Over the past decade gynecologic oncology surgeons have increasingly adopted the technique of sentinel lymph node (SLN) biopsy to stage endometrial cancer. This is supported by evidence that selective removal of the few lymph nodes which are the first to drain the uterus can accurately detect metastatic disease, sparing the patient a complete lymphadenectomy and its associated risks, such as lymphedema.1 The proposed benefits of SLN biopsy are not just its ability to spare the patient removal of dozens of unnecessary lymph nodes, but also the ability to improve upon the detection of previously unrecognized nodal metastases in locations not routinely sampled by lymphadenectomy and by identifying very-low-volume metastatic disease. This is beneficial only, however, if that previously overlooked low-volume disease is clinically significant.

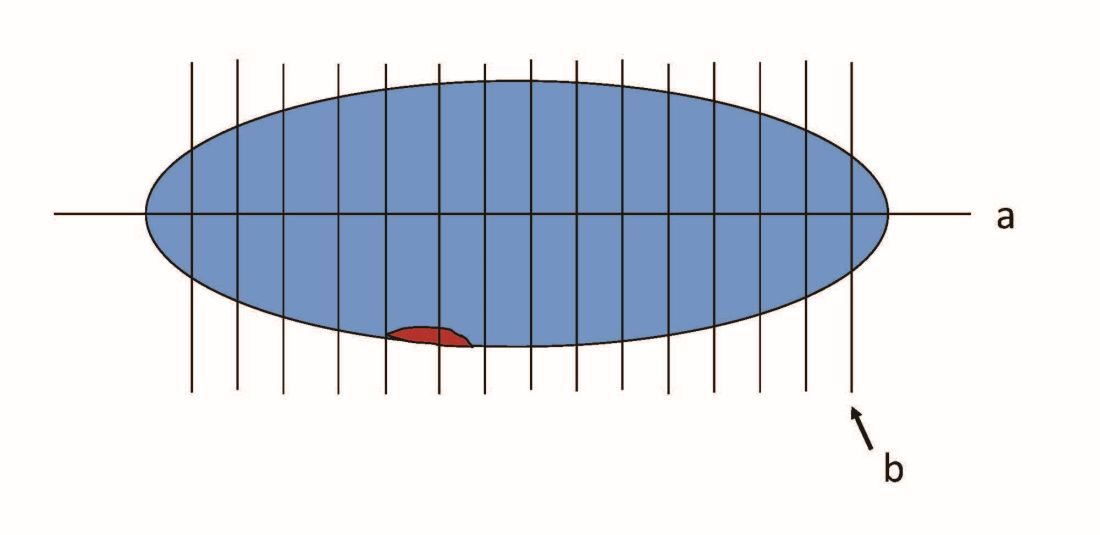

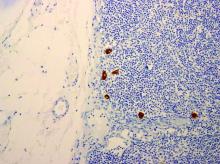

When pathologists evaluate lymph nodes as part of conventional lymphadenectomy, they typically bivalve the lymph node and evaluate with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stains. This technique is capable of detecting metastatic lesions greater than 2 mm, but can miss low-volume disease. In contrast, pathologists process SLNs with much finer sectioning (no greater than 2 mm), and, if the node is larger than 4 mm, they will section it perpendicular to the long axis in a bread-loaf fashion. It is not feasible to perform this ultrasectioning on the large numbers of lymph nodes of a complete lymphadenectomy specimen, but when applied to an SLN it allows pathologists to detect much smaller metastatic foci, the so-called “micrometastases” that are between 0.2 and 2 mm in size, and which typically arise in the subcapsular region of the node. The graphic depicts how a traditional longitudinal cut (a) might miss the micrometastasis that could be identified on the finer perpendicular cuts of ultra-sectioning (b). In addition to the ultrasectioning of the node into smaller slices, the pathologist performs additional immunohistochemistry stains for cytokeratin on sentinel nodes which appear negative on preliminary H&E stains. This allows the pathologist to identify even smaller clusters of malignant cells that are less than 0.2 mm, or individual cancer cells, so-called “isolated tumor cells” (ITCs) as shown in the photo. Most SLN series identify that approximately half of their “positive” lymph nodes are low-volume disease (micrometastases and ITCs). ITCs make up the majority of these cases, typically three-quarters.

Clinicians might be reassured by the discovery of low-volume metastatic disease, perceiving that the added attention afforded by the SLN approach helped them to identify metastases that might otherwise have been missed and therefore not treated. This is because node-positive (stage IIIC) disease is not cured by surgery or radiation alone and requires the addition of chemotherapy for survival benefit.2 Alternatively, there is no clear survival benefit derived from treating stage I high/intermediate cancers with chemotherapy, and therefore, the prescription of chemotherapy hinges upon reliable identification of extrauterine disease on pathology.3

It would make sense that if SLNs are more effective in identifying metastatic disease, clinicians who practice SLN biopsy would identify it more of the time. This appears to be the case with a trend towards upstaging in patients who undergo SLN biopsy, compared with those undergoing complete lymphadenectomy.4 It should also follow that if this increased detection of metastatic disease was clinically relevant, we would observe a corresponding improvement in survival outcomes. If not, then the additional identification of low-volume disease may not be value added: imparting toxicity of adjuvant therapy without survival benefit.

Micrometastases (foci sized 0.2-2 mm) are not a new phenomenon to the SLN era. Low-volume lesions were occasionally detected with routine nodal processing and H&E stains. Attention wasn’t paid to nodal volume categorization in pathology reports prior to the SLN era. These were usually reported collectively as stage IIIC disease. It would make sense to continue to approach micrometastases in a manner similar to what we have always done, recognizing that it may represent a continuum of nodal macrometastases. In contrast, ITCs are rarely detected with routine pathologic processing. Perhaps they are less within a continuum of nodal metastases, and more within the continuum of lymphovascular space invasion. We know that ITCs are significantly associated with the cofinding of this uterine phenomenon, which itself is considered a significant risk factor for local recurrence.5

Series have consistently shown the outcomes of women with ITCs to be favorable, compared with those with micrometastases or macrometastases.5,6 However, most retrospective series that evaluated the outcomes of patients with respect to volume of metastatic disease have high rates of treatment of ITCs with chemotherapy, radiotherapy, or both.6 This may mask and confuse whether there is any intrinsically favorable prognostic virtue of ITCs, compared with larger metastatic foci. When ITCs are untreated, it would appear that the rates and patterns of recurrence appear similar to those with negative SLNs, with the caveat that these series all include small numbers.5,7 This would suggest that women with ITCs do not need additional therapy beyond what would be prescribed for their uterine risk factors.

Further supporting the notion that ITCs have more favorable prognosis is that, while SLN biopsy is associated with a higher detection of nodal metastatic disease, it is not necessarily associated with improved survival when compared with complete lymphadenectomy in retrospective series.8 This suggests that finding and treating ITCs may not positively affect outcomes. Or possibly it is a result of inadequate statistical power to show a small benefit should one exist. It is especially difficult to differentiate micrometastases and ITCs with respect to treatment outcomes. Given that ITCs make up the majority of low-volume nodal disease detected through the SLN technique, any potential benefit of increased capture and treatment of the more substantial micrometastases is not likely to be captured. As a result, most series tend to lump patients with micrometastases with those with ITCs in their analysis of patient outcomes. This may be a mistake.

Clearly more research needs to be performed to definitively address the clinical significance of ITCs. While it would be ideal to conduct a prospective trial in which patients with ITCs are randomized to therapy or observation, in reality the scope of such a trial makes it impractical. ITCs are detected in only approximately 5% of all the patients with endometrial cancer, and given that outcomes for this group are, in general, good, it would require enrollment of tens of thousands of patients to establish a statistically satisfactory result. Therefore it is likely that we will need to rely on the results of large retrospective, population-based, observational series to determine if the identification and treatment of ITCs adds value and superior outcomes to patients. In addition, we are making leaps in better understanding the molecular profile of endometrial cancers and how we might incorporate this data with histology and staging results to create treatment algorithms, much like what has been developed for breast cancer. This is likely where the future lies in interpreting the results of staging. In the meantime, it seems reasonable to collect the data regarding volume of metastatic disease including the presence of ITCs, making shared treatment decisions with the patient regarding the addition of adjuvant therapy, recognizing that

Dr. Rossi is assistant professor in the division of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. She has no conflicts of interest to declare. Email her at obnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. Lancet Oncol. 2017 Mar;18(3):384-92.

2. J Clin Oncol. 2006 Jan 1;24(1):36-44.

3. J Clin Oncol. 2019 Jul 20;37(21):1810-8.

4. Clin Transl Oncol. 2019. doi: 10.1007/s12094-019-02249-x.

5. Gynecol Oncol. 2017 Aug;146(2):240-6.

6. Ann Surg Oncol. 2016 May;23(5):1653-9.