Acute hemorrhagic edema of infancy (AHEI) is an uncommon leukocytoclastic vasculitis affecting children aged 6 to 24 months; Henoch-Schönlein purpura (HSP) is the most common misdiagnosis. The 2 entities should be differentiated, as HSP may have renal and gastrointestinal (GI) comorbidities that need serial follow-up, whereas AHEI follows a benign course without systemic sequelae. Patient history and physical examination are the most important factors in differentiating the 2 diseases; histopathologic and direct immunofluorescence (DIF) analyses may lend further diagnostic confidence.

We report the case of a 10-month-old previously healthy boy who presented with acute rash, edema, and low-grade fever in the setting of recent diarrhea. We differentiate between AHEI and HSP to help prevent misdiagnosis by health care providers.

Case Report

A 10-month-old previously healthy boy presented to the emergency department (ED) for evaluation of a rash and swelling of 4 days’ duration. He had nonbloody diarrhea 1 week prior; soon after, he developed bilateral lower leg edema and rash. On evaluation in a different ED, he had a low-grade fever (rectal temperature, 38.0°C) but normal blood work, including complete blood cell count, basic metabolic panel, and coagulation studies. The patient was discharged to outpatient follow-up with his pediatrician who reported normal urinalysis.

Due to progression of the rash, the patient presented to our ED 3 days after his initial ED assessment. Dermatology was consulted. At the time of presentation, he was afebrile but with GI upset and fussiness. His parents denied additional symptoms or blood in urine or stool. Physical examination revealed a nontoxic-appearing infant with scattered palpable, annular, purpuric papules coalescing into plaques on both legs and feet (Figure 1), with sparse petechiae noted on the lower abdomen. The cheeks had scattered purpuric papules and plaques bilaterally, a few with a small central crust (Figure 2), and the right superior helix had a faint purpuric macule. The hands had a few pink edematous coalescing papules.

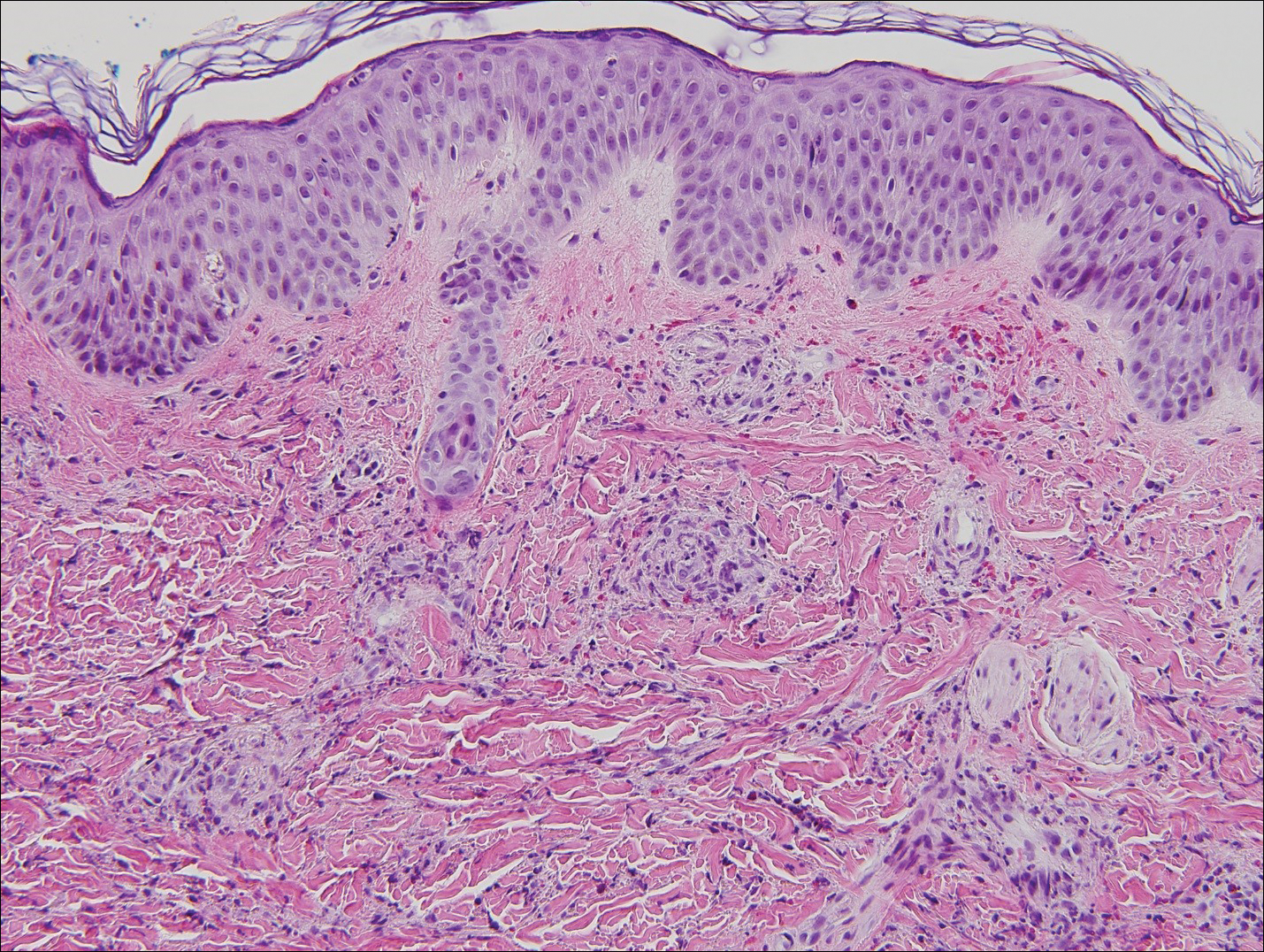

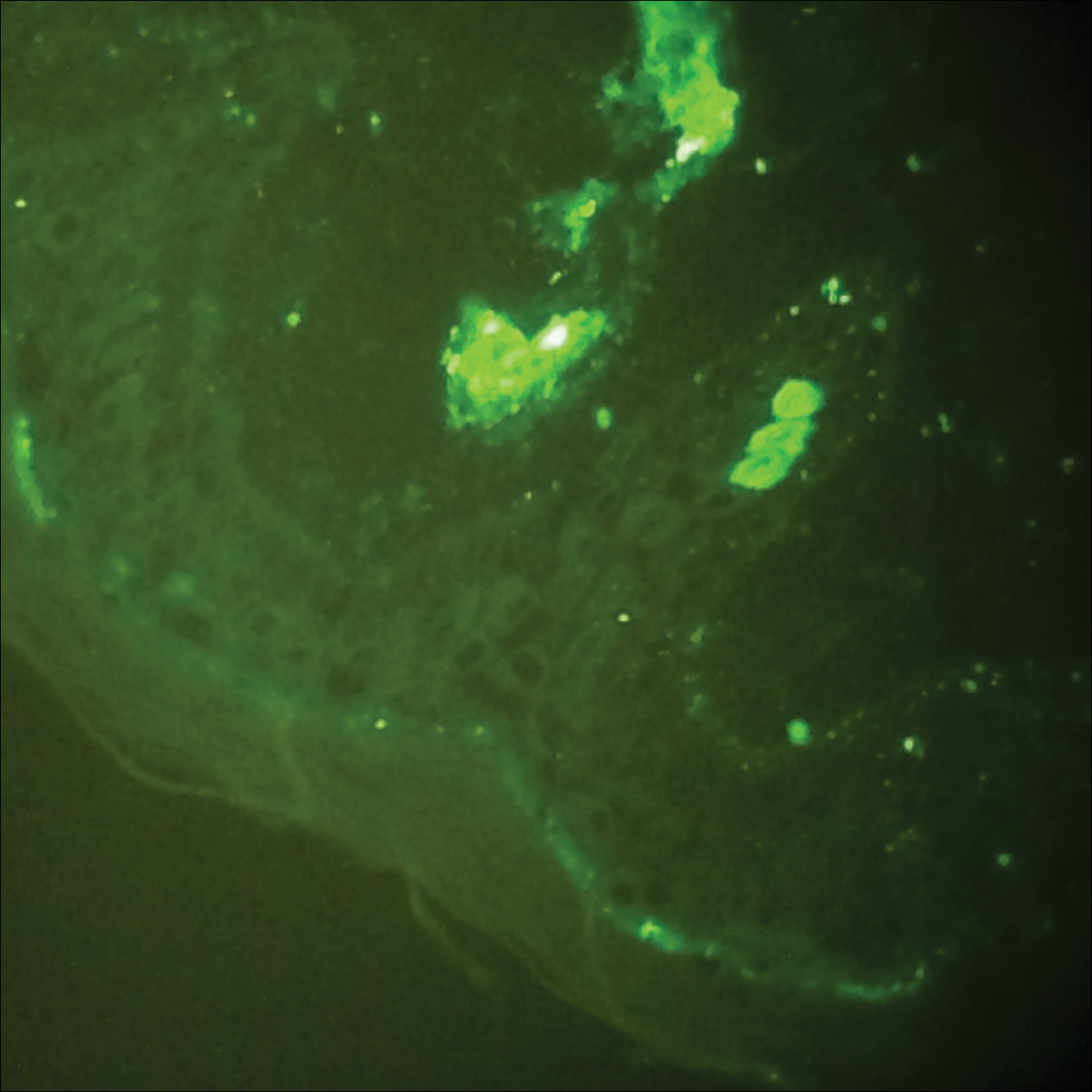

Histopathologic analyses with hematoxylin and eosin staining (Figure 3) and DIF (Figure 4) were performed from within a representative purpuric plaque on the right hip. Direct immunofluorescence was performed to evaluate for an IgA vasculitis versus an alternative type of vasculitis. The hematoxylin and eosin–stained specimen demonstrated a dermal perivascular infiltrate involving superficial and deep vessels with neutrophils, karyorrhexis, and erythrocyte extravasation. The endothelium was intact, with a mild suggestion of fibrinoid change of the blood vessel walls. Direct immunofluorescence revealed granular deposition of IgA, C3, and fibrinogen in multiple dermal blood vessels. Combined, the specimens were interpreted as evolving IgA-associated leukocytoclastic vasculitis.

The case was reviewed with our 2 department pediatric dermatologists; a diagnosis of AHEI was made based on the clinical and supportive histopathological presentations. The patient’s parents chose active treatment with a 2-week taper of oral prednisone because of the patient’s discomfort with edema. No GI or adverse renal sequelae, including findings on urinalysis, were reported at 1-month hospital follow-up with dermatology and pediatrics.