To the Editor:

It is not uncommon for patients with extensive dermal scarring to overheat due to the inability to regulate body temperature through evaporative heat loss, as lack of perspiration in areas of prior full-thickness skin injury is well known. One of the authors (C.M.H.) previously reported a case of a patient with considerable hypertrophic scarring after surviving an episode of toxic epidermal necrolysis that was likely precipitated by lamotrigine.1 The patient initially presented to our clinic in consultation for laser therapy to improve the pliability and cosmetic appearance of the scars; however, approximately 3 weeks after initiating treatment with a fractional CO2 laser, the patient noticed perspiration in areas where she once lacked the ability to perspire as well as improved functionality.1 It was speculated that scar remodeling stimulated by the CO2 fractional laser allowed new connections to form between eccrine ducts in the dermis and epidermis.2

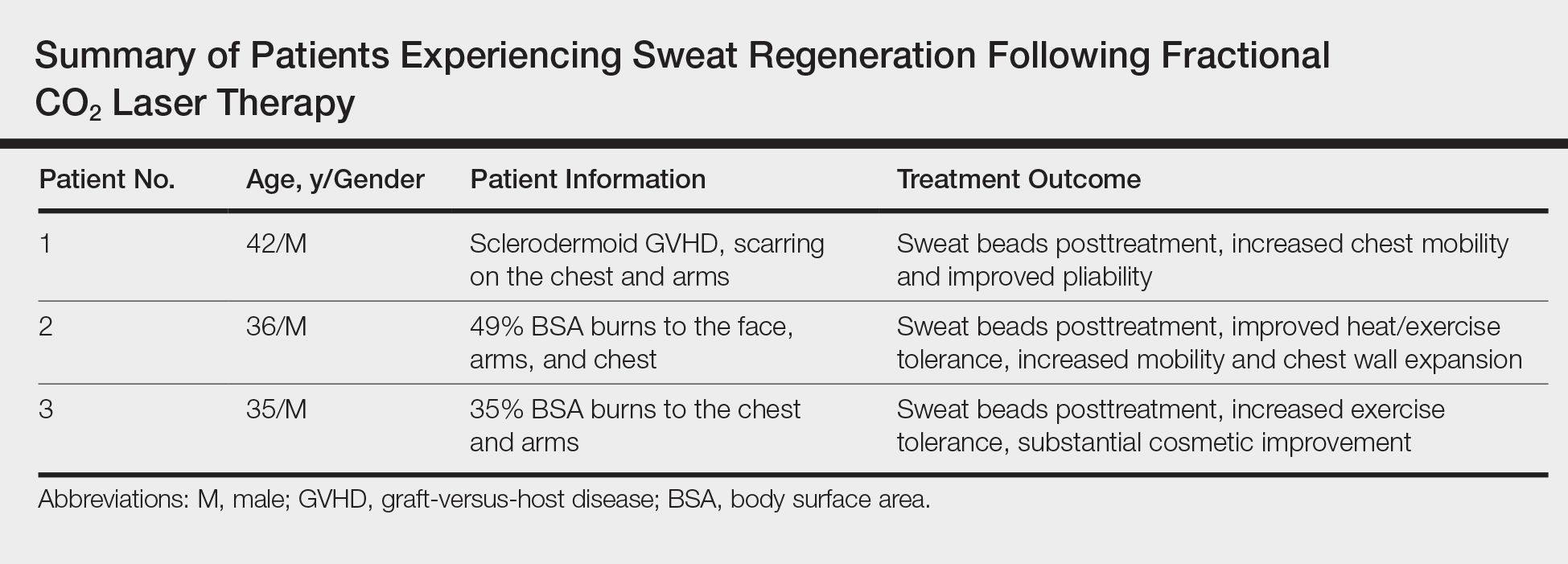

These findings are even more notable in light of a study by Rittié et al3 that suggested the primary appendages of the skin involved in human wound healing are the eccrine sweat glands. The investigators were able to demonstrate that eccrine sweat glands are major contributors in reepithelialization and wound healing in humans; therefore, it is possible that stimulating these glands with the CO2 laser may promote enhanced reepithelialization in addition to the reestablishment of perspiration and wound healing.3 Considering inadequate wound repair represents a substantial disturbance to the patient and health care system, this finding offers promise as a potential means to decrease morbidity in patients with dermal scarring from burns and traumatic injuries. We have since evaluated and treated 3 patients who demonstrated sweat regeneration following treatment with the fractional CO2 laser (Table).

A 42-year-old man was our first patient to demonstrate functional scar improvement following bone marrow transplant for acute lymphoblastic leukemia complicated by chronic sclerodermoid graft-versus-host disease and subsequent extensive scarring on the chest and arms. Approximately 2 weeks after the first treatment with the fractional CO2 laser, the patient began to notice the presence of sweat beads in the treated areas. In addition to the reestablishment of perspiration, the patient had perceived increased mobility with improved pliability and “softness” (as described by family members) in treated areas likely related to scar remodeling.

A 36-year-old wounded army veteran presented with burns to the face, arms, and chest affecting 49% of the body surface area. After only 1 treatment, the patient reported that he could subjectively tolerate 10°F more ambient temperature and work all day outside in south Texas when heat intolerance previously would allow him to work only 2 to 3 hours. Additionally, he noted increased mobility and chest wall expansion, which in combination contributed to overall increased exercise tolerance and enhanced quality of life.

A 35-year-old US Marine and firefighter with burns primarily on the chest and arms involving 35% body surface area experienced increased exercise tolerance and sweat regeneration, particularly on the chest after a single treatment with the fractional CO2 laser but continued to experience improvement after a total of 3 treatments. Additionally, the cosmetic improvement was so substantial that the physician (C.M.H) had to review older photographs to verify the location of the scars.

We have now treated 3 patients with various mechanisms of injury and extensive scarring who noticed improved heat tolerance from sweat regeneration following fractional CO2 laser therapy. At this point, we only have anecdotal evidence of subjective functional improvement, and further research is warranted to elucidate the exact mechanism of action to support our findings.