User login

Firm Abdominal Papule

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Metastatic Gastric Carcinoma

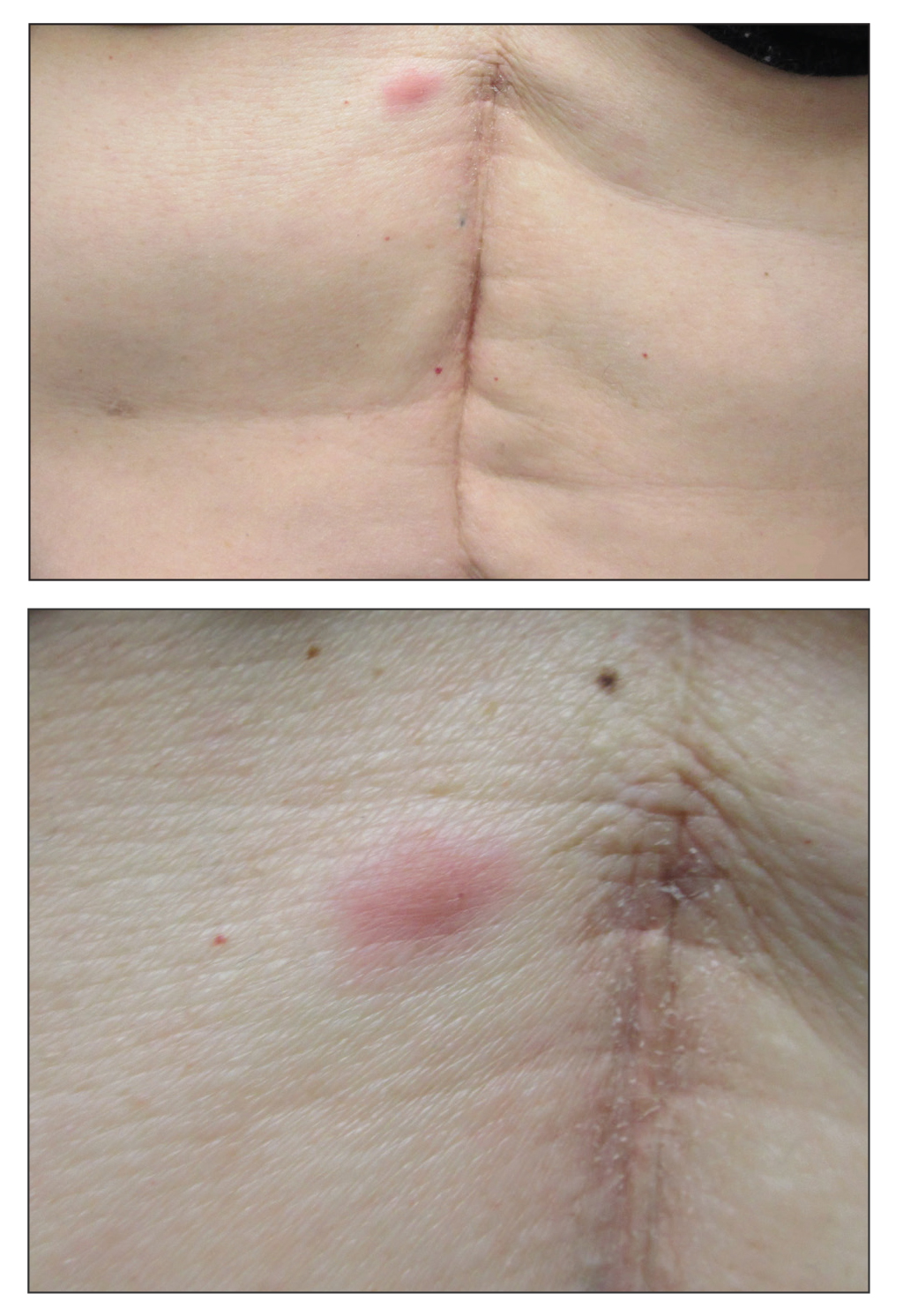

Cutaneous metastasis of primary gastric carcinoma is a rare occurrence, with the more common metastatic sites being the lymph nodes, liver, and peritoneal cavity. The incidence of visceral neoplasm metastasis to the skin ranges from 0.7% to 9% and is less than 1% for upper digestive tract carcinomas.1 Cutaneous metastases make up 2% of all tumors of the skin and commonly are located near the site of the primary tumor.2 The most common cutaneous metastasis sites for gastric carcinoma include the neck, chest, and head.3 One of the more typical sites of cutaneous metastasis from gastric cancer is the umbilicus (ie, Sister Mary Joseph nodule). Cutaneous metastases from gastric carcinoma commonly present as asymptomatic hyperpigmented nodules.1,3

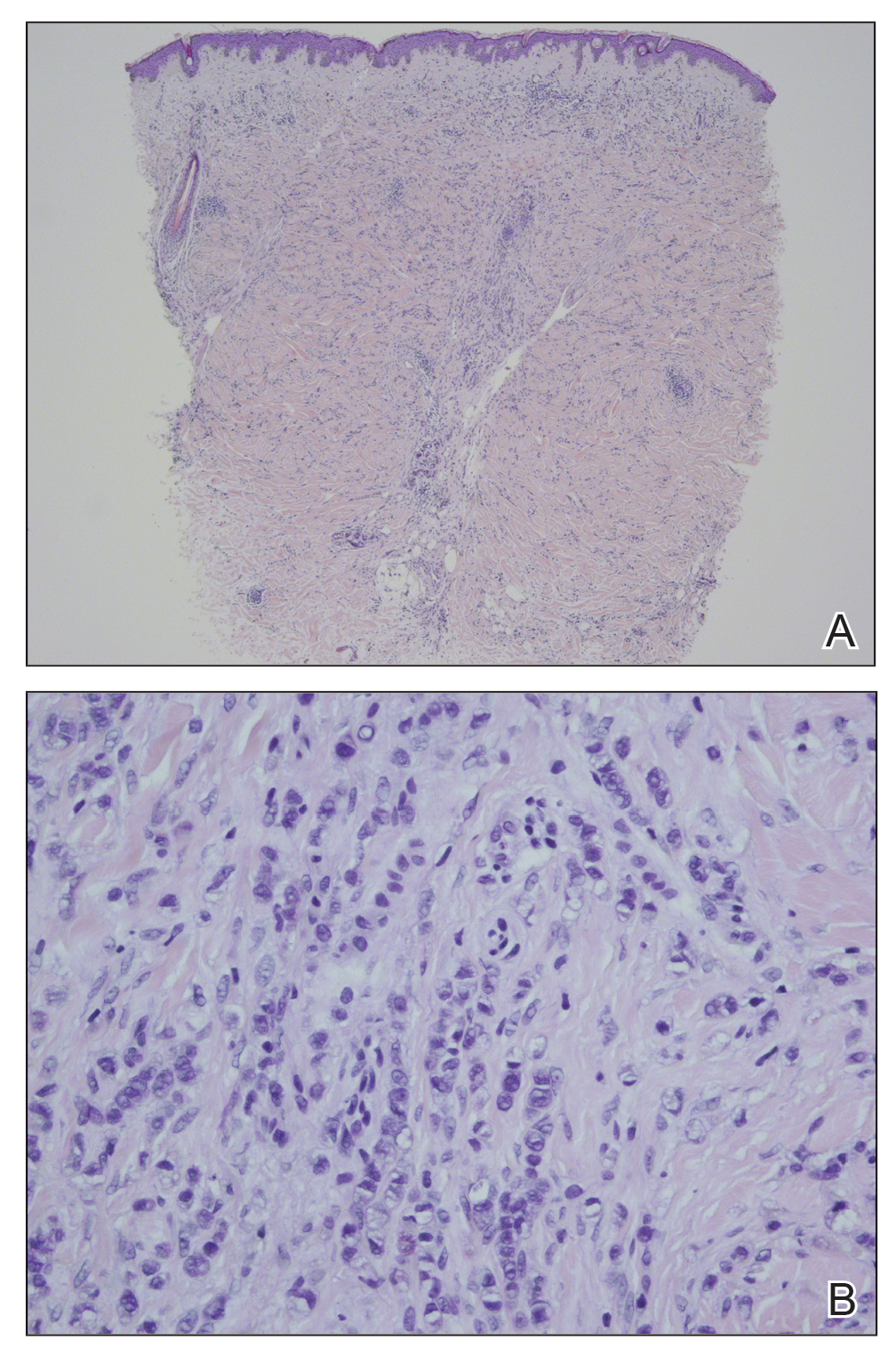

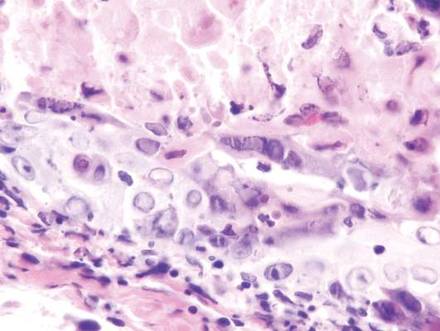

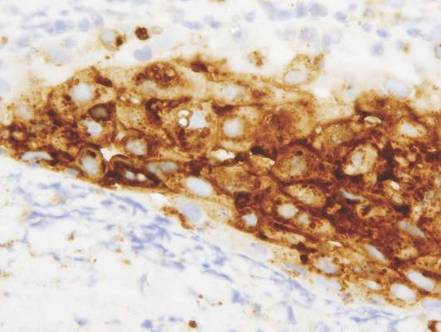

In our patient, histopathologic sections showed diffuse infiltration of the dermis by atypical polygonal/round cells arranged in cords and small aggregates. Some of the neoplastic cells had signet ring morphology (Figure). Tumor cells demonstrated positive immunostaining for CDX2, villin, CAM 5.2, and epithelial membrane antigen; they were negative for S-100, MART-1 (melanoma-associated antigen recognized by T cells 1), leukocyte common antigen, gross cystic disease fluid protein 15, estrogen and progesterone receptor, and HER2/neu (human epidermal growth factor receptor 2).

Our patient's presentation was rare in that she developed an asymptomatic erythematous papule on the skin of the abdomen. However, her history of stage IIIB gastric adenocarcinoma in conjunction with the clinical picture and microscopic findings were most consistent with metastatic carcinoma of gastrointestinal origin. The histologic hallmarks of cutaneous metastatic gastric carcinoma include aggregates of neoplastic cells arranged in cords, sometimes forming glands, embedded in a fibrous stroma. Tumor cells may demonstrate signet ring morphology. These unique histologic findings, as well as positive immunostaining for CDX2, villin, CAM 5.2, and epithelial membrane antigen, rule out other potential diagnoses for an asymptomatic solitary papule.

Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans presents as an asymptomatic, slow-growing, indurated papule or plaque that develops into a red or brownish nodule. Histologically, dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans is characterized by spindled cells, few mitotic figures, infiltration of the subcutaneous tissue in a honeycomblike pattern, and obliteration of the adnexal structures.4

Cutaneous B-cell lymphoma (CBCL) can present as single or multiple red papules or nodules located on the trunk, face, or extremities. Histologically, CBCL would show a nodular or diffuse infiltrate throughout the dermis, frequently with accentuation in the deep reticular dermis, sparing of the epidermis, and the presence of a grenz zone. The infiltrate in CBCL consists of CD20+, CD19+, and CD79a+ B cells. Identification of a monoclonal B-cell population either by immunohistochemistry or polymerase chain reaction would further support a diagnosis of CBCL.4 These specific histologic findings and the immunohistochemical staining pattern helped rule out CBCL as the diagnosis in our patient.

Amelanotic melanomas present as flesh-colored to light pink papules, making them especially challenging to diagnose clinically. Asymmetrical, poorly circumscribed nests of atypical melanocytes as well as single melanocytes within the epidermis and dermis are seen histologically; mitotic figures are common. Immunohistochemical staining for melanoma includes S-100, human melanoma black 45, MART-1/Melan-A, tyrosinase, and microphthalmia-associated transcription factor 1.4

Neurothekeomas can present as asymptomatic, solitary, flesh-colored papules located on the head, neck, and upper trunk. Histologically, neurothekeomas have a distinct appearance consisting of a well-defined mass composed of variable-sized lobules of spindled and epithelioid cells dispersed in a myxoid stroma within the reticular dermis.4 These specific histologic findings helped rule out neurothekeoma in our patient.

Following the diagnosis of cutaneous metastatic gastric carcinoma in our patient, positron emission tomography and computed tomography of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis were unremarkable for distant disease. Subsequently, the patient underwent surgical excision of the papule with clear margins, followed by a short course of radiation therapy. She currently is under close monitoring but remains in remission with no new cutaneous manifestations of the gastric carcinoma.

- Erdemir A, Atilganoglu U, Onsun N, et al. Cutaneous metastases from gastric adenocarcinoma. Indian J Dermatol. 2011;56:236-237.

- Junqueira AL, Corbett AM, Oliveira Filho Jd, et al. Cutaneous metastasis from gastrointestinal adenocarcinoma of unknown primary origin. An Bras Dermatol. 2015;90:564-566.

- Cesaretti M, Malerba M, Basso V, et al. Cutaneous metastasis from primary gastric cancer: a case report and review of the literature. Cutis. 2014;93:E9-E13.

- Bolognia J, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV. Dermatology. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2012.

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Metastatic Gastric Carcinoma

Cutaneous metastasis of primary gastric carcinoma is a rare occurrence, with the more common metastatic sites being the lymph nodes, liver, and peritoneal cavity. The incidence of visceral neoplasm metastasis to the skin ranges from 0.7% to 9% and is less than 1% for upper digestive tract carcinomas.1 Cutaneous metastases make up 2% of all tumors of the skin and commonly are located near the site of the primary tumor.2 The most common cutaneous metastasis sites for gastric carcinoma include the neck, chest, and head.3 One of the more typical sites of cutaneous metastasis from gastric cancer is the umbilicus (ie, Sister Mary Joseph nodule). Cutaneous metastases from gastric carcinoma commonly present as asymptomatic hyperpigmented nodules.1,3

In our patient, histopathologic sections showed diffuse infiltration of the dermis by atypical polygonal/round cells arranged in cords and small aggregates. Some of the neoplastic cells had signet ring morphology (Figure). Tumor cells demonstrated positive immunostaining for CDX2, villin, CAM 5.2, and epithelial membrane antigen; they were negative for S-100, MART-1 (melanoma-associated antigen recognized by T cells 1), leukocyte common antigen, gross cystic disease fluid protein 15, estrogen and progesterone receptor, and HER2/neu (human epidermal growth factor receptor 2).

Our patient's presentation was rare in that she developed an asymptomatic erythematous papule on the skin of the abdomen. However, her history of stage IIIB gastric adenocarcinoma in conjunction with the clinical picture and microscopic findings were most consistent with metastatic carcinoma of gastrointestinal origin. The histologic hallmarks of cutaneous metastatic gastric carcinoma include aggregates of neoplastic cells arranged in cords, sometimes forming glands, embedded in a fibrous stroma. Tumor cells may demonstrate signet ring morphology. These unique histologic findings, as well as positive immunostaining for CDX2, villin, CAM 5.2, and epithelial membrane antigen, rule out other potential diagnoses for an asymptomatic solitary papule.

Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans presents as an asymptomatic, slow-growing, indurated papule or plaque that develops into a red or brownish nodule. Histologically, dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans is characterized by spindled cells, few mitotic figures, infiltration of the subcutaneous tissue in a honeycomblike pattern, and obliteration of the adnexal structures.4

Cutaneous B-cell lymphoma (CBCL) can present as single or multiple red papules or nodules located on the trunk, face, or extremities. Histologically, CBCL would show a nodular or diffuse infiltrate throughout the dermis, frequently with accentuation in the deep reticular dermis, sparing of the epidermis, and the presence of a grenz zone. The infiltrate in CBCL consists of CD20+, CD19+, and CD79a+ B cells. Identification of a monoclonal B-cell population either by immunohistochemistry or polymerase chain reaction would further support a diagnosis of CBCL.4 These specific histologic findings and the immunohistochemical staining pattern helped rule out CBCL as the diagnosis in our patient.

Amelanotic melanomas present as flesh-colored to light pink papules, making them especially challenging to diagnose clinically. Asymmetrical, poorly circumscribed nests of atypical melanocytes as well as single melanocytes within the epidermis and dermis are seen histologically; mitotic figures are common. Immunohistochemical staining for melanoma includes S-100, human melanoma black 45, MART-1/Melan-A, tyrosinase, and microphthalmia-associated transcription factor 1.4

Neurothekeomas can present as asymptomatic, solitary, flesh-colored papules located on the head, neck, and upper trunk. Histologically, neurothekeomas have a distinct appearance consisting of a well-defined mass composed of variable-sized lobules of spindled and epithelioid cells dispersed in a myxoid stroma within the reticular dermis.4 These specific histologic findings helped rule out neurothekeoma in our patient.

Following the diagnosis of cutaneous metastatic gastric carcinoma in our patient, positron emission tomography and computed tomography of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis were unremarkable for distant disease. Subsequently, the patient underwent surgical excision of the papule with clear margins, followed by a short course of radiation therapy. She currently is under close monitoring but remains in remission with no new cutaneous manifestations of the gastric carcinoma.

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Metastatic Gastric Carcinoma

Cutaneous metastasis of primary gastric carcinoma is a rare occurrence, with the more common metastatic sites being the lymph nodes, liver, and peritoneal cavity. The incidence of visceral neoplasm metastasis to the skin ranges from 0.7% to 9% and is less than 1% for upper digestive tract carcinomas.1 Cutaneous metastases make up 2% of all tumors of the skin and commonly are located near the site of the primary tumor.2 The most common cutaneous metastasis sites for gastric carcinoma include the neck, chest, and head.3 One of the more typical sites of cutaneous metastasis from gastric cancer is the umbilicus (ie, Sister Mary Joseph nodule). Cutaneous metastases from gastric carcinoma commonly present as asymptomatic hyperpigmented nodules.1,3

In our patient, histopathologic sections showed diffuse infiltration of the dermis by atypical polygonal/round cells arranged in cords and small aggregates. Some of the neoplastic cells had signet ring morphology (Figure). Tumor cells demonstrated positive immunostaining for CDX2, villin, CAM 5.2, and epithelial membrane antigen; they were negative for S-100, MART-1 (melanoma-associated antigen recognized by T cells 1), leukocyte common antigen, gross cystic disease fluid protein 15, estrogen and progesterone receptor, and HER2/neu (human epidermal growth factor receptor 2).

Our patient's presentation was rare in that she developed an asymptomatic erythematous papule on the skin of the abdomen. However, her history of stage IIIB gastric adenocarcinoma in conjunction with the clinical picture and microscopic findings were most consistent with metastatic carcinoma of gastrointestinal origin. The histologic hallmarks of cutaneous metastatic gastric carcinoma include aggregates of neoplastic cells arranged in cords, sometimes forming glands, embedded in a fibrous stroma. Tumor cells may demonstrate signet ring morphology. These unique histologic findings, as well as positive immunostaining for CDX2, villin, CAM 5.2, and epithelial membrane antigen, rule out other potential diagnoses for an asymptomatic solitary papule.

Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans presents as an asymptomatic, slow-growing, indurated papule or plaque that develops into a red or brownish nodule. Histologically, dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans is characterized by spindled cells, few mitotic figures, infiltration of the subcutaneous tissue in a honeycomblike pattern, and obliteration of the adnexal structures.4

Cutaneous B-cell lymphoma (CBCL) can present as single or multiple red papules or nodules located on the trunk, face, or extremities. Histologically, CBCL would show a nodular or diffuse infiltrate throughout the dermis, frequently with accentuation in the deep reticular dermis, sparing of the epidermis, and the presence of a grenz zone. The infiltrate in CBCL consists of CD20+, CD19+, and CD79a+ B cells. Identification of a monoclonal B-cell population either by immunohistochemistry or polymerase chain reaction would further support a diagnosis of CBCL.4 These specific histologic findings and the immunohistochemical staining pattern helped rule out CBCL as the diagnosis in our patient.

Amelanotic melanomas present as flesh-colored to light pink papules, making them especially challenging to diagnose clinically. Asymmetrical, poorly circumscribed nests of atypical melanocytes as well as single melanocytes within the epidermis and dermis are seen histologically; mitotic figures are common. Immunohistochemical staining for melanoma includes S-100, human melanoma black 45, MART-1/Melan-A, tyrosinase, and microphthalmia-associated transcription factor 1.4

Neurothekeomas can present as asymptomatic, solitary, flesh-colored papules located on the head, neck, and upper trunk. Histologically, neurothekeomas have a distinct appearance consisting of a well-defined mass composed of variable-sized lobules of spindled and epithelioid cells dispersed in a myxoid stroma within the reticular dermis.4 These specific histologic findings helped rule out neurothekeoma in our patient.

Following the diagnosis of cutaneous metastatic gastric carcinoma in our patient, positron emission tomography and computed tomography of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis were unremarkable for distant disease. Subsequently, the patient underwent surgical excision of the papule with clear margins, followed by a short course of radiation therapy. She currently is under close monitoring but remains in remission with no new cutaneous manifestations of the gastric carcinoma.

- Erdemir A, Atilganoglu U, Onsun N, et al. Cutaneous metastases from gastric adenocarcinoma. Indian J Dermatol. 2011;56:236-237.

- Junqueira AL, Corbett AM, Oliveira Filho Jd, et al. Cutaneous metastasis from gastrointestinal adenocarcinoma of unknown primary origin. An Bras Dermatol. 2015;90:564-566.

- Cesaretti M, Malerba M, Basso V, et al. Cutaneous metastasis from primary gastric cancer: a case report and review of the literature. Cutis. 2014;93:E9-E13.

- Bolognia J, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV. Dermatology. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2012.

- Erdemir A, Atilganoglu U, Onsun N, et al. Cutaneous metastases from gastric adenocarcinoma. Indian J Dermatol. 2011;56:236-237.

- Junqueira AL, Corbett AM, Oliveira Filho Jd, et al. Cutaneous metastasis from gastrointestinal adenocarcinoma of unknown primary origin. An Bras Dermatol. 2015;90:564-566.

- Cesaretti M, Malerba M, Basso V, et al. Cutaneous metastasis from primary gastric cancer: a case report and review of the literature. Cutis. 2014;93:E9-E13.

- Bolognia J, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV. Dermatology. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2012.

A 53-year-old woman with a history of melanoma on the right thigh, stage II Hodgkin lymphoma, and stage IIIB gastric adenocarcinoma treated with a distal gastrectomy presented with an asymptomatic but persistent skin lesion on the abdomen of 2 months' duration. The lesion arose spontaneously 6 months prior and had increased in size during that time. Physical examination revealed a 6-mm, solitary, firm, erythematous papule on the skin of the right upper quadrant of the abdomen. The patient was otherwise healthy, and a review of systems did not reveal any abnormalities. A punch biopsy was submitted for histopathologic review.

What Is Your Diagnosis? Herpes Zoster

The Diagnosis: Herpes Zoster

Herpes zoster is a common infection that clinically presents with moderate to intense pain in the involved dermatome (1–3 days before the outbreak1) followed by a unilateral dermatomal eruption. The most common sites of involvement include the trunk (dermatomes T3–L2) and upper face (dermatome V1).2 Herpes zoster characteristically begins as erythematous macules and papules that progress to vesicles and sometimes pustules, which subsequently crust over (7–10 days after the initial outbreak).1 Regional lymphadenopathy is present in most cases. Due to the classic presentation of herpes zoster, clinical diagnosis is the mainstay for most cases. Although it can present in any age group, herpes zoster is most commonly associated with advancing age.3

During the course of primary varicella infection, the herpes virus spreads from infected lesions to the contiguous endings of sensory nerves and travels to the dorsal root ganglion cells where it remains latent.1 It is hypothesized that cell-mediated immunity suppresses viral activity and maintains viral latency. A decline in varicella zoster virus–specific cell-mediated immunity can result in reactivation of the latent virus.1 The virus is then transported to the skin from the dorsal root ganglion via myelinated nerves, which terminate at the isthmus of hair follicles, and subsequent infection of the folliculosebaceous unit occurs.4

Laboratory tests that can assist in the diagnosis of herpes zoster, especially atypical cases, include Tzanck smear and viral culture of the vesicle fluid.1 When vesicles are not present, biopsy of the lesion followed by immunohistochemical staining and polymerase chain reaction assay can aid in the diagnosis. The differential diagnosis for our patient included pseudolymphoma, herpes simplex virus, lymphomatoid papulosis, sarcoidosis, trigeminal trophic syndrome, and Sweet syndrome.

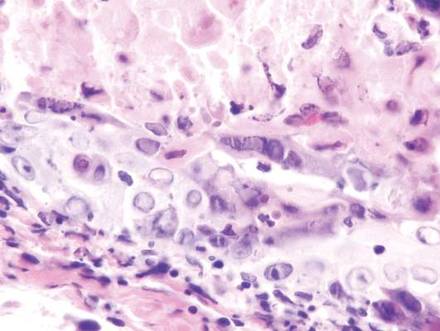

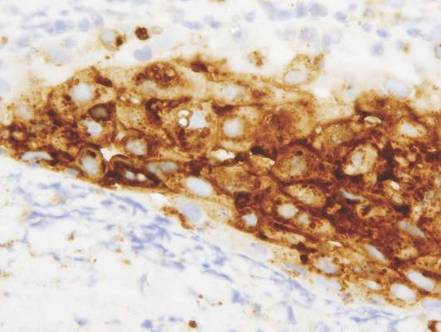

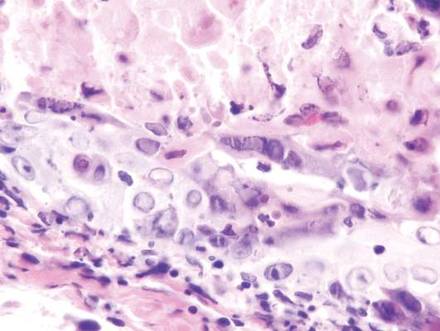

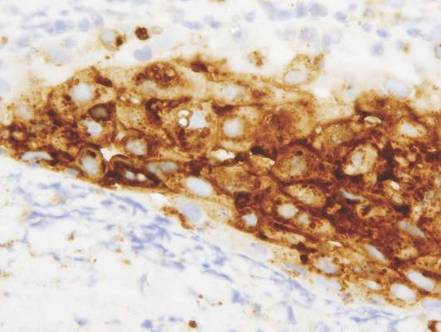

Vesicles were not present in our patient, but the dermatomal nature of the eruption and the pain she experienced made the clinical scenario suspicious for herpes zoster. A 4-mm punch biopsy of a single folliculosebaceous unit revealed herpetic, cytopathic features including prominent keratinocyte necrosis involving sebaceous, isthmic, and infundibular epithelium; ballooning of epithelial cells with steel gray nuclei; and multinucleation with nuclear molding (Figure 1). Strong nuclear and cytoplasmic staining was seen in the affected keratinocytes under anti–varicella zoster virus immunohistochemical analysis (Figure 2). Staining for herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2 was negative. Within days of starting valacyclovir 1000 mg (every 8 hours for 1 week), the patient’s symptoms resolved.

|  | |

|

|

Atypical presentations of herpes zoster (eg, presentations that are not completely dermatomal) are becoming more common. Herpetic infections should always be in the differential diagnosis for cutaneous ulcerations. Misdiagnosis of herpes zoster due to atypical features is common and can delay prompt and adequate treatment.

- Rockley PF, Tyring SK. Pathophysiology and clinical manifestations of varicella zoster virus infections. Int J Dermatol. 1994;33:227-232.

- Chen TM, George S, Woodruff CA, et al. Clinical manifestations of varicella-zoster virus infection. Dermatol Clin. 2002;20:267-282.

- Hope-Simpson RE. The nature of herpes zoster: a long-term study and a new hypothesis. Proc R Soc Med. 1965;58:9-20.

- Walsh N, Boutilier R, Glasgow D, et al. Exclusive involvement of folliculosebaceous units by herpes: a reflection of early herpes zoster. Am J Dermatopathol. 2005;27:189-194.

The Diagnosis: Herpes Zoster

Herpes zoster is a common infection that clinically presents with moderate to intense pain in the involved dermatome (1–3 days before the outbreak1) followed by a unilateral dermatomal eruption. The most common sites of involvement include the trunk (dermatomes T3–L2) and upper face (dermatome V1).2 Herpes zoster characteristically begins as erythematous macules and papules that progress to vesicles and sometimes pustules, which subsequently crust over (7–10 days after the initial outbreak).1 Regional lymphadenopathy is present in most cases. Due to the classic presentation of herpes zoster, clinical diagnosis is the mainstay for most cases. Although it can present in any age group, herpes zoster is most commonly associated with advancing age.3

During the course of primary varicella infection, the herpes virus spreads from infected lesions to the contiguous endings of sensory nerves and travels to the dorsal root ganglion cells where it remains latent.1 It is hypothesized that cell-mediated immunity suppresses viral activity and maintains viral latency. A decline in varicella zoster virus–specific cell-mediated immunity can result in reactivation of the latent virus.1 The virus is then transported to the skin from the dorsal root ganglion via myelinated nerves, which terminate at the isthmus of hair follicles, and subsequent infection of the folliculosebaceous unit occurs.4

Laboratory tests that can assist in the diagnosis of herpes zoster, especially atypical cases, include Tzanck smear and viral culture of the vesicle fluid.1 When vesicles are not present, biopsy of the lesion followed by immunohistochemical staining and polymerase chain reaction assay can aid in the diagnosis. The differential diagnosis for our patient included pseudolymphoma, herpes simplex virus, lymphomatoid papulosis, sarcoidosis, trigeminal trophic syndrome, and Sweet syndrome.

Vesicles were not present in our patient, but the dermatomal nature of the eruption and the pain she experienced made the clinical scenario suspicious for herpes zoster. A 4-mm punch biopsy of a single folliculosebaceous unit revealed herpetic, cytopathic features including prominent keratinocyte necrosis involving sebaceous, isthmic, and infundibular epithelium; ballooning of epithelial cells with steel gray nuclei; and multinucleation with nuclear molding (Figure 1). Strong nuclear and cytoplasmic staining was seen in the affected keratinocytes under anti–varicella zoster virus immunohistochemical analysis (Figure 2). Staining for herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2 was negative. Within days of starting valacyclovir 1000 mg (every 8 hours for 1 week), the patient’s symptoms resolved.

|  | |

|

|

Atypical presentations of herpes zoster (eg, presentations that are not completely dermatomal) are becoming more common. Herpetic infections should always be in the differential diagnosis for cutaneous ulcerations. Misdiagnosis of herpes zoster due to atypical features is common and can delay prompt and adequate treatment.

The Diagnosis: Herpes Zoster

Herpes zoster is a common infection that clinically presents with moderate to intense pain in the involved dermatome (1–3 days before the outbreak1) followed by a unilateral dermatomal eruption. The most common sites of involvement include the trunk (dermatomes T3–L2) and upper face (dermatome V1).2 Herpes zoster characteristically begins as erythematous macules and papules that progress to vesicles and sometimes pustules, which subsequently crust over (7–10 days after the initial outbreak).1 Regional lymphadenopathy is present in most cases. Due to the classic presentation of herpes zoster, clinical diagnosis is the mainstay for most cases. Although it can present in any age group, herpes zoster is most commonly associated with advancing age.3

During the course of primary varicella infection, the herpes virus spreads from infected lesions to the contiguous endings of sensory nerves and travels to the dorsal root ganglion cells where it remains latent.1 It is hypothesized that cell-mediated immunity suppresses viral activity and maintains viral latency. A decline in varicella zoster virus–specific cell-mediated immunity can result in reactivation of the latent virus.1 The virus is then transported to the skin from the dorsal root ganglion via myelinated nerves, which terminate at the isthmus of hair follicles, and subsequent infection of the folliculosebaceous unit occurs.4

Laboratory tests that can assist in the diagnosis of herpes zoster, especially atypical cases, include Tzanck smear and viral culture of the vesicle fluid.1 When vesicles are not present, biopsy of the lesion followed by immunohistochemical staining and polymerase chain reaction assay can aid in the diagnosis. The differential diagnosis for our patient included pseudolymphoma, herpes simplex virus, lymphomatoid papulosis, sarcoidosis, trigeminal trophic syndrome, and Sweet syndrome.

Vesicles were not present in our patient, but the dermatomal nature of the eruption and the pain she experienced made the clinical scenario suspicious for herpes zoster. A 4-mm punch biopsy of a single folliculosebaceous unit revealed herpetic, cytopathic features including prominent keratinocyte necrosis involving sebaceous, isthmic, and infundibular epithelium; ballooning of epithelial cells with steel gray nuclei; and multinucleation with nuclear molding (Figure 1). Strong nuclear and cytoplasmic staining was seen in the affected keratinocytes under anti–varicella zoster virus immunohistochemical analysis (Figure 2). Staining for herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2 was negative. Within days of starting valacyclovir 1000 mg (every 8 hours for 1 week), the patient’s symptoms resolved.

|  | |

|

|

Atypical presentations of herpes zoster (eg, presentations that are not completely dermatomal) are becoming more common. Herpetic infections should always be in the differential diagnosis for cutaneous ulcerations. Misdiagnosis of herpes zoster due to atypical features is common and can delay prompt and adequate treatment.

- Rockley PF, Tyring SK. Pathophysiology and clinical manifestations of varicella zoster virus infections. Int J Dermatol. 1994;33:227-232.

- Chen TM, George S, Woodruff CA, et al. Clinical manifestations of varicella-zoster virus infection. Dermatol Clin. 2002;20:267-282.

- Hope-Simpson RE. The nature of herpes zoster: a long-term study and a new hypothesis. Proc R Soc Med. 1965;58:9-20.

- Walsh N, Boutilier R, Glasgow D, et al. Exclusive involvement of folliculosebaceous units by herpes: a reflection of early herpes zoster. Am J Dermatopathol. 2005;27:189-194.

- Rockley PF, Tyring SK. Pathophysiology and clinical manifestations of varicella zoster virus infections. Int J Dermatol. 1994;33:227-232.

- Chen TM, George S, Woodruff CA, et al. Clinical manifestations of varicella-zoster virus infection. Dermatol Clin. 2002;20:267-282.

- Hope-Simpson RE. The nature of herpes zoster: a long-term study and a new hypothesis. Proc R Soc Med. 1965;58:9-20.

- Walsh N, Boutilier R, Glasgow D, et al. Exclusive involvement of folliculosebaceous units by herpes: a reflection of early herpes zoster. Am J Dermatopathol. 2005;27:189-194.

A 32-year-old woman with no remarkable medical history presented with a progressively worsening erythematous and edematous plaque on the right cheek of 8 days’ duration. She had previously been treated by her primary care physician with cephalexin for 3 days and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole for 2 days, which resulted in “flattening” of the plaque, but the lesion did not resolve. She was referred to our dermatology clinic for further evaluation. She denied any trauma to the cheek or scratching of the lesion. On physical examination, a 2-cm pink, erythematous, edematous plaque with a central eschar was noted on the right cheek with crusting of the right nasal wall.