User login

The Diagnosis: Herpes Zoster

Herpes zoster is a common infection that clinically presents with moderate to intense pain in the involved dermatome (1–3 days before the outbreak1) followed by a unilateral dermatomal eruption. The most common sites of involvement include the trunk (dermatomes T3–L2) and upper face (dermatome V1).2 Herpes zoster characteristically begins as erythematous macules and papules that progress to vesicles and sometimes pustules, which subsequently crust over (7–10 days after the initial outbreak).1 Regional lymphadenopathy is present in most cases. Due to the classic presentation of herpes zoster, clinical diagnosis is the mainstay for most cases. Although it can present in any age group, herpes zoster is most commonly associated with advancing age.3

During the course of primary varicella infection, the herpes virus spreads from infected lesions to the contiguous endings of sensory nerves and travels to the dorsal root ganglion cells where it remains latent.1 It is hypothesized that cell-mediated immunity suppresses viral activity and maintains viral latency. A decline in varicella zoster virus–specific cell-mediated immunity can result in reactivation of the latent virus.1 The virus is then transported to the skin from the dorsal root ganglion via myelinated nerves, which terminate at the isthmus of hair follicles, and subsequent infection of the folliculosebaceous unit occurs.4

Laboratory tests that can assist in the diagnosis of herpes zoster, especially atypical cases, include Tzanck smear and viral culture of the vesicle fluid.1 When vesicles are not present, biopsy of the lesion followed by immunohistochemical staining and polymerase chain reaction assay can aid in the diagnosis. The differential diagnosis for our patient included pseudolymphoma, herpes simplex virus, lymphomatoid papulosis, sarcoidosis, trigeminal trophic syndrome, and Sweet syndrome.

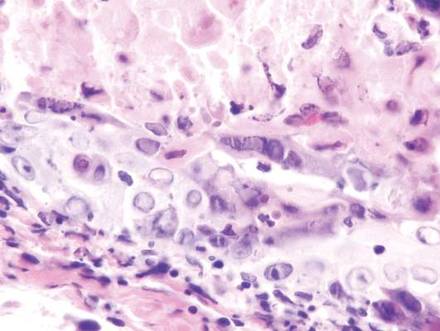

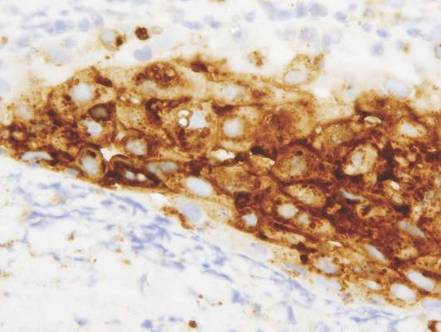

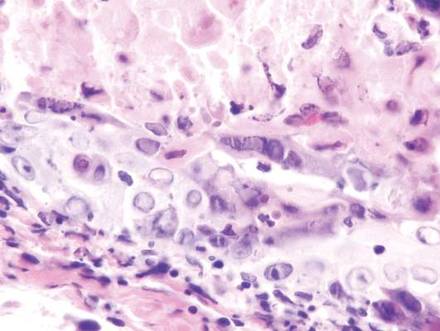

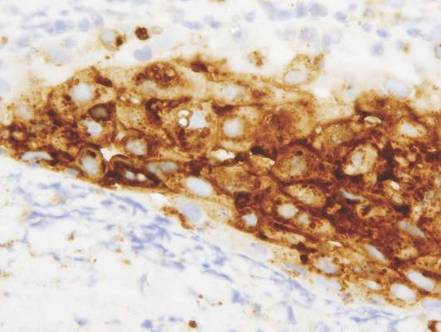

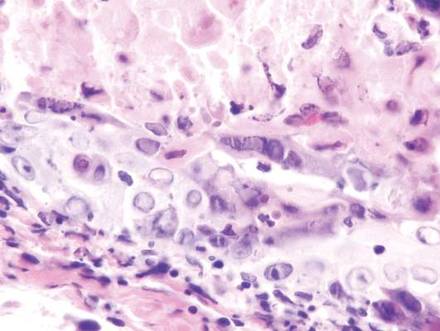

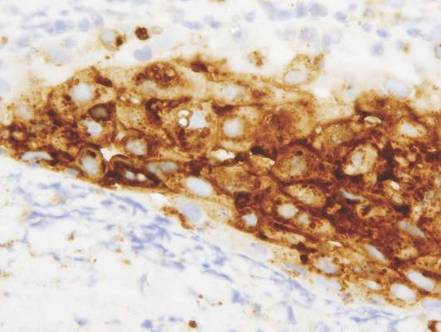

Vesicles were not present in our patient, but the dermatomal nature of the eruption and the pain she experienced made the clinical scenario suspicious for herpes zoster. A 4-mm punch biopsy of a single folliculosebaceous unit revealed herpetic, cytopathic features including prominent keratinocyte necrosis involving sebaceous, isthmic, and infundibular epithelium; ballooning of epithelial cells with steel gray nuclei; and multinucleation with nuclear molding (Figure 1). Strong nuclear and cytoplasmic staining was seen in the affected keratinocytes under anti–varicella zoster virus immunohistochemical analysis (Figure 2). Staining for herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2 was negative. Within days of starting valacyclovir 1000 mg (every 8 hours for 1 week), the patient’s symptoms resolved.

|  | |

|

|

Atypical presentations of herpes zoster (eg, presentations that are not completely dermatomal) are becoming more common. Herpetic infections should always be in the differential diagnosis for cutaneous ulcerations. Misdiagnosis of herpes zoster due to atypical features is common and can delay prompt and adequate treatment.

- Rockley PF, Tyring SK. Pathophysiology and clinical manifestations of varicella zoster virus infections. Int J Dermatol. 1994;33:227-232.

- Chen TM, George S, Woodruff CA, et al. Clinical manifestations of varicella-zoster virus infection. Dermatol Clin. 2002;20:267-282.

- Hope-Simpson RE. The nature of herpes zoster: a long-term study and a new hypothesis. Proc R Soc Med. 1965;58:9-20.

- Walsh N, Boutilier R, Glasgow D, et al. Exclusive involvement of folliculosebaceous units by herpes: a reflection of early herpes zoster. Am J Dermatopathol. 2005;27:189-194.

The Diagnosis: Herpes Zoster

Herpes zoster is a common infection that clinically presents with moderate to intense pain in the involved dermatome (1–3 days before the outbreak1) followed by a unilateral dermatomal eruption. The most common sites of involvement include the trunk (dermatomes T3–L2) and upper face (dermatome V1).2 Herpes zoster characteristically begins as erythematous macules and papules that progress to vesicles and sometimes pustules, which subsequently crust over (7–10 days after the initial outbreak).1 Regional lymphadenopathy is present in most cases. Due to the classic presentation of herpes zoster, clinical diagnosis is the mainstay for most cases. Although it can present in any age group, herpes zoster is most commonly associated with advancing age.3

During the course of primary varicella infection, the herpes virus spreads from infected lesions to the contiguous endings of sensory nerves and travels to the dorsal root ganglion cells where it remains latent.1 It is hypothesized that cell-mediated immunity suppresses viral activity and maintains viral latency. A decline in varicella zoster virus–specific cell-mediated immunity can result in reactivation of the latent virus.1 The virus is then transported to the skin from the dorsal root ganglion via myelinated nerves, which terminate at the isthmus of hair follicles, and subsequent infection of the folliculosebaceous unit occurs.4

Laboratory tests that can assist in the diagnosis of herpes zoster, especially atypical cases, include Tzanck smear and viral culture of the vesicle fluid.1 When vesicles are not present, biopsy of the lesion followed by immunohistochemical staining and polymerase chain reaction assay can aid in the diagnosis. The differential diagnosis for our patient included pseudolymphoma, herpes simplex virus, lymphomatoid papulosis, sarcoidosis, trigeminal trophic syndrome, and Sweet syndrome.

Vesicles were not present in our patient, but the dermatomal nature of the eruption and the pain she experienced made the clinical scenario suspicious for herpes zoster. A 4-mm punch biopsy of a single folliculosebaceous unit revealed herpetic, cytopathic features including prominent keratinocyte necrosis involving sebaceous, isthmic, and infundibular epithelium; ballooning of epithelial cells with steel gray nuclei; and multinucleation with nuclear molding (Figure 1). Strong nuclear and cytoplasmic staining was seen in the affected keratinocytes under anti–varicella zoster virus immunohistochemical analysis (Figure 2). Staining for herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2 was negative. Within days of starting valacyclovir 1000 mg (every 8 hours for 1 week), the patient’s symptoms resolved.

|  | |

|

|

Atypical presentations of herpes zoster (eg, presentations that are not completely dermatomal) are becoming more common. Herpetic infections should always be in the differential diagnosis for cutaneous ulcerations. Misdiagnosis of herpes zoster due to atypical features is common and can delay prompt and adequate treatment.

The Diagnosis: Herpes Zoster

Herpes zoster is a common infection that clinically presents with moderate to intense pain in the involved dermatome (1–3 days before the outbreak1) followed by a unilateral dermatomal eruption. The most common sites of involvement include the trunk (dermatomes T3–L2) and upper face (dermatome V1).2 Herpes zoster characteristically begins as erythematous macules and papules that progress to vesicles and sometimes pustules, which subsequently crust over (7–10 days after the initial outbreak).1 Regional lymphadenopathy is present in most cases. Due to the classic presentation of herpes zoster, clinical diagnosis is the mainstay for most cases. Although it can present in any age group, herpes zoster is most commonly associated with advancing age.3

During the course of primary varicella infection, the herpes virus spreads from infected lesions to the contiguous endings of sensory nerves and travels to the dorsal root ganglion cells where it remains latent.1 It is hypothesized that cell-mediated immunity suppresses viral activity and maintains viral latency. A decline in varicella zoster virus–specific cell-mediated immunity can result in reactivation of the latent virus.1 The virus is then transported to the skin from the dorsal root ganglion via myelinated nerves, which terminate at the isthmus of hair follicles, and subsequent infection of the folliculosebaceous unit occurs.4

Laboratory tests that can assist in the diagnosis of herpes zoster, especially atypical cases, include Tzanck smear and viral culture of the vesicle fluid.1 When vesicles are not present, biopsy of the lesion followed by immunohistochemical staining and polymerase chain reaction assay can aid in the diagnosis. The differential diagnosis for our patient included pseudolymphoma, herpes simplex virus, lymphomatoid papulosis, sarcoidosis, trigeminal trophic syndrome, and Sweet syndrome.

Vesicles were not present in our patient, but the dermatomal nature of the eruption and the pain she experienced made the clinical scenario suspicious for herpes zoster. A 4-mm punch biopsy of a single folliculosebaceous unit revealed herpetic, cytopathic features including prominent keratinocyte necrosis involving sebaceous, isthmic, and infundibular epithelium; ballooning of epithelial cells with steel gray nuclei; and multinucleation with nuclear molding (Figure 1). Strong nuclear and cytoplasmic staining was seen in the affected keratinocytes under anti–varicella zoster virus immunohistochemical analysis (Figure 2). Staining for herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2 was negative. Within days of starting valacyclovir 1000 mg (every 8 hours for 1 week), the patient’s symptoms resolved.

|  | |

|

|

Atypical presentations of herpes zoster (eg, presentations that are not completely dermatomal) are becoming more common. Herpetic infections should always be in the differential diagnosis for cutaneous ulcerations. Misdiagnosis of herpes zoster due to atypical features is common and can delay prompt and adequate treatment.

- Rockley PF, Tyring SK. Pathophysiology and clinical manifestations of varicella zoster virus infections. Int J Dermatol. 1994;33:227-232.

- Chen TM, George S, Woodruff CA, et al. Clinical manifestations of varicella-zoster virus infection. Dermatol Clin. 2002;20:267-282.

- Hope-Simpson RE. The nature of herpes zoster: a long-term study and a new hypothesis. Proc R Soc Med. 1965;58:9-20.

- Walsh N, Boutilier R, Glasgow D, et al. Exclusive involvement of folliculosebaceous units by herpes: a reflection of early herpes zoster. Am J Dermatopathol. 2005;27:189-194.

- Rockley PF, Tyring SK. Pathophysiology and clinical manifestations of varicella zoster virus infections. Int J Dermatol. 1994;33:227-232.

- Chen TM, George S, Woodruff CA, et al. Clinical manifestations of varicella-zoster virus infection. Dermatol Clin. 2002;20:267-282.

- Hope-Simpson RE. The nature of herpes zoster: a long-term study and a new hypothesis. Proc R Soc Med. 1965;58:9-20.

- Walsh N, Boutilier R, Glasgow D, et al. Exclusive involvement of folliculosebaceous units by herpes: a reflection of early herpes zoster. Am J Dermatopathol. 2005;27:189-194.

A 32-year-old woman with no remarkable medical history presented with a progressively worsening erythematous and edematous plaque on the right cheek of 8 days’ duration. She had previously been treated by her primary care physician with cephalexin for 3 days and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole for 2 days, which resulted in “flattening” of the plaque, but the lesion did not resolve. She was referred to our dermatology clinic for further evaluation. She denied any trauma to the cheek or scratching of the lesion. On physical examination, a 2-cm pink, erythematous, edematous plaque with a central eschar was noted on the right cheek with crusting of the right nasal wall.