Comment

As denoted by its hyphenated name, VZV infection can cause 2 distinct disease processes.1,2 Varicella, the generalized initial exanthem known as chickenpox, appears predominantly in childhood. With resolution of this primary infection, the virus lies dormant in sensory ganglia, persisting in neurons. Stress, advanced age, and/or compromised immunity may reactivate latent VZV. This secondary expression is known as herpes zoster (shingles), a unilateral eruption of lesions localized to a single dermatome.

In most cases, morphology of the varicella eruption confirms the diagnosis. Lesions evolve through stages from macules and papules to vesicles and pustules and then to crusts. This evolution typically takes 24 to 48 hours.2 The varicella eruption contains an admixture of elements from each stage simultaneously. Crusts usually resolve over an average of 14 days. Serologically, IgM is measurable as early as 1 to 2 days after appearance of the eruption.3,4 Next to appear are IgG antibodies, which generally remain detectable for life. With more than 90% of the US population being seropositive for VZV,5 diagnosis and management of varicella and herpes zoster usually are straightforward; however, there have been unusual variations on this classic sequence of pathogenesis.

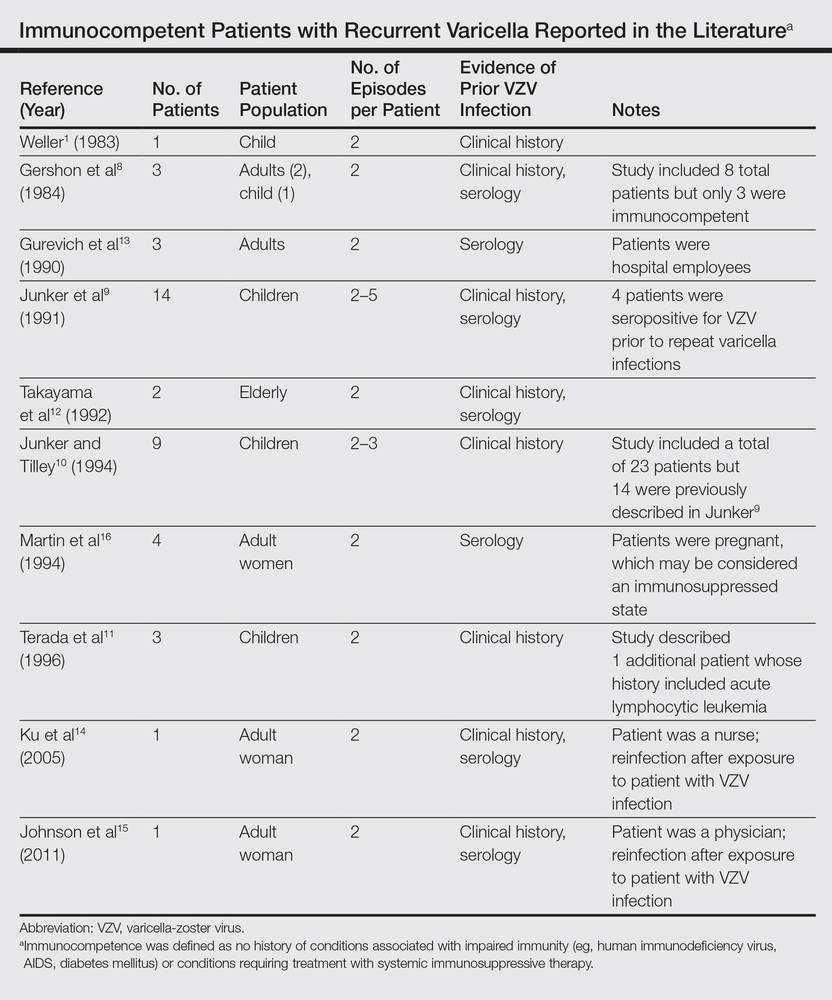

In disseminated zoster, the clinical presentation includes more than 20 lesions outside the dermatome primarily affected.6 Another permutation of VZV infection is zoster sine herpete, which causes the characteristic dermatomal pain of herpes zoster but without the rash.7 Occasionally, 2 cases of chickenpox occur in the same person, usually indicating an underlying immune deficiency. Recurrent varicella in those with intact immunity is purportedly rare. A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the search terms recurrent varicella, chickenpox reinfection, and immunocompetent revealed 41 cases of recurrent varicella in immunocompetent patients in the English language literature occurring among children,1,8-11 adults,8 the elderly,12 health care workers,13-15 and pregnant women16 (Table).

Surveillance studies, however, have challenged the apparent rarity of recurrent varicella, asserting that varicella may recur more frequently than is generally recognized.17,18 Hall et al17 described 9947 cases of varicella, with nearly 6.9% reporting prior varicella infection. Another surveillance report by Marin et al18 evaluating data from 1047 adults with varicella noted that 21% of participants reported prior VZV infections. Both of these studies defined varicella by clinical parameters as a condition with acute onset of generalized maculopapulovesicular rash without other known cause. Although laboratory confirmation of VZV infection was not documented in either study, a history of varicella is considered a reliable indicator of immunity. In fact, studies show that a history of varicella is associated with serologic evidence of immunity 97% to 100% of the time.19,20

Immunity against VZV in humans is not well understood. Although both humoral and cellular factors play a role, cell-mediated immunity may be more important in suppressing primary infection and defending against reinfection. Varicella is more likely to disseminate in lymphopenic patients,21,22 while its course is uninfluenced by hypogammaglobulinemia.1,23 One study of simian varicella virus, which demonstrates 75% genetic homology with VZV, noted that simian varicella virus–infected rhesus macaques without CD4+ T lymphocyte response experienced higher viral loads, prolonged viremia, and disseminated varicella.24 The loss of CD20+ B lymphocytes did not intensify the severity of varicella in the primate model. It is accepted, however, that waning humoral immunity and lower antibody levels correlate with varicella recurrence.25 Ethnicity may impact immunoglobulin persistence. One investigation postulated that individuals with darker skin types experience reduced viral shedding and therefore less antigenic boosting from secondary VZV infections, as they may less readily maintain protective levels of VZV-specific immunoglobulins.25 This phenomenon may have contributed to the 3 episodes of varicella in our patient.

Virulence factors that are intrinsic to VZV may also prompt reinfection. Although taxonomy is still in flux, 3 to 5 major genotypes of VZV have been recognized to date, categorized into European (Dumas), Japanese (Oka), and mosaic clades.26-28 In one study population, approximately 80% of the VZV strains isolated in the United States were of the European variety.26 It is unclear whether infection with one strain of VZV affords immunoprotection against the other strains. Interestingly, one report documented recurrent herpes zoster caused by 2 distinct VZV strains in the same individual.29 Since subtypes of VZV vary geographically, it is possible that increasing global travel may correlate with increased incidence and reporting of varicella reinfection, particularly in cosmopolitan centers. In patients with recurrent varicella, a careful investigation of their international travel history may be necessary.