Molluscum contagiosum virus (MCV) is a common pediatric viral infection of the skin and/or mucous membranes.1 It has been noted in increasingly younger patient populations, ranging from congenital cases resulting from perinatal/vertical transmission to transmission from cobathing and pool usage.2,3Adolescent cases of MCV infection presumed to be sexually transmitted also have been reported.1

An association between MCV infection and atopic dermatitis (AD) has been reported to be caused by a predisposition to prolonged and severe cutaneous viral infections.4 However, the exact nature of the relationship between MCV and AD is unknown. It is not clear if there is a greater incidence of MCV infection in AD patients, a greater number of MCV lesions when MCV infection and AD co-occur,5 or just more associated dermatitis in the setting of the combination of AD and MCV.6

The purpose of this study was to identify pediatric patients with AD onset or flare of AD triggered by MCV infection as well as to characterize the setting under which MCV may trigger AD onset or flares in children.

Methods

Medical records for 50 children with prior or current MCV infection who presented sequentially to an outpatient pediatric dermatology practice over a 1-month period were identified. Institutional review board approval was obtained. Patients were categorized according to the following parameters, which were identified as available data entry points: age at examination (last available); age at onset of MCV infection; duration of MCV infection (months); history of cobathing and with whom as well as presence of MCV infection in the cobather; usage of pools just prior to onset of MCV infection; enrollment in daycare just prior to onset of MCV infection; family and/or personal history of AD and/or psoriasis; presence of AD prior to onset of MCV infection; persistence of AD after clearance of MCV (yes/no); duration of AD following resolution of MCV infection; location of AD; location of MCV infection; number of MCV lesions documented; presence of unusual MCV morphology; therapeutics received; and comorbidities. Statistics were run using spreadsheet software.

Results

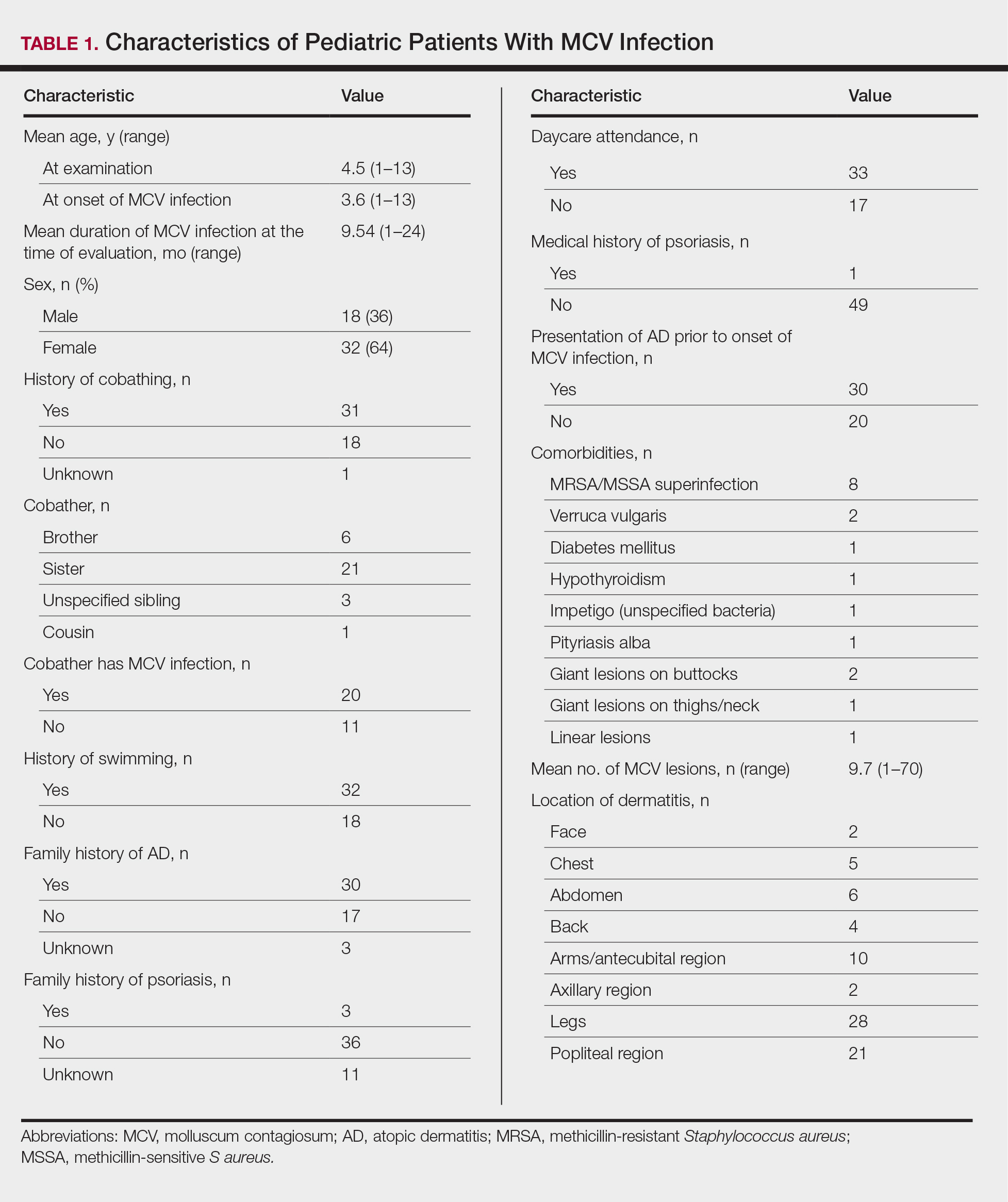

The age range of the 50 patients with MCV infection was 1 to 13 years, with an average age of 3.6 years at the onset of infection (reported by parents/guardians) and 4.5 years at presentation to the pediatric dermatology office (Table 1). Children 3 years of age or younger were more likely to have MCV lesions below the waist (P<.05). The majority of patients were female, but AD onset or flares triggered by MCV infection were not associated with sex.

The role of cobathing is unknown; however, 62% (31/50) of patients previously or currently cobathed at home, suggesting it may be a risk factor for MCV infection. An association of MCV lesions in the popliteal region trended toward being more likely with cobathing, but the association was not statistically significant.

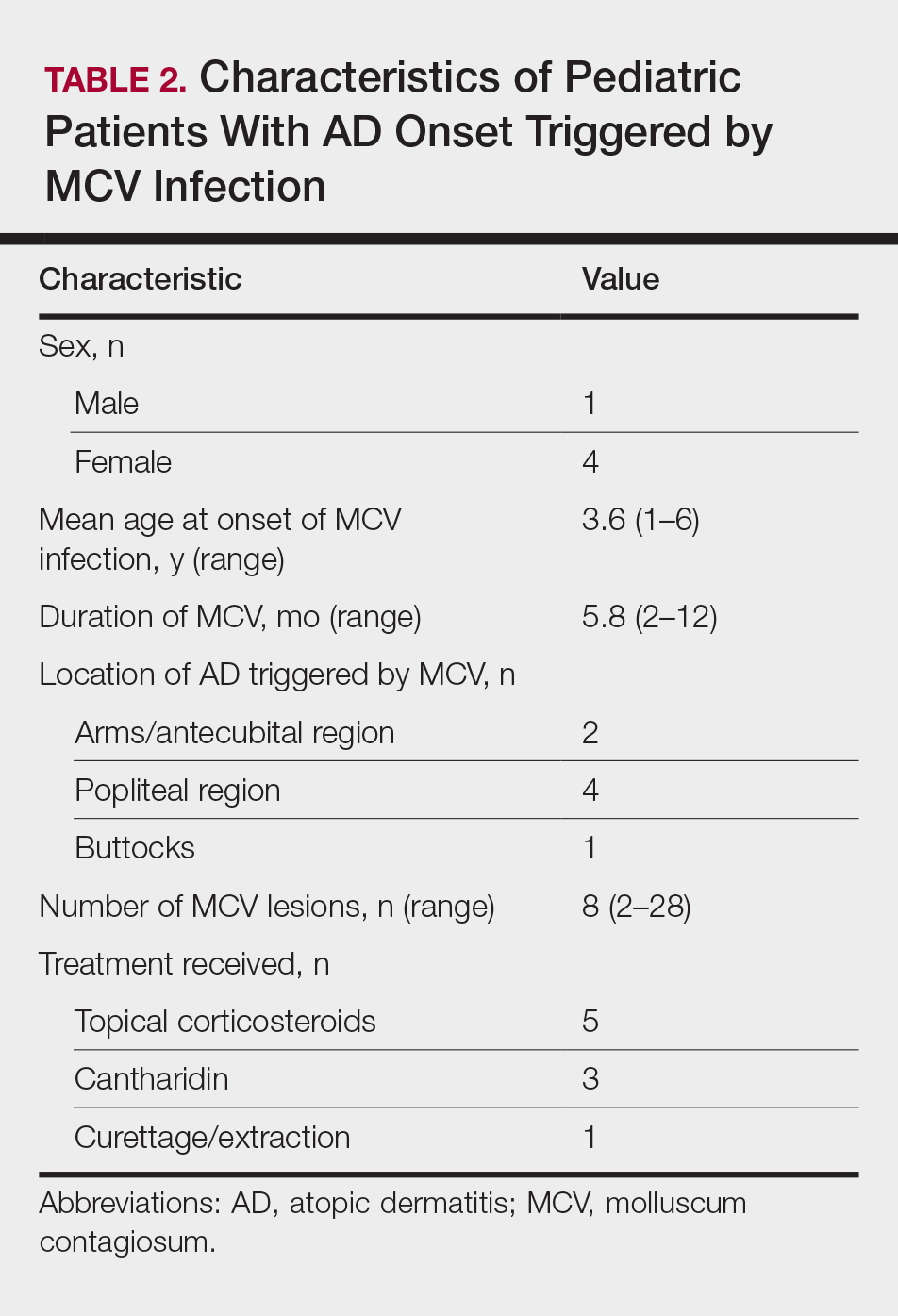

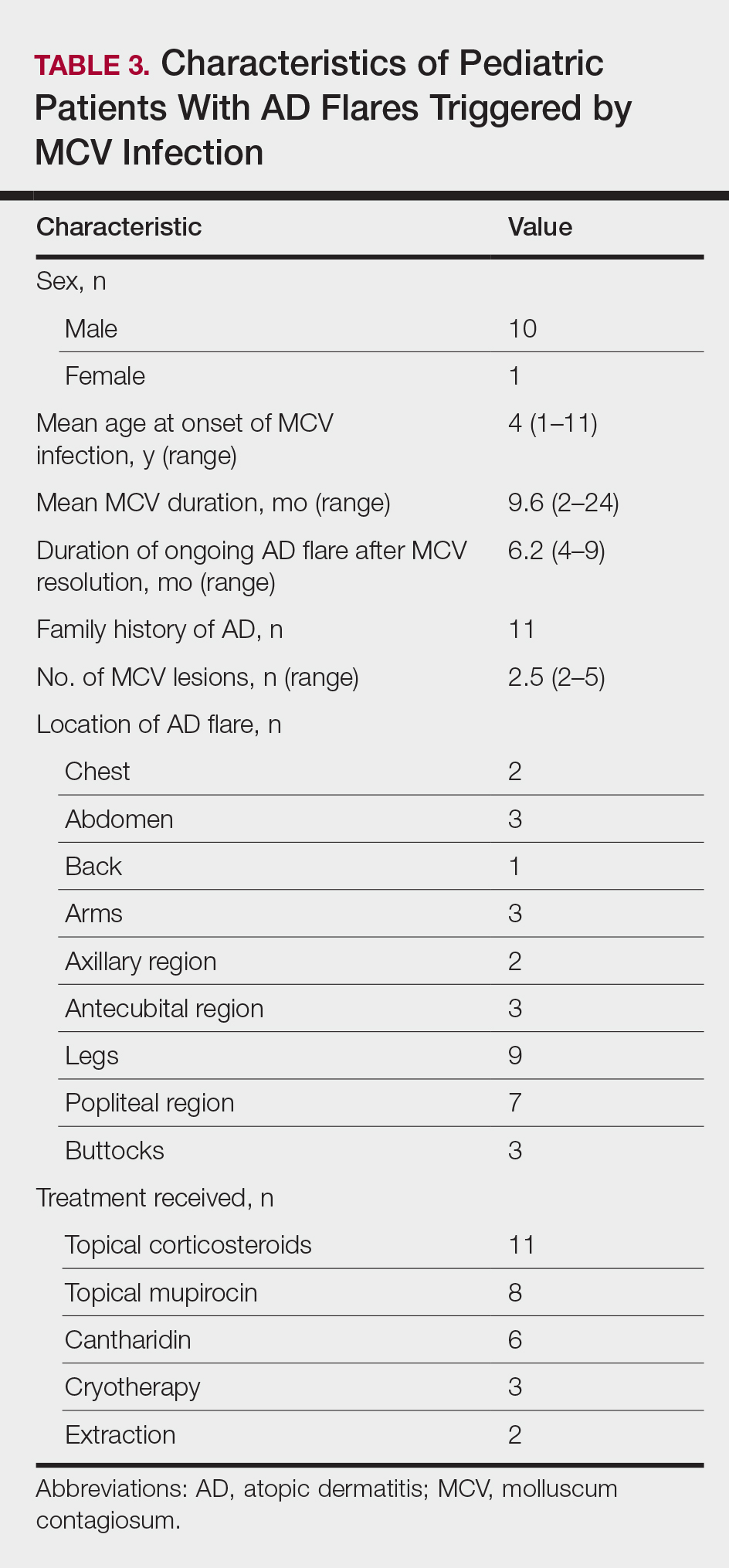

Children with AD onset triggered by MCV infection statistically were more likely to have flexural localization of MCV and AD lesions and were statistically more likely to have a family history of AD (P<.04)(Table 2). Children with AD flares triggered by MCV infection were more likely to have MCV and AD lesions of the popliteal region and legs (P<.05)(Figure) and family history of AD (P<.04)(Table 3). Location of MCV lesions on the upper and lower extremities, buttocks, and genitalia were more likely to be associated with presence of any dermatitis than facial and/or truncal lesions (P<.05). Treatment of the MCV infection did not appear to impact the course of AD when present, but prospective interventions would be needed to assess this issue.

Superinfection with methicillin-resistant and methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus as well as atypical giant lesions of the intertriginous neck, inner thighs, and buttocks also were noted, but AD was uncommon in these cases. Given the limited number of cases, statistical significance could not be assessed.

Comment

Cutaneous infections with Malassezia have been postulated to trigger AD in infancy,1 while systemic viral infections such as varicella-zoster virus may be protective against AD when acquired in younger children.7 It appears that MCV infection in young children (eg, 3 years or younger) with specific localization to the flexural areas has the potential to trigger AD in susceptible hosts. Larger studies are needed to chart the long-term disease course of AD in these children. Due to the small size of this study, it is unclear if the rise of MCV infections since the 1980s has contributed to increased AD.8 Susceptible children appear to have a family history of AD and localization of MCV lesions on the legs, buttocks, and antecubital region. Atopic dermatitis risk appears to be highest when MCV lesions are localized to intertriginous or flexural locations.

In addition to triggering the onset of AD, MCV infection also can trigger persistent flaring of AD, especially in the popliteal region and legs. Atopic dermatitis flares can occur at any age, but they appear to cluster in preschoolers and typically are not prevented by AD or MCV treatments; however, randomized trials are needed to identify if early intervention of MCV has a preventive benefit on AD onset or flares, and longer-term observation is needed to identify true disease course modification. Reduction of the number of MCV lesions previously has been demonstrated with institution of topical corticosteroid therapy.6 Therefore, institution of atopic skin care generally is advisable in the setting of MCV infection. Future studies should address the potential use of interventions to prevent the triggering of AD onset or flares in the setting of MCV infection in children.5