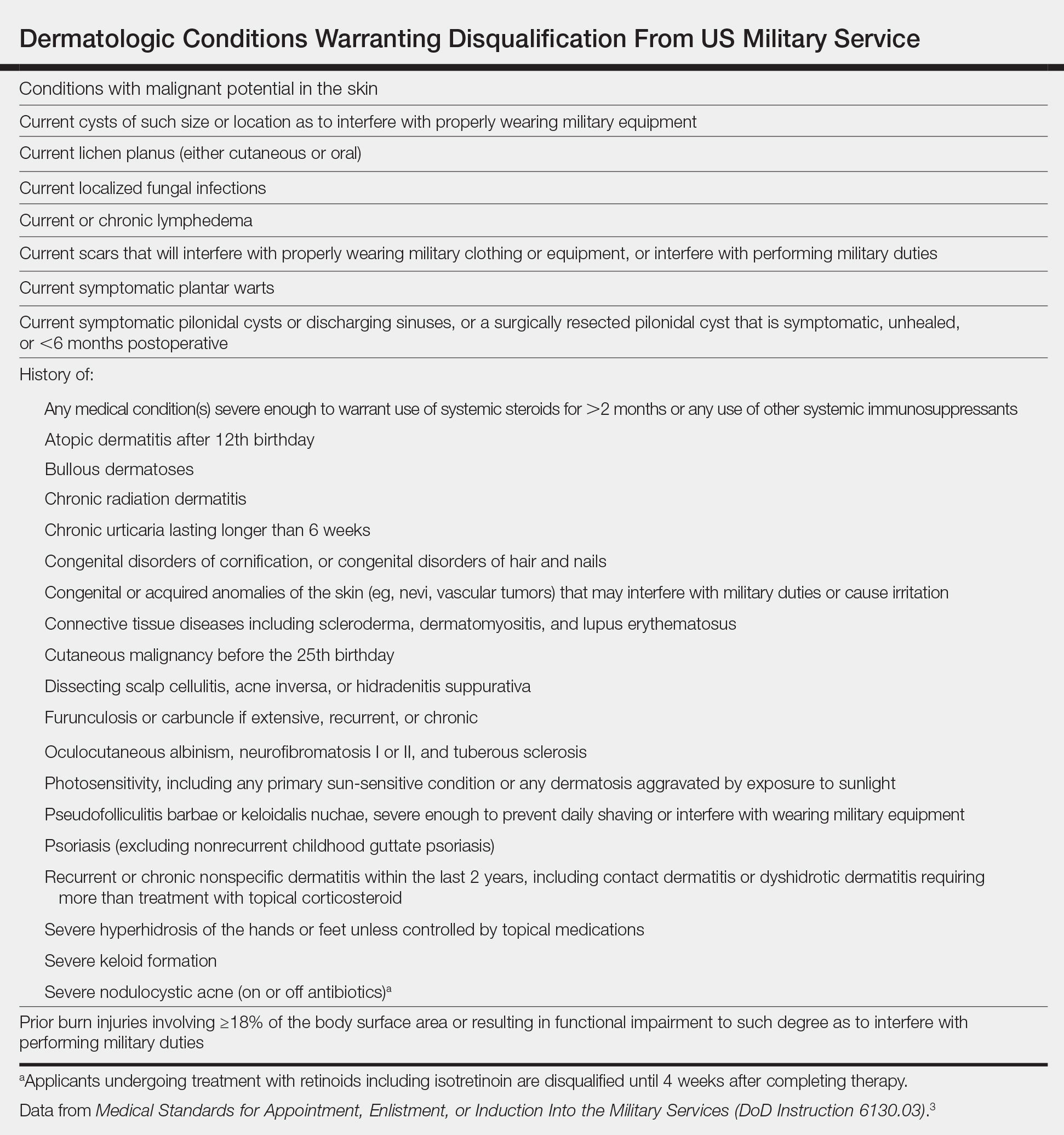

Published accession guidelines are used to determine medical eligibility for service.3 These instructions are organized by major organ systems and broad disease categories. They provide guidance on medically disqualifying conditions. The Table outlines those conditions that apply to the skin.3 Individual military branches may have additional regulations with guidance on medically disqualifying conditions that are job specific. Additional regulations also are available based on an area of military operation that can be more restrictive and specific to those locations.4

Similarly, each military branch has its own retention standards.5,6 Previously healthy individuals can develop new medical conditions, and commanders are notified if a service member becomes medically nondeployable. If a medical condition limits a service member’s ability to deploy, he/she will be evaluated for retention by a medical evaluation board (MEB). Three outcomes are possible: return in current function, retain the service member but retrain in another military occupation, or separate from military service.7 Rarely, waivers are provided so that the service member can return to duty.