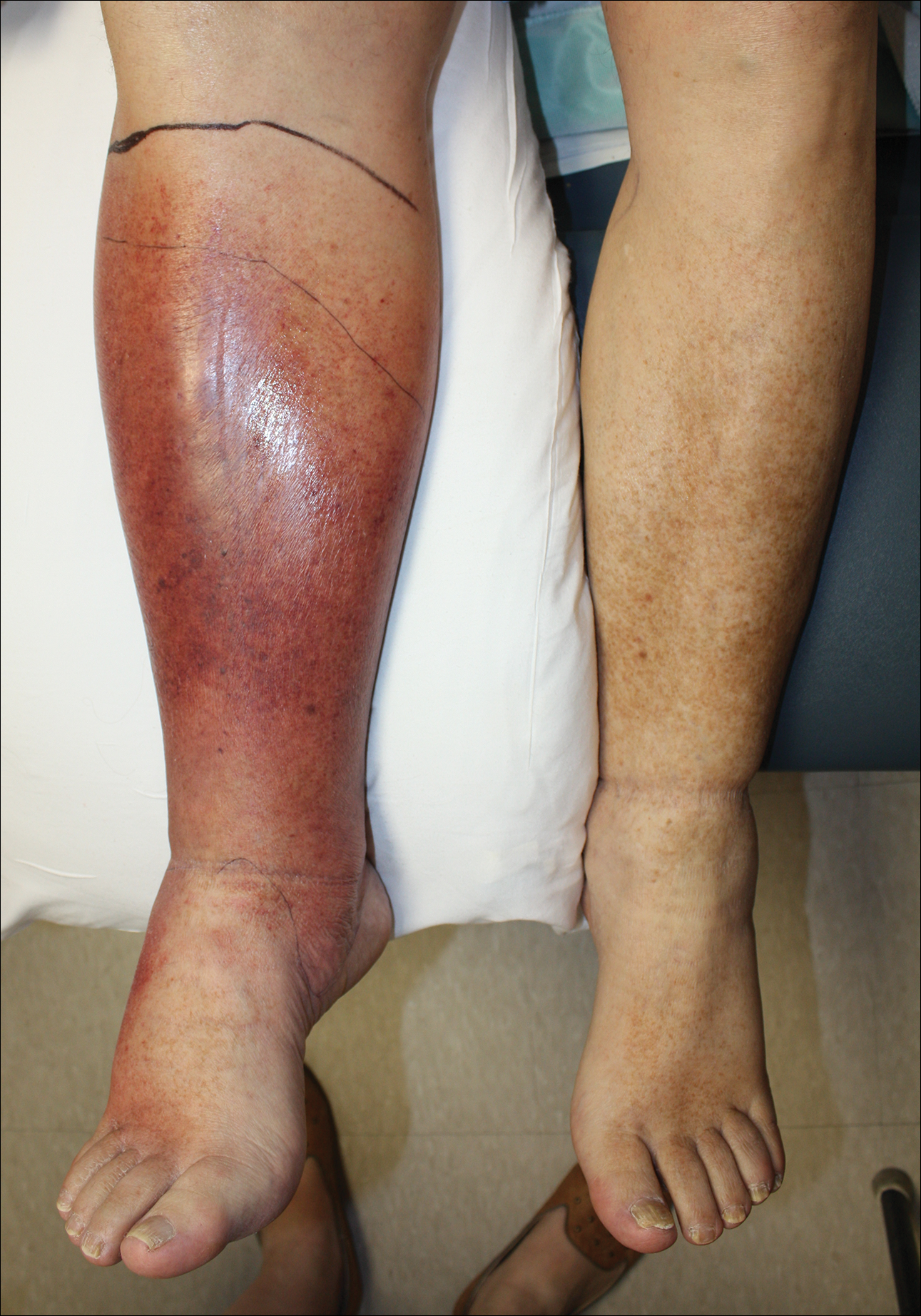

Cellulitis is defined as an acute or subacute, bacterial-induced inflammation of subcutaneous tissue that can extend superficially. The inciting incident often is assumed to be invasion of bacteria through loose connective tissue.1 Although cellulitis is bacterial in origin, it often is difficult to culture the offending microorganism from biopsy sites, swabs, or blood. Erythema, fever, induration, and tenderness are largely seen as clinical manifestations. Moderate and severe cases may be accompanied by fever, malaise, and leukocytosis. The lower extremity is the most common location of involvement (Figure 1), and usually a wound, ulcer, or interdigital superficial infection can be identified and implicated as the source of entry.

Effective treatment of cellulitis is necessary because complications such as abscesses, underlying fascia or muscle involvement, and septicemia can develop, leading to poor outcomes. Antibiotics should be administered intravenously in patients with suspected fascial involvement, septicemia, or dermal necrosis, or in those with an immunological comorbidity.2

The differential diagnosis of lower extremity cellulitis is wide due to the existence of several mimicking dermatologic conditions. These so-called pseudocellulitis conditions include stasis dermatitis, venous ulceration, acute lipodermatosclerosis, pigmented purpura, vasculopathy, contact dermatitis, adverse medication reaction, and arthropod bite. Stasis dermatitis and lipodermatosclerosis, both arising from venous insufficiency, are by far 2 of the most common skin conditions that imitate cellulitis.

Stasis dermatitis is a common condition in the United States and Europe, usually manifesting as a pigmented purpuric dermatosis on anterior tibial surfaces, around the ankle, or overlying dependent varicosities. Skin changes can include hyperpigmentation, edema, mild scaling, eczematous patches, and even ulceration.3

Lipodermatosclerosis is a disorder of progressive fibrosis of subcutaneous fat. It is more common in middle-aged women who have a high body mass index and a venous abnormality.4 This form of panniculitis typically affects the lower extremities bilaterally, manifesting as erythematous and indurated skin changes, sometimes described as inverted champagne bottles (Figure 2). At times, there can be accompanying painful ulceration on the erythematous areas, features that closely resemble cellulitis.5,6 Lipodermatosclerosis is commonly misdiagnosed as cellulitis, leading to inappropriate prescription of antibiotics.7

Distinguishing cellulitis from noncellulitic conditions of the lower extremity is paramount to effective patient management in the emergent setting. With a reported incidence of 24.6 per 100 person-years, cellulitis constitutes 1% to 14% of emergency department visits and 4% to 7% of hospital admissions.Therefore, prompt appropriate diagnosis and treatment can avoid life-threatening complications associated with infection such as sepsis, abscess, lymphangitis, and necrotizing fasciitis.8-11

It is estimated that 10% to 20% of patients who have been given a diagnosis of cellulitis do not actually have the disease.2,12 This discrepancy consumes a remarkable amount of hospital resources and can lead to inappropriate or excessive use of antibiotics.13 Although the true incidence of adverse antibiotic reactions is unknown, it is estimated that they are the cause of 3% to 6% of acute hospital admissions and occur in 10% to 15% of inpatients admitted for other primary reasons.14 These findings illustrate the potential for an increased risk for morbidity and increased length of stay for patients beginning an antibiotic regimen, especially when the agents are administered unnecessarily. In addition, inappropriate antibiotic use contributes to antibiotic resistance, which continues to be a major problem, especially in hospitalized patients.

There is a lack of consensus in the literature about methods to risk stratify patients who present with acute dermatologic conditions that include and resemble cellulitis. We sought to identify clinical features based on available clinical literature-derived variables. We tested our scheme in a series of patients with a known diagnosis of cellulitis or other dermatologic pathology of the lower extremity to assess the validity of the following 7 clinical criteria: acute onset, erythema, pyrexia, history of associated trauma, tenderness, unilaterality, and leukocytosis.