Let’s increase our use of IUDs and improve contraceptive effectiveness in this country

Robert L. Barbieri, MD (Editorial, August 2012)

Malpositioned IUDs: When you should intervene

(and when you should not)

Kari P. Braaten, MD, MPH; Alisa B. Goldberg, MD, MPH (August 2012)

The past 20 years have seen an explosion of new contraceptive technologies; women benefit now from a range of effective methods that can satisfy their preferences. Pharmaceutical and biotech companies jumped on board, developing and marketing new hormonal combinations, delivery systems, and inexpensive devices that offer them opportunity for great profit.

Now that many of these newer products have been available for a decade or longer, the combined motivation of women, health-care providers, and industry should have meant better success in preventing undesired pregnancies. Regrettably, we’re moving in the wrong direction: The rate of unintended pregnancy in the United States has increased.

In this Update, we address the sobering reality of the unintended pregnancy rate over 20 years. We then take the opportunity to:

- review new data and guidelines about postpartum and postprocedure insertion of an intrauterine device (IUD)

- explain the latest data and recommendations on venous thrombotic events and combined hormonal methods

- discuss the possibility of an association between depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA) and acquisition of the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV).

What are the national data on unintended pregnancy?

Finer LB, Zolna MR. Unintended pregnancy in the United States: incidence and disparities, 2006. Contraception. 2011;84(5):478–485.

For decades, we’ve been repeating ourselves about the scope of the problem of unintended pregnancy—namely, “about half of all pregnancies in the United States are unintended,” etc. The fact that this rate has not improved in nearly 20 years is, in itself, worrisome; despite a proliferation of methods of contraception (and the hope that added options would cause the high rate of unintended pregnancy to fall), an overall benefit hasn’t been realized.

A small, but very important, decrease in the percentage of pregnancies that are unintended—from 49.2% to 48%—occurred between 1994 and 2001.1 New data assembled by Finer and Zolna show, however, that the percentage has crept back up to 49%.

The unintended pregnancy rate is another way to measure this outcome—reflecting the number of unintended pregnancies for every 1,000 women of reproductive age. The lowest rate (44.7) was seen in 1994; by 2006, the rate had increased to 52—just shy of the highest rate of 52.6 that was reported in the early 1980s.

Why haven’t new methods lowered the unintended pregnancy rate?

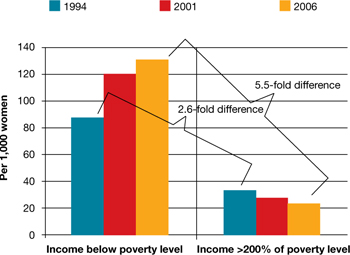

Both unintended pregnancy and abortion affect poorer and younger women disproportionately. In 1994, the unintended pregnancy rate among women who were below the poverty level was 2.6-fold higher than the rate among women who were 200% above the poverty level. That difference in rate increased to 5.5-fold higher by 2006 (FIGURE). The unintended pregnancy rate has increased significantly among poor women while it has continued to decrease among women who are not poor.

The “poverty gap” has been widening in the US rate of unintended pregnancy

Trends shown here are among women aged 15 to 44 years.

Based on data from: Finer LB, Zolna MR. Unintended pregnancy in the United States: Incidence and disparities, 2006. Contraception. 2011;84(5):478–485.

Trends shown here are among women aged 15 to 44 years.

Based on data from: Finer LB, Zolna MR. Unintended pregnancy in the United States: Incidence and disparities, 2006. Contraception. 2011;84(5):478–485.

Why has this happened? Perhaps newer contraceptive methods aren’t being used by, or are not available to, women who are most in need. This regrettable trend is a demonstration that unintended pregnancy is a social issue—that there are, without question, “haves” and “have-nots.”

Black women have an unintended pregnancy rate nearly double that of non-Hispanic white women, and are more likely than non-Hispanic white women to opt for an abortion when faced with an unintended pregnancy. New data also show that, from 2005 to 2008, the number of abortions and the abortion rate in the United States have remained approximately the same.2 While the rate of unintended pregnancy increases, therefore, principally among poor women, more of those pregnancies are being continued.

Contraception, recognized by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention as one of the most important public health advances of the past century, is not having a maximal impact in the United States.3 The primary goal of contraception is to prevent unintended pregnancy; we have not continued to make strides in the last two decades against the unintended pregnancy rate so that women control when they have children and how many they have.

Advertising for contraceptives cannot take the place of education by physicians. Your care of reproductive-age women should include finding an opportunity, at every visit, to address, and educate them on, contraception.

Even more important, primary care physicians—whose ability to offer such highly effective options as IUDs, implants, and sterilization might be limited—need to be better educated to ensure that they 1) provide contraceptive counseling to women and 2) refer patients to a gynecologist or a trained primary care provider who can offer them access to the most appropriate of the full range of methods.

A final note: Continued advocacy of contraception as an important component of primary preventive medicine by the Institute of Medicine (IOM) should mean better support for seasoned providers and new trainees to give contraception and family planning the clinical attention it needs.